5 The Cognitive Dimension

Theodore Gracyk

Key Takeaways for the Cognitive Dimension

Topic: Do the arts have cognitive value? That is, do the arts teach us anything about the world?

Most accounts of art either stress or assume its cognitive value: exposure to art makes us smarter

Cognitive value is compatible with, and may depend on, formal and aesthetic value

Some art, conceptual art, may have no value other than cognitive value

Despite all of the above, there is long tradition of denying art’s cognitive value

Plato argues that art degrades, rather than improves, understanding of the world around us

Plato argues that aesthetic value and artistic creativity are the chief culprits

Neo-cognitivism defends art’s cognitive value by uncoupling that value from the teaching of facts

Neo-cognitivism requires an account of why imaginative engagement is a cognitive value

Neo-cognitivism looks to non-literal meanings and open-ended implication as the key to art’s cognitive value

5.1 Introduction to Art’s Cognitive Dimension

Tell the truth but tell it slant.

— Emily Dickinson

At least since the time of Aristotle (4th century BCE), art has been identified as valuable for giving us a better understanding of the world. This position is generally known as artistic cognitivism. It is one of the oldest positions debated in philosophy of art, because Aristotle promoted it in response to criticisms of representation made by his teacher, Plato. (See Section 5.2 below.)

According to cognitivism, a painting should do something for the mind. It must do more than simply please the eye. It should increase our knowledge of the world or in some other way enhance our thought processes (cognition). Good music should do more than tickle the ear. In other words, cognitivism says that good art is valuable for the ways in which it improves our understanding of the world or improves our thought processes. Many proponents of expression theory and the aesthetic theory of art end up supplementing those theories by linking them to cognitivism. For example, art that explores human emotion is said to be valuable for giving us a better understanding of human motivation and decision-making.

An obvious challenge to cognitivism is the difficulty in saying how artworks differ from all the other representations that provide information about the world. Consider Alfred Stieglitz’s position that most photography is not art. (See Chapter 1, Section 1.4.) Anyone with a camera — or, today, a mobile phone — can take photographs. Yet we do not think that the millions of photographs taken every day are necessarily art. So, how does art photography differ from all those other photographs? And does art photography improve our understanding of the world more than the photographs that are not classified as art?

Stieglitz proposes that art photography gives us insight into other minds and other perspectives. His explanation of how this happens involves both expression theory and aesthetic formalism, but he supplements them with cognitivism. How so? Although an artwork might have documentary value, Stieglitz proposes that it only becomes art when it goes beyond documentation by communicating the thinking of the artist. So, a photograph becomes art when it provides insight into the the thoughts of someone else.

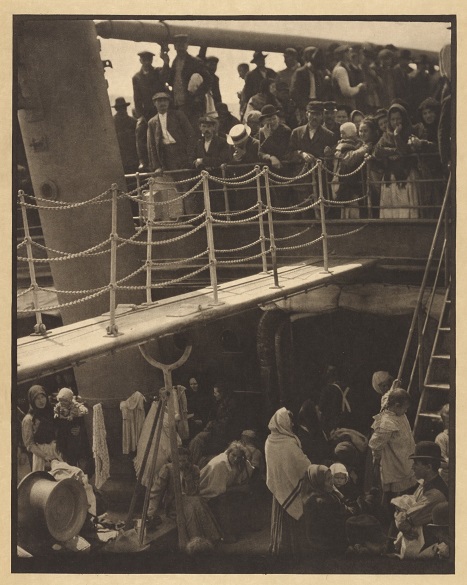

We can see how this is supposed to work by examining one of Stieglitz’s best-known photographs, The Steerage. In 1907, the only way to cross the Atlantic was by ship. Sailing to Europe as a first-class passenger, Stieglitz felt increasing friction with the upper-class, wealthy Americans in first class. He decided to get away by taking a walk around the ocean liner. Unexpectedly, he found himself looking down at the limited area where the poorer steerage-class passengers were allowed to get sun and air. He ran back to his cabin, got his camera, and returned. He exposed the camera’s glass negative when he saw the man in the white straw hat look down, creating a white sphere. Stieglitz was interested in what he saw (poor people, crowded together) and in how it was framed (the mast rising on the left, supporting a spar that created a border across the at the top, and then the bridge cutting the area into upper and lower). Stieglitz later said that if the man in the straw hat had not been there, he would not have taken the picture.

Clearly, then, the goal is not simple documentation. Stieglitz said that his aim was to use a “relationship of shapes” to frame and intensify human drama. The form created by the interaction of mast, spar, and walkway adds framing, energy, and emotional power to the crowd of people. Given the relationship of the camera to the scene, the viewer is literally looking down at the poor. Stieglitz’s formal choices generate expressive power, and together these artistic choices stimulate the viewer to pay attention and study the people in the picture. Formal and expressive values are in the service of cognitive value (i.e., the information in the photograph, together with the photographer’s ability to convey an additional perspective on that information ). The criteria might be summarized as representation that possesses significant form while conveying artistic vision. (See Chapter 4 for the topic of significant form.)

Stieglitz’s explanation of art photography is a classic version of cognitivism. Artists exploit aesthetic properties — formal and expressive properties — in order to guide our attention and stimulate our thinking about a topic.

Nonetheless, skeptics have warned since the dawn of recorded philosophy that art’s cognitive value is seriously over-rated.

Consequently, this chapter contrasts two positions. Section 5.2 presents the skeptical position of anti-cognitivism. It begins with Plato’s argument that even the best artists produce work that has little or no cognitive value.

Section 5.3 offers Immanuel Kant’s defense of artistic cognitivism. (See Chapter 2 for the importance of Kant’s Critique of Judgement of 1790.) Basically, Kant proposes that the best artworks are meaningful symbols. If two artworks possess equivalent aesthetic value, the one that does more to stimulate our thinking has more artistic value than the one that means something trivial. The best art is valuable for its “ineffable” meaning, suggesting things that cannot be stated in a straightforward manner.

Before looking at the specific positions of Plato and Kant, here is additional background on cognitivism, that is, the thesis that good art increases our understanding of the world.

Looking back at Chapter 1 of this book, Charles Batteux qualifies as a cognitivist. Beauty is a defining characteristic of art, but so is the goal of representing the true “nature” (the core essence) of whatever is depicted. Batteux mentions two of Molière’s plays, The Misanthrope (1666) and The Miser (1668). They are entertaining comedies, so French audiences paid to see them. Their entertainment value secures an audience. But the artistic point is to convey what certain kinds of people are like, and why being these approaches to life are undesirable because they have a negative effect on family and community. Each play reveals something about human nature. This element is the play’s cognitive dimension, and cognitivism says that the play’s success in conveying it to audiences is the work’s core artistic value.

However, it is not clear that all art has a lesson to teach the audience. And when that is its main function, it is sometimes dismissed as mere propaganda.

Some cognitivists praise art for exercising the mind (rather than teaching us something specific). If so, art might have a positive effect without the audience being aware that it is changing them. Repeated exposure to Cubist paintings might alter your ideas about spatial organization without your being conscious that this cognitive change has taken place. Repeated exposure to Impressionist paintings might enhance your awareness of the complexity of color and light in your everyday visual experiences. Reading literature stimulates the imagination, exercises memory, improves concentration, and builds vocabulary. And these positive effects on cognitive processes happen even for people who say they don’t like this art. Furthermore, many studies suggest that people who regularly create art as a hobby experience less decline in their cognitive functioning as they age.

Thus, people can obtain cognitive value from art even if they (wrongly) think it only has aesthetic or entertainment value. Again, humor in art is a good example. People say things like, “it’s just a joke,” and “can’t you take a joke?” They mean that what was said should not be taken seriously. But a play such as The Miser isn’t just a joke: it’s a serious commentary on human social relationships. (Generalizing, comedy frequently has a serious point.) So, people can be exposed to serious messages in art without being aware of what’s really happening. Many medications are like this. People who take medications for high blood pressure can’t tell that it’s helping them even when it is. Similarly, many artworks convey a message that is not made explicit. In the same way that a medication might be helping you without your being consciously aware that it is doing so, cognitivism says that art’s primary value is located with the positive change it makes on its audience, not with the experience itself.

So, while many people believe that the main value of an artwork is the pleasure it gives, cognitivism holds that this pleasure is merely a means to get people to attend to it in order to gain cognitive benefits. To put this another way, art is similar to the cherry-flavor added to liquid medication created for children. The child takes the medicine because it tastes good, but the parent gives it to the child because of its medicinal effects. Similarly, the audience attends to art because they enjoy it in some way (its aesthetic effect), but the artist’s true purpose in creating the artwork is to educate the audience in some manner.

An obvious objection to this line of defense is that a lot of art, especially modern art, does not offer immediate enjoyment. For the sake of argument, let us accept that point. In fact, it makes cognitivism attractive as an explanation of why people engage with art that has no immediate aesthetic payoff, since it is difficult to identify any other payoff besides cognitive rewards.

Modernism in art can be characterized as the art movement that brought cognitive value to the forefront, often at the expense of aesthetic value. One of the advantages of cognitivism is that it provides a plausible explanation of the value of the many modern and post-modern artworks that seem to have limited aesthetic merit.

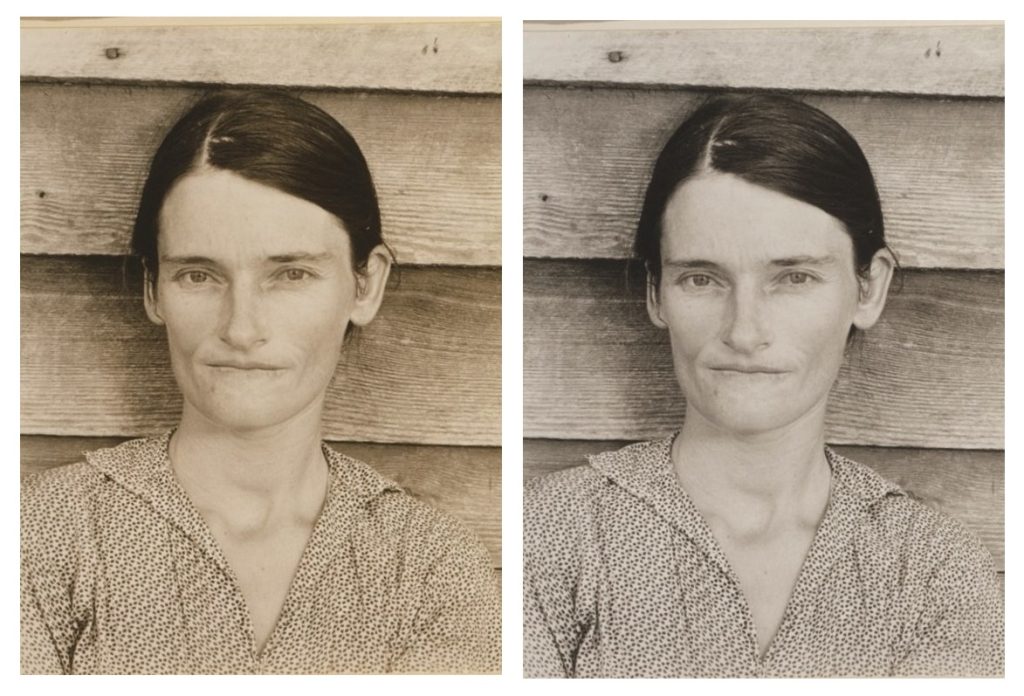

For example, in 1936 Walker Evans photographed individuals and scenes in rural Alabama. A number of these photographs have become well known, both as documents of poverty during the Great Depression and as art objects — he was the first photographer to receive a solo show at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art (in 1938). However, because some of Evans’s most iconic images were works for hire by the Farm Security Administration of the federal government, Evans was not entitled to claim copyright. Instead, the images are in the public domain and anyone can reproduce them. In 1981, a New York art gallery exhibited a show of photographs, Sherrie Levine after Walker Evans. All of the photographs bore that same title, and each was a photo that Levine had made by photographing the images in a book of Walker Evans photographs. (See figure 5.2.) Other than a slight difference in tonal quality, one cannot tell them apart by looking at them. Since any aesthetic value found in Levine’s photographs is already present in the originals, Levine’s pictures cannot be of value to viewers for aesthetic reasons. (Any aesthetic achievement would have to be assigned to Evans, and for that purpose one could simply look at a book of his photographs instead of looking at Levine’s photographs.) And, seemingly, her photographs must also be equivalent in their expressive, that is to say emotional, impact.

If there is no relevant aesthetic or expressive difference, why should anyone engage with Levine’s photograph of Evans’s photograph of Allie Mae Burroughs?

The point has to be that the two photographs make radically different artistic statements. The difference is cognitive. Levine’s photograph means something different from Evans’s original.

Where Evans is calling attention to the suffering of America’s working poor in the 1930s, Levine’s pictures are normally understood to make dual statements. On the one hand, they suggest that, economically, nothing has changed in America. On the other hand, they call attention to the question of what counts as originality in photography, given the medium’s inherent transparency. Finally, some art critics regard her decision to appropriate the images of a highly respected male photographer as central to her message. This art is about making art in a biased artworld.

According to this third line of interpretation, Levine’s act of copying is generally understood to be a feminist, transgressive gesture that calls attention to Levine’s status as a woman artist in the late twentieth century, working in a system that favors male artists. What is the point, the photos seem to ask, of trying to be original when you cannot escape comparison to established artists? Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol had pioneered visual art that highlights appropriation, and their work generally encouraged either puzzlement or amusement. In contrast, Levine’s art incited considerable anger in other (overwhelmingly male) artists. Her apparent lack of originality in making photographs of photographs blinded many viewers to the originality of her moving photography into the realm of conceptual art (i.e., to display photographs that invite a purely cognitive interpretation). Although Levine herself denied having any such intention, they are additionally taken to be statements about women’s access to property in a paternalistic society.

In other words, Levine’s copies are artistically valuable for making us think about the ideas of photography, authorship, ownership, and property, especially in relation to gender. Instead of making some obvious direct statement, the photographs invite us to consider multiple interpretations. In this manner, they communicate indirectly by presenting ineffable content. (This proposal aligns them with Immanuel Kant’s theory of aesthetic ideas as explained below in Section 5.3.)

This does not mean that cognitive value is always associated with challenges to the viewer’s existing mindset. Cognitive value is also present in art that embodies and reinforces a culture’s traditional values. The use of Greek columns on American government buildings — the Lincoln Memorial and the Supreme Court Building in Washington, D.C. — would be an example of this sort of art.

5.2 Plato attacks cognitivism

Despite its plausibility, a cognitive theory of art faces well-known obstacles. Some of the most stinging criticisms were made by Plato. Just as Immanuel Kant is considered the most important philosopher of the modern period, Plato is considered the most important figure of ancient European philosophy. Alfred North Whitehead famously summarized his importance by saying, “All of Western philosophy is but a footnote to Plato.”

Plato is the earliest European philosopher whose writings have come down to us relatively intact. We have only fragments from earlier philosophers, or know about them through second-hand reports (including what Plato said about them). The most famous of his writings is The Republic, a book that is mainly about political theory but which contains lengthy discussions of literature and music. Although Plato did not talk about “art” and did not have any general theory of art, his discussion of visual art and poetry is generally understood to be a foundational document in the philosophy of art. In what follows, keep in mind that the Greek term poiesis (translated here as “poetry”) also included storytelling and theater.

Plato thinks that the cognitive effects of poetry are more negative than positive. He thinks that listening to the narrated poetry of Homer and his stories of Achilles (hero of The Iliad) and Odysseus (hero of The Odyssey) are distractions from learning about how things really are. Much of this criticism arises from Plato’s doctrine that there is a sharp distinction between sensory perception and cognition. (He provided arguments for this view in the first half of The Republic.) Art succeeds by rewarding sense perception rather than intellect. Pay attention to what he says about music in the following excerpt. Music always accompanied Greek theater, including the narration of poems such as The Iliad and The Odyssey. (For a parallel today, think of the music soundtrack of films.) Plato complains that this practice is a kind of artificial sweetening, producing pleasure that makes the audience agreeable to stories that would otherwise be rejected as trite or shallow. Strip away the aesthetic properties that make storytelling attractive, and what’s left is a fiction that has no value. Like Leo Tolstoy (see Chapter 3), Plato denies that the pleasure we get from this activity is sufficient to justify it.

Eduard Hanslick made a point that is applicable here. (See Chapter 4.) Hanslick proposed that in addition to being typical of artworks, artistic value should be uniquely advanced by artworks. Otherwise, it’s not artistic value, and art isn’t special. In locating artistic value with cognitive improvement, cognitivism must demonstrate that art makes an indispensable contribution to processes of discovery, thinking, and learning.

The excerpt from Plato seems to make the same point, and argues that art is dispensable. Cognitivism appears to place science and art into direct competition, but then art is the loser, because it teaches us less. Scientists, not artists, taught us that many diseases are caused by bacteria, viruses, and inherited conditions. Scientists, not artists, are going to determine how to feed the planet when major crop lands vanish due to global climate change. Plato complains that artists create fictions about doctors and other knowledgeable people without first understanding what is really happening in their field of expertise. Artists are satisfied with superficial appearances, and they keep the audience at that level, too. If art provides any cognitive training, it trains us to be satisfied with minimal understanding, poorly equipped to distinguish between “imitation” and reality. Therefore, Plato regards art as an inferior method for sharing information. Art encourages us to accept appearances as a substitute for understanding.

Worse yet, many great artworks are full of outright lies. To update Plato’s examples, we might note that vampire stories became highly popular in the 19th century, and there were many novels about vampires. (See Figure 5.3.) Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) is a fine novel, and Francis Ford Coppola made a good film from it. But if we left it to artists, people with the inherited enzyme disorder of porphyria would still be classified as vampires and their “treatment” would consist of a stake through the heart.

A classic response to Plato emphasizes that there is a difference between fiction and lies. Many cognitivists stress that the audience is aware of the difference. Liars aim to manipulate us by getting us to believe things that are not true. However, artists are not liars. They have no such goal. Writing a “defense of poetry” in 1544, the English poet Sir Philip Sidney argued that artists appeal to imagination without expecting us to believe any of it. Sidney adopts the traditional assumption that all art requires some processing in imagination. He proposes that audiences are aware when they are being asked to imagine something rather than believe it. If one is not expected to believe what is said, it cannot be a lie. Sidney says,

Now for the poet, he nothing affirms, and therefore never lies: for as I take it, to lie, is to affirm that to be true, which is false. So … the historian, affirming many things, can … hardly escape from many lies. But the poet as I said before, never affirms, the poet never makes any circles about your imagination to conjure you to believe for true what he writes. … yet because he tells them not for true, he lies not.

However, if art does not aim to convey truth, where is the cognitive benefit? Plato is especially worried about the effect of fiction on children, who are not in a position to understand that, in art, “the poet … never affirms” what is said.

Following Sidney, many supporters of art’s cognitive value emphasize the unique benefits of imaginative engagement with fiction. Imagination is our capacity to explore ideas without affirming them. Thus, art invites us to attend to possibilities and alternatives. Affirming none of them, it tells no lies. As the character Hamlet says in Shakespeare’s play of that name, “There are more things in heaven and earth … Than are dreamt of in your philosophy” (Hamlet, Act 1, Scene 5). Art, and narrative art especially, invites imaginative engagement that makes us vividly aware of possibilities that would not otherwise occur to us. Today, art is often praised for exercising the imagination.

This argument assumes, of course, that there is cognitive benefit in being more open minded and more imaginative. Not so for Plato! Instead, we should exercise the intellect (“intelligence” in the translation found below). In Plato’s formulation, the intellect processes and scrutinizes whatever is given by to us in sense perception. The rational power of the mind interrogates this information for consistency (employing “measurement and reckoning”). If we subject our observations of the world to rational examination and correction, we do not know what is really going on around us. It is no accident that calculation and measurement are the intellectual skills that are central to the scientific method. Plato understood imagination as any thought process that is not governed by intelligence. Imagination is aligned with irrationality and sense perception. Therefore, artistic value is friendly to imagination and the acceptance of lies, rather than discovery of truth and reality.

If the opening line of the following excerpt puzzles you, remember what was stressed in Chapter 1. This document was written in ancient Greek, and any English translation of Plato that references “artists” updates the text to conform to how we would say it today. However, Plato has no way to reference “artists” as a special class of people. In ancient Greek, the category referenced in this text by Plato is more literally “maker of handcrafts” (i.e., anyone who made things by hand). Their word did not differentiate between a carpenter and a sculptor, or between a blacksmith and a portrait painter. Struggling to make this distinction, Plato begins this excerpt with the proposal that there is a special subset of craftsmen whose work is very different from the work of cobblers, bakers, and candle-stick makers. This special group makes illusions or “phantasms.” Today, we might refer to this group as visual-content creators. Plato focuses on them, and not the larger set of “makers” that the Greeks called artists (i.e., crafts people). Having singled out visual-content creators, he then has to introduce poets and musicians separately, as a group that supplements visual artists. Poets and musicians do not literally make things, so it was awkward to call them “craftsmen” in ancient Greek. Consequently, the discussion starts with visual artists before moving on to Homer and poetry, at which point Plato finally introduces a term for the whole group he’s discussing: “imitators.”

Plato. Excerpt from The Republic, Book 10. (ca. 375 B.C.E.)

Translated by Paul Shorey (1935, Public Domain), amended and reset with alternating speakers

Socrates: what name you would give to this [other] craftsman?

Glaucon: Which one?

Socrates: One who makes all the things that all handicraftsmen produce.

Glaucon: A truly clever and wondrous man you tell of!

Socrates: Ah, but wait, and you will say so indeed, for this same handicraftsman is not only able to make all crafted items, but he produces all plants and animals, including himself, and thereto earth and heaven and the gods and all things in heaven and in Hades under the earth.

Glaucon: A most marvellous sophist.

Socrates: Are you are incredulous? Tell me, do you deny altogether the possibility of such a craftsman, or do you admit that in a sense there could be such a creator of all these things, and in another sense not? Or do you not perceive that you yourself would be able to make all these things in a way?

Glaucon: And in what way, I ask you?

Socrates: There is no difficulty, but it is something that the craftsman can make everywhere and quickly. You could do it most quickly if you should choose to take a mirror and carry it about everywhere. You will speedily produce the sun and all the things in the sky, and speedily the earth and yourself and the other animals and implements and plants and all the objects of which we just now spoke.

Glaucon: Yes, [but that is] the appearance of them, but not the reality and the truth.

Socrates: Excellent. and you come to the aid of the argument opportunely. For I take it that the painter too belongs to this class of producers, does he not?

Glaucon: Of course.

Socrates: But you will say, I suppose, that his creations are not real and true. And yet, after a fashion, the painter too makes a couch, does he not?

Glaucon: Yes, the appearance of one, he too. …

Socrates: Consider, then, this very point. To which is painting directed in every case, to the imitation of reality as it is or of appearance as it appears? Is it an imitation of a phantasm or of the truth?

Glaucon: Of a phantasm.

Socrates: Then the mimetic art is far removed from truth, and this, it seems, is the reason why it can produce everything, because it touches or lays hold of only a small part of the object and that a phantom; as, for example, a painter, we say, will paint us a cobbler, a carpenter, and other craftsmen, though he himself has no expertness in any of these arts, but nevertheless if he were a good painter, by exhibiting at a distance his picture of a carpenter he would deceive children and foolish men, and make them believe it to be a real carpenter

Glaucon: Why not? …

Socrates: When anyone reports to us of someone, that he has met a man who knows all the crafts and everything else that men severally know, and that there is nothing that he does not know more exactly than anybody else, our tacit rejoinder must be that he is a simple fellow, who apparently has met some magician or sleight-of-hand man and imitator and has been deceived by him into the belief that he is all-wise, because of his own inability to put to the proof and distinguish knowledge, ignorance and imitation.

Glaucon: Most true. …

Socrates: Shall we, then, lay it down that all the poetic tribe, beginning with Homer, are imitators of images of excellence and of the other things that they ‘create,’ and do not lay hold on truth? but, as we were just now saying, the painter will fashion, himself knowing nothing of the cobbler’s art, what appears to be a cobbler to him and likewise to those who know nothing but judge only by forms and colors?

Glaucon: Certainly.

Socrates: And similarly, I suppose, we shall say that the poet himself, knowing nothing but how to imitate, lays on with words and phrases the colors of the several arts in such fashion that others equally ignorant, who see things only through words, will deem his words most excellent, whether he speak in rhythm, meter and harmony about cobbling or generalship or anything whatever. So mighty is the spell that these adornments naturally exercise; though when they are stripped bare of their musical coloring and taken by themselves, I think you know what sort of a showing these sayings of the poets make. For you, I believe, have observed them.

Glaucon: I have …

Socrates: Yet still he will none the less imitate, though in every case he does not know in what way the thing is bad or good. But, as it seems, the thing he will imitate will be the thing that appears beautiful to the ignorant multitude.

Glaucon: Why, what else?

Socrates: On this, then, as it seems, we are fairly agreed, that the imitator knows nothing worth mentioning of the things he imitates, but that imitation is a form of play, not to be taken seriously. … In heaven’s name, then, this business of imitation is … removed from truth, is it not?

Glaucon: Yes.

Socrates: And now again, to what element in [the mind] is its function and potency related?

Glaucon: Of what are you speaking?

Socrates: Of this: The same size, I presume, viewed from near and from far does not appear equal?

Glaucon: Why, no.

Socrates: And the same things appear bent and straight to those who view them in water and out, or concave and convex, owing to similar errors of vision about colors, and there is obviously every confusion of this sort in our souls. And so scene-painting in its exploitation of this weakness of our nature falls nothing short of witchcraft, and so do jugglery and many other such contrivances.

Glaucon: True.

Socrates: And have not measuring and numbering and weighing proved to be most gracious aids to prevent the domination in our [understanding] of the apparently greater or less or more or heavier, and to give the control to that which has reckoned and numbered or even weighed?

Glaucon: Certainly.

Socrates: But this surely would be the function of the part of the [mind ]that reasons and calculates.

Glaucon: Why, yes. …

Socrates: But, further, that which puts its trust in measurement and reckoning must be the best part of the soul.

Glaucon: Surely.

Socrates: Then that which opposes it must belong to the inferior elements of the soul.

Glaucon: Necessarily.

Socrates: This, then, was what I wished to have agreed upon when I said that poetry, and in general the mimetic art, produces a product that is far removed from truth in the accomplishment of its task, and associates with the part in us that is remote from intelligence, and is its companion and friend for no sound and true purpose.

Glaucon: By all means.

Socrates: Mimetic art, then, is an inferior thing cohabiting with an inferior and engendering inferior offspring.

Glaucon: It seems so.

Socrates Does that hold only for vision or does it apply also to hearing and to what we call poetry?

Glaucon: Presumably, to poetry also. …

5.3. Kant on Cognition and Art

Plato’s argument that art cannot lead us toward truth captures the key challenge to a cognitivist theory of artistic value. In brief, it says that visual art and storytelling (literature and theater) are interesting to us because they stimulate the senses and the imagination, but this is harmful because it rewards sense perception and imagination at the expense of truth. Plato and his many followers say that we only arrive at truth when we achieve a clear, objective conceptual grasp of the world. However, art does nothing to help us to achieve this objective clarity. This tension between (1) stimulating the senses and imagination and (2) developing greater insight into reality is Plato’s key evidence that art lacks cognitive value.

If that is so, where are the cognitive benefits?

In the 18th century, Immanuel Kant was concerned about the same gap between what we sense and what we know. One of Kant’s main teachings is that empirical knowledge is limited by the inherent limitations of the human mind. Science provides us with a lot of useful empirical knowledge, such as the fact that the boiling point of water varies according to altitude and air pressure. However, the mind naturally speculates about matters that science cannot penetrate, such as the nature of good and evil. Furthermore, there may be dimensions of reality that are beyond the scope of the scientific method. As humans, we cannot help but speculate about topics that are beyond the reach of science.

For Kant, the value of art is that it provides a method for exploring these speculative topics. Art does this by merging the seemingly distinct realms of sensation, imagination, and conceptual thought. For Kant, art’s cognitive value is explained by art’s power to bring these mental processes together in a valuable way. This proposal is found in his doctrine of aesthetic ideas.

The core of the theory is that art is cognitively valuable for providing new insights, rather than teaching facts. Revived in the 20th century, this doctrine known as neo-cognitivism. Art’s cognitive value is found in its enrichment of our thinking, rather than teaching us truths about the world. The following explanation of Kant emphasize his alignment with contemporary neo-cognitivism, and the excerpt is edited in a manner that leaves out some details that tend to obscure this alignment.

Put briefly, Kant is a neo-cognitivist because he supports the view that successful artworks supply symbols that encourage us to engage in complex thinking. He proposes that art is a form of communication that functions by taking an abstract topic and presenting it indirectly and symbolically. It does this by making metaphorical associations that arise when an abstraction is linked to something that is concrete, specific, and familiar. In Kant’s terminology, abstractions are “ideas.” Two of his examples are eternity and the creation of the universe. Humans can think more clearly about concrete things — things we can directly perceive — than about abstractions. Concrete things are variously described as perceptible, sensory, empirical, or, using the ancient Greek term, aesthetic. When someone communicates about an abstraction by relating it to familiar perceptible things, they create an aesthetic idea. This process also works with concepts that we struggle to define, such as love, death, and evil.

So, basically, an aesthetic idea involves two things. (1) It takes an abstract, speculative idea and (2) relates it to something concrete and familiar. By doing so, the artist encourages the audience to engage in imaginative “play” with the idea, exploring multiple suggestions and associations that arise from the interplay of the idea and its indirect representation. This approach grants that we cannot expect to pin down any truths in an encounter with art. That task is the job of empirical science. However, because artistic symbolism deals with ideas that science cannot handle, we receive a cognitive benefit from art in the form of imaginative exploration of deeper human concerns.

A classic example is imagery in which the Christian God is presented as a bearded, white-haired old man. (See Figure 5.5.) This is the technique of personification, or presenting something that is not human as being human. In one of the famous images that Michelangelo devised for the Sistine Chapel at the Vatican, an old man is supported in the sky by angels. He stretches out his arm and, with the touch of his finger, brings Adam to life on the solid ground of the earth. Illustrating the story from the book of Genesis about the creation of the world and the first people, Michelangelo shows God reaching out from the heavens and Adam reaching back, capturing the Judeo-Christian teaching that we are made in God’s image. This is a classic example of an aesthetic idea.

Kant offers very few examples. At one point, he quotes a few lines from a poem by Frederick the Great that speaks of the last rays of sunlight at sunset. Kant’s point is that sunsets are not the real topic. The poem is actually about death, and how one’s last breath is like the last ray of light at sunset. The poem encourages the reader to mentally picture a sunset and, using the image constructed in imagination, to then imagine additional associations between death and sunsets. Thinking about parallels between the two topics offers new ways to think about death. (For example, the sunset isn’t the end of the sun, since it will return tomorrow, so perhaps death is a pause before reincarnation.)

Although Kant does not use the term “metaphor,” it is clear that metaphors are one of the symbolic categories that he has in mind. In this respect, his doctrine is actually very ancient. Aristotle’s short book on theater, the Poetics, was written more than 2,000 years earlier. Yet it expresses the same core idea: “The greatest thing by far is to have a command of metaphor. This alone cannot be taught to one; it is a mark of natural genius, for to make good metaphors is to see similarities among difference.” (Aristotle, Poetics, translation F. Ferguson, modified.) Because Kant also thinks that the production of new aesthetic ideas is the primary power of artistic genius, his view dovetails neatly with Aristotle. So, this type of cognitivism has been endorsed since ancient times.

In summary, a successful artwork will not produce any precise, literal message. Instead, the best artworks have open-ended meanings, creating “ineffable” or unconstrained content. Artworks do not exist to convey specific truths about the world. Because they do not tell us “this is how things are,” their cognitive value is very different from the cognitive value of a science textbook or a newspaper article.

The key point is that the cognitive value of art is its special capacity to explore subject matter that is highly abstract (by yoking it to tangible images) or highly speculative (such as topics relating to religion and ethics). In using concrete imagery to explore associations among complex and abstract ideas, artworks require the audience to employ both imagination and understanding.

As such, artworks also have cognitive value in keeping the mind alive and alert by exercising both imagination and understanding. To put it in modern terms, responding to art is a whole-brain activity.

Since Kant offers so few examples, here are four more, three of them drawn from art made after Kant’s lifetime. The first pair explore the topic of time, and the second pair explore the topic of death.

The first example is Emily Dickinson’s poem, “A Clock Stopped” (1861). Here are the opening and closing parts of a four-verse poem:

A clock stopped — not the mantel’s;

Geneva’s farthest skill

Can’t put the puppet bowing

That just now dangled still …

The shopman importunes it,

While cool, concernless No

Nods from the gilded pointers,

Nods from seconds slim,

Decades of arrogance between

The dial life and him.

(From Poems by Emily Dickinson, edited M. L. Todd, 1911. Public Domain.)

Using the clock to stand for time, Dickinson uses a technique similar to personification. Geneva is a city in Switzerland famous for its clock makers. So, the clock is stopped because it’s broken (the experts cannot get it moving again.) Since time has stopped, a dangling puppet on strings does not move, either. The shop keeper begs the clock to start up again, but it has no concern for his wishes. “The dial life” asks us to make an association with the clock face and life, suggesting that because it has stopped moving, so has the the life of the shop keeper. While the short poem is rich in numerous associations, the overall idea is that our life is of an unknown duration, and we are arrogant to think we are in control of our time.

For neo-cognitivisists, a further value of art is that different artists create different aesthetic ideas relating to the same concept. As such, art shows us that there is no one right way to think about time, nor a right way to determine how the value of one moment compares to others. Consider how our relationship to time takes on a totally different significance in a second example, namely the famous final lines at the end of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925). Here are the book’s closing lines:

Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter — tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms further… And one fine morning —

So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

(The green light is a light on a dock that Gatsby sees across the bay from his house on the shore of Long Island, New York.)

Dickinson invites us to understand our experience of time in one way; Fitzgerald, in another way.

To be clear, short bits from famous literary works do not possess cognitive value by themselves. It is only in relation to the totality of the whole work that these key phrases crystalize our thought processes, allowing individual lines or short passages to act as a lens for looking at life events that might otherwise seem unconnected or random. But because the application of these lines to representative experiences will group those events and experiences together in a memorable way, the controlling image of a literary work can become a touchstone for understanding our lives. But they remain open-ended as organizing symbols, always permitting new associations to complicate the artistic symbol (the aesthetic idea).

As suggested by the example of Michelangelo’s images in the Sistine Chapel, this approach to cognitive value is common in the visual arts. Consider the tradition of 17th- and 18th-century Dutch still-life flower paintings. However, the subject is not really flowers. Like Dickinson’s clock and the poem that Kant quotes about sunsets, these paintings are exploring the topic of death.

Typically, these Dutch paintings group together flowers that bloom at different times of the spring and summer. Therefore, the pictured bouquet cannot ever be seen in real life. The painter creates an imaginary scene. Where Plato would criticize this deviation from truth, the neo-cognitivist thinks it is a stepping stone into the fiction’s symbolic richness.

The details contribute to the theme. If you study a still life by Clara Peeters (see figure 5.6), you will see that insects have chewed some of the leaves. The tulips are wilting and falling over. Some petals have fallen to the table. Having been cut for display, these flowers are in the process of dying. A butterfly perches on a flower stem. But if the butterfly lays its eggs here, instead of on a living plant, its efforts will be in vain.

Paintings of this type are classified as examples of Memento mori (Latin, meaning “remember you must die”). The painting is not about flowers at all. It is about the impending death of the viewer, and every detail of the imaginary scene contributes an associated “attribute” of the progression from youth and health to aging and death. For Kant, these paintings are, literally, aesthetic ideas, enriching the empirical content with associations and implications that range far beyond what is presented in the picture. The best art maximizes the number of associations presented by the symbolic content, making the work as rich as possible. Because it works through language, Kant proposes that poetry is the art form most capable of achieving this goal. Other cognitivists, such as the 20th-century philosopher Nelson Goodman, argue that pictures are symbolically denser and richer than literature.

The fourth example is Winslow Homer’s The Veteran in a New Field, and it is another artwork about death. (See figure 5.7.) It was painted in 1865, just after the Civil War ended. Homer rose to fame as a war illustrator, producing many images of the Civil War for northern magazines. In this case, the linguistic element of the title combines with the pictorial representation to enrich the symbolism.

The expression “a new field” in the title raises an obvious question. What is the old field that is being contrasted with the new? This farmer is a veteran, which means he has just ended his service in the war. The “old” field is the killing fields, i.e., the battlefields he has left behind. The American Civil War was the deadliest in U.S. history, and we are invited to imagine that this veteran saw endless suffering and death. After three or four years away, he is now safe back home, reaping wheat. Many of the battles of the war took place in open fields like this one. He holds an old-fashioned scythe, the same tool that American symbolism gives to the grim reaper. So the scythe suggests that he was a kind of grim reaper, responsible for the deaths of Confederate soldiers. (Because it’s wheat, he’s in the north, not the south.) As he mows down the hay, he cannot help but think of the men he mowed down. He is almost certainly suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which in 1865 was known as “soldier’s heart” and “nostalgia.” Winslow Homer has created a powerful aesthetic idea: a superficially pleasant scene is an image loaded with associations of America at war with itself, and about the sacrifices that the men of the north made to end the institution of slavery and to advance justice.

However, Chapter 4 of this book raised the long-standing worry that one of the major art forms appears to lack cognitive value. Hanslick argued that instrumental music teaches us nothing. It explores no ideas. It does not make us better people. Therefore, if Vivaldi’s Concerto for Violin in G Minor (RV 319) is typical of instrumental music in failing to possess cognitive value, then cognitivism fails as a general theory of artistic value. Although some instrumental music is jaw-droppingly brilliant in its complexity, there is no plausible explanation of how the music provides more cognitive value than the non-pictorial visual complexities of a Persian rug. The value is purely aesthetic, and we seem to have a major art form that is unlike all the rest. Kant actually made this very point many decades before Hanslick. Kant was willing to accept the implication that instrumental music has little or no cognitive value. (Music with words is different. It is cognitively valuable because it takes verbal representations and makes them more complex.) Comparing carpet patterns and instrumental music as more or less the same thing in two different media, Kant concludes that instrumental music is decorative. It is the most trivial of the arts, because it does not generate aesthetic ideas.

Immanuel Kant: Excerpt from The Critique of Judgment (1790), translation by J. H. Bernard (with small modifications)

Aesthetic Ideas Stimulate the Cognitive Faculties

We say [some art is] beautiful art, however they are without spirit [they have no soul] although we find nothing to blame in them on the score of taste. A poem may be very neat and elegant, but without spirit. A history may be exact and well arranged, but without spirit. A [celebration] discourse may be solid and at the same time elaborate, but without spirit. … What then do we mean by spirit?

Spirit [or soul], in an aesthetic sense, is the name given to the animating principle of the mind. But that whereby this principle animates the mind, … into such a play as maintains itself and strengthens the [mental] powers in their exercise.

Now I maintain that this principle is no other than the faculty of presenting aesthetic ideas. And by an aesthetic idea I understand a representation of the imagination which occasions much thought, without, however, any definite thought, i.e. any definite concept, being capable of being adequate to it; it consequently cannot be completely compassed and made intelligible by language. [It cannot be adequately paraphrased] …

The imagination (as a productive mental power) is very powerful in creating another nature, as it were, out of the material that actual nature gives it. We entertain ourselves with it when experience proves too commonplace, and by it we remold experience … so that the material which we borrow from nature in accordance with this law can be worked up into something different which surpasses nature.

Such representations of the imagination we may call ideas, partly because they at least strive after something which lies beyond the bounds of experience, and so seek to approximate to a presentation of [theoretical] concepts … The poet ventures to realise to sense, rational ideas of invisible beings, the kingdom of the blessed, hell, eternity, creation, etc.; or even if he deals with things of which there are examples in experience, — e.g. death, envy and all vices, also love, fame, and the like, — he tries, by means of imagination … to go beyond the limits of experience and to present [these ideas] to Sense with a completeness of which there is no example in nature.

It is, properly speaking, in the art of the poet, that the faculty of aesthetic ideas can manifest itself in its full measure. But this faculty, considered in itself, is properly only a talent (of the imagination).

If now we [communicate such a concept by using a] representation of the imagination … but which occasions solely by itself more thought than can ever be comprehended in a definite concept, and which therefore enlarges the concept aesthetically [i.e., in a sensory manner], in an unbounded fashion, — the imagination is here creative, and it brings the faculty of intellectual ideas [our power to create theories] into movement; i.e. a movement, occasioned by a representation, towards more thought (though belonging, no doubt, to the concept of the object) than can be grasped in the representation or made clear.

Those forms … express the consequences [i.e., attributes] bound up with it and its relationship to other concepts. … Thus Jupiter’s eagle with the lightning in its claws is an attribute of the mighty king of heaven, as the peacock is of its magnificent queen.

These aesthetic attributes do not, like logical attributes, represent what lies in our concepts of the sublimity and majesty of creation, but something different, which gives occasion to the imagination to spread itself over a number of kindred representations, that arouse more thought than can be expressed in a concept determined by words. They furnish an aesthetic idea, which … takes the place of logical presentation; and thus as their proper office they enliven the mind by opening out to it the prospect into an illimitable field of kindred representations. But beautiful art does this not only in the case of painting or sculpture (in which the term “attribute” is commonly employed): poetry and rhetoric also get the spirit that animates their works simply from the aesthetic attributes of the object, which accompany the logical and stimulate the imagination, so that it thinks more by their aid, although in an undeveloped way, than could be comprehended in a concept and therefore in a definite form of words. — For the sake of brevity I must limit myself to a few examples only.

When Frederick the Great in one of his poems expresses himself as follows:

“the star of the day at the end of its career,

Spreads a soft light on the horizon;

And the last rays it darts into the air,

Are the last breaths he gives to the universe”

he quickens his rational idea of a cosmopolitan disposition at the end of life by an attribute which the imagination (in remembering all the pleasures of a beautiful summer day that are recalled at its close by a serene evening) associates with that representation, and which excites a number of sensations and secondary representations for which no expression is found.

On the other hand, an intellectual concept may serve conversely as an attribute for a representation of sense and so can quicken this latter by means of the idea of [something that cannot be known to the senses]. Thus, for example, Johann Philipp Withof says, in his description of a beautiful morning:

“The sun arose

As calm from virtue springs.”

The consciousness of virtue, even if one only places oneself in thought in the position of a virtuous man, diffuses in the mind a multitude of sublime and restful feelings and a boundless prospect of a joyful future, to which no expression measured by a definite concept completely attains.

In a word, the aesthetic idea is a representation of the imagination associated with a given concept, which is bound up with such a multiplicity of partial representations in its free employment, that for it no expression marking a definite concept can be found; and such a representation, therefore, adds to a concept much ineffable thought, the feeling of which quickens the cognitive faculties, and with language, which is the mere letter, binds up spirit also.

The mental powers, therefore, whose union (in a certain relation) constitutes genius are imagination and understanding. Employing the imagination [to enhance] cognition, imagination submits to the constraint of the understanding and is subject to the limitations of understanding, making it conformable to understanding. On the other hand, in an aesthetical point of view it is free to furnish unsought, over and above that agreement with a concept, abundance of undeveloped material for the understanding; to which the understanding paid no regard in its concept, but which it applies, though not objectively for cognition, yet subjectively to quicken [i.e., enliven, stimulate] the cognitive powers and therefore also indirectly to cognitions. … The latter talent is properly speaking what is called spirit; for to express the ineffable element in the state of mind implied by a certain representation and to make it universally communicable — whether the expression be in speech or painting or statuary — this requires a faculty of seizing the quickly passing play of imagination and of unifying it in a concept (which is even on that account original and discloses a new rule that could not have been inferred from any preceding principles or examples), that can be communicated without any constraint [of rules].