3 Art and Emotion

Theodore Gracyk

Key Takeaways for Art and Emotion

Topic: Are the arts of value as the expression of human emotion?

The doctrine that all of the arts are concerned with expression of emotion is relatively recent

This doctrine has taken multiple forms

The idea of art as self-expression is one of the more recent forms of this doctrine

A strong version of this doctrine proposes that good art transfers the artist’s emotions to the audience

As defended by Leo Tolstoy, this position reconfigured what counts as genuine art

Some major poets, such as John Keats and T.S. Eliot, have denied the relevance of self-expression

“Expression” of emotion can be explained without reference to self-expression

Shakespeare again serves as an interesting test case

3.1. Introduction to Chapter 3

Chapter 1 discusses Charles Batteux’s attempt to give a comprehensive definition of the fine arts. His definition includes both representation and beauty. However, Batteux admits that dance and instrumental music cannot provide realistic, recognizable representations of most things in the world. Looking at a picture of a tree, most people can see the tree in the picture without having to be told what is pictured. The same is not true for most instrumental music, or for ballet. A melody or a dance is unlikely to be recognized as a tree. Without a text to guide them, people cannot recognize what is represented. Recognizing this difference, Batteux proposes that music and dance are limited in what they represent. They specialize. They are restricted to providing “a portrait of the human passions,” that is, of human emotions. He does not say the same thing about painting, literature, sculpture, or architecture.

Beginning toward the end of the 18th century, some European intellectuals began to promote the idea that every art provides “a portrait of the human passion.” All of the fine arts, not just music and dance, are distinguished from other human creative activity by being representations of human emotional life. The expression of emotion is a necessary component of every artwork.

This view is known as the expression theory of art. It became widespread in the 19th century.

This basic idea has been developed in three distinct ways.

- Self-expression theory: Every successful work of art reveals the emotional life of the artist who creates it. All art is a kind of autobiography, because it portrays emotions felt by the artist.

- Infection theory: Every successful work of art produces specific emotions in its audience. It is more important to feel something in response to art than to think about it. Sometimes, but not always, this idea is conveyed by saying that art should move us to feel whatever emotion inspired the artist. (In Section 3.2 below, Leo Tolstoy speaks of infection. In Section 3.3, T.S. Eliot describes the same process as arousal. Take note of the difference between the two metaphors.)

- Objective correlative theory: A successful work of art will objectively represent emotion, but that emotion does not have to be the artist’s own emotion and it does not have to move the audience emotionally. This is the version of of expression theory that most clearly aligns with the idea of giving a “portrait” of emotion. For example, sad music is sad in the same way that a picture of a tree represents a tree, that is, by showing what it is like in some important respects.

Here is a poem by Emily Dickinson. (She did not title her poems.) We can get a sense of the different theories about art and emotion by applying them to this poem.

If I can stop one heart from breaking,

I shall not live in vain;

If I can ease one life the aching,

Or cool one pain,

Or help one fainting robin

Unto his nest again,

I shall not live in vain.

(From Poems by Emily Dickinson, edited by M. L. .Todd and T. W. Higinson, 1890. Public Domain.)

This is a poem about sympathy. More specifically, it is about the value of sympathy in human life. The most demanding version of art as expression is a theory that combines the requirements of (1) self-expression and (2) infection by that same emotion. On this view, Dickinson’s poem is an artwork only if she is being honest about feeling sympathy for the people around her. But that is not sufficient. In addition, it must produce that same feeling in others. Although the poem’s meaning might not be immediately clear to everyone today, the average person who works it out and understands the poem is supposed to feel some corresponding sympathy when they understand the message. If one or both of the two conditions is not met (either because the poet is not sincere, or no one is moved by it), then it is a failure. This view of art and emotion was famously promoted by the Russian novelist, Leo Tolstoy. In fact, he argues that if it fails in either of the two requirements, then it is worse than failed art. It is not art at all.

But does it really matter if Dickinson is sincere and writing about herself? According to the poet John Keats, self-expression is irrelevant. If the self-expression theory is correct and all good art is autobiographical, then artists are forced to restrict themselves to a narrow range of subject matter. Given that different people have very different personalities, the self-expression theory seems to deny the possibility that a writer can successfully convey the emotional life of a character who is different from themselves. But, says Keats, it is clear that many writers succeed in creating characters who are very different from themselves. Therefore, it is better to think of a successful poet as a “chameleon” who suppresses their own personality in order to be able to mimic the personalities of others. The poet succeeds because of their interest in other people, not because they engage in soul-searching about themselves. Keats makes a dig at William Wordsworth, who popularized the idea that all expressive art is a kind of autobiography. Keats recognizes that some artists are primarily concerned with “Wordsworthian” self-expression, but Keats suggests that they are egotistical and have no real interest in making good art. As an artist, Keats reports, his goal is to create beautiful poems, and this goal is unrelated to self-expression.

John Keats, Letter to To Richard Woodhouse, 1818

As to the poetical Character itself (I mean that sort of which, if I am any thing, I am a member; that sort distinguished from the Wordsworthian or egotistical sublime; which … stands alone) it is not itself — it has no self — it is every thing and nothing — It has no character — it enjoys light and shade; it lives in gusto, be it foul or fair, high or low, rich or poor, mean or elevated — It has as much delight in conceiving an Iago as an Imogen. What shocks the virtuous philosopher, delights the chameleon poet. It does no harm from its relish of the dark side of things any more than from its taste for the bright one; because they both end in speculation. A poet is the most unpoetical of any thing in existence; because he has no Identity — he is continually in for — and filling some other body — The sun, the moon, the sea and men and women who are creatures of impulse are poetical and have about them an unchangeable attribute — the poet has none; no identity — he is certainly the most unpoetical of all God’s creatures. If then he has no self, and if I am a poet, where is the wonder that I should say I would write no more? Might I not at that very instant have been cogitating on the characters of [the Roman god] Saturn and [his wife] Ops? It is a wretched thing to confess; but is a very fact that not one word I ever utter can be taken for granted as an opinion growing out of my identical nature — how can it, when I have no nature? When I am in a room with people if I ever am free from speculating on creations of my own brain, then not myself goes home to myself: but the identity of every one in the room begins so to press upon me that I am in a very little time annihilated — not only among men; it would be the same in a nursery of children: I know not whether I make myself wholly understood: I hope enough so to let you see that no despondence is to be placed on what I said that day.

In the second place I will speak of my views, and of the life I purpose to myself. I am ambitious of doing the world some good: … All I hope is that I may not lose all interest in human affairs — that the solitary indifference I feel for applause even from the finest spirits, will not blunt any acuteness of vision I may have. I do not think it will — I feel assured I should write from the mere yearning and fondness I have for the beautiful even if my night’s labours should be burnt every morning, and no eye ever shine upon them. But even now I am perhaps not speaking from myself: but from some character in whose soul I now live.

Applying these ideas to Dickinson, Keats is saying that the poem is a good one if she gets others to understand (rather than experience) the character of a person who has a strong sense of sympathy. The important work of poets and other artists is their ability to capture and display people’s emotional lives, and it is possible to do this without engaging in self-expression. As such, we don’t have to ask how the poem relates to Dickinson’s life to know whether it is a good poem. So, this shows that self-expression theory is a bad way to think about expression in most art.

However, if art does not require self-expression, then perhaps it does not require the audience to feel anything in response. It might be enough that Dickinson selected familiar things in the world (heartbreak, misery, and an injured bird) that together call attention to the importance of sympathy in human affairs. The poem shows us something about human emotions, and that by itself is enough to make it art. In Section 3.3, the poet T.S. Eliot defends this sort of theory in his doctrine artworks provide an objective correlative of emotion. (Stressing understanding as the goal, this position is a version of the cognitive theory discussed in Chapter 5 of this book.)

3.2 Tolstoy and Infection of Emotion

Tolstoy explains the power of art by comparing it to an infectious disease. In the same way that some diseases can infect others who are in close proximity, some human behaviors “infect” other people. He says that art is emotionally “contagious.” One person smiles, and people smile back. A person yawns, and other people yawn, too. Modern psychology uses a different metaphor, and calls this well-known phenomenon a mirror response. Tolstoy says that the special purpose of art is to “infect” others with specific attitudes toward specific things. If you are an artist, your primary goal is to share your feelings and, by doing so, influence others to feel as you feel. Tolstoy thinks this is valuable when the feelings unite people together in a positive way. Used properly to unite people, art is one of the most valuable aspects of human life.

Tolstoy also emphasizes two things that art is not. Art is not entertainment. Entertainment is all about pleasure. But art is often unpleasant, not entertaining. Secondly, art is not the stuff made by artists. Art is fundamentally an activity of sharing emotions. The art market, which equates art with objects that can be bought and sold, has confused people about the true nature of art. For Tolstoy, a “true artistic impression” is neither entertainment nor a commodity. By rejecting the importance of getting pleasure from art, Tolstoy rejects a core assumption handed down from the ancient Greeks until the 19th century.

If one pays attention to Tolstoy’s examples, another interesting idea emerges. Tolstoy thinks that the fine arts — the kinds of things that originally motivated definitions of art — are bad examples of art. A story told to children at bed time is a better example of art than a play by Shakespeare. A folk song is better than a symphony by Beethoven. If it isn’t readily accessible to the average person, a piece of “so-called” art probably isn’t “true” art.

Excerpts from Leo Tolstoy, What Is Art?, translation by Alymer Maude (1899) with editorial modifications by T. Gracyk

CHAPTER FOUR

If we say that the aim of any activity is merely our pleasure, and define it solely by that pleasure, our definition will evidently be a false one. But this is precisely what has occurred in the efforts to define art. Now, if we consider the food question it will not occur to anyone to affirm that the importance of food consists in the pleasure we receive when eating it. Everyone understands that the satisfaction of our taste cannot serve as a basis for our definition of the merits of food, and that we have therefore no right to presuppose that the dinners with cayenne pepper, Limburger cheese, alcohol, etc., to which we are accustomed and which please us, form the very best human food. …

Just as people who conceive the aim and purpose of food to be pleasure cannot recognize the real purpose of eating, so people who consider the aim of art to be pleasure cannot realize its true meaning and purpose. Instead, they treat art as an activity related to other phenomena of life [according to a hedonistic criterion of value]. People come to understand that the meaning of eating lies in the nourishment of the body only when they cease to consider that the object of that activity is pleasure. And it is the same with regard to art. People will come to understand the meaning of art only when they cease to consider that the aim of that activity is beauty, i.e., pleasure. …

CHAPTER FIVE

In order correctly to define art, it is necessary, first of all, to cease to consider it as a means to pleasure and to consider it as one of the conditions of human life. Viewing it in this way we cannot fail to observe that art is one of the means of communication between people.

Every work of art causes the receiver to enter into a certain kind of relationship both with him who produced, or is producing, the art, and with all those who, simultaneously, previously, or subsequently, receive the same artistic impression.

Speech, transmitting the thoughts and experiences of people, serves as a means of union among them, and art acts in a similar manner. The peculiarity of this latter means of communication, distinguishing it from communication by means of words, consists in this, that whereas by words someone transmits thoughts to another, by means of art they transmits their feelings.

The activity of art is based on the fact that a person, receiving through hearing or sight another personʹs expression of feeling, is capable of experiencing the emotion which moved the one who expressed it. To take the simplest example; one person laughs, and another who hears becomes merry; or a person weeps, and another who hears feels sorrow. Someone is excited or irritated, and another person seeing them comes to a similar state of mind. By movements or by the sounds of the voice, a person expresses courage and determination or sadness and calmness, and this state of mind passes on to others. A person suffers, expressing sufferings by groans and spasms, and this suffering transmits itself to other people; a person expresses a feeling of admiration, devotion, fear, respect, or love to certain objects, persons, or phenomena, and others are infected by the same feelings of admiration, devotion, fear, respect, or love to the same objects, persons, and phenomena.

And it is upon this capacity of people to receive another person’s expression of feeling and experience those feelings himself, that the activity of art is based.

If a person infects another or others directly, immediately, by appearance or by the sounds made to vent, and does so at the very time the expression happens; if a yawning person causes another to yawn, or by laughing or crying causes another person to laugh or cry at the same time — that does not amount to art.

Art begins when one person, with the object of joining another or others in one and the same feeling, expresses that feeling by certain external indications. To take the simplest example: a boy, having experienced, let us say, fear on encountering a wolf, relates that encounter; and, in order to evoke in others the feeling he has experienced, describes himself, his condition before the encounter, the surroundings, the woods, his own lightheartedness, and then the wolfʹs appearance, its movements, the distance between himself and the wolf, etc. All this, if only the boy, when telling the story, again experiences the feelings he had lived through and infects the hearers and compels them to feel what the narrator had experienced is art. If even the boy had not seen a wolf but had frequently been afraid of one, and if, wishing to evoke in others the fear he had felt, he invented an encounter with a wolf and recounted it so as to make his hearers share the feelings he experienced when he feared the world, that also would be art. And just in the same way it is art if a painter or sculptor, having experienced either the fear of suffering or the attraction of enjoyment (whether in reality or in imagination) expresses these feelings on canvas or in marble so that others are infected by them. And it is also art if a musical composer feels or imagines feelings of delight, gladness, sorrow, despair, courage, or despondency and the transition from one to another of these feelings, and expresses the same transition between feelings by sounds so that the hearers are infected by them and experience them as they were experienced by the composer.

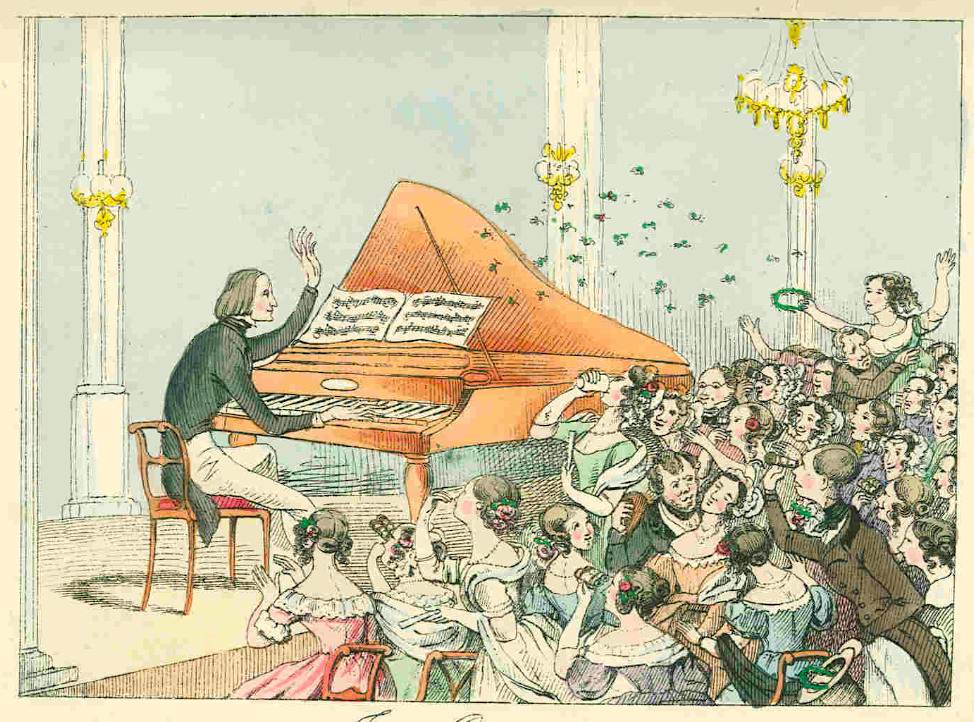

The feelings with which the artist infects others may be most various — very strong or very weak, very important or very insignificant, very bad or very good: feelings of love for oneʹs own country, self‐devotion and submission to fate or to God expressed in a drama, raptures of lovers described in a novel, feelings of voluptuousness expressed in a picture, courage expressed in a triumphal march, merriment evoked by a dance, humor evoked by a funny story, the feeling of quietness transmitted by an evening landscape or by a lullaby, or the feeling of admiration evoked by a beautiful arabesque — it is all art.

If only the spectators or auditors are infected by the feelings which the author has felt, it is art.

To evoke in oneself a feeling one has once experienced, and having evoked it in oneself, then, by means of movements, lines, colors, sounds, or forms expressed in words, so to transmit that feeling that others may experience the same feeling — this is the activity of art.

Art is a human activity consisting in this, that one person consciously, by means of certain external signs, hands on to others feelings they have lived through, and that other people are infected by these feelings and also experience them. …

If people lacked this capacity to receive the thoughts conceived by the people who preceded them and to pass on to others their own thoughts, we would be like wild beasts …

And if we lacked this other capacity of being infected by art, people might be almost more savage still, and, above all, more separated from, and more hostile to, one another.

And therefore the activity of art is a most important one, as important as the activity of speech itself and as generally diffused.

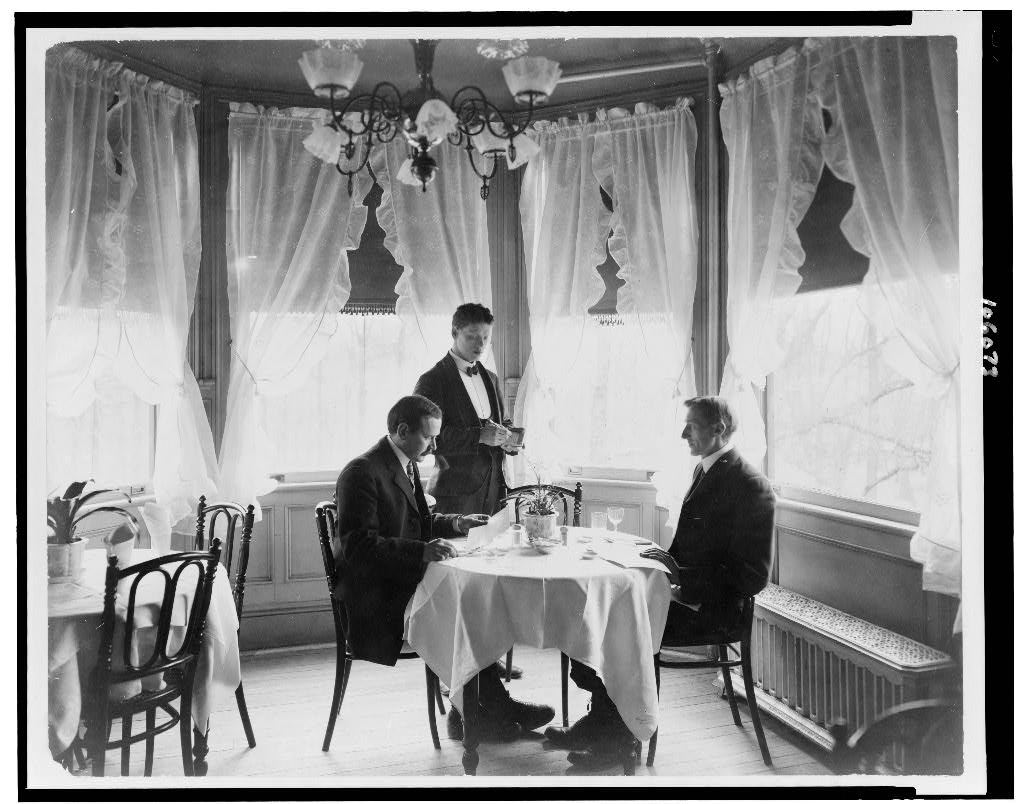

We are accustomed to understand art to be only what we hear and see in theaters, concerts, and exhibitions, together with buildings, statues, poems, novels. . . . But all this is but the smallest part of the art by which we communicate with each other in life. All human life is filled with works of art of every kind — from cradlesong, jest, mimicry, the ornamentation of houses, dress, and utensils, up to church services, buildings, monuments, and triumphal processions. It is all artistic activity. So that by art, in the limited sense of the word, we do not mean all human activity transmitting feelings, but only that part which we for some reason select from it and to which we attach special importance. …

CHAPTER EIGHT

A consideration presents itself showing that fine art cannot be the whole of art, viz., the fact that it is completely unintelligible to the people. Formerly men wrote poems in Latin, but now their artistic productions are as unintelligible to the common folk as if they were written in Sanskrit. The usual reply to this is that if the people do not now understand this art of ours it only proves that they are undeveloped, and that this has been so at each fresh step forward made by art. First it was not understood, but afterward people got accustomed to it.

Defenders of fine art say, ʺIt will be the same with our present art; it will be understood when everybody is as well educated as we are — the people of the upper classes —who produce this art.” But this assertion is [elitism], for we know that the majority of the productions of the art of the upper classes, such as various odes, poems, dramas, cantatas, pastorals, pictures, etc., which delighted the people of the upper classes when they were produced, never were afterward either understood or valued by the majority of people, but have remained what they were at first — a mere pastime for rich people of their time, for whom alone they ever were of any importance. It is also often urged, in proof of the assertion that the people will some day understand our art, that some productions of so‐called ʺclassicalʺ poetry, music, or painting, which formerly did not please the masses, do — now that they have been offered to them from all sides — begin to please these same masses; but this only shows that the crowd, especially half‐spoiled city people, can easily (its taste having been perverted) be accustomed to any sort of art. Moreover, this art is not produced by these masses, nor even chosen by them, but is energetically thrust upon them in those public places in which art is accessible to the people.

For the great majority of working‐people, fine art, besides being inaccessible on account of its costliness, is strange in its very nature, transmitting as it does the feelings of people far removed from those conditions of laborious life which are natural to the great body of humanity. That which is enjoyment to a man of the rich classes is incomprehensible as a pleasure to a working person, and evokes either no feeling at all or only a feeling quite contrary to that which it evokes in [the elite upper classes]. Such feelings as form the chief subjects of present‐day art … evoke in a working person only bewilderment and contempt, or indignation. So that even if a possibility were given to the laboring classes in their free time to see, to read, and to hear all that forms the flower of contemporary art (as is done to some extent in towns by means of picture galleries, popular concerts, and libraries), the common worker who makes a living from physical labor would be able to make nothing of our fine art. If working people did understand it, that which was understood would not elevate the soul but would certainly, in most cases, pervert it. To thoughtful and sincere people there can, therefore, be no doubt that the art of our upper classes never can be the art of the whole people. But if art is an important matter, a spiritual blessing, essential for everyone, then it should be accessible to everyone. And if, as in our day, it is not accessible to everyone, then one of two things: either art is not the vital matter it is represented to be or most of what we call art is not the real thing. …

Let us frankly admit what is the case — that our fine art is an art of the upper classes only. So essentially art has been, and is, understood by everyone engaged in it in our society. …

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

The business of art lies just in this — to make that understood and felt which, in the form of an argument, might be incomprehensible and inaccessible. Usually it seems to the recipient of a truly artistic impression that they knew the thing before but had been unable to express it.

Art, in our society, has been so perverted that not only has bad art come to be considered good, but even the very perception of what art really is has been lost. In order to be able to speak about the art of our society, it is, therefore, first of all necessary to distinguish art from counterfeit art.

There is one indubitable indication distinguishing real art from its counterfeit, namely, the infectiousness of art. If a person, without exercising effort when reading, hearing, or seeing another person’s work, experiences a mental condition which unites that person with other people who also partake of that work of art, then the object evoking that condition is a work of art. And however poetical, realistic, or interesting a work may be, it is not a work of art if it does not evoke that feeling (quite distinct from all other feelings) of joy and of spiritual union with another (the author) and with others (those who are also infected by it). …

There are people who have forgotten what the action of real art is, who expect something else form art (in our society the great majority are in this state), and that therefore such people may mistake for this aesthetic feeling the feeling of diversion and a certain excitement which they receive from counterfeits of art. But though it is impossible to undeceive these people, just as it is impossible to convince a man suffering from color blindness that green is not red, yet, for all that, this indication remains perfectly definite to those whose feeling for art is neither perverted nor atrophied, and it clearly distinguishes the feeling produced by art from all other feelings.

The chief peculiarity of this feeling is that the audience for a true artistic impression is so united to the artist that the audience feels as if the work were their own and not someone elseʹs — as if what it expresses were just what each member of the audience had long been wishing to express. A real work of art destroys, in the consciousness of the receiver, the separation between audience and artist — not that alone, but also between each individual and all others who respond to this work of art. In this freeing of our personality from its separation and isolation, in this uniting of it with others, lies the chief characteristic and the great attractive force of art.

If a person is infected by the artist’s condition of soul and feels this emotion and this union with others, then the object which has effected this is art. But if there be no such infection, if there be not this union with the author and with others who are moved by the same work — then it is not art. And not only is infection a sure sign of art, but the degree of infectiousness is also the sole measure of excellence in art.

The stronger the infection, the better is the art as art, speaking now apart from its subject matter, i.e., not considering the quality of the feelings it transmits. And the degree of the infectiousness of art depends on three conditions:

- On the greater or lesser individuality of the feeling transmitted;

- on the greater or lesser clearness with which the feeling is transmitted;

- on the sincerity of the artist, i.e., on the greater or lesser force with which the artist personally feels the emotion transmitted.

… The clearness of expression assists infection because the receiver, who mingles in consciousness with the author, is the better satisfied the more clearly the feeling is transmitted, which, as it seems to him, the receiver has long known and felt, and has only now found expression.

But most of all is the degree of infectiousness of art increased by the degree of sincerity in the artist. As soon as the spectator, hearer, or reader feels that the artist is sincere, and writes, sings, or plays as self-expression and not merely to act on others, this mental condition of the artist infects the receiver; and contrariwise, as soon as the spectator, reader, or hearer feels that the author is not writing, singing, or playing as self-expression — the artist does not personally feel what the art aims to express — but is doing it only for the receiver, a resistance immediately springs up, and the most individual and the newest feelings and the cleverest technique not only fail to produce any infection but actually repel.

I have mentioned three conditions of contagiousness in art, but they may be all summed up into one, the last, sincerity, i.e., that the artist should be impelled by an inner need to express feeling. … The more the artist has drawn it from the depths of personal experience — the more sympathetic and sincere will it be. And this same sincerity will impel the artist to find a clear expression of the feeling when transmitting it to others.

Therefore this third condition — sincerity — is the most important of the three. It is always complied with in folk art, and this explains why such art always acts so powerfully; but it is a condition almost entirely absent from our upper‐class art, which is continually produced by artists actuated by personal aims of covetousness or vanity.

Such are the three conditions which divide art from its counterfeits, and which also decide the quality of every work of art apart from its subject matter.

The absence of any one of these conditions excludes a work form the category of art and relegates it to that of artʹs counterfeits. If the work does not transmit the artistʹs peculiarity of feeling and is therefore not individual, if it is unintelligibly expressed, or if it has not proceeded from the authorʹs inner need for expression — it is not a work of art. If all these conditions are present, even in the smallest degree, then the work, even if a weak one, is yet a work of art. …

Thus is art divided from that which is not art, and thus is the quality of art as art decided, independently of its subject matter, i.e., apart from whether the feelings it transmits are good or bad.

3.3 Expressive display

Contrary to Tolstoy’s requirement of the “infectiousness of art,” many writers have insisted that it is legitimate for artists to explore emotion by creating art that simply displays the emotion. It need not be the artist’s own emotion, and it need not “infect” the audience with any emotion. Section 3.1 quoted Keats as an exponent of this simpler requirement.

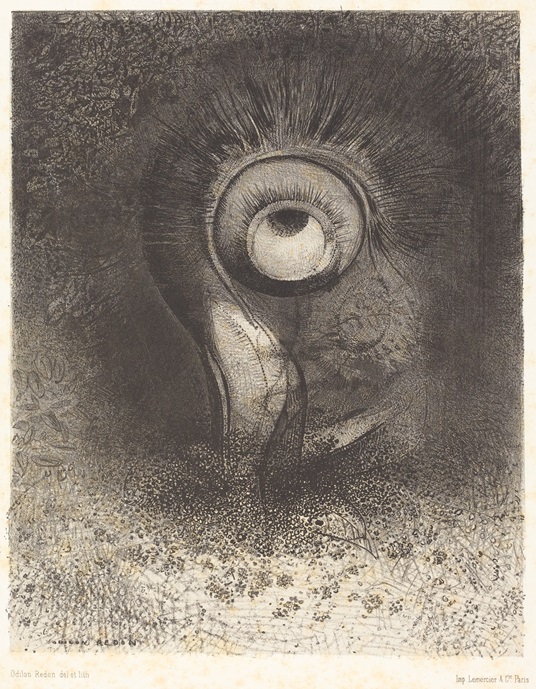

To better understand what is meant by “display” of an emotion, many writers offer examples that have nothing to do with art. In the book The Corded Shell (1981), Peter Kivy offers the example of a Saint Bernard’s face. (See figure 3.5.)

Unless its mouth is open, a Saint Bernard has a sad-looking face, that is, the face displays sadness. It looks sad because it looks the way that a human face looks when sad. Asked, “Does that dog’s face look happy?”, almost everyone will answer, “No, it looks sad.” However, there is no reason to think that the dog in the photograph is sad. For all we known, it is wagging its tail in happiness. Dogs express many of their emotions with their tails and their stance, not with facial expression. So although the Saint Bernard’s face looks sad to us, that facial expression does not reveal the dog’s emotions. Furthermore, almost everyone can recognize that the dog’s face looks sad without becoming sad in response to seeing it (that is, there is no need for “infection”).

Therefore, we know that a recognizable display of emotion can be achieved without either self-expression or emotional contagion. Something can look happy or sad without being happy or sad. (For this reason, art’s expressive properties are often classified as aesthetic properties; see Chapter 4.) Therefore, in the same way that the dog’s face can be said to display sadness and not any other emotion, a drawing or painting of a human face can, too. And a good artist can capture sadness without expressing any of their own sadness, and without making the audience feel sad, either. Consider the painting The Last of England (see figure 3.6).

In this painting, Ford Madox Brown creates a scene in which emigrants who are sailing away to live in Australia are getting their final look at the English coast before the ship heads out to sea. The man and woman look unhappy, especially the man. For the man, Brown did a self-portrait. His wife posed for the woman. The painting took more than two years to complete. It is unlikely that the two of them were actually unhappy each and every time Brown worked on the portraits of the two faces. After all, people can make themselves look sad when they are not sad, so that the face displays the emotion of sadness without being a genuine expression of sadness. In fact, Brown was trying to capture an emotion he witnessed in a good friend who had financial problems and who emigrated to Australia in 1852. Art historians note that Brown was thinking of emigrating when he started the painting. (He did not emigrate.) So perhaps Brown is expressing his own emotion. But it is just as likely that he is capturing his friend’s emotion, instead. In that case, the emotion is something Brown is imagining while creating the image. But that is hardly the idea that Tolstoy was supporting when demanding “the sincerity of the artist.”

What matters is that Brown knew what to do to create an image that would convey the sadness of emigrants. Show Brown’s painting to someone without explaining the context or theme of emigration, and ask, “What is the feeling communicated by this picture?” Almost certainly, the answer will be “sadness” or “unhappiness” or perhaps even “misery.” That is what Brown wanted to capture, and he did. Since almost everyone will recognize the very same thing, it is plausible to say that the picture objectively displays sadness. There is no need for viewers to consult their own subjective feelings to arrive at the answer. For this reason, T.S. Eliot proposes that expressive art succeeds when it provides an objective correlative of an emotional state that the artist wants to portray. (See Section 3.4.)

At this point, it is useful to look at Brown’s painting and to distinguish two different questions.

- Does the painting require sincere self-expression in order for it to be art?

- Would Brown’s sincere self-expression make this painting more valuable as an artwork?

Tolstoy answers “yes” to question (1). If art historians could provide solid evidence that Brown was insincere, Tolstoy would conclude that this “so-called” art it is not really art at all.

Since it is obvious to most people that The Last of England is art even if there’s no self expression involved in it, most people will be more interested in question (2) than question (1), and will remove self-expression from the general definition of art.

T.S. Eliot famously argues that the answer to question (2) is also negative. He offers a thought experiment: suppose the character of Hamlet in William Shakespeare’s Hamlet involves self-expression on the part of the author. That might explain why the play is written in the manner it is. However, that would not be a reason to value the play more highly. Eliot joins with many other literary critics in thinking that this play fails to do what Brown’s The Last of England does so well. It fails to communicate any clear, objective correlative of the main character’s emotions. Furthermore, Eliot continues, the play’s lack of clarity concerning the character’s emotional state is compatible with its being a case of self-expression. Therefore, self-expression is not something that makes an artwork more valuable simply by its presence. The next section looks at Eliot’s position in greater detail.

3.4. Eliot and the Objective Correlative

T.S. Eliot was one of the most famous poets of the twentieth century. (He also had an accidental career as author of a popular Broadway musical when some of his poems were set to music as the words for the the musical Cats.) In addition to being a poet, he earned a Ph.D. in philosophy from Harvard University and was an influential literary critic.

Although Eliot supports the modern view that art is fundamentally concerned with emotional expression, he breaks from many other expression theorists by saying that art is not self-expression. The process of creating art always transforms what is being expressed. If it didn’t, it wouldn’t be art. An artist who explores emotion might begin with their own emotions, but then they create some independent thing out in the world that can be shared with other people. Emotions are subjective experiences, but artworks have to objectify emotion in order to share it. Therefore, what the artist shares with the audience — a poem, a painting, a gallery installation — is a substitute object that conveys something about emotion. An artwork might be inspired by the artist’s own life, but emotions are subjective and can only be understood by others by being expressed externally (and, hence, not the artist’s own emotion any longer). What is subjective must be rendered objective.

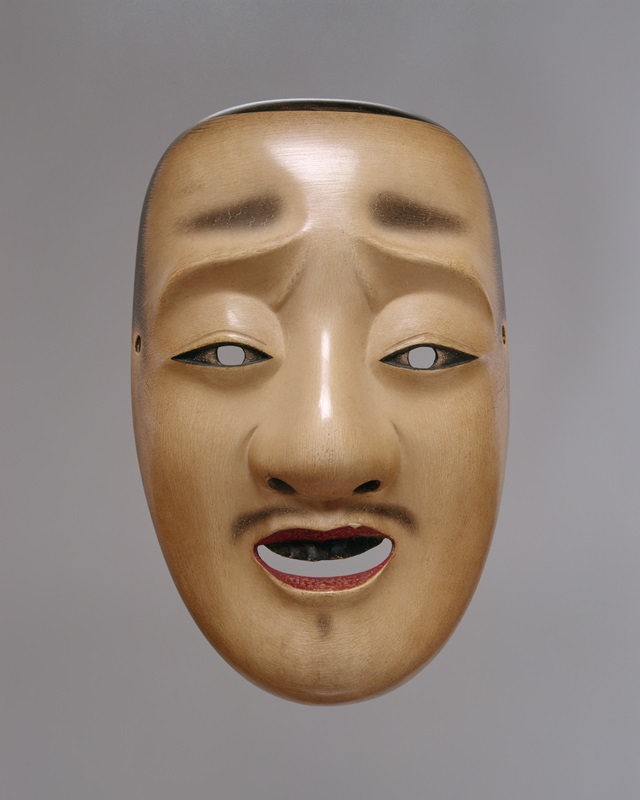

For Eliot, the artist creates a symbol that communicates one or more emotional responses. The work of art is the objective correlative (parallel) of the subjective experience. The trick is to find a combination of understandable things or events that will suggest a specific emotional state. Artistic creativity is the process of finding a clear symbol for a particular emotional experience.

To put it simply: if the external objectification of emotion did not differ from the emotion, no one could ever fake an emotion to others. An emotion is not the same as its externalization. An actor portraying Hamlet’s grief upon learning of the death of Ophelia doesn’t have to experience real grief in order to portray grief. What matters is that Shakespeare wrote a scene that can show us what grief is like. (Certainly, proponents of “method acting” think that actors who draw upon their own personal memories will give a more convincing performance, but it does not follow that this method is the only way to give a convincing performance.)

Here is another example, but concerning music. There is a portion of Gustav Mahler’s 5th symphony called the adagietto movement, and it was written as an expression of his love for his wife, Alma. In order to convey love, Mahler had to invent a sequence of sounds that would convey intensity and passion. The result is something that we audibly experience. We can listen to the piece of music. And we can continue to experience this music long after Gustav and Alma have died. It continues to exist, so it is something separate from their love. Nonetheless, many people who are familiar with European music regard it as an unusually expressive representation of love. Since almost no one today cares about the specifics of the relationship that inspired it, its expressive success is independent of the relationship that inspired it. In other words, Mahler found a combination of sounds that are in some manner parallel to, but independent of, his emotions, and at that point the fact that it was inspired by his feelings became irrelevant. This is what Eliot means when he says that a successful work of art will be an “objective correlative” of whatever the artist is trying to covey to the audience.

Consider Eliot’s own poetry. Here is a passage from one of his most radical poems, The Wasteland, from 1922. Take note that the passage begins with two lines in quotation marks.

“You gave me hyacinths first a year ago;

The poem is constantly changing voices, so readers must monitor it for changes of narrator or speaker. In this passage, a woman speaks about an event from a year earlier, and then someone else, hearing her words, thinks about their significance. As with Mahler’s 5th symphony adagietto, there is a bit of autobiography here. Eliot is drawing on an event when he was at Harvard and visited a Hyacinth garden with a woman he became close to. (They met due to their mutual interest in literature when they performed together in a play based on Jane Austen’s novel Emma.) The short passage quoted here contrasts the woman’s recollection of holding flowers with the narrator’s emotional response to the same event. The poem expresses the narrator’s confusion and sense of unreality at that time.

Did the poet actually experience this emotional state, and if he did so, was it in relation to this event? There is reason to think that Eliot is actually combining events that happened ten years apart in his life, involving two different women. The reaction (“I was neither/Living nor dead”) is more likely to be inspired by his emotional difficulties after he left the U.S., moved to England, and married someone else, only to discover that his wife was suffering from serious mental issues. If that is right, it illustrates Eliot’s point. The task of the artist is not to tell us some truth about the artist. The artist takes events from the artist’s emotional life and creates something original, something that will exist apart from the artist and that will clearly convey an emotional state.

How Shakespeare ruined Hamlet

Eliot’s position is most clearly presented in his famous essay on Shakespeare’s longest play, Hamlet. Going against the general view that Hamlet is a great play, Eliot endorses the minority view, which is that the play is a poorly constructed mess that makes little sense. Eliot starts by reminding us that most people in the 17th and 18th centuries thought that Hamlet was a poor play, and Eliot wants modern audiences to reconsider its recent positive reputation.

Like most of Shakespeare’s plays, Hamlet was adapted from the work of earlier writers. In itself, that is not the issue. The movie The Half of It (2020) is adapted from a 19th-cenutry play, Cyrano de Bergerac. As a queer updating, it forcefully confronts heteronormativity, that is, it confronts the cultural assumption that heterosexuality is the romantic norm. No one thinks its borrowings from another artwork are a defect, because the movie succeeds in its own right. Eliot is not bothered by the practice of borrowing from other authors, provided the artist makes good use of what is borrowed. In fact, The Wasteland is full of such borrowings. Eliot is bothered by Shakespeare’s inability to create a forceful, meaningful piece of theater when adapting the work of others. Shakespeare added a bunch of new subplots and plot twists that ended up confusing whatever he thought he was showing us.

Eliot suggests that the situation has a degree of irony. Many artists engage in self-expression, and perhaps Shakespeare was using himself as the model for the lead character. And perhaps this is why Shakespeare’s play fails. Self-expression only works if the artist attains self-understanding. The play lacks emotional clarity because the character of Hamlet lacks it. So, if the play is self-expression on Shakespeare’s part (“the supposed identity of Hamlet with his author”), what it reveals is that Shakespeare was an emotionally confused person who couldn’t share his emotions except in a confused way. Ironically, then, the play might be a successful objective correlative for Shakespeare’s emotional life when he wrote it! However, that doesn’t make it any better as a piece of theater or literature, which shows that self-expression is not intrinsically desirable. If the character of Hamlet is crafted through self-expression, then self-expression has made it a defective play. The play would be better if it provided an objective correlative that could be successfully integrated into the plot. And that is just what Eliot finds in Shakespeare’s source material: the source material concentrates on anger and revenge.

In summary, Eliot is not saying that it was mistake for Shakespeare to write the play by adapting the work of other writers. In another essay that Eliot wrote around the same time, he famously said, “Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal; bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better.” Every artist borrows from other artists. That’s simply how art works. The difference between good artists and bad ones is that the good ones “make it into something better.” Shakespeare failed to do this with the material he appropriated for Hamlet.

Excerpt from T.S. Eliot, “Hamlet and His Problems” (1920)

Few critics have even admitted that Hamlet the play is the primary problem, and Hamlet the character only secondary. …

Two recent writers, Mr. J. M. Robertson and Professor Stoll of the University of Minnesota, have issued small books which can be praised for moving in the other direction. Mr. Stoll performs a service in recalling to our attention the labours of the critics of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, observing that

they knew less about psychology than more recent Hamlet critics, but they were nearer in spirit to Shakespeareʹs art; and as they insisted on the importance of the effect of the whole rather than on the importance of the leading character, they were nearer, in their old‐fashioned way, to the secret of dramatic art in general.

[Considered as a] work of art, the work of art cannot be interpreted; there is nothing to interpret; we can only criticize it according to standards, in comparison to other works of art; and for ʺinterpretationʺ the chief task is the presentation of relevant historical facts which the reader is not assumed to know. Mr. Robertson points out, very pertinently, how critics have failed in their ʺinterpretationʺ of Hamlet by ignoring what ought to be very obvious: that Hamlet is a stratification, that it represents the efforts of a series of men, each making what he could out of the work of his predecessors. The Hamlet of Shakespeare will appear to us very differently if, instead of treating the whole action of the play as due to Shakespeareʹs design, we perceive his Hamlet to be superposed upon much cruder material which persists even in the final form.

We know that there was an older play by Thomas Kyd, that extraordinary dramatic (if not poetic) genius who was in all probability the author of two plays so dissimilar as The Spanish Tragedy and Arden of Feversham; and what this play was like we can guess from three clues: from The Spanish Tragedy itself, from the tale of Belleforest upon which Kydʹs Hamlet must have been based, and from a version acted in Germany in Shakespeareʹs lifetime which bears strong evidence of having been adapted from the earlier, not from the later, play. From these three sources it is clear that in the earlier play the motive was a revenge‐motive simply; that the action or delay is caused, as in The Spanish Tragedy, solely by the difficulty of assassinating a monarch surrounded by guards; and that the ʺmadnessʺ of Hamlet was feigned in order to escape suspicion, and successfully. In the final play of Shakespeare, on the other hand, there is a motive which is more important than that of revenge, and which explicitly ʺbluntsʺ the latter; the delay in revenge is unexplained on grounds of necessity or expediency; and the effect of the ʺmadnessʺ is not to lull but to arouse the kingʹs suspicion. The alteration is not complete enough, however, to be convincing. Furthermore, there are verbal parallels so close to The Spanish Tragedy as to leave no doubt that in places Shakespeare was merely revising the text of Kyd. And finally there are unexplained scenes—the Polonius‐Laertes and the Polonius‐Reynaldo scenes—for which there is little excuse; these scenes are not in the verse style of Kyd, and not beyond doubt in the style of Shakespeare. These Mr. Robertson believes to be scenes in the original play of Kyd reworked by a third hand, perhaps Chapman, before Shakespeare touched the play. And he concludes, with very strong show of reason, that the original play of Kyd was, like certain other revenge plays, in two parts of five acts each. The upshot of Mr. Robertsonʹs examination is, we believe, irrefragable: that Shakespeareʹs Hamlet, so far as it is Shakespeareʹs, is a play dealing with the effect of a motherʹs guilt upon her son, and that Shakespeare was unable to impose this motive successfully upon the ʺintractableʺ material of the old play.

Of the intractability there can be no doubt. So far from being Shakespeareʹs masterpiece, the play is most certainly an artistic failure. In several ways the play is puzzling, and disquieting as is none of the others. Of all the plays it is the longest and is possibly the one on which Shakespeare spent most pains; and yet he has left in it superfluous and inconsistent scenes which even hasty revision should have noticed. The versification is variable. Lines like

Look, the morn, in russet mantle clad, Walks oʹer the dew of yon high eastern hill

[Hamlet, Act 1, scene 1]

are of the Shakespeare of Romeo and Juliet. The lines in Act v. sc. ii.,

Sir, in my heart there was a kind of fighting

That would not let me sleep…

Up from my cabin,

My sea‐gown scarfʹd about me, in the dark

Gropʹd I to find out them: had my desire;

Fingerʹd their packet;

are of his quite mature. Both workmanship and thought are in an unstable condition. We are surely justified in attributing the play, with that other profoundly interesting play of ʺintractableʺ material and astonishing versification, Measure for Measure, to a period of crisis, after which follow the tragic successes which culminate in Coriolanus. Coriolanus may be not as ʺinterestingʺ as Hamlet, but it is, with Antony and Cleopatra, Shakespeareʹs most assured artistic success. And probably more people have thought Hamlet a work of art because they found it interesting, than have found it interesting because it is a work of art. It is the Mona Lisa of literature.

The grounds of Hamletʹs failure are not immediately obvious. Mr. Robertson is undoubtedly correct in concluding that the essential emotion of the play is the feeling of a son towards a guilty mother:

[Hamletʹs] tone is that of one who has suffered tortures on the score of his motherʹs degradation…. The guilt of a mother is an almost intolerable motive for drama, but it had to be maintained and emphasized to supply a psychological solution, or rather a hint of one.

This, however, is by no means the whole story. It is not merely the ʺguilt of a motherʺ that cannot be handled as Shakespeare handled the suspicion of Othello, the infatuation of Antony, or the pride of Coriolanus. The subject might conceivably have expanded into a tragedy like these, intelligible, self‐complete, in the sunlight. Hamlet, like the sonnets, is full of some stuff that the writer could not drag to light, contemplate, or manipulate into art. And when we search for this feeling, we find it, as in the sonnets, very difficult to localize. You cannot point to it in the speeches; indeed, if you examine the two famous soliloquies you see the versification of Shakespeare, but a content which might be claimed by another, perhaps by the author of the Revenge of Bussy dʹ Ambois, Act v. sc. i. We find Shakespeareʹs Hamlet not in the action, not in any quotations that we might select, so much as in an unmistakable tone which is unmistakably not in the earlier play.

The only way of expressing emotion in the form of art is by finding an ʺobjective correlativeʺ; in other words, a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that particular emotion; such that when the external facts, which must terminate in sensory experience, are given, the emotion is immediately evoked. If you examine any of Shakespeareʹs more successful tragedies, you will find this exact equivalence; you will find that the state of mind of Lady Macbeth walking in her sleep has been communicated to you by a skilful accumulation of imagined sensory impressions; the words of Macbeth on hearing of his wifeʹs death strike us as if, given the sequence of events, these words were automatically released by the last event in the series. The artistic ʺinevitabilityʺ lies in this complete adequacy of the external to the emotion; and this is precisely what is deficient in Hamlet. Hamlet (the man) is dominated by an emotion which is inexpressible, because it is in excess of the facts as they appear. And the supposed identity of Hamlet with his author is genuine to this point: that Hamletʹs bafflement at the absence of objective equivalent to his feelings is a prolongation of the bafflement of his creator in the face of his artistic problem. Hamlet is up against the difficulty that his disgust is occasioned by his mother, but that his mother is not an adequate equivalent for it; his disgust envelops and exceeds her. It is thus a feeling which he cannot understand; he cannot objectify it, and it therefore remains to poison life and obstruct action. None of the possible actions can satisfy it; and nothing that Shakespeare can do with the plot can express Hamlet for him. And it must be noticed that the very nature of the [heart] of the problem precludes objective equivalence. To have heightened the criminality of Gertrude would have been to provide the formula for a totally different emotion in Hamlet; it is just because her character is so negative and insignificant that she arouses in Hamlet the feeling which she is incapable of representing.

The ʺmadnessʺ of Hamlet lay to Shakespeareʹs hand; in the earlier play a simple ruse, and to the end, we may presume, understood as a ruse by the audience. For Shakespeare it is less than madness and more than feigned. The levity of Hamlet, his repetition of phrase, his puns, are not part of a deliberate plan of dissimulation, but a form of emotional relief. In the character Hamlet it is the buffoonery of an emotion which can find no outlet in action; in the dramatist it is the buffoonery of an emotion which he cannot express in art. The intense feeling, ecstatic or terrible, without an object or exceeding its object, is something which every person of sensibility has known; it is doubtless a study to pathologists. It often occurs in adolescence: the ordinary person puts these feelings to sleep, or trims down his feeling to fit the business world; the artist keeps it alive by his ability to intensify the world to his emotions. The Hamlet of Laforgue is an adolescent; the Hamlet of Shakespeare is not, he has not that explanation and excuse. We must simply admit that here Shakespeare tackled a problem which proved too much for him. Why he attempted it at all is an insoluble puzzle; under compulsion of what experience he attempted to express the inexpressibly horrible, we cannot ever know. We need a great many facts in his biography; and we should like to know whether, and when, and after or at the same time as what personal experience, he read Montaigne, II. xii., Apologie de Raimond Sebond. We should have, finally, to know something which is by hypothesis unknowable, for we assume it to be an experience which, in the manner indicated, exceeded the facts. We should have to understand things which Shakespeare did not understand himself.