4 The Aesthetic Dimension

Theodore Gracyk

Key Takeaways for the Aesthetic Dimension

Topic: Do the arts have a special kind of value, aesthetic value?

Beauty, an aesthetic property, was among the original requirements for fine art

Other aesthetic properties became accepted, as well

Instrumental music is offered as a case of art that has no value other than aesthetic value

Aesthetic properties are generally associated with artistic design or form

Focus on abstraction in visual art has been used as evidence that aesthetic value is the only common feature in valuable art

Psychologists have hypothesized that special mental processes are required to experience aesthetic properties

If true, artistic failure can be traced to an artist’s failure to address these processes as they function in the audience

4.1 Introduction to Chapter 4

Philosophy of art is often called aesthetics. Why is that? The label “aesthetic” comes from the Greek word for sensory perception. We look at paintings. We listen to music. Furthermore, the fine arts were the original focus of philosophy of art, and the “fine” of “fine art” is a reference to beauty, which is a perceptual feature of art. When the English created the the phrase “fine art” in the 18th century, they were translating the French phrase, beaux arts (literally, “beautiful arts”). Therefore, modern philosophy of art was launched with an embedded assumption that philosophizing about art requires philosophizing about beauty. And because of this focus on beauty, philosophy of art required a discussion of aesthetics.

The aesthetic dimension of a thing is how it is agreeable or disagreeable to human perception. An aesthetic account of art is one that says that the presentation of aesthetic properties is either the primary aim of art, or one among several equally important aims. In other words, visual art is valuable because people enjoy looking at it. Music is valuable because people enjoy hearing it. (Leo Tolstoy attacks this view in the excerpt provided in Chapter 3 of this book.)

Generally, the more powerful the aesthetic impact, the better the work of art. As such, successful works of art are said to be aesthetically valuable. As in the definition of art provided by Charles Batteux in 1746 (see Chapter 1), aesthetic theories of art have historically emphasized beauty. One important difference between modern art and earlier art is that modern artists feel free to explore a wider range of aesthetic effects.

The most common view is that an aesthetic property is a feature that exists only in perception. Some things taste bitter. Some music sounds harsh. Bitterness and harshness are features that arise in the human response to what is perceived. But what is perceived varies from person to person. Using beauty as his primary example of an aesthetic feature, David Hume drew the obvious conclusion:

Beauty is no quality in things themselves: It exists merely in the mind which contemplates them; and each mind perceives a different beauty. One person may even perceive deformity, where another is sensible of beauty; and every individual ought to acquiesce in his own sentiment, without pretending to regulate those of others. To seek the real beauty, or real deformity, is as fruitless an enquiry, as to pretend to ascertain the real sweet or real bitter. (Hume, “Of the Standard of Taste,” 1757).

This idea is often captured by the expression, “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder.” Unfortunately, this is often taken to mean that aesthetic features are entirely subjective. Hume and many other philosophers point out that aesthetic features nonetheless have some level of objectivity. It wouldn’t make sense for anyone to encourage you to look at the beautiful sunset unless they expect you to see its beauty, too.

However, beauty is merely one of many aesthetic features. Consider cuteness. Some things look cute. (See figure 4.1.) So, cuteness is also an aesthetic property. (In the context of philosophy, a “property” is feature or characteristic of something.) Visual cuteness is a feature that only exists in the visual field of someone looking at it. Yet it is something that we point out to others and expect them to recognize, as well. Cuteness is not confined to vision. Some voices and sounds are cute, as well.

Some aesthetic properties only emerge gradually, over time. Unlike cuteness, these features cannot be perceived at a glance. This is most common in the narrative arts. When a film review says that The Crow (2024) is a “disaster” because it is “incoherently plotted and sloppily made,” that is an aesthetic evaluation. Clearly, the reviewer assumes that others will experience the incoherence and sloppiness. Thus, aesthetics may be grounded in subjective response, but many philosophers suggest that it occupies a middle ground between what is objective and what is merely subjective. The aesthetic dimension is located in the realm of inter-subjective responses: these responses vary widely, yet they are clearly rooted in features of the external world.

The experience of color is another inter-subjective response: not everyone sees the same colors, and some people cannot see some colors at all, yet there is enough agreement in response among enough people that sentences such as “Stop signs are red and white” count as true statements. Similarly, sentences such as “Puppies are cuter than frogs” are true even if some people don’t share that response.

Historically, beauty has received more attention than other aesthetic properties. In the past, the other important ones were the picturesque (a pretty landscape) and the sublime (basically, whatever is awe-inspiring, including the subcategory of terror). The term “picturesque” was in common use in the 19th century but fell out of favor starting at the beginning of the 20th century. Today, “sublime” is often used interchangeably with “beauty.” In the past, however, they were sharply distinguished. A hundred years ago, the awe-inspiring wreckage left in the path of a hurricane would be categorized as sublime, meaning that it was not beautiful. Endless stretches of barren desert sands are sublime, but few find them beautiful.

In the twentieth century, beauty became less important to artists. Philosophers responded to this trend by recognizing that philosophy of art had neglected the diversity of aesthetic properties. In essays published between 1959 and and 1968, Frank Sibley stressed that we have words for many different aesthetic properties. As a sample, he noted that we employ “aesthetic concepts” when referring to perceived objects as graceful, delicate, dainty, elegant, garish, balanced, unified, serene, somber, dynamic, powerful, vivid, delicate, moving, lifeless, trite, sentimental, or tragic. Another reason to expand our thinking beyond beauty is that it is a positive feature. However, many aesthetic features are negative, or unattractive, as when a painting is sloppy, unbalanced and garish, or a story is bad because it is incoherent. And there are aesthetic properties that are important in other cultures that have no equivalent name in English. The Japanese concept of wabi sabi is a prime example. Much of the richness of art and culture stems from the wide range of aesthetic properties that humans can deploy in various media and crafts.

As noted in the opening paragraph of this chapter, there is a long-standing assumption that the presentation of attractive aesthetic properties is a fundamental goal of art. Return again to Chapter 1 and Batteux’s definition of the fine arts. Unfortunately, his formula for art is often misunderstood. He says that the fine arts provide pleasure through the imitation of beautiful nature. However, he does not mean that art involves finding beautiful things in nature and making images of those things. He means that art (anything hand-crafted based on a teachable skill) becomes fine art when it satisfies two requirements: (1) there is an element of representation (imitation) and (2) the artwork possesses beauty. The reference to “nature” means that the artist tries to capture the essence of what is represented (its basic nature) rather than superficial aspects.

Something very similar was later expressed by the poet John Keats: “Beauty is truth, truth beauty.” They both think that an artist must imaginatively explore things in order to arrive at their essential nature, that is, their essential or ideal features. Once this is worked out, the result will be something true and beautiful. As Batteux says, even something that is ugly in real life makes for beautiful art. The same point is made by Immanuel Kant.

In some ways, then, this chapter is simply a deeper exploration of Batteux and Kant, both of whom endorsed an aesthetic account of art in which beauty is one of the requirements of fine art. Modern aesthetic accounts move from the hypothesis that every work of art is beautiful to the hypothesis that every work of art is aesthetically rewarding in some manner.

Expression of emotion is a complicating case. When emotions take a perceptible form in an artwork, these expressive features are generally counted among aesthetic properties. In this way, expression theories are sometimes classified as a subset of aesthetic accounts of art.

Let us return to the point that we have labels for many different aesthetic properties. Here are some more features of things that are aesthetic properties. In this list, the words in bold type are making reference to aesthetic properties:

- The story was about an astronaut trying to get home, and it was suspenseful.

- The story was about an astronaut trying to get home, but it was confusing.

- The story was about an astronaut trying to get home, and it was scary.

- The movie was short, but it drags.

- The movie is about the Easter Bunny, and it was creepy.

- The haunted house was kitschy instead of eerie.

- The singer ruined the sweet song with her screechy delivery.

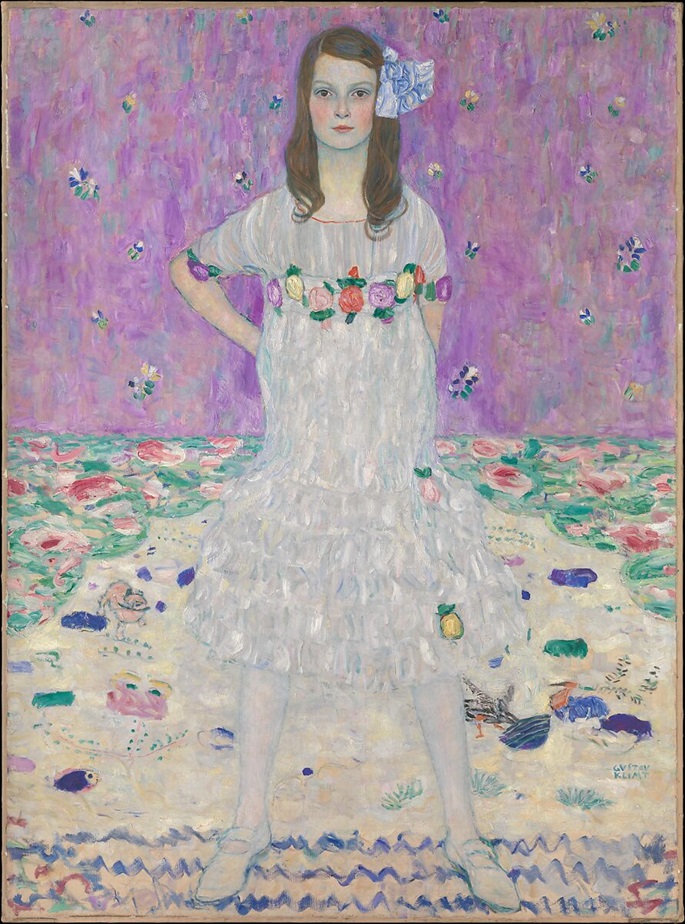

- The use of color and the accumulation of simple elements makes Gustav Klimt’s work complex, vibrant, and joyful. (See figure4.2.)

In summary, aesthetic theories of art say that artistic creativity and value are intertwined with aesthetic creativity and value. There are extreme versions of this doctrine. Many philosophers and art critics have held that artistic value is identical with an artwork’s aesthetic value. The most radical version says that aesthetic/artistic value excludes the expression of emotion, which distracts us from attending to aesthetic properties. Art is best when it avoids expression of emotion. This chapter presents two versions of this idea. The first is Eduard Hanslick’s argument in Section 4.2 that instrumental music has no ability to represent other things, and it does not present any genuine expressive properties. Therefore, good instrumental music is of value only for its non-expressive aesthetic dimension. A second theory is Clive Bell’s argument in Section 4.3 that abstraction in visual art shows that the true purpose of art is the display of aesthetically powerful abstractions. Where Bell’s theory suggests that our aesthetic response is beyond anyone’s personal control, Section 4.4 presents Edward Bullough’s account of how specific artistic decisions can encourage and discourage aesthetic appreciation.

4.2 Hanslick on Musical Beauty

This section focuses on music, especially instrumental music (that is, music without any singing or words). Batteux proposed that instrumental music is art because it is the primary way we can “picture” or represent emotions or feelings. Thus, instrumental music satisfies his twin requirements of representation and beauty. This view of music and emotion is probably the most common view of the value of music.

However, there has also been a long-standing tradition of denying that instrumental music can represent the emotions. Ironically, one of the most influential denials of the expressive power of music came from Eduard Hanslick, a famous music critic who became Europe’s first academic musicologist. He defended the view that the best instrumental music is pure form that exists solely to highlight aesthetic properties, especially beauty.

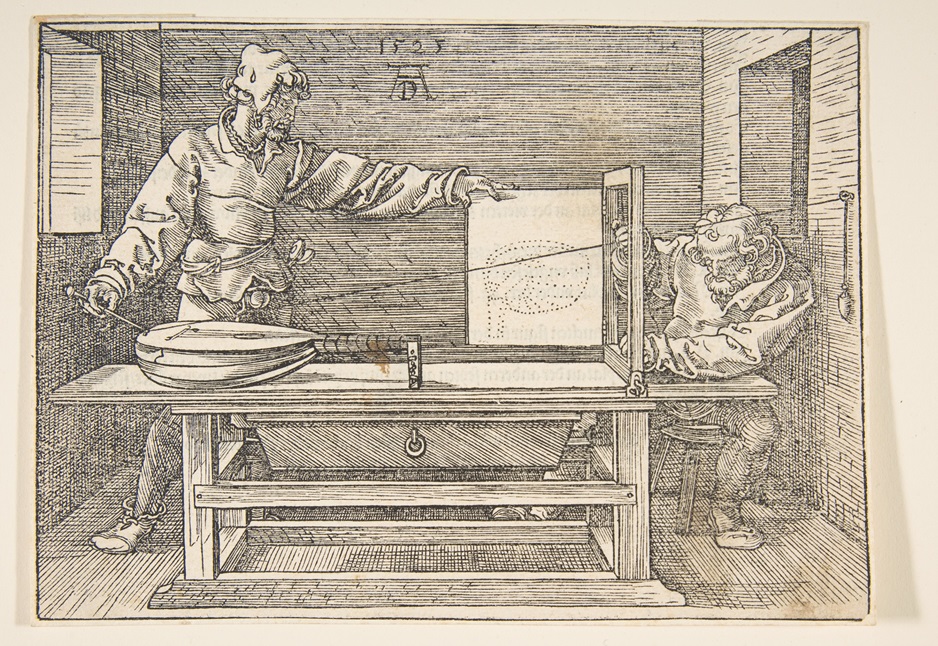

This issue became important in the 19th century because abstract visual art did not yet exist. Music seemed to be the one branch of art that did not meet the traditional requirement of representation. The growing recognition that music could be valuable for purely aesthetic reasons (for its aesthetic properties and nothing more) was a major touchstone of the “aesthetic movement” in 19th-century art. Walter Pater, an art critic who brought renewed attention to Renaissance art, famously claimed that “all art constantly aspires to the condition of music.” All art creates aesthetic properties by creating relationships among its various elements. With instrumental music, this can be the exclusive attraction of listening. In saying that other arts “aspire” to be like music, Pater means that great art always prioritizes aesthetic properties, creating an “abstract language” that sacrifices representational accuracy for the sake of aesthetic value. (There is more about abstraction below, in Section 4.3.)

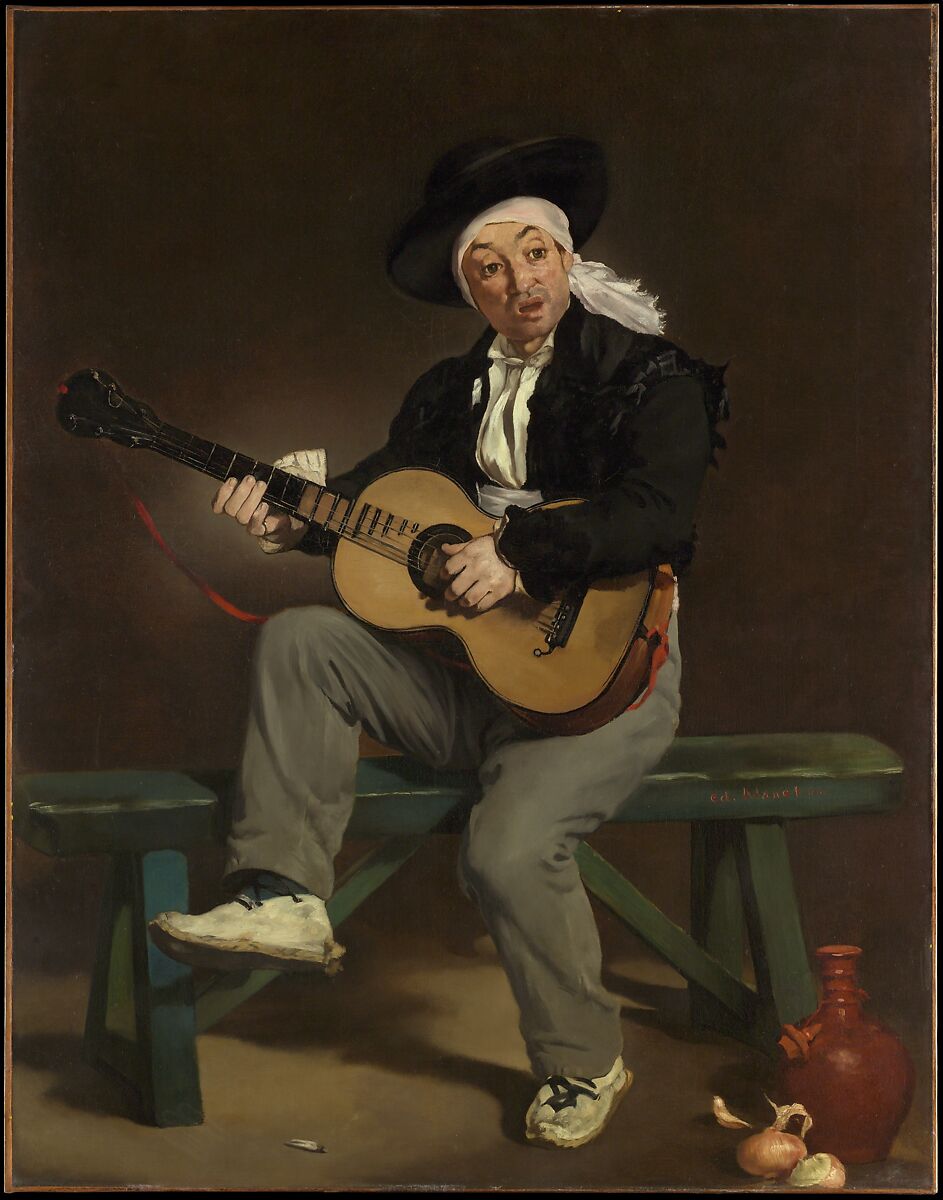

Exploring the parallel between music and visual art, a number of 19th-century painters moved in the direction of visual abstraction. A prime example is James McNeill Whistler, who reduced the representational element of his work to a bare minimum in order to prioritize form and color. He even took to naming some of his paintings with the names for musical genres, such as “nocturne.” (See figure 4.3.) This practice of using musical names was later adopted by the abstract painter Wassily Kandinsky. (See Section 4.3.) In his own lifetime, much of Whistler’s output was attacked by traditional art critics who were struck by aesthetic features that they saw as ruining the work. Whistler’s paintings were dismissed as sloppy, obscure, and reckless.

Whistler and Kandinsky had different goals in using musical terms in the names of their paintings. In Whistler’s case, the titles suggest that visual art should be judged by analogy with the doctrine of musical formalism. It is the thesis that music is basically the structuring of certain sounds into interesting patterns. Successful instrumental music is nothing but sound that is structured to create aesthetic properties, especially beauty. From this perspective, songs are an impure, mixed-media form of art, for they depend on language for part of their effect. In contrast to Whistler, Kandinsky was drawing on the traditional doctrine that music’s special power is the representation of emotion. By moving into abstraction, Kandinsky thought he could convey purified, universal emotion. So, he was not a pure formalist.

Hanslick defended musical formalism in a highly influential book: On the Musically Beautiful (1854). The book argues that the value of music has nothing to do with the expression of emotion. Put simply, Hanslick argues that the expression of emotion cannot be the aim of composers and cannot be what makes instrumental music valuable for the simple reason that it cannot be done. Instrumental music cannot represent emotion. At best, music conveys some of the energy associated with various emotions.

This doesn’t mean that “pure” music lacks emotional power. Beauty and other aesthetic properties can be emotionally powerful, so music can move us even if it does not itself express emotion. (Sixty years later, Clive Bell would make the same argument about visual art.)

Turning now to the text of On the Musically Beautiful, Hanslick’s argument proceeds on two fronts. On the one hand, he directly attacks the claims made in expression theories as applied to music. On the other hand, he describes an alternative theory of the aesthetic value of music. To follow the arguments that attack expression theories, keep in mind the difference between an infection or arousal theory (like Leo Tolstoy’s) and a theory that says art displays emotions rather than arousing them (like T.S. Eliot’s). (These two theories of expression are covered in Chapter 3 of this textbook.) Hanslick first attacks the infection/arousal version, then afterwards turns his attention to display-of-emotion theories.

If music cannot display emotion, why do so many people believe that it can? Because, Hanslick observes, most music takes the form of song. When words are added, the music’s sense of energy and motion is given a representational focus. The resulting combination of words and music can be expressively clear and powerful. However, the very same music is often combined with different words. When this is done, the emotional expression of the music changes. Sometimes it changes radically. He offers the example of well-known music written by George Frideric Handel. Much of Handel’s Messiah consists of songs that he wrote earlier, with different words. By adding Bible verses to old melodies, Handel transformed erotic love songs into Christian devotion. However, these are radically different emotions! Therefore, Hanslick argues, the words and not the music must be what give a song its expressive specificity. By itself, music has no such specificity.

The Argument of Hanslick’s Chapter 1

In Chapter 1 of his book, Hanslick attacks theories like Tolstoy’s that say music communicates emotion by “exciting” or “arousing” it in listeners. Hanslick offers two basic arguments against this approach. First, he goes into the psychology of listening and argues that it just does not work that way. Next, he allows (for purpose of argument) that it does sometimes excite emotion, but then asks, so what if it does? The side effects you get from taking medicine might be equally notable, but they aren’t the purpose of taking the medicine. Some people might experience various emotions when listening to music, but these are basically a side issue.

Hanslick asks us to focus on what composers actually create when they compose. Overwhelmingly, they work with their imagination to come up with auditory designs. For a composer, the auditory design is what they find interesting. This is where they place their creative efforts. Likewise, when people listen to music, its primary effect is to stimulate their imaginations. (Basically, listeners keep anticipating what comes next, which requires imaginative projection.) If audience engagement depends on imaginative engagement, then this “pure act of listening” is more fundamental than emotional response. If there is an arousal of emotion, that’s just a side effect of the anticipations and expectations about what’s coming next in the musical design. Likewise, engagement with emotion is a side-project for some composers, especially songwriters, but there is no reason to think it motivates every musician.

Hanslick’s next argument is that we do not have a theory of art unless we have a theory about what is special about art. Even if emotions are “excited” by the experience of music, that doesn’t make music interesting or special. A newspaper story can do that, too, but it isn’t art. Furthermore, if we were to suppose that music is valuable because it transmits emotions, then most composers are bad at their work. Transmission of feeling through music is not uniform enough. Different listeners feel very different things in response to the same music. (Some listerners feel bored, and others irritated!) Finally, the emotional response is unstable. It is altered by texts and titles and it is perceived differently “according to our changing musical experiences” (that is, according to what other styles of music we know and the “circumstances” in which we hear it).

The Argument of Hanslick’s Chapter 2

Chapter 2 of Hanslick’s book examines expression theory of the kind defended by T.S. Eliot, where successful expression involves showing, illustrating, or somehow representing our emotional lives. This approach says that audience recognition is what matters, rather than how the audience feels in response.

Hanslick begins with the idea that the basic test of successful representation is the audience’s ability to recognize the content without being told what to look for. What would this be in the case of music? Music is dynamic, and so what it can illustrate is the interplay of dynamic forces. After all, many musicians have used the dynamics of music to represent things other than emotions, such as thunderstorms and battles. Arthur Honegger’s Pacific 231 presents a steam train gathering speed. Claude Debussy’s La Mer represents the ocean at different times of day. (One passage is interpreted as a mermaid rising from beneath the water, singing.) Unless we receive external guidance, listeners have no reason to think they’re hearing a representation of emotion instead of weather or the ocean waves.

Hanslick asks what would have to be added to the dynamics of motion in order to clearly signify the dynamics of emotion. He adopts an idea endorsed by many psychologists, which is that emotions are distinguished from one another by a cognitive (conceptual) component. In order to have a recognizable emotion, a person needs to direct their feelings at some particular object or event. An unfocused emotion isn’t a specific emotion. Why? Because the same felt dynamic occurs for more than one emotion, and we can only decide which one we’re feeling by determining what thing or event has activated our emotional response. Furthermore, a single emotion can take many different dynamic forms. Hanslick offers love as an example. Sometimes it feels one way, sometimes another. At one moment, someone may feel protective of the one they love. Another time, jealous. These are both expressions of love, yet they feel very different. What unifies them under the category of love is the relationship to the person who activates the feeling. Separated from events around us, a feeling doesn’t count as a “definite,” identifiable emotion. Therefore, musical dynamics of instrumental music cannot represent definite feelings unless the music also communicates identifiable subject matter. But it cannot: that has to be supplied extra-musically, with a title or program notes or lyrics added to the music.

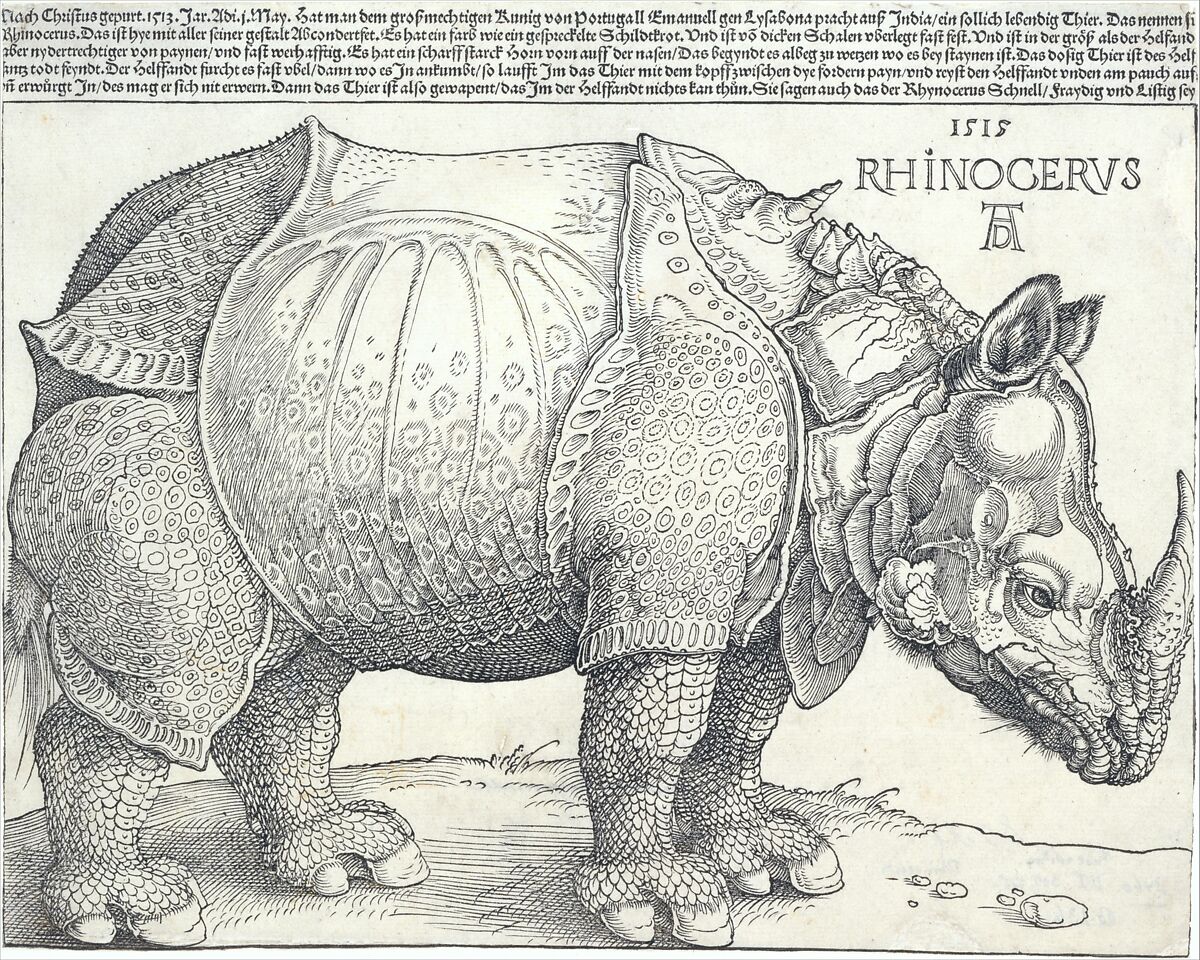

The point here is that if a representation is not routinely recognized as the representation of one thing rather than another, it isn’t a representation. Look again at the picture of the cute cat. (See figure 4.1.) If no one could see a cat in the picture simply by looking at the picture, or if viewers were divided and some see a cat, some see a house, and some see an airplane, then it wouldn’t count as a representation of a cat. But that’s the state of affairs we have when people try to name the emotion supposedly expressed in instrumental music: there is nothing definite about it. Therefore, it isn’t representation. And if we cannot pin down the non-emotional content, we cannot pin down the expressive content, either.

Finally, Hanslick discusses an objection to his own favored theory, which is that we appreciate and value music as pure sonic form. Songs obviously express very definite emotions. So, music does express feelings. Granted, it might not be self-expression in all cases, but it’s there.

Hanslick has two replies to arguments that appeal to the emotional power of songs. First, we already know that words express emotions. Poems do it all the time, and song lyrics are poems. Adding words to music gives the combination a definite expression, but it’s the words that do all the work here. So songs don’t support the idea that music, by itself, conveys feelings, Second, the same music is often given different lyrics. He offers examples of Mozart and Handel where two sets of words express completely unrelated emotions, yet they work equally well with the music. Hanslick thinks that this confirms that the music isn’t the part of the song that expresses emotion.

Hanslick concludes that the value of music is creative display of dynamic designs. In this sense, it is all about sensations (what we perceive), rather than feelings (what it does to the nervous system).

Excerpts from Eduard Hanslick: On the Musically Beautiful

Translated by Gustav Cohen, amended by T. Gracyk

CHAPTER I

AESTHETICS AS FOUNDED ON FEELINGS

Music, we are told, cannot, like poetry, entertain the mind with definite conceptions; nor yet the eye, like sculpture and painting, with visible forms. Hence, it is argued, its object must be to work on the feelings. ʺMusic has to do with feelings.ʺ This expression, ʺhas to do,ʺ is highly characteristic of all works on musical aesthetics. But what the nature of the link is that connects music with the emotions, or certain pieces of music with certain emotions; by what laws of nature it is governed; what the canons of art are that determine its form—all these questions are left in complete darkness by the very people who have ʺto doʺ with them. Only when oneʹs eyes have become somewhat accustomed to this obscurity does it become manifest that the emotions play a double part in music, as currently understood.

On the one hand it is said that the aim and object of music is to excite emotions, i.e., pleasurable emotions; on the other hand, the emotions are said to be the subject matter which musical works are intended to illustrate.

Both propositions are alike in this: they are both false. …

[Hanslick offers a list of examples of the position he attacks:]

- Neidhardt: ʺThe ultimate aim of music is to rouse all the passions by means of sound and rhythm, rivaling the most eloquent oration.ʺ (Preface to Temperatur.) …

- J. Mosel defines music as ʺthe art of expressing certain emotions through the medium of systematically combined sounds.ʺ…

- C. F. Michaelis: ʺMusic … is the language of emotion,ʺ etc. (Concerning the Spirit of Music, 2nd essay, 1800, p. 29.) …

- J. J. Engel: ʺA symphony, a sonata, etc., must be the representation of some passion developed in a variety of forms.ʺ (A Study of Music. Malerei, 1780, p. 29.) …

- J. W. Boehm: ʺNot to the intellect do the sweet strains of music appeal, but to our emotional faculty only.ʺ (Analysis of the Beauty of Music, Vienna, 1830, p. 62.) …

- Fermo Bellini: ʺMusic is the art of expressing sentiments and passions through the medium of sound.ʺ (A Manual of Music, Milano, Ricordi, 1853.) …

In order to examine this relation critically we must, in the first place, scrupulously distinguish between the terms ʺfeelingʺ and ʺsensation,ʺ although in ordinary parlance no objection need be raised to their indiscriminate use.

ʺSensationʺ is the act of perceiving some sensible quality, such as a sound or a color, whereas ʺfeelingʺ is the consciousness of some psychical activity, i.e., a state of satisfaction or discomfort.

If I note (perceive) with my senses the odor or taste of some object, or its form, color, or sound, I call this state of consciousness ʺmy sensationʺ of these qualities; but if sadness, hope, cheerfulness, or hatred appreciably raise me above or depress me below the habitual level of mental activity, I am said to ʺfeel.ʺ

Musical beauty first of all, affects our senses. This, however, is not peculiar to the beautiful alone, but is common to all phenomena whatsoever. Sensation, the beginning and condition of all aesthetic enjoyment … All art aims, above all, at producing something beautiful which affects not our feelings but the [mental power] of pure contemplation, our imagination. A musical composition originates in the composerʹs imagination and is intended for the imagination of the listener. Our imagination, it is true, does not merely contemplate the beautiful, but contemplates it with intelligence—the object being, as it were, mentally inspected and criticized. Our judgment, however, is formed so rapidly that we are unconscious of the separate acts involved in the process, whence the delusion arises that what in reality depends upon a complex train of reasoning is merely an act of intuition. …

It is manifest, therefore, that the effect of music on the emotions does not possess the attributes of inevitableness, exclusiveness, and uniformity that a phenomenon from which aesthetic principles are to be deduced ought to have. …

Music may, undoubtedly, awaken feelings of great joy or intense sorrow; but might not the same or a still greater effect be produced by the news that we have won the first prize in the lottery, or by the dangerous illness of a friend? So long as we refuse to include lottery tickets among the symphonies, or medical bulletins among the overtures, we must refrain from treating the emotions as an aesthetic monopoly of music in general or a certain piece of music in particular. …

CHAPTER II

DOES MUSIC REPRESENT FEELINGS?

… Definite feelings and emotions are not capable of being embodied in music.

Our emotions have no isolated existence in the mind and cannot, therefore, be conveyed by an art which is incapable of representing the remaining series of mental states. They are, on the contrary, dependent on physiological and pathological conditions, on notions and judgments: in fact, on all the processes of human reasoning which so many conceive as antithetical to the emotions.

What, then, transforms an indefinite feeling into a definite one — into the feeling of longing, hope, or love? Is it the mere degree of intensity, the fluctuating rate of inner motion? Assuredly not. The latter may be the same in the case of dissimilar feelings or may, in the case of the same feeling, vary with the time and the person. Only by virtue of ideas and judgments — unconscious though we may be of them when our feelings run high — can an indefinite state of mind pass into a definite feeling.

The feeling of hope is inseparable from the conception of a happier state which is to come, and which we compare with the actual state. The feeling of sadness involves the notion of a past state of happiness. These are perfectly definite ideas or conceptions, and in default of them‐the apparatus of thought, as it were‐no feeling can be called ʺhopeʺ or ʺsadness,ʺ for through them alone can a feeling assume a definite character. Subtract the contribution of definite concepts and nothing remains but a vague sense of motion which at best could not rise above a general feeling of satisfaction or discomfort.

The feeling of love cannot be conceived apart from the image of the beloved being, or apart from the desire and the longing for the possession of the object of our affections. It is not the kind of psychical activity but the intellectual substratum, the subject underlying it, which constitutes it love. Dynamically speaking, love may be gentle or impetuous, buoyant or depressed, and yet it remains love. … A determinate feeling (a passion, an emotion) as such never exists without a definable meaning which can, of course, only be communicated through the medium of definite ideas. Now, since music as an ʺindefinite form of speechʺ is admittedly incapable of expressing definite ideas, is it not a psychologically unavoidable conclusion that it is likewise incapable of expressing definite emotions? For the definite character of an emotion rests entirely on the meaning involved in it. …

[If not definite emotions, what can music convey?] A certain class of ideas, however, is quite susceptible of being adequately expressed by means which unquestionably belong to the sphere of music proper. This class comprises all ideas that … are associated with audible changes of strength, motion, and ratio: the ideas of intensity waxing and diminishing; of motion hastening and lingering; of ingeniously complex and simple progression, etc. The aesthetic expression of music may be described by terms such as graceful, gentle, violent, vigorous, elegant, fresh‐all these ideas being expressible by corresponding modifications of sound. We may, therefore, use those adjectives as directly describing musical phenomena without thinking of the ethical meanings attaching to them in a psychological sense, and which, from the habit of associating ideas, we readily ascribe to the effect of the music, or even mistake for purely musical properties. …

What part of the feelings, then, can music represent, if not the subject involved in them?

Only their dynamic properties. It may reproduce the motion accompanying psychical action, according to its momentum: speed, slowness, strength, weakness, increasing and decreasing intensity. But motion is only one of the concomitants of feeling, not the feeling itself. It is a popular fallacy to suppose that the descriptive power of music is sufficiently qualified by saying that, although incapable of representing the subject of a feeling, it may represent the feeling itself — not the object of love, but the feeling of love. In reality, however, music can do neither. It cannot reproduce the feeling of love but only the element of motion; and this may occur in any other feeling just as well as in love, and in no case is it the distinctive feature. The term ʺloveʺ is as abstract as ʺvirtueʺ or ʺimmortality,ʺ and it is quite superfluous to assure us that music is unable to express abstract notions. No art can do this, for it is a matter of course that only definite and concrete ideas (those that have assumed a living form, as it were) can be incorporated by an art.ʹ But no instrumental composition can describe the ideas of love, wrath, or fear, since there is no causal nexus between these ideas and certain combinations of sound. Which of the elements inherent in these ideas, then, does music turn to account so effectually? Only the element of motion — in the wider sense, of course, according to which the increasing and decreasing force of a single note or chord is ʺmotionʺ also. This is the element which music has in common with our emotions and which, with creative power, it contrives to exhibit in an endless variety of forms and contrasts. …

Beyond the analogy of motion … music possesses no means for fulfilling its alleged mission.

VOCAL MUSIC

We have intentionally selected examples from instrumental music, for only what is true of the latter is true also of music as such. If we wish to decide the question whether music possesses the character of definiteness, what its nature and properties are, and what its limits and tendencies, no other than instrumental music can be taken into consideration. What instrumental music is unable to achieve lies also beyond the pale of music proper, for it alone is pure music. No matter whether we regard vocal music as superior to or more effective than instrumental music (an unscientific proceeding, by the way, which is generally the upshot of one‐sided dilettantism), we cannot help admitting that the term ʺmusic,ʺ in its true meaning, must exclude compositions in which words are set to music. In vocal or operatic music it is impossible to draw so nice a distinction between the effect of the music and that of the words … An inquiry into the subject of music must leave out even compositions with inscriptions, or so‐called program music. Its union with poetry, though enhancing the power of the music, does not widen its limits. …

Vocal music colors, as it were, the poetic [verbal] drawing. In the musical elements we were able to discover the most brilliant and delicate hues and an abundance of symbolic meanings. Music might sometimes help transform a second‐rate poem into a passionate effusion of the soul. However, it is not the music but the words which determine the subject of a vocal composition. Not the coloring but the drawing renders the represented subject intelligible. We appeal to the listenerʹs faculty of abstraction, and beg the listener to think, in a purely musical sense, of some dramatically effective melody apart from the context. A melody, for instance, which impresses us as highly dramatic and which is intended to represent the feeling of rage can express this state of mind in no other way than by quick and impetuous motion. Words expressing passionate love, though diametrically opposed in meaning, might, therefore, be suitably rendered by the same melody …

Has the reader ever heard the allegro fugato from the overture to [Mozart’s] The Magic Flute changed into a vocal quartet of quarreling Jewish peddlers? Mozartʹs music, though not altered in the smallest degree, fits the low text appallingly well, and the enjoyment we derive from the gravity of the music in the opera can be no heartier than our laugh at the farcical humor of the parody. We might quote numberless instances of the plastic character of every musical theme and every human emotion. The feeling of religious fervor is rightly considered to be the least liable to musical misconstruction. … Foreigners who visit churches in Italy hear, to their amazement, the most popular themes from operas by Rossini, Bellini, Donizetti, and Verdi. Pieces like these and of a still more secular character, provided they do not altogether lose the quality of sobriety, are far from interfering with the devotions of the congregation, who, on the contrary, appear to be greatly edified. If music as such were capable of representing the feeling of Christian piety, the presence of music from operas in churches would be as unlikely as the contingency of a preacher reciting from the pulpit a romance novel or an act of Parliament. The greatest masters of sacred music afford abundant examples in proof of our proposition. Handel, in particular, set to work with the greatest nonchalance in this respect.

Winterfeld has shown that many of the most celebrated airs from The Messiah, including those most of all admired as being especially suggestive of piety, were taken from secular duets (mostly erotic) composed in the years 1711‐1712, when Handel set to music certain madrigals by Mauro Ortensio for the Electoral Princess Caroline of Hanover. The music of the second duet [with the words “No I will not trust you/Blind love, cruel beauty/You are too deceitful] … Handel employed unaltered both in key and melody for the chorus in the first part of The Messiah, ʺFor unto us a Child is born.ʺ … There is a vast number of similar instances, but we need only refer here to the entire series of pastoral pieces from the ʺChristmas Oratorioʺ which, as is well known, were naively taken from secular cantatas composed for special occasions. …

The dance is a similar case in point, of which any ballet is a proof. The more the graceful rhythm of the figures is sacrificed in the attempt to speak by gesture and dumb show, and to convey definite thoughts and emotions, the closer is the approximation to the low rank of mere pantomime. The prominence given to the dramatic principle in the dance proportionately lessens its rhythmical and plastic beauty. The opera can never be quite on a level with recited drama or with purely instrumental music. A good opera composer will, therefore, constantly endeavor to combine and reconcile the two factors instead of automatically emphasizing now one and now the other. When in doubt, however, he will always allow the claim of music to prevail, the chief element in the opera being not dramatic but musical beauty. …

To the question: What is to be expressed with all this material?, the answer will be: musical ideas. Now, a musical idea reproduced in its entirety is not only an object of intrinsic beauty but also an end in itself, and not a means for representing feelings and thoughts.

The essence of music is sound and motion.

4.3 Bell and Significant Form

A number of writers have proposed that the rise of abstract art in the 20th century justifies extension of Hanslick’s views about music into the realm of visual art. If music can be an art form without representing anything, then so can visual art. We are talking, of course, about artworks where the abstraction is meant to be the focus of sustained attention. Non-representational patterns have always been present in the decorative arts, which were therefore seen as something distinct from the fine arts.

Strictly speaking, abstraction means to purify something by removing distracting or impure elements. Understood in this way, Batteux was already praising all art as a vehicle of abstraction back in the 18th century. And Hanslick and others were praising instrumental music as a mode of abstract art. The historical change was that a greater degree of abstraction was becoming common in the visual arts at the start of the 20th century. What Ernest Hemingway said of bankruptcy applies to visual abstraction: it happened gradually, then suddenly.

Consider the painting Mont Sainte-Victoire, created by Paul Cézanne at the start of the 20th century. (See figure 4.7.) It is not classified as abstract art. After all, the landscape is easily seen. Yet paintings such as Cézanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire were moving in the direction of pure abstraction, reducing elements of nature to pure geometry.

Clive Bell was one of the first art critics outside France to defend the value of Cézanne’s work. Together with art critic Roger Fry, Bell organized an important exhibition of post-impressionist painting in London. Bell wrote several essays for the exhibition catalogue, and this led him to produce a full-blown defense of abstract art. The book Art was published in 1914. Most of the public disliked this kind of painting, and Bell attempted to validate the kind of work that was being done by Cezanne and Henri Matisse and, in England, by his wife, Vanessa Bell (sister of Virginia Woolf).

Although others paved the way, Bell’s book Art is the first full-blown defense of formalism as the unifying element of the visual arts.

Bell defends two ideas that are directly analogous to points made by Hanslick.

- Visual art can and should be evaluated as pure form, for the sake of its aesthetic properties.

- Quite apart from any expression of human emotions, pure form can itself be emotionally powerful.

According to Bell, a powerful design, which he calls “significant form,” is the fundamental and essential quality of a work of art. A significant form is one that makes a strong aesthetic impact. The impact that he describes in the following excerpt is one that 21st-century psychology identifies as a deep flow state, an immersive experience of complete absorption in what one encounters.

Bell proposes that artists in every culture have pursued significant form. However, its importance has been obscured by the presence of representation and narrative content. In other cases, it is obscured by the artist’s emphasis on emotional expression. Yet significant form is the basis of the universal and timeless appeal of great works of art. When a design has significant form, its impact will transcend cultural and historical barriers.

Bell notes that he is purposely avoiding the word “beauty” because that word is frequently applied to scenes and objects in nature. However, nature does not reveal the purified forms that are the special focus of artworks. Thus, Cézanne’s paintings of landscapes look beyond the “beauty” of the natural scene in order to reveal the form that underlies and shapes it.

Bell’s theory is not a complete break from earlier philosophy of art. He hangs on to the idea that the purpose of art is to infect us with powerful emotion. However, he is not interested in the everyday “emotions of life.” They are what we escape from when we encounter successful art! The aesthetic power of art is its capacity to give us an emotion that is otherwise hard to have, namely “the aesthetic emotion.” (This view is a variant of a view that has been defended since the 18th century, which holds that beauty has a special power to transfix us in a powerful yet “disinterested” pleasure.) Since the same aesthetic response is provoked by both representational art and abstract art, it must have the same source in both cases. Therefore, Bell concludes, abstract form is the source of all aesthetic value and is the primary source of the pleasure we get from art.

On this approach, the best examples of the decorative arts (e.g., graphic design, jewelry) turn out to be just as legitimate as poetry, sculpture, and painting. Bell says that a Chinese carpet can be just as good as an Impressionist painting.

Does this mean that a grilled cheese sandwich can be a work of art? No. The pleasing sensory experience of a good sandwich is not really a response to a structured design. (There is, of course, a recipe, but there is no design perceived by the tongue in the process of eating it.) Likewise, perfume or a scented candle can provide a pleasant smell, but our sense of smell does not perceive them as having a structured design. Thus, there are aesthetic properties other than significant form. What makes art special is its concentration on significant form. (To be fair, some writers have argued in response that the time-release of tastes and smells can give them a structure that provides some significant form.)

The great irony is that Bell was not aware when he was writing the book that fully abstract paintings had recently been created in other countries. Full abstraction had recently been achieved by Hilma af Klint, a Swedish painter, and Wassily Kandinsky, a Russian painter. Unfortunately, af Klilnt’s paintings received limited display during her lifetime and then her work was hidden away after her death. Consequently, she had limited influence on others. Kandinsky, on the other hand, promoted the virtue of abstract art, and his work influenced many other 20th-century artists. (See figure 4.8.) Vanessa Bell made the move to completely abstract art in several paintings in 1914, the same year that Clive Bell published his defense of formalism.

Excerpt from Clive Bell, Art (1914)

It is improbable that more nonsense has been written about aesthetics than about anything else: the literature of the subject is not large enough for that. It is certain, however, that about no subject with which I am acquainted has so little been said that is at all to the purpose. The explanation is discoverable. He who would elaborate a plausible theory of aesthetics must possess two qualities — artistic sensibility and a turn for clear thinking. Without sensibility a man can have no aesthetic experience, and, obviously, theories not based on broad and deep aesthetic experience are worthless. Only those for whom art is a constant source of passionate emotion can possess the data from which profitable theories may be deduced; but to deduce profitable theories even from accurate data involves a certain amount of brain‐work, and, unfortunately, robust intellects and delicate sensibilities are not inseparable. As often as not, the hardest thinkers have had no aesthetic experience whatever. I have a friend blessed with an intellect as keen as a drill, who, though he takes an interest in aesthetics, has never during a life of almost forty years been guilty of an aesthetic emotion. So, having no faculty for distinguishing a work of art from a handsaw, he is apt to rear up a pyramid of argument on the hypothesis that a handsaw is a work of art. …

The starting‐point for all systems of aesthetics must be the personal experience of a peculiar emotion. The objects that provoke this emotion we call works of art. All sensitive people agree that there is a peculiar emotion provoked by works of art. I do not mean, of course, that all works provoke the same emotion. On the contrary, every work produces a different emotion. But all these emotions are recognisably the same in kind; so far, at any rate, the best opinion is on my side. That there is a particular kind of emotion provoked by works of visual art, and that this emotion is provoked by every kind of visual art, by pictures, sculptures, buildings, pots, carvings, textiles, etc., etc., is not disputed, I think, by anyone capable of feeling it. This emotion is called the aesthetic emotion; and if we can discover some quality common and peculiar to all the objects that provoke it, we shall have solved what I take to be the central problem of aesthetics. We shall have discovered the essential quality in a work of art, the quality that distinguishes works of art from all other classes of objects.

For either all works of visual art have some common quality, or when we speak of ʺworks of artʺ we gibber. Everyone speaks of ʺart,ʺ making a mental classification by which he distinguishes the class ʺworks of artʺ from all other classes. What is the justification of this classification? What is the quality common and peculiar to all members of this class? Whatever it be, no doubt it is often found in company with other qualities; but they are adventitious — it is essential. There must be some one quality without which a work of art cannot exist; possessing which, in the least degree, no work is altogether worthless. What is this quality? What quality is shared by all objects that provoke our aesthetic emotions? What quality is common to [Saint] Sophia and the windows at Chartres, Mexican sculpture, a Persian bowl, Chinese carpets, Giotto’s frescoes at Padua, and the masterpieces of Poussin, Piero della Francesca, and Cezanne? Only one answer seems possible — significant form. In each, lines and colours combined in a particular way, certain forms and relations of forms, stir our aesthetic emotions. These relations and combinations of lines and colours, these aesthetically moving forms, I call ʺSignificant Formʺ; and ʺSignificant formʺ is the one quality common to all works of visual art.

At this point it may be objected that I am making aesthetics a purely subjective business …. Aesthetic judgments are, as the saying goes, matters of taste; and about tastes, as everyone is proud to admit, there is no disputing. A good critic may be able to make me see in a picture that had left me cold things that I had overlooked, till at last, receiving the aesthetic emotion, I recognise it as a work of art. To be continually pointing out those parts, the sum, or rather the combination, of which unite to produce significant form, is the function of criticism. But it is useless for a critic to tell me that something is a work of art; he must make me feel it for myself. This he can do only by making me see; he must get at my emotions through my eyes. Unless he can make me see something that moves me, he cannot force my emotions. I have no right to consider anything a work of art to which I cannot react emotionally; and I have no right to look for the essential quality in anything that I have not felt to be a work of art. The critic can affect my aesthetic theories only by affecting my aesthetic experience. All systems of aesthetics must be based on personal experience — that is to say, they must be subjective.

Yet it would be rash to assert that no theory of aesthetics can have general validity. For, though A, B, C, D are the works that move me, and A, D, E, F the works that move you, it may well be that x is the only quality believed by either of us to be common to all the works in his list. We may all agree about aesthetics, and yet differ about particular works of art. We may differ as to the presence or absence of the quality x. My immediate object will be to show that significant form is the only quality common and peculiar to all the works of visual art that move me; and I will ask those whose aesthetic experience does not tally with mine to see whether this quality is not also, in their judgment, common to all works that move them, and whether they can discover any other quality of which the same can be said. …

ʺAre you forgetting about colour?ʺ someone inquires. Certainly not; my term ʺsignificant formʺ included combinations of lines and of colours. The distinction between form and colour is an unreal one; you cannot conceive a colourless line or a colourless space; neither can you conceive a formless relation of colours. In a black and white drawing the spaces are all white and all are bounded by black lines; in most oil paintings the spaces are multi‐coloured and so are the boundaries; you cannot imagine a boundary line without any content, or a content without a boundary lines. Therefore, when I speak of significant form, I mean a combination of lines and colours (counting white and black as colours) that moves me aesthetically.

The hypothesis that significant form is the essential quality in a work of art has at least one merit denied to many more famous and more striking — it does help to explain things. We are all familiar with pictures that interest us and excite our admiration, but do not move us as works of art. To this class belongs what I call ʺDescriptive Paintingʺ that is, painting in which forms are used not as objects of emotion, but as means of suggesting emotion or conveying information. Portraits of psychological and historical value, topographical works, pictures that tell stories and suggest situations, illustrations of all sorts, belong to this class.

That we all recognise the distinction is clear, for who has not said that such and such a drawing was excellent as illustration, but as a work of art worthless? Of course many descriptive pictures possess, amongst other qualities, formal significance, and are therefore works of art; but many more do not. They interest us; they may move us too in a hundred different ways, but they do not move us aesthetically. According to my hypothesis they are not works of art. They leave untouched our aesthetic emotions because it is not their forms but the ideas or information suggested or conveyed by their forms that affect us. …

Let no one imagine that representation is bad in itself; a realistic form may be as significant, in its place as part of the design, as an abstract. But if a representative form has value, it is as form, not as representation. The representative element in a work of art may or may not be harmful; always it is irrelevant. For, to appreciate a work of art we need bring with us nothing from life, no knowledge of its ideas and affairs, no familiarity with its emotions. Art transports us from the world of manʹs activity to a world of aesthetic exaltation. For a moment we are shut off from human interests; our anticipations and memories are arrested; we are lifted above the stream of life. The pure mathematician rapt in his studies knows a state of mind which I take to be similar, if not identical. He feels an emotion for his speculations which arises from no perceived relation between them and the lives of men, but springs, inhuman or super‐human, from the heart of an abstract science.

I wonder, sometimes, whether the appreciators of art and of mathematical solutions are not even more closely allied. Before we feel an aesthetic emotion for a combination of forms, do we not perceive intellectually the rightness and necessity of the combination? If we do, it would explain the fact that passing rapidly through a room we recognise a picture to be good, although we cannot say that it has provoked much emotion. We seem to have recognised intellectually the rightness of its forms without staying to fix our attention, and collect, as it were, their emotional significance. If this were so, it would be permissible to inquire whether it was the forms themselves or our perception of their rightness and necessity that caused aesthetic emotion. But I do not think I need linger to discuss the matter here. I have been inquiring why certain combinations of forms move us; I should not have traveled by other roads had I enquired, instead, why certain combinations are perceived to be right and necessary, and why our perception of their rightness and necessity is moving. What I have to say is this: the rapt philosopher, and he who contemplates a work of art, inhabit a world with an intense and peculiar significance of its own; that significance is unrelated to the significance of life. In this world the emotions of life find no place. It is a world with emotions of its own.

To appreciate a work of art we need bring with us nothing but a sense of form and colour and a knowledge of three‐dimensional space. That bit of knowledge, I admit, is essential to the appreciation of many great works, since many of the move moving forms ever created are in three dimensions. To see a cube or rhomboid as a flat pattern is to lower its significance, and a sense of three‐dimensional space is essential to the full appreciation of most architectural forms. Pictures which would be insignificant if we saw them as flat patterns are profoundly moving because, in fact, we see them as related planes. If the representation of three‐dimensional space is to be called ʺrepresentation,ʺ then I agree that there is one kind of representation which is not irrelevant. Also, I agree that along with our feeling for line and colour we must bring with us our knowledge of space if we are to make the most of every kind of form. Nevertheless, there are magnificent designs to an appreciation of which this knowledge is not necessary: so, though it is not irrelevant to the appreciation of some works of art it is not essential to the appreciation of all. What we must say is that the representation of three‐dimensional space is neither irrelevant nor essential to all art, and that every other sort of representation is irrelevant.

That there is an irrelevant representative or descriptive element in many great works of art is not in the least surprising. Why it is not surprising I shall try to show elsewhere. Representation is not of necessity baneful, and highly realistic forms may be extremely significant. Very often, however, representation is a sign of weakness in an artist. A painter too feeble to create forms that provoke more than a little aesthetic emotion will try to eke that little out by suggesting the emotions of life. To evoke the emotions of life he must use representation. Thus a man will paint an execution, and, fearing to miss with his first barrel of significant form, will try to hit with his second by raising an emotion of fear or pity. But if in the artist an inclination to play upon the emotions of life is often the sign of a flickering inspiration, in the spectator a tendency to seek, behind form, the emotions of life is a sign of defective sensibility always. It means that his aesthetic emotions are weak or, at any rate, imperfect.

Before a work of art people who feel little or no emotion for pure form find themselves at a loss. They are deaf men at a concert. They know that they are in the presence of something great, but they lack the power of apprehending it. They know that they ought to feel for it a tremendous emotion, but it happens that the particular kind of emotion it can raise is one that they can feel hardly or not at all. And so they read into the forms of the work those facts and ideas for which they are capable of feeling emotion, and feel for them the emotions that they can feel — the ordinary emotions of life. When confronted by a picture, instinctively they refer back its forms to the world from which they came. They treat created form as though it were imitated form, a picture as though it were a photograph. Instead of going out on the stream of art into a new world of aesthetic experience, they turn a sharp corner and come straight home to the world of human interests. For them the significance of a work of art depends on what they bring to it; no new thing is added to their lives, only the old material is stirred. A good work of visual art carries a person who is capable of appreciating it out of life into ecstasy: to use art as a means to the emotions of life is to use a telescope of reading the news. You will notice that people who cannot feel pure aesthetic emotions remember pictures by their subjects; whereas people who can, as often as not, have no idea what the subject of a picture is. They have never noticed the representative element, and so when they discuss pictures they talk about the shapes of forms and the relations and quantities of colours. Often they can tell by the quality of a single line whether or not a man is a good artist. They are concerned only with lines and colours, their relations and quantities and qualities; but from these they win an emotion more profound and far more sublime than any that can be given by the description of facts and ideas.

This last sentence has a very confident ring — over‐confident, some may think. Perhaps I shall be able to justify it, and make my meaning clearer too, if I give an account of my own feelings about music. I am not really musical. I do not understand music well. I find musical form exceedingly difficult to apprehend, and I am sure that the profounder subtleties of harmony and rhythm more often than not escape me. The form of a musical composition must be simple indeed if I am to grasp it honestly. My opinion about music is not worth having. Yet, sometimes, at a concern, though my appreciation of the music is limited and humble, it is pure. Sometimes, though I have poor understanding, I have a clean palate. Consequently, when I am feeling bright and clear and intent, at the beginning of a concert for instance, when something that I can grasp is being played, I get from music that pure aesthetic emotion that I get from visual art. It is less intense, and the rapture is evanescent; I understand music too ill for music to transport me far into the world of pure aesthetic ecstasy. But at moments I do appreciate music as pure musical form, as sounds combined according to the laws of a mysterious necessity, as pure art with a tremendous significance of its own and no relation whatever to the significance of life; and in those moments I lose myself in that infinitely sublime state of mind to which pure visual form transports me. How inferior is my normal state of mind at a concert. Tired or perplexed, I let slip my sense of form, my aesthetic emotion collapses, and I begin weaving into the harmonies, that I cannot grasp, the ideas of life. Incapable of feeling the austere emotions of art, I begin to read into the musical forms human emotions of terror and mystery, love and hate, and spend the minutes, pleasantly enough, in a world of turbid and inferior feeling. At such times, were the grossest pieces of [imitation] — the song of a bird, the galloping of horses, the cries of children, or the laughing of demons — to be introduced into the symphony, I should not be offended. Very likely I should be pleased; they would afford new points of departure for new trains of romantic feeling or heroic thought. I know very well what has happened. I have been using art as a means to the emotions of life and reading into it the ideas of life. I have been cutting blocks with a razor. I have tumbled from the superb peaks of aesthetic exaltation to the snug foothills of warm humanity. It is a jolly country. No one need to ashamed of enjoying himself there. Only no one who has ever been on the heights can help feeling a little crestfallen in the cosy valleys. And let no one imagine, because the has made merry in the warm tilth and quaint nooks of romance, that he can even guess at the austere and thrilling raptures of those who have climbed the cold, white peaks of art.

I am certain that most of those who visit galleries do feel very much what I feel at concerts. They have their moments of pure ecstasy; but the moments are short and unsure. Soon they fall back into the world of human interests and feel emotions, good no doubt, but inferior. I do not dream of saying that what they get from art is bad or nugatory; I say that they do not get the best that art can give. I do not say that they cannot understand art; rather I say that they cannot understand the state of mind of those who understand it best. I do not say that art means nothing or little to them; I say they miss its full significance. I do not suggest for one moment that their appreciation of art is a thing to be ashamed of; the majority of the charming and intelligent people with whom I am acquainted appreciate visual art impurely; and, by the way, the appreciation of almost all great writers has been impure. But provided that there be some fraction of pure aesthetic emotion, even a mixed and minor appreciation of art is, I am sure, one of the most valuable things in the world — so valuable, indeed, that in my giddier moments I have been tempted to believe that art might prove the worldʹs salvation. …

The forms of art are inexhaustible; but all lead by the same road of aesthetic emotion to the same world of aesthetic ecstasy.

4.4. Bullough and Psychical Distancing

Bell considers the objection that aesthetic response is subjective, meaning that it is so variable that it cannot be predicted or controlled. But if that is true, then there is no reason for artists to care about it. Bell addresses this issue by trying to have it both ways. The aesthetic response is indeed subjective and unpredictable. In his own case, he can respond to visual art but has limited aesthetic response to music. To know if a specific work of art is good and worth our time, we have to ask those who are sensitive to the specific artistic medium. If we ask them what they find highly significant, they generally agree about which aspects of a specific art work are most significant. This turns out to be significant form. Therefore, there is an objective cause of the aesthetic emotion. Therefore, the issue of subjectivity does not bother Bell.

Notice that Bell believes that his thesis is subject to empirical testing. Strictly speaking, the process of carrying out such testing falls to psychology of art. Psychologists with an interest in art have done research on aesthetic response, classifying it as a fundamental human response to the world. Because we find it in almost every individual and we find it in every culture, it should not be dismissed as “subjective.” As a basic response mechanism, aesthetic response plays an important role in human life.

A classic example of a psychological account of aesthetic response is Edward Bullough’s account of psychical distancing. Rather than being an emotional response like fear or joy, an aesthetic response is a very special kind of mental orientation toward the world. It is an orientation that blurs the line between reality and subjectivity. Put simply, Bullough thinks that aesthetic response involves viewing reality as if it’s simply a representation. If correct, this explains why pictures and stories and other representations are a good way to bring about an aesthetic response. At the same time, his theory cautions against the move to abstraction recommended by Bell and other formalists. Abstraction, Bullough warns, is not going to trigger an aesthetic response in the average person. It will only appeal to a limited subset of art lovers. In other words, he predicted in 1912 that the rise of abstract visual art is not going to put representational artists out of business. A representational painting by Mary Cassatt (see figure 4.12) is more likely to succeed aesthetically with the average person than a painting by Kandinsky (see figure 4.8).

Bullough’s core proposal is that the realm of the aesthetic is produced by a specific psychological attitude adopted by the observer. For people who learn to control this psychological attitude, anything can be subjected to this response and thereby rendered aesthetic. A beautiful sunset will trigger it in almost anyone, but someone who has learned to control the response mechanism might find beauty by looking at a mosquito, at some rotting fruit, or the face of someone in pain. However, these people are psychological outliers. So, yes, some people will get the rewards intended from abstract art. But not most people.

The starting point of Bullough’s theory is the point that everyone has, at one time or another, felt detached. According to Bullough, psychical distancing is the ability to detach oneself emotionally from one’s situation, allowing for aesthetic appreciation in place of active engagement with one’s immediate circumstances. It is similar to, but not identical with, the fear response that can freeze someone in place. For example, when viewing a tragic event, such as visiting a child who is near death from childhood leukemia, most people will empathize with the child’s suffering. They will experience grief. Others will become emotionally detached, as if viewing a movie instead of a real event. For those in the latter category, the situation might be seen as having a kind of tragic beauty. This detached response is unlikely to happen to the child’s parents because they are too emotionally involved and too close, psychologically. However, if a parent becomes overwhelmed, they might become numb and detached, which is a kind of psychical distancing.

This sort of “distancing” permits us to experience the world aesthetically. This proposal is not original with Bullough. He is drawing on a long-standing tradition that aesthetic experience requires adoption of a disinterested stance. Disinterestedness does not mean a lack of interest, but rather a special kind of interest. It involves taking an interest in the appearance of things, suspending concern for how those things might have a personal or practical impact. This thesis was developed by a number of philosophers in the 18th century, most notably in the aesthetic theory of Immanuel Kant: “Taste is the faculty of judging an object or mode of representing it by an entirely disinterested satisfaction or dissatisfaction. The object of such satisfaction is called beautiful” (translation by J.H. Bernard). The hardest thing to evaluate aesthetically is one’s own artistic efforts, especially if it has a personal dimension. Great artists, in developing “taste,” develop the capacity to view their own work as if it was not theirs. This is a type of disinterestedness.

Building on this tradition, the theory of psychical distancing says that it involves a mindset that sets aside our everyday concerns and emotional responses, allowing us to engage more dispassionately with the world. It is a natural human response, and it helps protect our mental health during episodes of extreme stress or danger. Thus, Bullough offers a psychological explanation of why aesthetic response is a standard human capacity.

It is important to note that Bullough is concentrating on psychical distancing of perceived events and things. Thus, he is talking about aesthetic response. (Memory, in contrast, has a kind of distancing already built into it: the distance of time.) Art, then, is valuable for the way that encourages psychical distancing. Like so many others, Bullough is looking for a tight connection between aesthetics and art, promoting an aesthetic account of art’s value. At the same time, he puts aesthetic response into a larger psychological framework.

Basically, Bullough says that representational art encourages mental and emotional separation from the real world, allowing us to engage pleasurably with material even when it deals with unpleasant or tragic events. This distancing frees us from having an immediate personal or practical concern that would normally be associated with the work’s subject matter, enabling a fuller examination and contemplation of all of the artwork’s various qualities. It also allows for a more objective evaluation of the artwork’s form, structure, and meaning.

The theory is based on the psychological discovery that people cannot attend to everything they perceive. At any given time, your mind decides which aspects of your environment are (and are not) important to whatever project you’re pursuing at the present moment. If you go into a room looking for your car keys and see them on the table, you might not see that the overdue library book you misplaced and have been looking for is right beside your keys. Edgar Allan Poe’s short story The Purloined Letter (1844) is famous for building this phenomenon into a crime story. A thief hides a stolen document by leaving it in plain sight.

In psychical distancing, a person puts their practical concerns “out of gear.” This metaphor means that one sets the controls of a car so that the gear connecting the engine to the wheels is no longer connected. Bullough proposes that we can do something analogous with our minds. Awareness that we are dealing with something other than a practical reality when we engage in art will encourage us to put its subject matter “out of gear,” disconnecting the perceptual system from the part of our mind that filters perception according to our practical concerns. Once we stop filtering in relation to a practical project, we engage with subject matter that would be either ignored or that would be highly painful in ordinary life.

To put this crudely: you don’t actually see most of what is right in front of you. Your personal interests and goals guide your attention, filtering out most of what you encounter. Your personal emotions also get in the way of recognizing things for what they are. Shut off your egoism and shut off the mental filters you have been conditioned to employ, and you can see things more clearly, more objectively. The aesthetic response makes things more objective, not more subjective.

Bullough thinks that of the value of this psychological distancing is that we continue to have emotional response when this happens, but now the emotions are also within the field of what we can see more clearly. People respond emotionally to the subject matter of art, but (assuming they successfully distance) they simultaneously “distance” from that emotional response, treating it as another phenomenon in the mix of phenomena to be observed.

Horror and tragedy are good examples. Experiences that no one wants in real life are viewed with enjoyment. In fact, audiences seek out horror movies and tragedies because they will provoke the strong emotions of fear and pity, respectively. But these emotions will be “out of gear,” and observing the relationship of the artwork to the response becomes another enjoyable feature inspected by the viewer. Therefore, says Bullough, aesthetic experience is really the most objective kind of experience, because it makes our subjective responses more “impersonal” to us.

This creates something of a problem for artists. To deal with highly emotional subject matter, the artist has to treat it with psychical distance themselves, and then they have to find a way to show it to others in a way that encourages their audience to adopt the same attitude of psychical distancing. But artists become so good at psychical distancing that they frequently fail to measure how far they can go and still make their art accessible to most people. They forget that other people are not good at distancing, and they forget the ease with which difficult subject matter will cause psychological harm (under-distancing). Because physical separation and the passage of time help people to be less emotionally engaged with anything, physical distance and stories set in the past can be easier to handle if there is strong emotional content. Notice, in this regard, that Shakespeare set most of his plays in foreign countries, as if to signal to his London audience, “This story is about someone else, not you. Don’t take it personally.” But modern artists use this technique less and less, and so it is not a surprise that modern artists face the twin threats of censorship and a limited audience for what they produce.

Excerpt from Edward Bullough, “Psychical Distanceʹ as a Factor in Art and as an Aesthetic Principle.” British Journal of Psychology, Vol. 5 (1912)

PART I

(1) … A short illustration will explain what is meant by ʹPsychical Distance.ʹ Imagine a fog at sea; for most people it is an experience of acute unpleasantness. Apart from the physical annoyance and remoter forms of discomfort such as delays, it is apt to produce feelings of peculiar anxiety, fears of invisible dangers, strains of watching and listening for distant and unlocalised signals. The listless movements of the ship and her warning calls soon tell upon the nerves of the passengers; and that special, expectant, tacit anxiety and nervousness, always associated with this experience, make a fog the dreaded terror of the sea (all the more terrifying because of its very silence and gentleness) for the expert seafarer no less than the ignorant landsman.

Nevertheless, a fog at sea can be a source of intense relish and enjoyment. Abstract from the experience of the sea fog, for the moment, its danger and practical unpleasantness, just as every one in the enjoyment of a mountain‐climb disregards its physical labour and its danger (though, it is not denied, that these may incidentally enter into the enjoyment and enhance it); direct the attention to the features ʹobjectivelyʹ constituting the phenomenon — the veil surrounds you with an opaquensss as of transparent milk, blurring the outline of things and distorting their shapes into weird grotesqueness; observe the carrying‐power of the air, producing the impression as if you could touch some far‐off siren by merely putting out your hand and letting it lose itself behind that white wall; note the curious creamy smoothness of the water, hypocritically denying as it were any suggestion of dancer; and, above all, the strange solitude and remoteness from the world, as it can be found only on the highest mountain tops; and the experience may acquire, in its uncanny mingling of repose and terror, a flavour of such concentrated poignancy and delight as to contrast sharply with the blind and distempered anxiety of its other aspects. This contrast, often emerging with startling suddenness, is like a momentary switching on of some new current, or the passing ray of a brighter light, illuminating the outlook upon perhaps the most ordinary and familiar objects — an impression which we experience sometimes in instants of direct extremity, when our practical interest snaps like a wire from sheer over‐tension, and we watch the consummation of some impending catastrophe with the marvelling unconcern of a mere spectator.

It is a difference of outlook, due — if such a metaphor is permissible — to the insertion of distance. This distance appears to lie between our own self and its affections, using the latter term in its broadest sense as anything which affects our being, bodily or spiritually, e.g., as sensation, perception, emotional state or idea. Usually, though not always, it amounts to the same thing to say that the Distance lies between our own self and such objects as are the sources or vehicles of such affections.