2 Art, Creativity, and Genius

Theodore Gracyk

Key Takeaways for Art, Creativity, and Genius

Topic: Does artistic genius explain creativity and originality?

From the Italian Renaissance until today, genius has been aligned with great art

Genius is supposed to be a natural talent that cannot be acquired from education

The essential contribution of genius distinguishes fine art from other human activities

Unrestricted genius can produce bad art

William Shakespeare has often served as a test case for this topic

Virginia Woolf argued that genius is of little or no importance to artistic accomplishment

2.1 Chapter Introduction

Philosophy has been described as the activity of thinking about thinking. Where psychology aims to explain how our minds work, the tradition of European and American philosophy aims to identify the most basic content of our thinking. In modern philosophy, this work is known as conceptual analysis. This analysis is considered a basic step in determining which ways of thinking should be retained and which should be replaced. In other words, philosophers examine concepts and try to determine which concepts generate confusion rather than clarity. A concept can become outdated, coming into conflict with newer ideas. Or it can be incoherent, containing multiple strands that do not align with each other. The task of conceptual analysis leads to a second major task of philosophy, which is to suggest revision (or even rejection) of misleading concepts and assumptions. Philosophers work to sort out the different components of the concept in order to show how it might be employed in a clearer way, so that it no longer creates confusions. The point, of course, is that most people don’t realize that they are being confused by concepts that are in wide use.

This chapter focuses on a core concept employed in European thinking about art from the Renaissance until today: artistic genius. Section 2.2 focuses on an influential analysis of the concept written by Immanuel Kant. Section 2.3 will then provide a 20th-century evaluation from the perspective of feminism, with an excerpt from Virginia Woolf. Section 2.4 backtracks to illustrate that Woolf’s main example (Shakespeare and his sister) is even more complicated than she indicates. It was not obvious to earlier generations that Shakespeare should be used to illustrate the category of literary genius.

One way that concepts are confused (and confusing) is that they have connotations. That is, they have associated meanings that supplement their primary meanings. As a result, most concepts have multiple implications, which may or may not be clear to many of those who use them. These associations and implications are generally the result of historical developments. To understand a concept, it is often necessary to understand why the concept arose when it did, and what associations it carries as a result. To see the significance of this point, it is crucial to recall one of the lessons of Chapter 1: concepts that we take for granted have not been around forever. In the same way that the distinction between analogue and digital coding is a 20th-century development, the distinction between “fine art” and other communication is an 18th-century development. Social explanations of personal development and behavior were not yet common in the 18th century. Consequently, the concept of art still retains connotations or assumptions that deny or downplay the social dimension of artistic activity.

In the readings in Chapter 1, both Giorgio Vasari and Charles Batteux stress the connection between art and genius. Batteux says that successful art is produced by “privileged souls” who possess an innate talent for “enthusiasm.” By the end of the 18th century, genius was firmly embedded as a foundational connotation of the concept of art. Anyone might paint a picture or write a story, but only a person who possesses genius can create a story or picture that qualifies as fine art. (This idea informs Alfred Stieglitz’s proposal, in Chapter 1, that few photographs qualify as fine art.)

The current chapter contrasts two very different positions on artistic genius. The first is favorable about it, and the second is unfavorable.

The first excerpt is from Immanuel Kant, who is generally regarded as the most significant philosopher of the 18th century. Perhaps more than anyone, his writing on fine art cemented together the ideas of fine art and genius. The second reading is by a 20th-century novelist and essayist, Virginia Woof. She was one of the first to call attention to another connotation of artistic genius, which is the long-standing assumption that only men can possess it. (Go back and review Vasari, and notice that he explicitly talks of “men of genius.” 99% of the artists he profiled were men.) Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own joins a tradition of feminist philosophy that dates back to the Renaissance. It challenges the association of art and genius by attacking the underlying assumption that genius is a masculine quality.

2.2 Immanuel Kant on Artistic Genius

Immanuel Kant is generally considered to be the most important figure in modern philosophy. Late in his career, he turned his attention to the topics of aesthetic experience and art, and his writings on that topic are the foundation of modern philosophy of art. It would be difficult overstate how influential he was, not least of all for insisting that aesthetic value is one of the central topics of philosophy. Unfortunately, his philosophical writing is highly technical and can be very difficult to read. Thankfully, his discussion of artistic genius is somewhat more accessible than most of his writing. For our purposes in this chapter, his key teaching is that art is necessarily the result of “natural” genius. Kant’s support for this idea made it a key doctrine in aesthetics, art theory, art history, and literary theory.

True to his times, Kant regards beauty as an essential element of fine art. However, he also develops a theory that looks forward to Romanticism: genius is a mysterious power of imagination that produces innovative expression of complex ideas.

Successful art, Kant argues, is guided by the “guardian spirit” of genius, which upon close inspection turns out to be a vivid imagination that creates complex and often surprising associations among ideas. Artistic genius is traced to an ordinary mental ability (imagination) that operates in an unusual manner. However, excessive imagination can lead to excessive originality: it is just as likely to produce garbage as gold. If the art produced by a genius is too imaginative, the audience will not understand it. Since art is made for others to experience, Kant proposes that a good artist will strike a balance between the two extremes of being merely entertaining and being disorganized and confusing. This does not mean that Kant looks down on entertainment: the Critique of Judgement has an interesting segment on the entertainment value of jokes. But fine art is supposed to do more than entertain. Insight is needed to transform entertaining diversions into fine art, which, following Batteux, is expected to please the audience with its beauty. Beauty is recognized by “taste.”

Complex combinations of ideas that are too original will violate taste, because it will seem to the audience that the different aspects of the work will not hang together in advancing its communicative purpose. It will be puzzling or incoherent instead of pleasing. Kant’s view on this particular point is common. For example, Francis Ford Coppola’s film Megalopolis (2024) was widely criticized for just this reason, with one critic warning that it is “a glorious mess, an undeniable mess, a mess of too much ambition, too many ideas, too many characters and not enough discipline” (Ty Burr, The Washington Post, September 25, 2024).

Echoing Vasari’s account of the life of da Vinci, Kant accepts the view that no one can be trained to use their imagination in the way that genius uses it. The power to produce original artistic content cannot be taught or learned. For this reason, Kant says that the appearance of genius in an individual and in any artwork is a display of “nature” rather than “culture.” (The standard meaning of “culture” aligns it with the core practices, beliefs, and values that are taught by one generation to the next. If something can’t be taught, it can’t be classified as culture.)

Genius, then, is an unpredictable intervention into art history that changes the course of that history. Thanks to those lucky few who posses genius, natural talent disrupts and redirects culture. This point is important to Kant because he thinks it explains how art is radically different from science. Issac Newton was a scientific genius, but in retrospect we can see exactly how he worked out the mathematics that led to his great breakthroughs in physics. The same does not hold for artists. After-the-fact critical examination never explains how an artistic breakthroughs happened. Therefore, artistic genius produces a more radical originality than scientific genius. Where science describes nature, artistic genius is nature at work within us.

When Kant says that the fine arts “must necessarily be considered as arts of genius,” he does not mean that each and every valuable artwork is produced by an artistic genius.

Genius might be present second-hand, through the imitation of a breakthrough by an artistic genius. Works of genius serve as “models” for subsequent generations of artists. For example, Pablo Picasso is generally regarded as the founder of cubist painting, and Fernand Léger is considered one of the best cubist painters. (See figure 2.1.) However, Léger learned the basics of how to represent things in cubist style by imitating elements of Picasso’s work. For Kant, Picasso’s genius informs Léger’s art (rather than Léger’s personal genius). Had it not been for Picasso, there might not have been any cubist art at all. In this way, fine art differs from the “mechanical” arts. Remember, from Chapter 1, that in Kant’s time “art” meant the broad category of skill in producing hand-made goods, and the arts divided between the mechanical arts, producing functional items such as baskets and shoes, and the fine arts, which are primarily valued for beauty and the presentation of ideas.

Thus, for Kant, someone can be a perfectly good artist without being a genius. The great majority of working artists are simply imitating the path laid out by artistic genius. Most art is derivative, and derivative fine art reflects someone else’s genius. Picasso’s cubist breakthrough “gives the rule” to later artists, such as Léger. By definition, geniuses are the ones that less talented artists copy and imitate. Because genius changes the rules of art and thus art history, the idea of an unrecognized genius is basically a contradiction in terms in Kant’s philosophy. Art history tells us which artists possessed genius, for it tells us who had a major impact on subsequent artists.

The plays of William Shakespeare have often served as a focal point in ongoing debates about the nature and value of genius and creativity. (Virginia Woolf discusses him in the excerpt provided in Section 2.3 below.) Although Kant does not mention Shakespeare in his major contribution to philosophy of art, The Critique of Judgement, he does so in other writing. Kant praises Shakespeare for turning theatrical entertainment into fine art that explores the human condition. However, Kant’s praise is qualified by criticism. He regards Shakespeare as an overly-imaginative genius who should have engaged in more self-editing. Writing for the theater, Shakespeare never learned to “clip” the wings of his genius. He broke too many rules, and too often. His plays are self-indulgent, with verbal displays that do not contribute to his writing’s primary themes. Some of his plays lack good form, that is, they are unstructured and contain scenes that can be removed without loss to the overall effect.

Kant’s evaluation was not unusual for his time. Section 2.4 contains an analysis of Shakespeare written by David Hume, another 18th-century philosopher. This passage from Hume illustrates that many educated people of that time were not impressed by Shakespeare’s plays. In fact, when the plays were performed prior to the 20th century, they were heavily edited to remove their many perceived defects. Outside of England, Shakespeare only gained positive status with the rise of Romanticism, a philosophical movement that developed toward the end of the 18th century, after Hume’s death and near the end of Kant’s lifetime. The German Romantics praised the originality of genius above every other quality, and this led to greater tolerance of the flaws that bothered Kant and Hume. The spread of Romantic philosophy made Shakespeare more popular outside of England.

If one applies what Kant says about genius, the justification for regarding Shakespeare as a genius is that others were inspired by his work. Yet he was not especially popular until the Romantics “rediscovered” him and promoted him. So, Kant’s philosophy says that Shakespeare’s genius took an unusually long time to reveal itself. Thus, Shakespeare serves as an important model for the Romantic doctrine that many geniuses are ahead of their time and are under-appreciated in their own lifetime. Ironically, the English poet and critic Samuel Taylor Coleridge probably did the most to renew interest in Shakespeare at the start of the 19th century. In doing so, he borrowed heavily from Kant and other German philosophers, applying their ideas to English literature. Indirectly, therefore, Kant played an important role in the eventual elevation of Shakespeare to the status of literary genius.

In summary, the idea that a handful of artists have the special capacity of “genius” is offered to explain why art has a history, that is, why it changes. The appearance of a new genius in an art form changes the rules of the game, providing a “precedent rule” (an innovative approach that other artists imitate). After that, art “stands still” until a new genius shakes up the art establishment. (For more on Kant’s views, see Chapter 5.)

Immanuel Kant: Excerpt from The Critique of Judgment (1790), translation by J. H. Bernard

Section 46: Beautiful Art is the art of genius

[Important note about translation: when Kant says “beautiful art,” that is a literal translation of the German schöne Kunst, which is the German phrase distinguishing fine art from entertainment and craft]

Genius is the talent (or natural gift) which gives the rule to art. Since talent, as the innate productive faculty of the artist, belongs itself to nature, we may express the matter thus: Genius is the innate mental disposition (ingenium) through which nature gives the rule to art.

Whatever may be thought of this definition, whether it is merely arbitrary or whether it is adequate to the concept that we are accustomed to combine with the word genius (which is to be examined in the following paragraphs), we can prove already beforehand that according to the signification of the word here adopted, beautiful arts must necessarily be considered as arts of genius.

For every art presupposes rules by means of which in the first instance a product, if it is to be called artistic, is represented as possible. But the concept of beautiful art does not permit the judgement upon the beauty of a product to be derived from any rule, which has a concept as its determining ground, and therefore has at its basis a concept of the way in which the product is possible. Therefore, beautiful art cannot itself devise the rule according to which it can bring about its product. But since at the same time a product can never be called art without some precedent rule, nature must (by the harmony of its faculties [of imagination and understanding]) give the rule to art; i.e. beautiful art is only possible as a product of genius.

We thus see

(1) that genius is a talent for producing that for which no definite rule can be given; it is not a mere aptitude for what can be learnt by a rule. Hence originality must be its first property.

(2) But since it also can produce original nonsense, its products must be models, i.e. exemplary; and they consequently ought not to spring from imitation, but must serve as a standard or rule of judgement for others.

(3) It cannot describe or indicate scientifically how it brings about its products, but it gives the rule just as nature does. Hence the author of a product for which he is indebted to his genius does not himself know how he has come by his Ideas; and he has not the power to devise the like at pleasure or in accordance with a plan, and to communicate it to others in precepts that will enable them to produce similar products. (Hence it is probable that the word genius is derived from [the Latin word] genius, that peculiar guiding and guardian spirit given to a man at his birth, from whose suggestion these original Ideas proceed.)

(4) Nature by the medium of genius does not prescribe rules to science, but to art; and to it only in so far as it is to be beautiful art.

Section 47: Elucidation and confirmation of the above explanation of Genius

Every one is agreed that genius is entirely opposed to the spirit of imitation. Now since learning is nothing but imitation, it follows that the greatest ability and teachableness (capacity) … cannot avail for genius. Even if a man thinks or invents for himself, and does not merely take in what others have taught, even if he discovers many things in art and science, this is not the right ground for calling such a (perhaps great) mind, a genius (as opposed to him who because he can only learn and imitate is called shallow). For even these things could be learned, they lie in the natural path of him who investigates and reflects according to rules; and they do not differ specifically from what can be acquired by industry through imitation. Thus we can readily learn all that [Isaac] Newton has set forth in his immortal work on the Principles of Natural Philosophy, however great a head was required to discover it; but we cannot learn to write spirited poetry, however express may be the precepts of the art and however excellent its models. The reason is that Newton could make all his steps, from the first elements of geometry to his own great and profound discoveries, intuitively plain and definite as regards consequence, not only to himself but to every one else. But a Homer or a Wieland cannot show how his ideas, so rich in fancy and yet so full of thought, come together in his head, simply because he does not know and therefore cannot teach others. In science then the greatest discoverer only differs in degree from his laborious imitator and pupil; but [a derivative artist] differs specifically from him whom nature has gifted for beautiful art. And in this there is no depreciation of those great [scientists] to whom the human race owes so much gratitude, as compared with nature’s favourites in respect of the talent for beautiful art. For in the fact that [scientific] talent is directed to the ever-advancing greater perfection of knowledge and every advantage depending on it, and at the same time to the imparting this same knowledge to others — in this it has a great superiority over [the talent of] those who deserve the honour of being called geniuses. For art stands still at a certain point; a boundary is set to it beyond which it cannot go. …

Again, artistic skill cannot be communicated; it is imparted to every artist immediately by the hand of nature; and so it dies with him, until nature endows another in the same way, so that he only needs an example in order to put in operation in a similar fashion the talent of which he is conscious.

If now it is a natural gift which must prescribe its rule to art (as beautiful art), of what kind is this rule? It cannot be reduced to a formula and serve as a precept, for then the judgement upon the beautiful would be determinable according to concepts; but the rule must be abstracted from the fact, i.e. from the product, on which others may try their own talent by using it as a model, not to be copied but to be imitated. How this is possible is hard to explain. The ideas of the artist excite like ideas in his pupils if nature has endowed them with a like proportion of their mental powers. Hence models of beautiful art are the only means of handing down these ideas to posterity. This cannot be done by mere descriptions, especially not in the case of the arts of speech …

Although mechanical and beautiful art are very different, the first being a mere art of industry and learning and the second of genius, yet there is no beautiful art in which there is not a mechanical element that can be comprehended by rules and followed accordingly, and in which therefore there must be something [academic] as an essential condition. For [in every art] some purpose must be conceived; otherwise we could not ascribe the product to art at all, and it would be a mere product of chance. But in order to accomplish a purpose, definite rules from which we cannot dispense ourselves are requisite. Now since the originality of the talent constitutes an essential (though not the only) element in the character of genius, shallow heads believe that they cannot better show themselves to be full-blown geniuses than by throwing off the constraint of all rules. They believe, in effect, that one could make a braver show on the back of a wild horse than on the back of a trained animal. Genius can only furnish rich material for products of beautiful art; its execution and its form require talent cultivated in the schools, in order to make such a use of this material as will stand examination by the power of judgement. But it is quite ridiculous for a man to speak and decide like a genius in things which require the most careful investigation by reason. One does not know whether to laugh more at the impostor who spreads such a mist round him that we cannot clearly use our judgement and so [instead] use our imagination the more, or at the public which naïvely imagines that his inability to … comprehend the masterpiece before him arises from new truths crowding in on him in such abundance that details (duly weighed definitions and accurate examination of fundamental propositions) seem but clumsy work. …

Section 50. Of the combination of Taste with Genius in the products of beautiful Art

To ask whether it is more important for the things of beautiful art that genius or taste should be displayed, is the same as to ask whether in it more depends on imagination or on [conceptual] judgement. Now, since in respect of the first an art is rather said to be full of spirit, but only deserves to be called a beautiful art on account of the second; this latter is at least, as its indispensable condition … the most important thing to which one has to look in the judging of art as beautiful art. Abundance and originality of ideas are less necessary to beauty than the accordance of the imagination in its freedom with the conformity to [mental] understanding. For all the abundance of the former produces in lawless freedom nothing but nonsense; on the other hand, judgement is the mental faculty by which it is adjusted to the understanding.

Taste, like the power of judgement in general, is the discipline (or training) of genius; it clips its wings closely, and makes it cultured and polished; but, at the same time, it gives guidance as to where and how far it may extend itself, if it is to remain purposive. And while taste brings clearness and order into the multitude of the thoughts, it makes the ideas susceptible of being permanently and, at the same time, universally assented to, and capable of being followed by others, and of an ever-progressive culture. If, then, in the conflict of these two properties in a product something must be sacrificed, it should be rather on the side of genius; and the judgement, which in the things of beautiful art gives its decision from its own proper principles, will rather sacrifice the freedom and wealth of the imagination than permit anything prejudicial to the understanding.

2.3 Virginia Woolf, Linda Nochlin, and the Idea of Artistic Genius

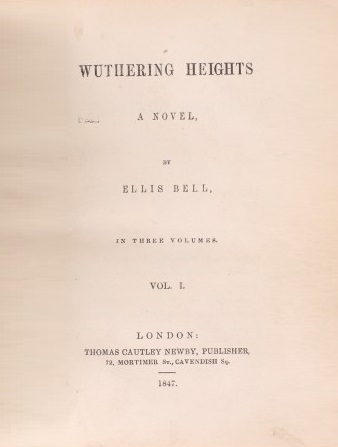

Published in 1929, Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own is one of the most engaging essays ever written on the topic of artistic genius. Today, unfortunately, Woolf’s contribution is generally overshadowed by Linda Nochlin’s essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”, which was published in 1971. (https://www.artnews.com/art-news/retrospective/why-have-there-been-no-great-women-artists-4201/) Woolf was interested in the question of why, until the 20th century, there were only two top-tier women novelists, Jane Austen and Emily Brontë. She identifies only one “great” woman poet, Christina Rossetti. As an art historian, Nochlin takes up a parallel question about the history of visual art. Because of a recent tendency to refer to visual art as art, and to refer to all other art by some other term, The Art Newspaper recently said that “Nochlin did for the history of art what Virginia Woolf did for literary studies” (Chloë Ashby, 2021), as if literature is not art. Take note that in the excerpt provided here, Woolf takes pains to say that Austen and Brontë were artists.

Woolf and Nochlin defend the same point: linking creativity to genius blocks our ability to understand that artistic creativity is not simply — not even mainly — a matter of individual talent. Or, as contemporary artist and musician Brian Eno puts it, “there are no self-made artists.”

Although neither Woolf nor Nochlin mention him, they are challenging Kant’s theory of artistic genius. They want to call attention to systemic barriers that have prevented women from participating in the fine arts, with the side effect that women could not attain the status of “great” artist. While the specific issue is the general absence of women in the Western fine arts, there is a deeper philosophical issue here. Does artistic greatness depend on a special trait in a limited number of individuals, the trait that is generally called “genius”? Or is artistic success primarily due to a combination of support systems (including art training) and social opportunities? Woolf and Nochlin argue that it is primarily the latter. Besides training, artists need a workshop or workspace where they can do their work. However, writers also need personal space, giving Woolf her title: women can’t make art in a household where they have no private space (a room of their own). From Woolf’s perspective, it is no coincidence that neither Jane Austen nor Emily Brontë was married, and so they had fewer responsibilities to family than a married woman who was raising children and running the household. The traditional roles of women as caregivers and homemakers presented huge obstacles to their artistic pursuits.

The fundamental insight of Woolf and Nochlin is that the kind of art that gets produced at any given time or place is both enabled by and limited by prevailing social practices. With this idea in the background, they describe the subculture of art and artists from the Renaissance until the 20th century as subject to patriarchal society, that is, as a set of institutions and practices that routinely blocked women’s equal access to education and property, two necessities for any artist. (Incidentally, barriers to women in literature were not universal. The most important literary work of Japanese culture is an 11th-century novel, The Tale of Genji. It was written by a woman, Murasaki Shikibu, and she is generally credited with inventing the novel as a literary genre. Japanese tradition says that she left the court and secluded herself at a Buddhist temple in order to write it.)

Notice that Woolf’s demand for “a room of one’s own” is partially consistent with Kant’s account of artistic genius. In Section 47 (in the present chapter’s excerpt in Section 2.2), Kant argues that the natural power of genius is not sufficient to make great art. Art is a mode of communication. So, art requires competence in the language used by the person who is communicating. It may seem obvious that a genius who has no knowledge of Japanese is not going to produce masterpieces of Japanese haiku. Kant is making the deeper point that someone who has not studied Elizabethan sonnets is never going to produce something as good as Shakespeare’s poems in sonnet form, no matter how good their grasp of English. No one spontaneously creates a haiku or sonnet, and no one creates good ones without a lot of work studying examples. Sonnets have formal rules, and writing a good sonnet requires a grasp of those rules. The same is true for the plotting of a theater play, film, or novel, or the carving of a marble sculpture. No has ever picked up oil paints and produced a masterpiece on their first attempt. (Think here about Vasari’s discussion of the discovery of da Vinci’s genius in Chapter 1: it emerged some time after da Vinci started his apprenticeship with Andrea del Verrocchio.)

So, we can summarize the debate in this way: the traditional doctrine of genius said that training is needed to unlock genius. Notably, Kant puts genius in conflict with art training in Section 50 of the excerpt above. “Taste,” as a product of education, “clips its wings closely, and makes it cultured.” Woolf and Nochlin are building on this point to suggest something more radical: once we have the foundation of training, it’s not clear that appeal to genius adds anything at all to the explanation of how art gets made. Kant thinks natural genius accounts for originality. Woolf, in contrast, suggests that the “genius” that accounts for originality is no more than an ability to withstand social demands to conform to popular taste. Basically, Woolf says, genius merely means that you tuned out all the critics who want to tell you what to do. To be original, just be yourself. But, Woolf cautions, that’s much harder than it sounds.

Woolf wrote her essay after she was invited to give a talk at a women’s college on the subject of women and literature. She went to the library of the British Museum and noted that there were no books on the subject. (There were, she noted, many books on the subject of women and poverty.) Nochlin wrote her essay after an art buyer asked her about the lack of “great” women artists. Why wasn’t there any visual art available for purchase by women with famous names? When the buyer posed the question to Nochlin in the late 1960s, there was a limited quantity of visual art by women, and it always sold for much lower prices than art by male artists of the same time period. From the perspective of the art buyer, the art market clearly communicated that there were no “great” women artists. Nochlin’s essay aims to answer the art buyer’s question. She does not adopt the stance that the questions is mistaken, but instead acknowledges the insight within the question. Lavinia Fontana and Elisabetta Sirani were successful women artists of the Renaissance, but no one argues that they were “great” or on the same level as Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael Santi, and Michelangelo Buonarroti. (Lavinia Fontana and Elisabetta Sirani are notably absent from Vasari’s Lives.)

In A Room of One’s Own, Woolf makes the parallel point that very few women have been famous novelists. For example, she discusses Mary Ann Evans, who published using a man’s name, George Eliot. Not coincidentally, Jane Austen published anonymously and Emily Brontë used the male name of Ellis Bell. However, Woolf argues that George Eliot is overrated. In fact, Woolf thinks that every famous woman author except Rossetti, Austen, and Brontë is overrated. (Keep in mind that Woolf wrote this in 1928-29). Similarly, Nochlin identifies one woman sculptor and six women painters who achieved some status in the Middle Ages through the late 19th century, and then notes that every single one of them was the daughter of an artist. Each had the good luck to be trained by her father, which also meant access to materials and studio space. Woolf made a parallel point in her earlier essay: how did Shakespeare learn about theater, given that he couldn’t have learned about it in his small home town? He ran away to London. He left home and worked his way up in the theaters of London. If Shakespeare’s sister was just as smart, could she have done the same thing and become an author of plays? No. That was not possible in Elizabethan England.

So, is it a coincidence that there were few “great” women artists and novelists? Did “nature” visit so few women with the magic power of artistic genius? Woolf and Nochlin think not. If we recognize numerous women of talent living today, there’s no reason to think there weren’t just as many in the past. Yet we can’t find them. There must be a social explanation for their absence. For starters, we need to admit that genius operated as a gendered concept. Like “priest” in the Roman Catholic tradition, it was a concept that could only be applied to men. By combining historical associations between creativity, virility, and genius with a more general practice of limiting the roles of women in society, the modern artworld supported the myth that women are inherently less capable of producing great art. And, once the myth emerges in the Renaissance, the ongoing social practice of discrimination gets a justification by appeal to “nature.”

For those who think that Woolf and Nochlin were only talking about historical events, consider the following statistics. Twenty years after Nochlin’s essay was published, her work inspired a study of the art purchases of New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Examining the museum’s recent purchasing of living artists, they found that 95% of the purchases were of work by male artists. Thirty years after that, the situation had not improved very much. Well into the 21st century, it remains the case that museums and collectors do not purchase art by women at the same rate that they purchase art by men, and when they do, they pay far less. A more recent study found that when we exclude the cost of the most expensive art by male artists, such as paintings by da Vinci, art by living women artists sells for about 60% of what men receive.

Excerpt from Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own.

(1929: Public Domain)

But, you may say, we asked you to speak about women and fiction — what has that got to do with a room of one’s own? I will try to explain. … My aunt, Mary Beton, I must tell you, died by a fall from her horse when she was riding out to take the air in Bombay. The news of my legacy reached me one night about the same time that the act was passed that gave votes to women. A solicitor’s letter fell into the post-box and when I opened it I found — that she had left me five hundred pounds [today, about $13,000] a year for ever. Of the two — the vote and the money — the money, I own, seemed infinitely the more important. Before that I had made my living by cadging odd jobs from newspapers, by reporting a donkey show here or a wedding there; I had earned a few pounds by addressing envelopes, reading to old ladies, making artificial flowers, teaching the alphabet to small children in a kindergarten. Such were the chief occupations that were open to women before 1918. I need not, I am afraid, describe in any detail the hardness of the work, for you know perhaps women who have done it; nor the difficulty of living on the money when it was earned, for you may have tried. But what still remains with me as a worse infliction than either was the poison of fear and bitterness which those days bred in me. To begin with, always to be doing work that one did not wish to do, and to do it like a slave, flattering and fawning, not always necessarily perhaps, but it seemed necessary and the stakes were too great to run risks; and then the thought of that one gift which it was death to hide — a small one but dear to the possessor — perishing and with it my self, my soul, — all this became like a rust eating away the bloom of the spring, destroying the tree at its heart. However, as I say, my aunt died; and whenever I change a ten-shilling note a little of that rust and corrosion is rubbed off; fear and bitterness go. Indeed, I thought, slipping the silver into my purse, it is remarkable, remembering the bitterness of those days, what a change of temper a fixed income will bring about. No force in the world can take from me my five hundred pounds. Food, house and clothing are mine for ever. …

and I thought of that old gentleman, who is dead now, but was a bishop, I think, who declared that it was impossible for any woman, past, present, or to come, to have the genius of Shakespeare. He wrote to the papers about it. He also told a lady who applied to him for information that cats do not as a matter of fact go to heaven, though they have, he added, souls of a sort. How much thinking those old gentlemen used to save one! How the borders of ignorance shrank back at their approach! Cats do not go to heaven. Women cannot write the plays of Shakespeare.

Be that as it may, I could not help thinking, as I looked at the works of Shakespeare on the shelf, that the bishop was right at least in this; it would have been impossible, completely and entirely, for any woman to have written the plays of Shakespeare in the age of Shakespeare. Let me imagine, since facts are so hard to come by, what would have happened had Shakespeare had a wonderfully gifted sister, called Judith, let us say. Shakespeare himself went, very probably, — his mother was an heiress — to the grammar school, where he may have learnt Latin — Ovid, Virgil and Horace — and the elements of grammar and logic. He was, it is well known, a wild boy who poached rabbits, perhaps shot a deer, and had, rather sooner than he should have done, to marry a woman in the neighbourhood, who bore him a child rather quicker than was right. That escapade sent him to seek his fortune in London. He had, it seemed, a taste for the theatre; he began by holding horses at the stage door. Very soon he got work in the theatre, became a successful actor, and lived at the hub of the universe, meeting everybody, knowing everybody, practising his art on the boards, exercising his wits in the streets, and even getting access to the palace of the queen. Meanwhile his extraordinarily gifted sister, let us suppose, remained at home. She was as adventurous, as imaginative, as agog to see the world as he was. But she was not sent to school. She had no chance of learning grammar and logic, let alone of reading Horace and Virgil. She picked up a book now and then, one of her brother’s perhaps, and read a few pages. But then her parents came in and told her to mend the stockings or mind the stew and not moon about with books and papers. They would have spoken sharply but kindly, for they were substantial people who knew the conditions of life for a woman and loved their daughter — indeed, more likely than not she was the apple of her father’s eye. Perhaps she scribbled some pages up in an apple loft on the sly, but was careful to hide them or set fire to them. Soon, however, before she was out of her teens, she was to be betrothed to the son of a neighbouring wool-stapler. She cried out that marriage was hateful to her, and for that she was severely beaten by her father. Then he ceased to scold her. He begged her instead not to hurt him, not to shame him in this matter of her marriage. He would give her a chain of beads or a fine petticoat, he said; and there were tears in his eyes. How could she disobey him? How could she break his heart? The force of her own gift alone drove her to it. She made up a small parcel of her belongings, let herself down by a rope one summer’s night and took the road to London. She was not seventeen. The birds that sang in the hedge were not more musical than she was. She had the quickest fancy, a gift like her brother’s, for the tune of words. Like him, she had a taste for the theatre. She stood at the stage door; she wanted to act, she said. Men laughed in her face. The manager — a fat, loose-lipped man — guffawed. He bellowed something about poodles dancing and women acting — no woman, he said, could possibly be an actress. [Note: it was illegal for a woman to appear on stage in Shakespeare’s England.] He hinted — you can imagine what. She could get no training in her craft. Could she even seek her dinner in a tavern or roam the streets at midnight? Yet her genius was for fiction and lusted to feed abundantly upon the lives of men and women and the study of their ways. At last — for she was very young, oddly like Shakespeare the poet in her face, with the same grey eyes and rounded brows — at last Nick Greene the actor-manager took pity on her; she found herself with child by that gentleman and so — who shall measure the heat and violence of the poet’s heart when caught and tangled in a woman’s body? — killed herself one winter’s night and lies buried at some cross-roads where the omnibuses now stop outside the Elephant and Castle [an inn in south London].

That, more or less, is how the story would run, I think, if a woman in Shakespeare’s day had had Shakespeare’s genius. But for my part, I agree with the deceased bishop, if such he was — it is unthinkable that any woman in Shakespeare’s day should have had Shakespeare’s genius. For genius like Shakespeare’s is not born among labouring, uneducated, servile people. It was not born in England among the Saxons and the Britons. It is not born to-day among the working classes. How, then, could it have been born among women whose work began, according to Professor Trevelyan, almost before they were out of the nursery, who were forced to it by their parents and held to it by all the power of law and custom? Yet genius of a sort must have existed among women as it must have existed among the working classes. Now and again an Emily Brontë or a Robert Burns blazes out and proves its presence. But certainly it never got itself on to paper. When, however, one reads of a witch being ducked, of a woman possessed by devils, of a wise woman selling herbs, or even of a very remarkable man who had a mother, then I think we are on the track of a lost novelist, a suppressed poet, of some mute and inglorious Jane Austen, some Emily Brontë who dashed her brains out on the moor or mopped and mowed about the highways crazed with the torture that her gift had put her to. Indeed, I would venture to guess that Anon[ymous], who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman. It was a woman Edward Fitzgerald, I think, suggested who made the ballads and the folk-songs, crooning them to her children, beguiling her spinning with them, or the length of the winter’s night.

This may be true or it may be false — who can say? — but what is true in it, so it seemed to me, reviewing the story of Shakespeare’s sister as I had made it, is that any woman born with a great gift in the sixteenth century would certainly have gone crazed, shot herself, or ended her days in some lonely cottage outside the village, half witch, half wizard, feared and mocked at. For it needs little skill in psychology to be sure that a highly gifted girl who had tried to use her gift for poetry would have been so thwarted and hindered by other people, so tortured and pulled asunder by her own contrary instincts, that she must have lost her health and sanity to a certainty. No girl could have walked to London and stood at a stage door and forced her way into the presence of actor-managers …

And one gathers from this enormous modern literature of confession and self-analysis that to write a work of genius is almost always a feat of prodigious difficulty. Everything is against the likelihood that it will come from the writer’s mind whole and entire. Generally material circumstances are against it. Dogs will bark; people will interrupt; money must be made; health will break down. Further, accentuating all these difficulties and making them harder to bear is the world’s notorious indifference. It does not ask people to write poems and novels and histories; it does not need them. It does not care whether Flaubert finds the right word or whether Carlyle scrupulously verifies this or that fact. Naturally, it will not pay for what it does not want. …

But for women, I thought, looking at the empty shelves, these difficulties were infinitely more formidable. In the first place, to have a room of her own, let alone a quiet room or a sound-proof room, was out of the question, unless her parents were exceptionally rich or very noble, even up to the beginning of the nineteenth century. Since her pin money, which depended on the goodwill of her father, was only enough to keep her clothed, she was debarred from such alleviations as came even to Keats or Tennyson or Carlyle, all poor men, from a walking tour, a little journey to France, from the separate lodging which, even if it were miserable enough, sheltered them from the claims and tyrannies of their families. Such material difficulties were formidable; but much worse were the immaterial. The indifference of the world which Keats and Flaubert and other men of genius have found so hard to bear was in her case not indifference but hostility. The world did not say to her as it said to them, Write if you choose; it makes no difference to me. The world said with a guffaw, Write? What’s the good of your writing?

Thus, I concluded, … it is fairly evident that even in the nineteenth century a woman was not encouraged to be an artist. On the contrary, she was snubbed, slapped, lectured and exhorted. … What genius, what integrity it must have required in face of all that criticism, in the midst of that purely patriarchal society, to hold fast to the thing as they saw it without shrinking. Only Jane Austen did it and Emily Brontë. It is another feather, perhaps the finest, in their caps. They wrote as women write, not as men write. Of all the thousand women who wrote novels then, they alone entirely ignored the perpetual admonitions of the eternal pedagogue — write this, think that. …

I told you in the course of this paper that Shakespeare had a sister; but do not look for her in Sir Sidney Lee’s [A Life of William Shakespeare]. She died young — alas, she never wrote a word. She lies buried where the omnibuses now stop, opposite the Elephant and Castle. Now my belief is that this poet who never wrote a word and was buried at the cross-roads still lives. She lives in you and in me, and in many other women who are not here to-night, for they are washing up the dishes and putting the children to bed. But she lives; for great poets do not die; they are continuing presences; they need only the opportunity to walk among us in the flesh. This opportunity, as I think, it is now coming within your power to give her. For my belief is that if we live another century or so — I am talking of the common life which is the real life and not of the little separate lives which we live as individuals — and have five hundred a year each of us and rooms of our own; if we have the habit of freedom and the courage to write exactly what we think; if we escape a little from the common sitting-room and see human beings not always in their relation to each other but in relation to reality; … if we face the fact, for it is a fact, that there is no arm to cling to, but that we go alone and that our relation is to the world of reality and not only to the world of men and women, then the opportunity will come and the dead poet who was Shakespeare’s sister will put on the body which she has so often laid down. Drawing her life from the lives of the unknown who were her forerunners, as her brother did before her, she will be born. As for her coming without that preparation, without that effort on our part, without that determination that when she is born again she shall find it possible to live and write her poetry, that we cannot expect, for that would be impossible. But I maintain that she would come if we worked for her, and that so to work, even in poverty and obscurity, is worth while.

2.4 Shakespeare’s Sister? What about Shakespeare himself?

If the training of artists reflects larger social values, so do art criticism and critical reception. By the time Woolf is writing, she can simply assume that everyone in her audience knows that Shakespeare was among the greatest writers in all of English literature. However, this positive view of Shakespeare only emerged in the middle and later parts of the 18th century.

Kant was not the first philosopher to discuss Shakespeare’s genius. His evaluation of Shakespeare was mixed, but it was much more positive than that of a slightly older philosopher, David Hume. Born in Scotland 13 years before Kant was born in Prussia, Kant pointed directly to Hume’s philosophy as the spark that inspired his own work. Unlike the average philosopher, Hume was a best-selling author who made a considerable fortune from his writing. Besides several books of essays, he had a great success with his six-volume The History of England. As a Scot, Hume was an outsider, so he was free of the usual biases of English historians. His massive history was the best researched and least politically biased account of English history published up to that time. It quickly became the standard English history, selling steadily for more than a hundred years. An abridged version was used in many British schools.

Hume loved literature and was as well read as anyone of this time. His one major essay concerning art is almost exclusively about literature. His knowledge of literature is reflected throughout The History of England. For example, Hume’s account of the early 17th century includes a segment on English culture and art during the Elizabethan period and the the reign of James I. This segment of the history includes two paragraphs on Shakespeare.

Today, readers are likely to be surprised at Hume’s judgment that Shakespeare is overrated and English theater was harmed by the publication of the plays. Yes, Hume says, Shakespeare’s writing displays genius. But, anticipating what Kant would later say about the need to balance imagination and taste, Hume thinks that Shakespeare proves that genius by itself produces bad art, rather than good art. Shakespeare’s plays are hard to follow and wildly inconsistent: Shakespeare displays a “total ignorance” of genuine artistry. The good parts of Shakespeare’s plays (their “beauties” and “genius”) are noteworthy because the rest of the material is so bad.

Hume begins by saying that if we take the man’s rural background and poor education into account, Shakespeare might be praised for his accomplishment. However, judged against other poets, his work is grossly overrated. In saying that Shakespeare was a “rude genius” who made “rude art,” Hume uses “rude” in its original meaning: something lacking polish and refinement, and likely to appeal to the uneducated masses rather than to the educated class. Hume contrasts Shakespeare with one of his contemporaries, Ben Johnson, and proposes that Johnson was the other extreme: educated but completely lacking in genius. For Hume, that makes Johnson better than Shakespeare: at least Johnson did no harm to later generations. In Hume’s view, Shakespeare only gained a positive reputation because England was a “barbarian” wasteland compared to much of Europe, and so Shakespeare stood out because he lacked competition. Hume had lived in France during two different periods of his life, and regarded French literature and theater as the best produced in modern Europe. In France, Hume is suggesting, Shakespeare could never have made a living as a writer. Where Woolf makes the point that Shakespeare’s sister had no hope of becoming a playwright, Hume anticipated Woolf by making the point that Shakespeare would have failed if he hadn’t been born in a time and place with such low standards for theatrical entertainment.

The point is not that Hume was wrong about Shakespeare. The point, rather, is that Hume represents a relatively common view of his time. Although Hume believed that there are universal standards for good art, he also noted that popularity fluctuates: some artists enjoy a “temporary vogue” and then disappear into well-deserved obscurity. Others gain respect with the passage of time. Shakespeare’s popularity was increasing at the very time that Hume was describing his flaws. More importantly, Hume is making the point that popularity is a social phenomenon, and who gets counted as a great artist is generally an accident of fashion that has little to do with actual merit. As a Scot and thus a “neighbor” to England, Hume seems to be using Shakespeare to introduce a special dig against the English: we can’t trust the English to tell us what’s good and bad about England.

In an ironic twist, Shakespeare’s international popularity after Hume’s lifetime fits Hume’s own criteria for great art as explained in the essay “Of the Standard of Taste” (1757). There, Hume says that with “real genius, the longer his works endure, and the more wide they are spread, the more sincere is the admiration which he meets with.” Shakespeare’s work did spread throughout Europe toward the end of Hume’s life, and his reputation has increased since then. According to Hume’s standard, Shakespeare does turn out to have been a real genius.

Excerpt from David Hume’s History of England, Volume 5 (published 1754)

If Shakespeare be considered as a man, born in a rude age, and educated in the lowest manner, without any instruction, either from the world or from books, he may be regarded as a prodigy. If represented as a poet, capable of furnishing a proper entertainment to a refined or intelligent audience, we must abate much of this eulogy. In his compositions, we regret, that many irregularities, and even absurdities, should so frequently disfigure the animated and passionate scenes intermixed with them; and at the same time, we perhaps admire the more those beauties, on account of their being surrounded with such deformities. A striking peculiarity of sentiment, adapted to a singular character, he frequently hits, as it were by inspiration; but a reasonable propriety of thought he cannot, for any time, uphold. Nervous and picturesque expressions, as well as descriptions, abound in him; but it is in vain we look either for purity or simplicity of diction. His total ignorance of all theatrical art and conduct, however material a defect; yet, as it affects the spectator rather than the reader, we can more easily excuse, than that want of taste which often prevails in his productions, and which gives way, only by intervals, to the irradiations of genius. A great and fertile genius he certainly possessed, and one enriched equally with a tragic and comic vein; but, he ought to be cited as a proof, how dangerous it is to rely on these advantages alone for attaining an excellence in the finer arts. And there may even remain a suspicion, that we over-rate, if possible, the greatness of his genius; in the same manner as bodies often appear more gigantic, on account of their being disproportioned and mishapen. He died in 1616, aged 53 years.

[Ben] Johnson possessed all the learning which was [missing in] Shakespeare, and wanted all the genius of which the other was possessed. Both of them were equally deficient in taste and elegance, in harmony and correctness. A servile copyist of the ancients, Johnson translated into bad English the beautiful passages of the Greek and Roman authors, without accommodating them to the manners of his age and country. His merit has been totally eclipsed by that of Shakespeare, whose rude genius prevailed over the rude art of his contemporary. The English theatre has ever since taken a strong tincture of Shakespeare’s spirit and character; and thence it has proceeded, that the nation has undergone, from all its neighbours, the reproach of barbarism, from which its valuable productions in some other parts of learning would otherwise have exempted it.