1 Art and Representation

Theodore Gracyk

Key Takeaways for Art and Representation

Topic: What was the basic idea that was originally identified to explain the value of fine art?

Until recently, no language had a word or phrase that referenced art as a unified category

The category of fine art emerged as a subset of craft

Representation through imitation was identified as a core requirement of “fine art”

Beauty was identified as another core requirement

Imagination was identified as central to the artistic process

Instrumental music emerged as a problem case: why is it a fine art?

More recently, photography emerged as a problem case

1.1 Introduction to Chapter 1

The basic activities that we now identify as art have existed since our earliest history. Art historians say that art predates human history, that is, it predates the writing systems that record spoken languages. Human writing systems were created less than 5,000 years ago. But decorated objects date back nearly 100,00 years, and wall paintings date back 30,000 years. (See figure 1.1)

In trying to say when prehistoric decorations evolved into prehistoric art, historians use the same criterion that has been used in Western cultures for thousands of years: imitation. Decoration becomes art when it includes recognizable representation. Basically, something is a representation if it shows what some other object is like. To be more precise, one thing is an imitation of a second thing if the first thing is recognizably similar to the second one. An imitation simulates something else by copying or replicating some relevant features of the original. For example, a cook might substitute imitation vanilla for real vanilla in a recipe, or a hunter might use a duck call to imitate the sound of ducks to draw them nearer. In the visual arts, the trick is to “imitate” by making one thing look like another thing.

Using the criterion of imitative representation, the oldest known art sculpture is a figure carved from mammoth ivory that is at least 35,000 years old. The oldest drawing that counts as art is about 27,000 years old. It is a drawing on a cave wall. It consists of a few lines that, together, look like a human face. Music is even older! We have found working flutes (carved from animal bone) that may be as much as 60,000 years old.

However, the issue is complicated once we begin to examine the assumptions that we use when we identify ancient art. Were ancient Homo Sapiens and Neanderthals creating art when they played on their flutes? Did they really make art when they scratched a crude face on a rock? Perhaps it is better to say that they were engaged in activities that were precursors to art, rather than say that they made art.

Why would we hesitate to say that our ancestors made art 30,000 or 100,000 years ago?

Because we can say with great confidence that their activities were not guided by the concept of art.

If we say they were making art, we are using a modern word for ancient practices. The current meaning of the word “art” is different from how the word was used before the early 18th century. In European culture, the earliest similar word was the Greek term, technē (τέχνη, our basis for the modern word “technology”). The ancient Romans used the word ars in place of technē and we get our word “art” from this Latin word. For both the Greeks and the Romans, their word meant the work of an artisan. Secondarily, it meant to the work produced by an artisan, as the product of a skilled handcraft that could be taught and learned. So the category of artist also included bread bakers, shoe makers, even doctors. The mimetic crafts (that is, crafts of imitation) were therefore a subcategory of art that had no special name. The central examples of this subcategory were sculpting and picture making. Ancient peoples also recognized the close affinity between the crafting of these representational physical objects and the imitative activities of the performing arts (e.g., theater performances, story telling, music, dance).

The lesson here is that the modern tendency to draw a sharp distinction between art and craft has a relatively recent origin. Historically, the key step in adopting this distinction was the era we know as the Renaissance. During the 15th and 16th centuries, humanists promoted the view that application of good design was the common feature of successful painting, sculpture, architecture, music, and poetry. Encouraging a revival of techniques borrowed from ancient Greece and Rome, the humanists taught that properly-proportioned design was the shared basis of both beauty and accurate representation. It was also the key to new developments in architecture, so architecture was regarded as closely aligned with the representational arts/crafts.

A renewal of interest in ancient Greek philosophy was an important inspiration for this idea that some “arts” were different from the rest.

In the ancient Greece, the philosophers Plato (c. 428-347 BCE) and Aristotle (384–322 BCE) both recognized and discussed the value of a special subcategory of technē. They were primarily interested in the activity of poets, which led them to speculate about the more general category of imitative representation. This category embraced the visual arts, literature, and performing arts. Yet their language offered them no commonly-accepted name for this broad category of activity, nor for its products. In their time and for the another 2,000 years, talking about our current category of art was like trying to talk about dogs without having the word “dog” in your vocabulary. At best, you might capture this category by talking about “domesticated canines.” This is roughly what anyone before the 18th century had to do when talking about the arts. From the 18th until the 20th century, the norm was to use a two-word phrase, such as the French les beaux-arts or our phrase “the fine arts.” (See Section 1.3 below.)

Discussing ancient Greek theater tragedies, Aristotle emphasized a further distinction within the category of imitative representation. Some imitations are intended to communicate literal truth, while others are not. Visual representations created for scientific and historical documentation attempt to capture and portray reality. “Poets” do something very different: they create fictional worlds for our entertainment and enjoyment. For Aristotle, an illustration in a medical textbook is fundamentally different from a picture of a fictional creature such as a centaur. (See figure 1.2.) Departing from “historical” truth, an image of a centaur would share the function and value that Aristotle’s Poetics assigns to theatrical works. In the key passage excerpted here, Aristotle explains why he thinks people are interested in pictures and stories that do not instruct us about reality.

In summary, we can say that Plato and Aristotle philosophized about art despite having no name for what they were discussing. For Plato was concerned about any craft or technology that involves imitative representation. For Aristotle, it was the narrower category of fictionalized imitation.

Excerpt from Aristotle: Poetics

Translated by S. H. Butcher, 1895; minor amendments by T. Gracyk

Poetry in general seems to have sprung from two causes, each of them lying deep in our nature. First, the instinct of imitation is implanted in us from childhood, one difference between humans and other animals being that humans are the most imitative of living creatures, and through imitation learn our earliest lessons; and no less universal is the pleasure felt in things imitated. We have evidence of this in the facts of experience. Objects which in themselves we view with pain, we delight to contemplate when reproduced with minute fidelity: such as the forms of the most ignoble animals and of dead bodies. The cause of this again is, that to learn gives the liveliest pleasure, not only to philosophers but to everyone … Thus the reason why we enjoy seeing a likeness is, that in contemplating it we find ourselves learning or inferring, and saying perhaps, ‘Ah, that is so-and-so.’ For if you happen not to have seen the original, the pleasure will be due not to the imitation as such, but to the execution, the colouring, or some such other cause.

Imitation, then, is one instinct of our nature. Next, there is the instinct for melody and rhythm, metres being manifestly sections of rhythm. Persons, therefore, starting with this natural gift developed by degrees their special aptitudes, till their rude improvisations gave birth to poetry. …

It is not the function of the poet to relate what has happened, but what may happen, — what is possible according to the law of probability or necessity. The poet and the historian differ not by writing in verse or in prose. The work of Herodotus might be put into verse, and it would still be a species of history, with metre no less than without it. The true difference is that one relates what has happened, the other what may happen. Poetry, therefore, is a more philosophical and a higher thing than history: for poetry tends to express the universal, history the particular. By the universal, I mean how a person of a certain type will on occasion speak or act, according to the law of probability or necessity; and it is this universality at which poetry aims in the names she attaches to the personages. The particular is, for example, what Alcibiades did or suffered. In comedy this is already apparent: for here the poet first constructs the plot on the lines of probability, and then inserts characteristic names — unlike writers of parodies who write about particular individuals. But tragedians still keep to real names, the reason being that what is possible is credible: what has not happened we do not at once feel sure to be possible: but what has happened is manifestly possible: otherwise it would not have happened. Still there are even some tragedies in which there are only one or two well known names, the rest being fictitious.

The historical importance of this excerpt’s third paragraph cannot be over-emphasized. When later theorists attempted to explain why some “fine arts” are different from other arts/crafts, they drew on Aristotle’s Poetics. The special category is not imitative representation in general, but the subset of representation that employs fiction. (See Section 1.3 below.)

Our best guess is that Aristotle’s Poetics is actually a set of lecture notes, or perhaps it is a summary of what he said, recorded by his students. It makes important points without going into detail. However, a crucial idea is advanced in the second paragraph of the excerpt above. Literature, including the subset of theatrical plays, reflects two human instincts. We instinctively take pleasure in all forms of imitation, and Aristotle suggests that this is because human development depends so heavily on our childhood capacity to imitate other people. This instinct persists after childhood, and it furnishes entertainment. At the same time, it is coupled with a second instinct, which is our natural interest in the aesthetic dimension of the world. (For more on this topic, see Chapter 4 of this book.) When an imitation might be of limited or no interest for its subject matter, its “execution” may create interest and give us pleasure. How something is depicted can interest us as much as what is depicted. Music, humor, interesting patterns generally, and the suspense of an unfolding plot can entertain us, and here there is license to depart from our interest in the truth of the material in order to reward our aesthetic instinct. We can also take an interest in the skill displayed by the artist.

In summary, Aristotle divides the arts (i.e., τέχνη or crafts) into the imitative and non-imitative, and then carves out a further distinction within the various methods of imitation. Some are “a species of history.” They aim at “fidelity,” that is, truth. Historians may enhance their work aesthetically, making it more appealing, but a historical poem or a portrait of a famous person remains something quite different from the work of poets. For poets do not aim at fidelity. (For more on this point, see the discussion of Sir Philip Sidney in Chapter 5.) They present the world as it might be, not how it is. Thus, Greek discussions of imitative practices set the stage for the Renaissance interest in a special set of skilled practices (arts) that produce beautiful creative fictions. In the 18th century, these practices would be given a special title: the fine arts.

1.2 Vasari’s Life of Leonardo da Vinci

The ancient Greek emphasis on imitation as the core feature of several arts was revived during the 15th and 16th centuries, the period of European history we call the Renaissance. This period of European history is notable for the revival of interest in ancient Greece and Rome, contributing knowledge, techniques, and inspiration to science and the various arts.

In Renaissance Italy, theorists grouped three arts together in the category of visual design. These were painting, sculpture, and architecture. Here, we have two arts of imitation and one “practical” art. This grouping of three is the organizing principle of the book that is generally recognized as the first work of art history, Giorgio Vasari’s The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. (See figure 1.3.) This 16th-century book is often translated as The Lives of the Artists, but that is a highly misleading translation. Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael were discussed as great painters. People of that time would see no praise or positive implication in describing them as “artists” (artisans, i.e., skilled at making things with their hands). In fact, when da Vinci was seeking employment with the Duke of Milan, he described himself as an engineer. He also promoted himself as an architect and as someone who could forge bronze sculpture. But, in keeping with his times, he never called himself an “artist” or any equivalent word. The closest he comes to it is when he writes that he is highly skilled at making paintings.

As seen in the following selection from Vasari’s Lives, a successful painter was someone who could create a realistic imitation of whatever was pictured. Vasari stressed that the best painters were “men of genius.” For Vasari, this meant that the skill was based on a natural ability that some people have in a high degree. He adopted this from ancient Roman writings. In relation to the visual arts, this innate skill was, in part, the ability to apply one’s active imagination to the problem of what to show and what not to show.

Although the basic techniques of drawing and painting could be taught and acquired through practice, Vasari does not think the same about imagination’s contribution to picture making. The need for imagination is an assumption embedded in the Latin language. The assumption made its way into English, which adopted terminology from Latin. Originally, “imagination” meant our ability to form mental images. (Surprisingly, nearly 5% of all people lack this common ability.) Renaissance theorists stressed that the image that the painter produces on a wall, board, or canvas was guided by an image in the artist’s mind, that is, in the image-producing power of the imagination. In other words, they thought that the skill of making a realistic picture depends on the natural talent of forming and holding images in one’s imagination. Vasari contends that Leonardo da Vinci was the genius who possessed this talent in the highest degree, as evidenced by his talent for observing someone in the street and then going home and making an accurate portrait of them from memory.

Giorgio Vasari: Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects

Excerpt from “Life of Leonardo da Vinci” (1452‐1519), translated by E.L. Seely

… Marvelous and divine, indeed, was Leonardo the son of Ser Piero da Vinci. In erudition and letters he would have distinguished himself, if he had not been variable and unstable. For he set himself to learn many things, and when he had begun them gave them up. In arithmetic, during the few months that he applied himself to it, he made such progress that he often perplexed his master by the doubts and difficulties that he propounded. He gave some time to the study of music, and learnt to play on the lute, improvising songs most divinely. But though he applied himself to such various subjects, he never laid aside drawing and modeling in relief, to which his fancy inclined him more than to anything else; which [his father] perceiving, he took some of his drawings one day and carried them to Andrea del Verrocchio, with whom he was in close friendship, and prayed him to say whether he thought, if Leonardo gave himself up to drawing, he would succeed. Andrea was astounded at the great beginning Leonardo had made, and urged [the senior da Vinci] to make [his son] apply himself to it. So he arranged with Leonardo that he was to go to Andreaʹs workshop, which Leonardo did very willingly, and set himself to practice every art in which design has a part. For he had such a marvelous mind that, besides being a good geometrician, he worked at modeling (making while a boy some laughing womenʹs heads, and some heads of children which seem to have come from a masterʹs hand), and also made many designs for architecture; and he was the first, while he was still quite young, to discuss the question of making a channel for the river Arno from Pisa to Florence. He made models of mills and presses, and machines to be worked by water, and designs for tunneling through mountains, and levers and cranes for raising great weights, so that it seemed that his brain never ceased inventing; and many of these drawings are still scattered about. Among them was one drawn for some of the citizens when governing Florence, to show how it would be possible to lift up the church of [Saint] Giovanni, and put steps under it without throwing it down; and he supported his scheme with such strong reasons as made it appear possible, though as soon as he was gone every one felt in his mind how impossible it really was. …

While, as we have said, he was studying [in the workshop of] Andrea del Verrocchio, the latter was painting a picture of [Saint] John baptizing Christ. Leonardo worked upon an angel who was holding the clothes, and although he was so young, he managed it so well that Leonardoʹs angel was better than Andreaʹs figures, which was the cause of Andreaʹs never touching colors again, being angry that a boy should know more than he.

There is a story that his father, Ser Piero, being at his country house, was asked by one of the country people to get a round piece of wood, which he had cut from a fig tree, painted for him in Florence, which he very willingly undertook to do, as the man was skilled in catching birds and fishing, and was very serviceable to Ser Piero in these sports. So having it brought to Florence without telling Leonardo where it came from, he asked him to paint something upon it. Leonardo, finding it crooked and rough, straightened it by means of fire, and gave it to a turner that it might be made smooth and even. Then having prepared it for painting, he began to think what he could paint upon it that would frighten every one that saw it, having the effect of the head of Medusa. So he brought for this purpose to his room, which no one entered but himself, lizards, grasshoppers, serpents, butterflies, locusts, bats, and other strange animals of the kind, and from them all he produced a great animal so horrible and fearful that it seemed to poison the air with its fiery breath. This he represented coming out of some dark broken rocks, with venom issuing from its open jaws, fire from its eyes, and smoke from its nostrils, a monstrous and horrible thing indeed. And he suffered much in doing it, for the smell in the room of these dead animals was very bad, though Leonardo did not feel it from the love he bore to [painting]. When the work was finished, Leonardo told his father that he could send for it when he liked. And Ser Piero going one morning to the room for it, when he knocked at the door, Leonardo opened it, and telling him to wait a little, turned back into the room, placed the picture in the light, and arranged the window so as to darken the room a little, and then brought him in to see it. Ser Piero at the first sight started back, not perceiving that the creature that he saw was painted, and was turning to go, when Leonardo stopped him saying, ʺThe work answers the purpose for which it was made. Take it then, for that was the effect I wanted to produce.ʺ The thing seemed marvelous to Ser Piero, and he praised greatly Leonardoʹs whimsical idea. And secretly buying from a merchant another circular piece of wood, painted with a heart pierced with a dart, he gave it to the countryman, who remained grateful to him as long as he lived. But Leonardoʹs Ser Piero sold to some merchants in Florence for a hundred ducats, and it soon came into the hands of the Duke of Milan, who bought it of them for three hundred ducats. …

Leonardo was so pleased whenever he saw a strange head or beard or hair of unusual appearance that he would follow such a person a whole day, and so learn him by heart, that when he reached home he could draw him as if he were present. There are many of these heads to be seen, both of men and women, such as the head of Americo Vespucci, which is the head of an old man most beautifully drawn in chalk; and also of Scaramuccia, captain of the gypsies.

When Giovan Galeazzo, Duke of Milan, was dead, and Lodovico Sforza became duke in the year 1494, Leonardo was brought to Milan to play the lute before him, in which he greatly delighted. Leonardo brought an instrument which he had made himself, a new and strange thing made mostly of silver, in the form of a horseʹs head, that the tube might be larger and the sound more sonorous, by which he surpassed all the other musicians who were assembled there. Besides, he was the best improviser of his time. The duke, hearing his marvelous discourse, became enamored of his talents to an incredible degree, and prayed him to paint an altarpiece of the Nativity, which he sent to the emperor.

He also painted in Milan for the friars of [Saint] Domenic, at St. Maria delle Grazie, a Last Supper, a thing most beautiful and marvelous. He gave to the heads of the apostles great majesty and beauty, but left that of Christ imperfect, not thinking it possible to give that celestial divinity which is required for the representation of Christ. The work, finished after this sort, has always been held by the Milanese in the greatest veneration, and by strangers also, because Leonardo imagined, and has succeeded in expressing, the desire that has entered the minds of the apostles to know who is betraying their Master. So in the face of each one may be seen love, fear, indignation, or grief at not being able to understand the meaning of Christ; and this excites no less astonishment than the obstinate hatred and treachery to be seen in Judas. Besides this, every lesser part of the work shows an incredible diligence; even in the tablecloth the weaverʹs work is imitated in a way that could not be better in the thing itself.

It is said that the prior of the place was very importunate in urging Leonardo to finish the work, it seeming strange to him to see Leonardo standing half a day lost in thought; and he would have liked him never to have put down his pencil, as if it were a work like digging the garden. And this not being enough, he complained to the duke, and was so hot about it that he was constrained to send for Leonardo and urge him to the work. Leonardo, knowing the prince to be acute and intelligent, was ready to discuss the matter with him, which he would not do with the prior. He reasoned about [the art of painting], and showed him that men of genius may be working when they seem to be doing the least, working out inventions in their minds, and forming those perfect ideas which afterwards they express with their hands. He added that he still had two heads to do; that of Christ, which he would not seek for in the world, and which he could not hope that his imagination would be able to conceive of such beauty and celestial grace as was fit for the incarnate divinity. Besides this, that of Judas was wanting, which he was considering, not thinking himself capable of imagining a form to express the face of him who after receiving so many benefits had a soul so evil that he was resolved to betray his Lord and the creator of the world; but this second he was looking for, and if he could find no better there was always the head of this importunate and foolish prior. This moved the duke marvelously to laughter, and he said he was a thousand times right. So the poor prior, quite confused, left off urging him and left him alone, and Leonardo finished Judasʹs head, which is a true portrait of treachery and cruelty. But that of Christ, as we have said, he left imperfect. The excellence of this picture, both in composition and incomparable finish of execution, made the King of France desire to carry it into his kingdom, and he tried every way to find architects who could bring it safely, not considering the expense, so much he desired to have it. But as it was painted on the wall his Majesty could not have his will, and it with the Milanese refectory.

While he was working at Supper, he painted Lodovico with his eldest son, Massimiliano, and on the other side the Duchess Beatrice with Francesco her other son, both afterwards Dukes of Milan. While he was employed upon this work he proposed to the duke that he should make a bronze equestrian statue of marvelous size to perpetuate the memory of the Duke [Francesco Sforza]. He began it, but made the model of such a size that it could never be completed. There are some who say that Leonardo began it so large because he did not mean to finish it, as with many of his other things. But in truth his mind, being so surpassingly great, was often brought to a stand because it was too adventuresome, and the cause of his leaving so many things imperfect was his search for excellence after excellence, and perfection after perfection. And those who saw the clay model that Leonardo made, said they had never seen anything more beautiful or more superb, and this was in existence until the French came to Milan with Louis, King of France, when they broke it to pieces. There was also a small model in wax, which is lost, which was considered perfect, and a book of the anatomy of the horse which he made in his studies. … Afterwards with greater care he gave himself to the study of human anatomy, aided by, and in his turn aiding, Marc Antonio della Torre who was one of the first to shed light upon anatomy, which up to that time had been lost in the shades of ignorance. In this he was much helped by Leonardo, who made a book with drawings in red chalk, outlined with a pen, of the bones and muscles which he had dissected with his own hand. There are also some writings of Leonardo written backward with the left hand, treating of painting and methods of drawing and coloring. …

1.3 The Modern System of the Arts

The view that art is something other than skilled craft became a fixture of modern thinking during the historical period known as the Enlightenment. Intellectually, this time period saw the development of the modern sciences. A related intellectual movement was the rise of encyclopedic classification. Scientific thinking included the goal of classifying everything according to its essential features, including human activities.

This mania for classification produced the first book that attempted to define the set of human activities that we now commonly call the arts. It was The Fine Arts Reduced to a Single Principle, published in 1746 by French author Charles Batteux. (See figure 1.6.) This book is literally the first systematic attempt to define art in the modern sense of the term. At the time, the fine arts included music, poetry, painting, sculpture, and dance. Although we cannot confirm that he was familiar with Vasari, Batteux includes architecture as straddling fine art and applied science.

Batteux spells out some assumptions that had been implicit in Vasari’s book. As opposed to the practical arts such as farming and medicine, the fine arts are representational activities of a special kind. In French, “Les beaux arts” are literally the beautiful arts. A parallel phrase was adopted in Germany: Schöne Kunst. In England, early translators used the phrases “polite arts” and “the finer arts,” the second of which was soon simplified to the fine arts.

Batteux’s definition is functional. That is, it seeks a definition by assigning a goal to artistic activity. According to Battuex, the arts should not be understood as a subset of craft, but rather as a subset of entertainment. While this proposal might seem surprising, it derives from Aristotle, who proposed some 2,000 years earlier that the primary aim of producing representational art (including story telling) is the pleasure that “imitation” (mimesis) naturally gives us. Batteux cites Aristotle’s Poetics for an explanation of how artistic representation of an event differs from a historical account of the same event. Artists have a license to invent that historians are denied.

Generalizing from Aristotle’s remarks on ancient Greek theater, Batteux proposes that something belongs to the fine arts only if (1) it involves imitative representation and (2) the aim is to give people pleasure in seeing or hearing it. But, unlike the pleasure of a tasty snack or a dip in the lake on a hot summer’s day, the pleasure of art is mental instead of physical. The arts please us because they are beautiful representations. To achieve a beautiful representation, an artist must engage in imaginative activity that achieves a recognition of the ideal nature of whatever is depicted. An idealized representation is shared with an audience to entertain them.

However, one cannot find the ideal version of anything if one examines only one example. An artist does not succeed through strictly accurate representation, but rather through imaginative departure from observed nature. Specifically, the successful artist must synthesize many examples, and this synthesis occurs in imagination. In this way, all art requires invention and fabrication. Batteux offers the example of Molière’s play, The Misanthrope (1666). Molière’s play does not succeed because he knew a misanthrope (that is, someone who hates all other people) and wrote a play about that specific person. The play succeeds because the central character is a composite that brings together the words and actions of multiple people, so that the composite reveals the essential or ideal traits that misanthropes possess.

Because successful artworks are composites assembled in the artist’s imagination, artists create fictions in order to say something about reality. The most pleasing imitations, Batteux proposes, are “more perfect” than any one real example can ever be. In a passage that sounds very much like the excerpt from Aristotle’s Poetics provided earlier in this chapter, Batteux says that the function of art is to please us by revealing truths through the presentation of fictions. (See Chapter 5 for subsequent theorizing about this puzzling claim.)

Employing this complex definition, Batteux identifies the fine arts as music, poetry (i.e., both theater and literature), painting, sculpture, and dance. If the inclusion of dance puzzles you, do not think about dancing to music at a party but think of an audience viewing dance presented in a theater performance, such as a ballet performance of The Nutcracker or Swan Lake. (See figure 1.7.) Architecture is a borderline case: part engineering, part art.

It is easy to misunderstand what Batteux means when he says that the fine arts please an audience by imitating “nature.” This does not mean imitating natural scenes, landscapes, and so on. It means that things in the world around us fit into distinctive categories or natures. This is what we mean today when we say that there is such a thing as human nature, as in the idea that it is human nature (but not, presumably the nature of trees and rocks) to experience empathy, jealousy, pride, greed, and so on. However, different people have different emotions in varying degrees. Consider another play by Molière, The Miser (1668). (Batteux seems to reference this play in passing when he mentions the task of representing a miser.) A miser has an imbalance in having one of the basic human qualities (greed) in an excessive degree. Therefore an artistic portrait of a greedy miser will entertain and please an audience by discovering and showing the essential prototype of greed. In a view that stretches back to the ancient Greeks, Batteux assumes that a representation of the basic prototypes of each kind of thing will be beautiful. Thus, fine art will involve the imitation of beautiful nature. In this way, even ugly things turn beautiful in art.

Batteux’s description of artistic genius is a refinement of Renaissance thought. For Batteux, genius is a natural talent for discovery and synthesis, and only secondarily a talent for making paintings, sculpture, and so on. Genius employs imagination to locate natural prototypes, and then these prototypes are replicated in an artistic medium.

An obvious problem with this theory is that it does not seem to describe instrumental music. In the case of music without words, how does a piece of music imitate anything? What aspects of nature does it explore and represent? Batteux’s answer was common in his time. Music explores human nature by displaying and exploring the flow of human passion (i.e., emotions). His discussion of how composers create emotionally-charged music provides additional details to his account of artistic genius. This is found in his discussion of artistic enthusiasm, which Batteux relates to mental forcefulness. To arrive at a representation, the artist is required to forget all their real-world concerns and forcefully imagine the scene or scenario they wish to imitate. The artist must imagine it with enough force that it seems almost real, causing the artist to experience strong emotions about it. The flow and dynamic of emotion that the composer experiences during a period of imaginative enthusiasm is the composer’s prototype for the music. Instrumental music is different from the other arts in focusing on emotion as its primary object of imitation. (This doctrine becomes widely accepted until there is a backlash against it in the 19th century. See Chapter 4, Section 4.2.)

Speaking metaphorically by employing Greek mythology, Batteux says that “the god” of art must come to aid of artists, permitting them to sustain their enthusiasm. But he then says we must cut out this “allegorical splendor” (i.e., the metaphorical language) of appealing to muses and gods. In keeping with Enlightenment thought, he wants us to ask ourselves what’s really going on when we talk this way. Batteux then endorses the doctrine that the best artists are simply “privileged souls” in terms of their imaginations. The essence of artistic genius is something one must be born with, not something one can learn or acquire.

Selections from Charles Batteux, The fine arts, or, A dissertation on poetry painting, music, architecture, and eloquence.

Anonymous English Translation: 1749, minor changes by T. Gracyk in relation to 2nd edition French text

Chapter I

The arts may be divided into three kinds based on their function. The first have for their object the necessities of our species, whom nature seems to abandon, helpless, as soon as we are born: exposed to cold, hunger, and a thousand evils, nature has ordained that the cure and prevention for these threats should be solved by hard work and creative problem solving. From this we have the mechanical arts.

Those of the second kind have pleasure for their goal. These must have taken their rise when people began to be blessed with the sweets of tranquility and plenty. They are called the fine arts; such are music, poetry, painting, sculpture, and the art of gesture, i.e., dancing.

The third kind are those which mix together the aims of utility and pleasure: such are eloquence and architecture. Necessity first produced them; taste gave them their perfections; and they hold a middle place between the other two.

The arts of the first kind use and modify nature, such as she is, solely for practical use. Those of the third kind make use of nature but modify what is done to also give us pleasure. The fine arts do not [directly] modify nature itself but instead imitate her, each of the fine arts doing so in its own way. Therefore, nature alone is the object of all arts; it is she that occasions all our wants, and furnishes all our pleasures.

[In this book] we shall discuss only the fine arts, that is to say, of those whose main goal is to produce pleasure; and, to be the better acquainted with them, let us go back to the cause that produced them.

People made arts, and it was for themselves they made them. Unsatisfied with the limited pleasures offered by raw nature, and finding themselves well off to an extent that they could pursue pleasure, people had recourse to their genius and created a new order of ideas and emotions, awakening their minds and stimulating their taste. But what could this genius do if it limits itself to what is there in nature? The problem is compounded when genius aims to please people who are also confined by natural limitations. To succeed, efforts must have been made to choose the most beautiful parts of nature, [combining things] to form one exquisite whole which should be more perfect than anything in nature itself, without ceasing, however, to [have a basis in] nature. This is the principle upon which the fundamental plan of all arts must necessarily have been built, and which all the great artists have followed in every age of the world.

Whence we may conclude, first, that genius, which is the father of arts, ought to imitate nature. Secondly, that nature should not be imitated such as she is. Thirdly, that taste, for which arts are made, and which is the judge [of art], is satisfied whenever nature is well chosen and well imitated by the arts. Therefore, all our rules should tend to establish that the fine arts are the imitation of (what we may call) beautiful nature.

The word “imitation” implies the ideas of two distinct things. First, the prototype, or that which contains the touches to be imitated. Secondly, the copy which represents them. Nature (that is to say, all that is, or that we easily conceive as possible) is the prototype or model of arts. An industrious imitator must have his eyes always fixed upon her, and be always considering her. And why? Because nature contains all the plans of well-integrated works, and the designs of every ornament that can please us. Arts do not create their own rules. The rules are independent of human caprice, and invariably derive from the example of nature.

Chapter II

What is the function of the fine arts? It is to take features found in nature, and to present them in artifacts. It is thus that the statue maker’s cutting tool shows or produces a hero in a block of marble. The painter, by his light and shade, makes visible objects seem to project from the canvas. The musician, by artificial sounds, makes the storm roar while the concert room is peacefully quiet; and the poet’s invention, and by the harmony of his verses, fills our minds with imagined images, and our hearts with fabricated emotions, often more charming than if they were true and natural. Whence I conclude, that arts are only imitations, resemblances which are not really nature, but seem to be so; and that thus the matter of the fine arts is not the true, but only the probable. This conclusion is important enough to be explained and proved immediately by application to each of the arts.

Painting is an imitation of visible objects. It has nothing that is real, nothing that is true, and its perfections depend only upon its resemblance to reality.

Music and dancing may very well regulate the tones and gestures of an orator in the pulpit, or of a citizen who tells a story in conversation; but it is not properly in those respects that they are called arts. They may also wander, on the one hand going into little caprices where the sounds bounce against each other without a coherent design; on the other hand into fantastic leaps and jumps: but neither the one nor the other are then in following the rules of art. To be what they ought to be, they must return to imitation, and provide a portrait of the human passions.

Fiction, finally, is the very life and soul of poetry [and literature]. In the art of storytelling, the wolf bears all the characters of man powerful and unjust; the lamb those of innocence oppressed. Pastoral poetry offers us poetical shepherds, but these shepherds are [fictionalized] resemblances or images. Comedy presents the picture of a perfect miser by capturing the characteristics of real avarice.

Tragedy is not properly poetry but it is similar by being a kind of imitation. [Someone writes how] Caesar has had a quarrel with Pompey. This text is not poetry, but history. But if actions, discourses, intrigues, are invented from the ideas which history gives us of the characters and fortune of Caesar and Pompey, this is what may be called poetry, because it is the work of genius and art.

The epic, too, is only a recital of probable actions, represented with all the characters of existence. Juno and Aeneas neither said nor did what Virgil attributes to them; but they might have said or done it, and that is enough for poetry. It is one long fiction featuring characteristics of truth.

In this way every art, with respect to what is truly artificial in it, is only an imaginary thing, something illusory, copied and imitated from true ones. It is for this reason that art is always put in opposition to nature, so that we hear it everywhere said, that we must imitate nature and that art is perfect when the representation is accurate; and, in short, that all master-pieces of art are those where nature is so well imitated that they seem nature herself.

And this [practice of] imitation, for which we have a natural disposition and which instructs and governs us, is one of the principal springs that produces the arts. The mind exercises itself in comparing the model with the picture; and the judgment it gives is so much the more agreeable, as it is a proof of our knowledge and penetration.

Genius and taste have so close a connection in arts, that there are cases where they cannot be thought about without mixing the one with the other, nor separated without misrepresenting their functions. This is the case here, where it is impossible to say what a genius ought to do in imitating nature, without supposing taste to be his guide.

Aristotle compares poetry with history; their difference, according to him, is not in the form, or style, but in the very nature of the things. But how so? History only paints what has actually happened, poetry what can happen [i.e., what is possible]. One is tied down to truth, so historians creates neither actions nor actors. The artist regards nothing but the probable, so art invents; it designs at its own pleasure, and paints only from the brain. History gives examples, such as they are, often imperfect. The poet gives them such as they ought to be. And it is for this reason, according to Aristotle, that poetry is a much more instructive lesson than history.

Upon this principle we must conclude, that if arts are imitations of nature, they ought to be bright and lively imitations, that do not copy things exactly, but having chosen objects, represents them with all the perfections they are capable of, always taking care, that in such compositions the parts have a proper relation to one another; otherwise, the whole may be absurd, while every single part taken separately remains beautiful. In a word, fine art consists of imitations where nature is seen, not such as she really is, but such as she may be, and such as may be conceived in the mind.

What did Zeuxis do when about to paint a perfect beauty? Did he draw the picture of a particular beautiful woman? No, he collected the separate features of several beauties who were at that time living. Then he formed in his mind an idea that resulted from all these features united; and this idea was the prototype or model of his picture, which was probable and poetical in the whole, and was true and historical only in the parts taken separately. And this is what every painter does, when he represents the persons he paints with more beauty and grace than they really have. This is an example given to all artists: this is the road they ought to take, and it is the practice of every great master without exception.

When the playwright Molière wanted to portray a misanthrope, he did not search for an original, of which his character should be an exact copy; had he so done he had made but a picture, a history; he had then instructed but by halves: but he collected every characteristic, every stroke of a gloomy temper, that he could observe amongst men. To this he added all that the strength of his own genius could furnish him of the same kind; and from all these hints, well connected, and well laid out, he drew a single character, which was not the representation of the true, but of the probable. His comedy was not the history of Alceste, but his picture of Alceste was the history of misanthropy taken in general. And hence he has given much better instruction than as scrupulous historian could possibly have done by only relating some strictly true facts about a real misanthrope.

It was a saying among the ancients, that such a thing is beautiful as a statue. …

These examples are sufficient to give a clear and distinct idea of what we call beautiful nature in fine art. It does not consist in the truth about the way nature does exist, but that truth which may exist, beautiful truth; which is represented as if it really existed, and with all the perfections it can receive.

The quality of the object makes no difference. [Horrible things become beautiful in art.] Let it be a Hydra or a miser, a hypocrite or a Nero, if they are well drawn, and represented with all the fine touches that belong to them, we still say, that beautiful nature is there painted. It matters not whether it be the [ugly] Furies or the [beautiful] Graces.

This does not, however, prevent truth and reality being made use of by the fine arts. It is thus that the Muses express themselves in Hesiod:

It is our task to speak the truth in language plain,

Or give the appearance of truth to what we pretend.

If a historical fact were found so well worked up as to be fit to serve for a plan to a poem or a piece of painting, poetry and painting too would immediately employ it as such, and would on the other hand make use of their privileges, in inventing circumstances, contrasts, situations, etc. When Charles LeBrun painted the battles of Alexander, he found in history the facts, the actors, and the scene of action; but, notwithstanding this, what noble invention is found in the painting! What a glow of poetry in his work! The dispositions, attitudes, expressions of passions, all these remained for his own genius to create; there art built upon a foundation of truth, and this truth ought to be so elegantly mixed with the artist’s own invention, as to form one unified whole.

The most creative artists, however, do not always feel the presence of the Muses. Shakespeare, who was born a poet, produced shamefully bad work for the stage. [Editorial note: The previous sentence and the later Shakespeare examples were added by the English translator.] …

And yet there are certain happy moments for artistic genius, when the soul, as if filled with fire divine, takes in all nature, and spreads upon all objects that heavenly life which animates them, those engaging strokes which warm and ravish us. This situation of the soul is called enthusiasm, a word which all the world understands, and which hardly anyone has defined. The ideas which most authors give of it, seem rather to come from an enraptured imagination, filled with enthusiasm itself, than from a head that thinks and reflects coolly. At one time it is a celestial vision, a divine influence, a prophetic spirit; at another it is an intoxication, an ecstasy, a joy mixed with trouble, and admiration in the presence of the divine.

[Thinking critically about descriptions like this,] do they aim to elevate the fine arts by use of exaggeration, and to hide from the profane the mysteries of the Muses?

However, those who want to really understand genius will despise this allegoric splendor because it blinds them. Let them consider enthusiasm as a philosopher considers great men, without any regard to the pompous words that obscure those ideas. …

Privileged souls receive strongly the impression of those things they conceive, and never fail to reproduce them, adorned with new beauty, force, and elegance. This is the source and principle of enthusiasm. We may already perceive what must be the effect with regard to the arts which imitate nature. Let us call back the example of Zeuxis. Nature has in her treasures all those images of which the most beautiful imitations can be composed: they are like sketches in the painters tablets. The artist, who is essentially an observer, views them, takes them from the heap, and assembles them. He composes from these a complete whole, of which he conceives an idea that fills him, and is at the same time both bright and lively. Presently his fire glows at the sight of the object; he forgets himself; his soul passes into the thing being created; he is by turns Caesar, Brutus, Macbeth, and Romeo. It is in these transports that Homer sees the chariots and courses of the Gods, that Virgil hears the horrible screams of Phlegyas in the shadows of hell; and that each of them discovers things which are nowhere to be found, and which notwithstanding are true. …

It is for the same reason that enthusiasm is necessary for painters and musicians. They ought to forget their situation, and to fancy [i.e., imagine] themselves in the midst of those things they would represent. If they would paint a battle, they transport themselves in the same manner as the poet, into the middle of the fight: they hear the clash-of arms, the groans of the dying; they see rage, havoc, and blood. They rouse their own imaginations, until they find themselves moved, distressed, frighted. …

It is why Cicero says, “a poet’s inspiration is a strong mind stirred by a divine spirit.” This is poetic rage; this is enthusiasm; this is the god that the poet invokes in the epic, that inspires the hero in tragedy, that transforms himself into the simple citizen in comedy, into the shepherd in pastoral, that gives reason and speech to animals in the apologue or fable. In short, the god that makes true painters, musicians, and poets.

1.4 Some (but not all) photography is defended as fine art

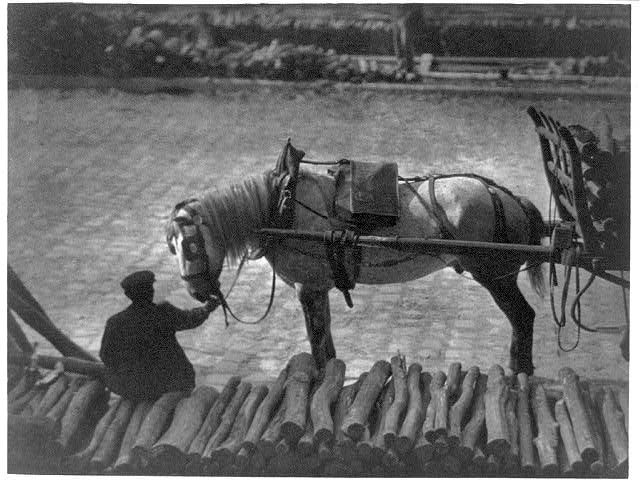

Despite many arguments and disagreements in the centuries that followed, the core ideas of Batteux’s theory were generally accepted until the early 20th century. When photography appeared in the 19th century, it seemed that photography could not be a fine art. After all, in the early years a photograph was a direct impression of light reflected from objects, and a photograph did nothing but make a fixed impression of that light. The image was created by a machine, not a human, and so there is a purely mechanical relationship between a photograph and whatever it shows. Therefore, there could be no “genius” for photography. Contrary to the long line of influence that runs from Aristotle through Batteux and into the 19th century, imaginative fiction was a necessary ingredient of art. How can this requirement be satisfied by a photograph that necessarily shows things as they are? (See figure 1.9.)

Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) was an important photographer, art dealer, and writer. He was concerned with the issue just explained. He believed in artistic genius, and he believed that high levels of imagination distinguish art from other human activities. How, then, to justify machine-generated images as genuine fine art? He was also concerned with the question of how to distinguish art photography from the millions of snap-shots taken every day by people who do not make art when they use a camera. “Art” does not seem to be an important pursuit if everyone who takes photographs counts as an artist. How is there art involved if picture taking requires no training or skill? In brief, Stieglitz proposes that training and skill are less important than the urge to convey one’s personal inner vision.

Stieglitz assumes that a “true photographer” must have the same skill set as a good painter. A work of art must be the “expression” of the artist’s mental state, rather than a simple recording of the world as seen around us. Art represents an artist’s “impressions” of the world. Just as painting is more a “mental process” than a physical technique, art photography is, too. Therefore, technical skills cannot make someone a photographer. Technical training might allow a “purely technical” photographer to earn a living with a camera, but such a person is simply making pictures, not art. And the average “ignorant” amateur who uses a camera doesn’t make art, either.

What is it that the average person, and even some professional photographers, lack? Ideas and vision, says Stieglitz. The average person wants to take pictures that show what things look like. In contrast, an artist wants to reveal a “vision” of the world — a vision infused with the photographer’s emotions and ideas. The artist has an emotionally-charged inner vision of reality. Therefore, the same is required for art photography. (Stieglitz does not reference imagination, but his account of his own artistic process aligns neatly with earlier doctrines of imaginative vision.) Other arts can create a fictional representation that represents that vision, but the photographer has to look at the visible world and find situations and moments that will correspond with the photographer’s personal vision. Then, and only then, is photography an art. Because artistry stems from mental vision, the key component that makes photography an art cannot be taught or learned. You’re either born a visionary, in which case even a technically bad photograph might be a great work of art, or you cannot make art at all. Someone who is born a visionary can improve their technique with practice, including the ability to manipulate the image during the processing stage in order to better give more forceful expression to the motivating inner vision. But Stieglitz warns that this increase in technical skill might also reduce the expressive power of one’s art.

Alfred Stieglitz, “Pictorial Photography”

Scribner’s Magazine, 1899

About ten years ago the movement toward pictorial photography evolved itself out of the confusion in which photography had been born, and took a definite shape in which it could be pursued as such by those who loved art and sought some medium other than brush or pencil through which to give expression to their ideas. Before that time pictorial photography, as the term was then understood, was looked upon as the bastard of science and art, hampered and held back by the one, denied and ridiculed by the other. It must not be thought from this statement that no really artistic photographic work had been done, for that would be a misconception; but the point is that though some excellent pictures had been produced previously, there was no organized movement recognized as such.

Let me here call attention to one of the most universally popular mistakes that have to do with photography — that of classing supposedly excellent work as professional, and using the term amateur to convey the idea of immature productions and to excuse atrociously poor photographs. As a matter of fact nearly all the greatest work is being, and has always been done, by those who are following photography for the love of it, and not merely for financial reasons. As the name implies, an amateur is one who works for love; and viewed in this light the incorrectness of the popular classification is readily apparent.

Pictures, even extremely poor ones, have invariably some measure of attraction. The savage knows no other way to perpetuate the history of his race; the most highly civilized has selected this method as being the most quickly and generally comprehensible. Owing, therefore, to the universal interest in pictures and the almost universal desire to produce them, the placing in the hands of the general public a means of making pictures with but little labor and requiring less knowledge has of necessity been followed by the production of millions of photographs. It is due to this fatal facility that photography as a picture‐making medium has fallen into disrepute in so many quarters; and because there are few people who are not familiar with scores of inferior photographs the popular verdict finds all photographers professionals or ʺfiends.ʺ

Nothing could be farther from the truth than this, and in the photographic world today there are recognized but three classes of photographers — the ignorant, the purely technical, and the artistic. To the pursuit, the first bring nothing but what is not desirable; the second, a purely technical education obtained after years of study; and the third bring the feeling and inspiration of the artist, to which is added afterward the purely technical knowledge. This class devote the best part of their lives to the work, and it is only after an intimate acquaintance with them and their productions that the casual observer comes to realize the fact that the ability to make a truly artistic photograph is not acquired offhand, but is the result of an artistic instinct coupled with years of labor. It will help to a better understanding of this point to quote the language of a great authority on pictorial photography, one to whom it owes more than to any other man, Dr. P. H. Emerson. In his work, ʺNaturalistic Photography,ʺ he says:

Photography has been called an irresponsive medium. This is much the same as calling it a mechanical process. A great paradox which has been combated is the assumption that because photography is not ‘hand‐work,ʹ as the public say—though we find there is very much ʹhand‐workʹ and head‐work in it—therefore it is not an art language. This is a fallacy born of thoughtlessness. The painter learns his technique in order to speak, and he considers painting a mental process. So with photography, speaking artistically of it, it is a very severe mental process, and taxes all the artistʹs energies even after he has mastered technique. The point is, what you have to say and how to say it. The originality of a work of art refers to the originality of the thing expressed and the way it is expressed, whether it be in poetry, photography, or painting. That one technique is more difficult than another to learn no one will deny; but the greatest thoughts have been expressed by means of the simplest technique, writing.

In the infancy of photography, as applied to the making of pictures, it was generally supposed that after the selection of the subjects, the posing, fighting, exposure, and development, every succeeding step was purely mechanical, requiring little or no thought. … Within the last few years, or since the more serious of the photographic workers began to realize the great possibilities of the medium in which they worked on the one hand, and its demands on the other, and brought to their labors a knowledge of art and its great principles, there has been a marked change in all this. Lens, camera, plate, developing‐baths, printing process, and the like are used by them simply as tools for the elaboration of their ideas, and not as tyrants to enslave and dwarf them, as had been the case.

The statement that the photographic apparatus, lens, camera, plate, etc., are pliant tools and not mechanical tyrants, will even today come as a shock to many who have tacitly accepted the popular verdict to the contrary. It must be admitted that this verdict was based upon a great mass of the evidence—mechanical professional work. This evidence, however, was not of the best kind to support such a verdict. It unquestionably established that nine‐tenths of the photographic work put before the public was purely mechanical; but to argue therefore that all photographic work must therefore be mechanical was to argue from the premise to an inconsequent conclusion, a fact that a brief examination of some of the photographic processes will demonstrate beyond contradiction. Consider, for example, the question of the development of a plate. The accepted idea is that it is simply immersed in a developing solution, allowed to develop to a certain point, and fixed: and that, beyond a care that it be not overdeveloped or fogged, nothing further is required. This, however, is far from the truth. … The turning out of prints likewise is a plastic and not a mechanical process. It is true that it can be made mechanical by the craftsman, just as the brush becomes a mechanical agent in the hands of the mere copyist who turns out hundreds of paint‐covered canvases without being entitled to be ranked as an artist; but in proper hands printmaking is essentially plastic in its nature. …

With the actual beauties of the original scene, and its tonal values ever before the mindʹs eye during the development, the print is so developed as to render all these as they impressed the maker of the print; and as no two people are ever impressed in quite the same way, no two interpretations will ever be alike. To this is due the fact that from their pictures it is as easy a matter to recognize the style of the leading workers in the photographic world as it is to recognize that of Rembrandt or Reynolds. In engraving, art stops when the engraver finishes his work, and from that time on the process becomes a mechanical one; and to change the results the plate must be altered. With the skilled photographer, on the contrary, a variety of interpretations may be given of a plate or negative without any alterations whatever in the negative, which may at any time be used for striking off a quantity of purely mechanical prints. …

With the appreciation of the plastic nature of the photographic processes came the improvement in the methods above described and the introduction of many others. With them the art‐movement, as such, took a more definite shape, and, though yet in its infancy, gives promise of a robust maturity. The men who were responsible for all this were masters and at the same time innovators, and while they realized that, like the painter and the engraver their art had its limitations, they also appreciated what up to their time was not generally supposed to be the fact, that the accessories necessary for the production of a photograph admitted of the giving expression to individual and original ideas in an original and distinct manner, and that photographs could be realistic and impressionistic just as their maker was moved by one or the other influence.

… And that the art‐loving public is rapidly coming to appreciate this is evidenced by the fact that there are many private art collections today that number among their pictures original photographs that have been purchased because of their real artistic merit. The significance of this will be the more marked when the prices paid for some of these pictures are considered, it being not an unusual thing to hear of a single photograph having been sold to some collector for upward of one hundred dollars. [Editorial note: $100 in 1899 would be about $4,000 in current purchasing power.] Of the permanent merit of these pictures posterity must be the judge, as is the case with every production in any branch of art designed to endure beyond the period of a generation.

The field open to pictorial photography is today practically unlimited. To the general public that acquires its knowledge of the scope and limitations of modern photography from professional show windows and photo‐supply cases, the statement that the photographer of today enters practically nearly every field that the painter treads, barring that of color, will come as something of a revelation. Yet such is the case: portrait work, genre‐studies, landscapes, and marine, these and a thousand other subjects occupy his attention. Every phase of light and atmosphere is studied from its artistic point of view, and as a result we have the beautiful night pictures, actually taken at the time depicted, storm scenes, approaching storms, marvelous sunset‐skies, all of which are already familiar to magazine readers. And it is not sufficient that these pictures be true in their rendering of tonal‐values of the place and hour they portray, but they must also be so as to the correctness of their composition. In order to produce them their maker must be quite as familiar with the laws of composition as is the landscape or portrait painter; a fact not generally understood. Metropolitan scenes, homely in themselves, have been presented in such a way as to impart to them a permanent value because of the poetic conception of the subject displayed in their rendering. In portraiture, retouching and the vulgar ʺshineʺ have been entirely done away with, and instead we have portraits that are strong with the characteristic traits of the sitter. In this department headrests, artificial backgrounds, carved chairs, and the like are now to be found only in the workshops of the inartistic craftsman, that class of so‐called portrait photographers whose sole claim to the artistic is the glaring sign hung without their shops bearing the legend, ʺArtistic Photographs Made Within.ʺ The attitude of the general public toward modern photography was never better illustrated than by the remark of an art student at a recent exhibition. The speaker had gone from ʺgum printʺ to ʺplatinum,ʺ and from landscape to genre‐study, with evident and ever‐increasing surprise; had noted that instead of being purely mechanical, the printing processes were distinctly individual, and that the negative never twice yielded the same sort of print; had seen how wonderfully true the tonal renderings, how strong the portraits, how free from the stiff, characterless countenance of the average professional work, and in a word how full of feeling and thought was every picture shown. Then came the words, ʺBut this is not photography!ʺ Was this true? No! For years the photographer has moved onward first by steps, and finally by strides and leaps, and, though the world knew but little of his work, advanced and improved till he has brought his art to its present state of perfection. This is the real photography, the photography of today; and that which the world is accustomed to regard as pictorial photography is not the real photography, but an ignorant imposition.

From a Letter to J. Dudley Johnston, April 1925:

I do not make ʺpictures,ʺ that is I never was a snap‐shotter in the sense I feel [Alvin Langdon] Coburn is. I have a vision of life and I try to find equivalents for it sometimes in the form of photographs. Itʹs because of the lack of inner vision amongst those who photograph that there are really but few true photographers. The spirit of my ʺearlyʺ work is the same spirit of my ʺlaterʺ work. Of course I have grown, have developed, ʺknowʺ much more, am more ʺconsciousʺ perhaps of what I am trying to do. So what I may have gained in form — in maturity — I may have lost in another direction. There is no such thing as progress or improvement in art. There is art or no art. There is nothing in between.