2 Essence and Peddlers

The remote Massachusetts hill town of Ashfield was not the most obvious base of operation for an essence-peddling business. The first road into the town was a woodland trail from Deerfield and the Connecticut River Valley. Weekly stage and post service from Northampton was not established until 1789, and there was no post office until 1814, when Levi Cook became postmaster and devoted a corner of his saddle shop to distributing the weekly mail. All of Ashfield celebrated in March 1824 when a daily mail stage from Greenfield to Albany, New York, began making early morning stops.[1] The stage started from Greenfield at three o’clock each morning and reached Ashfield via Conway between five and six. According to a resident who remembered the service, “It was a lively scene when in the early dawn, with the bugle blasts, the four horse coach rolled into the street from the east with its eight or ten passengers, pulled up at the hotel to change horses, while Esquire Cook hurried to change the mail; then on through Spruce Corner and Plainfield . . . to Bowker’s in Savoy, to Adams, and on to Albany, where they arrived the next morning at three.” The fare from Greenfield to Albany was three dollars.[2]

Peppermint oil had likely been carried through the Berkshires along what would become the mail route between Ashfield and Albany long before Samuel Ranney brought peppermint roots to Ashfield. Lanesboro distillers had grown, distilled, and sold peppermint oil and essence since 1800, and Pittsfield and Lenox entered the business in the 1820s.[3] But the unprecedented scale of peppermint growing in Ashfield and the lucrative peddler trade Henry Ranney helped develop brought Ashfield the lion’s share of the credit for propelling the peppermint oil industry through its first phase of development.

From the time that Samuel Ranney first planted peppermint roots in Ashfield, around 1812, the town’s peppermint oil business grew rapidly. Many histories of agriculture and of the “market transition” in the early republic focus on the subsistence-first nature of farming, especially in remote rural communities.[4] Historians observe that commodities such as wheat, barley, and apples had primary uses as food products. Surpluses might be fermented and distilled for storage, home use, or sale, but these uses were secondary. In contrast, peppermint was not a food and had limited value as a perishable fresh herb. The only reason to plant fields of peppermint was to distill it and sell the oil. All the primary accounts of distilling in Ashfield agree that although the town’s stills were occasionally used to produce other spirits, they were built to process peppermint and other essential oils. Counting Ashfield’s stills in the 1820s and early 1830s thus shows the rapid growth of the peppermint business and its abrupt change around 1835.

Ashfield’s tax records for 1826 show that Samuel Ranney’s property consisted of “2 Houses 2 Barns & Sheds, 35 acres improved Land, 56 D[itt]o unimproved, 1 still & still house.” Samuel built the sprawling house that still stands by the side of Route 116 in 1821. His brothers Jesse and George Jr. had similar improved acreages nearby and presumably distilled their peppermint using his still. Samuel’s cousin Roswell Ranney owned “2 Houses 2 Barns & Sheds, 1 still, still house & Cider Mill & other buildings, 1 sawmill, gristmill, 117 acres improved land, 100 D[itt]o unimproved.” Although a later arrival to Ashfield than his cousins, by the mid-1820s Roswell was already one of the town’s most prosperous farmers.[5]

Roswell, the son of George Ranney Sr.’s younger brother Thomas, had arrived in Ashfield in 1792 at the age of ten. He was an energetic young man and in 1821 was one of only ten farmers in the town who managed to harvest as much as fifty bushels of corn annually. In 1803, Roswell married Irinda Bement, a cousin of the local merchant Jasper Bement, who later mentored Henry Ranney in his mercantile business and entered the essence business. Roswell was active in local politics, leading town meetings and serving twice as militia captain and twice as representative to the legislature in Boston.[6]

In 1828, Ashfield’s tax assessors found even more stills. Roswell’s brother-in-law Samuel Bement owned a “Still & House.” Jasper Bement had built a still and a still house and had a half-interest in a cider mill. A few more cider mills appeared over the years, and since peppermint distilling is seasonal work, Ashfield’s stills were occasionally put to other uses in the off-season. But the fact that Ashfield never produced a surplus of grain supports the claim made in all the memoirs and histories that the main purpose of Ashfield’s stills was distilling peppermint and other essential oils.[7] By 1830, the number of peppermint distillers in Ashfield had increased dramatically. Tax assessors listed ten stills in operation. In addition to Samuel and Roswell Ranney and Jasper Bement, five other Ashfield farmers had built stills and still houses. Even the namesake nephew of River God Israel Williams operated two stills. Although local distillers did not know it at the time, the 1830 assessment marked the peak of peppermint oil production in Ashfield.

Itinerant sales or peddling is probably as old as civilization. The practice was well established in Europe in the Middle Ages and seems to have begun in the Americas as soon as Europeans settled here.[8] Peddlers sold a surprisingly wide variety of goods in early America, ranging from small, inexpensive items such as pins, ribbons, and buttons to tinware, clocks, pottery, chairs, and even washing machines. Low population density and underdeveloped transportation networks made peddling a relatively efficient way to bring manufactured goods to rural markets, and the presence of a salesman in a remote farmyard or kitchen was a strong influence on rural people to consume goods produced beyond the bounds of home production or even their local market. Some historians have suggested that peddlers helped create a culture of consumption in early America.[9]

Most histories of peddling focus on two well-documented groups of peddlers: the Yankee peddlers of Connecticut and the Jewish peddlers of the second half of the nineteenth century.[10] An important group of early American peddlers has been all but forgotten. Although essence peddlers were ubiquitous enough in the first half of the nineteenth century to become the subjects of songs, jokes, cartoons, and the source of a slang term for skunk, a contemporary search for the term “essence peddler” in historical writing returns only a 1949 article entitled “The Social Significance of the Language of the American Frontier.”[11] The fact that this article locates the origin of “essence peddler” on the American frontier in 1838, however, is telling. Young men from Ashfield were frequent enough visitors to remote frontier farmsteads that they were memorialized in language long after their disappearance from the American social scene.

Closer to home and to their own time, some nineteenth-century regional historians remembered the trunk- and basket-carrying foot peddlers of Ashfield in their histories of the region. An 1888 history of Ashfield remarked that it was “not far from truth to say that about the first and second generations in the present century of New England youths, when they attained to years approaching manhood, invariably supplied themselves with a pair of willow baskets or tin trunks, and with these well filled with oils, essences, pins, needles, thread, etc., suspended from their shoulders with a yoke, started out from the parental fireside to ‘see the world’ and prospect for a situation in life.” The local historian recalled that “many thousands of these young men, full of life and energy, and Yankee sagacity, thus equipped, perambulated New York and the western States” (original emphasis). Young men from Ashfield visited “all the newer sections of the West,” and many found themselves homes and careers in the territories they had explored as itinerant salesmen. Although a bit self-congratulatory, these accounts make the important point that Ashfield peddlers helped spread not only commerce into newly settled western regions but also some degree of the Yankee culture the historians regarded as “New England’s best genius, independence and love of justice and liberty.”[12]

Day: Order of the Grand Procession.”

A few historians have joined Ashfield’s locals in recognizing essence peddlers. Richardson Wright, an early historian of peddling, wrote that peddlers covered the entire settled area of the United States and “played an unforgettable role in the romance of our early widening frontiers.” Wright observed, “Even Horn’s Overland Guide to California—the Baedecker of the forty-niners—contains the advertisement of a Mr. Sypher in Fort Des Moines, who is willing to supply peddlers . . . at the lowest possible rates.” “The essence peddler,” continued Wright, “was quite a different sort” from the typical Yankee peddler. “Usually a free-lance, he managed to scrape together ten or twenty dollars [and] fill his tin trunk with peppermint, bergamot, and wintergreen extracts and bitters. In the backwoods these bitters were in great demand. They were mixed with the local brand of homemade liquor. . . . Other extracts were used as remedies and antidotes.” Undoubtedly the use of essences to flavor unpalatable local alcohol, in addition to the medical uses discussed earlier, would have substantially expanded the market for peppermint and other strongly flavored essences.[13] An indication that Wright may have been correct about the popularity of essences as flavorings for alcohol can be seen in an 1802 advertisement by a Philadelphia distillery: “The Large Rum Distillery in New Street, No. 13. Is now taking in Molasses, returnable in good flavored Rum. . . . Where also, may constantly be had on exchange or otherwise Anniseed, Cinnamon, Peppermint, Caraway . . . and other Cordials in usual request.”[14]

Some historians of the market transition have suggested that remote frontier settlements operated without commerce; a few have even claimed that settlers may have fled to the frontier to escape the “getting and spending” of eastern cities.[15] The story of peddling, in contrast, suggests that peddlers brought manufactured goods and market sensibilities to the remotest frontier outposts.[16] However much peddling may be implicated in the market transition, it is clear that peddlers helped people moving to the frontiers retain a connection with Atlantic commercial markets that had existed since Europeans began coming to the Americas. Peddling was a continuation of a type of commerce that had existed in Europe long before the colonial era. As American families moved westward, away from coastal cities, peddlers kept them connected with economies beyond their remote rural communities. Many historians have characterized rural people as producers of food and raw material for urban and export markets, suggesting that farmers in remote districts did not become consumers until merchants were able to ship urban goods to their stores via rivers, canals, or rail.[17] Yankee peddlers who visited farms and villages in remote areas of their own regions as well as on the frontier were of great cultural significance. They brought news, ideas, and an opportunity to be consumers as well as producers to people who might not otherwise have had these options.

In some cases, historical references to Ashfield’s essence peddlers have been mistaken for accounts of their Yankee confederates in Connecticut. A passage from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s diary that often finds its way into such comingled accounts actually mentions Ashfield by name. Hawthorne described a trip by coach from Worcester to Northampton in the mid-1830s. After riding outside for most of the day chatting with the driver, Hawthorne said the coach “took up an essence-vendor for a short distance. He was returning home, after having been out on a tour two or three weeks, and had nearly exhausted his stock. He was not exclusively an essence-pedlar, having a large tin box, which had been filled with dry goods, combs, jewelry, &c., now mostly sold out.” The essences, Hawthorne discovered, “are concocted at Ashfield, and the pedlars are sent about with vast quantities.”

Hawthorne wrote that the peddler was “good-natured and communicative, and spoke very frankly about his trade, which he seemed to like better than farming, though his experience of it [was] yet brief.” The young Ashfielder “spoke of the trials of temper to which pedlars are subjected, but said that it was necessary to be forbearing, because the same road must be traveled again and again. The pedlars find satisfaction for all contumelies in making good bargains out of their customers,” Hawthorne explained. The peddler was on a short circuit but was considering making a longer trip westward, “in which case he would send on quantities of his wares ahead to different stations.” Sending resupply shipments to stops along a larger route helped peddlers avoid carrying too much inventory. Hawthorne concluded that the “driver was an acquaintance of the pedlar, and so gave him his drive for nothing, though the pedlar pretended to wish to force some silver into his hand; and afterwards he got down to water the horses, while the driver was busy with other matters.”[18]

Hawthorne’s observations highlight important details of Ashfield peddlers’ work. Most were young men, and many peddled for just a short time to raise a stake and enter another venture. Most traveled on foot, carrying wicker baskets of essences and tin trunks of other goods, suspended by webbing and sometimes hung from a wooden yoke. Occasionally peddlers traveled in wagons, but this was much less prevalent with Ashfielders than with tinsmiths or the Connecticut vendors of bulky items like clocks. More often, a peddler traveling a lengthy route planned ahead and shipped resupplies to post offices along the route. Sometimes, when sales exceeded expectations, peddlers wrote to the Ashfield merchants who supplied them, to have additional stock forwarded to the next town on their way. These requests depended on the post, because the telegraph did not reach Ashfield until the 1890s.[19]

Hawthorne mentioned the “contumelies” experienced by peddlers. Anyone who has worked in sales can imagine the frustrations faced by door-to-door salesmen; but in many remote communities, peddlers were welcomed, or at least tolerated, because they carried needed products. Although peddlers like the young men of Ashfield became subjects of cartoons, jokes, and even popular songs, there was great demand for the products they carried.[20] And despite contemporary accounts like Thomas Hamilton’s 1833 “Men and Manners in America,” which claimed, “The whole race of Yankee peddlers in particular are proverbial for dishonesty,” the numbers of New Englanders making their fortunes as salesmen increased throughout the first half of the century. Hamilton complained, “They go forth annually in the thousands to lie, cog, cheat, swindle, in short, to get possession of their neighbor’s property in any manner it can be done with impunity. Their ingenuity in deception is confessedly very great.”[21] He was right, at least with respect to the peddlers’ numbers. In 1850 one account estimated there were 10,669 peddlers traveling America’s roads. A decade later, the number had grown to 16,595.[22]

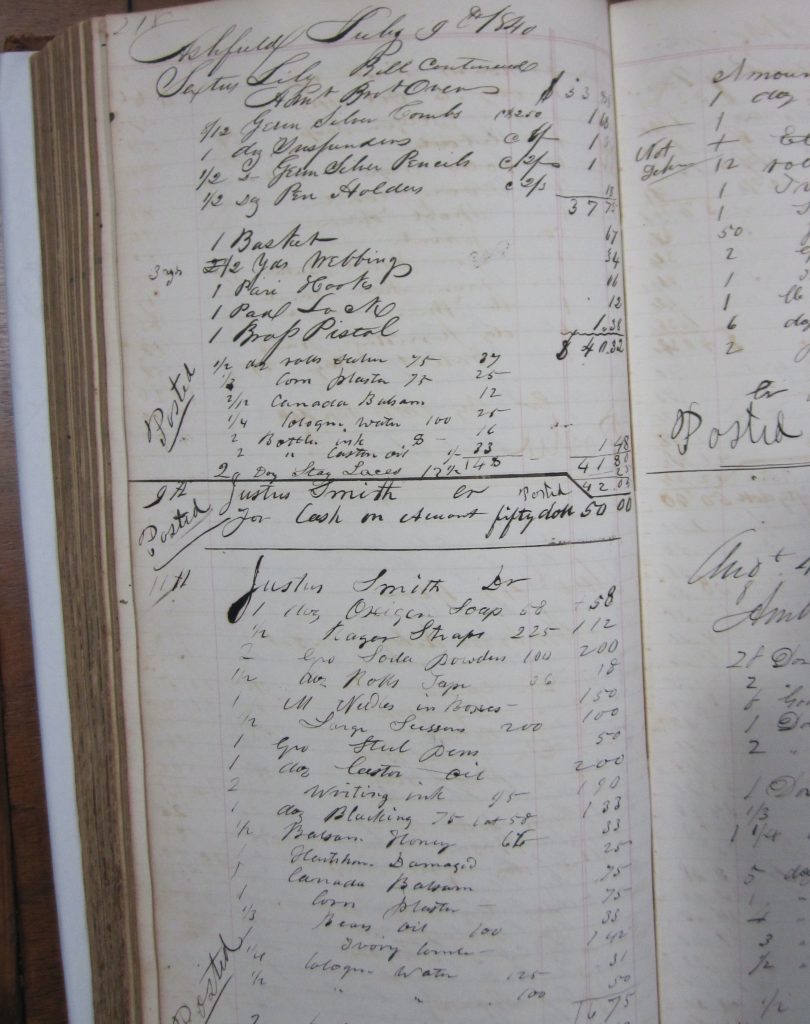

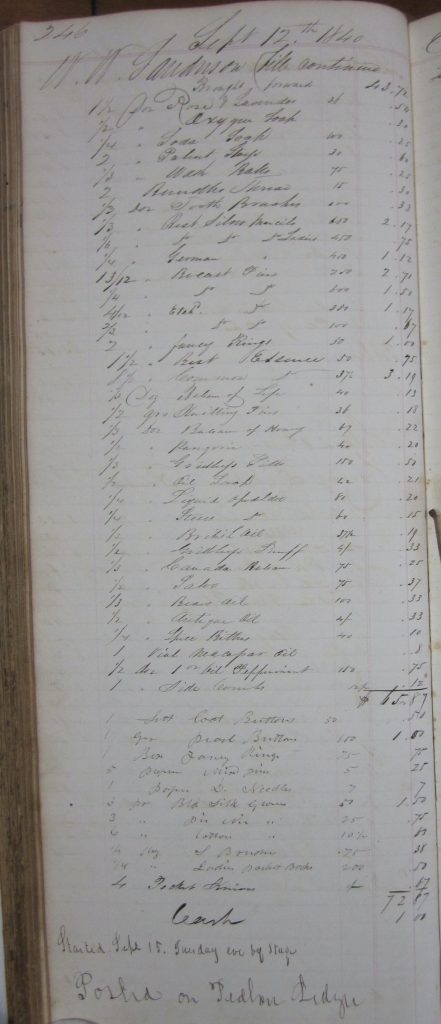

Although other itinerant salesmen offered lines of credit to their customers, and often priced products such as clocks and furniture to reflect carried interest and the risks and costs of collection, Ashfield peddlers did their business using cash.[23] They carried hard money, and as a result many traveled armed. In addition to essences, other wares, and the baskets and trunks used to carry them, Ashfield merchants like Jasper Bement and Henry Ranney occasionally sold pistols to the young men they sent out on the road. For example, when Ashfield essence peddler Sextus Lilly made his first peddling trip in July 1840, his bill in Bement’s ledger included ten dozen essences, a variety of patent medicines, thread, needles, ink, pencils, combs, a basket for carrying the essences (67 cents), three yards of webbing (34 cents), a lock (12 cents), and a brass pistol ($1.38).[24]

Most of the peddlers of Ashfield were supplied by Jasper Bement and Henry Ranney. Other families, like the Beldings, were very active in the production and sale of peppermint oil. But Jasper Bement, with his son Joseph and their longtime friend and partner Henry Ranney, were the focus of Ashfield’s peddler business. Jasper Bement, whose cousin Irinda had married Roswell Ranney in 1803, had been involved with peppermint since at least the 1820s. Bement was among the owners of a still and still house listed in the Ashfield tax records of the 1820s and early 1830s. He opened a general store in Ashfield in the 1830s and either originated or quickly took over the provisioning of peddlers with Yankee notions and essences. When the R. G. Dun Company’s local credit investigator reported on Bement in September 1841, he described the business as “General Store. Jewelry. Patent Med, Yankee notions, &c.” and rated Bement’s creditworthiness as “good.” Two years later, the reporter added: “Good, consid prop, mtgs [mortgages], money at interest &c. besides what he has in trade.”[25]

Henry Sears Ranney (1817–1899) was the third son of George Ranney Jr. and grandson of the elder George Ranney who had moved to Ashfield from Middletown in 1780. His uncle Samuel had introduced peppermint to Ashfield five years before Henry was born. When his father moved the family to Phelps, New York, in August 1833, sixteen-year-old Henry remained in Ashfield to pursue a career as a merchant. He clerked for Jasper Bement and lived in Bement’s household for a time, preparing himself for life as a merchant in Ashfield and briefly in Boston. In 1893, Henry remembered Bement as “a successful merchant; a public-spirited man of strong and sterling characteristics, the most pronounced and active abolitionist & free-soiler of this region.” Henry had received his start in business working as a clerk in the store Bement owned and “a member of his family for six years—during which time,” Henry observed, “I failed to receive from him a cross or impatient word.”[26] In addition to their business association, Bement and Henry were both committed to the cause of abolishing slavery in America.

The entire Ranney family objected the institution of chattel slavery, as demonstrated in letters between Henry Ranney and his brothers that Henry collected throughout the nineteenth century. Henry’s friends were also Free-Soilers, and many of those activists were peddlers. Although they helped rural people remain connected to the wider world through the products they carried and their interactions with customers, Yankee peddlers were not welcomed by everyone when they arrived in a new town. Local merchants often saw the itinerants as competitors, and as early as 1717 Connecticut peddlers (who, as mentioned, often traveled with wagonloads of big-ticket items) found themselves taxed twenty shillings for each hundred pounds of goods they carried into a particular town. By the middle of the eighteenth century, many states had enacted license fees for peddlers.[27] Historian Richardson Wright remarked, “We can trace the dislike of the town for the country through practically all phases of itinerant life.” Despite the fact that “had there been no peddlers there would have been no countryside distribution, and . . . manufacturing, even of the humblest household sort, could never have survived, the peddler’s foe was the established, settled, town merchant.”[28] But commercial rivalry was not the only reason peddlers were unwelcome. Another cause, especially in the South, was that many peddlers were quite political. Henry Ranney’s customer and good friend the Ashfield career peddler William Sanderson was an ardent abolitionist who mentioned “Liberty Party” and “Free-Soil” politics regularly in letters to Henry. Along with the essences and “Yankee notions” in his inventory, Sanderson regularly carried copies of Slavery As It Is, Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses, a 225-page jeremiad written by Theodore Dwight Weld for the Anti-Slavery Society in 1839.[29] Although Sanderson and peddlers like him probably found many appreciative customers for abolitionist tracts in the New England countryside, their frankly expressed politics also alienated many, especially in the South and the West. If profits were paramount, it would have been much more prudent for peddlers to leave their politics at home. Ashfield peddlers like Sanderson continued the town’s long-standing tradition of political engagement, once again blurring the boundaries between local and national activism.

William Sanderson was one of Ashfield’s busiest peddlers in the late 1830s. In a single season, Sanderson made twenty trips, buying supplies from Henry Ranney and Jasper Bement every two and a half weeks. Bement and Ranney often sent Sanderson resupply orders to points as far from Ashfield as Brattleboro, Vermont, and Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Sanderson’s average order size for a trip was about fifty dollars. Sanderson paid forty cents for a dozen vials of Bement’s premium peppermint essence, six cents for pencils, forty-five cents for razors, thirty-seven and a half cents for a gross of pearl buttons, and $1.88 for a box of a thousand needles. It’s not difficult to imagine Sanderson at least doubling his money on each trip.[30]

Bement and Ranney supplied more than 120 peddlers annually. About half of them traveled at least once a month during the peddling season. Unlike Connecticut peddlers of tinware and clocks, who usually worked for wages, most of Ashfield’s essence peddlers were self-employed. Bement’s account books include only a couple of entries out of hundreds where the merchant seems to have paid a peddler to make a trip, and those entries could be interpreted in other ways. Bement had business relationships with people in many of the towns his peddlers visited, and peddlers often carried letters, goods, and cash for Ashfield businessmen. Nearly all the transactions with peddlers recorded in Bement’s account books were inventories of goods, charged to the peddler. Bement outfitted most of his peddlers on credit, which is unsurprising, as most of the young peddlers came from local families that did regular business with Bement. All the records listed products charged at consistent wholesale prices, indicating that the peddler set the retail price of his wares and pocketed the profit.[31]

Like Ranney and Bement’s other peddlers, William Sanderson took a wide variety of items, but by volume and by weight his most significant cargoes were always vials of essences, mostly peppermint. Peddlers regularly left Ashfield with baskets containing from twenty to a hundred dozen glass vials of essences, the most popular being peppermint. Essence vials were bulky, heavy, and fragile. They must have been uncomfortable to carry, but they were the Ashfield peddler’s core product line. Bement didn’t have to pay the young men to distribute his products: their popularity with the peddlers’ customers and their profitability made essences the leading product of Ashfield’s salesmen.

After several years of peddling, William Sanderson gained enough experience and made enough money to start his own general store in the nearby town of Whately. Still interested in politics, Sanderson corresponded with his friend Henry Ranney regularly. In the summer of 1845, Sanderson wrote: “The wind blows softly by my cottage, the cats fight nights, Whigs twist and turn to get into office and prevent slavery. Democrats brow beat them for so doing, but I can sit and read my Heralds of Freedom and enjoy the same which is listened to with profound silence. Not an abolitionist in the center of this town but my dear wife.”[32] Two years later, Sanderson wrote again to congratulate Henry on his new baby daughter and then ranted for two additional pages about the slave power.[33] Sanderson’s interest in abolition was by no means an isolated instance of Ashfield peddlers meddling in national politics. Southerners were right to be suspicious of Yankee peddlers—at least those from Ashfield. Jasper Bement and Henry Ranney were both active free-soil abolitionists and in the early 1840s formed the nucleus of a “Liberty Party” in Ashfeld. In 1843, Jasper Bement campaigned for state representative as a Liberty candidate and lost, but a year later he won.[34]

Although they were interested in their businesses, Bement and Ranney were passionate about abolition. In August 1844, Jasper Bement wrote to Henry Ranney from Syracuse, New York, where Bement had stopped on his way to Detroit. Bement touched briefly on business and then offered detailed descriptions of several conversations he had enjoyed with “Liberty men,” and the reactions of strangers to whom he had offered abolitionist tracts at a political gathering. Bement said he was introduced to “Mr. Jackson the editor of the Democratic Freeman of Liberty paper. He began with 30 subscribers and has now got 700. We are gaining ground in this quarter if I can judge from what I see.”[35] A few days later, Bement wrote again: “The country seems all alive with Whig and Loco mass meetings. By inquiring I find a respectable number of Liberty men in almost every place.” Bement told Ranney a local Liberty man solicited him to give a lecture to a group of nearly two hundred people in Hannibal. In addition to the forty Liberty activists present, Bement said, “the Whigs present were rocked up. Asked questions and disputed. Some of our friends started for home in high spirits singing the Liberty Ball. Some of the Whigs were almost ready to vote for Liberty, but they think they must vote Clay in this time to keep Texas out.”[36] In spite of being rural businessmen from a remote community in the hills of western Massachusetts, Bement and Ranney shared a lifelong involvement in national politics. They both represented Ashfield in the legislature in Boston, and they maintained a far-flung commercial network, as we will shortly see.

Peddlers were an ideal means to reach a widely distributed, rural retail market. But there were also concentrated urban markets, and each city and large town had its physicians, apothecaries, and patent medicine manufacturers. In 1802, for example, the Philadelphia Directory listed “Calvin Flora, peppermint maker, St. Tammany.” In 1804, the directory included “Boyl Jonathan, peppermint maker near 27 Brewers alley.”[37] Nor, as previously mentioned, was the only use of peppermint medicinal. In a society that drank at least four times the per capita volume of alcohol as modern America, the market for flavored cordials was substantial.[38] New York City distiller Michael Miller announced to readers of the 1803 Daily Advertiser supplies “at his CORDIAL DISTILLERY, No. 11 Barley street, three doors eastward of Broad-way, Anniseed, Mint, and Pepper-mint cordials.”[39] And in 1804 the American Distiller included a section entitled “How to make peppermint essence.”[40]

By 1805, production of peppermint essence was widespread enough that glass manufacturers did not need to await orders from merchants like Bement. A broker named William Little, of 49 State Street, Boston, advertised a diverse variety of surplus products, including “Window Glass [many sizes], . . . 40 groce essence of peppermint Phials, an assortment of warranted Anchors.”[41] Perhaps Little’s supplier had produced a large volume of vials imprinted with “Essence of Peppermint” for a specific customer and was selling a surplus quantity. But the fact that the broker expected to find a buyer simply by offering the vials within a list of disparate products suggests a fairly wide market.

An 1808 advertisement in Utica’s Columbian Gazette announced, “Drugs and Medicine, at the Sign of the Good Samaritan. Solomon Wolcott, Has received an addition to his former stock. . . . 1000 Ess. Peppermint. . . . Instruments: Mortars, Scales and Shop Furniture . . . Peppermint Bottles, &c. &c.”[42] And in 1809, an ad in the New York Gazette and General Advertiser advised of “Opium, &c. . . . 10 lb. Oil Peppermint, for sale by John Wade, 181 Water-street.”[43] A four-ounce vial of peppermint essence contained less than an ounce of peppermint oil, so ten pounds was enough oil to make quite a bit of retail product.

Wholesalers cast a wide net. In April 1814, the Washingtonian in Windsor, Vermont, carried an advertisement for peppermint oil for sale in Boston. At the “Wholesale and Retail Chemical and Drug Warehouse, No. 1, Liberty Square—Boston. Paul Spear, Jr. Has for sale” a long list of bulk products, including “50 d[itt]o. [pounds] Oil of Peppermint.”[44] City merchants advertised for distant buyers and also for suppliers of peppermint oil. In 1818, wholesalers “J. & T. L. Clark & Son, at 85 Maiden-lane,” advertised a hundred pounds of peppermint oil in the New York Gazette and General Advertiser, and J. Bissell and Co. advertised in Pittsfield, “Will contract for 200 pounds of Oil Peppermint and 50 Oil Wintergreen, to be delivered the 1st October, and will pay cash on delivery.”[45]

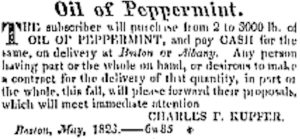

By the 1820s, when the peppermint oil business was reaching its maturity in Ashfield, the volume of oil that passed through the hands of urban wholesalers had also expanded rapidly. In May 1823, for example, Charles F. Kupfer, the superintendent of the Boston Glass Manufactory, ran an advertisement in the Pittsfield Sun. The Manufactory made essence vials like the ones used by Jasper Bement in Ashfield, but Kupfer was not above trying to fill the vials himself and take a bit of his clients’ profits. Kupfer announced in the Pittsfield Sun, whose readers included Hudson River and Erie Canal shippers, “The subscriber will purchase from 2 to 3000 lb. of OIL OF PEPPERMINT, and pay CASH for the same, on delivery at Boston or Albany. Any person having part or the whole on hand, or desirous to make a contract for the delivery of that quantity, in part or whole, this fall, will please forward their proposals, which will meet immediate attention.”[46]

Shipments of peppermint oil along the Erie Canal began in earnest, even before the canal was completed. Although construction continued to the west, the first 250 miles of canal between Brockport and the Hudson River opened in September 1823. This eastern section of the canal passed through Lyons, New York, which was directly north of the peppermint fields of Phelps, where many former Ashfielders had settled. In 1824, the Boston Commercial Gazette reran a notice from a newspaper in Geneva, New York, of a “New article of Domestic Manufacture”: “Last week was obtained from the Bank in this village, on a check, between two and three thousand dollars, being the proceeds of sales of Oil of Peppermint, manufactured in the town of Phelps, by F. Vandemark & Co. The past season, and sold to a person in Massachusetts.”[47] Frederick Vandermark was the brother-in-law of Archibald Burnett, the Ashfielder who first carried peppermint roots to western New York.

The success and prosperity of Ashfield’s peppermint growers did not go unnoticed. In 1825, Northampton’s Hampshire Gazette ran a feature story that was reprinted in newspapers all over the region, including the New Bedford Mercury and the Rhode Island American. The article described several hundred acres in Ashfield devoted to growing peppermint, with an average yield of between twenty-five and forty pounds of oil per acre. The article concluded, “The process of cultivation is said to be tedious and expensive, but we are inclined to think there are but few, if any crops raised in this part of the country that make greater returns for the money and labor expended on them.”[48]

In spite of expanding awareness of peppermint’s potential profitability and some large urban sales of wholesale peppermint oil, however, Ashfield continued to dominate the essential oil market through the 1820s. A letter about the products of Ashfield, written in 1824 and quoted in the History of the Town of Ashfield, “gives the value of peppermint oil made as over $40,000 yearly.” This is a significant sum: in comparison, the total value of the land and buildings in Ashfield in the town’s 1826 tax assessment was $9,812.38.[49] An 1833 report prepared by Andrew Jackson’s secretary of the treasury, Louis McLane, noted that Ashfield “has been somewhat celebrated for its manufacture of essences of various kinds, such as peppermint, hemlock, winter green, tansy, &c. It is estimated that 700 groce of essence, at $6 per groce, have been manufactured yearly, for several years past.” The report also declared that “the average amount of essential oils sold in New York, (exclusive of what has been used in the manufacture of essence in town) has been $3,000 worth, annually, for ten years past. It is considered fair business, when the oil will sell for $2 per pound; it is now worth $5 a pound.”[50]

The report listed $4,200 in essences plus another $3,000 in peppermint oil sold in New York City, for a total of $7,200. Since the reported New York wholesale receipts of $3,000 annually were an average over the previous ten years, when peppermint oil averaged two dollars per pound, the report implies that in addition to supplying essence peddlers, Ashfielders supplied the wholesale market with about fifteen hundred pounds of peppermint oil per year. Based on frequent newspaper notices of large transactions and the large quantities offered and solicited in advertisements, this may be a substantial underestimation.

The $4,200 listed for essence sales must also be considered a wholesale price, since it corresponds with prices charged by suppliers of peddlers like Jasper Bement. The reporter gave a price of six dollars per gross; Bement sold his peppermint essence to peddlers at forty cents per dozen. It is impossible to determine what the hundreds of peddlers taking essence into the countryside from Ashfield would have made on their sales. Some were probably better negotiators than others. But if the peddlers averaged forty cents per vial, their earnings would be consistent with the forty thousand dollars that Ashfield was reported to have made on oil annually in 1824. The wholesale prices reported by the Treasury Department are more relevant to comparisons with other industries, but since Ashfield’s economy relied much more heavily on retail peddler revenue than its neighbors, estimates of the income derived from peddling suggest the general prosperity of the town. It is also significant that, in keeping with Ashfield’s long-standing egalitarian ideals, the widespread prosperity of self-employed peddlers seems much more democratic than the concentrated wealth of other industries.

The other manufacturing activities Ashfield reported in the Treasury Department document were forging axes and hoes, worth $2,729; splitting four hundred thousand shingles, worth six hundred dollars; turning seven hundred thousand broom handles, worth $7,700; and making 3,300 pairs of boots and shoes, worth $4,950.[51] If peppermint oil had been an exclusively wholesale business, its significance to the town would have been merely equal to broom handles. The advantage Ashfield had over other regions involved in peppermint oil production was that the town’s economy was able to realize the retail value of the essences sold by peddlers who were overwhelmingly from Ashfield and nearby communities, while products like broom handles were simply sold in bulk at prices determined by a competitive wholesale market to “Hadley, Hatfield, and other towns on the Conn. River” that manufactured brooms. While some products such as shingles might have been produced by local free-lance workers, many were probably produced by wageworkers employed by sawmill owners. Rural communities were not immune to the shift from artisanal labor to wage labor; Ashfield was lucky to have had an economy built around a model of entrepreneurship that spread its rewards more widely and evenly.[52]

Ashfield’s $23,179 of wholesale manufacturing income in 1833 was similar to that of similar nearby towns. Conway reported manufactures worth $20,475, led by $13,600 in horn combs. New Salem manufactured ten thousand palm leaf hats, worth $27,500 when delivered to Boston and New York resellers, and had a leather and lumber business worth $9,550. The neighboring village of Buckland produced $9,750 in manufactures, including three hundred wooden clocks valued at $7.50 each. In the river valley were larger towns like Deerfield, which manufactured $58,600 in wholesale products, including 205,000 brooms and thirty thousand yards of wool satinet. But even when measured against these larger towns, Ashfield’s widely distributed retail income was substantial.

Another factor supporting claims of very high profits for Ashfield’s peppermint essence business is the extreme variability of peppermint oil prices. Demand for peppermint-based products was relatively constant and predictable, but supply varied widely from season to season. It was not uncommon for peppermint oil prices to double from one harvest to the next. In 1836, for example, a list of wholesale prices published in New York newspapers quoted “Oil of Peppermint” at $5.50 to $6.00. In comparison, imported opium was only $3.75 for Turkish and $3.95 for Egyptian.[53] In 1837, prices remained high. The Pittsfield Sun reported in December, in a notice reprinted as far away as Philadelphia: “Among the items received on the Hudson by the Erie Canal, we notice the singular one of 6,000 lbs. of oil of peppermint, valued at $30,000.”[54] When costs of a product’s key component, such as peppermint oil for peddlers’ essence vials, fluctuated widely, prices tended to be maintained at levels where retail sales could remain profitable even at the highest ingredient costs. This worst-case approach to pricing would lead to windfall profits for the peddlers, and especially for suppliers like Jasper Bement and Henry Ranney, when costs decreased.

In 1835, Ashfield’s tax assessors began recording the town’s assets in much greater detail. In addition to buildings and machines, financial assets and farm animals began to be counted and taxed. But for the first time the assessors of 1835 found no stills. George Ranney had moved to Phelps, New York, in 1833, and Roswell Ranney was making final preparations to follow him. Roswell’s taxable assets in Ashfield had dwindled by the summer of 1835 to a fractional interest in a sawmill worth a hundred dollars, a single horse and cow, and three thousand dollars “Money at interest.” One of the last members of the family to move to Phelps, Samuel Ranney had not yet begun selling off his assets. His 1835 assessment included houses and barns, acreage, and animals. But even Samuel no longer distilled peppermint oil in Ashfield.

The Ashfield merchant Jasper Bement, whose assets included a “Factory” and a “Shop” valued at seven hundred dollars, still bottled essences but no longer distilled peppermint oil. Bement’s other assets taxed in 1835 included four horses and a cow, “Stock in trade” worth $350, which probably consisted of the essences and wares he supplied to his peddlers, and two thousand dollars “Money at interest.” Bement’s relative by marriage Roswell Ranney seems to have been one of the early conduits of western New York peppermint oil to Ashfield. Jasper Bement’s account books show the shift in Roswell’s role, from local peppermint oil producer to broker of New York oil. In 1833 Bement’s account books had recorded handling fees Bement had charged Roswell to process oil, when Roswell had owned his own still. In 1836, after Roswell moved to Phelps, Bement’s accounts recorded transactions with Roswell involving bulk peppermint oil. And in 1838, after three years without a home of his own in Ashfield, Roswell Ranney was once again taxed for a small “House & Garden” in town, valued at a hundred dollars, as well as a cow and $3,020 “Money at interest.” Apparently, Roswell’s business connections with Ashfield remained substantial enough to justify a part-time residence on the town’s main street.[55]

As families like the Burnetts, the Ranneys, the Beldings, and the Bements left Ashfield and expanded peppermint growing and distilling into western New York (discussed in the next chapter), the town’s rocky, uneven fields were converted to pasture for the town’s growing herds of sheep. By 1835, when peppermint stills had disappeared from Ashfield, the town was home to 7,748 sheep valued at $1.25 each.[56] Even Roswell Ranney, who no longer lived in Ashfield full-time, invested in the new venture. In 1838, he was assessed for $2,652.50 of “money at interest” and for 150 sheep.[57]

In December 1833, the New England Farmer and Horticultural Journal and the Boston Courier reprinted an article from Greenfield’s Franklin Mercury that serves as a retrospective of the Ashfield peppermint venture. The article, entitled “Essence Peddling,” began: “There is not a town in the east, nor a prairie in the west of the United States, where the essences and the essence-peddlers of Yankee-land have not been seen and heard of: nor do we believe there is any business which has been so much celebrated and whose origin is yet so little known. It commenced about twenty years ago in Ashfield, in this county.” Although “a great many pretty properties were made there, while the place enjoyed a monopoly of the business[,] . . . [v]ast supplies are now derived by the Ashfield merchants from Phelps,” where many Ashfielders had recently moved. The article described peddlers who in “flocks of twenty or thirty have sometimes taken their departure from the place in a single day to the east, west, north and south, bearing ‘Goods from all nations lumbering at their back,’ making money and driving bargains with invincible perseverance under the very noses of the stationary traders.” The large number of full-time Ashfield peddlers, the article concluded, was increased by the “infinitely greater [number] of those who have made this business an apprenticeship to regular country trading, and an avenue to moderate wealth.”[58]

In addition to the ready availability of western New York peppermint oil that could be purchased from family and trusted friends, another factor that may have encouraged Ashfield merchants like Jasper Bement to give up distilling was a growing temperance movement in the town. As an Ashfield clergyman recalled in a memorial address reprinted in the town history, “The inhabitants of this town . . . have suffered much from the scourge of intemperance . . . many of the distilleries, first set up for the distillation of mint, by a little additional expense could be employed for a part of the year in distilling cider.” He described the movement he had led to discourage drinking, concluding that “although one or two distilleries, and a few retailing stores and some temperate drinkers stand in the way, yet the purifying process is in progress which will not stop until the whole town and region is reclaimed from the cruel grasp of this common enemy.”[59]

Although Ashfield’s “temperate drinkers” such as Bement and Henry Ranney seem to have thought the prohibition movement’s goals were themselves a bit intemperate, everyone admitted there was some truth to their claims. In May 1827, a group of Ashfield residents, including a deacon of the church, his sons, and several others, were washing sheep in the town pond. Under the influence, six men loaded two sheep into a large canoe and took it out on the pond. About ten yards from shore, the canoe sank. The deacon’s eighteen-year-old son, a twenty-eight-year old neighbor, and two brothers, aged fifteen and thirteen, went under and did not resurface. The deacon, who had been watching from shore, jumped into the water and also disappeared. All five drowned.[60]

While Ashfield’s famous essence business was not blamed for the 1827 tragedy, townsfolk regarded the stills with increasing suspicion. And many of the farmers who had done the difficult, time-consuming work of growing and distilling peppermint had moved to the area around Phelps in the early 1830s. Since the peppermint straw distilled into oil is bulky and perishable, distilling is always done as close to the fields as possible. When Ashfielders stopped growing their own peppermint, they no longer needed their stills. And the era of the Yankee essence peddlers persisted only as long as the single generation of merchants like Bement and Ranney who supplied them. Without peppermint and the widespread prosperity created by the peddler trade, Ashfield’s prominence faded. The 1910 History of Ashfield remarks, “It seems hardly credible that the cultivation of a single crop should have anything to do with the lessening of the population of Ashfield, but facts go to show that the rise and fall of the peppermint industry here affected the population seriously.”[61]

In the second half of the nineteenth century, many American farmers became enmeshed in commodity markets, sending their harvests and livestock to urban centers for processing into standardized food products. The details of this commercialization of agriculture vary from place to place and are key elements of the hotly debated market transition. Although the argument over the market transition often devolves into disagreements over the definitions of terms such as capitalism, the change in agency brought about by the rise of commodity agriculture and development of impersonal markets is a key to understanding the mentalities of rural people.[62] But too often historians have restricted their view to commodities such as wheat that were most suited to undifferentiated aggregation, shifting power from atomized producers to central processors.[63] In the most extreme examples of this reduction of agency, farmers lost their independence and became mere raw material suppliers for an industrialized food system.[64] But the well-documented history of this decline tends to obscure the fact that many early American farmers were innovators who worked hard to increase the diversity and value of the products they offered. As historian Martin Bruegel has observed, early American farmers “straddled two worlds that historians and ethnologists have often tended to construe as incompatible.”[65] When we fail to recognize that many rural people understood the complexity of the systems within which they operated, we deny the agency that seems very apparent in the actions and documents of the Ranneys and their associates.

Because most American farmers today grow monocultures of ever-decreasing diversity, it is easy to forget that since the beginning of the Columbian exchange, Euro-Americans and others have been importing new plants and animals and spreading them across the Americas.[66] Early American farmers were always on the lookout for new opportunities both to feed their families more efficiently and to produce novel products for local and distant markets. John Rolfe’s theft of high-quality tobacco from the Spanish Empire breathed new life into the Virginia colony at Jamestown. The reintroduction of potatoes, carried to Europe by the conquistadors after their discovery in the Andes, by Scots-Irish settlers in Maine created an industry that continues to this day. The American enthusiasm for chicken breeding that produced a “hen fever” in the early 1850s, the opening of Chinese ports after the Opium Wars, and the introduction of premium livestock breeds such as the Merino sheep that grazed on Ashfield’s pastures suggest a mental flexibility and interest in innovation that we do not currently associate with American farmers in particular and rural people in general.[67]

It should not be surprising that farmers like the Ranneys and their neighbors quickly took advantage of the opportunity to diversify and add value once Samuel Ranney had brought peppermint roots to Ashfield. It is worth restating, too, that the Ashfield farmers who grew and distilled peppermint between 1812 and 1835 produced a well-differentiated commercial product for a direct consumer market. Although most Ashfield farmers continued growing staples for their families and hay for their animals, there was no local-first, subsistence-to-surplus trajectory; peppermint was a commercial commodity from the outset. The peppermint oil industry challenges the paradigm that the undifferentiated nature of commercial agricultural products inevitably leads to the concentration of power in the hands of urban processors, and it suggests that the traditional agrarian history of independent yeomen gradually drawn into urban-dominated commercial markets that eliminated their agency is incomplete.

The Ranneys were central to the growth of the peppermint oil industry in western New York and Michigan, but they were not the first family to carry peppermint to western New York. Peppermint roots were introduced to Phelps by the Ranneys’ neighbor Archibald Burnett. It is fair to say, however, that the departure of most of the Ranneys from Ashfield caused the abrupt end of peppermint growing there.

The first Ranney family to sell off its stake in Ashfield and move to Phelps was that of George Jr., the youngest son of the senior George Ranney, who had first moved the family to Ashfield and was the inheritor of the original family farm. Youngest sons typically inherited in rural early America, because older sons usually had started their own families and farms long before their parents were prepared to retire. Youngest sons were still in the household when the parents became too old to work the farm, and they generally took over the work and cared for their parents in their declining years, in exchange for an inheritance.

George Ranney was well established in Ashfield when he decided to move. He had inherited the family farm in 1822, when his father George had died at the age of seventy-five. The younger George had married Achsah Sears in 1811, and they had eight sons and a daughter who lived to adulthood. In 1830, George’s property consisted of a house and barn, forty-six acres of improved farmland, and sixy-six acres of unimproved land. Although George’s property was valued at only about a third of his cousin Roswell’s, he was a substantial landowner running a successful farm in Ashfield.[68]

George sold out and in August 1833 moved his entire family to Phelps, except his third son, Henry, who remained in Ashfield, living in Jasper Bement’s household. Apparently pleased with the prospects of his new home, George encouraged his relatives to join him. In February 1835, Roswell’s son Horace Ranney bought a farm in Phelps, and in June 1837, Roswell made the first of several purchases in Phelps, buying a farm from peppermint farmer Frederick Vandermark. In February 1838, George bought a 105-acre farm on Flint Creek in Phelps, for five thousand dollars.[69] The substantial price Ranney paid shows that the region was already very well established by the time he arrived in western New York, and that the Ranneys were quite prosperous after their years in Ashfield.

Samuel Ranney’s move to Phelps in 1835 was certainly influenced by George, Horace, and Roswell’s success there. But Samuel’s decision to leave Ashfield seems also to have been precipitated by a new wave of social turmoil, revolving once again around Ashfield’s Congregational Church. In January 1834, Massachusetts finally disestablished the church, which had dominated the state since the days of the Puritans. Unlike New Hampshire to the north, which had separated church from state in 1790, and Connecticut to the south, which had banned government-supported religion in 1818, Massachusetts retained the Congregationalism of its colonial origins as the state’s official religion until 1833. Facing the sudden loss of its ability to forcibly tax the residents of Ashfield and compel their attendance, the church’s leaders looked for other ways to retain their authority.

The Ashfield church’s solution came in the form of an evangelist named Mason Grosvenor, who was called to Ashfield in his first ministerial assignment after graduating from Yale’s conservative divinity school. Grosvenor and the leaders of the Ashfield congregation immediately set to work combating what they characterized as extreme licentiousness in the town. Part of their program focused on prosecuting the town’s physician, Dr. Charles Knowlton, for publishing America’s first birth control manual. Another part involved admonishing residents whose attendance had lapsed and who had failed to pay their church tax. Grosvenor and the church leaders continued to use the word “tax” in spite of the fact they were no longer able to compel contributions with the force of law.[70]

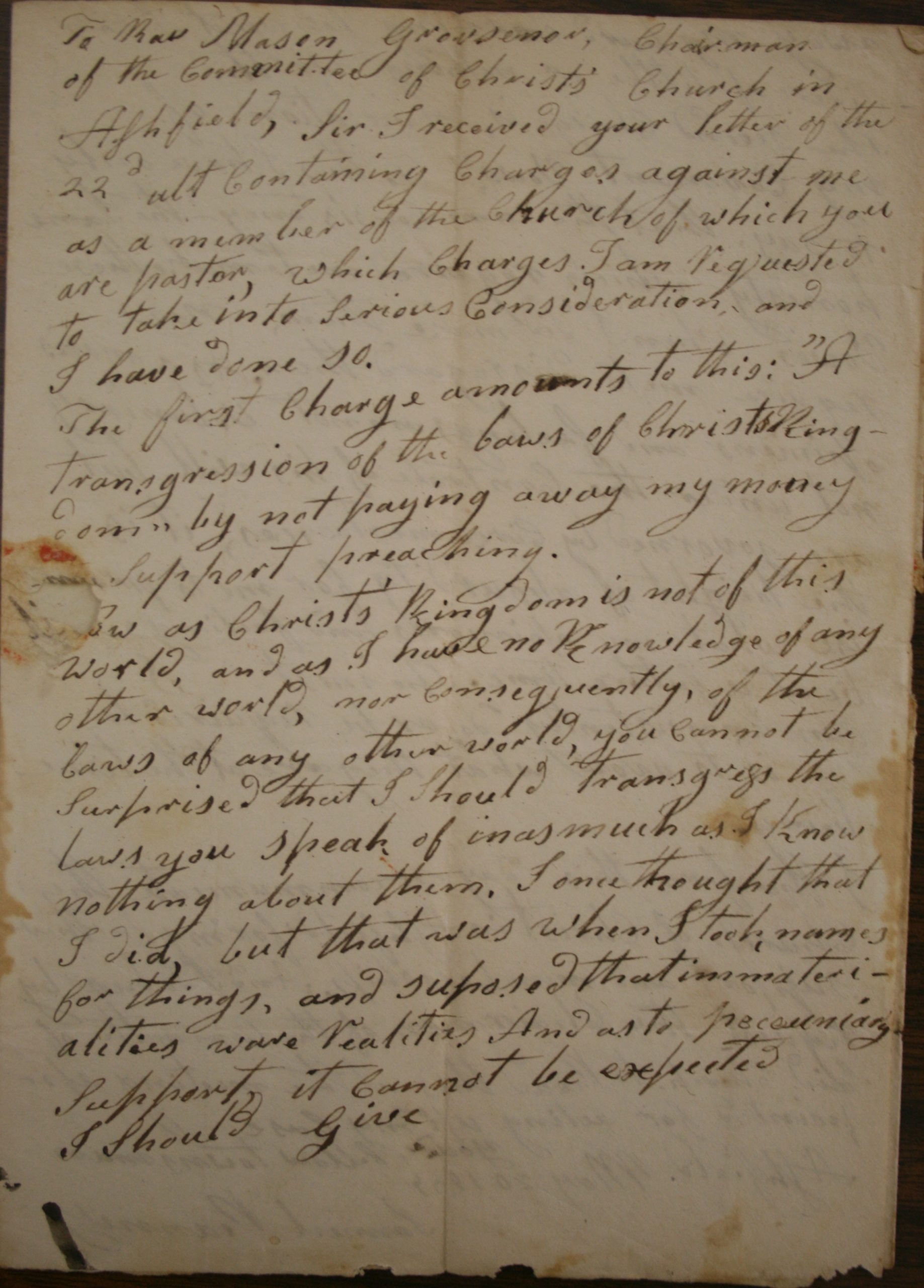

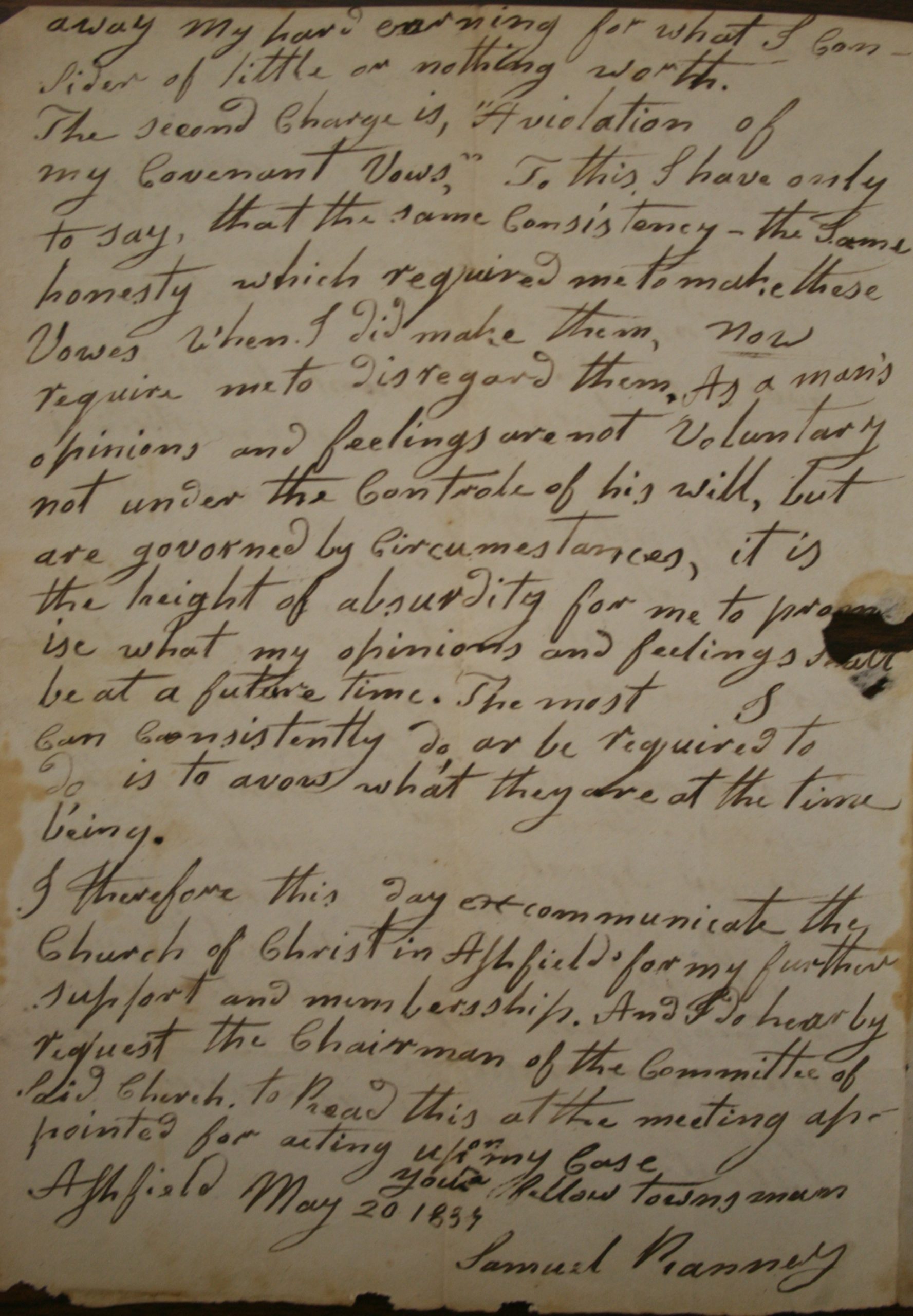

One of the church’s immediate targets was Samuel Ranney. The sixty-two-year-old farmer had neither attended services nor contributed to the congregation in years and may have seemed an easy target for a church leadership eager to set an example to intimidate the flock. Grosvenor drew up a list of charges against Ranney, accusing him of “a transgression of the laws of Christ’s kingdom by withholding his support both pecuniary and personal from the ministrations of the word to this church” and “a violation of his covenant vows, voluntarily solemnly and publicly made to this church and to god; consisting in almost entirely absenting himself for several years from the worship.”[71] In addition to failing to contribute and attend church services, Grosvenor wrote in his notes on the case, Samuel Ranney had “denied the existence reality of a future state, and declared himself not in the least responsible to the laws of Christ’s Kingdom,” which the minister declared “manifested contempt to this church, its laws its peace and its fellowship.”[72] The church wrote Ranney a letter of admonishment, insisting that he confess and repent his transgressions and immediately resume his attendance and financial support of the congregation. The alternative, church leaders warned, was excommunication.

Excommunication in a small, religious community such as Ashfield was not an idle threat. Like shunning in other traditional communities, excommunication split families and ruined lives. The church, under Grosvenor, had resorted to this punishment before, targeting another old Ashfield farmer, named Nathaniel Clark, who had been overheard in a tavern criticizing the congregation’s ongoing persecution of the town’s doctor, Knowlton. Clark had tried to protest the church’s actions to the Congregational hierarchy and had endured hearings and church tribunals before finally giving in and humbling himself before the congregation. Samuel Ranney was familiar with Clark’s case and did not take the threat lightly, but his reaction was not what the church expected. On May 20, at the conclusion of the four-week period the church had given him to consider its threat, Samuel Ranney delivered the following letter to Grosvenor:

To Rev Mason Grovsenor [sic], Chairman of the Committee of Christ’s Church in Ashfield,

Sir I received your letter of the 22d ult containing charges against me as a member of the church of which you are pastor, which charges I am requested to take into serious consideration, and I have done so.

The first charge amounts to this: “A transgression of the laws of Christ’s Kingdom” by not paying away my money to support preaching.

Now as Christ’s Kingdom is not of this world, and as I have no knowledge of any other world, nor consequently of the laws of any other world, you should not be surprised that I should transgress the laws you speak of inasmuch as I know nothing about them. I once thought that I did, but that was when I took names for things, and supposed that immaterialities were realities. And as to pecuniary support, it cannot be expected I should give away my hard earning for what I consider of little or nothing worth.

The second charge is, “A violation of my Covenant Vows.” To this I have only to say, that the same consistency—the same honesty which required me to make these vowes when I did make them, now require me to disregard them. As a man’s opinions and feelings are not voluntary nor under the control of his will, but are governed by circumstances, it is the height of absurdity for me to promise what my opinions and feelings shall be at a future time. The most I can consistently do or be required to do is avow what they are at the time being.

I therefore this day excommunicate the Church of Christ in Ashfield for my further support and membership. And I do hearby request the chairman of the committee of said church to read this at the meeting appointed for acting upon my case.

Your fellow townsman,

Ashfield, May 20 1834 Samuel Ranney[73]

Samuel Ranney’s letter is remarkable in several ways. First, of course, for Ranney’s dramatic, preemptive excommunication of the church. But also for Ranney’s discussion of names and things, immaterialities and realities. The language suggests Ranney was not a simple old farmer who had lost interest in supporting the church but rather was someone who entertained radical opinions about the role of religion in his life and in Ashfield society. The specific terminology he used also suggests familiarity with the ideas of the local freethinker, Dr. Charles Knowlton, who had published a book on the subject a few years earlier, entitled Elements of Modern Materialism.[74] The fact that Knowlton was a country doctor living in Ashfield and that Ranney was familiar with the argument of a 456-page atheist tome Knowlton had self-published suggests that in spite of its remote, rural setting Ashfield was the scene of one of America’s earliest philosophical challenges to organized religion. Knowlton had been prosecuted for offering copies of Elements of Modern Materialism to students at Amherst College, and he had lectured to freethinking audiences in Boston and New York City. Once again, rural Ashfielders were at the forefront of an intellectual and cultural movement traditionally believed the exclusive interest of urban intellectuals.

The apparently deliberate misspelling by Ranney of the pastor’s name and his decision to sign his letter to the church “Your fellow townsman” when the expected, customary closing would have been “Your brother in Christ” also seems to stand as an accusation against people Ranney believed had wrongly put religious orthodoxy before social solidarity and as an expression of his wider, more cosmopolitan concept of citizenship. Ironically but unsurprisingly, the words “Your fellow townsman” were true for only a few more months. Samuel sold his farm and followed his brother and cousins to Phelps in 1835.

At the same time the Ranneys were settling into Phelps, they were simultaneously setting the stage for the next phase of the family’s expansion across America by purchasing land in Michigan. In spite of President Andrew Jackson’s 1836 Specie Circular, which had declared that western lands had to be paid for at the Land Office with hard money rather than paper notes, in 1837 Samuel Ranney, his son William, and many of their Phelps neighbors traveled to the Detroit Land Office and bought land on the frontier. Perhaps the elimination of speculation based on credit in the form of paper banknotes had convinced the Ranneys and other New Yorkers that the opportunity presented by western land was legitimate. In any case, on March 13, 1837, Samuel bought a farm in Phelps, and on April 15, he and his son William purchased a 160-acre and a forty-acre parcel.[75]

Samuel’s health deteriorated rapidly, perhaps exacerbated by the controversy in Ashfield, the move to Phelps, and the trip to Michigan. Years later, Henry Ranney described his uncle as “enterprising and successful, but . . . overtaken by some misfortunes as age drew on. . . . [H]e made his abode in Phelps, but was broken in health, and died the following year.”[76] Samuel wrote his will in April 1837, naming his wife, Polly, and friend Russell Bement as his executors. He died on June 28, 1837, leaving his recently purchased Michigan land to his minor son Frederick. His estate inventory included notes for debts owed him by Russell Bement, by Samuel’s son-in-law, the Michigan merchant Nehemiah Hathaway, and by the local peppermint oil producers Vandermark and Company.[77] Samuel’s wife, Polly, and their four children all ultimately moved to Michigan, where at least one son, Frederick, remained active in the peppermint oil business. In 1847, Henry Ranney received a letter in Ashfield from his cousin Frederick, then living in Centerville, Michigan. Frederick wrote, “Dear Sir, I am obliged to call on you for the money on that peppermint oil that was sent last fall. I have some money to make out in a few days or sell property at a low price. Lucius nor Lewis [Henry’s brothers living near Frederick in Michigan] cannot help me to money this fall therefore I shall expect it in a return letter. You must write on the receipt of this for time is short with me. Let me know what you can do.”[78]

Although the first peppermint king had passed, the Ranneys remained active in the peppermint oil business. Roswell Ranney continued to prosper in New York, where he built a large house, a barn, and outbuildings, all of fieldstone. Roswell “dealt largely in peppermint and other essential oils,” acting as a conduit for New York peppermint oil into Ashfield and other eastern markets.79 Roswell kept between three and four thousand dollars “at interest” in Ashfield for years after he moved to Phelps and, as mentioned earlier, bought a small house on Ashfield’s main street in 1838. In 1845, one of New York’s new peppermint merchants, Leman Hotchkiss, wrote to his brother Hiram to tell him about peppermint oil “which old Ranney took to [the New York City broker] David Dows and requested him to ascertain the most he could obtain for it.”[79] Roswell remained active in the peppermint oil business well into the 1840s, when the Hotchkiss brothers are typically believed to have controlled the market. Apparently Roswell was acquainted with the same people in New York City, and his opinion was worth something even to his rivals, the Hotchkisses. A few days later, Leman wrote Hiram again to say “Old Ranney” had returned from his trip to New York and Boston and Leman had met with him. “He told me that if he had an offer for 10 Thousand pounds of oil for 10/ he would not take it. At the same time he said he had contracted 200# with one of his old customers in Boston & he no doubt should be obliged to pay 12/ to fill his contract.”[80] The “old customer” in Boston could well have been Roswell’s nephew Henry, who had a business in the city in 1845 and 1846.

Roswell died in September 1848 at the age of sixty-six—apparently unexpectedly, because he had not prepared a will. He left a substantial estate of $44,215.43, consisting of real estate, bonds, mortgages, and notes, which was distributed equally among seven beneficiaries.[81] With Roswell’s death, Henry Ranney in Ashfield became the principal member of the family involved in the peppermint oil business. But the business had expanded, and other families had taken the center stage. Our focus is on on Phelps and its peppermint kings in the next chapter, and then we revisit the Ranneys as they carry the first peppermint roots to Michigan, establishing a peppermint oil business that straddled the country from Boston and New York to the pioneer farms of the Yankee West.

- Everts and Co., 740. ↵

- Howes, 115–16. ↵

- David D. Field and Chester Dewey, A History of the County of Berkshire, Massachusetts, in Two Parts. The First Being a General View of the County; the Second, an Account of the Several Towns (Pittsfield: S. W. Bush, 1829). 86–87, 92, 177. ↵

- Clark, The Roots of Rural Capitalism. ↵

- 1826 Town Valuation of Ashfield; 1826 Town Tax Documents. ↵

- Williams, 70; Ashfield and New England Historic Genealogical Society, Vital Records of Ashfield, Massachusetts to the Year 1850 (Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1942), 249. ↵

- Town Valuation for 1830, 6/12/1830; 1830 Tax Records; Howes. ↵

- J. R. Dolan, The Yankee Peddlers of Early America (New York: C. N. Potter, 1964). ↵

- Wright. Paul J. Uselding, “Peddling in the Antebellum Economy: Precursor of Mass-Marketing or a Start in Life?” American Journal of Economics and Sociology 34, no. 1 (1975); David Jaffee, “Peddlers of Progress and the Transformation of the Rural North, 1760–1860,” Journal of American History 78, no. 2 (1991). ↵

- David Jaffee, A New Nation of Goods: The Material Culture of Early America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010); Hasia R. Diner, Roads Taken: The Great Jewish Migrations to the New World and the Peddlers Who Forged the Way (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015). ↵

- Merton Babcock, “The Social Significance of the Language of the American Frontier,” American Speech 24, no. 4 (1949). ↵

- E. R. Ellis, Biographical Sketches of Richard Ellis, the First Settler of Ashfield, Mass., and His Descendants (Detroit: W. Graham, 1888). ↵

- Wright, 25, 26, 56–57. ↵

- Gazette of the United States, 6/12/1802. ↵

- It should be noted that even Allan Kulikoff, one of the most vocal proponents of the “escape” thesis, acknowledged: “The rural economy of early America was clearly commercial.” Kulikoff, The Agrarian Origins of American Capitalism, 17. ↵

- Jaffee, “Peddlers of Progress.” ↵

- Walsh, The Rise of the Midwestern Meat Packing Industry; Martin Bruegel, Farm, Shop, Landing: The Rise of a Market Society in the Hudson Valley, 1780-1860 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002). ↵

- Nathaniel Hawthorne, The American Notebooks by Nathaniel Hawthorne (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1838), 60. ↵

- Michele P. Barker, Peddlers in New England, 1790–1860 (Sturbridge, Mass.: Old Sturbridge Village, 1992); Henry S. Ranney, "Peppermint in Phelps," Phelps Citizen, 1893. ↵

- For example, “Why is the dust in such a rage? / It is he yearly caravan / Of peddlers, on their pilgrimage / To southern marts; full of japan, / And tin, and wooden furniture, / That try to charm the passing eye; / And spices which, I’m very sure, / Ne’er saw the shores of Araby.” Connecticut poet Joseph H. Nichols, quoted in Wright, 29. ↵

- Ibid., 28. ↵

- Dolan, 231. ↵

- Priscilla Carrington Kline, “New Light on the Yankee Peddler,” New England Quarterly 12, no. 1 (1939), 85ff. ↵

- Jasper Bement Account Books, 1832–40. ↵

- Harvard: R. G. Dun reports, 1831. ↵

- Ashfield: H. S. Ranney to Phelps Citizen, “Peppermint in Phelps,” 1893. ↵

- Kline, 92–93. ↵

- Wright, 89. ↵

- Kline, 93; Barker. ↵

- Barker; Ashfield: Jasper Bement Account Books. ↵

- Ashfield: Jasper Bement Account Books. ↵

- Ashfield: Letter from William Sanderson to H. S. Ranney, 1845. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Howes, 217. ↵

- Ashfield: Letter from Jasper Bement to H. S. Ranney, August 23, 1844. ↵

- Letter from Jasper Bement to H. S. Ranney, August 26, 1844. ↵

- James Robinson and Abraham Shoemaker, The Philadelphia Directory, City and County Register, for 1802 Containing, the Names, Trades, and Residence of the Inhabitants of the City, Southwark, Northern Liberties, and Kensington: With Other Useful Tables and Lists (Philadelphia: William W. Woodward, 1802). James Robinson, The Philadelphia Directory for 1804 Containing the Names, Trades, and Residence of the Inhabitants of the City, Southwark, Northern Liberties, and Kensington: To Which Is Prefixed, a Brief Sketch of the Origin and Present State of the City of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: John H. Oswald, 1804). ↵

- Rorabaugh. ↵

- Daily Advertiser, 11/4/1803. ↵

- Michael Krafft, The American Distiller, or, the Theory and Practice of Distilling, According to the Latest Discoveries and Improvements, Including the Most Improved Methods of Constructing Stills, and of Rectification (Philadelphia: Thomas Dobson, 1804). ↵

- Boston Gazette, 11/18/1805. ↵

- “Drugs and Medicine,” Columbian Gazette, 2/9/1808. ↵

- “Opium, &c.,” New York Gazette and General Advertiser, 2/17/1809. ↵

- Paul Spear, Washingtonian, 4/25/1814. ↵

- “Drugs and Chemicals,” New York Gazette and General Advertiser, 10/9/1818; Phinehas Allen, The Pittsfield Sun, 1818. ↵

- Pittsfield Sun, 7/10/1823; Joan E. Kaiser, The Glass Industry in South Boston (Lebanon, N.H.: University Press of New England, 2009), 20, 58. ↵

- “New Article of Domestic Manufacture,” Boston Commercial Gazette, 1824. ↵

- Peppermint,” Rhode-Island American, 1825. ↵

- I have not been able to locate the source document for this quote, and it has occurred to me that the number might be exaggerated or the result of a transcription error. But the other statistics and values cited in the discussion surrounding this quote are all very accurate, which lends credibility to the data. Howes, 126. ↵

- Louis McLane, Documents Relative to the Manufactures in the United States Collected and Transmitted to the House of Representatives, in Compliance with a Resolution of Jan. 19, 1832, 22d Cong., 1st Sess. House. Doc; 308 (Washington, D.C.: D. Green, 1833). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Although he focused primarily on urban, immigrant labor, Bruce Laurie noted: “As late as 1860, more wage earners worked in farmhouses and in small workshops than in factories, and most used hand tools, not power-driven equipment.” Laurie, 16. ↵

- “Wholesale Prices,” 1836. ↵

- “Summary,” Pittsfield Sun, 12/21/1837. ↵

- Town Valuation for 1838, 1838 Ashfield Tax Records. Jasper Bement Account Books. Town Valuation for 1838. ↵

- Chester Sanderson, Town Valuation for 1835, 7/15/1835, 1835 Ashfield Tax Records. ↵

- Ashfield Town Valuation for 1838. ↵

- “Essence Peddling,” Boston Courier, 12/10/1833. ↵

- Howes, 41–42. ↵

- Ibid., 45. ↵

- Ibid. 103–4. ↵

- Clark, Social Change in America; Appleby, “The Vexed Story of Capitalism Told by American Historians.” ↵

- Parkerson. ↵

- Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis. ↵

- Bruegel, 42. ↵

- In addition to Euro-Americans, there were Africans, Asians, and South Americans who were instrumental in importing crops such as rice and alfalfa to North America. Edward D. Melillo, Strangers on Familiar Soil: Rediscovering the Chile-California Connection (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015); Judith Ann Carney, Black Rice: The African Origins of Rice Cultivation in the Americas (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2002); Sucheng Chan, This Bittersweet Soil: The Chinese in California Agriculture, 1860–1910 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986). ↵

- Geo P. Burnham, The History of the Hen Fever: A Humorous Record (Philadelphia: James French, 1855); Virginia DeJohn Anderson, Creatures of Empire:How Domestic Animals Transformed Early America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004). ↵

- Town Valuation for 1830; Ashfield Vital Records, 258. ↵

- Ontario County indentures (land sales), 1838. ↵

- These events are described in great detail in my biography of Knowlton. Allosso. ↵

- Ashfield: Mason Grosvenor, Congregational Church Records, 1834. ↵

- Strike-through in the original. Ibid. ↵

- Spelling errors—including the possibly deliberate misspelling of the pastors name—are original. Ashfield: Samuel Ranney Letter, 5/20/1834. ↵

- Charles Knowlton, Elements of Modern Materialism Inculcating the Idea of a Future State, in Which All Will Be More Happy, under Whatever Circumstances They May Be Placed Than If They Experienced No Misery in This Life (Adams, Mass.: A. Oakey, 1829). ↵

- U.S. Land Office records, April 15, 1837. ↵

- Ashfield: H. S. Ranney to Phelps Citizen, “Peppermint in Phelps,” 1893 ↵

- Samuel Ranney, Last Will and Testament, 1837. ↵

- Ashfield: Letter from L. G. Ranney to H. S. Ranney, 5/19/1839 ↵

- Cornell: Letter from L. B. Hotchkiss to H. G. Hotchkiss, 9/15/1845 ↵

- Cornell: Letter from L. B. Hotchkiss to H. G. Hotchkiss, 9/17/1845 ↵

- Roswell Ranney Estate Inventory, 1848. ↵