1 Peppermint in America

Peppermint probably arrived in Connecticut when Samuel Ranney, the first peppermint king, was growing up in Middletown. Samuel was born in 1772, while commerce in peppermint makes its first appearance in colonial America in the early 1760s with advertisements for peppermint essence in the New York Mercury and the New York Gazette in 1763 and 1764.[1] By 1770, advertisements for “Essence of Peppermint . . . an highly useful family medicine” were appearing in other New York newspapers, three Boston papers, and as far away as Pennsylvania and Georgia.[2]

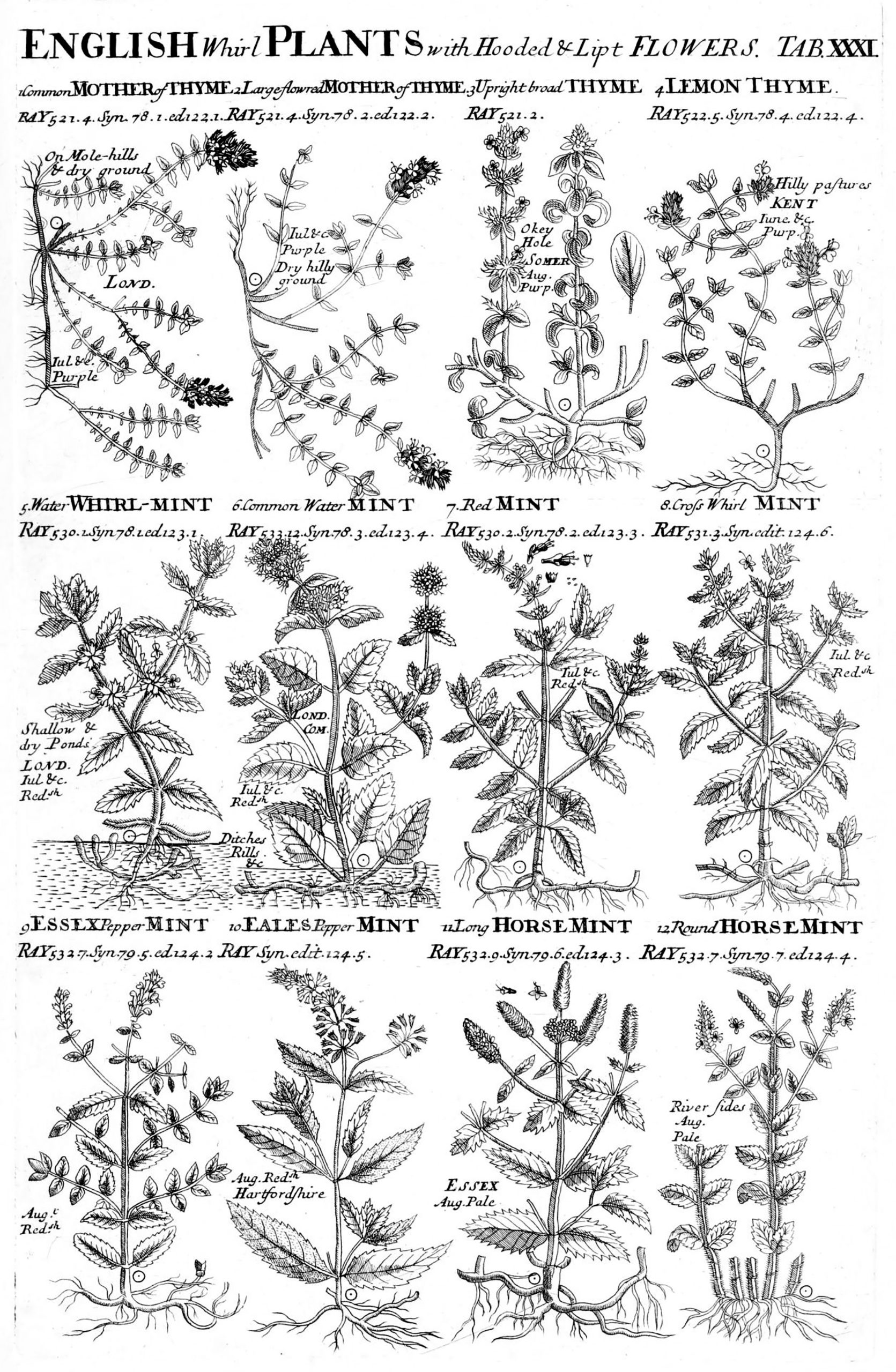

Peppermint essence, made by mixing peppermint oil with alcohol, was first manufactured in the London suburb of Mitcham, where hybrid peppermint plants were first commercially cultivated around 1750. Mentha piperita, a hybrid of spearmint and watermint, is a sterile hybrid that can only be propagated via root cuttings called stolons. Peppermint had been discovered growing by the side of streams and millponds in rural Essex in England around 1690.[3] Physicians and apothecaries had quickly recognized peppermint’s superior effectiveness in treating all the ailments for which more common mint varieties had been prescribed, and for a while they had attempted to keep peppermint secret to create a monopoly. Finally, “a tiny crumb” was smuggled by a rival apothecary and sprouted.[4] By the end of the eighteenth century about a hundred acres of peppermint was grown in Mitcham and three thousand pounds of essential oil distilled annually.[5]

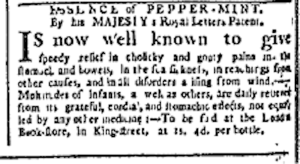

The first advertisement for imported peppermint essence in 1763 described its “very great . . . cordial and stomachick effects,” claiming peppermint essence “speedily relieves cholick, and gouty pains in the stomach and bowels, and all disorders arising from wind.” Most early advertisements specifically offered imported peppermint essence, sometimes “by His Majesty’s Royal Letters Patent.” Although it is unclear exactly when enterprising merchants first imported British peppermint roots to the colonies for cultivation there, Americans were growing and distilling their own peppermint well before the Revolution. In May 1768, a druggist named Robert Harris placed a notice in the Pennsylvania Chronicle and Universal Advertiser, looking to buy “Mint and Peppermint, fresh and in their season—of which any quantity will be purchased.”[6]

With the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, distinguishing between British and American peppermint products gained a new urgency for advertisers eager to capitalize on either the newfound patriotism of the rebellious colonists or the loyalty of royalists. Although London peppermint was still considered superior, only royalists carried British products. New York City, occupied by British forces until 1783, was a battlefield for imported and domestic peppermint products. In September 1778, New York’s Royal American Gazette carried an advertisement for, “By the KING’s PATENT. The Genuine Essence of PEPPER-MINT, SOLD WHOLESALE and RETAIL, BY RICHARD SPEAIGHT, Chymist.”[7] A few months later, Atwood’s Medicinal Store on Water Street offered readers of the New York Gazette and Weekly Mercury “some of the most approved Patent Medicines, such as . . . Essence of Peppermint.” The domestic nature of Atwood’s peppermint essence is confirmed by its offer in the same advertisement of “two commodius, elegant, and compleat chests adapted, with braces, for a Regimental Surgeon to be sold cheap.”[8]

The American Revolution was a repudiation of British rule, but not of commerce with Britain. London peppermint was still in demand in America. In the summer of 1784, Boston’s Independent Chronicle and Universal Advertiser announced, “Just imported, in the Ship UNITED STATES, A large Assortment of Drugs and Medicines, Which will be sold on the lowest terms for Cash or Credit . . . Essence of Peppermint.”[9] Although imported on a ship whose name celebrated the new nation, the cargo of London peppermint essence and other drugs shows there was still a ready market for British medicines in the newly united states. Nor was the perception that premium quality London peppermint commanded higher prices restricted to East Coast cities. In 1784, a western Massachusetts druggist advertised “Essence of Peppermint. . . . Just imported from London, And to be sold by Ebenezer Hunt jun. At his Apothecary Store, opposite the Meeting-House, in Northampton.”[10] Hunt’s advertisements appeared regularly in the Hampshire Gazette into the early 1800s.

By the last decade of the eighteenth century, markets for both English and American peppermint-based medicines were well established and growing quickly. In Salem, Massachusetts, the apothecary Jonathon Waldo sold vials of English essence of peppermint for eighteen shillings and his own domestic essence of peppermint for ten shillings sixpence a dozen. In 1799, Beverly druggist Robert Rantoul placed an order in London for a variety of English patent medicines and also for “empty vials in which to put British Oil and Essence of Peppermint.” Whether Rantoul actually intended to fill the vials with English peppermint is unknown, but according to historians of patent medicines, “for decades thereafter the catalogs of wholesale drug firms continued to specify two grades of various patent medicines for sale, termed ‘English’ and ‘American,’ ‘true’ and ‘common,’ or ‘genuine’ and ‘imitation.’”[11] A druggist’s 1797 advertisement in the Providence United States Chronicle, for example, announced “MEDICINES, genuine and fresh from EUROPE, which he will sell wholesale and retail, on as liberal Terms as may be had in New-England. . . . True Essence of Peppermint.”[12]

As time passed, domestic peppermint-based medicines gained ground. In the first decade of the 1800s, growing tensions between the new republic and Britain led to an American boycott of British products formalized in the Embargo Act of 1807. American leaders preached self-sufficiency and domestic manufacture, which gave local peppermint producers a valuable opportunity to expand their markets. In 1806, for example, the Eastern Argus of Portland, Maine, carried a notice for “NEWTON’S HIGHLY APPROVED ESSENCE OF PEPPERMINT, Having four times the strength of the Essence which is in common use, and is eight times as strong as some which is sold for good Essence, and will be always of equal strength. Prices 2/, 3/6 & 6/6.”[13] The advertisement made a claim about quality that was no longer tied to the origin of the product, implying that users should be able to distinguish quality peppermint essence without resorting to a simple distinction based on the source nation. In 1811, Dr. Hayward of Norwich, Vermont, advertised “Genuine Essence of Peppermint, Tansy, Gum-Hemlock, and Checkerberry.”[14] By this time, the term “genuine” was losing its connotation of British and was beginning to suggest quality and to affirm that the products were really what they claimed to be and were not adulterated with other substances.

The early history of American medicine is tied to the history of plant essences and patent medicines.[15] The term “patent medicine” is inexact. English medicines were first marketed in the eighteenth century by royal patent, but chemical patents did not come into use in the United States until the twentieth. Nostrums that claimed “patent” pedigrees eventually lost their proprietary associations and were manufactured and sold generally. A characteristic of these generic patent medicines was usually a distinctive container that made a medicine easily recognizable to consumers and a recipe often known to all merchants but not to consumers. Essence of peppermint was usually sold in special vials alongside patent preparations such as opodeldoc, balsam of life, and hot drops. As a result, historians sometimes inaccurately refer to peppermint essence as a patent medicine.

In the first half of the nineteenth century, physicians acquired their credentials by training as apprentices with practicing doctors or by attending three- to four-month-long medical lectures loosely affiliated with colleges such as Harvard, Yale, and Dartmouth.[16] In either case, the students became acquainted with a materia medica that had its roots in antiquity and wound its way tortuously through the writings of medieval alchemists and early modern natural philosophers. A germ theory of medicine was not firmly established until the final quarter of the nineteenth century, although scientifically minded physicians like Charles Knowlton of Ashfield, Massachusetts, and Oliver Wendell Holmes of Boston began publishing their observations and theories of contagion as early as the 1840s.[17]

The materia medica of the early nineteenth century contained a wild variety of substances, among which peppermint oil and essence were not only benign but also relatively efficacious. Before 1850, physicians routinely prescribed substances like calomel (mercury chloride), antimony, and cantharides (Spanish fly), despite mounting evidence of their toxicity. Debate over medicines gradually expanded from specialist venues such as the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal into a public backlash against dangerous and ineffective prescriptions and other heroic treatments such as bloodletting. Frustrated with their physicians, many patients turned to Thomsonian herbalists, hydrotherapists, homeopathists, electerizers, and a tradition of do-it-yourself medicine that was as old as the republic.[18] Peppermint was one of the few medicines upon which orthodox physicians and their critics agreed.

Edinburgh physician William Buchan’s Domestic Medicine, first published around 1772, spread rapidly through the English-speaking world and was the model for many home health manuals. Buchan mentioned peppermint several times and suggested peppermint water was preferable to brandy for colic and other stomach ailments.[19] Peppermint products became not only key ingredients in many medicines prescribed by physicians but also components of every family’s home medical shelf.

In 1798, physician William Currie wrote a pamphlet on cholera in which he offered a dozen prescriptions for the various symptoms of the disease. Peppermint oil (“Minth Piper”) was a component of all.[20] The 1788 edition of The Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia Almanack and Ephemeris cited peppermint essence as a “Recipe for the Cure of the most excruciating Pain in the Region of the Stomach, attended with severe Griping.”[21] Edinburgh medical professor William Cullen’s two-volume Treatise of the Materia Medica, 1789, described “Mentha Piperita” as containing “more essential oil than any other species of mint.” There was no doubt, Cullen said, “of its answering the purposes of any other species of mint; and the water distilled from it is manifestly more immediately antispasmodic and carminative.”[22] In 1793, Isaiah Thomas’s Worcester edition of The Family Female Physician included dosage instructions for essence of peppermint and the recommendation that Peruvian Bark (quinine) should be administered in a glass of peppermint water.[23]

During the yellow fever outbreak in Philadelphia, William Currie’s Treatise on the synochus icteroides recommended: “Small doses of a cordial mixture composed of the oil of peppermint and compound spirits of lavender, may be taken until the sickness abates.”[24] Dr. Benjamin Rush’s Account of the Bilious Remitting Yellow Fever copied Currie’s peppermint prescription word for word.[25] In 1796, Samuel Hemenway’s Medicine Chests, with Suitable Directions described essence of peppermint as “good in pains of the stomach, colicky pains, attended with wind, in trembling and nervous complaints, and in sea sickness” and prescribed “20 or 30 drops” taken on sugar or in a cup of warm water.[26] In 1801, Samuel Stearns’s American Herbal; or Materia Medica, which many historians consider America’s first original herbal, listed peppermint as “a stimulant [that] restores the functions of the stomach, promotes digestion, stops vomiting, cures the hiccups, flatulent colic, hysterical depressions, and other like complaines.”[27] And in 1802, the Bee in Hudson, New York, carried an advertisement for “A few articles necessary for country life—such as, Rawson’s Bitters, Stoughton’s do. Essence of Lemon, Bergamot, Lavender, and Peppermint—Oil of Peppermint.”[28]

Physicians considered peppermint not only a valuable remedy in its own right but also an important additive to many medicines, whose properties would complement those of the other active ingredients while making the overall mixture more palatable and digestible. In 1807, Oram’s New York Almanac reminded its readers in its recipe for a “Cure for Dysentery” that “if a considerable portion of the essence of peppermint be added, it will be a valuable improvement of the medicine.”[29] In 1814, Connecticut publisher T. M. Skinner printed Howell Rogers’s fifty-eight-page manual On Essences and Their Use, which advised its readers on the uses and also the preparation of “a variety of tinctures and syrups.” Rogers described peppermint essence as a remedy that might be taken regularly “and repeated with safety.”[30] Practitioners and patients appreciated the fact that peppermint oil was safe at the dilutions used in essences. Many other remedies of the day, such as calomel and antimony, were highly toxic and unsafe even in the hands of doctors. Peppermint’s combination of effectiveness and relative safety made it a valuable addition to both the doctor’s bag and the farm family’s medicine shelf.

One of the most feared and hated adversaries of professional medicine in the early nineteenth century was Samuel Thomson, a self-taught herbalist from Alstead, New Hampshire. Although today Thomson’s treatments seem to have little basis in medical science, at the time they appeared effective. At the very least, unlike the doctors’ so-called heroic treatments Thomson’s herbal preparations had the virtue of not damaging the patient further, thereby allowing for natural healing. Thomson’s philosophy of medicine revolved around heat, based like some of the ideas of his contemporary physicians on Galen’s four humors. Thomson’s favorite herb for warming the patient’s inner system was lobelia (Lobelia inflata). His second line of defense consisted of “Cayenne, Peppermint, Pennyroyal, or any warm article to assist in raising the inward heat.”[31] Both mainstream physicians and their Thomsonian opponents had vials of peppermint essence on their shelves of favorite remedies.

Samuel Ranney, who would become the first peppermint king, grew up in Middletown while peppermint was becoming established as an important element of American medicine. The Ranney family, begun by a Scottish immigrant named Thomas Ranney, who was among the original proprietors of the Connecticut town, prospered as Middletown became the most important port between Boston and New York City. Middletown was the northernmost port on the Connecticut River open to ocean shipping, and its population in the year of Samuel’s birth exceeded that of New Haven and Hartford. Shipbuilding, the West India trade, and coastal trading had made Middletown wealthy, and steadily increasing property values made it possible for enterprising immigrants who arrived at the right time to leave the city with money in their pockets.

The euphemism “West India trade” refers to the sugar economy of Caribbean islands such as Barbados, based on the forced labor of enslaved Africans. Sugar was a native of Europe introduced to the Americas as part of the Columbian exchange. Although an ancient luxury, sugar became an item of mass consumption when the West Indies enabled “the links between colony and metropolis, fashioned by capital,” described by Sidney W. Mintz in his seminal commodity history, Sweetness and Power.[32] Repeated grinding and boiling of sugar cane produces table sugar, with the first boiling of the cane creating brown sugar and a by-product, molasses. A second boiling of this raw sugar (which in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was often done in Europe) produces white table sugar and a by-product called syrup. West Indian distillers turned molasses into rum, and Europeans distilled syrup with juniper berries to make gin.

But not all West Indian colonies produced rum. Saint Dominique, the French colony on the east side of Hispaniola that became Haiti, threw away its molasses or sold it to smugglers. The French government, in an attempt to protect its domestic wine industry, had outlawed the distilling of anything not made from grapes. And even on the English sugar islands there was enough molasses available to support an export market. Middletown became a center of rum distilling from Caribbean molasses.

According to historian William J. Rorabaugh, during the Revolutionary Era, British North Americans drank four gallons of rum annually per capita. That total is twice as much as all the alcohol modern Americans consume, and it does not count gin, hard cider, beer, ale, wine, brandy, and whiskey, all of which the colonists also consumed in substantial quantities.[33] Before the Revolution, the mainland colonies contained twenty-five sugar refineries and 140 rum distilleries. After the war, these numbers increased. Among the new suppliers was a distillery opened in Middletown that produced six hundred sixty-three-gallon hogsheads of rum per year through the early 1820s.[34]

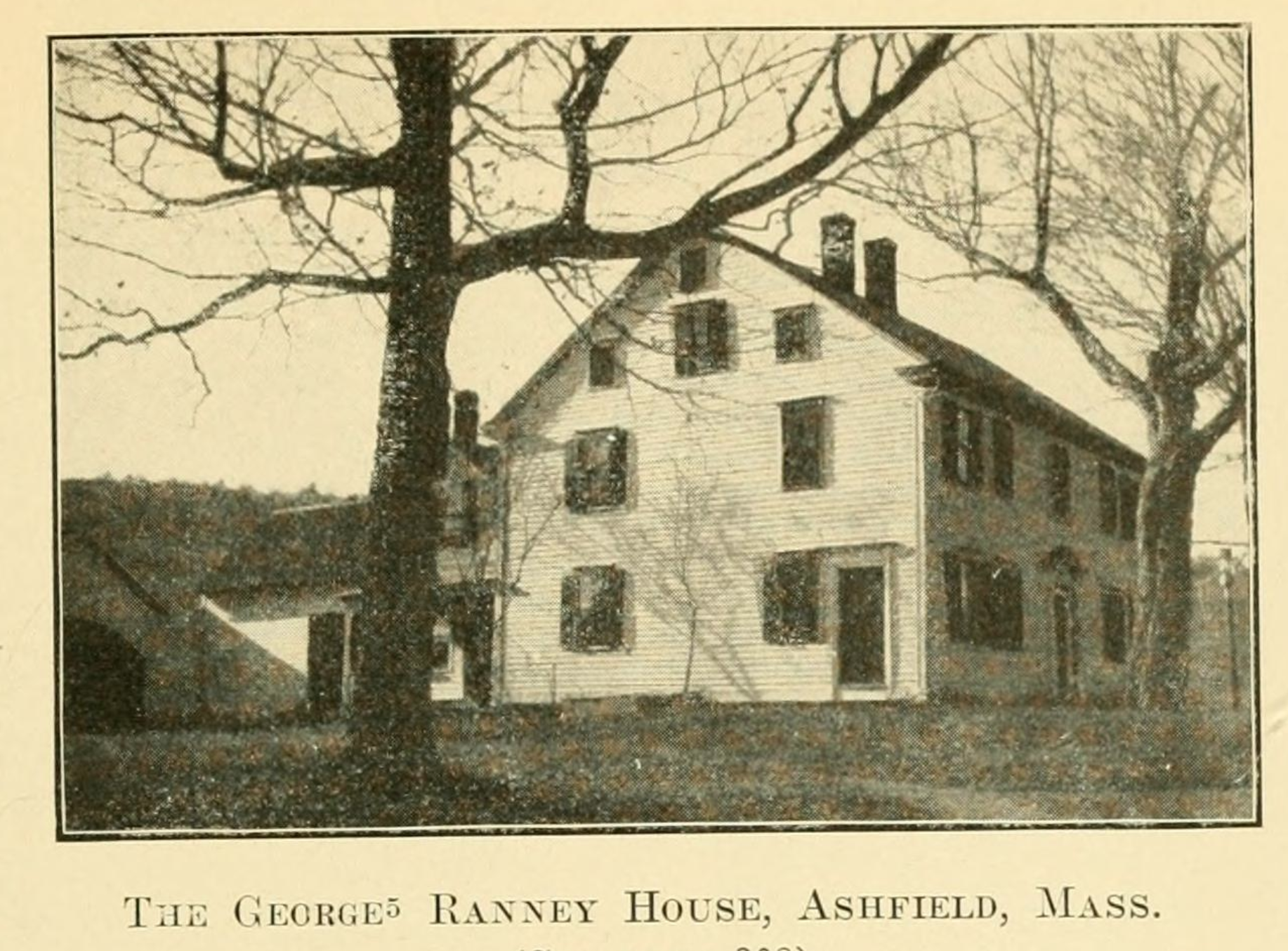

Thomas Ranney’s great-great-grandson George (whose father and grandfather were also named George) was born in the summer of 1746. “In early life,” a Ranney family genealogy reluctantly admits, “he was in the West India trade.”[35] The experience of George Ranney with Middletown’s triangle trade in molasses, rum, and slaves probably began in his youth, well before the American Revolution. It is not known whether he ever went to sea, but by his early thirties George had left the business and quit Middletown altogether. In 1771, he married Esther Hall, daughter of another Middletown founding family. The couple had eight children in the next nine years. The last child, also named George, was born in 1780, the year the family moved to Ashfield, Massachusetts. The senior George bought “a 100-acre farm, most of which was a forest, and built a log house.” Remembered as a short, stout man “of industry and perseverance,” George senior cleared the parcel with the help of his four sons, and in 1798 he built a two-story frame house that still stands today. George senior’s oldest son, Samuel Hall Ranney, was born in 1772 in Middletown. Samuel moved to Ashfield with this family as a young boy in 1780, but he seems to have returned to Middletown frequently. Samuel’s uncle Thomas Ranney and his cousin Roswell Ranney had remained in Middletown, but they moved to Ashfield when Samuel was twenty, in 1792. Two years later, Samuel returned to Middletown to marry Polly Stewart, a sea captain’s daughter from nearby Branford, Connecticut. Samuel’s younger brother Joseph also returned to Middletown in 1801, married a local girl, and remained in Connecticut, working in local quarries until 1818.

Returning regularly to Connecticut in the late 1780s and early 1790s, Samuel Ranney was probably exposed to the distiller’s craft there. Middletown’s rum distillery was owned by a relative on Samuel’s mother’s side, the merchant William C. Hall. In 1793, the general store of Ranney’s neighbor Selah Norton in Ashfield advertised “Old Jamaican Spirits” as well as “New England Rum” in the Hampshire Gazette.[36] It’s not difficult to imagine Ranney transporting Hall’s Middletown rum and barrels of Caribbean spirits to Ashfield and learning a bit about distilling in the process.

Samuel Ranney was unorthodox from a young age: a freethinker of sorts. The bride he returned to Connecticut to marry, Polly Stewart, was the illegitimate daughter of a privateer named William Stewart and a Middletown resident named Lucretia Braddock. Although reputedly descended from the Mayflower Braddocks, Lucretia never married William Stewart. When Stewart died in 1779 “in an engagement with the British at sea,” he left his estate to a different woman and family. But apparently Polly’s ancestry did not concern the sixth-generation descendant of one of Middletown’s founders. Samuel married Polly in 1794, and Lucretia’s legacy must have been a powerful one. Polly and Samuel’s first two children were named Lucretia and Braddock. Their second son was named William.[37]

Traveling between western Massachusetts and central Connecticut with cargoes of rum, Samuel Ranney would hardly have been able to avoid coming into contact with people growing and distilling peppermint. According to an undated western Massachusetts newspaper clipping held at the Ashfield Historical Society, “In 1934, when the former Richard Pritchard house in Lanesboro, almost 150 years old, was being repaired, several documents were discovered. One was a receipt dated Oct. 4, 1811, for 88 pounds, 14 ounces of peppermint oil valued at $440.”[38] This is consistent with local stories and with other documents, such as a December 1800 Pittsfield Sun advertisement placed by the Lanesboro brewer John Hart for a “Distillery & Brewery, One mile east of the Meeting House in Lanesborough, Where may be had, Beer of the best quality by the Hogshead, Barrel, or less quantity as may suit the purchaser. Also, Essence of Pepper Mint, American and English, warranted genuine, in patent vials, by the single, dozen, gross or thousand. Mint Cordial by the Gallon.”[39] Similarly, according to an 1885 history, around 1790 “at the Kitchen [a village in Lanesboro], Nathan Wood had a grist and a saw-mill, and a little later a distillery on the old Lanesborough road near the town line. . . . Peppermint was grown quite extensively and the essence manufactured.”[40]

Coming from Middletown, returning there regularly as a young man, and traveling in western Massachusetts gave Samuel Ranney all the exposure he needed to peppermint and distilling. Samuel and Polly established a farm adjacent to George Ranney’s land to the south, and in 1821 Samuel built a brick house that still stands beside Route 116 in Ashfield. Samuel began growing and distilling peppermint around 1812, and his brother George, who inherited their father’s house and land 1822, quickly turned his fields over to peppermint as well. It is likely that George and Samuel’s brother Jesse (who had the farm just north of George’s land) also planted peppermint.[41]

The town of Ashfield sits in the Berkshire foothills about twelve miles west of Deerfield. The 1879 History of the Connecticut Valley described Ashfield’s location as “well watered, though possessing no great waterpower. . . . The surface of the town is broken into hills and valleys, and contains but a comparatively small portion of arable land. Indian corn succeeds well, but English grain is of secondary quality. Wheat is seldom sowed.”[42] Ashfield’s farmers were unable to grow staple grains in commercial quantities and had no gristmill to grind them. They turned instead to peppermint, distilling, and commerce.

The town was difficult to reach, and its elevation extended and intensified the winters (and still does). When it was incorporated in 1765, it could be reached only by foot or on horseback over rough woodland trails. The first regular stage route, a private weekly mail service from Northampton via Whately, did not begin until 1789. In 1893, lifetime resident Henry Ranney noted that in its early years the town was “peculiar in its extremely isolated condition, for none of the towns adjoining it, on the north, south, east, or west, had received its name or even its first inhabitant.”[43] But its isolation did not result in its residents feeling remote from the outside world and its concerns. From their earliest days, Ashfielders were intimately engaged in political and religious struggles often characterized as being more central to urban areas. By the time Samuel Ranney arrived in Ashfield, the seemingly isolated town was rife with religious and economic conflicts of national importance. These conflicts would help shape the development of the Ranney family and the peppermint oil business the Ranneys built in Ashfield and later expanded to western New York and Michigan.

Early in the town’s history the first Ashfield settlers were joined by Chileab Smith and his family. Smith was a poor man from Hadley on the Connecticut River who had distinguished himself by siding with revivalist theologian Jonathan Edwards against Solomon Stoddard and his elite supporters, known as the River Gods. Smith settled his family in Ashfield in 1751, and he and his son Ebenezer quickly became notable Massachusetts Baptists. Religious differences exacerbated the wealth inequality among the settlers, driving a wedge between Ashfield residents. This social division was aggravated with the arrival of Israel Williams, the son of William “Hatfield” Williams, a wealthy, Harvard-educated River God and a relative of the Stoddard clan.[44]

Ashfield’s town history describes Williams as a man who “seemed unable to resist asserting himself from time to time.” In 1762 Williams and his fellow River Gods, many of whom were nonresident proprietors of Ashfield, called a Yale-educated “orthodox” minister to establish a Congregational Church in the town. The minister, Jacob Sherwin, was known for his “virulent opposition to [Baptist] separatists, [and] once ordained he busied himself preaching against the Baptists, and once even barged into one of their meetings and ordered them to disperse.”[45] The college in New Haven would provide several ministers over the years to support the conservative Congregationalists. Against them, the Baptists would appeal to eastern religious leaders, and ultimately to the king himself.

The town’s religious controversy was more than merely a contest of words. Until 1753, Massachusetts colonial law had exempted Baptists from attending or supporting the established church, which was Congregational. After his arrival in Ashfield, Israel Williams used his influence in Boston to get the law changed, allowing the new Congregational Church in Ashfield to tax all the town’s inhabitants. Chileab Smith went to Boston in 1769 to protest the “Ashfield Law,” carrying with him not only a petition from the town’s Baptist residents but also a “companion petition from a group of Ashfield Congregationalists suggesting, in Smith’s words, that ‘it is not all the other Society that would thus Oppress us.’” The second petition stated that most of the community had “no objection a Gainst the anabaptest societys Being set free from paying to the maintenances of the other worship which they Do not Belong unto.” Historian Mark Williams has suggested that the support Smith and the Baptists received from their Congregationalist neighbors “was a dangerous development for Israel Williams, for it set the non-resident proprietors apart from the majority on inhabitants in whose best interest they were supposedly acting.”[46]

The Ashfield Baptists called attention to the irony of the River Gods’ position, in town meetings, in Boston, and beyond. Following the Boston Massacre in March 1770, Smith and his supporters sent a “biting petition” to the Massachusetts legislature. Invoking the principles of the rebellious Sons of Liberty, the Ashfielders wrote: “No Taxation can be equitable where such Restraint is laid upon the Taxed as takes from him the Liberty of <sc>GIVING</sc> his Own Money Freely.” The conflict began to attract regional attention and was even noticed in Philadelphia. Ezra Stiles, Connecticut’s delegate to the Continental Congress and later president of Yale, noted in 1774 a degree of “coolness” in Congress toward the Massachusetts delegation “because of the persecution of the Baptists.”[47]

The leaders of the Congregational Church were undeterred, in spite of acting without the enthusiastic support they had claimed from most of the parish. The churchmen seized four hundred acres belonging to the Baptists and sold the land at public auction. The properties consisted of “mowing lands, winter grain, orcharding, one dwelling house of a poor man’s, and [the Baptists’] burying place,” and they were disposed of “for a very small part of their value.”[48] When early America’s leading Baptist minister, Isaac Backus, described the events in Ashfield in his Church History of New England, he concluded, “This plainly discovers what wickedness is the consequence of supporting religious ministers by force.”[49] In addition to his high-handed treatment of his neighbors, the selection by Israel Williams of Jacob Sherwin as pastor of the new Congregational Church was also problematic. The new pastor turned out to be an autocrat, and the church was “constantly distracted by disciplinary issues that drove a wedge between Sherwin and many of his parishioners.” To make matters worse, in a town where several of the original settlers were formerly enslaved blacks and poor whites who had endured indenture, Sherwin was a slave owner.[50]

Thomas Hutchinson, the royalist governor of the Bay Colony, forwarded the Ashfield Baptists’ petition to London, perhaps thinking it would discredit the revolutionary cause. King George III’s Privy Council ruled in favor of the Baptists, and the king decreed their property should be restored to them. This action of the Crown caused Ashfielders to ask some pointed questions when Boston’s Committees of Correspondence began soliciting support for their rebellion against the monarchy that became the American Revolution. Chileab Smith called the Sons of Liberty “Sons of Violence,” and his son Ebenezer denounced them from the pulpit and said “they were calling themselves sons of liberty and were erecting their liberty poles about the country, but they did not deserve the name, for it was evident that all they wanted was liberty from oppression that they might have the liberty to oppress.”[51]

During and after the Revolution, Ashfielders remained jealously protective of the freedoms for which they had fought. In October 1776, a town meeting rejected the idea that the state legislature should be permitted to rewrite Massachusetts’s Constitution without popular supervision and resolved “to Opose the Least Apearanc of them Old Tiranical Laws taking place again.” The majority of Ashfielders continued to push for an interpretation of liberty that was much more egalitarian than the society envisioned by the River Gods and their elite allies in Boston. In October 1774 the town voted “to Give Liberty for all men to vote in this meeting that are town Inhabitence that are twenty one years old and upward,” at a time when 40 percent of Ashfield’s taxpayers did not meet the property limits required for voters. And in October 1779 the Ashfield town meeting instructed the town’s delegates in Boston to advocate a “Legislative Court” to govern the state. Its members would be chosen by “ye Several Towns & . . . every Man being 21 years of Age who has not by his own Act forfeited his Freedom Shall be accounted free and have a Right to Vote.” Finally, beginning a long tradition of abolitionism, Ashfielders declared that even slaves should vote. And they stated that the legislature’s “Business shall be to protect all Persons in ye free Enjoyment of their religious Sentiments So far as they are good and peacibul Inhabitants.”[52]

When the Ranney family relocated from Connecticut to Ashfield in 1780, they discovered a town that held fast to its vision of liberty in spite of worsening economic conditions. At a 1783 town meeting, residents denounced taxation without representation and resolved: “We will not pay the five & twenty shilling State Tax on the pole Nor no other State Nor County Tax or Taxes is or may be Assessed upon the Town of Ashfield until we are informed by Genl Cort or Some other Authority the perticular use the said Money is Designed for.” To prevent militia officers being called to use their authority to enforce the taxes, the meeting called on the town’s officers to “resine their Commissions.” Although it has been traditional to characterize the “regulators” of Shays’ Rebellion as debtors, peasants, and poor Revolutionary War veterans angry over scrip speculation, Mark Williams has observed that the regulators of Ashfield were the town’s 1776 militiamen, acting as “the executive arm of a whole town in rebellion.” The townspeople’s continuing “stream of objections to the republicanism of the eastern elite,” Williams concludes, “contain a bold foray into a radical political culture that was neither traditional nor peasant-minded.”[53] Ashfield residents, far from feeling cut off from the religious and political controversies of their day, thrust themselves into the forefront of national and even international issues.

Among Ashfield’s regulators in Shays’ Rebellion were brothers Samuel and Lamberton Allen. Cousins of Vermont’s heroes and leaders of the Green Mountain Boys, Ethan and Ira Allen, Samuel and Lamberton had arrived in Ashfield around 1770 from Deerfield. Samuel was a lieutenant in the Revolution who had reenlisted three times and captain of the company that marched from Ashfield to aid in Daniel Shays’ harassment of foreclosure courts and attack on the Springfield armory. The Allen brothers appear often in town records, but they were disfranchised for refusing to accept official pardon, and their names are conspicuously absent from the list of those who took the oath of allegiance following Shays’ Rebellion. Samuel was apparently a bit eccentric and was remembered by Ashfield residents who had known him as “Barefoot Allen.” He and Lamberton moved to Grand Isle, Vermont, in 1780 after selling their mostly wooded hundred-acre “farm” to George Ranney.[54] Ranney took advantage of the opportunity to buy a flat, well-watered parcel when the Allens decided to move to a territory even more radical than Ashfield (Vermont did not become a state until 1791). Ranney’s son Samuel continued the Allens’ tradition of leadership and freethinking when he introduced peppermint to Ashfield and later helped move the peppermint industry west.

In the next chapter, we examine the history of Ashfield’s stills, the essence-peddling business run by the Ranneys and their friends, the development of a wholesale peppermint oil market, and the expansion of the Ranney family across the western frontier.

- Some of the newspapers held by the American Antiquarian Society featuring advertisements for peppermint products include Massachusetts: Boston Chronicle 1768, 1770; Boston Evening Post 1769; Boston News Letter 1769, 1773; Boston Post Boy 1773; Columbian Centinel 1790, 1798; Daily Advertiser 1789; American Herald 1784, 1785; Hampshire Gazette 1788, 1800; Hampshire Chronicle 1790, 1791; Hampshire Herald 1784; Herald of Freedom 1789; Independent Chronicle 1783, 1784, 1786; Independent Ledger 1784; Massachusetts Gazette 1787; Massachusetts Mercury 1798; Massachusetts Sentinel 1789; Massachusetts Spy 1774; Moral and Political Telegraph 1796; Salem Gazette 1784, 1785, 1795; Salem Mercury 1788; Western Star (Stockbridge) 1795; Connecticut: Connecticut Journal 1774, 1783, 1785, 1791; Connecticut Gazette 1788, 1796; Connecticut Courant 1791; Bee (New London) 1798; Litchfield Monitor 1791; Norwich Courier 1797; American Mercury 1784, 1785, 1797; New Haven Gazette 1784, 1785; Delaware: Delaware Gazette 1790; Georgia: Georgia Gazette 1769, 1790; Augusta Chronicle 1796; Columbian Museum 1796; Maryland: Maryland Journal 1784, 1785, 1786, 1787, 1790; Maryland Gazette 1790; Baltimore Evening Post 1792; Federal Gazette 1796; New Hampshire: New Hampshire Gazette 1784, 1789, 1795; New Hampshire Spy 1791; New Jersey: New Jersey Journal 1790; New Jersey Political Intelligencer 1784; Burlington Advertiser 1790; New York: New York Mercury 1763, 1771; New York Gazette 1764, 1765, 1776, 1777, 1778, 1779, 1782, 1783, 1790, 1791, 1792; New York Journal 1768, 1772, 1773, 1785; New York Morning Post 1784, 1785, 1786, 1788, 1789, 1790; New York Packet 1784, 1791; Albany Gazette 1791, 1798; American Spy (Lansingburgh) 1792; Daily Advertiser 1786, 1791, 1792, 1796; Diary 1792; Independent Journal 1784; Royal American Gazette 1777, 1778, 1779, 1781; Royal Gazette 1778, 1781, 1782; North Carolina: North Carolina Journal 1792; Pennsylvania: Carlisle Gazette 1787, 1792; Pennsylvania Chronicle 1768, 1772; Pennsylvania Gazette 1768, 1770, 1771,1772, 1787; Pennsylvania Packet 1772, 1773,1774, 1778, 1783, 1784, 1785, 1787, 1788. ↵

- “Just Imported from London,” New York Mercury, 12/19/1763. ↵

- John Ray, Synopsis Methodica Stirpium Britannicarum in Qua Tum Notae Generum Characteristicae Traduntur, Tum Species Singulae Breviter Describuntur: Ducentae Quinquaginta Plus Minus Novae Species Partim Suis Locis Inferuntur, Partim in Appendice Seorsim Exhibentur: Cum Indice & Virium Epitome (London: Sam. Smith, 1696), 124. ↵

- Ibid., 126. ↵

- Ibid., 126. ↵

- Robert Harris, Pennsylvania Chronicle and Universal Advertiser, 5/30/1768. ↵

- Richard Speaight, Royal American Gazette, 9/24/1778. ↵

- Atwood, New York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, 12/28/1778. ↵

- John Joy, Independent Chronicle and Universal Advertiser, 6/17/1784. ↵

- Hampshire Herald, 10/19/1784. ↵

- George B. Griffenhagen and James Harvey Young, Old English Patent Medicines in America (Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1959). ↵

- United States Chronicle: Political, Commercial, and Historical, 5/4/1797. ↵

- Eastern Argus, 10/23/1806. ↵

- Dr. Hayward, Pittsfield Sun, 9/21/1811. ↵

- Olive R. Jones, “Essense of Peppermint: History of the Medicine and Its Bottle,” Historical Archaeology 15, no. 2 (1981). ↵

- Loosely affiliated medical lectures were often associated with established institutions but conducted off campus and held at arm’s length by conservative college presidents like Timothy Dwight at Yale and the trustees of Harvard and Dartmouth. William Henry Welch, “The Relation of Yale to Medicine,” Science 14, no. 361 (1901); Oliver S. Hayward and Constance E. Putnam, Improve, Perfect and Perpetuate: Dr. Nathan Smith and Early American Medical Education (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 1998). ↵

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Medical Essays, 1842–1882 (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1893; Dan Allosso, An Infidel Body-Snatcher and the Fruits of His Philosophy: The Life of Dr. Charles Knowlton (Minneapolis: SOTB, 2013). ↵

- John Duffy, From Humors to Medical Science: A History of American Medicine (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993). ↵

- William Buchan, Domestic Medicine; or, the Family Physician: Being an Attempt to Render the Medical Art More Generally Useful, by Shewing People What Is in Their Own Power Both with Respect to the Prevention and Cure of Diseases. Chiefly Calculated to Recommend a Proper Attention to Regimen and Simple Medicines. By William Buchan, M.D. To Which Is Added, Dr. Cadogan’s Dissertation on the Gout (New York: John Dunlap, 1772). ↵

- William Currie, “Of the Cholera,” 1798. ↵

- William Goddard, The Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia Almanack and Ephemeris, for the Year of Our Lord, 1788 (Philadelphia: Goddard, 1787). ↵

- William Cullen, A Treatise of the Materia Medica by William Cullen . . . In Two Volumes (Philadelphia: Joseph Crukshank, 1789). ↵

- Alexander Hamilton, The Family Female Physician: Or, a Treatise on the Management of Female Complaints, and of Children in Early Infancy (Worcester: Isaiah Thomas, 1793), 335, 347. ↵

- William Currie and Thomas Mifflin, A Treatise on the Synochus Icteroides, or Yellow Fever as It Lately Appeared in the City of Philadelphia: Exhibiting a Concise View of Its Rise, Progress and Symptoms, Together with the Method of Treatment Found Most Successful: Also Remarks on the Nature of Its Contagion, and Directions for Preventing the Introduction of the Same Malady, in Future (Philadelphia: Thomas Dobson, 1794). ↵

- Benjamin Rush, An Account of the Bilious Remitting Yellow Fever, as It Appeared in the City of Philadelphia, in the Year 1793 (Philadelphia: Thomas Dobson, 1794), 220. ↵

- Samuel Hemenway, Medicine Chests, with Suitable Directions: Prepared by Samuel Hemenway, at His Shop in Essex Street, Opposite Union Street, Salem (Salem, Mass.: W. Carlton, 1796). ↵

- Samuel Stearns, The American Herbal, or Materia Medica: Wherein the Virtues of the Mineral, Vegetable, and Animal Productions of North and South America Are Laid Open, So Far as They Are Known; and Their Uses in the Practice of Physic and Surgery Exhibited; Comprehending an Account of a Large Number of New Medical Discoveries and Improvements, Which Are Compiled from the Best Authorities (Walpole, Mass.: David Carlisle, 1801), 9. ↵

- Bee, 12/28/1802. ↵

- Abraham Shoemaker, Oram’s New-York Almanac, for the Year of Our Lord, 1807 (New York: James Oram, 1806). ↵

- Howell Rogers, On Essences and Their Use and, on the Method of Preparing and Taking a Variety of Tinctures and Syrups (Colchester, Conn.: T. M. Skinner, 1814), 18. ↵

- Samuel Thomson, A Narrative of the Life and Medical Discoveries of Samuel Thomson (Columbus, Ohio: Jarvis, Pike, 1833), 77. ↵

- Sidney Mintz, Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (New York: Penguin Books, 1985), 116. ↵

- W. J. Rorabaugh, The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979). ↵

- Charles Collard Adams, Middletown Upper Houses; a History of the North Society of Middletown, Connecticut, from 1650 to 1800, with Genealogical and Biographical Chapters on Early Families and a Full Genealogy of the Ranney Family (New York: Grafton Press, 1908), 16. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Mark Williams, The Brittle Thread of Life: Backcountry People Make a Place for Themselves in Early America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 209. ↵

- Adams, 261. ↵

- Ashfield: Richard V. Happel, “Peppermint Oil,” ↵

- Phinehas Allen, Sun, 12/9/1800. ↵

- Ellen M. Raynor, Emma L. Petitclerc, and James Madison Barker, History of the Town of Cheshire, Berkshire County, Mass (Holyoke, Mass.: C. W. Bryan, 1885), 75. ↵

- Williams, 218. ↵

- L. H. Everts and Co., History of the Connecticut Valley in Massachusetts: With Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Some of Its Prominent Men and Pioneers (Philadelphia: L. H. Everts, 1879). ↵

- Ashfield: H. S. Ranney’s Centenary Address, 1893. ↵

- Williams, 249; William G. McLoughlin, “Ebenezer Smith’s Ballad of the Ashfield Baptists, 1772,” New England Quarterly 47, no. 1 (1974), 140. ↵

- Williams, 272, 287. ↵

- Ibid., 295. ↵

- Ibid., 297, 304; Frederick G. Howes, History of the Town of Ashfield, Mass. Volume I (West Cummington, Mass.: Wm. G. Atkins, printer, 1910), 75 ff. ↵

- Howes, 10. ↵

- Isaac Backus, Church History of New England, from 1620 to 1804: Containing a View of the Principles and Practice, Declensions and Revivals, Oppression and Liberty of the Churches, and a Chronological Table (Philadelphia: Baptist Tract Depository, 1839), 101, 193. ↵

- Williams, 304. ↵

- Ibid., 303. ↵

- Ibid., 320, 330, 335. ↵

- David P. Szatmary, Shays’ Rebellion: The Making of an Agrarian Insurrection (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1980); Leonard L. Richards, Shays’s Rebellion: The American Revolution’s Final Battle (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002); Williams, 342, 349–50. ↵

- The 1800 U.S. Census page for the township of Middle Hero on Grand Isle includes Lamberton Allen, Lamberton Allen Jr., Samuel Allen, Ebenezer H. Allen, and Enoch Allen, as well as Samuel Belden, a member of the Belden/Belding family of Deerfield and Ashfield that was also prominent in the peppermint oil business. Both Lamberton Allen and his brother Enoch were married to Beldings. Howes. ↵