1 “Previously in World History”

Modern World History is often listed as “World History II” in college catalogs. This means there is a “World History I” that describes changes in the human experience on earth, the development of major civilizations and cultures, and the ways human populations around the world interacted from the beginnings of recorded history until roughly the beginning of the “Modern” era. Some of the readers of this text may be very familiar with the earlier history covered in the previous course. Others may be less aware of the major events that led to and “set the scene” for the modern world. And even those who have studied ancient and medieval world history may not be familiar with the particular events that form the background for the stories we’ll focus on in this text. Understanding Modern World History occasionally requires a bit of background that will help contextualize the material we will cover. This chapter will cover that background.

“Agricultural Revolutions”

The human experience on earth began over a million years ago, and unfortunately for most of that time people did not have written language. Since there are no records available of the types from which historians usually build their picture of the past, we have been forced to rely on information provided by scholars such as archaeologists, anthropologists, geneticists, and other specialists for the data that informs our histories. And because the science supporting these fields has advanced rapidly in recent years, our understanding of this prehistoric period has also changed – sometimes abruptly.

One of the elements of human prehistory where our understanding has changed radically is the development of agriculture. It seems intuitively obvious that people could not “advance” and develop “civilizations” until they were able to stop hunting and gathering and settle down to begin farming. Anthropologists who study present-day foraging people often remark on the egalitarian nature of their communities. There is usually not a division of people into rich and poor, “haves” and “have-nots”. But this is usually because everyone is equally poor; at least from the perspective of the anthropologists, who are usually from richer, more “developed” nations with universities and research grants. In any case, the typical story of prehistory is that it was only when humans were able to store surpluses of staple grains like wheat and rice that they were able to turn away from the daily search for food and give some attention to building cities and developing writing, art, and all the things we think of when we say civilization and culture. Among these, most anthropologists admit, are social hierarchy, inequality, taxes, slavery, and arbitrary power held by some people over others.

Recent archaeology, however, suggests that the transition from free and egalitarian hunter-gather societies to city-states, kingdoms, and empires of rulers and ruled was not inevitable and did not happen immediately when people began farming. In the first place, foraging people of today are usually trying to support themselves by hunting and gathering on some of the least productive land in the world, because all the better spots have been taken by more powerful modern neighbors. This would not have been the case in ancient times and people would have been able to do their hunting and gathering in places that would have produced rich rewards. Archaeologists have found many sites where people who were not farmers built cities and even monumental architecture. Interestingly, newly-published research argues that Stonehenge in England was built by people who had been farmers, but gave it up to be sheep and cattle herders up to a thousand years before they built the monument.(1 Chris Stevens and Dorian Fuller, “Did Neolithic Farming Fail? The Case for a Bronze Age Agricultural Revolution in the British Isles.” Antiquity 86 (333): 707-22, Cited in Graeber and Wengrow, The Dawn of Everything, 104.)

There are also many newly-discovered ancient cities where palaces, royal tombs, or other evidence of social hierarchy are nowhere to be found and the homes that people lived in were very similar with very little indication of wealth and poverty. Some of these were cities of hunter-gatherers or mixed hunting and horticulture, but some were places where the people had shifted to full-time farming and still avoided falling into kingdoms and empires for centuries or even millennia. This has come as a surprise to many historians and a strong indicator that farming and population growth did not inevitably have to lead to the results we live with today.

Question: Why is it important that shifting from foraging and hunting to farming did not immediately and inevitably lead to hierarchical societies like kingdoms and empires?

Agriculture itself was once believed to have developed in the Middle East at sites such as Jericho and Mesopotamia six or seven thousand years ago, where the ancestors of modern Europeans were usually credited with the invention of farming. More recently, responding to growing evidence of prehistoric farming in Africa, India, and China, some scholars suggested agricultural techniques may have developed more or less independently in several regions of the world. But it was difficult to imagine how such parallel development could have occurred, with people in different parts of the world not only making the same basic discoveries about cultivating plants, domesticating animals, and selectively breeding staple crops; but making them pretty much simultaneously. Even more recently, scientists have begun to suspect that many of the techniques that led to farming are much older than they had imagined and that some of the confusion over agriculture’s beginnings may reflect the difficulty of finding archaeological evidence, since plant materials decay in the ground much more quickly than arrowheads and stone spear points. And some have suggested we may have been thinking about agriculture wrong.

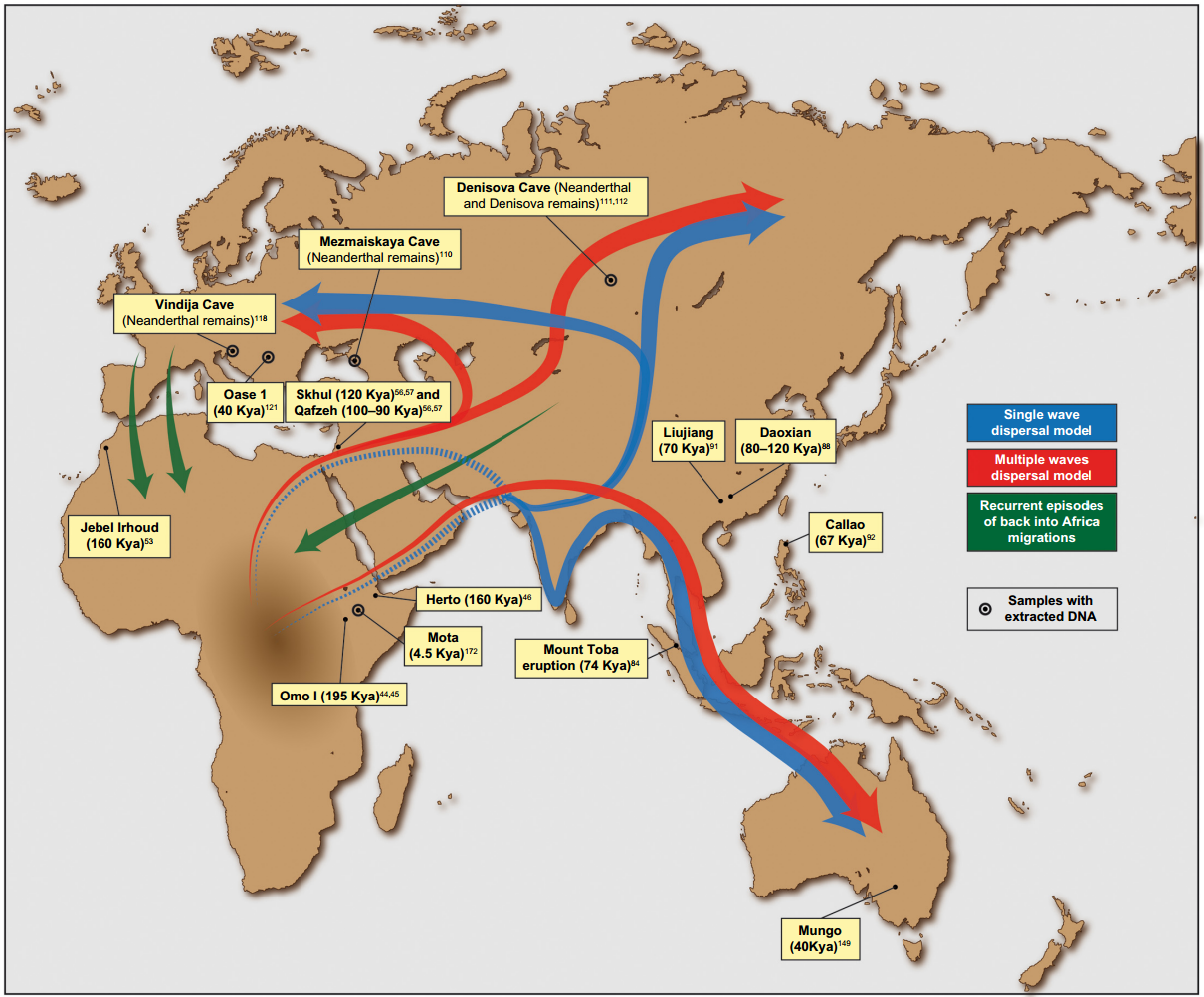

It now seems likely that agriculture began in a very gradual process that goes back much farther than we had once believed. Humans as a species began in southern Africa about 250,000 years ago and after a population crisis about 150,000 years ago during the ice age before the most recent one, modern humans seem to have left Africa between 100,000 and 80,000 years ago. They were not the first members of the human family that left Africa: Homo erectus, Neanderthals, and Denisovans all lived in Europe and Asia, using fire and stone tools, until they were displaced by this new wave of Homo sapiens leaving Africa. In many parts of the world, replacement of earlier humans with Homo sapiens does not seem to have been completed until the advent of the most recent ice age.

In the early millennia of their spread across the connected continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia, modern humans lived mobile lives as hunter-gatherers. According to archaeologists, many left many traces of their presence in the area north of the Black Sea in Eastern Europe from about 80,000 to about 50,000 years ago. Although they may have favored certain locations for long periods of time, ancient people were forced to follow the herds they hunted and to seek new food sources when conditions changed. Climate changed very slowly, but the cycle of glaciation was a factor in human development; especially the most recent ice age which began about 36,000 years ago and lasted until about 11,000 years ago. Like previous glacial periods, this ice age displaced both animal and human populations, possibly creating the conditions that allowed Homo sapiens to out-compete Neanderthals for food in the narrow strip of southern Europe that was free of ice. The ice age also allowed some people to migrate to the Americas, as we will see.

Cultivating plants probably began when hunter-gatherers began favoring valuable foods and medicines, weeding around them to help them grow larger and make them easier to reach. At some point, people discovered that seeds dropped on the ground or thrown into rubbish heaps sprouted into new plants. People probably began planting or transplanting their favorites closer to home, so they would not always have to go far, looking for food. This horticulture or part-time farming may even have begun before these ancient humans began to spread from the Black Sea area westward into Europe and east into Asia, which would explain the seemingly coincidental parallel development of farming across much of the globe. Various regions may have each developed their distinctive versions of what we now recognize as agriculture from a deep pool of common techniques.

Wheat was an improved form of a grass discovered in a region we call the fertile crescent, stretching from the Persian Gulf to the eastern Mediterranean. As cultivation spread and surpluses of grain were produced, civilizations like those of Egypt and Mesopotamia (today’s Iraq) rose between 6,000 and 5,000 years ago. About the same time (possibly a bit earlier) residents of the Pearl River estuary in what is now China began cultivating rice in flooded fields called paddies. The three other staple food crops of the modern world (corn, potatoes, and cassava) were developed between 9,000 and 7,000 years ago by natives of the Americas, as we will discuss below.

Although the sequence of events was not uniform and agriculture did not always mean an immediate transition from nomadic hunting and foraging groups to more complex societies based on agriculture, often the specialization and segmentation of work grain surpluses allowed, created an opportunity for people to develop sedentary cultures, establish governments, invent writing and number systems, and build hierarchal social systems able to erect impressive structures, defend (and sometimes expand) their borders, and create art, literature, philosophy, and music. This was not the only way these elements of civilization could be or were created; but enough of these cultures became large enough and left enough evidence at the very beginning of civilization that historians believed this explanation for a long time. We will now look briefly at the ancient societies of Africa, Europe, Asia, and the Americas to prepare for our coverage of them in the early modern period in the next few chapters.

Questions for Discussion

- Is it significant that historians must rely on information from other fields like archaeology to tell the story of the ancient world?

- Why does it matter where agriculture first developed?

- Does considering human migrations in the deep past affect your opinions on race and ethnicity?

Ancient Kingdoms of North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean

The ancient dynasties of the Egyptian empire developed along the Nile beginning around 3100 BCE, built on the wheat surpluses made possible by the annual flooding of the Nile River. Farming began in the region around 5000 BCE, and towns and cities thrived along the Nile for two thousand years before the rise of empire. The most visible and lasting monuments of the Egyptian empires are the pyramids of Giza, built between 2600-2400 BCE to serve as burial tombs for several emperors. The Egyptian empires existed for nearly 2,300 years before being conquered, in succession, by the Assyrians, Persians, and Greeks between about 700 BCE and 332 BCE.

The societies of ancient Greece, particularly in Athens, directly influenced culture and intellectual life in Europe and the Middle East to the present day. Greek dramas and tragedies continue to be studied and performed; Pythagoras’ mathematical discoveries are still taught in schools; and the thinking of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle are the basis for Western philosophy and political science today. The word “democracy” comes from these ancient Greeks, although the most famous example, Athens, did not necessarily operate in a way we would consider particularly democratic. Greek ideas and culture were adopted by the Romans and spread throughout their empire—in fact, many Greek gods became Roman gods under different names.

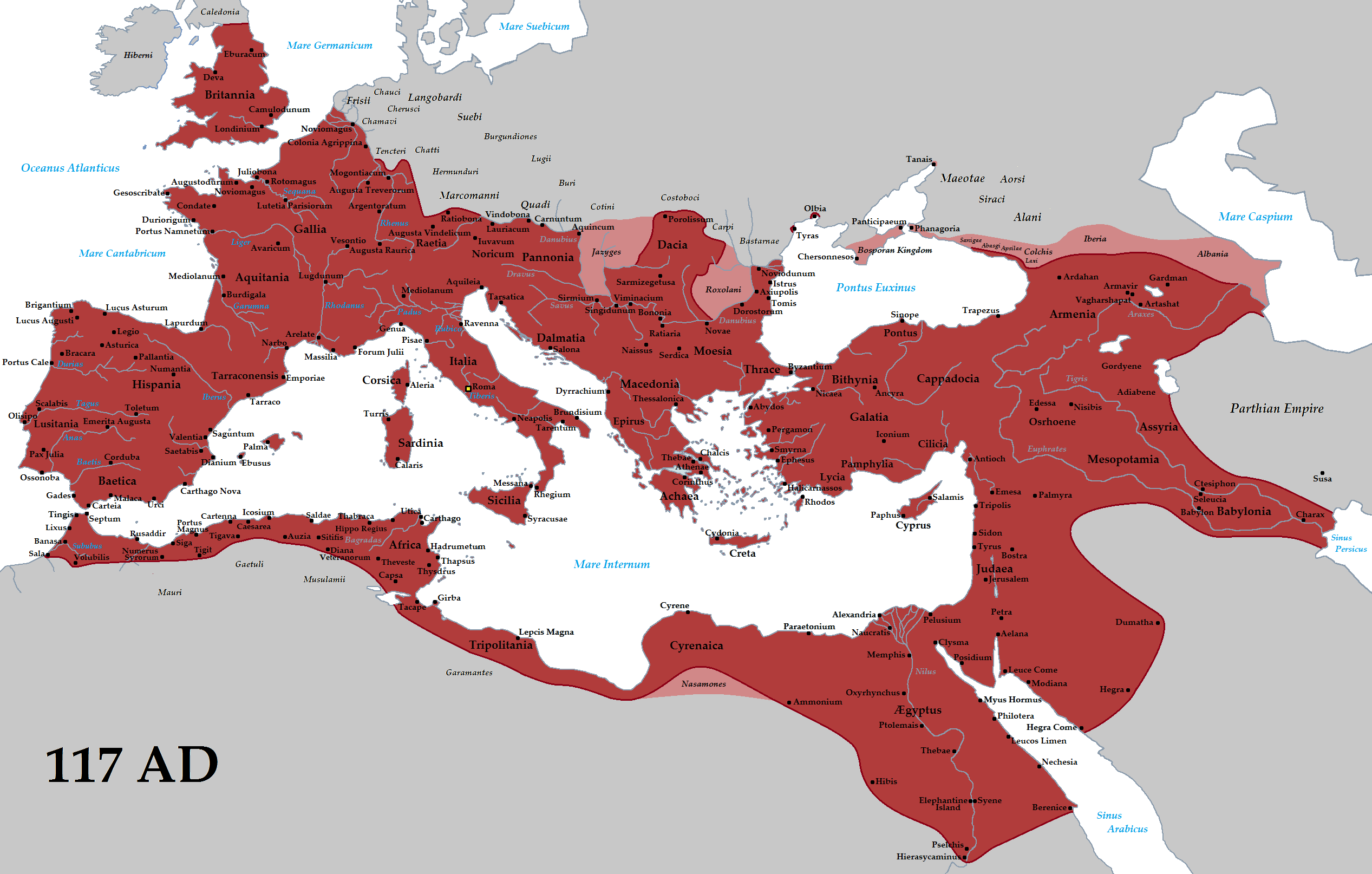

Ancient Rome was a republic for nearly 500 years, expanding its territory from the city of Rome on the western coast of the Italian peninsula to nearly all the lands surrounding the Mediterranean Sea, including the former Greek and Egyptian empires and even England. The Romans spread their language and their Latin alphabet to western Europe in particular. After a period of political crisis, the Republican government was replaced with an Emperor under Caesar Augustus in 27 BCE. But it should be noted that nearly all the territory that became the Roman Empire was conquered before the shift from Republican to Imperial rule.

The Egyptian, Greek, Assyrian, Persian, and Roman empires all encountered the Hebrew people, who briefly maintained their own independent kingdom of Israel around 1000 BCE. The Hebrew prophet Moses, apparently influenced by spiritual ideas from the various societies the Hebrews had interacted with, developed the concept of only one god for his people. Moses’ monotheism was an unusual innovation in an era when nearly all societies worshipped several gods and most honored the gods of other cultures. The Ten Commandments and the laws and regulations attributed to Moses in the Torah not only formed the basis of Judaism, but also of Christianity and later Islam—all religions which restrict worship to a single god.

Shortly after the Romans conquered the region of Israel, a Jewish thinker named Jesus of Nazareth, apparently began preaching a new more peaceful and inclusive religion of salvation. Although Jesus’ life and death is not recorded in contemporary documents, the same can be said about nearly everybody who lived in that era, so it is difficult to verify or disprove details of his life or death. According to Christian tradition, Jesus’ message was too radical for the Jewish and Roman establishment and he was turned over by enemies to the rulers, who crucified him in approximately 33 CE. His followers, led especially by Paul (said to have never met Jesus), preached that Jesus had been resurrected and was the Son of God. These Jewish believers in the Christ invited Gentiles (people who were not Jews) to join the faith, which expanded beyond Judaism and became Christianity. The new religion was especially embraced by slaves in the Roman Empire who were attracted to the promise of forgiveness, of a single, all-powerful God’s unending love, and of eternal life after death. The Romans saw the new religion as a challenge to state religious authority and were offended that adherents of the new faith refused to also worship Roman gods.

In 330 CE, the Roman Emperor Constantine banned persecution of Christians, and by 400 CE, Christianity had replaced the worship of Rome’s traditional gods and goddesses as the state religion of the Empire. Because Constantine embraced the new faith, the Roman Catholic Church is the most direct descendent of the Roman Empire. The Pope, leader of the Catholic Church, still lives in Rome, and the vestments of Catholic priests are similar to those worn by fourth-century Roman officials.

Questions for Discussion

- On what types of historical evidence do you think references to people such as Moses, Jesus, and Muhammad are based? How might these sources differ from the archaeological sources mentioned previously?

- How do the cultures of ancient Europe continue to influence life in the modern world?

The Eastern Roman Empire and the Fall of Rome

Constantine moved the capital of the Roman Empire to a second imperial capital in 330 CE. Byzantium, which he renamed Constantinople, was a powerful fortified city controlling the Bosphorus Strait that connects the Black Sea to the Mediterranean. The city of Byzantium was already a thousand years old when Constantine moved there. It served as the eastern administrative center of the empire and continued using Greek, rather than Latin, as its official language. A somewhat separate Christian church developed in this Greek part of the empire, based on the idea that the different archbishops controlled spiritual matters as a group, and that the Pope in Rome was only another archbishop, equal to the others. After 1000 CE, Catholics in the west and the Greek Orthodox in the east split from one another.

During the fifth century CE, Germanic tribes from northern Europe began recovering their territories that had been conquered by the Roman Empire. In the past, some historians described this as a “barbarian invasion” of the Roman Empire. In addition to reclaiming their ancestral lands, some of the Germanic peoples expanded into territory controlled by Rome as they fled from Attila the Hun and other invaders from Asia. Eventually, the city of Rome itself fell to the so-called “barbarians” in 476 CE. Western Europe was divided up among various Germanic tribes and regional chieftains. But although the central authority of the empire had ended the Roman Catholic Church remained strong. Over the next 500 years, Christianity spread throughout the region and was embraced by local and regional rulers. The Church preserved much of the culture of the Roman Empire, including its language, Latin, which was used in Catholic liturgies, masses, and ceremonies until 1965.

Germanic languages were transformed through their contact with Latin speakers. The English language is a good example of both Germanic and Latin influences. Consider how time is measured: the months of the year are all from the Roman calendar, with the first six months named after Roman gods, and July and August named after the early emperors Julius Caesar and Caesar Augustus, who had also been deified into the Roman pantheon. The remaining months are ordinal numbers seven through ten—although in a confusing change, the Catholic Church decided to begin the calendar in January, making “December” the twelfth month instead of the tenth. The days of the week, however, reveal both Latin and Germanic influences: Saturday, Sunday, and Monday come from the sacred Roman orbs in the sky—Spanish, French and other more Latin languages continue in this vein for the other four days, but not English, which honors the Germanic deities Tieu, Woden, Thor, and Frija for the remainder of the week.

The Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium) lasted for nearly another 1000 years after the fall of Rome. You can tell which European peoples were converted by Catholic missionaries and which were proselytized by Orthodox preachers by looking at their alphabets—Russia, Ukraine, and Bulgaria, for example, use the Greek-based “Cyrillic” alphabet, while western European languages use a version of the Latin alphabet.

Islam and Its Influence

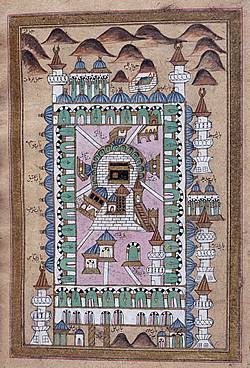

In 610 CE, an Arabian merchant named Muhammad began preaching and organizing a new religion, Islam, in the region of Mecca. Believers declared Muhammad was a Prophet and his teachings, later gathered in a book called the Quran, built upon Judaism and Christianity. Mecca itself was an ancient site of religious pilgrimage, and Muslims honor the Hebrew patriarch Abraham and consider Jesus as an important prophet in Islam. By the time of Muhammad’s death in 632, Islam was well-established in the eastern Arabian Peninsula. The religion expanded through trade and conquest and within the next hundred years, Islam became the dominant religion in North Africa, the Middle East, and Persia. By 1200, Muslim rulers also dominated South Asia and the Iberian Peninsula.

Islam brought stability to the region and commerce, learning, and the exchange of ideas flourished. The extent of Muslim influence is shown by the establishment of a center of Islamic study in Timbuktu in the middle of northern Africa, located across the Sahara Desert from Mecca in today’s Mali. The nation with the largest Muslim population in the world today, Indonesia, is a South East Asian archipelago located thousands of miles from the Arabian Peninsula. Arab traders first introduced their religion there in the 1200s. The Arab world benefited from stable administrations and strong commercial networks that allowed merchants to bring new technology, science, and mathematics from India and China into the regions they controlled, which Arab scholars refined in their own centers of learning.

Muslims, like Christians, Jews, and followers of other world religions, may share common sacred writings and liturgical traditions, but they are also divided by different theological interpretations and religious practices. In Islam, the principal division stems from an early debate over who should have led the religion after the Prophet. Sunnis, 90% of Muslims today, stem from the group who believed control should pass to the most dynamic leaders, while Shi’ites, 10% of all Muslims, followed the direct descendants of the Prophet as early principle imams (spiritual leaders) of Islam. The rulers and people of Persia—today’s Iran—embraced Shi’ism, while most of their neighbors are Sunni. Although Sunnis and Shi’ites fought one another in the early years of Islam, many have also lived together in relative peace for centuries, until the last few decades (which will be examined in later chapters).

Questions for Discussion

- How do you think the memory of the Roman Empire affected Europeans?

- How did conflict between Muslims and Christians shape European history?

The Center of World Population: Asia

In a region called the Punjab that is now divided between Pakistan and India, cities in the Indus River Valley such as Mohenjo-daro and Harappa began about 5,000 years ago, around 3000 BCE and reached their maturity by about 2600 BCE when the Egyptians were building the pyramids. Each city was home to from 30,000 to 60,000 people. The culture grew on an agricultural base focused on wheat, barley, and millet. The permanent, sedentary nature of these Indus Valley agricultural societies caused thinkers to establish more rules of conduct and to consider in more complex ways how people should live correctly in the world. A perceived need for social order led to the establishment of both religious and civil structures that are the ancestors and sources of many of the world governments and religions which still exist today. Hinduism took root beginning around 2000 BCE, based on stories of gods and goddesses described in texts called Vedas, and their relationships with one another and the world. The practices of meditation and withdrawal from worldly concerns in South Asia inspired the Buddha (who was born a prince in today’s Nepal) to engage in his own spiritual journey to enlightenment in the fifth century BCE. Buddhist ideas spread across Asia and inspired many of the spiritual aspects of Chinese, Japanese, and Southeast Asian thought.

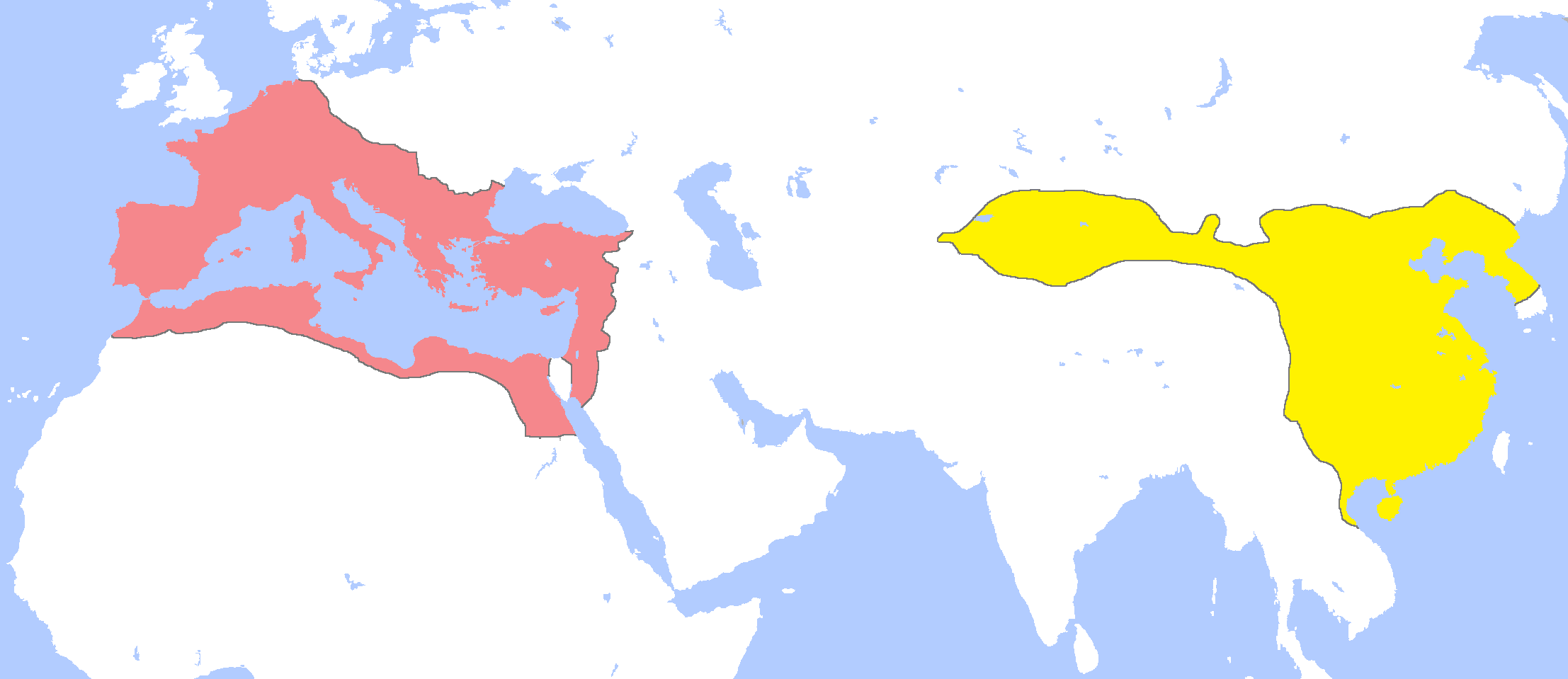

Similar to the Indus Valley culture, after thousands of years of hunting and gathering, ancient people of northern China began cultivating millet and rice. As previously mentioned, this shift to farming happened at about the same time that people of India and the Middle East began growing grains and people of the Americas grew maize, potatoes, and cassava. China’s recorded history began about 2000 BCE, or over four thousand years ago, so historians have a pretty good idea what happened there in the distant past. Based on irrigated rice agriculture, the population of China grew to 50 to 60 million people as early as 2,000 years ago. This large population was divided into several regional kingdoms whose ruling families were connected through political marriages. Beginning in 221 BCE, the most powerful family organized the kingdoms into an empire covering much of the territory of modern China. This empire lasted over two thousand years under a series of over a dozen dynasties until the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911 and the establishment of the Republic of China.

As we have seen, empires have often engaged in ambitious building projects. Some historians have suggested that big common tasks such as irrigation or defense may have been reasons and justifications for the formation of kingdoms and empires in the first place. The earliest emperors of China began immense public works programs including constructing what they called Long Walls which later formed the basis of the Great Wall, partly to protect their territory from northern tribes and partly to expand that territory northward. Around 200 BCE, the second Chinese dynasty, the Han, established a trade route called the Silk Road linking China through central Asia with Europe. Artifacts from the Roman Empire have been found in China and silk (a Chinese invention developed before 3000 BCE; the process kept secret for millennia) became a luxury fabric in Greece and Rome. The next dynasty, the Sui, dug the Grand Canal to connect the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers in the sixth century CE. This inland waterway allowed rice, wheat, and millet to be transported on a convenient and protected route instead of being transported on the ocean where shipments could be threatened by pirates. China also led the world in iron, copper, and porcelain production and created the “Four Great Inventions” of the early modern world: the magnetic compass, gunpowder, paper-making, and the printing press.

Questions for Discussion

- Is it significant that China and India have always been centers of world population?

- Why do agricultural surpluses encourage the building of cities, kingdoms, and empires?

- Is it surprising to you that the Han and Roman Empires existed at the same time and that there was trade between Asia and Europe via the Silk Road?

The Isolated Americas

The continents of North and South America are geographically separated from Europe, Asia, and Africa, which made it impossible for ancient people to migrate there in large numbers. There is some evidence that ancient mariners may have reached the Americas, but not that large numbers migrated across oceans. Most of the people who came to the Americas walked across a landmass we now call Beringia, which is exposed by falling sea levels during the ice ages that have occurred roughly every 150,000 years for the past million years or so. The land between Alaska and Siberia, currently beneath the Bering Strait, is only about 150 feet below the current sea level. During the last ice age, which began about 36,000 years ago, glaciers trapped so much water that sea levels fell over 360 feet. A region wider than Alaska was exposed, so that the Siberian steppe just continued into North America. This region, Beringia, existed for about 10,000 years and people lived there, hunting caribou, wooly mammoths, and other prey. When the ice age ended, between 11,000 and 12,000 years ago, the oceans rose to their present level and the people living in what is now Alaska entered the Americas.

The people who became the first Americans were then separated by climate change from Eurasia for over 10,000 years after the end of the ice age. As the glacier walls that had prevented them from expanding into the continent during the ice age melted, they spread quickly across both continents. During this period, which we should remember is twice as long as recorded history, the Native Americans were not idle. When they arrived in the Americas, the people found very few large animal species available to domesticate. In order to be domesticated, animals must be not only social but willing to accept humans as the leaders of their herds. Nearly all the typical farm animals of today (cattle, pigs, sheep, goats, chickens) were bred from wild species found in Africa, Asia, and Europe. Like the Europeans, Asians, and Africans, Native Americans began their own agricultural revolution after a long period of hunting and gathering; but rather than domesticating animals as other cultures did, Americans focused more on breeding wild plants over many generations, creating three of the world’s current top five staple crops.

Staple crops produce the foods that provide the greatest percentage of the calories people eat. It might surprise you that today only about fifteen staple crops account for 90% of the calories people eat every day. The top five are responsible for nearly three quarters of our food, as well as providing feed for the animals whose meat we eat. They were all discovered (actually, invented) by ancient people between six and ten thousand years ago, and three of the five were invented in the Americas. The world’s five top five staples today, in order of importance, are Maize (corn), rice, wheat, potatoes, and cassava. Only rice and wheat were known to Europe, Asia, and Africa before contact with the Americas. Natives of what is now Mexico developed maize from a native grass called Teosinte beginning about nine thousand years ago, and its use spread to nearly every part of the Americas. Over generations, women (who were the farmers in ancient Mexico) selectively bred the grass to produce more and bigger seed heads. Maize is currently the most important staple in the world for both human and animal feed, as well as in industrial uses like High Fructose Corn Syrup, plastics and fuel.

Natives of the Andes Mountains in what is now Peru and Bolivia created many varieties of Potatoes from wild tubers beginning about 10,000 years ago. Andean women developed different varieties for different growing conditions and learned to freeze dry potatoes for long-term storage. It is still possible to see varieties of potatoes in Bolivian village markets that are unknown in the rest of the world. And the people of the Amazon region not only discovered Cassava trees growing in the rainforest, but developed processes to turn the trees’ poisonous roots into manioc (what North Americans know as tapioca) between 10,000 and 7,000 years ago. Raw cassava root is toxic. So in addition to domesticating the plant, Amazonian tree farmers had to develop technologies (combinations of boiling, drying, and chemical leaching) to remove the cyanide compounds and make the manioc’s starches useful. Along with rice and wheat developed in Eurasia, maize, potatoes, and manioc are the most important staple crops in the modern world, feeding billions of people. We have ancient native Americans to thank for them.

Of course, eating nothing but maize, potatoes, and cassava would be a very bland diet. The people of central Mexico developed other plants to flavor their cuisine. The various types of hot peppers, beans, and tomatoes present in Mexican food today were enjoyed by the Olmecs and Aztecs hundreds of years before their encounter with Europeans in the sixteenth century. The Meso-Americans also ground cocoa beans and added hot water, peppers, and honey to make hot chocolate. Even today, millions of Latin Americans begin and end their day with a cup, prepared in a traditional olleta with a hand-held batidor, using chunks of chocolate. However, such a delicious drink was originally reserved for the nobility, and cocoa beans themselves were often used as a kind of currency.

Questions for Discussion

- Why would it matter that there were no large animal species in the Americas for natives to domesticate?

- Is it significant that the people breeding new staple crops in the Americas were mostly women?

We will look more closely in the next several chapters at the cultures of all these regions, as they entered the modern era. Although the people of each continent and region developed different traditions and customs, their agriculturally-based cultures shared a lot of similarities and their civilizations were all comparably advanced at the beginning of our survey.

Media Attributions

- “Native potatoes / Papas nativas” © CIP - International Potato Center is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license