Blindness and Visual Impairments

Note. Creative Commons image.

Thoughts before you read:

- What is the difference between being blind and visually impaired?

- Do you know anyone who is blind or visually impaired? How did they lose their sight?

- What would you do if you lost your sight?

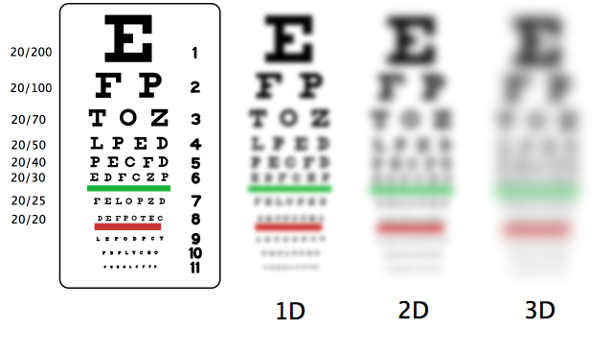

The definition of blind and/or visually impaired (BVI), provided by the International Classification of Diseases 11 (2018), is classified into two distinct groups. The two groups are distance vision impairment and near vision impairment. There are four levels of visual acuity and clarity/sharpness of vision.

Distance vision impairment:

- Mild – visual acuity worse than 6/12 to 6/18 (20/70)

- Moderate – visual acuity worse than 6/18 to 6/60 (20/70 – 20/200)

- Severe – visual acuity worse than 6/60 to 3/60 (20/200 – 20/400)

- Blindness – visual acuity worse than 3/60 (20/400 – No light perception)

Near vision impairment:

- Near visual acuity worse than N6 or M.08 at 40cm.

Visual acuity is a measurement determined by letter chart tests used when our eyes are checked; the number represents your eyes’ clarity or sharpness. For example, a person with a visual acuity measurement of 20/70 who is 20 feet away from an eye chart sees what a person with 20/20 vision can see from 70 feet away.

Note. From CVI Scotland.

An individual may have experienced vision impairment or blindness since birth or due to an injury. The result may be complete darkness, or a lack of any amount of light recognition. Other times, there may be some vision as in the examples below (Mays, 2020):

- Glaucoma: This results from an increase in fluid pressure in the eye. This reduces vision to a “tunnel” with intact vision in the center but lessening vision toward the edges. Without intervention, the tunnel reduces in size, with the possibility of total vision loss in time.

- Age-related macular degeneration: The central vision becomes increasingly unclear, although vision at the edges may stay the same. This interferes with activities such as driving, sewing and reading, which require strong near vision.

- Cataract: A cataract is a general clouding or blurring of vision which affects the entire eye lens. It may result in double vision or other challenges.

- Diabetic retinopathy: Diabetes damages the small blood vessels and arteries at the back of the eye. The damage often results in black spots or shapes that impair vision. It can result in total vision loss if left untreated.

- Nearsightedness or myopia: Here, it is possible to see nearby objects clearly, but distant objects are blurred.

- Retinitis pigmentosa: This is a genetic condition. It starts with night blindness. It may subsequently result in tunnel vision and then complete blindness.

Prevalence

According to the World Health Organization, globally, at least 2.2 billion people have a near or distance vision impairment. In at least one billion – or almost half – of these cases, vision impairment could have been prevented or has yet to be addressed. This one billion includes those with moderate or severe distance vision impairment or blindness due to unaddressed refractive error (88.4 million), cataract (94 million), age-related macular degeneration (8 million), glaucoma (7.7 million), diabetic retinopathy (3.9 million), as well as near vision impairment caused by unaddressed presbyopia (826 million)(World Health Organization, n.d.).

Distance vision impairment in low- and middle-income regions is estimated to be four times higher than in high-income regions. There are estimated to be greater than 80% near vision impairments in Western, Eastern and Central sub-Saharan Africa, while comparative rates in high-income regions of North America, Australasia, Western Europe, and Asia-Pacific are reported to be lower than 10%.

Note. Creative Commons image.

Lived Experiences

Video: Growing Up Blind (28:18)

Nine-year-old Kyren Andrew is blind and has just got a new cane. Everyone wants him to be more independent, but he is not so sure. Kyren is tempted to give up, but with the support of family and friends, he is learning that independence is not as scary as it seems.

Video: Child Grows Up Blind — The Planson Family (5:50)

Emma was born with underdeveloped eyes, though they have grown to the point where she can perceive some light and color. Emma (and her mother, Lori) is learning to read and write in Braille, but she otherwise attends classes with sighted children. She is an active five-year-old girl in gymnastics and Girl Scouts.

Video: Things you shouldn’t say or do to a visually impaired person (14:02)

This video addresses many misconceptions toward visual impairment and blindness that the author discusses.

Video: Inside an Inspiring School in India That Prepares Blind Youth for Life | National Geographic (5:23)

In West Bengal, India, a residential school for young people with visual impairments is giving its students not just hope but also joy. Some would face a bleak life if not for the care and instruction that they are receiving. Faculty and staff guide the children through a rich curriculum of classroom learning, skills training, music, and even cricket and other sports.

Video: The Family that Adopted Six Blind Children (13:30)

The Bartling family adopted six children who are all completely blind. Join them for a normal day in their life. For more information about the Bartlings, they have a website.

Video: School Helps Visually Impaired Students Reach New Horizons (3:49)

Students from across the state attend the Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired not just to earn a diploma. Here, they learn to adapt to their disability, and how to thrive independently, both in and out of school.

Diverse Learners: Individual Differences

As with other areas, consider blindness/visual impairment (BVI) as a differential ability and not a barrier to learning. Differences in ability across all human experience is part of diversity. As educators, we continue to strive to scaffold learning so that students can find their way through learning. Our teaching methods must seek to differentiate materials and provide accessibility. Examples of accessible materials can include large print books, Braille materials, photocopy enlargements, font legibility, increased contrast, pictures and worksheets, tactual books, and tactile graphics (Mays, 2020).

Consider the person’s experience with their BVI, whether it be from birth or a later loss. What is their individual history with sight? Did they have any sight? Were they able to learn about colors? Is their experience solely with touch? Did they learn shapes through tactile experience? They may have developed ways to address some of the challenges of society and apply some of those skills to future learning. Educators can focus on these strengths and assets as they consider instructional materials and accessibility.

The capacity to learn is evident, as in the results from a research study by Rindermann et al. (2020). Results from the WISC-IV, a psychological assessment, showed a higher working-memory capacity in children with BVI than sighted children. Working memory involves the ability to compare and store different information in short-term memory. Working memory capacity is highly correlated with intelligence. This evidence is shared to ensure that you, as a future educator, do not underestimate your students’ abilities or provide them with learning opportunities that lack the challenge for growth.

What is Braille?

Video: Braille: What is it like to read without sight? (6:22)

The American Foundation for the Blind (2015) states that Braille is a “system of raised dots that can be read with the fingers through touch by people who are blind or who have low vision and with eyes by people who are sighted.” Braille is not a language; rather, it is a code in which many other languages such as English, Chinese, Spanish and African languages can be written so that visually impaired people can access them via tactile decoding. It fundamentally provides a means of literacy and communication to all people who are blind or have low vision.

Braille defines literacy for the visually impaired, and it has been accepted globally as the means of written communication for people who are blind. Thus, anyone who can read and write Braille is deemed literate, whereas a visually impaired person who cannot read or write Braille is considered illiterate by the community of people who are sighted, even if a person can use assistive devices properly. Braille gives blind learners a sense of privacy, confidentiality and independence because they will be able to label their own belongings and read and write on their own without outside help. Moreover, Braille upholds the rights of the blind. Being able to read and write in Braille supports the right of the visually impaired to information; for example, they will have knowledge about current affairs because they can access printed texts that have been converted into Braille code. A learner who is visually impaired must learn to read and write Braille manually before learning to use assistive technology or devices such as the Mountbatten Brailler.

Another form of Braille is Unified English Braille (UEB). This Braille code was developed to combine several existing Braille codes (namely, a literary code, a science code, a mathematics code and a computer code) into one common code so that it can be used by all English-speaking countries throughout the world. Unified English Braille (UEB) took over 20 years to develop. It has been adopted in all the major English-speaking countries worldwide, including Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Nigeria, South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States (Kao & Mzimela, 2019).

Expanding the School Curriculum for Blind and Visually Impaired Students

The curriculum for blind and visually impaired (BVI) students must be comprehensive, covering essential areas to ensure a holistic and inclusive educational journey. Special education for BVI learners is a low-incidence field, leading to a notable gap in the provisions offered by ordinary public institutions. These schools often fall short in providing access to suitable technology, adapting teaching methods, offering learner support, and demonstrating flexibility in curriculum modifications (Mays, 2020). As educators, it is crucial to devise strategies that not only make learning materials accessible to all students but also promote the acquisition of knowledge and skills vital for independence and life beyond the classroom.

To effectively support and inspire BVI students, the initial step involves cultivating meaningful relationships. Understanding your student’s strengths and challenges allows for the establishment of trust, which is instrumental in creating a motivating and enriching learning environment. This relationship is the foundation for introducing new materials in a way that is both inspiring and educational.Moreover, it is the educator’s responsibility to continuously explore and integrate necessary resources, preparing the classroom and school setting to meet the diverse needs of learners.

Nine Essential Strategies

According to the Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired, there are nine critical areas where the school curriculum can be significantly enhanced to benefit BVI students (Mays, 2020). By focusing on these areas, educators can develop a more accessible, engaging, and effective curriculum tailored to the unique needs of BVI learners.

1. Compensatory or Functional Skills

Compensatory or functional skills are foundational to literacy, communication, and the delivery of specialized instruction. It’s essential to equip learners with study skills tailored to their needs and to provide information in accessible formats. This includes the use of Braille, large print, tactile symbols, and audio materials to facilitate effective learning.

2. Sensory Efficiency

Sensory efficiency skills are crucial for students to compensate for visual impairment. Scaffolded support in developing listening, speaking, and touch skills can be crucial across the curriculum. Instructors play a pivotal role in helping learners optimize the use of their residual sight and individual coping skills.

3. Orientation and Mobility Support

From an early age, students require training to navigate various environments safely and efficiently. This involves teaching them to move independently and securely, whether by using a cane or the assistance of a guide dog.

4. Social Interaction Skills

Nonverbal cues, predominantly visual, play a significant role in social interactions. Blind and visually impaired learners often need assistance in interpreting auditory signals to understand how others feel, fostering better integration and preventing social isolation.

5. Assistive Technology

Real-time access to information through technology is non-negotiable for these learners. The curriculum should include teaching students how to utilize screen readers, Braille devices, and other tools for reading, writing, and note-taking.

6. Independent Living Skills

Blind and visually impaired learners may not learn life skills by observation and thus require structured support. Educators should help students develop abilities in personal hygiene, food preparation, financial management, and household chores.

7. Recreation and Leisure Skills

Structured engagement and modifications are necessary for the development of recreation and leisure skills. This is to ensure that these learners have the same opportunities to dance, sing, and participate in sports as their sighted peers.

8. Career Education

Direct observation isn’t a viable option for blind and visually impaired learners to learn about different careers. Hence, the curriculum should provide tactile experiences of workplaces and opportunities to interact with professionals.

9. Self-Determination

Finally, fostering self-determination is about empowering students to make their own decisions, advocate for themselves, and take personal responsibility. This helps in avoiding the pitfall of “learned helplessness” and encourages learners to recognize the valuable contributions they can make to society.

The curriculum for blind and visually impaired students should be expansive, addressing these key areas to foster a holistic and inclusive educational experience.

Universal Design for Learning

One teaching method you may choose to use that complements the nine essential strategies is Universal Design for Learning (UDL). This method is an educational framework that aims to optimize teaching and learning for all people based on scientific insights into how humans learn. Originating from the concept of “curb cuts” – the small ramps built into sidewalk edges to accommodate wheelchairs, which also ended up benefiting a wider range of users like cyclists and parents with strollers – UDL has expanded to instructional design with a focus on providing equitable access to learning opportunities. It emphasizes the need for flexible learning environments that can accommodate individual learning differences. By incorporating multiple means of representation, expression, and engagement, UDL seeks to remove barriers to learning, thus enabling all students, including those with disabilities, to achieve academic success. This approach not only promotes inclusivity but also encourages innovation in teaching strategies, thereby enhancing the educational experience for students at community colleges and beyond (CAST, 2024).

Video: Teaching Methods: Universal Design of Learning (UDL) (8:04)

Video: NWABA (Northwest Association for Blind Athletes) Organizational Overview (3:21). It features staff members discussing and instructing on the fundamental aspects of the Universal Design for Learning, specifically tailored for working with individuals who are blind and visually impaired. This content aims to provide insights into accessible learning strategies and practices that enhance the educational experiences of visually impaired students, aligning with principles of inclusivity and adaptability in educational environments.

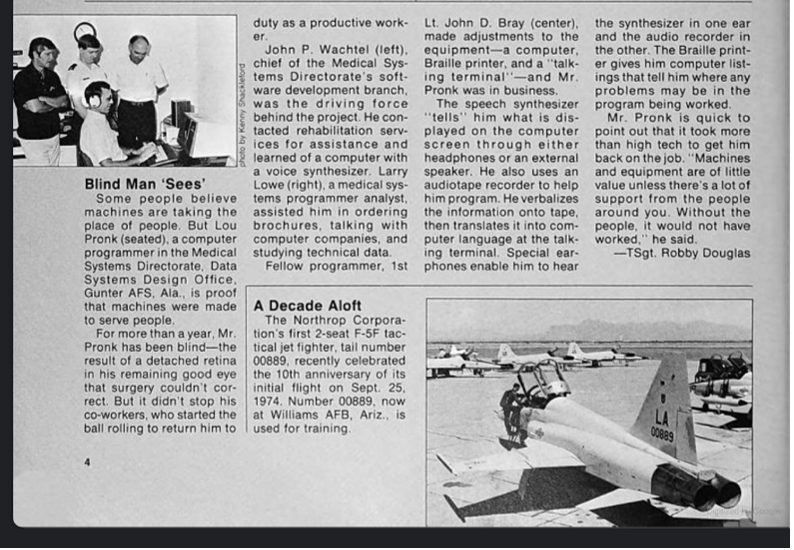

Meet “Uncle Lou”

A family story by one of the textbook authors, LeAnne Syring: Lou Pronk was blind after two separate accidents as an adult. He worked for the United States Department of Defense as a computer programmer in the Data System Design Office of the Directorate of Medical Systems. His job was to keep track of all supplies. For example, he said if there was some kind of disaster and the site needed 400 cots, he had to find them and get them sent. He used a computer program, which appeared odd, since he had no need for a monitor, which is part of a typical computer programming setup. There is one in the photo below, but they eventually removed it, as it was not needed. Lou shared an incident where he was on vacation, and the person filling in for him (a sighted person) could not figure out where to find the information in the manual and find what was needed. Lou told him the exact location of the information: page, column, paragraph, sentence. After retirement and the death of his beloved wife, he lived alone and took care of himself. He cooked, cleaned, built a deck on his house, and did anything else that needed to be done. When he did his laundry, he would press his white t-shirts and his khaki pants. He loved a crease down the center of his leg. He was awarded the Handicapped Employee of the Year from his division in the Department of Defense. He was a proud veteran and family man. He was amazing. He passed away in 2011 leaving a legacy of love, determination, and a never-give-up attitude.

Note. Airman (January 1985) featuring Lou Pronk.

Here are some teaching tips shared by “Uncle Lou”:

- Blind people do not go around feeling the walls to see if there is Braille on it, so skip the signs unless you indicate where they are. Stop trying to make yourself feel better.

- Keep furniture in the same place and allow adequate walking space

- Do not open car doors; let the blind person open it themself so they know where it is. An open car door is dangerous.

- No need to raise your voice; blindness affects the eyes, not necessarily the ears.

- Do not limit people; let them try things they want to try (Lou was a carpenter in retirement and built a deck on his house, and one on a neighbor’s house without any modified tools).

- Play music in the background of the room; it helps blind people navigate their surroundings through an echo location-type assistant.

Think, Write, Share

- What are three accommodations you would make to the classroom environment if you were to have a blind/visually impaired student?

- Does every blind child know Braille? How do they learn it?

- Do all blind people need to know Braille? Why or why not?

References

de Verdier, K., Ulla, E., Löfgren, S., & Fernell, E. (2018). Children with blindness – major causes, developmental outcomes and implications for habilitation and educational support: A two-decade, Swedish population-based study. Acta Ophtalmologica, 17553768, 3. Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/aos.13631

Kao, M.A. & Mzimela, P.J. (2019). ‘“They are visually impaired, not blind … teach them!”:

Grade R in-service teachers’ knowledge of teaching pre-reading skills to visually impaired learners’, South African Journal of Childhood Education 9(1), a651. https://doi.org/ 10.4102/sajce.v9i1.651

Mays, T. (2020). Visual impairment as a disability and/or diversity. In R. Ferreira & M.M.

Sefotho (ds.), Understanding education for the visually impaired (Opening Eyes Volume 1), pp. 3–19, AOSIS, Cape Town. https://doi.org/10.4102/aosis.2020.BK179.01

Rindermann, H., Ackermann, A. L., & te Nijenhuis, J. (2020) Does blindness boost working memory? A natural experiment and cross-cultural study. Frontiers in Psychology 11,1571. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01571

World Health Organization. (2022, October 13). Blindness and vision impairment. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/blindness-and-visual-impairment