Articulation

Definition

An “articulation disorder” means the absence of or incorrect production of speech sounds or phonological processes that are developmentally appropriate. For the purposes of this section, the phonological process means a regularly occurring simplification or deviation in an individual’s speech as compared to the adult standard, usually one that simplifies the adult phonological pattern. Articulation patterns that are attributed only to dialectical, cultural, or ethnic differences or to the influence of a foreign language must not be identified as a disorder.

MN Eligibility Criteria

The following criteria are taken from the Minnesota Department of Education and Legislature (Minnesota Revisor, 2007).

- A pupil has an articulation disorder and is eligible for speech or language special education when the pupil meets the criteria in subitem (1) and either subitem (2) or (3):

(1) the pattern interferes with communication as determined by an educational speech language pathologist and either another adult or the pupil; and

(2) test performance falls 2.0 standard deviations below the mean on a technically adequate, norm-referenced articulation test; or

(3) a pupil is nine years of age or older and a sound is consistently in error as documented by two three-minute conversational speech samples.

Characteristics (ASHA)

Speech sound disorders refer to any difficulty or combination of difficulties with perception, motor production, or phonological representation of speech sounds and speech segments—including phonological rules that explain allowable speech sound sequences in a language.

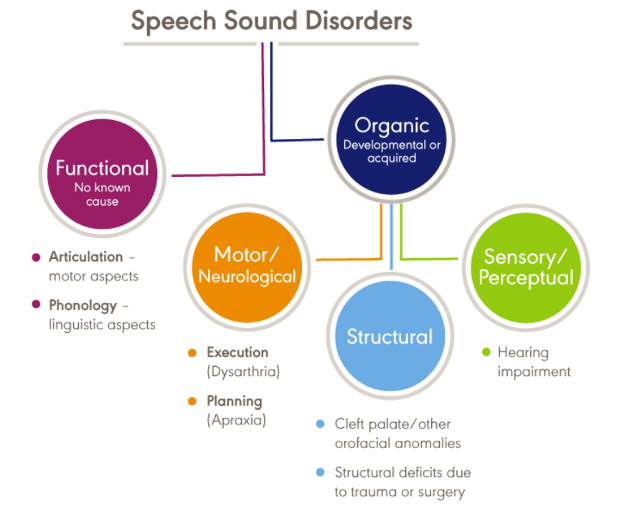

The cause of speech sound disorders can be either organic or functional in nature. Organic speech sound disorders stem from an underlying motor/neurological (e.g., childhood apraxia of speech), structural (e.g., cleft palate), or sensory/perceptual cause (e.g.. deafness). Functional speech sound disorders have no known cause. See the figure below taken from the ASHA website:

Note. From ASHA.

Note. From ASHA.

Functional speech sound disorders include those related to the motor production of speech sounds (articulation disorders) and those related to the linguistic aspects of speech production (phonological disorders). It is often difficult to clearly distinguish between articulation and phonological disorders; therefore, many professionals prefer to use the broader term, “speech sound disorder,” when referring to speech errors with an unknown cause.

Articulation Disorders

Articulation disorders focus on errors (e.g., distortions and substitutions) in the production of individual speech sounds. The most common sound misarticulations are omissions, distortions and substitutions.

Omissions: Omission of a phoneme occurs when a child does not produce a sound in a word. An example of an omission would be a child who says “ba” for “ball.”

Substitutions: A very common speech sound error is a substitution. Common substitutions are: /b/ for /v/, e.g., “hab” for “have,” /b/ for /f/, e.g., “bive” for “five,” /d/ for /th/, e.g., “da” for “the,” /f/ for /th/, e.g., “baf” for “bath,” /w/ for /l/, e.g., “wittle” for “little,” and /w/ for /r/, e.g., “wat” for “rat.” However, some children exhibit substitutions that are less common (e.g., /f/ for /s/, e.g., “fun” for “sun.”).

Distortions: Distortions occur when a child uses a non-typical sound for a typically developing sound. One of the more common and difficult sound substitutions to treat is the lateral /s/, where the air escapes out of the sides of the mouth during /s/, /sh/ or /ch/ production, and not over the center of the tongue. This results in an excessively noisy or slushy quality to these sounds (Speechlanguage-Resources.com, n.d.).

The following chart is taken from the website Speech Sisters.

Note. From Speech Sisters.

Phonological Disorders

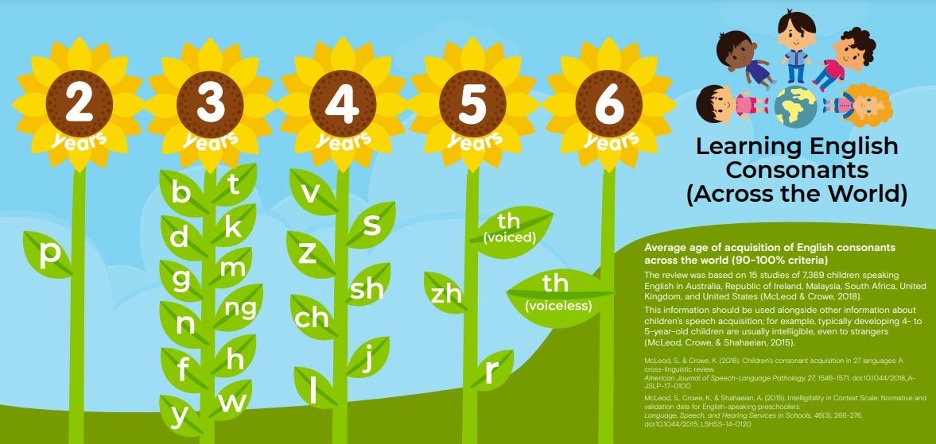

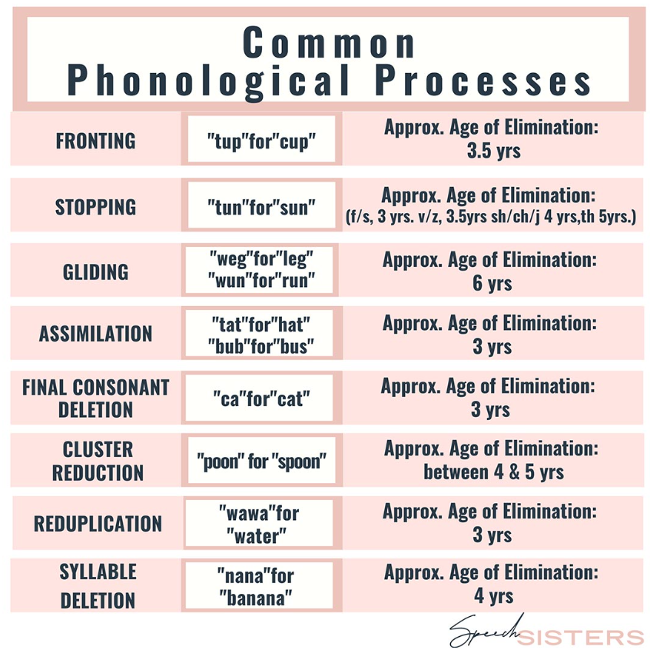

Phonological disorders focus on predictable, rule-based errors (e.g., fronting, stopping, and final consonant deletion) that affect more than one sound. Typically, developing children use phonological processes to simplify speech as they are learning to talk because they often do not have the ability to coordinate their lips, tongue, teeth, palate, and/or jaw for clear speech articulation. For example, students may reduce consonant clusters to a single consonant such as “nake” for “snake” or delete the final syllable in a word, saying, “ca” for “cat.” Below is a chart including some of the most common phonological processes, examples of each, and the age at which they should be eliminated.

What’s a Phonological Process?(Sound Speech and Hearing Clinic)

The following chart is taken from the website Speech Sisters.

Note. From Speech Sisters.

Note. From Speech Sisters.

Apraxia

The following information has been taken directly from Nemours KidsHealth.

Childhood apraxia of speech, sometimes called verbal dyspraxia, is a speech disorder in which the brain has difficulty in motor planning and getting the tongue, lips, and jaw to move correctly for talking. Children with the disorder know what they want to say but cannot coordinate the muscle movements needed to make the sounds, syllables, and words. Apraxia symptoms can vary widely. Children with apraxia may also have:

- other language delays.

- sensitivity problems with their mouths such as not liking to brush their teeth or eat crunchy foods.

- problems with motor skills and coordination.

- problems learning to read, write, and spell.

Students with apraxia may:

- need assistive devices or alternative communication methods to help them in class.

- need seating close to the front of the class.

- feel anxious, nervous, or frustrated when it comes to speaking in class.

- be at risk for bullying.

- need accommodations for missed class time and assignments due to frequent speech therapy, physical therapy, and occupational therapy sessions.

- benefit from having an individualized education plan (IEP) or 504 education plan.

Apraxia can affect many aspects of a student’s education and academic performance. It is important for teachers to work with speech-language pathologists and families to help ensure that students get the proper support. Keep your students with apraxia involved in the classroom. Keep in mind that some may also have coordination problems. Give students extra time to do assignments and plenty of time to communicate their needs. Because students with apraxia are at risk for bullying, just like many other students with special needs, try to create opportunities for collaboration and friendships with classmates.

Intelligibility

These data have been taken from Speech Sisters.

Between the ages 19–24 months, children should be 25–50% intelligible to an unfamiliar listener.

- Between 2–3 years old, they should be 50–75% intelligible to an unfamiliar listener.

- Between 4–5 years old, they should be 75–90% intelligible to an unfamiliar listener, even if a few articulation errors are still present in their speech.

- By kindergarten, a child should be 100% intelligible to an unfamiliar listener.

Causes/Etiology

The cause of functional speech sound disorders is not known; however, there are some common risk factors that have been reported, including the following (taken directly from ASHA):

- Gender—The incidence of speech sound disorders is higher in males than in females (e.g., Everhart, 1960; Morley, 1952; Shriberg et al., 1999).

- Pre- and perinatal problems—Factors such as maternal stress or infections during pregnancy, complications during delivery, preterm delivery, and low birthweight have been found to be associated with delays in speech sound acquisition and with speech sound disorders (e.g., Byers Brown, Bendersky, & Chapman, 1986; Fox, Dodd, & Howard, 2002).

- Family history—Children who have family members (parents or siblings) with speech and/or language difficulties are more likely to have a speech disorder (e.g., Campbell et al., 2003; Felsenfeld, McGue, & Broen, 1995; Fox et al., 2002; Shriberg & Kwiatkowski, 1994).

- Persistent otitis media with effusion—Persistent otitis media with effusion (often associated with hearing loss) has been associated with impaired speech development (Fox et al., 2002; Silva, Chalmers, & Stewart, 1986; Teele, Klein, Chase, Menyuk, & Rosner, 1990).

English Language Learners

Assessment

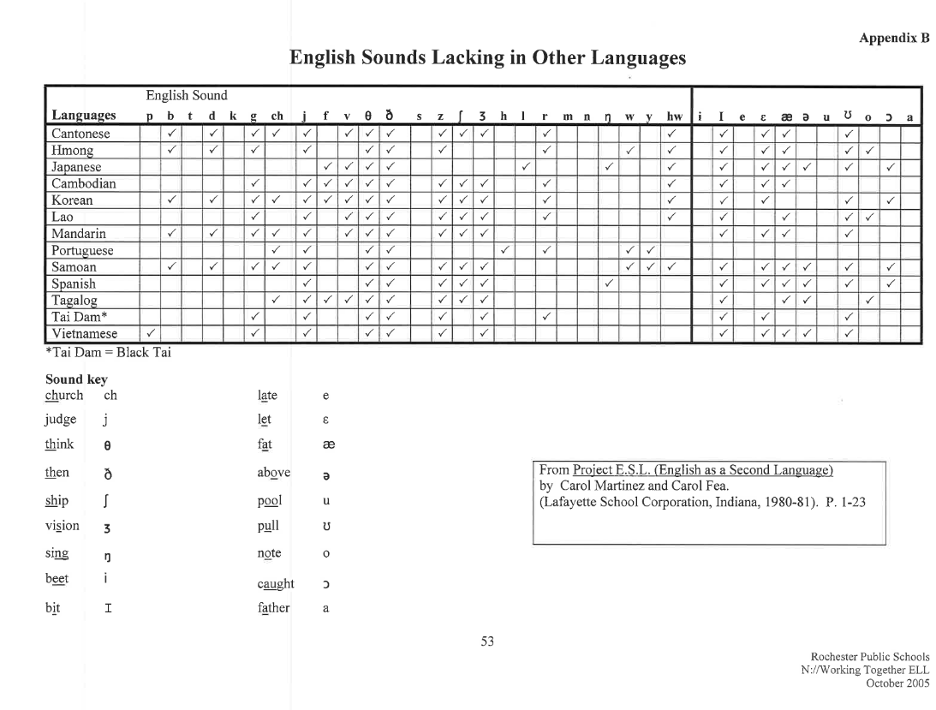

Assessment of a bilingual student requires an understanding of both or all of the student’s linguistic systems because the sound system of one language can influence the sound system of another language. The assessment process must identify whether the differences are truly related to a speech sound disorder (occurring in both languages or dialects) or are normal variations of speech caused by the first language.

When assessing a bilingual or multilingual individual, clinicians typically:

- complete a linguistically and culturally diverse interview with a parent or guardian to understand the student’s language history and use and determine which language(s) should be assessed.

- Determine the phonemic inventory (ASHA phonemic inventories), phonological structure, and syllable structure of the student’s non-English language(s), and/or dialect.

- Assess articulation/phonological skills in both languages in single words as well as in connected speech while accounting for dialectal differences. This is typically done through non-standardized measures, commonly with an interpreter if needed. However, there are some standardized tests which are normed on multilingual speakers that can be used (e.g., Goldman Fristoe Test of Articulation-3) while determining any cross-linguistic effects (the student’s native language influences the production of sounds in English, resulting in an accent (Fabiano-Smith & Goldstein, 2010). Any dialectal differences would not be scored as an error on the test and would not be included in the standardized score.

See phonemic inventories and cultural and linguistic information across languages and ASHA’s Practice Portal page on Bilingual Service Delivery. See the Resources section for information related to assessing intelligibility and life participation in monolingual children who speak English and in monolingual children who speak languages other than English.

Influence of Accent (ASHA)

“An accent is the unique way that speech is pronounced by a group of people speaking the same language and is a natural part of spoken language. Accents may be regional; for example, someone from New York may sound different than someone from South Carolina. Foreign accents occur when a set of phonetic traits of one language are carried over when a person learns a new language. The first language acquired by a bilingual or multilingual individual can influence the pronunciation of speech sounds and the acquisition of phonotactic rules in subsequently acquired languages. No accent is “better” than another. Accents, like dialects, are not speech or language disorders but, rather, only reflect differences.” See ASHA’s Practice Portal pages on Bilingual Service Delivery and Cultural Responsiveness.

Influence of Dialect (ASHA)

Not all sound substitutions and omissions are speech errors. Instead, they may be related to a feature of a speaker’s dialect (a rule-governed language system that reflects the regional and social background of its speakers). An example of a dialectal variation in phonology occurs with speakers of African American English (AAE) when a “d” sound is used for a “th” sound (e.g., “dis” for “this”). This variation is not evidence of a speech sound disorder but rather one of the phonological features of AAE.

Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) must be able to distinguish between dialectal differences and communicative disorders. They must recognize that all dialects are rule-governed linguistic systems and understand the rules and linguistic features of dialects that are represented by their student population. They must also be familiar with nondiscriminatory testing and dynamic assessment procedures such as identifying potential sources of test bias, administering and scoring standardized tests using alternative methods, and analyzing test results considering existing information regarding dialect use (see, e.g., McLeod, Verdon, & The International Expert Panel on Multilingual Children’s Speech, 2017).

See ASHA’s Practice Portal pages on Bilingual Service Delivery and Cultural Responsiveness.

The following chart was taken from: Project ESL by Carol Martinez and Carol Fea, Layfayette School Corporation, 1980–81, pp. 1–23.

Note. From Project ESL.

Note. From Project ESL.

Team Interventions and Support

Ways to support your student outside the speech room. This could be provided by any adult who works with the student.

- Using a gestural cue to indicate a targeted speech sound

- Providing a verbal model of the accurate production

- Providing wait time to allow the student to attempt challenging speech sounds