Deaf-Blindness

Note. Creative Commons image.

Note. Creative Commons image.

“If the child is profoundly deaf and totally blind, their experience of the world extends only as far as the fingertips can reach” (Miles, 2008).

Deaf-blindness indicates a dual sensory loss of sight and hearing. This loss does not necessarily mean that the person is totally deaf and totally blind but is varied in some degree from moderate to severe loss (Grisham-Brown et al., 2018). Learners who are deaf-blind make up less than 1% of the school-age population, 90% of which have additional physical, medical, or cognitive disabilities (National Center on Deaf-Blindness, 2023). However, the preparation you make to become aware of their learning needs will help you in other disability areas. Every time we open our thinking to engage in new ways of teaching and understanding, we become better teachers.

There are three distinct groups in the deaf-blind population:

- People with congenital/pre-lingual deaf-blindness

- People with acquired/post-lingual deaf-blindness – those who acquire both types of impairment during their lives, or those with single sensory impairment (vision or hearing) by birth and then subsequent impairment of another sense (vision or hearing)

- Dual sensory loss/impairment of vision and hearing due to age-related changes in older adults, each of which can vary in severity as well as order and time since onset (Jaiswal et al., 2018)

The most famously known person who was deaf-blind was Helen Keller (1880–1968). Helen Keller became deaf and blind from a childhood illness prior to her second birthday (Michels, 2015). Helen Keller was taught by Anne Sullivan, using both finger spelling and by touching Anne’s mouth as Anne spoke. Helen also learned Braille. She became a writer and was an activist for socialism. She wrote two books. Her life story, Miracle Worker, won an Academy Award in 1955.

Video: Deaf-Blind Awareness — NFADB (4:30)

Video: Meeting a Deaf-blind Person (2020) 4:08

Simple communication, such as greeting a deaf-blind person, may be a complex thought process. This video gives you a few tips to help understand the various ways to greet deaf-blind people. It is dependent on whether they have some sight, some hearing, use sign language, use pro-tactile communication, or have cochlear implants. Each person is unique, and it is up to you to bridge the communication.

An additional challenge for the deaf-blind person is mobility. They lack access to information on available public transportation and how to navigate their environment (Jaiswal et al., 2018). Understanding simple guidance techniques can help you instruct and interact with a deaf-blind person. The video below gives guidance techniques.

Video: NEMP — Deaf-blind Awareness Training: How to Guide a Deafblind Person during an Emergency (3:49)

As noted previously, finding a communication strategy that works for the deafblind person is essential. The following video shows various strategies you may need to try.

Video: Deaf-blind Communication (7:11)

Various communication strategies for deaf-blind people are shared.

Tactile sign language is the primary conversational language in the deaf-blind community. American Sign Language (ASL) is based on a fingerspelled alphabet for proper nouns and a combination of facial and hand gestures for grammar and vocabulary. Tactile sign language involves the use of ASL by the “speaker” while the “listener” places their hand over the “speaker’s” hand, tracking the letters and gestures as they “speak” (Johnson et al., 2021). This preferred communication is limited by the fact that not everyone knows ASL, necessitating reliance on an interpreter.

Video: New Touch-based Language by Deaf-blind People: Protactile (5:10)

A new language has been spreading within the Deaf-blind community and has revolutionized how some deaf-blind people communicate. Called Protactile, or PT, the language uses touch as its medium of communication. PT emerged in 2007, when a group of deaf-blind people in Seattle began exploring their natural tactile instinct. Rooted in deaf-blind people’s experience, PT aims to resolve previous communication difficulties for deaf-blind people and advance the community’s autonomy. Today, the language has reached thousands of people and is still evolving.

An interesting advancement on protactile communication is being developed by a group of people led by Samantha Johnson. She took an ASL course in college and was assigned to go out and speak to someone using ASL. She noticed the need for an interpreter and asked the deaf-blind person what would happen if no interpreter were available. The answer was troubling. Samantha began the development of TATUM (Tactile ASL Translational Use Machine). View the video below to learn more.

Video: Meet TATUM, a Tactile Sign Language Robot (4:22)

Groundbreaking research is being conducted on a robotic hand that can provide the tactile ASL needed by the deaf-blind person but is programmed by a person who does not know ASL, thus eliminating the need for an interpreter.

Note. (a) Overview of the haptic cap. (b) The micro-controller and batteries in a 3D-printed mount attached on top of the visor. (C) The exposed coin motors attached in an array to the elastic front panel of the cap.

Another technological advancement is in response to the issue of mobility. Researchers are working on a scene-monitoring device that would detect moving subjects and relay the information back to the deaf-blind person wearing the device on a hat. This would enable the deaf-blind person to navigate their environment more easily.

Supports for Learning

You may be wondering, how will I teach someone who is deaf-blind? People who are deaf-blind are isolated, and especially vulnerable, due to a lack of access to their environment. It is essential that you work with them to connect them to their surroundings and the people in it. Research continues to show a lack of preparedness on the part of educators, mainly due to the low incidence of deaf-blind children. Teachers find themselves teaching, caring for, and supporting these students without being prepared and having to seek information at the same time (Mangu & Masuku, 2020).

The most difficult interaction is communication; yet, it is the most important (Mangu & Masuku, 2020). Frustration with communication comes from the student trying to communicate their needs and the teacher trying to interpret the communication. In many cases, these trials end up in a lack of communication and connection. Training on communication strategies is essential. Mangu and Masuku (2020) recommend a collaborative team of educators, therapists, and families to support both the educator and the student who is deaf-blind.

The lack of ability to communicate often results in frustration, causing unwanted behaviors. Researchers recommend designing activities that provide meaningful reinforcement of the behavior and the desired support skills (Singer et al., 2021). Self-selected repetitive behaviors that may distract from learning or be harmful need to be replaced with desirable behaviors. Reinforcers must have high interest and preference for the deaf-blind student. Using technology-based communication devices may be more practical and convenient to promote adaptive responses and reduce problem behaviors (Singer et al., 2021).

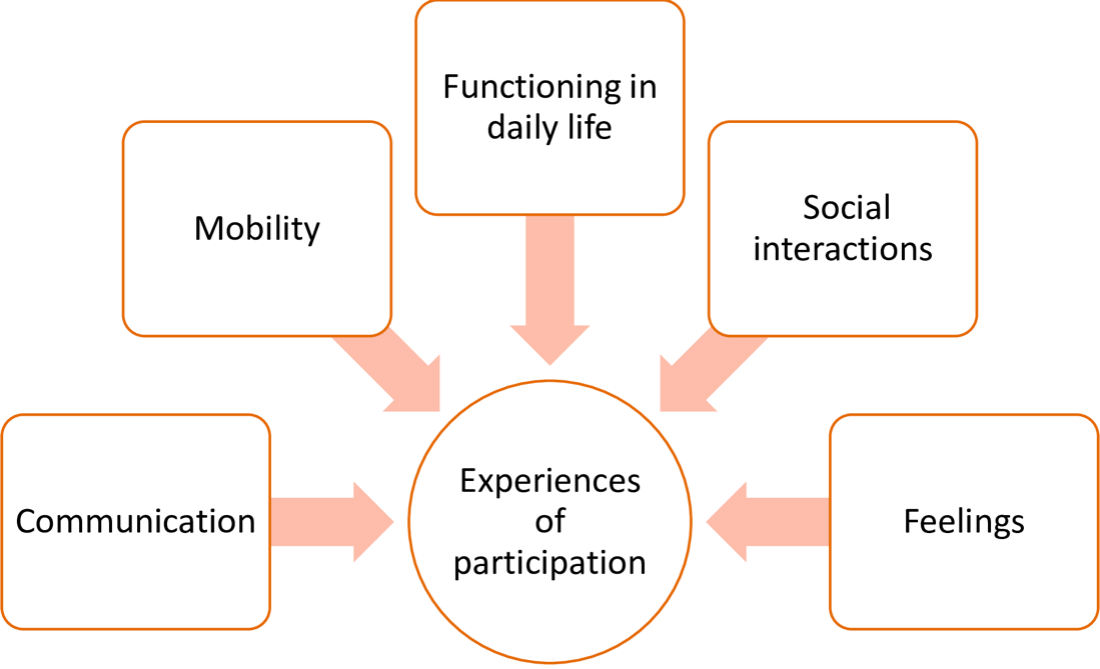

Note.From Jaiswal et al. (2018).

Amy Query is a teacher of students with deaf-blindness. She shares how exciting it is to see these children gain access to their world and build their communication skills. She works hard for her students every single day, and we celebrate her success in the following hashtags: #TeacherFeature #WeAreUSDB #deafblind #utahblindschool

Video: Teaching Children Who Are Deaf-blind (6:11)

Also noted are the challenges that occur during daily living: reading, cooking, dressing, walking in the community, shopping, attending social events, going to the doctor, and using a telephone and/or answering machine (Jaiswal et al., 2018). Helping the deaf-blind student navigate these challenges is up to you and the team of support professionals and parents.

Beyond High School

Beyond high school, most people who are deaf-blind do not seek further education, have lower rates of employment, and struggle with independent living (Barnhill, 2021). Research has found some indicators that contribute to better outcomes.

- Paid work experience in high school

- Parental expectations of employment

- Receipt of vocational rehabilitation services

- Educated in inclusive settings

(Barnhill, 2021)

The Utah Deaf-blind Project has developed a three-part plan to improve transitional outcomes for students who are deaf-blind (as cited in Barnhill, 2021).

- Increase collaboration: Promote collaboration at the school and state levels. Also promote knowledge of systems and services available to connect students to adult agencies and the services they provide.

- Increase understanding of the student: A team of professionals, parents, and agency representatives should work together to support the student’s needs for their transition to adult life. Their adult life should include the student’s interests, strengths, and needs.

- Increase students’ access: Access needs include appropriate assessments, transition courses, and opportunities for internships and paid employment. Creative thinking needs should also be involved for the student to be successful.

These students require specific interventions due to their limited access to visual and auditory information in their environment. Strategies developed for hearing loss or specifically for vision loss will not meet their needs. Students who are deaf-blind will need assistance with behavioral and educational needs. Evidence-based practices and strategies modified to meet the students’ sensory support needs may include using tactile cues, closer presentation of materials, preferred seating, print enlargement, repetition of verbal directions, and additional time to respond (Grisham-Brown et al., 2018).

Lived Experiences

Real stories of people who are deaf-blind are perhaps the best way to understand who they are, what they need, and how you can help. Below are a few stories that are both inspirational and informative.

Video: How I Cope And Enjoy Life As a Deaf & Blind Person | Being Me | Only Human (28.29)

Heather Lawson was born deaf, and as she grew up, she started losing her sight. She could cope as a blind person but was not sure how she could cope with being deaf and blind. This is her story and how she not only copes with her disabilities but how she makes the most of life. Only Human celebrates and explores the unique and personal qualities we all have. Our channel offers a range of TV series and documentaries about human experiences and life journeys – while looking at the challenges that life throws at us, turning ordinary people into everyday heroes.

Video: A Blind and Deaf Teen Who’s Defying the Odds (6:07)

Marvin is an incredible young man and varsity football player who has not let anything stand in the way of doing what he loves.

Video: My Child is Deaf and Blind: NDCS Family Story (5:05)

Parents Kevin and Jane tell us about life with their deaf-blind son Gethin, including why they have taken up rock climbing!

Video: How Haben Girma Became Harvard Law School’s First Deafblind Grad (6:39)

Haben Girma was born without hearing or vision but refuses to be hindered by her ability status—she dances, practices comedy, surfs, skis, and frequently travels the world. In 2013, she became the first and only deaf-blind student to graduate from Harvard Law and went on to become an attorney. After conceptualizing her own method of communication, Haben also began advocating for equal accessibility in tech developments. Though it is common for people to marvel at her accomplishments, she is adamant about not being called “inspirational” but rather to let that feeling drive action and change.

Video: Becca Meyers: Deaf-blind Paralympic Swimmer Spreading Optimism (3:51)

26-year-old Becca is a two-time Paralympic swimmer for Team USA, diagnosed with Usher syndrome type 1 (USH1) at only four years old. However, she has never let her diagnosis with Usher syndrome stop her from doing exactly what she puts her mind to.

Deeper Dive

Family and Student Resources (provided by Barnhill, 2021):

- The National Family Association for Deaf-blind is a national nonprofit family organization that seeks to connect, educate, and empower families of individuals who are deaf-blind.

- The National Center on Deaf-blindness provides information for individuals with deaf-blindness and the people who work with them. It also has a large library of resources related to transition for individuals who are deaf-blind.

- The Helen Keller National Center for Deaf-blind Youth and Adults offers training in assistive technology, vocational services, orientation and mobility, communication, and independent living in New York or the individual’s own community through KDNC regional representatives.

- Parent Training and Information Centers are state centers that provide information to parents to help their children, youth, and young adults with all disabilities live included, productive lives as members of the community.

- State offices of vocational rehabilitation are state agencies that support individuals with disabilities in obtaining employment through partnerships with employers, school districts, higher education, and other agencies.

- State deaf-blind projects exist in every U.S. state. They provide training, information, resources, and technical assistance to families, educational teams, and the community on educational practices for infants, children, and youth who are deaf-blind.

References

Barnhill. (2021). Raising expectations and improving transition outcomes for students who are deafblind. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 115(6), 585–589. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145482X211061201

Grisham-Brown, J., Değirmenci, H. D., Snyder, D., & Luiselli, T. E. (2018). Improving practices for learners with deaf-blindness: A consultation and coaching model. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 50(5), 263–271. doi: 10.1177/0040059918763123

Jaiswal, Aldersey, H., Wittich, W., Mirza, M., & Finlayson, M. (2018). Participation experiences of people with deafblindness or dual sensory loss: A scoping review of global deafblind literature. PloS One, 13(9), e0203772–e0203772. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203772

Johnson, S., Gao, G., Johnson, T., Liarokapis , M., & Bellini, C. (2021). An adaptive, affordable, open-source robotic hand for deaf and deaf-blind communication using tactile American Sign Language. 2021 43rd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Mexico, (pp. 4732–4737). doi: 10.1109/EMBC46164.2021.9629994

Kassem, Caramazza, P., Mitchell, K. J., Miller, M., Emadi, A., & Faccio, D. (2022). Real-time scene monitoring for deaf-blind people. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), 22(19), 7136–. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22197136

Manga, & Masuku, K. P. (2020). Challenges of teaching the deaf-blind learner in an education setting in Johannesburg: Experiences of educators and assistant educators. South African Journal of Communication Disorders, 67(1), e1–e7. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajcd.v67i1.649

Michels, D .(2015). Helen Keller. National Womens History Museum. Retrieved August 9, 2023, from www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/helen-keller

Miles, B. (2008). Overview of deaf-blindness. The National Information Clearinghouse On Children Who Are Deaf-Blind. https://www.nationaldb.org/info-center/overview-factsheet/

National Center on Deaf-blindness (2023) https://www.nationaldb.org/

Singer, Ivy, S. E., & Myers, S. (2021). Reducing stereotypes for a student with deafblindness.

Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 115(4), 286–298. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145482X211027502

Vasanth K, Macharla, M., & Varatharajan R. (2019). A self-assistive device for deaf & blind people using IOT: Kathu-Kann Thaan Thunai Eyanthiram. Journal of Medical Systems, 43(4), 88–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-019-1201-0

Warnicke, Wahlqvist, M., Anderzén-Carlsson, A., & Sundqvist, A.-S. (2022). Interventions for adults with deafblindness – An integrative review. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), 1594–1594. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08958-4