13 Disability Categories

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) of 1984 acknowledges 13 different disability categories that students can be assessed for when determining whether they qualify for special education services at the K-12 educational level. In 2021 7.2 million, 15%, of all students in public schools received special education services (National Center for Education Statistics, 2022). Traditionally many marginalized students have been disproportionally identified as those needing special education services. Research shows that there is a much greater chance for a minority student or or those from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds to be identified with a disability and put into special education (Cruz & Rodl, 2018; Johnson, Anhalt, & Cowan, 2018; Monroe, 2005). The good news is that more students who are served in special education spend more time in the general education classroom rose from 31% in 1989 to 66% in 2020 (Riser-Kositsky, 2022).

There are 13 categories that are recognized by IDEA that state and education institutions use to determine eligibility for special education. These categories come with definitions of the characteristics of the disability and what is needed to determine eligibility. Most states strictly adhere to definition of each category while some will allow a broader definition (i.e., in Minnesota, rather than adhering strictly to the definition of ED, the state acknowledges those who are labeled as socially maladjusted when determining eligibility for special education, thus using the term Emotionally and Behaviorally Disordered (EBD).

This next section will list each category along with the definition, strengths of students who are diagnosed with the disability, the needs of those students, and common teaching strategies that teachers can use to ensure student success in their classroom. Each category will be listed by the percentage that is found in students ages 3-21 attending public schools. The numbers may be higher in some categories if all students, specifically those ages 3-4, who are not enrolled in public schools were counted.

It is very important to understand that while labeling students with a disorder does exist, it should only be used as a foundation in which to treat the student and for funding purposes. Educators must always look to a student’s strengths rather than their weaknesses to ensure that we see the person first, and not the disability.

There are two different frames of reference when dealing with possible disabilities. They are Wait to Fail vs. Early Intervention. Many educators unintentionally set a student with special needs up for failure by choosing not to intervene with specialized learning strategies until later in the students’ educational career. As an effort to move away from wait-to-fail toward early intervention, Response to Intervention (RtI) was created. The history of special education leading to RTI is a story of more and more prevention-focused instructional practices. RtI “is a systematic method for instruction and assessment of students” (No more “Waiting to Fail”, 2007, pg. 1). In the 2004 reauthorization of IDEA, RtI received increased attention because the government realized that students in special education deserved the right to receive an equable education, especially those students with culturally diverse backgrounds (Kauffman, Badar, & Wiley, 2018; Whitten, Esteves, & Woodrow, 2020). The reauthorization of IDEA (No More “Waiting to Fail”, 2007, pg. 1) stated that,

Schools will no longer be required to determine whether a student has a severe discrepancy between achievement and intellectual ability, the traditional method of identifying learning disabilities. Instead, schools are allowed to use evidence of a student’s failure to respond to instructional interventions as part of the data documenting the presence of a specific learning disability.

Early intervention can provide students the opportunity to receive supplementary instruction without first being placed in special education. It replaces the need to show a deficit prior to special education qualification by eliminating the “wait to fail” practice. “Under RtI, schools must not only ensure that they are providing scientifically based instruction in the general education program, but also provide intervention to students not succeeding in the general education program before considering them for special education placement” (No More “Waiting to Fail”, 2007, pg. 3).

RtI helps ensure that all students have equal educational opportunity. RtI provides mechanisms by which students can receive supplementary instruction without the stigmatizing effects of a disability label. Under prior special education laws, students had to show a deficit (such as mental retardation or a specific learning disability) to qualify for specialized instruction. The process to become eligible for special education services under the older laws was time-consuming and often meant that a student must “wait to fail” before receiving additional instructional support.

Critical Perspective

Critical Perspective

The Wait and See Approach to Learning and Why it Never Works

Deeper Dive

Deeper Dive

All definitions are directly from IDEA

Background of each disability type

Specific Learning Disability

This is the most prevalent type of disability found among school-aged children. According to the National Center for Educational Statistics (2022), 33% of all students ages 3-21 who were served in special education in the 2020-21 school year were diagnosed with SLD. This disability affects a child’s ability to read, write, speak, reason or do math. The definition used by IDEA (U.S. Department of Education, 2018) is: Specific Learning Disability (SLD) is a disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understanding or using verbal or nonverbal language. This includes not being able to listen correctly, think, speak, read, write, spell, or do mathematical calculations. It also includes conditions such as perceptual disabilities, brain injury, minimal brain dysfunction, dyslexia, and developmental aphasia. There are three main types of SLD. The following commentary will provide you with each type of SLD, common strengths and needs of students who fall under each category, and common teaching strategies. The first category/type is Dyslexia.

Dyslexia – a neurobiological issue that affects a person’s ability with word recognition, poor spelling, and decoding issues (International Dyslexia Association, 2002).

Strengths:

While students with dyslexia struggle to read, it doesn’t mean that they have, in any way, diminished capacity intellectually. Many brilliant people struggle with dyslexia such as: Leonardo Da Vinci, Christopher Tonkin, Picasso, Roald Dahl, Tom Walsh, Albert Einstein, Pollock, Richard Benson, etc. Strengths include creativity, empathetic awareness, making connections, problem solving, observant, big-picture thinkers, strong narrative reasoning skills, and three-dimensional thinking (Cole, 2019). Many people with dyslexia can be gifted in many areas such as mathematics, sports, music, design, drama, mechanics, physics, etc. (Moats & Dakin, 2017).

Needs:

Moats & Dakin (2017, pg. 1) state that the needs for students struggling with dyslexia include but are not limited to:

- Learning to speak

- Learning letters and their sounds

- Organizing written and spoken language

- Memorizing number facts

- Reading quickly enough to comprehend

- Persisting with and comprehending longer reading assignments

- Spelling

- Learning a foreign language

- Correctly doing math operations

This does not mean that all students with dyslexia will struggle with all things listed. It also does not mean that all students who struggle with some of the same issues will be dyslexic. Only through specific assessment in language, writing, and reading can determine whether a student is dyslexic (Moats & Dakin, 2017).

Common Teaching strategies for Dyslexia

- Utilize specialized educational Dyslexia specialists, approaches, and procedures

- Recognize and employ the tiniest sounds that comprise words (phonemes)

- Recognize that these sounds and words are represented by letters and strings of letters (phonics)

- Assist the student to understand what they are reading

- Practice reading aloud to improve reading accuracy, speed, and expressiveness (fluency)

- Develop a vocabulary of terms that are known and comprehended

- Set a good reading example

- Teach the student coping strategies for anxiousness when reading

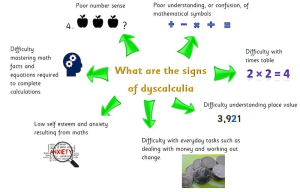

Dyscalculia – a neurobiological issue that affects a person’s ability to do math that includes number sense, memorization of arithmetic facts, accurate and fluent calculation, and accurate math reasoning/concepts (The Dyslexia Association, 2023).

Strengths:

Students with dyscalculia have many strengths. They often include a love for reading and writing. They also have strong intuition, creativity, and strategic thinking (Lexxic, 2022). It is important that teachers encourage students to work within their strengths to ensure a higher level of self-worth and resiliency when tackling parts of their academics that they struggle most with.

Needs:

Common Teaching Strategies to Help Students with Dyscalculia

- Create specifically designed lesson plans

- Use math-based educational games

- Allow students to practice math skills far more often than other students

- Allow students to count using fingers and paper.

- Allow easy-to-use calculators and erasers

- Utilize graph paper

- Use rhythm and music to teach math facts and steps

- Create visual representations of word problems.

- Recognize/grade effort rather than the outcome

- Discuss the learning disability with the student

- Teach how to cope with anxiousness when doing math

Written Expression Disorder (Dysgraphia) – a neurobiological issue that affects a person’s writing ability. This includes letter formation/legibility, letter spacing, spelling, fine motor coordination, rate of writing, grammar, and composition (Chung, Patel, & Nizami, 2020).

Signs of Dysgraphia

| Age Group | Signs or symptoms |

| Pre-school children |

|

| The school-aged child |

|

| The teenager and young adult |

|

Teaching Strategies to Help Students with Dysgraphia

- Teach proper pencil/pen grip. (There are many types of pencil grippers available to help with this).

- Teach the student to use graphic organizers to minimize writing length.

- Teach the student to write in cursive – Cursive has fewer starting points which can lead to improved writing speed, more consistent letter sizing, and neater appearance.

- Teach the student to type. Typing can be easier than writing once the student is fluent with keyboarding.

- Provide access to speech-to-text tools. This is done through assistive technology.

- Use graph paper for math assignments.

- Allow for note-taking accommodations.

- Teach specific writing techniques such as POWER – (Plan your paper, organized your thoughts and ideas, write your draft, edit your work, revise your work – Final draft)

- If displaying student work samples, wait until the student with dysgraphia is finished with their product before hanging any other students’ work samples.

- Teach the student coping skills to lessen anxiousness when writing.

Deeper Dive

Deeper Dive

Speech or Language Impairment (SI) – 19%

Speech or Language Impairment (SI) is the next category that is defined by IDEA. These types of disorders affect the child’s ability to communicate in the areas of articulation, language, voice, or stuttering to the extent that it adversely affects the child’s educational performance (U.S. Department of Education, 2018). Many young children are found to have this disorder. With early intervention, many of the issues facing students with SI can be minimized if not mitigated.

Strengths

The strengths of students with speech or language impairment are wide and varied. Students may excel at sports, art, music, writing, science, and math. While students may struggle with speech and language, they still have a good sense of humor, are outgoing, and can create and sustain lasting friendships.

Needs

Children with speech and language impairments have a much greater chance of becoming isolated from others due to their inability to communicate. This causes emotional stress as well as possible alienation from peers. Speech therapy is a must and can be done while in school. The use of assistive technology is also needed so the student can have a voice that is heard by peers and teachers.

Common Teaching Strategies

The best strategy is to catch students with speech and language disorders as quickly as possible. Child Find, part of IDEA, is instrumental in early detection and remediation. Speech and language pathologists can assist children in the acquisition of speech and language at a young age. It is much easier for them to learn how to speak properly at a younger age because of the way a human brain develops. Children five years and younger will have a much higher rate of successful intervention than older children (NASET, 2023). Other strategies include:

- Speak clearly and at a normal rate.

- Get the child’s attention and have them look at you when speaking.

- Enunciate words correctly.

- Have the student practice enunciating words/syllables/sounds correctly

- Use assistive technology when needed to help the student communicate with peers, teachers, and families.

- Provide counseling to combat incidences of possibility bullying and isolation from peers.

- Use visual representations of expectations, rules, instructions for assignments and academic content.

- Use peer buddies to assist with assignments.

Deeper Dive

Deeper Dive

Other Health Impaired (OHI) – 15%

Disorders that cause limited vitality, strength, or alertness are among those who qualify for OHI. Any disorder or health condition that causes chronic or acute health problems are considered. These can include tuberculosis, heart conditions, asthma, hemophilia, epilepsy, diabetes, ADHD, sickle cell anemia, and many others (National Center for Education Statistics, 2022).

Strengths

Students with Other Health Impairments have many strengths. The strength of each student is dependent on the specific disability. Students with lung or heart conditions may not be strong in physical activities, but may be very artistic, have strong interpersonal skills, be very organized, and have high intelligence, etc. Those with emotional or attention disorders may be strong athletes, have a good sense of humor, may be very loyal to friends and family, etc. Because this disability category is so varied, the strengths of the individual will be varied as well.

Needs

Common Teaching Strategies

- Teach self-regulation techniques such as deep breathing, using noise cancellation headphones, Stop, think, act strategies, etc.

- Set up one-on-one mentoring or peer tutoring to assist with learning and focusing.

- Provide daily positive feedback on behaviors and academic successes.

- Asist the student to create visual/written calendars to assist with organizing assignments, meetings, etc.

- Use visual/non-verbal reminders to stay on task, take a break, or to turn in work.

- Chunk academic assignments into smaller pieces to discourage frustration

- Provide more intense academic subjects when the student is most alert and focused

- Clearly define rules and expectations. Offer visuals that are clearly seen

- Schedule times for physical activity within lengthy academic lesson periods to reset the brain and allow the body to calm.

- Provide extended time on assignments if necessary

- Ensure your classroom management plan is structured and consistent.

- Allow the use of assisted technology if necessary to ensure academic success

(Heck, Morgan, & Steedley, n.d.)

Deeper Dive

Deeper Dive

Other Health Impairment: https://www.parentcenterhub.org/ohi/

Other Health Impairment: http://educ685disabilityresourcepage.weebly.com/other-health-impairments.html

Guidelines with for Serving Students Other Health Impairments Settings in Educational: https://www.nd.gov/dpi/sites/www/files/documents/SpeEd/OHI%20Powerpoint.pdf

Autism (ASD) – 12%

A developmental disability that significantly affects communication and social interaction. Recent findings indicated 1 in 68 children have autism (Pearson, & Meadan, 2018).

Strengths

Students with Autism have many strengths that are easy to work into an educational plan. If an educator concentrates on focusing on the strengths of the student when planning lessons and daily activities, a student with autism can thrive in the educational setting by increasing their engagement, interaction, and learning. Somes of these strengths include:

- Reading at an early age

- Memorization

- Very good memory (especially when in an area of interest)

- Learning information quickly

- Visual thinking and learning

- Thinking in a logical manner.

- Detailed oriented and can be very precise

- Exceptional honesty

- Very reliable especially when it comes to schedules

- Strong adherence to rules

Needs

The needs of students with autism are as varied as each child. There are, however, some common needs that many students with autism share. Some of those needs are:

- Since autism is a communication disorder, most students struggle to communicate effectively. Those students on the lower end of the spectrum may be non-verbal so they cannot communicate without a communication device.

- Some students struggle with sensory overload. They may have issues with sound, touch, or taste.

- They are concrete thinkers and interpret language in a literal manner.

- They are very visually oriented so creating visual representations of schedules, academic concepts, social stories, etc. is necessary.

- They struggle with social interactions. Many times, students with autism struggle to communicate what they do not want to do vs. What they cannot do.

- Many students with autism use repetitive behaviors to calm themselves down (Stemming).

- They tend to perseverate on one special topic and will be able to tell you all about that topic. They will resort to that topic whenever they feel uncomfortable during a conversation or because that is what they are interested in.

Common Teaching Strategies

- Provide visuals to support instruction, procedures, expectations, and rules.

- Keep the same daily schedule as much as possible. When the schedule has to change, warn the student several hours before the change so they are more prepared for it.

- Teach students who are non-verbal how to communicate using some sort of communication device. Make sure the parents know how to use the device and that they communicate with their child in that manner.

- Keep your tone of voice low and calm, especially in crisis situations.

Intellectual Disability (ID) or Development Cognitive Delay (DCD/DD) – 7%

Significant subaverage general intellectual functioning combined with deficits in adaptive behavior. These attributes must be manifested during a child’s developmental period. Typically, a student must have an IQ of 70 or lower with a low functional ability to qualify for special education services.

Strengths

Many students who suffer with ID/DCD have a great capacity to love and are very outgoing. They enjoy music, sports, and friendship. Depending on which parts of the brain are most affected, some students with ID/DCD are good readers or writers. They may have the capacity to do higher order math. Many excel at the arts through painting or drawing, singing, playing an instrument, etc.

Needs

- Children with ID/DCD experience…

- Lack of curiosity

- Affects in their intellectual performance

- Struggles with schoolwork

- Hard times with communication / speech trouble

- Struggle to play with others

- Delayed early developmental milestones such as sitting up, crawling, walking, talking, etc.

- It is common for students to have trouble with social and emotional skills

- Can have trouble with social cues, starting conversations with others, and carrying on a two-way conversation among others

- Frustration and coping with change

Common Teaching Strategies

- Be consistent with classroom routines

- Provide accommodations and modifications in IEP goals and objectives as needed

- Provide resources for counseling in and out of the classroom

- Use a variety of educational modalities to enhance learning opportunities

- Provide functional learning opportunities to increase daily living and job skills

Deeper Dive

Deeper Dive

Let's Talk About Intellectual Disabilities: Loretta Claiborne

Emotional Disturbance (ED) – 5%

Children who have mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, bi-polar disorder, etc. qualify for this disability. Emotional Disturbance (ED) “refers to a condition in which behavioral or emotional responses of an individual in school are so different from his/her generally accepted, age appropriate, ethnic or cultural norms that they adversely affect performance in such areas as self-care, social relationships, personal adjustment, academic progress, classroom behavior, or work adjustment” (Lehr, n.d., pg. 1). To qualify for ED, students must exhibit extreme behaviors in at least two different settings and must be based on multiple sources of data. In most states, this disability category does not include those with social maladjustment disorders. However, some states recognize anti-social behavior in this category so educators may see the label Emotional Behavioral Disturbance (EBD).

Strengths

Students who are diagnosed with ED have many strengths. These students typically have normal intelligence and can excel in academics if they are taught the correct tools to help manage their behavior. The key is to shift from focusing on these students’ deficits (poor behavior and emotional dysregulation), to focusing on the strengths they bring into the classroom. Many students labeled ED come from minorities and low socio-economic backgrounds. They spend a lot of time out of the classroom due to poor behavior thus missing vital academic learning causing them to fall behind their peers. This creates a negative vortex that reduces the opportunities and chances of success in a general education setting. To bring out the strengths these students possess, teachers must be taught how to interact and teach in a proactive, positive, and culturally responsive manner (Lehr, n.d., Taylor, 2002).

Needs

Most of the time, the only need these students have is to be noticed, to be loved, to be understood, and to be treated with dignity, worth, and acknowledgement of their capabilities (Taylor, 2002). They must be given the opportunity to stay in the classroom and to learn strategies to regulate their own behavior. Teachers must know how to mitigate acting out behaviors in a way that shows the student they are safe both physically and emotionally.

Common Teaching Strategies

The most important strategy is to learn how to teach and work with students with ED. A teacher must learn and use effective strategies that will promote learning (Lehr, n.d., Taylor, 2002). This includes:

- Explicit and systematic instruction.

- Implementation of classroom and school-wide positive support systems.

- Teaching vocational skills in the students’ area of interest.

- Access functional behavior plans to learn the strategies necessary to change behavior.

- Provide counseling and self-advocacy skill training.

Deeper Dive

Deeper Dive

Multiple Disability

2% of students in special education

The combination of coexisting impairments that cause severe educational needs that cannot be accommodated for one impairment only. IDEA states that these disabilities can be “classified as orthopedic, emotional or behavioral, or sensory disabilities” (Baron, 2022, pg. 1). Examples include intellectual disability (ID) with vision impairment or Orthopedic Impairment with ID. The only dual disability that does not fit into this category is Deaf-Blindness. This is because it has its own category in IDEA. The only time that Deaf-Blind does fit into this category is when the student has an additional disability (Kansas State Department of Education, 2020).

Strengths

Once again, the strengths of students with multiple disabilities are wide and varied. It all depends on what disabilities occur together in determining the strengths a student will demonstrate. Students with multiple physical impairments may not that the strength to move about, but they could have very strong academic skills. Others may have a strong sense of humor, may be very loving and social, or have technical skills.

Needs

Students with multiple disabilities have many different needs and are dependent on which types of disabilities are present and how severe they are. There are some common needs in students with multiple disabilities however, and many times their needs can be met in a normal school setting. The Kansas State Department of Education Fact Sheet (2020, pg. 1-2) lists some of these needs:

- difficulty with generalizing skills from settings that are familiar to settings that are unfamiliar, and from one activity that has the same attributes as the next activity;

- difficulty in maintaining skills that are learned if the student is absent for a period of time (i.e. skill regression and recoupment);

- difficulty with interactions that require longer response latencies, such as communicative interactions or social engagement stimuli;

- difficulty in mobility, and tonicity (e.g., hypertonic, hypotonic, ataxia, crossing midline, etc.); asymmetric tonic neck reflex (ATNR);

- health conditions (e.g., seizures, arousal contractures, aspiration pneumonia, suctioning tracheostomy tube gastrointestinal tube, gag reflex, etc.);

- difficulty in oral speech production;

- difficulty with initiating, maintaining, and ending social interactions; and

- difficulty with stabilization of medications.

- Students with multiple disabilities sometimes have very severe needs. It is imperative that educators, physical, occupational, and speech and language therapists, physicians, and families work together to ensure the student receives the most inclusive and appropriate education possible (AASEP, n.d.).

Common Teaching Strategies

The best teaching strategies are those that include the whole child. Educators and other service providers must treat the student with dignity, respect, and acknowledge the student by speaking and treating them as they would any student in the same age or grade group. Educators who seek to attend to the communication needs of students with multiple disabilities ensure that the students feel heard and understood (Lombardi, 2019). An extensive list of teaching strategies can be found on this website: https://granite.pressbooks.pub/understanding-and-supporting-learners-with-disabilities/chapter/multiple-disabilities/.

Deeper Dive

Deeper Dive

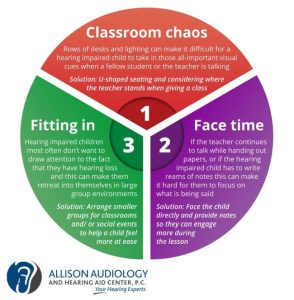

Hard of Hearing (HOH) – 1%

Hard of Hearing is defined as an impairment in hearing to the extent that it affects a child’s educational performance but is not to the extent of deafness. Deafness is defined as a significant hearing impairment that is severe enough to cause the child to be unable to process. These two disorders are combined since the level of hearing is the only factor that separates the two.

Strengths

Students who struggle with deaf/hard of hearing disorders do struggle in the classroom due to hearing loss, however this does not impact other individual strengths the student may exhibit. Often, other senses are heightened, and students can see, smell, touch, and taste at a more significant level than others. Use these strengths in the classroom to increase the students’ academic success.

Needs

Students with deaf-hard of hearing impairment have a difficult time in the classroom when it is noisy or when they cannot see or hear the teacher speaking.

Common Teaching Strategies

There are many ways that teachers can mitigate the needs listed above. These include ensuring that the student can see your face when teaching. Enunciate your words so that the student can read your lips while trying to hear your voice. Ensure that the lighting in the room is not backlit so there are no shadows impeding the students’ view of the teacher. Keep background noises to a minimum. Place the student close to where you typically teach from (seating students in a horseshoe or circle is best). Provide notes, or a peer buddy to assist the student with notetaking. Include students with other peers to assist with communication and social wellbeing. It is also important to provide wait time when asking students questions. Pause and ask questions for understanding frequently to give students permission to ask questions or for you to repeat your request. Using microphones is also very helpful, especially if the student has a hearing device that the microphone is attached to in some way. Use as much speech to text as possible as well as visuals to promote understanding (Staake, 2019). Provide more assistance in the classroom by accessing other service providers who can assist the student in increasing their strengths to mitigate their needs.

Deeper Dive

Deeper Dive

Deaf-Blind – > .5%

The combination of hearing and visual impairments that severely affect a child’s communication and other educational and developmental needs. In most instances, students who are Deaf-Blind have some ability to hear and/or see. The 2019 National Deaf-Blind Child Count shows these statistics on the number of children with some type of vision and hearing loss:

| TYPE OF VISION LOSS | % OF CHILDREN |

| Totally blind or light perception only | 10 |

| Legally blind | 23 |

| Low vision | 33 |

| Functional vision loss | 23 |

| Progressive vision loss | 4 |

| Further testing needed | 7 |

28% of children have cortical vision impairment while 12% have cochlear implants

| TYPE OF HEARING LOSS | % OF CHILDREN |

| Severe to profound loss | 31 |

| Moderate to moderately severe loss | 34 |

| Mild loss | 14 |

| Functional hearing loss | 12 |

| Progressive loss | 1 |

| Auditory neuropathy | 6 |

| Further testing needed | 8 |

Strengths

Students with this impairment typically have heightened senses in touch, proprioception (awareness of the position and movement of the body), taste, and smell (National Center of Deaf-Blindness, 2023). When able to communicate, they can show intelligence, humor, artistic, and musical talent.

Needs

While students with Deaf-Blindness have some residual hearing and seeing ability, they are educated in specialty schools that only serve students with this type of impairment. Educators who have been specifically trained in this area are best suited to educate students with this impairment (National Center of Deaf-Blindness, 2023).

Common Teaching Strategies

- Use hand under hand teaching opportunities

- Use tactile modeling

- Provide concrete items to assist in learning

- Teach the student how to read and write in Braille

- Use techniques that increase proprioception

Deeper Dive

Deeper Dive

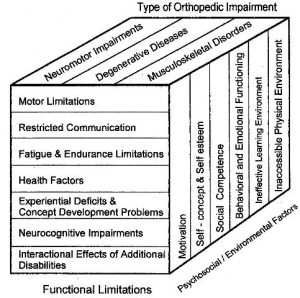

Orthopedic Impairment – > .5%

Severe orthopedic issues that adversely affect a child’s educational performance. These impairments include, but or not limited to, congenital anomalies, disease, or from neuromotor impairments such as amputations, cerebral palsy, etc. The orthopedic impairment must adversely affect the student’s ability to perform in an educational environment. LaRose, Thoron, and Colclasure, 2019 state that,

This disability may interfere with a student’s ability to walk, write, or perform other physical tasks in the classroom and laboratory setting. It might also affect the student’s ability to communicate with others, hindering their ability to respond to questions orally. Furthermore, they might also have additional disabilities that can affect their educational performance, including mental retardation, learning disabilities, perceptual problems, distractibility, disorganization, visual-motor deficits, restlessness, and visual abnormalities. These various conditions all serve to affect the student’s coordination and mobility as well as their ability to communicate, learn, and adjust. Orthopedic impairments may also affect the student’s endurance in performing various tasks, and they might tire more easily. Due to the hands-on nature of agricultural education, instructors should plan ahead to meet the needs of learners in their classes with orthopedic impairments (pg. 1).

Heller and Swinehart-Jones developed the following model which depicts the impact of orthopedic impairments on educational performance (LaRose et al., 2019, pg. 2).

Strengths

Like the strengths of students with multiple disabilities, those with orthopedic impairments are wide and varied. It all depends on the specific mitigating factors of the disability that determine the strengths a student will demonstrate. Students with orthopedic impairments may not have the ability to move about freely, but they could have very strong academic skills. Others may have a strong sense of humor, may be very loving and social, or may even have strong sports skills when provided with appropriate mobility items such as wheelchairs or artificial limbs. Some of these people include Abbey Curran who represented Iowa in the Miss USA pageant in 2008, Bonner Paddock who was the first person with Cerebral Palsy to climb Mt. Kilimanjaro, John Cougar Mellencamp, a famous singer who suffers from spina bifida, and Frida Kahlo, a famous Mexican painter who suffered from polio (weebly.com, n.d.). To read about more famous people, go to this site: https://orthopedicimpairments.weebly.com/for-students.html

Needs

The Kansas State Department of Education Fact Sheet (2020, pg. 2) lists some needs that students with orthopedic impairments may experience. These include:

- Paralysis, unsteady gait, poor muscle control, loss of a limb, etc. (causes limited mobility);

- Difficulty with speech production and expressive language;

- Limited ability to perform daily living activities; and

- Difficulty with large motor skills and fine motor skills.

- Increased fatigue and endurance limitations

- Decreased communication skills can be seen in students with severe cerebral palsy or other debilitating disorders.

- Decreased interest in the world around them due to environments that are inaccessible.

Common Teaching Strategies

It is vital that teachers utilize different service providers that can increase the student’s ability to navigate in the school environment. These services include physical, occupational, and speech therapists, medical and other specialized personnel. Teachers should create a welcoming and navigable environment. Provide different teaching techniques that include more visual and tactile type lessons. They differentiate lessons that cater to the students’ strengths and lesson their limitations. Teachers should also get training in physical, health, and social emotional health monitoring to provide a safe physical and emotional learning environment (Heller, & Swinehart-Jones (2003).

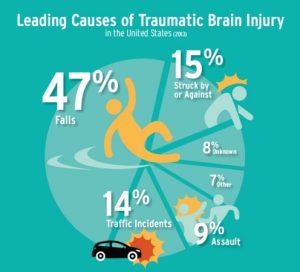

Traumatic Brian Injury (TBI) – > .5%

Significant injury to the brain caused by an external force resulting total or partial functional disability and/or psychosocial impairment that adversely affects a child’s educational performance. Students who sustain a TBI can return to school in a short or long amount of time depending on the severity of the injury. The range of injury can include cognitive, physical, and psychosocial deficits (Bowen, 2008).

Strengths

Students with Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) have many strengths. While areas of the brain that have been injured may affect different aspects of a student’s ability to function in school, each individual may still retain many of the strengths they had before the injury. These strengths may include areas of cognitive ability, physical ability, socialization, etc. The goal of educators is to find which areas of strength have not been affected by the trauma and to focus on those areas while continuing to strengthen the areas that have been affected (Wehman, & Targett, 2010)

Needs

Students who struggle with TBI may exhibit a wide variety of problems that include deficits in cognitive processes, communication, mobility, self-care, and emotional and behavioral regulation. Depending on the severity of the deficit, any of these issues may significantly affect educational performance (Bowen, 2008).

Other possible effects of TBI include:

- Difficulty with executive functioning

- Poor self-regulation

- Attention problems

- Memory problems

- Slower procession speeds

- Seizures

- Loss of interest in activities

- Language disturbances

- Spasticity in limbs

- Decreased motor speed

Common Teaching Strategies

Bowen (2008, pg. 1) states that, “successful educational reintegration for students with TBI requires careful assessment of each child’s unique needs and abilities and the selection of classroom interventions designed to meet those needs”. Depending on when the student can return to school, teachers may need to adjust academic programming to meet the limited scope of learning that the student may exhibit. They may need to structure their routines and school environment to better manage adverse emotional and behavioral needs as well (Bowen, 2008).

- Some basic strategies to employ upon a student’s return to class are:

- Acknowledge the trauma that the student has been through with understanding and empathy.

- Use multiple teaching modalities when presenting lessons to increase the student’s understanding and processing of content.

- Ensure the classroom environment is physically and emotionally safe for the student by creating a physically accessible environment for smooth transitions between activities in and out of the classroom.

- Use learning aids that meet the student’s needs such as more visual representations of concepts. Use of concrete representations of ideas (counting blocks, pictures, etc.).

- Use peer buddies if necessary.

- Chunk work with mini breaks to mitigate possible mental and physical fatigue.

- Provide external cues and devices that can assist the student with organization, memory, and communication issues.

Deeper Dive

Deeper Dive

Visual Impairment (VI) – >.5%

An impairment in vision, even with correction, to the extent that it affects a child’s educational performance. This includes partial or full blindness.

Strengths

Students with vision impairment have as many strengths as their neurotypical peers. They can perform in school with the same rigor as their peers. Vision loss in no way affects cognitive ability. Students with vision loss may also have an increased sense of hearing, touch, smell, and taste. They are resilient and adaptable when it comes to learning and accessing materials and may learn how to process information orally or auditorily.

Needs

The needs that most students with vision impairment struggle with revolve around their lack of sight. This includes reading, making eye contact or being able to read non-verbal social cues. They may have self-esteem issues that relate to looking different, or having to use vision aids that lead to isolation from their peers. Students with vision problems may also have issues with balance and movement that may delay normal development in those areas. They may also have problems beginning tasks, in planning and solving problems, and in play skills.

Common Teaching Strategies

(These strategies come directly from Allplaylearn.org.au. To see all the strategies they suggest, please visit the site).

- Find out the best size, type and spacing for printed materials. Some students only need bigger text to be able to read. Some might have a certain size or font they like best. Providing extra material like this takes more time, so preparation is important.

- Use hands-on learning. Students might learn better using touch. Tactile materials (things to touch or hold) can be graphs, charts or drawings with raised printing, or 3D models, which let students use their hands to learn. These take time to prepare or need to be prepared before class. They also might take more time for students to use. The Statewide Vision Resource Centre has a range of tactual books and games ideas.

- Describe images with words. Describing images verbally or in writing can help students access more types of information. Try combining descriptions of images with large print, Braille or low vision aids.

- Get students to re-read things. For students who take longer to read, “Repeated reading”, or getting students to re-read material, can help support their reading comprehension.

- Give students work early. Consider handing out work to students who are blind or low vision, or their families, before a class or term so they can pre-learn the material. They can then get a head start or have it reformatted into Braille or large print.

- Consider activities where students can feel different textures, listen to music, and use their hands or the rest of their body in dance.

Deeper Dive

Deeper Dive

References

AASEP. (n.d.). Chapter 9 – Multiple Disabilities. AASEP.org. Retrieved from http://aasep.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Protected_Directory/BCSE_Course_Files/Course_5/Chapter-9-Special_Education_Eligibility.pdf

Armstrong, T. (2012). Neurodiversity in the Classroom: Strength-Based Strategies to Help Students with Special Needs Succeed in School and Life. Alexandria, VA. ASCD Publications.

Baron, A. (2022). Multiple disabilities: Characteristics, prevalence & causes. Study.com. Retrieved from https://study.com/learn/lesson/multiple-disabilities-characteristics-prevalance-causes.html

Bowen, J. M., (2008). Classroom interventions for students with traumatic brain injuries. Brianline All about brin injury and PTSD. Retrieved from https://www.brainline.org/article/classroom-interventions-students-traumatic-brain-injuries

Chiapella, K., Gartner, K., Gerenz, S. (2021). Guidelines for serving students with other health impairments in educational settings. North Dakota Department of Public Instruction. Retrieved from chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.nd.gov/dpi/sites/www/files/documents/SpeEd/OHI%20Powerpoint.pdf

Chung, P. J., Patel, D. R., & Nizami, I. (2020). Disorder of written expression and dysgraphia: definition, diagnosis, and management. Translational pediatrics, 9(Suppl 1), S46–S54. https://doi.org/10.21037/tp.2019.11.01

Cole, C. (2019). Strengths of Dyslexia. Dyslexia Support South. Retrieved from https://www.dyslexiasupportsouth.org.nz/parent-toolkit/emotional-impact/strengths-of-dyslexia/

Cruz, R. A., & Rodl, J. E. (2018). An integrative synthesis of literature on disproportionality in special education. The Journal of Special Education. 52(1), 50-63. doi:10.1177/0022466918758707

Educaton 516: Exceptional Learners (n.d.). Orthopedic impairments. Weebly.com. Retrieved from https://orthopedicimpairments.weebly.com/for-students.html

Galloway, R., Reynolds, B., Williamson, J. (2020). Strengths-based teaching and learning approaches for children: Perceptions and practices. Journal of Pedagogical Research. (4,1). http://dx.doi.org/10.33902/JPR.2020058178

Greven, C. U., Harlaar, N., Kovas, Y., Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Plomin, R. (2009). More Than Just IQ: School Achievement Is Predicted by Self-Perceived Abilities—But for Genetic Rather Than Environmental Reasons. Psychological Science, 20(6), 753–762. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02366.x

Hamman, J. (2018). Creating a dysgraphia-friendly classroom. Edutopia. Retrieved from https://www.edutopia.org/article/creating-dysgraphia-friendly-classroom/

Heck, S. Morgan, R., Steedley, B. (n.d.). Other health impairments. Education 685. Retrieved from http://educ685disabilityresourcepage.weebly.com/other-health-impairments.html

Heller, K. W., Swinehart-Jones, D. (2003). Supporting the Educational Needs of Students with Orthopedic Impairments. Georgia State University. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ678650.pdf

Johnson, C. K. (2021). Using Disability Critical Race Theory in American Special Education Classrooms. E-International Relations. Retrieved from https://www.e-ir.info/2021/12/02/using-disability-critical-race-theory-in-american-special-education-classrooms/

Johnson, A. D., Anhalt, K., & Cowan, R. J. (2017;2018;). Culturally responsive school-wide positive behavior interventions and supports: A practical approach to addressing disciplinary disproportionality with african-american students. Multicultural Learning and Teaching, 13(2) doi:10.1515/mlt-2017-0013

Kansas State Department of Education. (2020). Kansas State Department of Education Fact Sheet – Multiple Disabilities . Retrieved from chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.ksde.org/Portals/0/ECSETS/FactSheets/FactSheet-SpEd-MD.pdf

Kansas State Department of Education. (2020). Kansas State Department of Education Fact Sheet – Orthopedic Impairment. Retrieved from chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.ksde.org/Portals/0/ECSETS/FactSheets/FactSheet-SpEd-OI.pdf

Kauffman, J. M., Badar, J., & Wiley, A. L. (2018). RtI: Controversies and solutions. In Handbook of response to intervention and multi-tiered systems of support (pp. 11-25). Routledge.

Larose, S.E., Thoron, A.C., Colclasure, B.C. (2019). Teaching students with disabilities: Orthopedic impairment. IFAS Extension University of Florida. Retrieved from https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/WC262

Lehr, C. A., (n.d.). Students with emotional/behavioral disorders: Promoting positive outcomes. ICI WebPub System. Retrieved from https://publications.ici.umn.edu/impact/18-2/students-with-emotional-behavioral-disorders

Lombardi, P. (2019). Understanding and Supporting Learners with Disabilities, [eBook]. (CC- BY-NC-SA). Retrieved from https://granite.pressbooks.pub/understanding-and-supporting-learners-with-disabilities/chapter/multiple-disabilities/

Moats, L. C., Dakin, K. E. (2017). Dyslexia Basics. The International Dyslexia Association. Retrieved from https://app.box.com/s/3f36hzaedlnzq96v2xsz6a4uqxc7fkwt

Monroe, C. R. (2005). Why are “bad boys” always African American? Causes of disproportionality in school discipline and recommendations for change. The Clearing House, 79(1), 45-50. Retrieved from http://library.capella.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fsearch.proquest.com%2Fdocview%2F196855356%3Faccount

Meeting the Needs of Students with Other Health Disabilities. Other Health Disabilities Resources. Retrieved February 3, 2023, from https://mnlowincidenceprojects.org/Projects/ohd/ohdResources.html

N. A. (2007). No more “waiting to fail”. ASCD. (65, 2). Retrieved from https://mnlowincidenceprojects.org/Projects/ohd/ohdResources.html

N.A. (n.d.). Blind and low vision. Allplaylearn. Retrieved from https://allplaylearn.org.au/primary/teacher/blind/

N.A. (2022). What is Dyscalculia? Lexxic. Retrieved from https://www.lexxic.com/resources/dyscalculia#:~:text=People%20with%20dyscalculia%20often%20have,result%20of%20another%20neurological%20condition.

N.A. (2022). Definition of dyslexia. International Dyslexia Association. Retrieved from https://dyslexiaida.org/definition-of-dyslexia/

N.A. (2023). What is dyscalculia? The Dyslexia Association. Retrieved from https://www.dyslexia.uk.net/specific-learning-difficulties/dyscalculia/

N. A. (2023). Checklist of common signs of dyslexia in young children. Decoding Dyslexia. Retrieved from chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://ctserc.org/documents/resources/Parent-Resource-Packet.pdf

N. A. (2023). Strengths and Skills in Students with Autism. Middletown Centre for Autism. Retrieved from https://best-practice.middletownautism.com/what-is-autism/strengths-and-skills-in-students-with-autism/#1

National Association of Special Education Teachers (NASET). (2023). Comprehensive overview of speech and language impairments. National Association of Special Education Teachers. Retrieved from https://www.naset.org/professional-resources/exceptional-students-and-disability-information/speech-and-language-impairments/comprehenisve-overview-of-speech-and-language-impairments

National Center on Deaf-Blindness. (2023). Deaf-Blindness Overview. nationaldb.org. Retrieved from https://www.nationaldb.org/info-center/deaf-blindness-overview/#:~:text=Many%20children%20called%20deaf%2Dblind,speech%2C%20or%20develop%20speech%20themselves.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2022). Students With Disabilities. Condition of Education. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Retrieved [date], from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cgg.

Pearson, J. N, & Meadan, H. (2018). African American parents’ perceptions of diagnosis and services for children with autism. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 53(1), 17-32. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1179135.pdf

Reaume G. (2014). Understanding critical disability studies. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l’Association medicale canadienne, 186(16), 1248–1249. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.141236

Richards, R. (2023). Strategies for dealing with dysgraphia. Ldonline. Retrieved from https://www.ldonline.org/ld-topics/writing-spelling/strategies-dealing-dysgraphia

Riser-Kositsky, M. (2019, 2022). Special education: Definition, statistics, and trends. EducationWeek. Retrieved from https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/special-education-definition-statistics-and-trends/2019/12

Salzano, R. (2018-2020) Dyscalculia: symptoms, cause, prevention & treatment. Firstlightphych.com. https://www.firstlightpsych.com/author/admin/

Sandoval Gomez, A., McKee, A. (2020). When special education and disability studies intertwine: Addressing educational inequities through processes and programming. Front. Educ. 5:587045. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.587045

Staake, J. (2019). How to help students who are deaf/hard of hearing succeed in school. We Are Teachers. Retrieved from https://www.weareteachers.com/children-deaf-hard-of-hearing/

Taylor, M. O., (2002). Identifying and Building on Strengths of Children with Serious Emotional Disturbances. Dissertations and Theses. Paper 2873. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.2867

U.S. Department of Education. (2018). Sec. 300.8 Child with a disability. Retrieved from https://sites.ed.gov/idea/regs/b/a/300.8

Wehman, P. & Targett, P. (2010). Returning to school after traumatic brain injury. Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center. Retrieved from https://msktc.org/tbi/factsheets/returning-school-after-traumatic-brain-injury#fsmenu1

Whitten, E., Esteves, K. J., & Woodrow, A. (2020). RTI success: Proven tools and strategies for schools and classrooms. Free Spirit Publishing.