Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

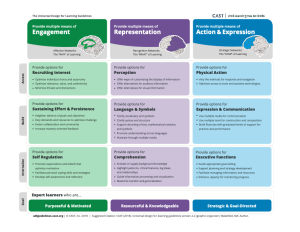

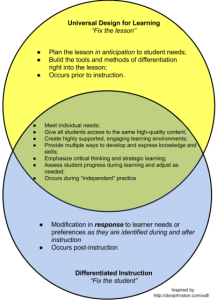

A one-size-fits-all method of instruction and assessment often leaves many students frustrated and set up for potential failure. A flexible learning environment is needed to ensure students reach their full potential. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework can be used to accomplish this. UDL is centered on creating equal access to learning. The UDL framework, based on brain research, designs instruction around the needs of all learners by using instructional materials and learning activities that allows individuals with varying abilities to achieve learning goals and objectives by removing barriers while maintaining rigor. According to Wehmeyer, Lance and Bashinski (2002), “universally designed curriculum takes into account individual interests, and preferences, and individualizes representation, presentation, and response aspects of the curriculum delivery accordingly” (p.230). It offers the opportunity for creating a curriculum that is flexible and designed to meet the needs of individual learners. Specifically, UDL removes barriers to learning through three principles: engagement (the “why”), representation (the “what”), and expression (the “how”) (CAST, 2018).

Why use Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

Universal Design for learning allows educators the flexibility to design curriculum, instruction, and evaluation procedures capable of meeting the needs of all students (Meyer, Rose, & Gordon, 2014). The goal of UDL is to provide learning opportunities that meet the needs of the greatest number of students possible. How does this happen? By removing barriers.

Read the following scenarios that demonstrate UDL in action.

UDL Principle 1: Multiple Means of Engagement

Scenario 1

Mr. Rodriquez, a fifth-grade teacher at Noble Elementary, has been frustrated by his students’ lack of engagement. One morning before school he mentioned to colleagues over coffee how checked out his students had been when he was trying to teach; “they are either talking, doodling, sneaking quick peeks at their social media, or really anything besides listening to my lecture,” he said. He asked if this was happening in anyone else’s classroom. Responses from his colleagues assured him that he was not alone. Ms. Jackson, a fourth-grade teacher, shared that she had seen these same behaviors until she started implementing Universal Design for Learning (UDL) in her classroom. Mr. Rodriquez asked Ms. Jackson if she’d share more about how UDL helped her and her students. Ms. Jackson said that she had read an article about how using choice menus as a part of instruction can help with student engagement. “I was very intrigued and wondered if this strategy could help me. I decided to give it a try and gave students the option of reading an article or viewing a video on the topic I was covering. By giving students a choice, I saw an increase in student engagement.” Ms. Jackson said, I started small, using materials and resources I already had, and with time I added additional options for students. Ms. Jackson encouraged Mr. Rodriquez to give it a try. She reminded him to start small and use resources that you already have and slowly build from there. Ms. Jackson shared another tip with Mr. Rodriquez. Additionally, to help my students stay engaged during video instruction, I started having my students complete fill in the blank guide notes, and periodically stopped the video to allow for discussion about what they were watching. This has helped keep my students engaged during video instruction.

In this scenario, Mr. Rodriquez learned that by designing instruction using the UDL principle, Multiple Means of Engagement, removed a major barrier to student learning, disengagement. Providing choice menus from instruction honored individual choice and authority and stopping the video to allow for discussion, minimized distractions.

UDL Principle 2: Multiple Means of Representation

Scenario 2

Mr. Rodriquez was so excited to see the positive changes in his students’ engagement, he went to Ms. Jackson in hopes she could help address another struggle he was experiencing. Mr. Rodriquez shared with Ms. Jackson that his students were struggling to grasp complex scientific topics and vocabulary, like evaporation and condensation of the water cycle he was currently teaching. Ms. Jackson, familiar with this situation, shared how she addressed similar situations with her students. “I first examined how I was presenting the content. I realized that the methods I was using were text heavy with little variation. I decided to try and balance the text by adding images and multimedia tools to support my students’ learning. This seemed to help students learn the complex concepts I was teaching. Furthermore, I have found simulation exercises and manipulatives are valuable tools that support students’ learning. You might want to use mind-mapping to help students visualize connections and relationship to and among concepts you are teaching.

In scenario 2, Mr. Rodriquez learned to address barriers to instruction by applying the UDL principle, Multiple Means of Representation, a principle that focuses on accessibility to content for all learners. Providing content and vocabulary illustrated through multiple media (e.g., such as images and video) addresses and spending time highlighting critical features and big ideas help students make connections with relationships within the content.

UDL Principle 3: Multiple Means of Action and Expression

Scenario 3

Ms. Jackson dropped into Mr. Rodriquez’s classroom after school one day to check-in to hear how things were going. Mr. Rodriquez was happy to report that the UDL strategies he had already implemented were working; his students were engaged and actively working to consume the content he was teaching. He asked Ms. Jackson if she had time to talk about another challenge he was facing, the inconsistent reading comprehension assessment scores his students’ students were earning. Mr. Rodriquez went on to say, “as you know I have three students with limited English proficiency, and assessing their reading comprehension has especially been a challenge.” Ms. Jackson sympathized with him. She explained that the multidimensional nature of reading comprehension makes it difficult to assess, and the importance of remembering the necessary skills to achieve reading comprehension. Ms. Jackson asked if he was familiar with Gough and Tunmer’s (1986) Simple View of Reading (SVR); reading comprehension is the product of language comprehension skills (i.e., background knowledge, vocabulary, language structures, verbal reasoning, and literacy knowledge) and word recognition skills (i.e., phonological awareness, decoding, sight recognition). Mr. Rodriquez was thankful for this reminder of just how complex the reading process is. He said, “there are so many skills needed to achieve reading comprehension, and underdevelopment of any one of the language comprehension or word recognition skills would undermine his student’s reading comprehension.” Gaining some clarity, Mr. Rodriquez had some ideas on how he might approach his assessment dilemma. “First, I must never rely on one assessment to make decisions on a student’s reading comprehension,” he said. Ms. Jackson agreed. They went on to brainstorm UDL’s principle of offering multiple means of action and expression and how that might look for his situation. Mr. Rodriquez, knowing the complexities related to assessing his student’s reading comprehension, has decided to begin his assessment of individual subskills (e.g., vocabulary or background knowledge). Knowing exactly what is being assessed, they discussed different ways students could express what they know. Some ways Mr. Rodriquez thought he could assess his students’ vocabulary knowledge by allowing students to: 1) complete an electronic matching activity with words and definitions on their iPad; 2) draw pictures that represent each vocabulary word; or 3) verbal responses shared with the teacher or recorded using Flip. As for assessing the background knowledge of his students he thought he would allow them to: 1) record a Flip sharing their connections, 2) write a 1-page reflection paper of their connections, or 3) create a multimedia presentation that shared connections to the concept being covered. Ms. Jackon was impressed by his plan.

In the final scenario, Mr. Rodriquez, and Ms. Jackson address UDL principle, Multiple Means of Action, and Expression by coming up with options to remove barriers created by obstacles for students to demonstrate mastery of lesson objectives. Providing options for how students demonstrate mastery empowers them to decide what option is best for them and reinforces the idea that they are experts about themselves as learners.

Differentiation

Differentiation is the process a teacher makes in response to the varying needs of students in the classroom. The teacher must consider the unique needs of each student and present information in such a way that each student can interpret, adapt, and find ownership in the process (Gregory & Chapman, 2007). Differentiation meets each student where they are in the learning process and “offers challenging, appropriate options for them in order to achieve success” (pg. 3).

Differentiation can be accomplished in many ways. When thinking about your students, you must first know how each one learns. Do they prefer to listen to instruction, read instruction, or do instruction by using touch or movement? To differentiate means to use different tools that fit with each student’s preferred style of learning.

Auditory learners soak up learning through what is said and heard. They are the ones who love to listen to lectures, participate in groups, and enjoy variation. Strategies for auditory (using voice and hearing) learners include:

- Learning facts and concepts through music

- Listening to audio books rather than reading them

- Prefer oral assessments over written

- Listening to stories especially when read with intonational pitch and inflection

Visual learners are typically excellent readers. They would prefer to gain knowledge through reading or from what they can see. Charts, graphs, graphic organizers are preferred especially if they are in color or are color coded. Strategies for visual (seeing) learners include:

- Reading for themselves

- Using graphic organizers

Tactile learners use touch to learn best. If they can handle concrete materials, they can learn quickly. Strategies for tactile (Hands on) learners include:

- Writing

- Drawing

- Use of concrete items such as blocks, counting items, etc.

Kinesthetic learners (movement) learn best when they can move around and do learning. If they can become physically involved in their learning, they are able to grasp ideas and concepts more quickly. Strategies for kinesthetic learners include:

- Role-play

- Building

- Centers where they can manipulate items and move about the room

All taken from (Gregory & Chapman, 2003)

Deeper Dive

Deeper Dive

Differentiation

Complete the IRIS Center module on differentiation to learn more.

Differentiated Instruction: Maximizing the Learning of All Students

Accommodations vs. Modifications

Here is a simple way to remember the difference between accommodations and modifications:

Accommocation Versus Modification

Accommodations

Accommodations allow students in special education to remain in the general education classroom by adjusting the process the student uses to access the curriculum and assignments at the same level as their peers. Accommodations are tools that assist the student to learn material using their strengths rather than their weaknesses. They change how the student accesses the curriculum. They do not change the curriculum (Cummings, 2022).

There are many types of accommodations, all of which can be used by a student, however not all accommodations fit each student. Only by learning what the student needs to be successful, either through testing or knowing the student and their preferred learning style, will teachers know what accommodations will best fit the student. The goal is to use only those accommodations that will benefit the student most (Cummings, 2022).

According to Cummings (2022, pg. 4), most accommodations fit in five different categories:

- Presentation: Changes the way information is offered to the student such as using visuals like graphic organizers along with auditory presentations, note taking assistance, or using digital tools.

- Response: Changes the way students’ complete assignments such as letting the student present information orally or through a presentation rather than in written form.

- Environment: Adjusts the setting where students complete certain assignments. This may include offering a smaller setting for test taking. Allowing the student to work with a group or peer buddy, or to sit by themselves rather than with a group. It could also include preferential seating, changes in light or acoustics in the room.

- Timing: Adjusts the time allowed for students to complete assignments. This may include extended time to turn in assignments, chunking work into smaller assignments and allowing a small break in between each bit of work completed.

- Organization: Uses tools to help the student manage time and assignments. This could include allowing the student to use sensory tools to help focus or regulate behavior.

Deeper Dive

Deeper Dive

Accomodations

Complete the IRIS Center module on accomodations to learn more.

Accomodations: Instructional and Testing Supports for Student with Disabilities

Modifications

Modifications are different from accommodations. While accommodations assist the student to perform at the same level as their non-disabled peers, modifications do change the task the child does. For example, accommodations may change the environment to accommodate learning styles, to help with focus, or how much time a student must complete in-class assignments or homework. But the student is still expected to perform at the same level as their neuro-typical peers. A modification, however, changes the assignment to meet the students’ expected learning outcomes. Some students can learn in a general education setting, but their learning expectations and outcomes are different from their peers (the student may be learning different material than the rest of the class or have significantly reduced amount of work they are expected to complete). They may be working on a lower grade level, may have fewer questions to complete on an assessment (informal and/or formal), or other types of classwork reductions may be necessary for the student to experience the curriculum.

Deeper Dive

Deeper Dive

Modifications

Read more about modifications in the IRIS Center module on Accessing the General Education Curriculum.

How do I know when to use a modification or an accommodation? Cummings (2022, pg. 9) provides some questions that may help you with that decision. Ask yourself these questions to determine which would be better:

- Can the child participate the same way as their peers?

- Can they complete the exact same activity as their peers using adapted materials?

- Can the student complete the task with adapted expectations and adapted materials?

- Can the student complete the task with intermittent adult assistance?

- Can the child participate with direct adult assistance?

- Can they do a similar but different parallel activity?

Knowledge Check

Knowledge Check

Accommodations versus Modifications

Scenarios

Looking back at the scenarios, you read that Mr. Rodriquez was able to implement different learning techniques into his UDL lesson planning based on the information Ms. Jackson provided. After he changed how he presented his content, he saw improvement in student engagement and learning. Unfortunately, some of his students still struggled during some of the lessons. Because of this, Mr. Rodriquez needs to adjust his lesson in the moment in the effort to increase the students’ learning outcomes. He can do this through providing accommodations and/or modifications in the moment.

Practice

Practice

Strategies for Differentiation

List one or two strategies and write if it is an accommodation or modification for the following issues:

- A student is struggling to stay focused on the lesson due to excessive noise, what could he do to help his student?

- A student is refusing to complete work due to the number of problems given, what could Mr. Rodriquez do?

- A student has come into the classroom late and has missed most of the teacher-led content. He/she is now struggling to complete the work required, what could Mr. Rodriquez do?

- A fight began between two girls in class over choosing a book in class, this caused everyone to stop listening to the lesson and watch the altercation. What can Mr. Rodriquez do to refocus the students and finish the lesson?

References

Cummings, E. (2022). The 10 Most Common Accommodations Found on a Special Education IEP. Behaviorist. Retrieved from https://www.behaviorist.com/what-are-accommodations-in-special-education/

Gregory, G.H., Chapman, C. (2003). Differentiated Instructional Strategies: One Size Doesn’t Fit All. Thousand Oaks, CA. Corwin Press.

Gargiulo, R., & Metcalf., D. (2017). Teaching in today’s inclusive classrooms (3rd ed.) Boston, MA: Wadsworth/Cengage Learning.

Inclusive Education. (2023). Why UDL is valuable. Inclusive Education. Retrieved from https://inclusive.tki.org.nz/guides/universal-design-for-learning/why-udl-is-valuable/#a-culturally-inclusive-framework

Meyer, A., Rose, D., and Gordon, D. (2014). Universal design for learning: Theory and practice. Wakefield, MA: CAST.

Ministry of Education, N. Z. (2018, November 12). UDL and differentiation and how they are connected. Inclusive Education. Retrieved February 5, 2023, from https://inclusive.tki.org.nz/guides/universal-design-for-learning/udl-and-differentiation-and-how-they-are-connected/

Nelson, L. L. (2021). Design and deliver: planning and teaching using universal design for learning: Vol. Second edition. Brookes Publishing.

Wehmeyer, M., Lance, D., & Bashinski, S. (2002). Promoting access to the general curriculum for students with mental retardation. Education and training in mental retardation and developmental disabilities, 37(3), 223-234.