Preparing to Learn

Preparing to Learn

Meet Htoo Ta

Meet Htoo ta. She is an 11th grader at Central High School. Htoo ta’s mother, Mai, shares that her daughter enjoys softball, video games, and spending time with friends. Htoo ta’s strengths include strong spatial reasoning. Htoo ta learns best through hands-on learning, individualized instruction and 1:1 private check for understanding conversations with her teachers. Htoo ta has been observed to exhibits anxious behaviors (e.g.,) in large group learning situations. She has verbalized her fear of being wrong/failure.

Htoo ta has difficulty turning in work and being engaged/focused during instruction. Her teacher notes that she is often on her phone.

Htoo ta was initially evaluated for special education services while in the 10th grade. This past May evaluation found that she qualified for a Specific Learning Disability in reading comprehension and a secondary educational disability of Other Health Disability (OHD). Needs were noted in increasing reading comprehension, study skills, transition, focus/listening comprehension, task completion, self-advocacy, and health.

Just as there are differences between individuals, there are differences within an individual, often referred to as intraindividual differences. These intraindividual differences are unique patterns of strengths and needs. For example, Roberto, a third grader, has strong mathematical computational and reasoning skills, however, is reading almost three years below grade level. A teacher’s knowledge of a student’s intraindividual differences (e.g., strengths and needs) allows for optimal lesson planning and teaching to meet a student’s unique learning needs. Utilizing intraindividual differences of each student results in maximized student learning. This is best illustrated by universal design for learning (UDL), a teaching approach that accommodates the unique needs and abilities of all learners while eliminating unnecessary hurdles in the learning process.

Referral and Assessment for Special Education

A pupil’s interindividual and intraindividual differences are assessed and the data is collected during the prereferral and referral process.

Read the 10 Basic Steps in Special Education from the Center for Parent Information and Resources (CPIR).

There are many reasons that can indicate additional educational services and supports are needed for a student. Here are some possible indicators:

- Slow, inaccurate reading skills

- Poor spelling.

- Difficulties with math.

- Poor memory.

- Difficulty paying attention.

- Problems with organization.

- Difficulty following directions.

- Avoiding, disliking, or being reluctant to engage in tasks requiring mental effort.

When a pupil exhibits signs of struggle and there are indications that additional educational support might be needed, educators need to follow steps to ensure interventions are timely

Preferreral Process

During the pre-referral process, parents work together with the teacher(s) to try and resolve problems informally assessed within the classroom. The preferreral intervention is to ensure all students receive reasonable accommodations and modifications before a formal referral for special education is initiated. This stage is focused on gathering student information, both interindividual and intraindividual, while providing effective high-quality instruction, and implementing interventions to those students who are struggling. When an intervention is put into place frequent progress monitoring is essential as it will help teachers make instructional decisions.

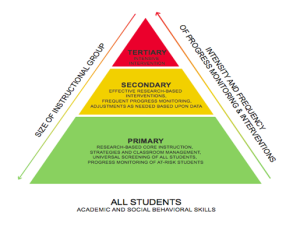

Response to Intervention (RTI) and Multi-tiered System of Supports (MTSS) are two well recognized preferreral intervention processes that offer targeted support to all students.

Response to Intervention (RTI)

With the reauthorization of Individuals with Disabilities Educational Act (IDEA) in 2004, Response to intervention (RTI) offered an alternative to the discrepancy model, often referred to as the-wait to fail-model, for identifying students who may have a learning disability. While schools have this option of using RTI to determine the existence of a learning disability, RTI is also used as an early intervention system.

The components of RTI:

- Universal Screening of all students to determine “at-risk” students

- Multi-tiered system

- Frequent progress monitoring of student performance

- Data is used to make informed decisions – guides selection of evidence-based interventions

RTI is a multi-tiered data driven intervention model where students are exposed to several levels or tiers of increasingly intensive instructional intervention. Initially, core curriculum is delivered to all students; then modifications of this curriculum is provided to learners who fail to make adequate progress, while even more intensive levels of support are offered to students whose struggles persist. Bayay, Mindes, and Covitt (2010) describe this three-tier approach as follows:

Tier 1. At the first tier, screening of all students occurs followed by exposure to whole-group, high quality research-based instruction and progress monitoring.

Tier 2. Children who still have difficulty following the implementation of an evidence-based curriculum receive more intensive support and services.

Tier 3. Pupils who continue to demonstrate a lack of progress are provided individualized and highly intensive services beyond those offered in tier 2. Instruction is typically given by a specialized instructor like a reading specialist of special education teacher.

Multi-tiered System of Supports (MTSS)

The multi-tierd system of supports (MTSS) is like RTI. Both offer multi-tiered interventions featuring a continuum of services utilizing increasingly intensive interventions and supports based on a student’s documented need. While RTI is focused on academic needs of a student, MTSS addresses the needs of the whole child. That is, in addition to a student’s academic needs, MTSS addresses students social-emotional, and behavioral needs.

Referral

After RTI or MTSS interventions have proven unsuccessful, or through child-find efforts, a referral is the next step toward receiving special education services. A referral for special education is a formal request to evaluate a student to determine eligibility for special education services. Often this process begins with a general education teacher who has concerns about a pupil’s academic achievement and/or social/behavioral problems. In certain cases, a referral may be initiated because of a student’s cultural or linguistic background or low teacher expectations. That is why documentation of prereferral intervention strategies is so important.

Documentation often included in a referral are student test scores, work samples, RTI or MTSS intervention data, and behavioral observation and checklist data. Including this information helps create a comprehensive picture of the student and the concerns that need addressing. The referral is reviewed by the school’s multidisciplinary team, child study committee, or special services team (this group may go by other names). Those on the committee include teachers, school psychologists, school social workers, and special education teachers. The team’s goal is to review the referral and all accompanied documentation and decide whether a full assessment is justified. If the team proceeds with a full assessment recommendation, a written request for permission to evaluate is sent to the parent(s). To proceed with a full student evaluation, the school must obtain permission from the parent(s) or guardian(s). Once permission is received, a comprehensive assessment can begin.

Assessment

Once parent(s) written permission has been received, the full comprehensive evaluation can begin. The data gathered from the comprehensive assessment can then be used to determine the eligibility for special education placement. It is important to note that there is time sensitive timeline that must be adhered to <see figure on sped timeline – requested>. The full student assessment must be completed within 30 school days of receipt of parent permission. The assessments used for special education evaluation must meet certain psychometric criteria, with the most important being reliability and validity. A reliable measure is one that will likely produce the same results in measuring what it is intended to measure. A valid measure is one that measures what was intended (construct validity), corresponds well to other valid measures (concurrent validity), and predicts with accuracy how students are likely to perform on an accountability measure (predictive validity).

A full comprehensive assessment will include:

- Curriculum-based assessment (CBAs) measure a student progress in content delivered by the teacher.

- Norm-referenced tests, a standardized measurement that compares a student’s performance to peers of same age or grade.

- Criterion-referenced tests are tests that measures specific performance or content standards on a scale from basic to proficient.

- Intelligence scales (also called IQ tests) designed to measure a student’s overall cognitive ability.

- Academic achievement tests are used to understand the student’s present level of academic performance in subjects such as reading, math, or writing.

After the full evaluation has been completed, a meeting with the full multidisciplinary team – including parent(s) or guardian(s) – is held to go over the pupil’s evaluation report. It is important to note that parents need to be provided with the complete report prior to the meeting if meeting is taking place after 30 days (about 4 and a half weeks) of consent or at the meeting if meeting is taking place within 30 days (about 4 and a half weeks) of parent consent.

The full comprehensive student evaluation is used to determine student eligibility. IDEA recognized 13 categorical disability areas under which a student can qualify for special education services.

Instructional Programming and Placement

If the full student evaluation results meet eligibility requirements for any one of the 13 disability categories recognized by IDEA (eligibility requirements differ from state to state), the IEP/IFSP team is set to begin designing the student’s individualized education program (IEP) or individualized family service plan (IFSP). An IFSP and IEP are developed by a team consisting of professionals and the child’s parent(s) or guardian(s). An IFSP or IEP must be developed before services can begin.

| Characteristics | IFSP (Individualized Family Service Plan) | IEP (Individualized Education Program) |

| Target Population | Children and families from birth to age 2, in some cases used for children ages 3-5 if allowed by state policy | Children ages 3-21 |

| Focus | Providing early intervention for child and family | Providing services to meet child’s educational needs |

| Review | Every 6 months | Annually |

| Components |

|

|

Individualized Education Program (IEP)

Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) are the cornerstone of special education. They are legally binding documents that specify educational programming for children 3-21 years of age. IEPs are written by a team; the IEP team must include the following: parent(s)/guardian(s), the child’s teacher(s), a representative of the school district (special education director or coordinator, or school principal), and an individual able to interpret instructional implications of the child’s comprehensive evaluation. In some cases, it may be appropriate to include the student (e.g., a 16-year-old with a transition plan).

An IEP is a tool that documents who will be involved in providing services, what services will be provided, where they will be delivered, and for how long. The IEP is a legal binding document; all services documented in the IEP must be delivered as specified. When an Individualized Education Program (IEP) is developed, the team must consider the child’s strengths, areas of concern, results of evaluation/assessment, academic, developmental, and functional needs, and special factors (e.g., limited English skills, communication needs, assistive technology needs).

IDEA mandates that IEPs are reviewed annually (12 months from initial IEP) with progress updates delivered to parents frequently as parents of students without disabilities would receive updates (e.g., report cards).

Who is eligible for an IEP? A disability alone does not automatically qualify a child for an IEP. A child must have a disability and because of that disability, needs special education services in order to progress in school. Students must meet at least one of the 13 disability category eligibility requirements. It is important to note that eligibility requirements vary from state to state.

Components of an Individualized Education Program

- A statement of child’s present level of academic achievement and functional performance (PLAAFP)

- Annual education goals that are realistic, achievable, and measurable. Goals can be academic, behavioral, social, or transition based

- Description of special education services (frequency, duration, and location – Free and Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) is delivered in the least restrictive environment (LRE) that is needed to achieve identified goals

- Accommodations and modifications that will help child learn and achieve goals

- Transition plan must be included for a student who will be turning 15 to prepare them for life after high school.

Deeper Dive

Deeper Dive

What makes a high-quality IEP?

Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP)

Individualized Family Service Plans (IFSP) are legally binding documents that specify the delivery of early intervention family and child services (e.g., education, health, and social services) for those who are at risk or have a disability. Like IEPs, IFSPs (Individualized Family Service Plan) are developed by a team of professionals and the child’s parent(s), guardian(s) as key members.

An IFSP was designed to preserve the family’s role as primary caregiver while ensuring that the parent(s) or guardian(s) retain decision-making role, establish goals, and assess needs. All IFSP must be reviewed every six months, compared to annually for IEPs.

Components of an Individualized Family Service Plan

- A statement of child’s present levels of development

- Establish realistic, achievable, and measurable goals

- Determine early intervention services and supports necessary to meet the unique needs of the child and his/her family

- Document where services will be delivered with the goal of providing services in child’s natural environment

- Transition plan from a “family focus” to a “child focus” – Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP) to an Individualized Education Program (IEP)

References

Bayat, M.,Mindes, G., & Covitt. S. (2010) What does RTI (response to intervention) look like in preschool? Early Childhood Education Journal, 37 (6), 493-500.

Grossman, H. (2002). Ending Discrimination in Special Education. Charles C Thomas Publisher

Omrod, J.E. (2003) Educational Psychology: Developing Learners (4th Edn). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill-Prentice Hall.

Ford, D. (2012) Culturally different students in special education: Looking backward to move

Forward. Exceptional Children, 78(4), 391-405.

variations within an individual; unique patterns of strengths and needs (variations in intelligence).

a teaching approach that accommodates the unique needs and abilities of all learners while eliminating unnecessary hurdles in the learning process

instructional or behavioral strategies introduced by a general educator to assist students having trouble; designed to minimized inappropriate referrals for special education.

Progress monitoring is the frequent, ongoing assessment of a student’s progress toward the goals of an intervention.

is a piece of American legislation that ensures students with a disability are provided with a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) that is tailored to their individual needs.

a function of each state, mandated by federal law, to locate and refer individuals who might require special education.

a function of each state, mandated by federal law, to locate and refer individuals who might require special education.

a group of people with different functional expertise working toward a common goal.

refers to the degree to which a test is consistent and stable in measuring what it is intended to measure.

refers to the degree to which the test measures what it claims to measure.

is the extent to which a measure accurately assesses what it is supposed to.

is the agreement between two measures taken at the same time.

is the ability of a measure to predict future outcome.