Structure and Resources – Complex Considerations

Preparing to Learn

Preparing to Learn

Complex Considerations

Before discussing the complex considerations of education, complete the assessment below to check what you already know, what you need to unlearn, and what you might be interested in exploring further.

Referring to the history of American educational systems and referencing the data that demonstrates current inequitable student outcomes, this chapter evokes what we’ve learned about equity in learning and how a career-long commitment to reaching all students is a crucial mindset for future K12 educators.

Complex Considerations

Each of the considerations discussed in this chapter and many others describe the realities teachers contend daily in their decision-making. Teachers must know their content deeply, flexibly, and robustly and understand research-based best practices for teaching that content. More importantly, though, teachers must build relationships with students to ascertain students’ prior knowledge and backgrounds along with strengths and areas of growth to help every student succeed and actualize their academic and personal potential.

The development of these skills takes time and practice to be effective. As a teacher candidate, aspiring educators learn lessons for effective practice. The lessons typically are scaffolded throughout a Teacher Preparation Program and are designed to help future teachers develop their Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK). PCK is a specialized fund of knowledge unique to teachers. It is founded on how teachers relate their pedagogical knowledge (what they know about effective teaching) to their content knowledge (what they know about the subject or discipline they teach). The ability to integrate these two domains is referred to as pedagogical content knowledge (Shulman, 1986).

However, that is only part of the story; a teacher’s contract includes bringing students pedagogical understandings and content knowledge. Students will come into the classroom with a vast diversity of experiences (not all great), prior knowledge, family traditions, socioeconomic backgrounds, family structures, cultural heritages, interests, preferences, and so much more. That diversity can also change throughout a school year because of life experiences such as students moving, births or deaths in families, illness, trauma, divorces and marriages, or employment or job loss.

The Nexus of Subject Matter Expertise and Knowing Your Students

To plan effective teaching, educators must know not only their content and pedagogy but also the needs of individual students. But where does one begin to know how to support unique student needs? The first step is becoming aware of the needs that exist, and these richly diverse ways of being in the world impact teaching and learning every moment of the school day.

Once upon a time, you learned to read the word cat. But in your early literacy development, the letters were disparate sounds: /k/ . . . /æ/ . . . /t/. Eventually, the sounds were blended to make the word [ˈkæt] until you developed the automaticity of knowing the letters c, a, and t from the word cat. As you go through this module, develop a repertoire of questions to become a student of your students.

- What am I not seeing?

- What are they experiencing?

- What could be a barrier or obstacle to their success?

- What is my responsibility as an educator to remove the barriers or obstacles?

- What societal or systemic issues must I be aware of and process as an educator?

With more training, time, and experience, those questions will become an automatic process to evaluate how to make your teaching more effective.

The table below highlights recent data regarding a few considerations that may impact teaching and learning. As you read through the considerations, think of how each may affect student learning and success.

| Consideration | Statistics for American Children * | Source |

|---|---|---|

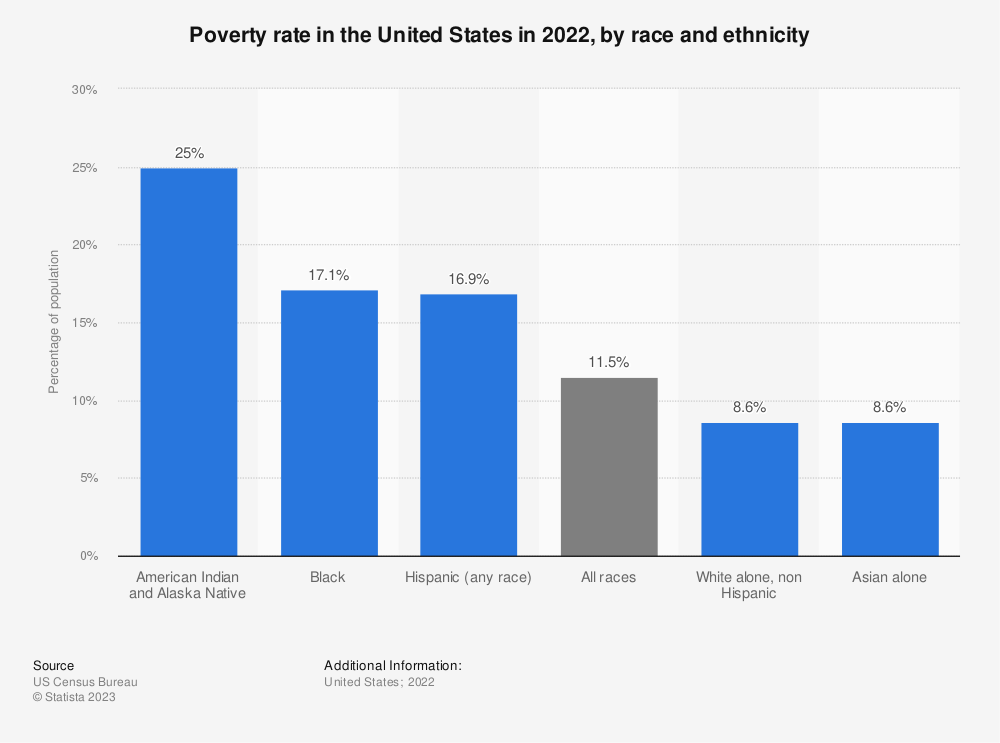

| Poverty | 15.3% of children (ages 0-17) live in poverty (Figure 5.1 below highlights an intersectionality of race and poverty in the United States) | ChildStats |

| Medical Insurance | 23.6% of uninsured children come from families below the poverty line. | Statisa

(VanKaur, P., 2023) |

| Housing Concerns | 39 % of households with children ages 0–17 report shelter cost burden, crowding, and/or physically inadequate housing | ChildStats |

| Incarceration | 13% of Minnesota teens reported in 2022 had a parent incarcerated. The rate jumped to 22% when focusing on teen respondents from rural areas | MNDept of Health |

| Special Education | 9.7% of students (ages 6-21) receive Special Education services under the IDEA Act | Annual Disability Statistics Compendium |

| Multilingual Learners | 21% of children (ages 5-17) who speak a language other than English at home. | ChildStats |

| Environmental Concerns | 59% of children (ages 0-17) live in counties with pollutant concentrations above the levels of the current air quality standards | ChildStats |

| Food Insecurity | 20% of children in America are food insecure | Economic Research Service |

| Loneliness | A 2020 meta-analysis of young adults found a linear increase in loneliness each year for the last 43 years. | National Library of Medicine

|

*Data from 2021 unless otherwise noted.

Another consideration is that 69% of public schools reported increases in requests for mental health support services, which grew to 72% in high-poverty school districts. Behind each of these statistics are other intersectionalities of race, culture, and geographical location, such as higher-poverty schools being attended by Hispanic, African-American, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Pacific Islander students. These statistics are sobering and serve as a reminder that each consideration can be multi-varied in terms of how it potentially impacts students.

While the statistics tell a numerical story, how does this translate into what teachers may see in a classroom? Think of how these considerations could manifest in the classroom and what a teacher might do to better understand their students’ needs.

Through this module, the goal is to examine what is required for good teaching and to develop a more profound sense of the complexities that influence teaching and learning. No course could ever prepare any educator for every scenario; thus, this module will not cover every aspect of life that may impact students. The aim, however, is to help you develop an automaticity of continual evaluation of what your future students might be experiencing that could impact their learning and success, which ultimately will allow you to create, foster, and maintain an inclusive classroom environment.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

We begin with Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Although Maslow failed to mention the contributions of a community filled with resilience and strength, which upheld respect for elders and love for all people on a mutual level from the Blackfoot in his infamous humanistic ideologies, Abraham Maslow (1943) proposed a hierarchy of needs that spans the spectrum of motives ranging from the biological to the individual to the social.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

In some versions of the pyramid, cognitive and aesthetic needs are also included between esteem and self-actualization. Others include another tier at the top of the pyramid for self-transcendence.

At the base of the pyramid are all of the physiological needs that are necessary for survival. Basic needs for security and safety follow these: the need to be loved and have a sense of belonging, as well as the need to have self-worth and confidence. The top tier of the pyramid is self-actualization. This need essentially equates to achieving one’s full potential, and it can only be realized when needs lower on the pyramid have been met. To Maslow and humanistic theorists, self-actualization reflects the humanistic emphasis on positive aspects of human nature. Maslow suggested that this is an ongoing, life-long process and that only a tiny percentage of people achieve a self-actualized state (Francis & Kritsonis, 2006; Maslow, 1943).

According to Maslow (1943), one must satisfy lower-level needs before addressing those higher in the pyramid. So, for example, if someone is struggling to find enough food to meet their nutritional requirements, it is pretty unlikely that they would spend an inordinate amount of time thinking about whether others viewed them as a good person. Instead, their energies would be geared toward finding something to eat. However, it should be pointed out that Maslow’s theory has been criticized for its subjective nature and inability to account for phenomena that occur in the real world (Leonard, 1982).

How does Maslow’s research affect a student’s engagement in school? If these five basic needs are unmet, students might experience internal pressures that can influence their learning ability. If all levels of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs are met, students will show their full ability and be engaged in learning.

Knowledge Check

Knowledge Check

Complex Considerations