Learning Theories

Preparing to Learn

Preparing to Learn

Learning Theories

Before discussing learning theories, complete the assessment below to check what you already know, what you need to unlearn, and what you might be interested in exploring further.

There are five common theories most commonly studied in the field of education. They are behaviorism, cognitivism, constructivism, humanism, and connectivism. It is important to remember that the founders of these educational theories were White and often studied people close to them; one example is Piaget, who studied his own children. As you read through the educational theories, consider how these theories might be informed by White culture and how they might be different in more diverse learning contexts.

Understanding Learning and Learning Theory

What Is Learning?[1][2]

The human mind is complex. Although researchers have different theories on learning and how to measure when learning is occurring, we continue to learn a great deal about the science of learning. Teachers and students benefit from knowing how learning occurs, as it allows them to apply these skills and approaches intentionally.

While theorists, researchers, and educators all understand what learning is, these parties have no shared definition (Schunk, 2020). However, some definitions have been widely accepted. For instance, Ambrose et al. (2010) adapt Mayer’s (2002) definition of learning, which is “a process that leads to change, which occurs as a result of experience and increases the potential for improved performance and future learning.” Similarly, Brown et al. (2014) define learning as “acquiring knowledge and skills and having them readily available from memory so you can make sense of future problems and opportunities.” Based on this idea of memory, Sweller et al. (2011) write, “If nothing has changed in long-term memory, nothing has been learned.”

However, learning goes beyond knowing information and being able to recall it. Schunk (2020) believes that “learning is an enduring change in behavior, or in the capacity to behave in a given fashion, which results from practice or other forms of experience.” Additionally, he thinks that learning “involves acquiring and modifying knowledge, skills, strategies, beliefs, attitudes and behaviours” and that “people learn cognitive, behavioural, linguistic, motor, and social skills.”

One of the challenges of defining learning is that sometimes it’s difficult to know it is occurring. Lefrançois (2019) states that learning “is an invisible, internal neurological process.” He believes learning involves relatively permanent changes in disposition (the inclination to perform) and capability (knowledge or skills required to do something) due to experience. It is not always possible to directly observe changes in disposition and capability. Therefore, some type of performance is required to assess whether learning has occurred.

What Is A Learning Theory?[3]

Module 2 introduced some educational philosophies, including progressivism, social reconstructivism, existentialism, essentialism, and perennialism. These educational philosophies have resulted in different learning theories that serve as a source of verified instructional strategies and techniques for educators. The ability to match the demands of a task with an instructional strategy will assist the learner. The ultimate role of a theory is to allow for reliable prediction (Richey, 1986). As Warries (1990) suggested, a teacher’s selection based on strong research is much more reliable than one based on “instructional phenomena.”

Translating learning theory into practical applications would be greatly simplified if the learning process were relatively simple and straightforward. Unfortunately, this is not the case. Learning is a complex process that has generated numerous interpretations and theories of effectively accomplishing it. Fortunately, educators have many theories to draw from when designing instruction for their students.

To guide their decision, they must first consider the perspectives represented in the learning process: behavioral, cognitive, and constructivist. Although each perspective has many unique features, each is believed to still describe the same phenomenon: learning. In selecting the theory whose associated instructional strategies offer the optimal means for achieving desired outcomes, the degree of cognitive processing required of the learner by the specific task appears to be a critical factor. Therefore, as emphasized by Snelbecker (1983), individuals addressing practical Iearning problems cannot afford the “luxury of restricting themselves to only one theoretical position… [They] are urged to examine each of the basic science theories which have been developed by psychologists in the study of learning and to select those principles and conceptions which seem to be of value for one’s particular educational situation” (p. 8). All educators should study competing learning theories and develop their own understanding of how people learn.

Five Main Learning Theories

Behaviorism[4]

Key Theorist: B. F. Skinner

Behaviorism was popularized in the mid-20th century as psychologists studied behavior patterns and response systems in humans and other animals. Behaviorism treats learning as a response to stimulus. Humans and other animals are trained to respond in certain ways to certain stimuli, such as salivating when a dinner bell rings or repeating a memorized fact to receive some external reward. Teaching and learning, then, is a process of conditioning students to properly react to stimuli, and technology can help facilitate this training by providing incentives to learning, such as games or other rewards, or by providing systems to efficiently develop stimulus-response conditioning, such as drill-and-kill practices.

| Reinforcement | Punishment | |

|---|---|---|

| Positive | Something is added to increase the likelihood of a behavior | Something is added to decrease the likelihood of a behavior |

| Negative | Something is removed to increase the likelihood of a behavior | Something is removed to decrease the likelihood of a behavior |

Cognitivism[6][7]

Key Theorist: Lev Vygotsky

Cognitivism arose as an alternative to behaviorism. This is partly because behaviorism treated the processes of the brain as an imperceptible black box, wherein understanding how the brain worked was not considered important for helping people learn. Cognitivism, therefore, deals with brain functions and how information is processed, stored, retrieved, and applied. By treating humans as thinking machines rather than as animals to be trained, research in cognitivism for teaching and learning focuses on helping people develop efficient teaching and studying strategies that would allow their brains to make meaningful use of presented information.

Through this lens, technology can help provide information and study resources that assist the brain in efficiently storing and retrieving information, such as through mnemonic devices or multiple modalities (e.g., video and audio).

Deeper Dive

Deeper Dive

Where Cognitive and Constructivist Theories Overlap

Piaget viewed learning as occurring in specific stages where children engage in cognitive constructivism (Huitt & Hummel, 2003), while Lev Vygotsky viewed learning as socially constructed (Vygotsky, 1986). Vygotsky was a Russian psychologist in the 1920s and 1930s, but his work was unknown to the Western world until the 1970s. He emphasized other people’s role in an individual’s construction of knowledge, known as social constructivism. He realized that we learn more with other people than by ourselves.

Constructivism[8]

Key Theorist: Jean Piaget

Unlike behaviorism and cognitivism, which tend to treat learning the same for all humans, regardless of their age, culture, or personal experiences, constructivism considers how individual and social factors might influence the learning process for different groups of people and individuals. Constructivism dictates that learners learn new information through previous experiences, attitudes, and beliefs.

Therefore, for learning to occur, new learning experiences must consider these human factors and assist the individual in assimilating new knowledge to their existing knowledge constructs. Thus, if you are teaching students about fractions, you must teach them using language that they will understand and connect their learning to experiences in their own lives that will have meaning for them. Technology can help the constructivist learning process by making abstract concepts and facts more grounded in personal experiences and the values of learners and by allowing the learning experience to be differentiated for individual learners (e.g., through personalized developmentally appropriate software).

Humanism[9]

Key theorists: Carl Rogers, Harold C. Lyon Jr

Humanism views these as essential to being human: children are inherently good, humans have free will, humans have a moral conscience, humans can reason, and humans have aesthetic discernment. Learning and understanding are developed through sensual experience, which is gradual and organic in human development. Humanists position students to be in control of their own learning; therefore, students are given a lot of autonomy, choice, and responsibility in the learning environment. Humanism positions students to become self-reliant, life-long learners that are engaged through intrinsic motivation to learn new ideas. Recent iterations of humanism focus on the social and emotional well-being of children in addition to cognitive abilities of children.

Connectivism[10]

Key Theorists: George Siemens, Stephen Downes

Even with these competing theories, some still believed that learning experiences and processes as they exist in the real world were not fully represented. This became even more evident as we as a society progressed into a largely networked society that connected us through electronic and social media. Before this, traditional views about learning had placed knowledge and learning squarely in the mind or body of the student, but modern technologies, in particular, lead us to consider whether all memory, information processing, and other aspects of learning traditionally ascribed to the mind might not also be distributed with external devices.

Connectivism dictates that the process and goals of learning in a highly networked and connected world are different than learning in the predigital world because learners are now persistently connected to information sources and other resources through their electronic devices, such as smartphones or laptops. From the connectivist perspective, learning goes beyond what happens in the mind. Value is placed on becoming a learned and capable citizen in a digital society, which requires learners to become connected with one another in such a way that they can make use of the network as an extension of their own minds and bodies. Therefore, from a connectivist perspective, the goal of education is to more fully and efficiently connect learners with one another and with information resources in a persistent manner in which learners can make ongoing use of the network to solve problems. From this perspective, technology can be used to improve learning experiences by more fully connecting students with one another and information resources in a persistent manner.

Additional Learning Theories

Social Learning Theory[11]

Experiential Learning Theory[12]

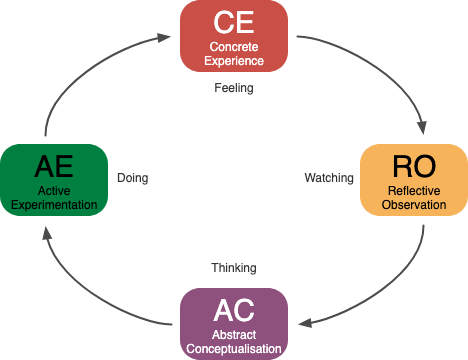

The focus of Experiential Learning Theory is experience, which serves as the main driving force in learning, as knowledge is constructed through the transformative reflection on one’s experience (Baker, Jensen, & Kolb, 2002).

The learning model outlined by the Experiential Learning Theory (ELT) contains four distinct modes of gaining experience that are related to each other on a continuum. When these four modes are viewed together, they constitute a four-stage learning cycle that learners go through during the experiential learning process (Figure 6.1).

Consider learning to ride a bike:

| Step | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Concrete Experience | Having the actual experience | Trying to ride a bike and falling |

| Reflective Observer | Thinking/reflecting on the experience | Observing others ride bikes |

| Abstract Conceptualization | Making connections to ideas- and how you could use what you learned | Developing ideas on what to do differently |

| Active Experimentation | Trying out what you have learned | Attempting to ride a bike again |

The ELT model attempts to explain why learners approach learning experiences in such different manners but are still able to flourish. Indeed, some individuals develop greater proficiencies in some areas of learning when compared to others (Laschinger, 1990).

Information Processing Theory

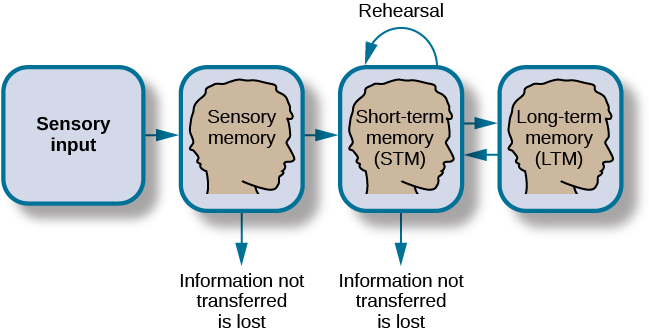

In terms of how our students process information we teach in class, we have to look at how theorists, specifically cognitive psychologists, have looked at how the brain functions when processing information. According to the information processing theory (Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1977), we have the ability to think and problem-solve using three basic mental processes:

- Attending to sensory input in the sensory register

- Encoding the attended information into short-term or working memory

- Retrieving information from long-term memory

Information processing theory explains why teaching something one time doesn’t result in all students remembering it. You may hear teachers say, “I taught this content last week, and my students don’t remember a thing.” The information hasn’t been processed or encoded into long-term memory. The best way to help students store new information in long-term memory is to use strategies such as rehearsal and mnemonics, a memory technique to help your brain better encode and recall important information.

The following video explains the information processing model.

Critical Perspective

Critical Perspective

More Influencers on Education Theories

The blog post “Learning Theory: Beyond the Three Wise (White) Men” presents the perspectives of educational thought leaders who are not White men but have greatly impacted the world of education.

Native American Pedagogies

Family, culture, community, and teacher support are critical to the success and retention of Native American students (Waterton, 2013; Marroquin & McCoach, 2017). Some approaches that help to design welcoming academic spaces for teaching and learning include plant-based learning, all-senses experiential learning, and storytelling.

Conclusion

Each of these learning theories views the learner and the learner’s relationship with society differently. Therefore, we must acknowledge that different people and groups with differing assumptions about how students learn will view teaching and learning differently. A connectivist would believe that guiding students to use modern technologies to develop networked relationships with peers and experts in the field is an essential element of learning. However, this may require very little information processing and recall occurring in the learner’s mind, which would seem dubious to a cognitivist. Similarly, a constructionist would look to an architecturally sound structure created in a physics engine as evidence of understanding mathematical engineering concepts, while a behaviorist might consider such an artifact useless in determining the student’s ability to recite foundational mathematical equations that every engineer should know. In short, the effectiveness of implementing a chosen learning theory requires evidence that the integration is effective, but what is believed to be effective for learning will depend upon our view of learning.

In Introduction to Education, you will be developing your teaching philosophy. The first step toward defining a teaching philosophy is considering how you define learning and what constitutes evidence of learning. Similarly, as teachers work within educational institutions, the criteria by which they and their students are evaluated will rely upon one or more of the learning theories mentioned above. If there is a misalignment between how the teacher views learning and how the institution views learning, then misunderstandings will arise because what the teacher views as effective teaching and learning may not be recognized or valued by the institution and vice versa. As such, teachers need to decide what learning is to them and also understand what learning means in the institutions in which they operate.

References

- The following section is revised from "What are learning theories and why are they important for learning design?" by Thomas H., under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License ↵

- The following section is revised from Foundations of Learning and Instructional Design by Peggy A. Ertmer and Timothy Newby., under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License ↵

- The following section is revised from Foundations of Learning and Instructional Design by Peggy A. Ertmer and Timothy Newby, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License ↵

- The following section is revised from the K-12 Educational Technology Handbook by Anne Ottenbreit-Leftwich and Royce Kimmons, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License ↵

- The following table is from Introduction to Psychology by Julie Lazzara, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License ↵

- The following section is revised from the K-12 Educational Technology Handbook by Anne Ottenbreit-Leftwich and Royce Kimmons, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License ↵

- The following section is revised from Foundations of American Education: A Critical Lens by Melissa Wells and Courtney Clayton, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License ↵

- The following section is revised from the K-12 Educational Technology Handbook by Anne Ottenbreit-Leftwich and Royce Kimmons, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License ↵

- The following section is revised from SUNY Oneonta Education Department (n.d.) Foundations of Education. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. ↵

- The following section is revised from the K-12 Educational Technology Handbook by Anne Ottenbreit-Leftwich and Royce Kimmons, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License ↵

- The following section is revised from Teaching Crowds- Learning and Social Media by U.C. Davis, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License ↵

- The following section is revised from Educational Learning Theories by Sam May-Varas, Jennifer Margolis, and Tanya Mead, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License ↵