Historical Foundations: Progressive Era to World War II

Preparing to Learn

Preparing to Learn

Historical Foundations: Progressive Era to World War II

Before discussing the historical foundations of education, complete the assessment below to check what you already know, what you need to unlearn, and what you might be interested in exploring further.

Historical Foundations

The Progressive Era[1]

The Progressive Era was defined by social reform, and education was no exception. Many philosophies covered earlier in this module were established in the Progressive Era. Changes in education during this period included varying forms of progressivism, the emergence of critical theory, extending schooling beyond the primary level, and the development of teacher unions.

Differing Approaches to Progressivism

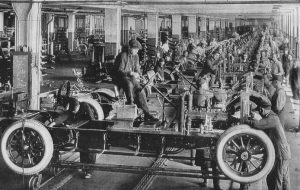

During the Progressive Era’s focus on social reform, different approaches emerged. One group was called administrative progressives, who wanted education to be as efficient as possible to meet the demands of industrialization and the economy. Efficiency involved centralizing neighborhood schools into larger urban systems, allowing more students to be educated for less money. Graded classes, specialized and differentiated subject areas, ringing bells, an orderly daily itinerary, and hierarchical management–with men serving as school board members, superintendents, and principals, and women at the bottom of the rung as teachers–also increased educational efficiency. Educational efficiency required preparing good workers for a rapidly changing economy. Administrative progressives adopted factory models in schools to become better at processing and testing the masses, a continued form of educational assimilation.

Curricular or pedagogical progressives were focused on changes in how and what students were learning. Many progressives saw schooling as a vehicle for social justice instead of assimilation. John Dewey is often called America’s philosopher and the father of educational progressivism. In Democracy and Education, Dewey (1944) theorized two types of learning: “conservative,” which reproduces the status quo through cultural transmission and socialization, and “progressive,” which frames education more organically to experience “growth” and broaden “potentialities” (p. 41). In this case, “progressive” learning has no predetermined outcome and is constantly evolving or progressing. Democratic education, Dewey believed, must build on the existing culture or status quo and free students and adults alike toward conscious positive change based on newly-discovered information, improvements in science, and democratic input from all members of the community, which added legitimacy to a society’s growth.

Dewey and his like-minded progressives have often been referred to as social reconstructionists. They believed education could improve society. Dewey recognized “the ability of the schools to teach independent thinking and to the ability of students to analyze social problems” (Kliebard, 1995, p. 170). Dewey did not expect the school to upend society; rather, as institutions that reached virtually all youth, he saw schooling as the most effective means of developing the habits of critical thinking, cooperative learning, and problem-solving so that students could, once they became adults, carry on this same activity democratically in their attempts to improve society. Their attempts were often met with contempt because such critique threatened the existing socio-political system, which conservative individuals wished to preserve.

Emergence of Critical Theory

In 1923, critical theory was developed in Germany at The Frankfurt Institute of Social Research. With roots in German Idealism, critical theorists sought to interpret and transform society by challenging the assumption that social, economic, and political institutions developed naturally and objectively. In addition, critical theorists rejected the existence of absolute truths. Instead of blind acceptance of knowledge, critical theorists encouraged questioning of widely accepted answers. They challenged objectivity and neutrality, noting that these constructs avoid addressing inequality in political and economic power, social arrangements, institutional forms of discrimination, and other areas. The original Frankfurt School theorists were dedicated to ideology critique and the long-term goal of reconstructing society to “ensure a true, free, and just life” emancipated from “authoritarian and bureaucratic politics” (Held, 1980, p. 15).

A decade later, amidst the Great Depression, America witnessed the emergence of its own Frankfurt School. In the United States, critical theory was aligned with social reconstructionism and situated in social foundations programs in various academic institutions, including its first department in Columbia University’s Teachers College. Why would this movement find its home in American education? Educators were “a positive creative force in American society” that could serve as “a mighty instrument of…collective action” (Counts, 2011, p. 21). Critique, reflection, and action, often referred to as praxis, are intrinsically educational, and these actions transcend the mere transmission of knowledge and culture. America’s social reconstructionists attempted to cultivate a specialized field that drew from many academic disciplines to develop professional teachers’ understanding of how schooling tended to reinforce, evangelize, or perpetuate a given social order. They repudiated a predetermined “blueprint” for training teachers, rejecting “the notion that educators, like factory hands, merely…follow blueprints” (Coe, 1935, p. 26).

When education stops reproducing the status quo, when we self-reflect and become self-critical, when we attempt to produce change and social improvement, when the work of powerful and vested interests is challenged by new knowledge, this is when intellectuals and education become threatening. What developed and continues to be a center of conflict today over the issue of education is a struggle over two polarizing purposes of formal schooling. The first purpose is generally described as the transmission and indoctrination of the values, customs, ideologies, beliefs, and rituals, often controlled by and aligned with more robust social groups. The second purpose of education, often perceived as more radical, is the view that education should serve as a means of critique and social reconstruction to improve society.

Extending Schooling Beyond the Primary Level

While high schools existed in New England towns since the establishment of the Boston Latin Grammar School in 1636, it was not until the early nineteenth century that high schools started appearing in urban areas, and they were not commonly attended until the early twentieth century. While common elementary schooling focused on teaching students morality, a differentiated curriculum in the early twentieth-century high schools “reflected a new, largely economic, purpose for education” (Urban & Wagoner, 2009, p. 234). Debates arose around the high school curriculum: should it teach a classical curriculum or focus on vocational training to meet the needs of the rapidly changing economy in the U.S.? In 1918, the National Education Association published a report called “The Cardinal Principles of Secondary Education” to establish the goals of high school education, including “health, command of fundamental processes, worthy home membership, vocation, citizenship, worthy use of leisure, and ethical character” to prepare students “for their adult lives” by “fitting [them] into appropriate social and vocational roles” (Urban & Wagoner, 2009, p. 271-272). The functionalistic nature of high school also resulted in the development of extracurricular programs including, but not limited to, “athletics,” school “newspapers, and school clubs of various kinds” to teach “students the importance of cooperation” and to “serve…the needs of industrial society” (Urban & Wagoner, 2009, p. 272-276). This resulted in high school becoming a primary institutional mechanism in developing the future teenager.

Changes beyond high school also occurred in the Progressive Era. During this period, the educational ladder expanded to include a system of elementary and high schools and junior high schools, community colleges, and kindergartens, which had served as separate private institutions since the mid-nineteenth century. Not only were more children attending school at this time, but they also attended for more extended periods. Moreover, patriotism, the abolishment of German language instruction in many schools, and intelligence testing were introduced to education following World War I.

The Development of Teacher Unions

While teaching offered career opportunities for women at the time, their increasing presence in the profession was met with little pay and much exploitation. Female teachers were expected to teach more students, particularly in urban areas where immigration tended to ebb and flow. It was not unusual for teachers to forego their salaries during economic downturns, and they had little or no benefits or rights to due process. Male administrators and policymakers typically justified their ill-treatment of teachers by treating them as martyrs for their communities (Goldstein, 2014).

Deeper Dive

Deeper Dive

Professional Organizations for Teachers

Below is a list of professional organizations comprised of teachers and educators. These organizations each have their own guiding values and principles that help to progress the teaching profession.

The National Education Association was established in 1857, initially to address the interests of school administrators. Today, it serves as a major interest group for the teaching profession lobbying at all levels of government. The American Federation of Teachers emerged in 1916 as an outgrowth of teacher associations in Chicago. This group joined with organized labor unions, such as the AFL-CIO (The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations), to increase its formative power. Both organizations continue to exist today with state and local chapters.

Knowledge Check

Knowledge Check

Historical Foundations: Progressive Era to World War II

References

Coe, G. A. (1935). “Blue prints” for teachers? The Social Frontier, 1(7), 26-27.

Counts, G. S. (2011). Orientation. In E. F. Provenzo, Jr., (Ed.)., The social frontier: A critical reader, pp. 19-25. Peter Lang.

Dewey, J. (1944). Democracy and education. The Free Press.

Goldstein, D. (2014) The teacher wars: A history of America’s most embattled profession. New York: Doubleday.

Held, D. (1980). Introduction to critical theory: Horkheimer to Habermas. University of California Press.

Kliebard, H. M. (1995). The struggle for the American curriculum, 1893-1958 (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Urban, W. J., & Wagoner, J. L. (2009). American education: A history (4th ed.). Routledge.

- The following chapter is revised from Foundations of American Education: A Critical Lens (Chapter 3) by Melissa Wells and Courtney Clayton, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License ↵