Module 6: Motivation and Engagement

Module 6 Outcomes

Module 6 Outcomes

- MLO 6.1: Recognize the different motivation theories that can be used to engage students (CLO VII, InTASC 2n, 3i, 5d)

- MLO 6.2: Identify the different motivation theories and factors that encourage students to be engaged. (CLO VII, InTASC 1e)

- MLO 6.3: Differentiate between the strategies that can be used to foster student engagement in various learning contexts. (CLO VII, InTASC 2g, 5b)

Introduction

Motivation[1]

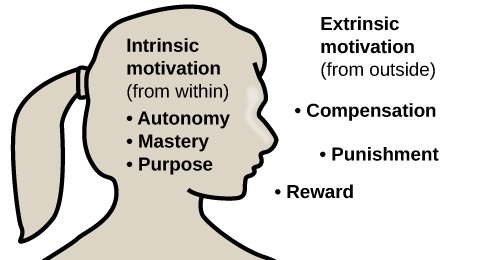

Why do we do the things we do? What motivations underlie our behaviors? Motivation describes the wants or needs that direct behavior toward a goal. In addition to biological motives, motivations can be intrinsic (arising from internal factors) or extrinsic (arising from external factors) (Figure 1). Intrinsically motivated behaviors are performed because of the sense of personal satisfaction that they bring, while extrinsically motivated behaviors are performed in order to receive something from others.

Think about why you are currently in college. Are you here because you enjoy learning and want to pursue an education to make yourself a more well-rounded individual? If so, then you are intrinsically motivated. However, if you are here because you want to get a college degree to make yourself more marketable for a high-paying career or to satisfy the demands of your parents, then your motivation is more extrinsic in nature.

In reality, our motivations are often a mix of both intrinsic and extrinsic factors, but the nature of the mix of these factors might change over time (often in ways that seem counter-intuitive). There is an old adage: “Choose a job that you love, and you will never have to work a day in your life,” meaning that if you enjoy your occupation, work doesn’t seem like . . . well, work. Some research suggests that this isn’t necessarily the case (Daniel & Esser, 1980; Deci, 1972; Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 1999). According to this research, receiving some sort of extrinsic reinforcement (i.e., getting paid) for engaging in behaviors that we enjoy leads to those behaviors being thought of as work no longer providing that same enjoyment. As a result, we might spend less time engaging in these reclassified behaviors in the absence of any extrinsic reinforcement. For example, Odessa loves baking, so in her free time, she bakes for fun. Oftentimes, after stocking shelves at her grocery store job, she whips up pastries in the evenings because she enjoys baking. When a coworker in the store’s bakery department leaves his job, Odessa applies for his position and gets transferred to the bakery department. Although she enjoys what she does in her new job, after a few months, she no longer has much desire to concoct tasty treats in her free time. Baking has become work in a way that changes her motivation to do it (Figure 2). What Odessa has experienced is called the overjustification effect—intrinsic motivation is diminished when extrinsic motivation is given. This can lead to extinguishing the intrinsic motivation and creating a dependence on extrinsic rewards for continued performance (Deci et al., 1999).

Other studies suggest that intrinsic motivation may not be so vulnerable to the effects of extrinsic reinforcements, and in fact, reinforcements such as verbal praise might actually increase intrinsic motivation (Arnold, 1976; Cameron & Pierce, 1994). In that case, Odessa’s motivation to bake in her free time might remain high if, for example, customers regularly compliment her baking or cake decorating skills.

These apparent discrepancies in the researchers’ findings may be understood by considering several factors. For one, physical reinforcement (such as money) and verbal reinforcement (such as praise) may affect an individual in very different ways. In fact, tangible rewards (i.e., money) tend to have more negative effects on intrinsic motivation than do intangible rewards (i.e., praise). Furthermore, the expectation of the extrinsic motivator by an individual is crucial: If the person expects to receive an extrinsic reward, then intrinsic motivation for the task tends to be reduced. If, however, there is no such expectation, and the extrinsic motivation is presented as a surprise, then intrinsic motivation for the task tends to persist (Deci et al., 1999).

In addition, culture may influence motivation. For example, in collectivistic cultures, it is common to do things for your family members because the emphasis is on the group and what is best for the entire group, rather than what is best for any one individual (Nisbett, Peng, Choi, & Norenzayan, 2001). This focus on others provides a broader perspective that takes into account both situational and cultural influences on behavior; thus, a more nuanced explanation of the causes of others’ behavior becomes more likely.

Practice

Practice

Motivation and Engagement

The visual below depicts motivation and engagement factors that influence learning. Click on the motivation and engagement factors that have affected you as a learner and consider ways that you might improve these things.

In educational settings, students are more likely to experience intrinsic motivation to learn when they feel a sense of belonging and respect in the classroom. This internalization can be enhanced if the evaluative aspects of the classroom are de-emphasized and if students feel that they exercise some control over the learning environment. Furthermore, providing students with activities that are challenging, yet doable, along with a rationale for engaging in various learning activities can enhance intrinsic motivation for those tasks (Niemiec & Ryan, 2009). Consider Hakim, a first-year law student with two courses this semester: Family Law and Criminal Law. The Family Law professor has a rather intimidating classroom: He likes to put students on the spot with tough questions, which often leaves students feeling belittled or embarrassed. Grades are based exclusively on quizzes and exams, and the instructor posts results of each test on the classroom door. In contrast, the Criminal Law professor facilitates classroom discussions and respectful debates in small groups. The majority of the course grade is not exam-based, but centers on a student-designed research project on a crime issue of the student’s choice. Research suggests that Hakim will be less intrinsically motivated in his Family Law course, where students are intimidated in the classroom setting, and there is an emphasis on teacher-driven evaluations. Hakim is likely to experience a higher level of intrinsic motivation in his Criminal Law course, where the class setting encourages inclusive collaboration and a respect for ideas, and where students have more influence over their learning activities.

In this module, we will work to understand the relationship between motivation and engagement and how to design learning experiences using strategies for engagement. Engagement is having a connection to emotions or feelings, such as a sense of belonging, purpose, or commitment. Motivation is connected to the energy to act or do or the willpower or drive to do something.

Reflect

Reflect

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation

Intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation are two types of motivation that drive people to do what they do. Watch the video below and reflect on how intrinsic and extrinsic motivation have shown up in your own experience.

- The following chapter is revised from Introduction to Psychology by Lumen Learning, under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ↵

Identify evidence-based practices for enhancing student motivation in learning.

Disposition. The teacher makes learners feel valued and helps them learn to value each other.

Knowledge. The teacher understands the relationship between motivation and engagement and knows how to design learning experiences using strategies that build learner self-direction and ownership of learning.

Performance. The teacher engages learners in questioning and challenging assumptions and approaches in order to foster innovation and problem solving in local and global contexts.

Knowledge. The teacher understands that each learner’s cognitive, linguistic, social, emotional, and physical development influences learning and knows how to make instructional decisions that build on learners’ strengths and needs.

Knowledge. The teacher understands and identifies differences in approaches to learning and performance and knows how to design instruction that uses each learner’s strengths to promote growth.

Performance. The teacher engages learners in applying content knowledge to real world problems through the lens of interdisciplinary themes (e.g., financial literacy, environmental literacy).