K12 School Models and Funding

Preparing to Learn

Preparing to Learn

K12 School Models and Funding

Before discussing school funding and its impact on learning opportunities, complete the assessment below to check what you already know, what you need to unlearn, and what you might be interested in exploring further.

Before exploring different school models, consider your K12 educational experiences. What types of schools did you attend? What types of schools were available in your community?

Throughout America, states have compulsory education laws, yet none have laws that dictate what type of school children and teens must attend. While not specifically addressed by the constitution, the education of children is based on the premise that all students deserve an education. This supposition includes the beliefs that an education should not be denied based on socioeconomic status, geographic location, first language, or race/ethnicity.

Types of Schools[1]

The two major broad categories of schools in the United States are public and private. Public schools are funded by public tax dollars to educate children in that community at no cost for attendance to the students and their families. While some states allow for open enrollment, where children can request to attend public schools located outside of the district in which they live, typically, the governance of public schools provides free education to all students who live within the district’s boundary. Private schools are operated by private funds and are maintained by groups and organizations without affiliation with the government. Typically, the funding for operating private schools is supported by charging tuition to students and families. Unlike public schools, private schools may be organized around a certain position, belief system, or structure. Depending on where families live, students may choose where to attend school. Both public and private schools offer various options or models of instructing students.

There are a variety of public school models, including traditional, charter, magnet, Montessori, virtual, alternative, and language immersion. Private school models include traditional, religious, parochial, Montessori, Waldorf, virtual, boarding, and international schools. Some school models may be public or private. The table below includes a breakdown of school models, their funding source, and key characteristics.

Table: School Models by Funding, Enrollment, and Key Characteristics

| School Model | Public or Private | Enrollment | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Public | Public | Open/School Boundary Lines | State and local governance, policy, and curriculum. |

| Magnet | Public | Open across school district/Application or lottery | It specializes in programs (art, science, math, etc.) and promotes diversity across a district. |

| Alternative | Public | Students that cannot attend traditional school due to a variety of factors. | State and local governance, policy, and curriculum. Small class sizes and alternative scheduling. Individualized support. |

| Language Immersion/ Bilingual | Both | Open across school district/Application | A portion of instruction is taught in a language other than English. Students are immersed in a second language for part of instruction. |

| Charter | Both | Open across school district/Application | Autonomous from local and state authority as long as the school meets the charter mission and performance measures. |

| Montessori | Both | Open across school district/Application | The philosophy is that children need a connection to the environment. Focuses on real-life experiences. Montessori schools are student-led and focused on developing independence through real-life activities. |

| Waldorf | Private | Application/Tuition | Believes each child has a unique potential that should be developed through education to better humanity. While not specifically religious, Waldorf schools are based on general spirituality. Focuses on imagination and fantasy. Students in younger grades are not exposed to technology, and in older grades, technology is only used as a tool for learning. |

| Virtual | Both | Open across school district/Application | The majority of instruction is provided in an online environment. |

| Traditional Private | Private | Application/Tuition | The curriculum is decided upon by the governing body (board, organization, or company). It may be non-profit or for-profit. |

| Religious | Private | Application/Tuition | The mission is to teach religious values and the core curriculum. |

| Parochial | Private | Application/Tuition | The mission is to teach religious values in addition to teaching the core curriculum. School is sponsored by a local church through funding. |

| Boarding | Private | Application/Tuition | Community of scholars, artists, and athletes. The school provides food and housing. |

| International | Private | Application/Tuition | Follows a curriculum different from that of the country where the school is physically located. May use the International Baccalaureate curriculum, among others. Students consist of a diverse population that is often highly mobile. |

| Department of Defense Education Activity (DoDEA) | Public | Serves military and Department of Defense dependents serving overseas and in the U.S. U.S. contractor dependents may attend for a fee. | Follows a standard curriculum across schools. It is the 10th largest school district in the U.S. It Consists of two parallel districts: Department of Defense Dependents Schools (DoDDS) operating in Europe and the Pacific, and Department of Defense Domestic Dependent Elementary and Secondary Schools operating in the Americas. |

Two other schooling options not listed in the table are homeschooling and Bureau of Indian Education schools. Homeschool is a school choice option where students are educated at home by a parent or caregiver. Each state has laws governing how homeschools operate and reporting of progress. In the state of Minnesota, parents have the option of creating private schools in their home for the purpose of teaching their children (MDE, 2023). Although typically homeschools do not receive public funding, in Minnesota, families can apply annually for Nonpublic Pupil Aid funds to defray some costs of educating children. States typically

Bureau of Indian Education schools (also referred to as reservation schools are open to members of federally recognized tribal nations. The troubled history of these schools is not reflective of the schools’ purpose today.

Starting in the early 1800s at the start of Indian territorial and up until the 1970s, the federal government created Indian boarding schools across the nation. American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children were forcibly removed from their families, tribal nations, native villages, and communities with the purpose of assimilating children to Western customs. During this historic period, the federal government operated 408 Indian boarding schools in 37 states or then territories, including Alaska and Hawaii. At the residential schools, children were not allowed to speak their native languages, nor could they engage in their traditional spiritual or cultural beliefs. The conditions at the schools were deplorable, with children experiencing physical, emotional, spiritual, and sexual abuse. In many cases, the children died while in the residential schools, and after an investigation beginning in 2021, over fifty of the previous schools in the United States were found to have burial sites (U.S. Department of Interior, 2021).

Critical Perspective

Critical Perspective

The Impacts of Indian Residential Boarding Schools

With the news of the discovery of mass burial sites at Indian residential schools in Canada, immediate questions arose about the practice at schools in the United States. The atrocities of the cultural genocide at these schools continue to have lingering impacts on American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian communities.

The resources below explore the lingering impacts:

With the passage of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 (ISDEAA), the role of the Bureau of Indian Education changed. Off-reservation boarding schools were no longer institutions of assimilation but rather schools to respect, honor, and support tribal sovereignty and self-determination. Today, BIE schools provide culturally relevant education to equip students with skills to help them grow into successful members and leaders of their sovereign nations. Currently, the Bureau of Indian Education programming teaches 46,000 students in 183 schools. The BIE also oversees four off-reservation boarding schools in Oklahoma, California, Oregon, and South Dakota, and tribal nations directly operate boarding schools on sovereign lands within Oklahoma, South Dakota, and North Dakota (U.S. Department of Interior, 2019).

School Funding

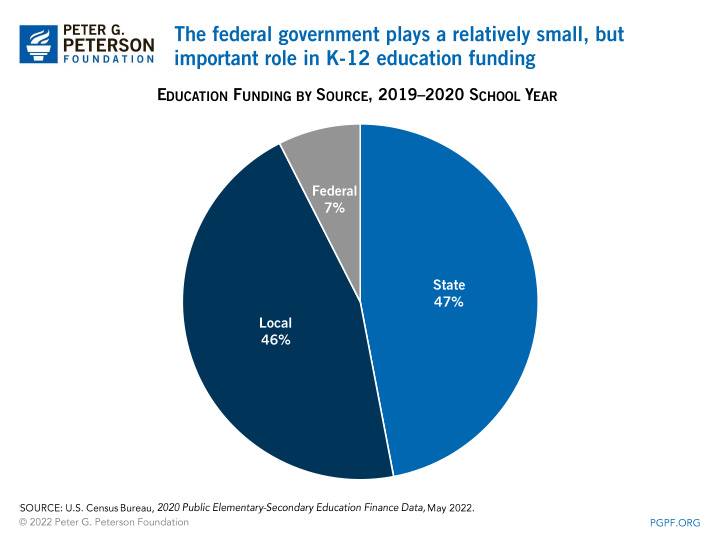

As an educator, it is important to have a basic understanding of how schools are funded. Public schools, for instance, receive funds through a hierarchy of allocations, such as school governance models, with the federal, state, and local governments having different funding structures and distributions. The total amount spent on public K-12 education in 2019-2020 from these funding sources totaled $771 billion (The Peter G. Peterson Foundation, 2022).

Deeper Dive

Deeper Dive

Understanding the Funding of Public Education

A Need for Improvement[2]

As you orient yourself to the existing structures for funding education in the U.S., be aware that these current structures aren’t perfect. The organization EdBuild researched challenges with existing school funding systems in the U.S. Their research explains how the existing funding system is broken[2], some ideas for fixing it[3], and provides other tools to learn more[4].

Federal Funding

Currently, the federal government provides seven percent of a school’s budget, which in 2020 amounted to $58 billion in federal funding (The Peter G. Peterson Foundation, 2022). Federal funds for education are proposed by the president and set by Congress through budget resolutions. Still, the amount of funding is primarily determined by who holds office at the time of the resolution. The Department of Education is not the only provider of funds for schools, as funds come from other agencies such as the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which provide early child programming through Head Start. The Department of Agriculture contributes revenue for free and reduced lunch programs.

In adherence to the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), most federal funds are connected directly to targeted assistance programs that strive to reduce the spending gap for at-risk students. One of the most extensive programs that uses federal funding is Title I, which provides revenue for districts with high numbers or percentages of low-income families to help students meet academic standards. Other targeted programs for federal revenue include ones for multilingual learners, students with special needs through the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, literacy programs, and teacher professional development and improvement.

State and Local Funding

With less than ten percent of school funding coming from the federal government, state and local governments contribute the most significant portion of the cost to fund education. Like the federal targeted assistance program dollars, states also endeavor to provide equitable funding to schools and districts.

Determining how much state dollars are appropriated for schools and education is a complex process involving funding formulas that are calculated based on state tax dollars.

Funding Formulas

| Formula Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Student-based | Formula determines the cost of education for the average student and multiplies that number by district enrollment. Multipliers may adjust for the extra cost for students needing more assistance or based on certain programs. |

| Resource-based | Formula determines the cost of delivering education and is based on the cost of resources such as curricular materials and teacher and staff pay. Multipliers may adjust for the extra cost for students needing more assistance or based on certain programs. |

| Program-based | Formula determines the cost of education based on specific programs or initiatives. Typically, this formula does not add multipliers for other resources or student categories. |

| Hybrid | State uses one or more formulas for calculating state allocations of school funds. |

To determine your state’s education funding formula, visit the EdBuild: FundED National Policy Map. Knowing your state’s funding formula and how state tax dollars are used for school funding better prepares you to understand how schools in your area are funded. This knowledge also helps you to be a more informed voter when school funding initiatives are on the ballot for elections.

After dollars are received from the federal government and SEA, Local Education Agencies disperse funds to school districts. States provide as much as forty-eight percent of the funds for each school, and funds from local citizens, generally from levies on property taxes, can provide as much as forty-four percent (Chen, 2022). Collectively, the funds each school receives are distributed by school district decision-makers. Most are disseminated by the cost of teachers, staff, and administrators and by the cost of equipment and school building maintenance. Additionally, per pupil cost is based on the resources needed to educate that student.

A new approach for local funding has developed whereby the process is streamlined to utilize a weighted student funding formula to appropriate resources based on student needs. This relatively new process is based on reform efforts, which advocates believe could lead to more equitable funding of local schools as the formula would transparently reflect actual expenditures for each school and could potentially promote equity by connecting resources with the specific needs of students (Skinner, 2019).

Systemic Issues with School Funding

Even with reforms being considered, the lack of national calculation for school funding coupled with each state having its formula creates disparities in the funding between schools. This gap is further exacerbated at the local funding level, where property taxes are the primary source of subsidizing the cost of education. Economically disadvantaged neighborhoods and communities cannot provide the same tax revenue as wealthy ones.

The Every Student Succeeds Act aimed to close achievement gaps, reduce inequity, and increase academic performance for all students through improved quality instruction. Yet these goals are challenging to achieve when systemic inequality, such as the geographical location of disadvantaged families compared to financially privileged communities, further exacerbates school funding. The stark reality is, when comparing schools based on similar numbers of students served, school districts serving primarily students of color receive $23 billion less funding than schools serving mostly white students.

Another inequity that influences school funding by geographic location would be population density. Forty-six million Americans, or roughly fourteen percent of the population, reside in rural communities (Dobis et al., 2022). Fewer citizens mean fewer homes within a local community upon which to create property tax revenue for schools. The intersection of rurality and poverty creates barriers to many quality-of-life measures, including access to healthcare, affordable nutrition, broadband internet, and quality educational services. Historically, the rate of nonmetro (or rural) poverty compared to metro (or urban) poverty has been higher since poverty rates were first officially recorded in the 1960s (Farrigan, 2022).

In Minnesota (where the authors of this text reside), rurality has a similar impact as wealthy versus disadvantaged communities. According to the Minnesota Rural Education Association’s Rural Kids Count Report: Addressing Rural School Equity, rural schools of all sizes in the state lag behind urban ones in per-student funding. The dichotomy in education allotted funds between the rural and urban/urban adjacent schools resulted in nearly $1400 less per pupil.

When exploring rural poverty, another systemic issue is the historic relocation of Indigenous people to rural tracts of land under the Indian reservation system. As white settlers took the land that rightfully belonged to the Native peoples, the United States government forced Indigenous peoples onto reservations with devastatingly tragic results and generational impacts. In Minnesota and two of its border states, North and South Dakota, the most impoverished counties are those where reservations are located. The juxtaposition of systemic racism, geographic location, and poverty results in school funding barriers.

Conclusion

Knowledge Check

Knowledge Check

K-12 School Models

References

Civil Rights Litigation Clearinghouse. (2016). Case: Gary B. v. Snyder.

Dobis, E.A., Krumel, T.P. Jr., Cromartie, J., Conley, K.L., Sanders, A., & Ortiz, R. (2021). Rural America at a Glance.

Edbuild. (2023). FundED: National policy maps.

Edbuild. (2023.) 23 billion. https://edbuild.org/content/23-billion#US

Education Commission of the United States. (2023). Education governance dashboard.

Evans, A. (2020). The other branch: Outcomes of Gary B. v. Snyder

Farrigan, T. (2022). Rural poverty and well-being.

Governor Gretchen Whitmer. (2020). Governor Whitmer and plaintiffs announce settlement in landmark Gary B. literacy case.

Minnesota Department of Education (MDEa). (2023). Home school education.

Minnesota Department of Education (MDEb). (2023). Nonpublic.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2017). State education practices.

Nolan, F. (2017). Rural kids count report: Addressing rural school equity.

Peter G. Peterson Foundation. (2022). How is K-12 education funded?

Ramirez, L. (2019, July). The dilemma with public school funding. [Video]. TED conferences. Lizeth Ramirez: The dilemma of public school funding

Skinner, R.R. (2019). State and local financing of public schools. [PDF]

United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2022). Elementary, middle and high school principals.

United States Congress. (2023). Fourteenth Amendment equal protection and other rights.

United States Department of Education. (2023). Every Student Succeeds Act.

United States Department of Education. (2023). About ED. https://www2.ed.gov/about/landing.jhtml

United States Department of Interior. (2019). Indian boarding schools.

United States Department of Interior. (2021). Federal Indian boarding school initiative.

- The following section is revised from Foundations of American Education: A Critical Lens (Chapter 4) by Melissa Wells and Courtney Clayton, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License ↵

- The following section is revised from Foundations of American Education: A Critical Lens (Chapter 4) by Melissa Wells and Courtney Clayton, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License ↵