Historical Foundations: Colonial America to the Progressive Era

Preparing to Learn

Preparing to Learn

Historical Foundations: Colonial America to the Progressive Era

Before discussing the historical foundations of education, complete the assessment below to check what you already know, what you need to unlearn, and what you might be interested in exploring further.

Historical Foundations

Introduction[1]

Now that we understand the origin and essence of educational philosophies, let’s review the historical foundations of education in the United States. Education, as we know it today, has a long history intertwined with the development of the United States. There are moments in history where only specific populations could benefit from education, but over time, education became more equitable and expanded to include everyone. In this section, we will follow historical events through key periods of U.S. history to see the forces that left lasting influences on educational equity in the United States.

Colonial America

Public education has undergone much change since its origin in Colonial America. In Colonial America, in the First Charter of Virginia in 1606, King James I set forth a religious mission for investors and colonizers to disseminate the “Christian religion” among the Indigenous population. His colonial and educational mission would impact settlement and education in America for centuries. The following section will explore how education started evolving in Puritan Massachusetts and the Middle and Southern Colonies during the colonial period.

Puritan Massachusetts

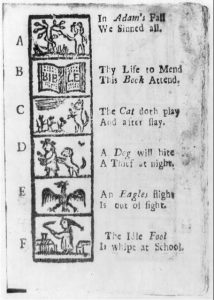

Puritans in Massachusetts believed educating children in religion and rules from a young age would increase their chances of survival or, if they did die, increase their chances of religious salvation. Puritans in Massachusetts established the first compulsory education law in the New World through the Act of 1642, which required parents and apprenticeship masters to educate their children and apprentices in the principles of Puritan religion and the laws of the Commonwealth. The Law of 1647, also called the Old Deluder Satan Act, required towns of fifty or more families to hire a schoolmaster to teach children basic literacy. Because of similar religious beliefs and the physical proximity of families’ residences, formal schooling developed quickly in the commonwealth of Massachusetts. Connecticut, New York, and Pennsylvania followed in Massachusetts’ footsteps, passing similar laws and ordinances between the mid- and late-seventeenth century (Cremin, 1972).

During this time, children learned to read at home using the Holy Scriptures and catechisms (small books that summarized key religious principles) as educational texts. The primers “contained simple verses, songs, and stories designed to teach at once the skills of literacy and the virtues of Christian living” (McClellan, 1999, p. 3).

The importance of faith, prayer, humility, rewards of virtue, honesty, obedience, thrift, proverbs, religious stories, the fear of death, and hard work served as major moral principles featured throughout the texts. When Indigenous people were depicted or mentioned in texts, they were portrayed as needing salvation through English cultural norms.

At this time, dame schools were another form of education. Where available, some parents sent their children to a neighboring housewife who taught them basic literacy skills, including reading, numbers, and writing. Because families paid for their children to attend dame schools, this education was mainly available to middle-class families. Teaching aids and texts included scripture, hornbooks, catechisms, and primers (Urban & Wagoner, 2009).

More expensive than dame schools, Latin grammar schools were another type of education available to students at this time. The first Latin grammar school was established in Boston in 1635 to teach boys subjects like classical literature, reading, writing, and math at what we would consider the high school level today in preparation for attending Harvard (Powell, 2019).

The Middle and Southern Colonies

In Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia, town or village schooling was not as common. The populations in these states were sparser, and they focused more on economic opportunities for survival than religion. Education was considered a private matter and a responsibility of individual parents, not the government. Schooling was seen as a service that should be paid for by the users, creating a stratified system of education where wealthy families had access to schooling and others did not. Wealthier parents often sent their children to English boarding schools or paid for private schooling in the colonies. Wealthy families also sent their children to parson schools, operated by a highly educated minister who opened his home to young scholars and often taught secular subjects. Education for the poor was usually limited to the rudiments of basic literacy learned at home or occasionally at church.

Occasionally, charity schools, often referred to as “endowed ‘free’ schools” (Urban & Wagoner, 2009), were established when an affluent individual made provisions in his or her will, including land, to construct and manage a school for the poor. In addition, field schools were occasionally built in rural areas. Named after the abandoned fields in which they were built, these schoolhouses offered affordable education to students. A teacher’s salary came from fees students’ families paid, and teachers often boarded with a local family while serving a field school. These schools were also called rate schools, subscription schools, fee schools, and eventually district schools (Urban & Wagoner, 2009).

As evidenced above, education in Colonial America, specifically in the mid-Atlantic and southern colonies, was heavily stratified and remained out of reach for most inhabitants. New England Puritans worked hard to establish schools. Fear, anxiety, and struggle for survival lent urgency to their quest for cultural transmission, which helps us understand their desire for formal schooling.

| Types of Schooling in New England | Types of Schooling in the Middle and Southern Colonies |

|---|---|

|

|

Reflect

Reflect

Separation of Church at State?

Even though today’s public schools operate separately from religion, the first schools in the U.S. had strong ties to religion. Where do you see those roots still in action today, even implicitly?

American Revolutionary Era

Public education shifted after the American Revolution as the United States was working to establish its systems and identity. Many key founders believed that public education was a prerequisite in a republic. Three groups had distinct post-revolutionary plans for education and schooling, all intended to serve as part of the founding process: Federalists, Anti-Federalists, and the lesser-known Democratic-Republican Societies.

Federalists

Alexander Hamilton, George Washington, and John Adams, among other Federalists, focused on building a new nation and national identity by following the new Constitution, which consolidated power in a new federal government. Federalists supported mass schooling for nationalistic purposes, such as preserving order, morality, and a nationalistic character, but opposed tax-supported schooling, viewing it as unnecessary in a society where elites rule.

Noah Webster was one of the great advocates for mass schooling, and the purposes for which he supported schooling included teaching children not just “the usual branches of learning,” but also “submission to superiors and to laws [and] moral or social duties.” Smoothing out frontier folk’s “rough manners” was very important to Webster. Furthermore, Webster placed great responsibility among “women in forming the dispositions of youth” to “control…the manners of a nation” and that which “is useful” to an orderly republic (Webster, 1965, 67, 69-77). Webster’s treatise on education and his spellers (like his 1783 American Spelling Book) were intended to develop a literate and nationalistic character to shape useful, virtuous, and law-abiding citizens with attachments to Federalist America.

Anti-Federalists

Contrary to Federalists, Anti-Federalists opposed a strong central government; instead, they preferred state and local forms of government. The Anti-Federalists believed that the success of a republican government depended on small geographical areas, spaces small enough for individuals to know one another and to deliberate collectively on matters of public concern. This is because Anti-Federalists feared concentrated power.

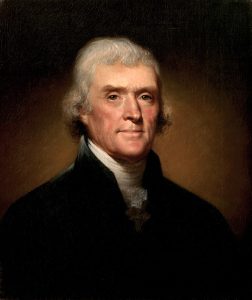

Thomas Jefferson was an Anti-Federalist. An aristocrat whose genteel lifestyle was bolstered by his violent oppression of enslaved people, Jefferson put forth proposals to educate all white citizens in the state of Virginia. Jefferson proposed a system of tiered schooling that included primary schools, grammar schools, and the College of William and Mary. The foundation of his tiered schooling plan included three years of tax-supported schooling for all white children, with limited options for a few poor children to advance at public expense to higher levels of education. While he suggested limited educational opportunities for women, no other key founder advocated giving high-achieving scholars from poor families a free education. Religion was not a core curricular area in primary and grammar schools. However, his plans were viewed as too radical by his aristocratic peers, and they correspondingly rejected his state education proposals.

Democratic-Republican Societies

The third group of post-revolution political activists formed several clubs broadly described as the Democratic-Republican Societies during the 1790s. Members of these political clubs included artisans, teachers, shipbuilders, innkeepers, and working-class individuals. They generally supported universal, government-funded schooling, not simply to secure allegiance and order but also to develop democratic citizen virtue and venues for deliberative learning and opportunities for dissent. The Democratic-Republican Societies viewed education as a means to prepare active citizens for new civic roles, and they considered the government responsible for providing positive benefits to individuals to realize more fulfilling citizenship through venues such as education.

Reflect

Reflect

How Today's Educational System Was Informed by History

Where do we see elements of ideologies represented in Federalist, Anti-Federalist, and Democratic-Republican in today’s schools? What has remained the same, and what has changed? Which perspective do you see as the most valuable in today’s public schools?

Early National Era

During the early- to mid-nineteenth century, the United States was expanding westward, and urbanization and immigration intensified. This period of history was defined by the emergence of the common school movement and normal schools, though conflicts over the organization and control of education continued. This period also saw the advent of higher education.

The Common School Movement

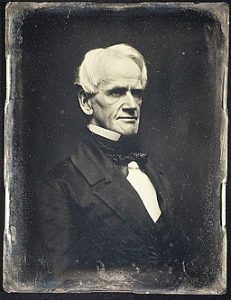

Horace Mann established the common school movement and advocated for normal schools to prepare teachers.[/caption]

Common schools were elementary schools where all students–not just wealthy boys–could attend for free. Common schools were radical in their status as tax-supported free schooling, but their conservative-leaning curriculum addressed traditional values and political allegiance. Schooling offered increasing opportunities for families’ children, especially working-class families, by teaching fundamental values, including honesty, punctuality, inner behavioral restraints, obedience to authority, hard work, cleanliness, and respect for law, private property, and representative government (Urban & Wagoner, 2009). Horace Mann, Massachusetts’s first Secretary of Education and Whig (formerly Federalist) politician, was the leader of the common school movement, which began in the New England states and then expanded into New York, Pennsylvania, and then into westward states.

The Development of Normal Schools

With the rise of common schools, Horace Mann pivoted to how female teachers would be educated. For Mann, the answer was to create teacher training institutions originally called normal schools. A French concept dating back to the sixteenth century, école normale was the term used to identify a model or ideal teaching institute. Once adopted in the United States, the institution was called a normal school.

The first normal school in America was established in Lexington, Massachusetts, in 1839 (now Framingham State University). They were primarily used to train primary school teachers, as middle and high schools did not yet exist. The curriculum included academic subjects, classroom management, school governance, and teaching practice. Teacher credentialing began and was regulated by state governments. Moreover, this contributed to the professionalization of teaching, and normal schools eventually became colleges or schools of education. Many normal schools eventually became full-fledged liberal arts and research institutes. Catherine Beecher was the first well-known teacher of the time and one of the first teachers of normal schools.

Because the teaching profession was being feminized, administrators and policymakers viewed this as an opportunity. Men were exiting the profession, and women were typically paid much less, allowing more women to be hired for less money to educate the growing ranks of students as common schools spread westward. Furthermore, once the profession was feminized, teaching became perceived as a missionary calling rather than an academic pursuit. While male policymakers insisted women were better nurturers and more suited to teaching morality and correct behavior in children, framing the discourse of teaching around a calling helped rationalize lower pay for women and fewer advancement possibilities.

Reflect

Reflect

Teaching As A Women's Profession

How do you see the early roots of feminizing the teaching profession still in effect today?

Conflicts in the Common School Movement

The common school movement was not without its conflicts. Whigs (formerly Federalists), including Horace Mann, sought to establish state systems of schooling to create standardization and uniformity in curricula, classroom equipment, school organization, and professional credentialing of teachers across state schools. Democrats, however, often supported public schooling but feared centralized government, thus opposing the centralization of local schools under the common school movement. The battle between Whigs and Democrats during the nineteenth century represents one of the initial conflicts related to public schooling.

Another vital conflict related to the common school movement was the clash between urban Protestants and Catholics. Typically, from Protestant backgrounds, common school reformers continued to use the Bible as a standard text in classrooms without considering the potential conflict this could generate in diverse communities. Horace Mann advocated using only generalized scripture to prevent offending different sects. However, what appeared to Protestants as a generalization of Christian text was very insulting to Catholic immigrants, who were becoming the second largest group of city dwellers at the time. Protestants realized that it was best to reduce the religious content in the common school curriculum, but unhappy Catholic leaders created their own private parochial schools. This conflict generated a greater theoretical acceptance of the separation of church and state doctrine in publicly funded common schools. However, in practice, common schooling continued to infuse Protestant biases for over a century.

Common schools also faced conflict in Southern states, including Jefferson’s Virginia, until after the Civil War. Planters had no interest in disturbing the status quo by educating poor whites or enslaved people. Driven by Southern aristocracy, education continued to be viewed as a private family responsibility and class privilege. In fact, many southern states prohibited educating enslaved people and passed state statutes that attached criminal penalties for doing so.

Enslaved people have often been depicted in American history textbooks as passive toward their owners. This is a misrepresentation of history. African Americans escaped, committed espionage on plantations, negotiated statuses, and occasionally educated themselves behind closed doors. For enslaved people, education and knowledge represented freedom and power. Once emancipated, they continued their relentless quest for learning by constructing their own schools throughout the South, even with minimal resources. Unlike many free whites, African Americans placed an exceptional value on literacy due to generations of bondage.

Critical Perspective

Critical Perspective

Words Matter

You will notice in this module that the term “enslaved person” is used instead of “slave.” Part of critical theory involves questioning existing power structures, even in word choice. Recently, academics and historians have shifted away from using the term “slave” and have begun replacing it with “enslaved person” because it places “humans first, commodities second” (Waldman, 2015, para. 2).

Even while slavery continued throughout the South, segregation continued in the North. One of the first challenges to segregation occurred in Boston, Massachusetts. Benjamin Roberts attempted to enroll his five-year-old daughter, Sarah, in a segregated white school in her neighborhood, but Sarah was refused admission due to her race. Sarah attempted to enroll in a few other schools closer to her home but was again denied admission for the same reason. Mr. Roberts filed a lawsuit in 1849, Sarah Roberts v. City of Boston, claiming that because his daughter had to travel much farther to attend a segregated and substandard black school, Sarah was psychologically damaged. The state courts ruled in favor of the City of Boston in 1850 because state law permitted segregated schooling. This case would be cited in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1898 and in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954

Higher Education in the Colonies and Antebellum America

Colleges throughout the eastern seaboard states and former colonies symbolized elite education. These institutions developed throughout the North, Mid-Atlantic, and Southern states, often subsidized by state legislatures. Religious sects competed to establish colleges in multiple states in hopes of garnering more adherents to their respective sects. Baptists, Catholics, Quakers, Congregationalists, and Presbyterians were among the groups responsible for this competition.

| College | Founders and Year Established |

|---|---|

| New College (Harvard University) | Massachusetts Colonial Legislature (Puritan or Congregational), 1636 |

| College of William & Mary | King William III and Queen Mary II (Church of England), 1693 |

| King William’s School (St. John’s College) | Maryland Colony, Church of England, 1696 |

| Collegiate School (Yale University) | Puritan or Congregational, 1701 |

| Kent County Free School (Washington College) | Non-Sectarian, Maryland, 1723 |

| College of Philadelphia (University of Pennsylvania) | Benjamin Franklin, 1740 |

| Bethlehem Female Seminary (Moravian College) | Moravian Church in Pennsylvania, 1742 |

| Free School (University of Delaware) | Francis Alison, Non-Sectarian, 1743 |

| College of New Jersey (Princeton) | New Light Presbyterians, 1746 |

| Augusta Academy (Washington & Lee College) | Presbyterian, 1749 |

Post Civil War

Following the Civil War, significant restructuring of the United States’s political, economic, social, and educational systems occurred. Schooling continued to be viewed as necessary to maintain stability and unity. During this era, education was shaped by the increasing influence of the federal government, the beginning of education in the South, the Morrill Acts, and Native American boarding schools.

Increasing Influence of the Federal Government

Elazar (1969) asserted that “crisis compels centralization” (p. 51) happens when the nation undergoes a calamity. It eventually leads to the federal government exercising extra-constitutional actions on its own will or as a result of demands made by state and local governments. The post-Civil War Era provides one example of this effect. The U.S. Congress established requirements for the Southern states to reenter the Union. Radical Republicans, as they were called after the Civil War, believed that the lack of common schooling in the South had contributed to the circumstances leading to war, so Congress required Southern states to include provisions for free public schooling in their rewritten constitutions.

Of course, Southern states followed the requirements and drafted language that supported schools, but they created loopholes like separate and segregated schools. Black schools received substantially lower funding than White schools, creating yet another form of institutionalized racism that would have long-lasting consequences for African American communities.

The Beginning of Education in the South

Following the Civil War, nearly four million formerly enslaved people were homeless, without property, and illiterate. In response, Congress created the Freedmen’s Bureau (officially called the U.S. Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands). Supervised by northern military officers, the Freedmen’s Bureau distributed food, clothing, and medical aid to formerly enslaved people and poor Whites and created over 1,000 schools throughout the southern states. The Freedmen’s Bureau effectively lasted only for seven years, but it represented a massive federal effort that provided some benefits.

In addition to Freedmen’s schools, Yankee schoolmarms also headed south as missionaries to help educate formerly enslaved people. They sought mutual benefits: to educate the illiterate and simultaneously secure themselves in the eyes of God. As missionaries, female teachers learned that their work was a calling to instill morality in the nation’s students, and this calling was pursued for the good of mankind instead of financial gain. This same missionary status fueled both the migration of teachers westward following national expansion and the thousands of schoolmarms that migrated to the South to educate formerly enslaved people who, they believed, had to be redeemed through literacy, Christian morality, and republican virtue (Butchart, 2010).

However, African Americans were preemptively educating themselves. Formerly-enslaved people knew the connection between knowledge and freedom. Ignorance was itself oppressive; knowledge, on the other hand, was liberating. Literate African Americans often taught children and adults alike and created their own one-room schoolhouses, even with limited resources. By 1866, in Georgia, African Americans partially financed 96 of 123 evening schools and owned 57 school buildings (Anderson, 1988). The African American educational initiatives caught Northern missionaries off guard:

Many missionaries were astonished, and later chagrined…to discover that many ex-slaves had established their own educational collectives and associations, staffed schools entirely with black teachers, and were unwilling to allow their educational movement to be controlled by the ‘civilized’ Yankees.” (Anderson, 1988, p. 6)

In addition, industrial schools were built in the South for Black Americans. Southern policymakers, northern industrialists, and philanthropic groups partnered to establish industrial schools focused on vocational or trade skills. Southern policymakers benefitted because industrial schools resulted in segregated higher education, which further limited access to equality. Northern industrialists benefited because they gained skilled laborers. Philanthropists believed they were giving Black Americans access to education and jobs.

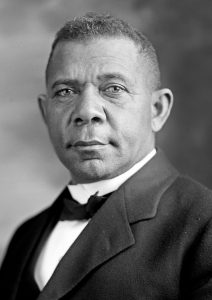

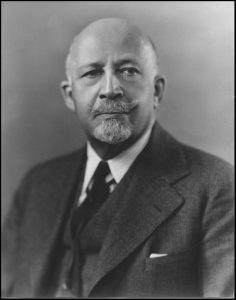

Two African American leaders in the late nineteenth century had different perspectives on newly developed industrial schools. Booker T. Washington was born enslaved in 1856 and grew up in Virginia. He attended the Hampton Institute, whose founder, General Samuel Armstrong, emphasized that “obtaining farms or skilled jobs was far more important to African-Americans emerging from slavery than the rights of citizenship” (Foner, 2012, p. 652-653). Washington supported this view as head of the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. In his famous 1895 “Atlanta Compromise” speech, Washington did not support “ceaseless agitation for full equality”; rather, he suggested, “In all the things that are purely social, we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress” (Foner, 2012, p. 653). Washington feared that if demands for greater equality were imposed, it would result in a white backlash and destroy what little progress had been made.

W.E.B. Du Bois viewed the situation differently. Born free in Great Barrington, Massachusetts in 1868, Du Bois was the first African American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard University. He served as a professor at Atlanta University and helped establish the NAACP in 1905 to seek legal and political equality for African Americans. He opposed Washington’s pragmatic approach, considering it a form of “submission and silence on civil and political rights” (Urban & Wagoner, 2009, p. 176).

The Morrill Acts of 1862 and 1890

In addition to the Freedman’s Bureau, the federal government implemented two legislative acts related to education. The Morrill Act of 1862 gave states 30,000 acres of land for each senator and representative it had in Congress in 1860. The income generated from the sale or lease of this land would provide financial support for at least one agricultural and mechanical (A&M) college, known as a land-grant institution (Urban & Wagoner, 2009). Land-grant institutions were designed to support the growing industrial economy. The second Morrill Act of 1890 required “land-grant institutions seeking increased federal support…to either provide equal access to the existing A&M colleges or establish separate institutions for the ‘people of color’ in their state” (Urban & Wagoner, 2009, p. 188). The Morrill Acts demonstrated how industrialization and westward expansion increased federal government involvement in education policy to meet national needs.

Critical Perspective

Critical Perspective

The "Value" of Education

The opinions of Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois are still prevalent today when considering educational options after high school. Some believe technical schools exist for those who choose not to attend a four-year college. They believe a four-year degree is unnecessary to positively contribute to society. In contrast, others believe that a four-year degree is needed to expand understanding for future, more “professional” careers.

Who is right in these scenarios? What influenced where students choose to learn in post-secondary education? Critiquing the implicit biases we hold regarding others’ educational choices is important.

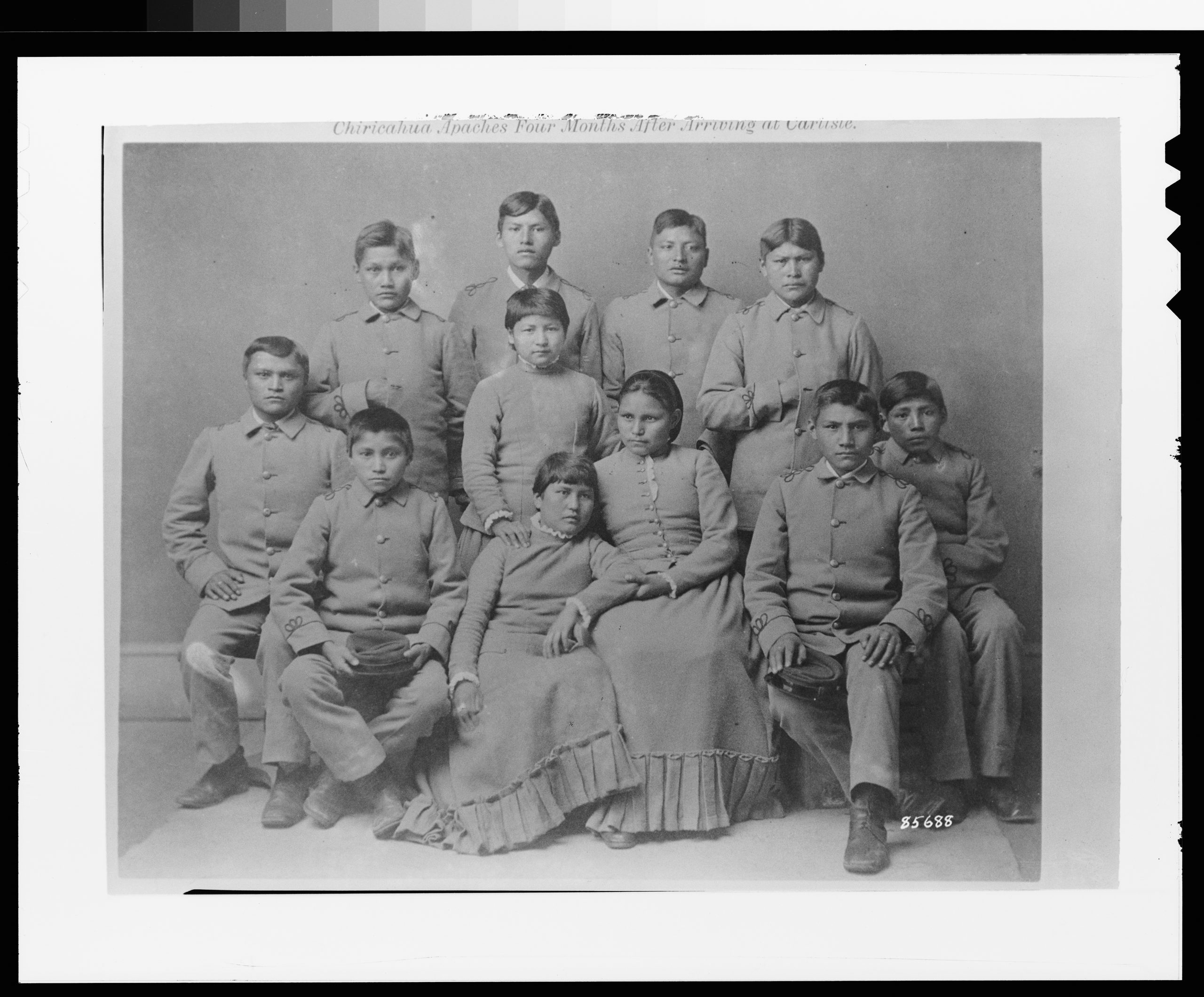

Native American Boarding Schools: Cultural Imperialism and Genocide

Using its military, the federal government created several Native American boarding schools nationwide. Native American boarding schools were designed to take away Indigenous culture and assimilate Indigenous children into mainstream American culture. The first and most famous boarding school was the Carlisle School, founded in Pennsylvania in 1879. The federal government convinced many Native American parents that these off-reservation boarding schools would educate their children to improve their economic and social opportunities in mainstream America.

This experiment was intended to deculturize Indigenous children. Supervisors at the boarding schools destroyed children’s native clothing, cut their hair, and renamed many of them with names chosen from the Protestant Bible. The curriculum in these schools taught basic literacy and focused on industrial training, intended to sort graduates of these boarding schools into agricultural and mechanical occupations. A total of 25 off-reservation boarding schools educating nearly 30,000 students were created in several western states and territories, as well as in the upper Great Lakes region. Based on ethnocentrism, or the belief of the White, Protestant mainstream culture that they were superior to other cultures, these boarding schools relied on a harsh form of assimilation, a fundamental feature of common schooling.

Deeper Dive

Deeper Dive

Indigenous Boarding Schools in the News

In the summer of 2021, the dark history of Indigenous boarding schools made headlines as Canadian authorities discovered unmarked graves and remains of children killed at multiple boarding schools for Indigenous children. In July 2021, the U.S. launched a federal probe into our own Indigenous boarding schools and the intergenerational trauma they have caused. These boarding schools are one way that education has been used to oppress and deculturize a particular group of Americans.

Conclusion

From Puritan Massachusetts to post-Civil War, many essential changes occurred regarding who could receive education and how they received it. As you can see, access to education was seen as a way to provide betterment to society, but some populations were not included in this vision. Hence, they had to find other ways to educate their people.

References

Anderson, J. D. (1988). The education of blacks in the South, 1860-1935. University of North Carolina Press.

Butchart, R. E. (2010). Schooling the freed people: Teaching, learning, and the struggle for black freedom, 1861-1876. University of North Carolina Press.

Cremin, L. A. (1972).American education: The colonial experience, 1607-1783. Harper Collins.

Elazar, D. J. (1969). Cooperation and conflict: Readings in American federalism. F. E. Peacock, Inc.

Foner, E. (2012). Give me Liberty! An American history. W. W. Norton & Company.

McClellan, B. E. (1999).Moral education in America: Schools and the shaping of character from colonial times to the present. Teachers College Press.

Powell, S. D. (2019). Your introduction to education: Explorations in teaching (4th ed.). Pearson.

Urban, W. J., & Wagoner, J. L. (2009). American education: A history (4th ed.). Routledge.

Waldman, K. (2015, May 19). Slave or enslaved person? Slate. https://slate.com/human-interest/2015/05/historians-debate-whether-to-use-the-term-slave-or-enslaved-person.html

Webster, N. (1965). On the education of youth in America. In F. Rudolph (Ed.), Essays on education in the early republic, pp. 41-77. The Belknap Press of Harvard University.

- The following chapter is revised from Foundations of American Education: A Critical Lens (Chapter 3) by Melissa Wells and Courtney Clayton, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License ↵