Historical Foundations: Post-WWII-Present Day

Preparing to Learn

Preparing to Learn

Historical Foundations: Post-WWII-Present Day

Before discussing the historical foundations of education, complete the assessment below to check what you already know, what you need to unlearn, and what you might be interested in exploring further.

Historical Foundations

Post World War II & Civil Rights Era[1]

In the decades following World War II, the U.S. prospered, and education saw many significant shifts, especially focusing on equality of educational opportunities. In this period, ongoing inequalities in educational opportunities led to limited federal funding, Brown v. Board of Education (1954) deemed segregated schools illegal, and other minoritized groups continued to fight for equitable access to education.

Ongoing Inequalities and Federal Funding

The 1945 Senate committee hearings on federal aid to education highlighted ongoing inequities in schooling and the fact that “education was in a state of dire need” of financial resources and more equitable funding (Ravitch, 1983, p. 5). Most school funding came from property taxes, which continued to exacerbate inequities. Other changes took place following World War II to worsen already existing inequalities. After the War, “white flight” from the inner city to the suburbs resulted in highly-segregated communities, falling urban property values, and rising suburban property values. White flight contributed to greater de facto segregation, and it increased segregated schooling and enhanced inequalities in school funding.

In response, the federal government offered limited assistance. The National School Lunch Program was passed in 1946 to enhance learning through better nutrition. In response to the anxiety created over the launching of the Russian satellite Sputnik, Congress passed the 1958 National Defense Education Act, which provided increased federal funding for math, science, and foreign languages in public schools. While these examples are not exhaustive, they illustrate the piecemeal federal approach to funding public schools: if a problem was perceived as a crisis and reached the federal legislative agenda, it was more likely to attract congressional funding.

In 1965, President Johnson worked with Congress to pass what became known as the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA). The ESEA served as the largest total expenditure of federal funds for the nation’s public schools. Aligned with Johnson’s war against poverty, the purpose of the law included increased federal funding for school districts with high levels of poor students. The law included six Titles (sections). Title I was the primary legislative focus, including about 80 percent of the law’s total funding. Title I funds were distributed to poorer school districts to remedy the unequal funding perpetuated by reliance on property taxes. Title VII, or the Bilingual Education Act of 1968, provided funds for students who were speakers of languages other than English. The other Titles provided federal funding for school libraries, textbooks and instructional materials, educational research, and funds to state education departments to help them implement and monitor the law. This resulted in the growth of state power alongside the expansion of federal power since states gained greater oversight of federal programs and mandates.

In 1954, the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision ended the separate-but-equal doctrine, which was established in 1896 by the Plessy v. Ferguson case. In Plessy v. Ferguson, the U.S. Supreme Court circumvented the original intent of the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause, which was intended to give all persons equal rights under the law. The Court strategically interpreted the clause to mean they were constitutional as long as segregated public facilities were equal. The Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka case, however, changed this. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) found five plaintiffs representing four states (Delaware, Kansas, South Carolina, and Virginia) and the District of Columbia to challenge segregated primary and secondary schools. All five cases were heard under Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. The Court ruled unanimously in 1954 to overturn Plessy. In his majority decision, Chief Justice Earl Warren made the following conclusion:

“Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children. The impact is greater when it has the sanction of the law, for the policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the Negro group… Any language in contrary to this finding is rejected. We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” (347 U.S. 483, 1954)

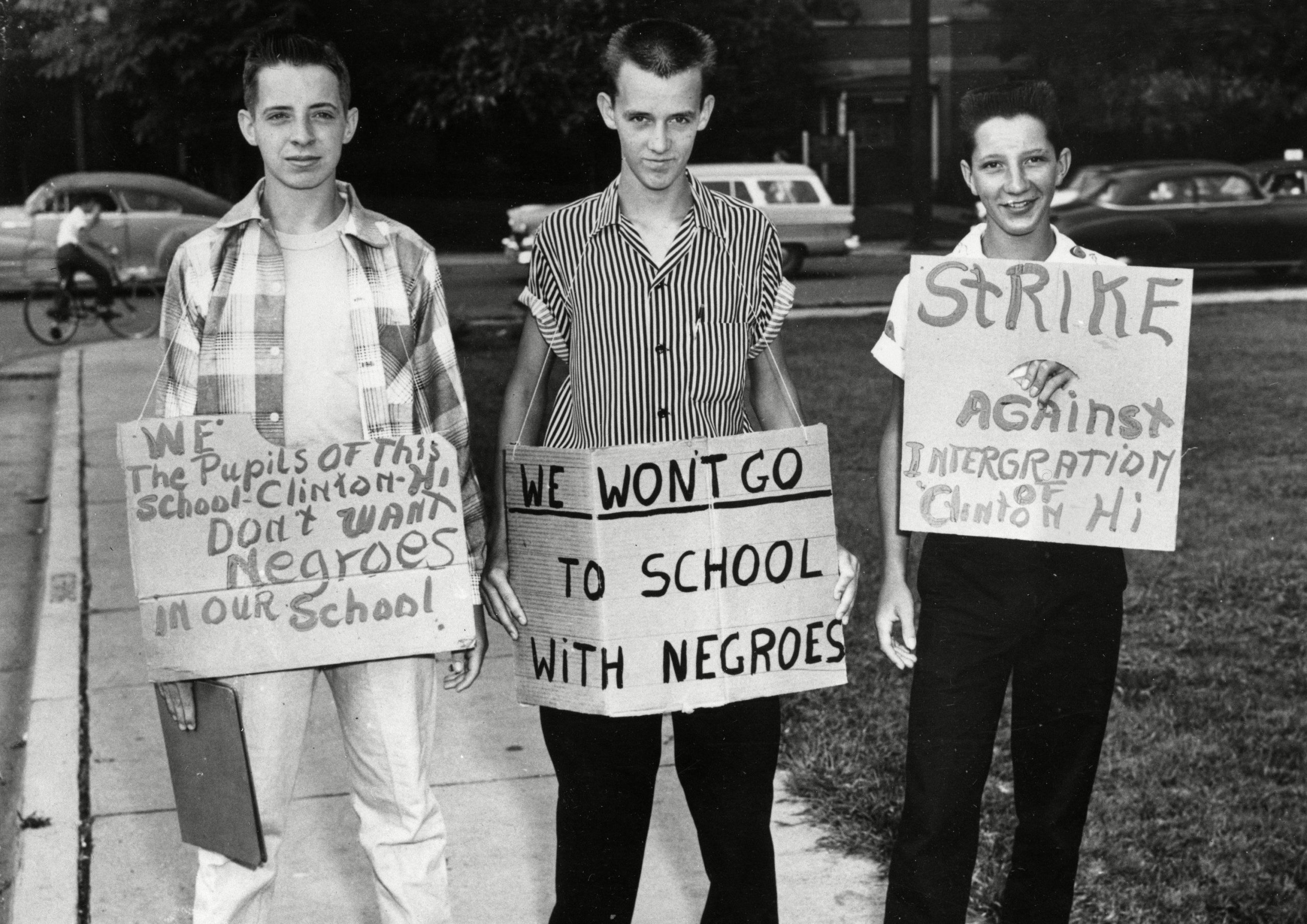

U.S. DESEGREGATION PROTEST, CLINTON, USA

After ruling segregation unconstitutional, the Court had to consider a reasonable set of remedies to ensure desegregation. In 1955, The Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka II that desegregation would occur “on a racially nondiscriminatory basis with all deliberate speed.” This vague language, particularly “all deliberate speed,” contributed to the chaos and enabled state resistance, with each state and district deciding its own approaches or avoidance thereof (Ryan, 2010).

When integration did take place, it occurred on white terms. Integration resulted in Black teachers losing their jobs and the closing of their schools. Black students were integrated into White schools and were suddenly being taught by White teachers while being subjected to an all-white curriculum. Black students and teachers alike experienced “cultural dissonance that exacerbated student rebelliousness, especially among African American boys.” Furthermore, “the actual implementation of integration plans and court orders remained largely in the hands of white school boards” (Fairclough, 2007, p. 396-400). Due to massive resistance to desegregation, Congress passed the 1964 Civil Rights Act as an attempt to force compliance. Following the passage of ESEA, which provided millions of federal dollars to each state, the federal government could now threaten non-compliant states (and school systems) by withholding large sums of money annually under Title VI of the act.

Many urban school systems began drawing plans to bus white and non-white children to schools across neighborhoods to increase racial diversity in all a district’s schools (i.e., Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 1971). However, in 1974, the U.S. Supreme Court decided schools were not responsible for desegregation across district lines if their policies had not explicitly caused the segregation when the case Milliken v. Bradley was heard. President Nixon, who opposed inter-district busing, argued that to protect suburban schools, inner-city schools should be given additional funds and resources to compensate urban school children for the harms of past segregation and the legacies of inequitable funding (LCCHR, n.d.). According to Ryan (2010), “Nixon’s compromise, broadly conceived to mean that urban schools should be helped in ways that [did] not threaten the physical, financial, or political independence of suburban schools… continues to shape nearly every modern education reform” (p. 5). The Milliken decision halted any possibility to integrate schools effectively. Due to the existence of de facto segregation, there was no significant way to integrate students unless they crossed district boundaries.

Nixon also worked with Congress to pass the 1974 Equal Educational Opportunities Act. This legislation embodied all children’s rights to equal educational opportunities, and it included consideration for students with limited English proficiency (LEP). The law’s intent exemplifies the EEOA’s applicable breadth, which prohibits states from denying equal educational opportunity based on race, color, sex, or national origin. Moreover, the EEOA prohibits states from denying equal educational opportunity by the failure of an educational agency to take appropriate action to overcome language barriers that impede equal participation by its students in its instructional programs.

Increasing Access to Education for Minoritized Groups

The African American Civil Rights Movement gave hope to Mexican and Asian Americans, as well as women, people with disabilities, and, to a lesser extent, Native Americans. Like African Americans, Mexican Americans utilized the courts to overturn segregated schools in the southwest, particularly in Texas and California. The earliest segregation case was filed by Mexican Americans in 1931 in Lemon Grove, California. Other cases would be filed in the 1940s and 1950s, including Mendez v. Westminster in 1947.

Reflect

Reflect

Disegregation of Schools

A class action suit in San Francisco, California, led to legal rights for English Language Learners. In Lau v. Nichols (1974), parents of approximately 1,800 non-English-speaking Chinese students alleged that their Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection rights had been violated since they could neither understand nor speak English, the language of instruction, which meant their children were not benefitting from educational services. The U.S. Supreme Court concluded that the school district violated Section 601 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which banned discrimination based “on race, color, or national origin” in “any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.” As recipients of federal funds, schools were required to respond to the needs of English language learners effectively, whether this meant implementing bilingual education, English immersion, or some other method of instruction. The Court concluded, “Under these state-imposed standards there is no equality of treatment merely by providing students with the same facilities, textbooks, teachers, and curriculum; for students who do not understand English are effectively foreclosed from any meaningful education.”

Historically, children with special needs have been excluded from many educational opportunities and now have increased access to education. In 1972, the Pennsylvania Association for Retarded Children (PARC) v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania case guaranteed the rights of children with disabilities to attend free public schools. Congress followed up in 1973 by enacting the Rehabilitation Act, which guaranteed civil rights for people with disabilities, including appropriate accommodations and individualized education plans to tailor education for students based on their unique needs. Providing children with disabilities in the least restrictive settings was implemented in the 1975 Education for All Handicapped Children Act.

Women continued to fight for equal pay and respect in the workplace, and some success was achieved in the passage of Title IX as one of the amendments to the 1972 Higher Education Act. Title IX “prohibits discrimination based on sex in any federally funded education program or activity” in “colleges, universities, and elementary and secondary schools,” as well as to “any education or training program operated by a receipt of federal financial assistance,” including intercollegiate athletic activities (The U.S. Department of Justice, n.d.).

Native Americans were able to enjoy greater control in limited ways over reservation schools, including but not limited to the Rough Rock Demonstration School (recently renamed Rough Rock Community School), located in northeastern Arizona. A collaboration between the Office of Economic Opportunity and the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the school opened in 1966 intending to give “Navajo parents…control” over “the education of their children” and to “participate in all aspects of their schooling.” Moreover, these efforts served as an “attempt to preserve the Navajo language and culture,” which was “in contrast to the deculturalization efforts of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries” (Spring, 2008, p. 394). Although the history of federal and Native Indian relations consisted of genocide, relocation, dispossession, and controlled boarding school experiments, Rough Rock Demonstration School continues to provide an example of Navajo empowerment and a locally developed form of Native cultural redemption.

The 1980s and Beyond

In the 1980s and beyond, education saw increasing federal supervision and support, though ultimate control of education remained with individual states. In this period, the Department of Education was established, A Nation at Risk led to standards-based reform like No Child Left Behind, and social-emotional learning emerged.

Establishing the Department of Education

While the federal government has no constitutional authority over public education, its power and influence over schooling has reached a pinnacle since the 1980s. In 1979, President Jimmy Carter created the federal Department of Education. Ronald Reagan, who succeeded Carter, tried and failed to abolish it. Reagan’s neo-conservative followers primarily consisted of traditionalists and evangelicals. The traditionalists believed moral standards and respect for authority had declined since the 1960s, while evangelicals (also known as the Religious Right) were concerned about increasing U.S. secularism and materialism (Foner, 2012). For example, in Engel v. Vitale (1962), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that directed prayer in public schools violated the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause, which forbids the state (public schools and their employees) from endorsing or favoring religion. While the Religious Right saw this decision as taking God out of America’s public schools, the Court viewed the separation of church and state as necessary to protect religious freedoms from government intrusion. As established earlier in this chapter, however, the moral values taught in the public schools were often based on or connected to Protestant Christianity, so complete separation of church and state in schools was impossible.

A Nation at Risk and Standards-Based Reform

In 1981, Reagan created the National Commission on Excellence in Education to address the perceived problems of educational decline. In 1983, the commission released a 71-page report entitled A Nation at Risk. The authors of the report, who were primarily from the corporate world, declared, “American students never excelled in international comparisons of student achievement and that this failure reflected systematic weaknesses in our schools and lack of talent and motivation among American educators” (Berliner & Biddle, 1995, p. 3). However, A Nation at Risk was somewhat “sensational” (Urban & Wagoner, 2009, p. 402), containing numerous claims that were uncorroborated or misleading generalizations as a pretense for a larger political agenda intended to discredit public schools and their teachers.

Developing the perception that America’s schools were in crisis, A Nation at Risk justified a top-down, punitive approach to school reform. While standards-based reform had been around for several years as primarily a state issue, it “provided new theories about ‘systemic’ reform, which emphasized renewing academic focus in schools, holding teachers accountable for educational outcomes, measured by students’ academic achievement, and aligning teacher preparation and pedagogical practice with content standards, curriculum, classroom practice, and performance standards” (DeBray, 2006, p. xi).

The No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB, 2001) was an example of standards-based reform. As a bipartisan-passed reauthorization of the 1965 Elementary and Secondary Education Act, it was “the first initiative to truly bring the federal government as a regulator into American public education” (Fabricant & Fine, 2012, p. 13). Before, the federal government’s outreach typically extended only to funding; now, NCLB would hold schools, teachers, and students accountable for passing numerous standardized tests annually in math and reading in grades 3-12. The law also required states to test English language learners for oral, written, and reading proficiency in English each year.

Critiques of NCLB include the acute focus on standardized testing and teaching to the test, uniform curricula that have little or no connection to an increasingly diverse student population, and the punitive nature of the law on students, teachers, and administrators. Madaus et al. (2009) asserted that testing “is now woven into the fabric of our nation’s culture and psyche,” which is evidenced by the fact that even “the valuation of homes in a community can increase or decrease based on these rankings” (p. 4-5). The most problematic nature of NCLB is its supporters’ assumption that uniformity, standardization, centralization, and punitive measures can compel learning and decrease achievement gaps. Assumptions that all children learn uniformly in all respects reveal a lack of understanding of the complexity of the learning process and the various demographic differences among children in a diverse society, including cultural, language, and ability differences.

In 2015, the No Child Left Behind Act (originally the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965) was reauthorized as the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). The law:

- Advances equity by upholding critical protections for America’s disadvantaged and high-need students.

- Requires that all students in America be taught to high academic standards that will prepare them to succeed in college and careers.

- Ensures that vital information is provided to educators, families, students, and communities through annual statewide assessments that measure students’ progress toward those high standards.

- Helps to support and grow local innovations, including evidence-based and place-based interventions developed by local leaders and educators.

- Sustains and expands investments in increasing access to high-quality preschool.

- Maintains an expectation that there will be accountability and action to effect positive change in our lowest-performing schools, where groups of students are not making progress, and where graduation rates are low over extended periods of time (U.S. Department of Education, n.d.).

Critical Perspective

Critical Perspective

Standardized Testing

In a society experiencing greater diversity, it is more important than ever to realize how culture plays a significant role in shaping children’s school experiences, making standardized assessments all the more problematic as they tend to be culturally biased. Therefore, relying on standardized assessments to draw conclusions about student achievement (or lack of achievement) makes it all the more difficult for teachers to respond appropriately to their students’ cognitive abilities. Rote memorization and test preparation skills can easily inhibit creativity and imagination, not to mention the fact that this kind of educational focus is teacher-centered, less dynamic, and assimilatory.

By specifically tying federal funds to standardized assessments, standardized curricula, and accountability measures, along with requiring states and state education agencies to devote extraordinary resources toward fulfilling these mandates through oversight, America’s public schools were being governed by the federal government like never before. Increased federal influence illustrates the underlying belief that if the U.S. is going to maintain economic superiority and global competitiveness, public schooling must become a national responsibility. Contemporary goals focusing on preparing children to compete globally are significant for several reasons, including the evolving nationalization of our public schools and the simultaneous loss of local authority and discretion over fundamental matters related to student learning.

Social Emotional Learning

Recently, educators have advocated for a more holistic approach to education beyond testing. Social-emotional learning (SEL) is “the process through which we learn to recognize and manage emotions, care about others, make good decisions, behave ethically and responsibly, develop positive relationships, and avoid negative behaviors” (Edutopia, 2011, para. 3). Advocates of SEL note that these skills will support students’ personal development and academic performance simultaneously. Early pilots of SEL-influenced approaches to education occurred in the 1960s in New Haven, Connecticut, with two low-achieving schools serving primarily African American students. By the early 1980s, these two schools’ academic performance was above the national average. In 1994, the Collaborative to Advance Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL) was established. Goleman’s book Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More than IQ brought this concept into popular culture (Edutopia, 2011). ASCD’s “Whole Child Approach” continues to advocate for education that keeps students healthy, safe, engaged, supported, and challenged (ASCD, n.d.).

Summary

Education in the United States has a complicated past entrenched in religious, economic, national, and international concerns. In Colonial America, Puritans in Massachusetts knew education would teach children the ways of religion and laws, which were vital to survival in a new world. Meanwhile, the Middle and Southern Colonies viewed education as a commodity for the wealthy families who could afford it. After the American Revolution, Federalists, Anti-Federalists, and Democratic-Republican Societies had different perceptions of how schools should be organized to support our newly established independent nation. In the Early National Era, common schools, normal schools, and higher education grew as education became more widely established. Following the Civil War, the federal government was increasingly involved in education, including the temporary creation of the Freedmen’s Bureau and subsequent federal funding of agricultural and mechanical colleges with the passage of the Morrill Acts. In the Progressive Era, efforts to maximize educational systems’ efficiency and utilize education as a venue for social reform prevailed. After World War II, equitable access to education became a primary focus, as “separate-but-equal” doctrines were overthrown and schools grappled with institutional discrimination against non-White students, students with disabilities, women, and English Learners. The 1965 Elementary and Secondary Education Act provided federal funds to public schools, while states and local school districts continued to exercise considerable discretion over curriculum, assessments, and teacher certification. In the 1980s and beyond, increased pressures for standardization and accountability resulted in standards-based reform, including the No Child Left Behind Act in 2001. More recently, education has been leveraged to support a student’s developmental needs, not just academics. Common educational philosophies, including perennialism, essentialism, progressivism, and social reconstructionism, reflect varying beliefs about the roles education should fill.

Like learning, teaching is always developing; it is never realized once and for all. Our public schools have always served as sites of moral, economic, political, religious, and social conflict and assimilation into a narrowly defined standard image of being an American. According to Britzman (as quoted by Kelle, 1996), “the context of teaching is political, [as] it is an ideological context that privileges the interests, values, and practices necessary to maintain the status quo.” Teaching is by no means “innocent of ideology,” she declares. Instead, the context of education tends to preserve “the institutional values of compliance to authority, social conformity, efficiency, standardization, competition, and the objectification of knowledge” (p. 66-67).

It should be no surprise that contemporary public education debates continue to reflect our most profound ideological differences. As Tyack and Cuban (1995) have noted in their historical study of school reform, the nation’s perception toward schooling often “shift[s]… from panacea to scapegoat” (p. 14). We would go a long way in solving academic achievement and closing educational gaps by addressing the broader structural issues that institutionalize and perpetuate poverty and inequality.

Knowledge Check

Knowledge Check

Historical Foundations: Post-WWII-Present Day

References

Berliner, D. C., & Biddle, B. J. (1995). The manufactured crisis: Myths, frauds, and the attack on America’s public schools. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). https://www.oyez.org/cases/1940-1955/347us483

DeBray, E. H. (2006). Politics, ideology, & education: Federal policy during the Clinton and Bush administrations. Teachers College Press.

Edutopia (2011, October 6). Social and emotional learning: A short history. https://www.edutopia.org/social-emotional-learning-history

Engel v. Vitale, 370 U.S. 421 (1962). https://www.oyez.org/cases/1961/468

U.S. Department of Education (n.d.). Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). https://www.ed.gov/essa?src=ft

Fabricant, M., & Fine, M. (2012). Charter schools and the corporate makeover of public education: What’s at stake? Teachers College Press.

Fairclough, A. (2007). A class of their own: Black teachers in the segregated South. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Foner, E. (2012). Give me Liberty! An American history. W. W. Norton & Company.

Kelle, J. F. (1996). To illuminate or indoctrinate: Education for participatory democracy. In J. N. Burstyn (Ed.), Educating tomorrow’s valuable citizen, pp. 59-76. State University of New York Press.

Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974). https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/414/563/

Madaus, G., Russell, M., & Higgins, J. (2009). The paradoxes of high stakes testing: How they affect students, their parents, teachers, principals, schools, and society. Information Age Publishing, Inc.

Ryan, J. E. (2010). Five miles away, a world apart: One city, two schools, and the story of educational opportunity in modern America. Oxford University Press.

Spring, J. (2008). The American school: A global context from the Puritans to the Obama era (8th ed.). McGraw Hill.

The U.S. Department of Justice (n.d.). Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972. https://www.justice.gov/crt/fcs/TitleIX-SexDiscrimination

Tyack, D., & Cuban, L. (1995). Tinkering toward utopia: A century of public school reform. Harvard University Press.

Urban, W. J., & Wagoner, J. L. (2009). American education: A history (4th ed.). Routledge.

- The following chapter is revised from Foundations of American Education: A Critical Lens (Chapter 3) by Melissa Wells and Courtney Clayton, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License ↵