Main Body

9 Public Health Workforce

Hector (Giovanni) Antunez

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to:

There is a need for more public health workers

The need for more of these workers to have a formal education in public health, the more prepared the most efficient the work will be. This also calls for more schools of public health, and more funding to place and replace (those who have been retired from the workforce) the graduates from these schools. In a previous chapter in this textbook, the need for more nurses and medical doctors [as the two most common healthcare workers] was emphasized. Now, this chapter will look at the need for more public health workers and not only those healthcare workers but anyone [or, the majority] of workers in the public health field.[1]

Who are the public health workers?

The answer to this question is twofold, first, the individuals involved in carrying out the core functions and essential services of public health are the public health workforce. Second, the job description for the entire population of public health workers is based on the 10 Essential Public Health Services.[2] Also as mentioned in the previous chapter, public health workers are those individuals who have been trained in public health formally and informally, the latter applies to those current public health workers who learn how to do the job without having a public health degree. The formal refers to those public health workers who have attended accredited universities and graduate programs in public health.

The size and distribution of the public health workforce have been always hard to enumerate, not only due to a problem in the definition of a ‘public health worker,’ but also the lack of compatible data [in the past] to make comparisons in the present. A general idea of the size of the public health workforce can be obtained by looking at the FTEs (Full Time Equivalent) of federal, state, and local governmental health agencies reported annually by the U.S. Bureau of Census, public employment, and payroll data behaviors. Based on these sources, it is estimated that there is an approximate public health workforce that consists of 448,254 individuals in salaried positions as follows: 44.6 percent professionals, 4 percent officials/administrators, 14 percent technicians, and 13 percent clerical/support. [3]

Conventional Wisdom?

Most people believe that in the U.S. the public health workforce is shrinking, and is getting older (with an average age of approximately 47 years old) which means that a lot of public health workers soon will be retiring in large numbers; meaning that there is a great need for recruitment and retention which is hard, especially for jobs in rural communities; some areas of expertise are scarce, especially disciplines such as public health nurses and epidemiologists; there are also a lot of current public health workers who have no formal training, they have been learning their jobs while doing it, and overall, many of these public health workers are not prepared for current and future threats and emergencies. [4]

Going beyond conventional wisdom

Besides what conventional wisdom said, see what people in the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health reported, which is summarized here for you. In the recent years of pandemic from COVID-19, the problem has been exacerbated as a recent study from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health reported, “Nearly half of all employees in state and local public health agencies in the U.S. left their jobs between 2017 and 2021, and if such workforce contractions continue, more than 100,000 public health staff could leave their jobs by 2025.”[5]

What is making the public health workforce shrink?

Researchers at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health found that 46% of all employees in state and local public health agencies left their jobs during the five-year study period.

If the current rate of attrition in the governmental public workforce continues, it could translate to a potential loss of 129,000 workers over the next two years, the study found. Who resigned? Resigning was particularly common among younger staff: 75% of employees ages 35 or younger or with shorter tenures left their jobs.

What other factors could have contributed to these resignations? The co-authors speculated that pandemic-related challenges facing public health workers—including criticism, harassment, and personal threats—likely fueled the hefty job exodus. The data in this textbox is from a recent study conducted by the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. [6]

How do we increase the numbers in the public health workforce?

Several strategies have been put in place, and these are known as Pipeline strategies. The most common of these strategies have been the provision of scholarships and loan repayment programs for those going into public health schools/programs. Also, several schools of public health have been making enormous efforts to recruit/attract and graduate more students in the field.

Going into the “Who” represented as the Public Health Workforce in the U.S.

Now that a general overview of who are the public health workers, its numbers, and current challenges including the shrinking nature of these numbers, let’s see who are these people. To find data about the characteristics of the U.S. workforce, it has been customary to use the Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey (PH WINS) conducted by the de Beaumont Foundation and the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO). There have been a series of needs surveys conducted over the years, in 2014, 2017, and 2021 and a new one is coming in September 2024. The needs surveys collect data on the demographics of the government’s public health workforce and capture individual public health workers’ perspectives on key issues.[7]

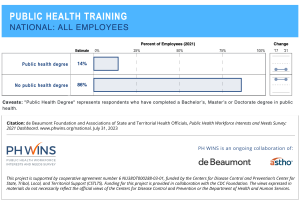

Using the most recent needs survey of 2021.[8] The following are some of the results.

Demographics of the U.S. Public Health Workforce

Ethnicity: The 2021 PH WINDS survey reported that most public health workers self-identify as white (54%).

|

| “Race and Ethnicity,” Screenshot from the 2021 PH WINDS survey, Dashboard, Fair Use. |

The report comments that “While the workforce has become more diverse and now mirrors the U.S. population more closely, there is much less diversity at senior levels, with 66% of all executives identifying as white.”[9]

|

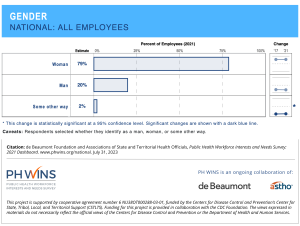

| “Gender,” Image downloaded from the 2021 PH WINDS survey, Dashboard, Fair Use. |

Gender: The 2021 PH WINDS survey reported that most public health workers self-identify as women (79%). Details are presented in the graph.

|

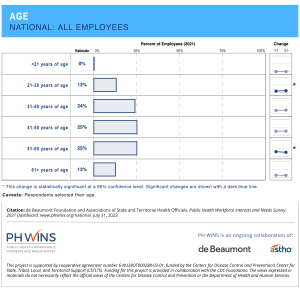

| “Age,” Image downloaded from the 2021 PH WINDS survey, Dashboard, Fair Use. |

Comments: as seen in these graphs provided by The 2021 PH WINDS survey most of the comments and observations made about these characteristics of the U.S. workforce are confirmed.

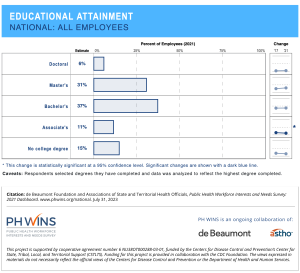

Education: it is important to give a quick look at the levels of education reported by The 2021 PH WINDS survey. Data shows – as an aggregate made by the author, that having a bachelor’s or a master’s degree represent the majority of the educational attainment.

|

| “Educational Attainment,” Image downloaded from the 2021 PH WINDS survey, Dashboard, Fair Use. |

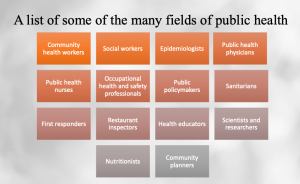

Comments: Related also to formal educational level it is the topic of occupation. At the beginning of this book, looking at the list of occupations or most common jobs of public health workers it can be seen that the jobs of public health workers include a variety of areas of knowledge, skills and expertise. Many of the occupations of public health workers revolved around the many fields that are directly or indirectly related to public health – see image below:

|

| Image created by Giovanni Antunez using MS PowerPoint. Licensed CC BY-SA 4.0 The list was prepared by using a web article from the American Public Health Association.[10] |

|

| “Public Health Training,” Image downloaded from the The 2021 PH WINDS survey, Dashboard, Fair Use. |

Program area: this characteristic is helpful to see what are the most common areas in which public health workers do their work. See image below:

|

| “Program area,” Image downloaded from the The 2021 PH WINDS survey, Dashboard,Fair Use. |

Credentialing: this is the next level of information that is also useful to look at for the U.S. public health workforce is the credential of these workers.

What are the most common credentials found in public health workers?

Most people agree that having a credential means that the person or the organization has met a series of standards for their profession. Currently, more and more institutions especially those in higher education are seeing the need for more credentialing, especially in those areas in which credentialing has been not required.[11]

|

| “CPH,” image from Quora. Fair Use. |

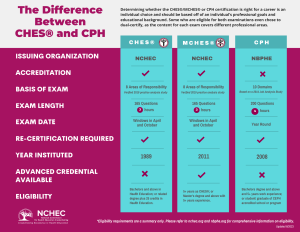

What type of credentials are the most common in public health? To answer this question, it is accepted that one highly recommended credential for public health workers is the Certified in Public Health (CPH), which has been offered in the U.S. since 2008 by the National Board of Public Health Examiners. The CPH credential is for graduates of master’s degree programs accredited by the Council on Education in Public Health. [12]

The Council on Education for Public Health (CEPH) is the same that also provides accreditation for Public Health Programs. [13] In this context, how many public health workers has been certified since 2008? An estimate by the Association of Public Health Nurses (APHN) reported that as many of 10,000 individuals have been certified with CPH. The Certified in Public Health (CPH) exam covers the areas of knowledge relevant to contemporary public health and general principles. [14]

The CPH examination was crafted to assess a person’s knowledge of the following competencies as presented in detail in the table below.

| The Certified in Public Health (CPH) Content | |

| Competency areas | Percent (%) covered |

| Evidence-Based Approaches to Public Health | 10% |

| Communication | 10% |

| Leadership | 10% |

| Law and Ethics | 10% |

| Public Health Biology and Human Disease Risk | 10% |

| Collaboration and Partnership | 10% |

| Program Planning and Evaluation | 10% |

| Program Management | 10% |

| Policy in Public Health | 10% |

| Health Equity and Social Justice | 10% |

| Table prepared using information fromAssociation of Public Health Nurses (APHN). (n.d.). CPH Credential. From https://www.phnurse.org/cph-credential | |

Is there any difference between the CPH certification and the CHES/MCHES certification?

|

| “The difference between CHES and CPH,” image from NCHEC, Fair Use. |

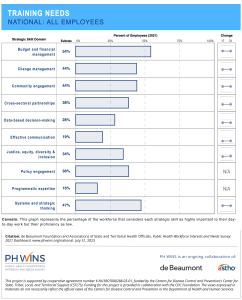

Training Needs of the Public Health Workforce

In addition, the PH WINS 2021 Survey reported also the main Training Needs of U.S. Public Health Workers as reported. These training needs and skills are presented in the image below.

|

| “Training Needs,” Image downloaded from the The 2021 PH WINDS survey, Dashboard, Fair Use. |

Public Health 3.0, although there is more to say, the essence of the definition is around, “Transforming Communities. Public Health 3.0 emphasizes collaborative engagement and actions that directly affect the social determinants of health inequity.” This period emphasizes the work with communities and the different active organizations and institutions in those communities. [17]

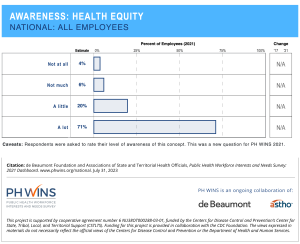

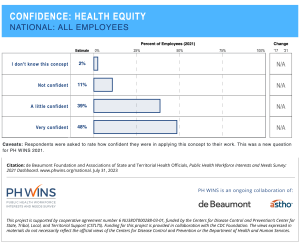

Health Equity Concepts

Since the recent importance of health equity in public health and healthcare systems in the United States, the PH WINS 2021 Survey explored the level of awareness about the issue, the level of confidence of U.S. Public Health Workers in this important area. The main results are presented in the images below.

|

| “Awareness on Health Equity,” image from the 2021 PH WINS Survey Dashboard, Fair Use. |

The survey measured the public health workforce’s awareness of and confidence in applying five concepts: health equity, social determinants of equity, social determinants of health, structural racism, and environmental justice.[18],[19],[20],[21],[22]

|

| “Confidence on Health Equity,” image from the 2021 PH WINS Survey Dashboard, Fair Use. |

The 2021 PH WINS respondents were less confident with the health equity concepts compared to the high-rating on-health equity awareness; which is kind of expected since digesting and applying these concepts takes time because it is a process.

- Gebbie K, Rosenstock L, Hernandez LM, editors. (2003). Who Will Keep the Public Healthy? Educating Public Health Professionals for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 5, The Need for Public Health Education in Other Programs and Schools. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK221177/ ↵

- CDC. (n.d.). 10 Essential Public Health Services. From https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/publichealthservices/essentialhealthservices.html ↵

- Gebbie, K., Merrill, J., Hwang, I., Gebbie, E. N., & Gupta, M. (2003). The public health workforce in the year 2000. Journal of public health management and practice: JPHMP, 9(1), 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1097/00124784-200301000-00011 ↵

- Bogaert, K., Castrucci, B. C., Gould, E., Sellers, K., Leider, J. P., Whang, C., & Whitten, V. (2019). The Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey (PH WINS 2017): An Expanded Perspective on the State Health Agency Workforce. Journal of public health management and practice : JPHMP, 25 Suppl 2, Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey 2017(2 Suppl), S16–S25. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000000932 ↵

- Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. (2023, March 8). U.S. governmental public health workforce shrank by half in five years, study finds. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health News. From https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/hsph-in-the-news/u-s-governmental-public-health-workforce-shrank-by-half-in-five-years-study-finds/ ↵

- Content used to prepare the textbox comes from the following source: Leider, J.P., Castrucci, B.C., Robins, M., Hare Bork, R., Fraser, M.R., Savoia, E., Piltch-Loeb, R., Koh, H.K. (2023, March). The Exodus Of State And Local Public Health Employees: Separations Started Before And Continued Throughout COVID-19. Health Affairs, 42(3). From https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2022.01251 ↵

- de Beaumont Foundation and the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO). (n.d.). PH WINS (the Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey). From https://debeaumont.org/phwins/what-is-phwins/ ↵

- de Beaumont Foundation and the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO). (n.d.). 2021 National Findings Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey. From https://debeaumont.org/phwins/2021-findings/ ↵

- de Beaumont Foundation and the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO). (n.d.). Page Screenshots and comments taken 2021 National Findings Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey. From https://www.phwins.org/national/dashboard?&type=public&fi=0_1&topic=1&fe=all_employees&c=nothing&ci=OFF&dl=point_estimate&sort=def ↵

- American Public Health Association (APHA). (n.d.). What is Public Health? From https://www.apha.org/What-is-Public-Health ↵

- Patel R, Sharma S. Credentialing. [Updated 2022 Oct 24]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519504/ ↵

- National Board of Public Health Examiners. (n.d.). Certified in Public Health (CPH). From https://www.nbphe.org/ ↵

- Council on Education for Public Health (CEPH). Accreditation for Public Health Programs. From https://ceph.org/ ↵

- Association of Public Health Nurses (APHN). (n.d.). CPH Credential. From https://www.phnurse.org/cph-credential ↵

- National Center for Health Education and Credentialing (NCHEC).(n.d.). Examination Statistics. From https://www.nchec.org/overview ↵

- National Center for Health Education and Credentialing (NCHEC).(n.d.). The difference between CHES and CPH. From https://www.nchec.org/assets/2251/rev_june_2023.png ↵

- NACCHO (National Association of County and City Health Officials). (n.d.). Public Health 3.0 Transforming Communities. Available at https://www.naccho.org/programs/public-health-infrastructure/public-health-3-0 ↵

- City Health. (n.d.). Health Equity. de Beaumont Foundation. From https://www.cityhealth.org/about-us/equity-statement/ ↵

- Baciu A, Negussie Y, Geller A, et al., editors. (2017, Jan 11). Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 3, The Root Causes of Health Inequity. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK425845/ ↵

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Healthy People 2030. From https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health ↵

- Aspen Institute. (2016). Racial Equity, 11 Terms you should know to better understand structural racism. From https://www.aspeninstitute.org/blog-posts/structural-racism-definition/ ↵

- EPA. (2023). Environmental Justice in Enforcement and Compliance Assurance. From https://www.epa.gov/enforcement/environmental-justice-enforcement-and-compliance-assurance ↵

The term, "Conventional wisdom" or received opinion is the body of ideas or explanations generally accepted by the public and/or by experts in a field.

The term is commonly used in sales, and in general, a pipeline strategy is "a systematic or thoughtful approach that guides new leads/prospects through each stage of the process (pipeline)".

Health equity means all people, regardless of who they are, where they came from, how they identify,

where they live, or the color of their skin, have a fair and just opportunity to live their healthiest possible lives - in body, mind, and community. (CityHealth, Health Equity. From https://www.cityhealth.org/about-us/equity-statement/ )

The social determinants of equity are systems of power like racism, sexism, heterosexism, ableism, and economic systems like capitalism. The social determinants of equity determine the range of contexts available and who is found in which context. (Jones, 2014 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK425845/ )

The social determinants of health are the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks. Domains of the social determinants of health include economic stability, education access and quality, health care access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, and social and community context. (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. HP 2030 From https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health )

A system in which public policies, institutional practices, cultural representations, and other norms work in various, often reinforcing ways to perpetuate racial group inequity. It identifies dimensions of our history and culture that have allowed privileges associated with “whiteness” and disadvantages associated with “color” to endure and adapt over time. (Aspen Institute, 2016 From https://www.aspeninstitute.org/blog-posts/structural-racism-definition/ )

Environmental justice is the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies. (US EPA, 2023. From https://www.epa.gov/enforcement/environmental-justice-enforcement-and-compliance-assurance )