Main Body

8 Public health administration and infrastructure

Hector (Giovanni) Antunez

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, the learner will be able to

-

Learn about the importance of public health administration in the delivery of healthcare services

-

Learn about the structure of the public health infrastructure in the planning a delivery of health care in the U.S.

-

Identify the role of the different agencies involved in the planning and delivery of health care in the U.S.

-

Describe the importance of proper leadership in public health care administration.

-

Examine current events that apply to this chapter about public health administration

Introduction

The work in public health organizations cannot be accomplished without having leaders, managers, and administrators who are knowledgeable and experienced in planning, implementing, evaluating, monitoring, and managing material and human resources. It is impossible to image a public health system without those individuals who know how to fund, direct, and coordinate health services and additional elements such as health education and health policy.

The professionals exercising the mentioned functions above came from different professional backgrounds and training, some of them may have never done public health work, for example, civil engineers who need to work hand in hand with a trained public health individual who can coordinate the access to food for remote areas in a developing country, or, in a remote area in the same country.

It is with those who lack formal training in public health that everyday tasks are accomplished. And, for the trained public health workers they need to learn how to work with those individuals who know their job, but don’t know how public health works. This calls for the important task of increasing the number of trained public health workers through more schools of public health and informal training in the field.

Who are the managers and administrators in public health?

|

| “Health Care MBA,” image from Medium.com, licensed CC BY-SA 3.0 Deed. |

On one hand, many of the individuals mentioned above are the managers and administrators who work at the public health level within an organization or, office of public health, they are responsible for leading the organization, managing human resources and facilities, achieving goals and objectives set by the organizations they work. These managers and administrators are involved with addressing all six public health responsibilities and in additional programs such as chronic disease prevention and control, vaccinations, child and women health, adolescent’s health, etc., the staff and especially those trained public health professionals will guide their roles to provide them the technical assistance they may lack in public health.

On the other hand, many managers and administrators who probably have more expertise than others can also work with the 10 essential public health services as part of their responsibilities and will efficiently assist the public health professionals who lead the initiatives in those areas. At the same time, there are some areas that managers and administrators in public health must address, and this is called, ‘the public health practice profile for public health administration.’ The most common duties of a public health administrator include the following:

- Assessing community health issues

- Educating the public on common health issues, such as mental health issues and personal hygiene

- Developing public health plans to improve community health

- Setting budgets and writing grants for public outreach projects

- Hiring and training staff

Taken from ” What do public health administrators do?”[1]

Around the above major responsibilities, it is expected that public health administrators address the 10 essential public health services:

Examples

- Assess and monitor population health.

- Investigate, diagnose and address health hazards and root causes.

- Communicate effectively to inform and educate.

- Strengthen, support and mobilize communities and partnerships.

- Create, champion and implement policies, plans and laws.

- Utilize legal and regulatory actions.

- Enable equitable access.

- Build a diverse and skilled workforce.

- Improve and innovate through evaluation, research and quality improvement.

- Build and maintain a strong organizational infrastructure for public health.

From the APHA. ‘The 10 Essential Public Health Services’.[2]

Who are the public health administrators?

The most common positions held by health care administrators are health service manager, local health department (LHD) director, health officer, and public health emergency preparedness and response coordinator.

What are the duties of public health administrators?

Depending on their position, the most common duties in general follow:

Health Service Manager

A person in this position needs to be above all a leader, someone who can guide others, and who encourages following not because of the position but because of the leadership skills with the rest of the personnel under its responsibility. In general, a health services manager, directs, plans, analyzes, and coordinates public health efforts. Sometimes the position appears also as a health administrator in general. Either as a health service manager or, as a health administrator is usually the first to direct and assist in the planning efforts of its agency, and coordinate health efforts in general through the public health programs that provide regulatory services to the community. This person should also assist in identifying program priorities and the creation of new ones. [3]

The work of a health service manager

A health service manager is often responsible for directing or assisting in the overall planning as it has been mentioned before, its main responsibilities may be programs in chronic diseases such as cardiovascular and cancer; communicable disease prevention including vaccinations, and other areas of priority such as environmental health. Other areas in which a health service manager may also work in the maternal and child health program, adolescent health, family health, reproductive health, older adult health, health information, and informatics including epidemiology. All these mentioned positions are usually held by a specialist or, public health-trained coordinator but at the same time, all these mentioned areas require program management and decision-making duties that are handled by the health services manager who also provides authority, policy development, and implementation, assessment activities, budgeting and generation of official reports.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/health-services-manager-526024_Final-e78e05a34208402481e5d55acedd1b59.png) |

| “A Day in the life of a Health Service Manager,” image from Live About, Fair Use. |

Local public health agency director

A public health agency director usually works for a jurisdiction and has several functions that include the following: direction, management, supervision, planning, and other organizational activities for the jurisdiction. In terms of director, it directs the enforcement of the state and local public health laws and ordinances and also as a liaison with community organizations private and public, and it also directs staff that provides health education services. In addition, the public health agency director participates as a board member in the local board of health or a city or county board of supervisors. Overall, the public health agency director provides direction, especially in the administration of the human, fiscal (budgetary), and material resources of a local public health department.[4]

|

| “Health care workforce,” image from The National Governors Association, Fair Use. |

The health officer

This position is usually held by a physician and its major responsibilities are to direct, plan, organize, and medical oversight over public health programs for a jurisdiction. Also, the health officer provides technical consultation to staff and citizens, public officials, and community organizations. The medical oversight includes the supervision of the environmental health program, vital records, public health nursing, communicable diseases program, public health education, emergency and disaster planning, and state maternal and child services and programs. Although most persons in the position of health officer are physicians, in several cases the system allows non-physicians to act as health officers who are also program managers or directors of environmental health, health education, and other similar programs. [5]

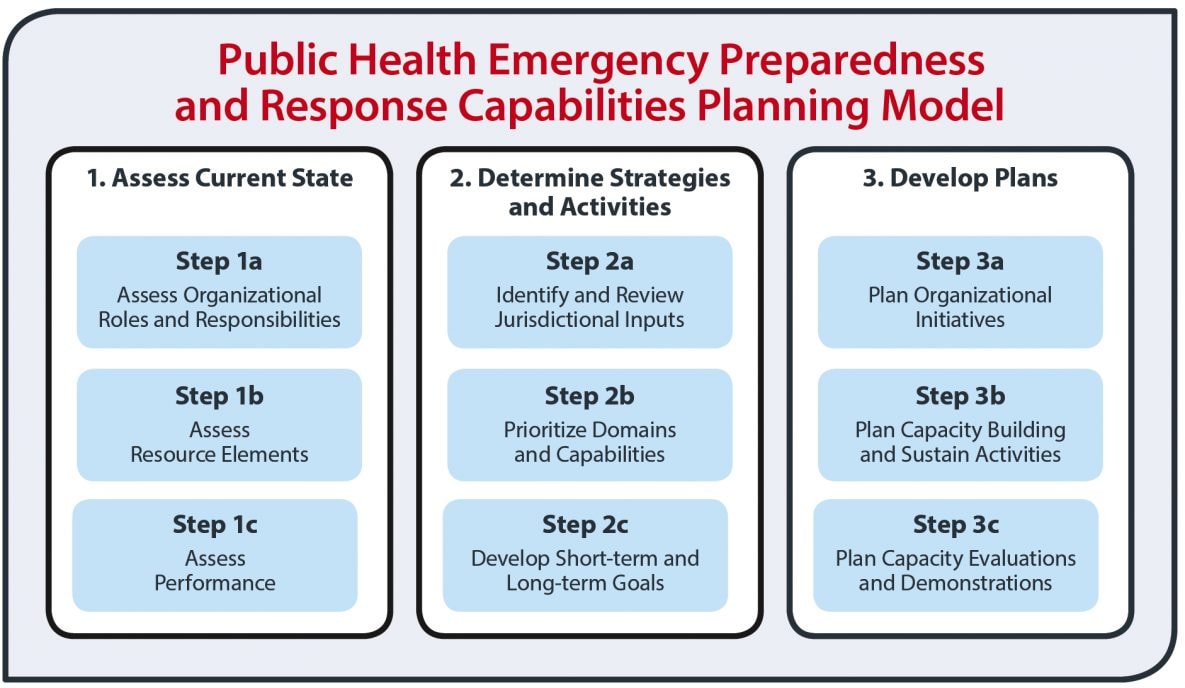

Public health emergency preparedness and response coordinator

This program officer as the name implies, is responsible for the planning, organization, and administration of emergency preparedness and response of the respective jurisdiction. These mentioned activities include pre-emergency planning, emergency response activities, and post-emergency functions during disaster mitigation.[6]

|

| “Public Health Preparedness Capabilities,” image from CDC, Public Domain. |

Career Prospects

Although the numbers change considerably year by year, it is reported that in 2021, the total number of Medical and health services managers was 712,528 people with many of them being women (72.2%), men represented only a relatively small number (27.8%); from these, the age of these workers varied considerably as the mentioned report presented, medical and health services managers workforce were 35 years and older. [7] The demand for medical and health services managers is high, with a high level of expectations that make the job a highly competitive one.

Where to find information about the training of medical and health services managers?

A very useful resource is the Association of University Programs in Health Administration (AUPHA), which provides information about careers in this area, but also information about undergraduate and graduate degree programs in health administration in the United States.[8] Another organization that provides important information about health administration is the Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Management Education (ACHESA) now known (it changed its name) as The Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Management Education (CAHME), which is the organization that accredits master’s level programs, and it is important to know that only CAHME accredited programs can become members of the AUPHA.[9]

Public health infrastructure

Now, the following section will cover some of the essential components of public health infrastructure. The content will intend to answer the following questions:

- What are the most important infrastructural components for public health departments at the state and local levels?

- How can these components be managed properly to optimize resources and improve the performance of public health organizations and systems?

In general, it is accepted that public health infrastructure consists of the resources and the relationships that are necessary to implement the public health core functions and essential services. In this context, what are those? They are the knowledge and technicalities of the field, health commodities and the institutional capacity of the local health departments. More on these three elements is presented below:

Knowledge in public health

In this context, what is “Knowledge”? Knowledge in public health refers to the education (formal or informal), training and foundational information about health among the public health workforce as well as the public. An example taken from the field of health literacy is that understanding prescription drug instructions, understanding doctor’s directions and consent forms, and the ability to navigate the complex healthcare system is “health knowledge”.[10] Another example can be the “knowledge” in the healthcare industry about Data/information. Issues related to integration/storage/management. Need for innovative analytic approaches. The ‘knowledge’ and experience that the healthcare worker has with data and health information also counts in terms of efficiency.[11]

Commodities

What are health commodities? According to an article from the United States Agency for International Aid and Development (USAID), “Health commodities include health products, health and medical supplies, and other items that may be needed for the provision of health services, including medicines, vaccines, medical supplies such as contraceptives dressings, needles and syringes, and laboratory/diagnostic consumables.” [12] These commodities also include the physical infrastructure, for example, buildings, equipment, and those additional resources available from the state and local health departments and its collaborators who want to also use their resources to the local public health efforts in their respective communities. In general, the lack of proper commodities makes it very difficult to deliver medical care and also implement public health programs and interventions in the community. [13]

Institutional capacity of the local health departments

This is the third characteristic of an infrastructure system in public health. Since the focus of this chapter is on the organizational management of the public health system, the content that follows will revolve around the institutional capacity of the local health departments and how it works. First, what is Institutional Capacity? The term “Institutional capacity” in a broad manner is the ability of an institution to achieve its stated goals. The definition of institutional capacity refers also to the following three things, the task function that the institution must have the ability to do, the resources (human, technical, and financial) , and the structures owned.[14] To better understand the institutional capacity, there is a need to review the most basic elements of the organizational aspects of the public health system, which is explained in more details in the content that follows:

Organizational Aspects of the Public Health System

In general it is accepted that the most basic organizational aspects of public health are: the leaders. Leadership is key element for success and collaboration. Who are these leaders? They are local individuals residing/or, who are part of a community (local leadership). How are they represented in the public health organizations/programs? These leaders are represented in what is known as Local, or, Community Boards of Health (CHBs).

Community Health Boards (CHBs) – The example of CHBs in Minnesota

The example used here is the CHBs in the state of Minnesota, the organizations of CHBs vary a little among states, and the example should help to understand the main elements of community health boards.

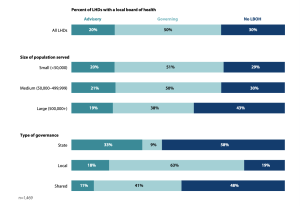

Who are the Community Health Boards (CHBs)? The Community health boards are the legal governing authority for local public health in the U.S. The CHBs work with the state (in this example, Minnesota) health department in partnership to prevent diseases, protect against environmental hazards, promote healthy behaviors and healthy communities, respond to disasters, ensure access to health services, and ensure an adequate local public health infrastructure. The following image shows some statistics of CHBs in the U.S

|

| “LHDs with a local board of health (LBOH) by size of the population served and type of governance,” Image from NACCHO 2019 National Profile of Local Health Departments, Chapter 2 Jurisdiction and Governance. [15] |

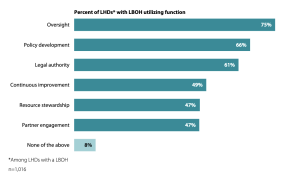

The following is an image that lists the main functions of Local Health Boards.

|

| “Functions that local boards of health (LBOH) utilize in a continuous basis,” Image from NACCHO 2019 National Profile of Local Health Departments, Chapter 2 Jurisdiction and Governance. [16] |

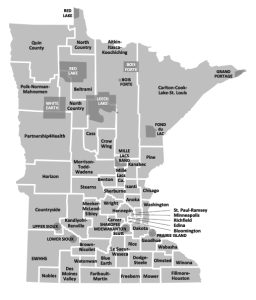

Brief history of the CHBs in Minnesota

Before 1977, over 2,100 local boards of health existed to serve Minnesota’s communities. In 1976 Community Health Services Act (now, the Local Public Health Act, or Minn. Stat. § 145A)[17] allowed boards of health to join and work as Community Health Boards, to serve a larger population and geographic area. The following image shows the CHBs by geographic area in Minnesota:[18]

|

| Map from Minnesota Dept. of Health. (n.d.). Minnesota Community Health Boards and Tribes.[19] |

What is the main responsibility of Community health boards (CHBs)?

Community health boards have statutory responsibility under the Local Public Health Act and must address and implement essential local public health activities. Additionally, community health boards must ensure that:

- A community health assessment and plan are completed on a regular cycle

- Community health needs are prioritized in a manner that involves community participation

- Needed public health services are developed and implemented[20]

The Local Public Health Act requires each community health board to serve a population of at least 30,000 people. If a single county doesn’t meet the population requirement, it can form a community health board with one or more neighboring counties. If a community health board serves three or more contiguous counties, the minimum population requirement does not apply.[21] In this context, the CHBs in Minnesota take many forms:

Community Health Boards Administration

Community health boards are required to have a community health services administrator and a medical consultant and may appoint an advisory committee. [22]The administrative system of CHBs requires funding that in a great majority of cases comes from grants and similar sources. [23]

Another element of community health boards is how members are elected, they are either elected themselves or appointed by elected officials. Due to local control and local investment of resources, the membership, composition, and business practices of community health boards vary throughout the state. This flexibility is a great strength of the state’s public health system; it helps ensure public health activities are aligned with community needs. [24] Over the past decade, several counties and community health boards have made changes to their public health organizational and governance structures, and more changes are being considered as local elected officials look for ways to address significant budget concerns, create efficiencies, and anticipate the retirements of public health leaders.

Organizational Aspects of the Public Health System

Another element of the Infrastructure in public health is the Coalitions and Consortia. Understanding this topic helps also to see the importance of community Health Partnerships. What is a coalition? According to Merriam-Webster, the following concepts are part of the concept, of the coalition: a temporary alliance of distinct parties, persons, or states for joint action. The act of coalescing: union. The act of coalescing : union.

|

| “No name”, image found in several places in the World Wide Web. Public domain. |

For example, “A multiparty coalition ruled the country.” [25] The definition from a public health perspective

|

| “Drug Free Communities”, image from ESD Prevention Services. Fair Use. |

•The goals that keep the coalition together range from information sharing to coordination of services,

Other Collaborative Organizations

- Advisory Committees

- Commissions

- Consortia and Alliances

- Networks

- Task Forces

Some more details about these types of committees is provided below:

Advisory Committees

This type of committee(s) generally responds to organizations or programs by providing suggestions and technical assistance.

Commissions

In general, commissions usually consist of citizens appointed by official bodies.

Consortia and Alliances

Consortia and Alliances tend to be semi-official, membership organizations. They typically have broad policy-oriented goals and may span large geographic areas. They usually consist of organizations and coalitions as opposed to individuals.

Networks

Networks are generally loose-knit groups formed primarily for the purpose of resource and information sharing.

Task Forces

Task forces most often come together to accomplish a specific series of activities, often at the request of an overseeing body.

Consortia vs Networks

It is very common for people to ask about the difference between consortia and networks. To answer this question, it is generally accepted that a Consortia is an ‘inside’ ‘coalition’ among partners, for example, a system, or a company, while Networks are coalitions ‘among’ organizations from different companies, or parties.

Partnerships

Partnerships are examples of ‘coalitions.’

What are coalitions necessary?

The main reason for which coalitions are necessary is because one reality, no single group acting alone can accomplish the many tasks required for changing the social, economic, and environmental conditions that impact health. Coalitions can achieve more widespread reach within a community than any single organization could attain.

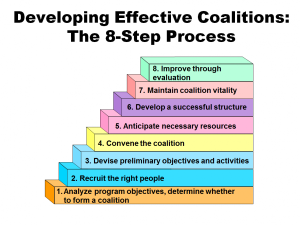

How do we build a coalition?

This is a frequently asked question: how do we build a coalition? One very useful model is the one proposed by the Prevention Institute manual, Developing Effective Coalitions: An Eight-Steps Guide,[30] which has been used here in this book to outline the process.

|

| “Developing Effective Coalitions”, image from the Prevention Institute, Fair Use. |

STEP 1 – Analyze the program’s objectives and determine whether to form a coalition.

STEP 2 – Recruit the right people.

STEP 3 – Devise a set of preliminary objectives and activities.

STEP 4 – Convene the coalition.

STEP 5 – Anticipate the necessary resources.

STEP 6 – Define elements of a successful coalition structure.

STEP 7 – Maintain coalition vitality.

STEP 8 – Make improvements through evaluation.

|

| “Possible Elements of a Community Team”, image from Healthy SD, Fair Use. |

As is seen above, the steps appear simple, but in practice, accomplishing them requires time. Also, some elements need more detailed information. One of these is the Roles within Coalitions – which is part of Step 6 (outlined above). The different roles within coalitions include the organization of the group, which requires basically, the following:

- The Chairperson

- The Facilitator

- Individual Member

- Lead Agency

- Member Organization

- Representatives

- Staffing and

- Steering Committee

Most specific details about each of the positions listed above follows:

The chairperson

The chairperson has the primary responsibility as spokesperson for the coalition. He or she may sign letters, testify in court, etc. on behalf of the coalition. The chairperson does not necessarily have to be from the lead agency. Frequently, the chairperson also acts as the facilitator.

The facilitator

The facilitator is responsible for running the coalition’s meetings. This person should be knowledgeable in group dynamics and comfortable with the task of including disparate members in group interactions, fostering group discussion, and resolving disagreements within the group. As with the chairperson, the facilitator does not necessarily have to be from the lead agency.

Individual members

The category ‘individual members’ refers to those people who do not represent a specific organization within the coalition but are interested in serving or volunteering in the work of the coalition. Another reason for individual members to join the coalition is personal or professional interest in the issue.

The lead agency

Member organization

This refers to those organizations that participate in coalition activities and send a designated representative to coalition meetings. In some coalitions, “member” is an official designation; some organizations may choose to become official members and others may participate on an ad hoc or informal basis.

Representatives

These are staff from member organizations who are selected to participate in the activities and meetings of the coalition. Ideally, these people have an interest in the problem, and their activities in the coalition comprise part of their regular job responsibilities.

Staffing

Staffing refers to the support functions necessary to make the coalition work (e.g., planning meetings, and preparing agendas). Staffing is typically a responsibility of the lead agency.

A steering committee

A steering committee is a small subgroup of the coalition that takes primary responsibility for the coalition’s overall direction. Typically, the steering committee will include the coalition chairperson and a representative from the lead agency. The steering committee may also include subcommittee chairpersons and representatives from other organizations that have a major commitment to the coalition’s objectives. Steering committees sometimes plan meetings and may provide decision-making between regular coalition meetings.

Additional steps

Additional steps that need that need additional remark is, Step 7, which is about the need to ‘Maintain coalition vitality.’ This is an important step that helps to sustain the life and duration of the coalition. Some ways in which vitality can be promoted is by going beyond the regular tasks and working more with the coalition members on their own personal and professional interests, spending time together in informal gatherings and for example, remembering their birthdays or special days.

One more remark

In addition, Step 8 also requires some remarks. The recommendation in this step is ‘Make improvements through evaluation’. This is an extremely important recommendation, because many times, the life of a coalition depends on the capacity to accomplish its goals, and report specific outcomes, the best way to track and report this is by evaluating the coalition’s efforts, including regular progress evaluation and an annual report.

So far, the following topics have been covered:

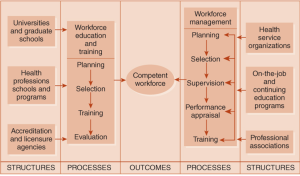

Human Resources Management in Public Health Departments

As an organization, public health departments need to pay attention to the management of its human resources. One important aspect of this is the workforce development. The education and training of public health workers should be a high-priority activity of public health departments because as more knowledge, training, and skills public health workers have the more efficient their work will be. These mentioned aspects can be seen as a system of inputs and outputs that result in a competent workforce.[31]

|

| Figure 7-3 Conceptual model for workforce development |

The training of public health professionals

The CDC recommends that public health agencies and organizations use competencies models to

- Develop job descriptions

- Assess knowledge and skills that contribute to job performance

- Identify critical gaps in training

- Create career paths

- Inform workforce development plans

- Support efforts to meet accreditation standards

The use of these competencies assures that the selected workforce not only will efficiently do the work but also, that this workforce will also develop their careers. In this manner, the work becomes a career and not just a job.[33]

The Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals

What are the ‘core competencies’? They are a set of knowledge and skills for the broad practice of public health that been developed by consensus, these have been defined by the 10 Essential Public Health Services. These competencies reflect foundational or crosscutting knowledge and skills for professionals engaging in the practice, education, and research of public health. They are the linkages between Academia and Public Health Practice.[34]

The Public Health Core Competencies are organized into eight domains, representing skill areas within public health, and three tiers, which describe different types of responsibilities within public health organizations.

The Eight Domains of the Public Health Competencies

As mentioned above, the Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals (Core Competencies) are organized into eight domains, that represent the skill areas within public health. For each domain, there are 4 and 13 competency statements. Also, these Core Competencies include three tiers, which describe different types of responsibilities within public health organizations. The tiers are used to organize the list of sub-competencies, which describes in a more detailed manner, the knowledge and skills for individuals with responsibilities related to each tier. That said, the eight domains of the public health competencies used to train and prepare the public health workforce in the United States are:

Each one of the competencies listed above is discussed in more detail as follows.

Data Analytics and Assessment Skills. Data Analytics and Assessment Skills focus on identifying, collecting, and understanding data; employing and evaluating rigorous methods for assessing needs and assets to address community health needs; and using evidence for decision-making to improve the health of communities.

Policy Development and Program Planning Skills. Policy Development and Program Planning Skills focus on developing, implementing, and evaluating policies, programs, and services; engaging in quality improvement for organizational and community planning; and influencing policies and programs to impact health and well-being for all.

Communication Skills. Communication Skills focus on employing effective communication strategies to convey information and combat misinformation and disinformation; assessing and addressing population literacy, language, and culture; soliciting and using community input; identifying opportunities to communicate data and information; communicating the roles of government, healthcare, and others; facilitating communications; and building trust with communities.

Health Equity Skills. Health Equity Skills focus on recognizing and responding to the diversity of the workforce and populations served; applying principles of ethics, diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice to policies and programs; committing to continuous self-reflection; re-evaluating organizational policies; and advocating to reduce systemic barriers that further health inequities.

Community Partnership Skills. Community Partnership Skills focus on understanding and developing relationships within the community; advancing collaboration while ensuring community power and ownership; defending public health policies, programs, and services; and evaluating effectiveness to improve community health and resilience.

Public Health Sciences Skills. Public Health Sciences Skills focus on using and contributing to the evidence base; understanding historical systems, policies, and events impacting public health; applying public health sciences to deliver the 10 Essential Public Health Services; critiquing and developing research; using evidence when developing policies and programs; and establishing cross-sector partnerships to improve the public’s health.

Management and Finance Skills. Management and Finance Skills focus on securing, managing, and engaging human and financial resources; supporting professional development and contingency planning to achieve program and organizational goals using principles of diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice; developing and defending budgets; motivating personnel; evaluating and improving program and organization performance; and establishing and using performance management systems to improve organization performance.

Leadership and Systems Thinking Skills. Leadership and Systems Thinking Skills focus on understanding and engaging with cross-sector partners and inter-related systems; creating opportunities for collaboration among public health, healthcare, and other organizations to improve the health of communities; building confidence and trust with staff, partners, and the public; identifying emerging needs; and developing a shared vision to engage with politicians, policymakers, and public health to advocate for the role of governmental public health.

The content above has been adapted from the overall content about ‘Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals,’ which is available online from the Public Health Foundation.[35]

Fiscal Management in Public Health

The ‘fiscal management’ refers to the financial resources available for Public health activities, which can be seen as both, inputs and outputs of the system that affect the outcomes and proper functioning of public health organizations and programs. Since fiscal management is a kind of investment approach, the organization invests/efforts, and then, it will have a gain, depending on the size of the efforts/investments. Gains require effort.

In general, the financial resources available for Public health activities also reflect the value that is put to any of the efforts/interventions through its programs. It is accepted that this value is based on several factors such as the following: the priority issues based on epidemiological reports, the political atmosphere of what is perceived as priority; the community needs assessments, and several other factors that are not always tangible.

Where does the public health money go? To what programs money is allocated?

Several factors (as it was mentioned before in another chapter) play a role when the allocations are done, but the process is highly political, which means, that politics are also in play when total budget allocations are done by legislators and political forces. But in general, the different budget allocations are based on the Essential Public Health Services (EPS) framework, but also on the need to maintain the workforce (human resources), the physical facilities, equipment, and other categories that don’t easily fit into any other of the categories.

|

| “Building a Healthy America,” Image from DHHS FY 2023 Report, page 1, Public domain. |

Information Management in Public Health

In addition to fiscal management and human resources, information and evidence is a key component of public health infrastructure. Information represents the scientific basis of public health making it also a priority area for functioning of the system and also for research and health care evidence-based services.

| The Six Principles of Public Health Information |

| 1. Recognize different types of data. |

| 2. Provide for integrated management. |

| 3. Maintain a service oriented. |

| 4. Ensure Flexibility. |

| 5. Achieve system compatibility. |

| 6. Protect confidentiality. |

| Adapted from Lumpkin J. R. (1995). Six principles of public health information. |

There is an immense amount of data and information needed to assess and address health problems. However, this data must be managed efficiently, especially in its collection, input, and analysis, so it becomes useful. [37]Also, the available data must be used effectively for public health practice and research. The data sets available need to be accurate and at the same time accessible for analysis and reporting. But how do we ensure the effective use of information sets in public health? Several principles underlie the effective use of information. Some of these principles include the classification of the type of data, its protection and confidentiality, its dissemination, system compatibility, and others. [38],[39] More details on these principles are presented in the content that follows.

| Encounter-based data |

Population-data |

|

•Describes population rather than individuals

•Usually collected from surveys, and environmental monitoring system

|

- It is not representative of the larger population

- It represents only individuals, who request services – it is group-specific

- It provides data duplicates – and individuals may request/use more than one service in the same institution, or system.

An additional principle for the management of public health information is, maintining a service orientation, this means, that for example a program for prenatal care may use it own information system, but the pregnant mother may also need to have access to nutritional programs that uses another system of information. But the important point here is that the mother who needs the service receives the needed care/services. Here, the needs of the client are put before the needs of the data system and its management.

Another important principle for the management of public health information is to ensure flexibility, this means that the system needs to be flexible enough to adapt to the different systems used by providers and at the same time recognize the limitations of managing information at the individual base level.

In the practice of public health, the principle of achieving system compatibility is very important because it allows data flow and functioning across systems although at the same time, is a risk for confidentiality of the information. Hence the importance of deidentificating of the information that is intended to be disseminated to researchers and the public in general. This takes us to the last principle of public health information mentioned here in this section of the book, the need to Protect confidentiality. Privacy issues constitute a special challenge for information systems, but federal and state status for the collection, sharing, and confidentiality of health statistics make it impossible for individuals to be identified.

- Coursera. (Aug 14, 2023). Public Health Administration: Definition, Jobs, Salaries, and More. From https://www.coursera.org/articles/public-health-administration ↵

- American Public Health Association (APHA). (n.d.). The 10 Essential Public Health Services. From https://www.apha.org/what-is-public-health/10-essential-public-health-services ↵

- Coursera. (Nov. 29, 2023). Medical and Health Services Managers: Duties, Pay, and More. From https://www.coursera.org/articles/medical-and-health-services-managers ↵

- Goodwin University. (n.d.). Public Health Directors, What does a public health director do? From https://www.goodwin.edu/glossary/public-health-director#:~:text=Public%20health%20directors%20organize%2C%20plan,with%20other%20public%20health%20professionals. ↵

- ZipRecruiter. (n.d.). What Is a Public Health Officer and How to Become One. From https://www.ziprecruiter.com/career/Public-Health-Officer/What-Is-How-to-Become ↵

- San Joaquin County Human Resources. (n.d.). Public Health Emergency Preparedness Coordinator (position announcement from the St Joaquin Valley Public Health Service. From https://jobapscloud.com/sjq/sup/Public%20Health%20Emergency%20Preparedness%20Coordinator%204-22-13.pdf ↵

- Data USA. (n.d.). Medical and Health Services Managers. From https://datausa.io/profile/soc/medical-health-services-managers#:~:text=Employed%20people-,The%20workforce%20of%20Medical%20%26%20health%20services%20managers%20in%202021%20was,44%20years%20(93%2C694%20people). ↵

- The Association of University Programs in Health Administration (AUPHA). (n.d.). Careers in Health Administration. From https://www.aupha.org/home ↵

- Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Management Education (CAHME). (n.d.). Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Management Education. From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commission_on_the_Accreditation_of_Healthcare_Management_Education ↵

- National Library of Medicine. (n.d.). An Introduction to Health Literacy, What Is Health Literacy? From https://www.nnlm.gov/guides/intro-health-literacy ↵

- KMS Lighthouse. (Nov. 25, 2029). Different Types of Knowledge in Healthcare. From https://kmslh.com/blog/different-types-of-knowledge-in-healthcare/ ↵

- USAID. (n.d.). Family Health International. Strategies for Expanded and Comprehensive Response (ECR) to a National HIV/AIDS Epidemic. Module 7‐Managing the Supply of Drugs and Commodities. From http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pnacn557.pdf ↵

- Agarwal, S., Tamrat, T., Fønhus, M. S., Henschke, N., Bergman, H., Mehl, G. L., Glenton, C., & Lewin, S. (2018). Tracking health commodity inventory and notifying stock levels via mobile devices.The Cochrane Systematic Review, 2018(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012907 ↵

- Bhagavan, M. & Virgin, Ivar. (2004). Generic Aspects of Institutional Capacity Development in Developing Countries. From https://mediamanager.sei.org/documents/Publications/Risk-livelihoods/SEI_Bhagavan_Institutional_Capacity_2004.pdf ↵

- National County of City Health Officials (NACCHO). (2019). 2019 National Profile of Local Health Departments. From https://www.naccho.org/uploads/downloadable-resources/Programs/Public-Health-Infrastructure/NACCHO_2019_Profile_final.pdf ↵

- National County of City Health Officials (NACCHO). (2019). 2019 National Profile of Local Health Departments. From https://www.naccho.org/uploads/downloadable-resources/Programs/Public-Health-Infrastructure/NACCHO_2019_Profile_final.pdf ↵

- Minnesota Dept. of Health. (n.d.). Summary of Minn. Stat. § 145A. From https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/practice/lphact/statute/docs/LPHActSummary.pdf ↵

- Minnesota Dept. of Health. (n.d.). Minnesota Community Health Boards and Tribes. From https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/practice/connect/findlph.html ↵

- Minnesota Dept. of Health. (n.d.). Minnesota Community Health Boards and Tribes. From https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/practice/connect/findlph.html ↵

- Berkowitz B. Collaboration for health improvement: models for state, community and academic partnerships. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 2000;6(1):67-72. From https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10724695/ ↵

- Minnesota Dept. of Health. (n.d.). Fiscal Management in Public Health, Minn. Stat. § 145A. From https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/practice/lphact/statute/index.html ↵

- Minnesota Dept. of Health. (n.d.). Medical Consultant for community health in Minnesota. From https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/practice/lphact/statute/docs/1102medicalconsultant_hb.pdf ↵

- Minnesota Dept. of Health. (n.d.). Major community health board funding sources in Minnesota. From https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/practice/lphact/lphgrant/docs/MajorFundingOverviewCHB.pdf ↵

- Varma, J.K. (Feb. 18, 2022). To make public health officials more accountable, they should be elected, not appointed. From https://www.statnews.com/2022/02/18/public-health-officials-should-be-elected-not-appointed/ ↵

- Merriam-Webster Online. (n.d.). Definition of Coalition. From https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/coalition ↵

- Marillac Mission Fund. (n.d.). Advocacy & Coalition-Building. From https://marillacmissionfund.org/what-we-fund/advocacy ↵

- Green L, Daniel M, Novick L. (2001). Partnerships and coalitions for community-based research. Public Health Reports, 116(1 Suppl):20-30. From https://www.researchgate.net/publication/11474553_Partnerships_and_Coalitions_for_Community-Based_Research ↵

- Nelson J, Rashid H, Galvin V, Essien J, Levine L. (1999). Public/private partners: key factors in creating a strategic alliance for community health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 16(3 Suppl):94-102. From https://www.ajpmonline.org/article/S0749-3797(99)00003-3/fulltext ↵

- [footnote]Prevention Institute. (n.d.). DEVELOPING EFFECTIVE COALITIONS: An Eight Step Guide. Pdf document. From www.preventioninstitute.org ↵

- Cohen, L., Baer, N., Satterwhite, P. (n.d.). DEVELOPING EFFECTIVE COALITIONS: An Eight-Step Guide. Prevention institute. From https://www.preventioninstitute.org/publications/developing-effective-coalitions-an-eight-step-guide ↵

- CDC. (n.d.). Public health workforce development. From https://www.cdc.gov/workforce/index.html ↵

- CDC. (n.d.). Training & Professional Development, Competencies for Public Health Professionals. From https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/professional/ ↵

- CDC. (n.d.). Competencies for Public Health Professionals. From https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/professional/competencies.html ↵

- Public Health Foundation (PHF). (n.d.). Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals. From https://www.phf.org/resourcestools/pages/core_public_health_competencies.aspx ↵

- Public Health Foundation (PHF). (n.d.). Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals: Domains. From https://www.phf.org/programs/corecompetencies/Pages/Core_Competencies_Domains.aspx ↵

- Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). (2023). Fiscal Year 2023, Budget in Brief. From https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/fy-2023-budget-in-brief.pdf ↵

- Forsee Medical (n.d.). Importance of data collection in healthcare. From https://www.foreseemed.com/importance-of-data-collection-in-healthcare ↵

- Pastorino, R., De Vito, C., Migliara, G., Glocker, K., Binenbaum, I., Ricciardi, W., & Boccia, S. (2019). Benefits and challenges of Big Data in healthcare: an overview of the European initiatives. European journal of public health, 29(Supplement_3), 23–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckz168 ↵

- Batko, K., & Ślęzak, A. (2022). The use of Big Data Analytics in healthcare. Journal of big data, 9(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-021-00553-4 ↵

- Questionpro. (n.d.). Population Data: Definition, Classification, Estimation and Importance. From https://www.questionpro.com/blog/population-data/ ↵

- L.A. Care Health Plan. (n.d.). Encounter Data. From https://www.lacare.org/providers/claims/submitting-encounter-data ↵

- David Koenig, D., Landrum-Hall, S., Kim, C. (Aug. 17, 2020). What’s the Matter with Encounter Data? Common Issues and Actionable State Strategies for Improving a Critical Data Resource. Presentation at the 35th Annual Conference of the National Association of Health Data Organizations. From https://www.nahdo.org/sites/default/files/2020-08/103-68%20Kevin%20McAvey%20What_s%20the%20Matter%20with%20Encounter%20Data__NAHDO%20Presentation_Aug%2016%202020.PDF ↵

- Christen, P. and Schnell, R. (2023). Thirty-three myths and misconceptions about population data: from data capture and processing to linkage, International Journal of Population Data Science, 8(1). DOI: 10.23889/ijpds.v8i1.2115 From https://ijpds.org/article/view/2115 ↵

the term refer the extent of the power to take public health decisions and judgments for an specific area (or jurisdiction), this area is usually a county served by the respective public health department.

it refers to an agreement among experts and public health practitioners that those elements outlined in the core competencies of public health are essential and practical in the training of public health workers.

no names, last names, home addresses, social security, or related personal information appears in the database, this practice helps to keep confidentiality.