42 Chords in SATB style

Samuel Brady

Key Takeaways

Music theorists sometimes simplify compositions into four parts (or voices) in order to make their harmonic content more readily accessible. This practice is called SATB style, abbreviated after the four common voice parts of a choir––soprano (S), alto (A), tenor (T), and bass (B).

When constructing a chord in strict SATB style, there are six rules musicians generally follow:

These six parameters form the basis of counterpoint and part writing, explored further in the sections Counterpoint and Galant Schemas and Diatonic Harmony, Tonicization, and Modulation.

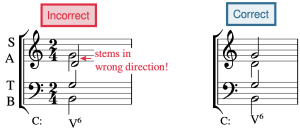

Stem Direction

On a grand staff in SATB style, the soprano and alto are written in the treble clef (upper staff), while the tenor and bass are written in the bass clef (lower staff). The soprano and tenor voices receive up-stems, while the alto and bass parts receive down-stems. If the stem direction is crossed, this is an error. Example 1 shows a chord with incorrect stemming, followed by the corrected version.

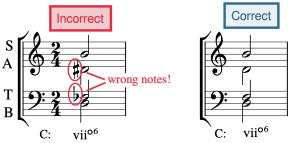

Chord Construction

Be sure to check each chord for correct notes and accidentals, and make sure that your chords are not missing any notes. In Example 2, the first chord has accidentals erroneously added to two of the pitches, which are removed in the second chord to create a correct B diminished triad in first inversion.

The bass voice must always correspond with the inversion that the Roman numeral’s figures indicate. However, the order of the upper notes can be arranged in many ways. In other words, there is not necessarily just one correct way to voice a chord.

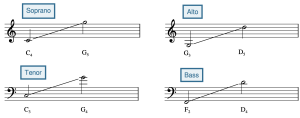

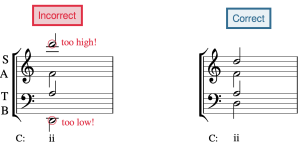

Range

There is a generally accepted range for each voice (Example 3):

- Soprano – C4 to G5

- Alto – G3 to D5

- Tenor – C3 to G4

- Bass – F2 to D4

In Example 4, the soprano and bass notes are out of range; this is corrected by moving the soprano note down by an octave and the bass note up by an octave.

Spacing

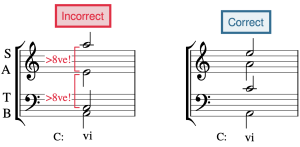

There should be no more than an octave between adjacent upper voices (soprano and alto, alto and tenor) and no more than a twelfth between the tenor and bass. The most common spacing error occurs between the alto and tenor because the notes appear in different clefs. Example 15 first shows a chord with incorrect spacing—the soprano and alto are more than an octave apart, as are the alto and tenor—followed by a corrected version:

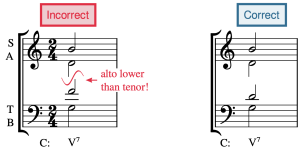

Voice Crossing

The ranges of voices should not cross. In other words, the soprano must always be higher than the alto, the alto must always be higher than the tenor, and the tenor must always be higher than the bass. In Example 6, the alto and tenor voices are crossed. This error is also the most common between the alto and tenor voices.

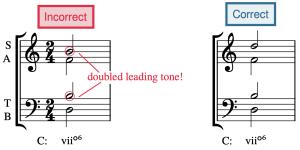

Doubling

In a triad, the note in the bass is usually doubled in an upper voice. However, there is an exception to this: the leading tone is never doubled. Other tendency tones, such as chordal sevenths, are also never doubled. Seventh chords don’t have any notes doubled because they contain four notes, one for each voice part. Incorrect doubling is seen in the first measure of Example 7, where the leading tone is doubled, followed by a corrected voicing in the second measure.

Coming soon!

A rhythmic or note value that does not fall on a beat (1, 2, 3, etc.).

Key Takeaways

In Western musical notation, pitches are designated by the first seven letters of the Latin alphabet: A, B, C, D, E, F, and G. After G these letter names repeat in a loop: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C, etc. This loop of letter names exists because musicians and music theorists today accept what is called octave equivalence, or the assumption that pitches separated by an octave should have the same letter name. More information about this concept can be found in the next chapter, The Keyboard and the Grand Staff.

This assumption varies with milieu. For example, some ancient Greek music theorists did not accept octave equivalence. These theorists used more than seven letters of the Greek alphabet to name pitches.[1]

Clefs and Ranges

The Notation of Notes, Clefs, and Ledger Lines chapter introduced four clefs: treble, bass, alto, and tenor. A clef indicates which pitches are assigned to the lines and spaces on a staff. In the next chapter, The Keyboard and the Grand Staff, we will see that having multiple clefs makes reading different ranges easier. The treble clef is typically used for higher voices and instruments, such as a flute, violin, trumpet, or soprano voice. The bass clef is usually utilized for lower voices and instruments, such as a bassoon, cello, trombone, or bass voice. The alto clef is primarily used for the viola, a mid-ranged instrument, while the tenor clef is sometimes employed in cello, bassoon, and trombone music (although the principal clef used for these instruments is the bass clef).

Each clef indicates how the lines and spaces of the staff correspond to pitch. Memorizing the patterns for each clef will help you read music written for different voices and instruments.

Reading Treble Clef

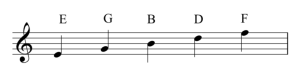

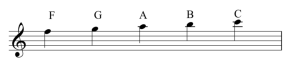

The treble clef is one of the most commonly used clefs today. Example 1 shows the letter names used for the lines of a staff when a treble clef is employed. One mnemonic device that may help you remember this order of letter names is "Every Good Bird Does Fly" (E, G, B, D, F). As seen in Example 1, the treble clef wraps around the G line (the second line from the bottom). For this reason, it is sometimes called the "G clef."

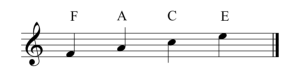

Example 2 shows the letter names used for the spaces of a staff with a treble clef. Remembering that these letter names spell the word "face" may make identifying these spaces easier.

Example 3 shows an octave treble clef. Notice the small "8" at the bottom of the clef:

An octave treble clef with an "8" at the bottom of the clef indicates that notes should be sung or played an octave lower than written. Music for tenor vocalists, guitarists, and bassists often uses the octave treble clef. A double treble clef also indicates that notes should be sung or played an octave lower than written, but it is much less common. Example 4 shows a double treble clef:

Sometimes music for piccolo or flute will use an octave treble clef with an "8" at the top of the clef. This indicates that notes should be played an octave higher than written. Example 5 shows this clef:

However, piccolo music is always assumed to sound an octave higher than written, regardless of which clef is used--a regular treble clef or an octave treble clef.

Reading Bass Clef

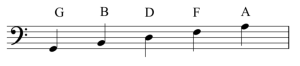

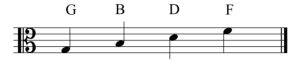

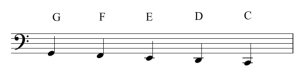

The other most commonly used clef today is the bass clef. Example 6 shows the letter names used for the lines of a staff when a bass clef is employed. A mnemonic device for this order of letter names is “Good Bikes Don’t Fall Apart” (G, B, D, F, A). The bass clef is sometimes called the “F clef”; as seen in Example 6, the dot of the bass clef begins on the F line (the second line from the top).

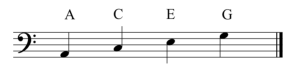

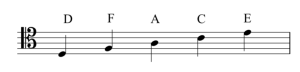

Example 7 shows the letter names used for the spaces of a staff with a bass clef. The mnemonic device "All Cows Eat Grass" (A, C, E, G) may make identifying these spaces easier.

Reading Alto Clef

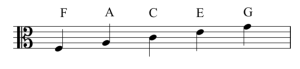

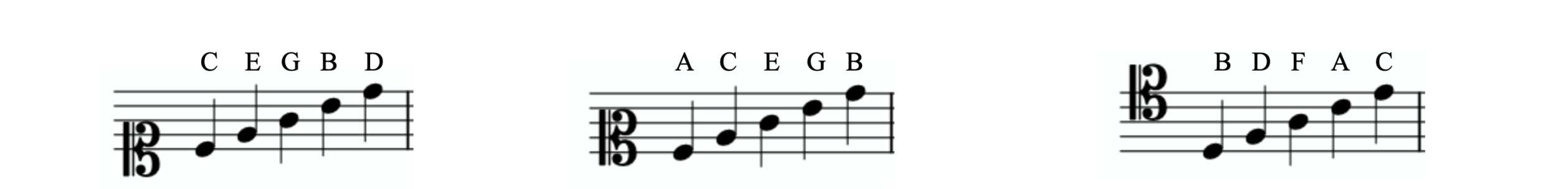

Example 8 shows the letter names used for the lines of the staff with the alto clef, which is less commonly used today. The mnemonic device “Fat Alley Cats Eat Garbage” (F, A, C, E, G) may help you remember this order of letter names. As seen in Example 8, the center of the alto clef is indented around the C line (the middle line). For this reason it is sometimes called a "C clef."

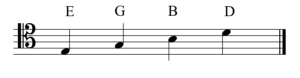

Example 9 shows the letter names used for the spaces of a staff with an alto clef, which can be remembered with the mnemonic device “Grand Boats Drift Flamboyantly” (G, B, D, F).

Reading Tenor Clef

The tenor clef, another less commonly used clef, is also sometimes called a “C clef,” but the center of the clef is indented around the second line from the top. Example 10 shows the letter names used for the lines of a staff when a tenor clef is employed, which can be remembered with the mnemonic device “Dodges, Fords, and Chevrolets Everywhere” (D, F, A, C, E):

Example 11 shows the letter names used for the spaces of a staff with a tenor clef. The mnemonic device "Elvis's Guitar Broke Down" (E, G, B, D) may make identifying these spaces easier.

You can practice identifying clefs in the following exercise:

Other C Clefs

The soprano clef], mezzo soprano clef, and baritone clef are also C clefs. These clefs are much less frequently used today, but they were common in the Renaissance period (1400–1600) (see Other Aspects of Notation for more information on stylistic periods). The center of each of these clefs is indented around the C line. Example 12 shows the letter names used for the lines of a staff with each of these clefs:

Ledger Lines

When notes are too high or low to be written on a staff, small lines are drawn to extend the staff. You may recall from the previous chapter that these extra lines are called ledger lines. Ledger lines can be used to extend a staff with any clef. Example 13 shows ledger lines above a staff with a treble clef:

Notice that each space and line above the staff gets a letter name with ledger lines, as if the staff were simply continuing upwards. The same is true for ledger lines below a staff, as shown in Example 14:

Notice that each space and line below the staff gets a letter name with ledger lines, as if the staff were simply continuing downwards.

Neutral Clef

A neutral clef is sometimes called a "percussion clef" because it is often used for percussion instruments with indefinite pitch. Example 15 shows a neutral clef on a staff:

In percussion clef, the lines and spaces of the staff do not represent letter names, but instead may represent different instruments. Neutral clefs are sometimes used on a single-line staff, as seen in Example 16:

- Gerou, Tom and Linda Lusk. 1996. Essential Dictionary of Music Notation. Los Angeles: Alfred.

- Gould, Elaine. 2011. Behind Bars: the Definitive Guide to Music Notation. London: Faber Music.

- Hiley, David. 2001. “Clef (i).” Grove Music Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.05927.

- Mathiesen, Thomas J. 2014. "Greek Music Theory." In The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory, ed. Thomas Christensen. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- McGrain, Mark. 1986. Music Notation. Boston: Berklee Press.

- Roemer, Clinton. 1985. The Art of Music Copying: The Preparation of Music for Performance, 2nd edition. Sherman Oaks: Roerick Music Company.

- The Staff, Clefs, and Ledger Lines (musictheory.net)

- Timed Game: Flashcards for Treble, Bass, Alto, and Tenor Clefs (Richman Music School)

- Printable Treble Clef Flash Cards (Samuel Stokes Music) (pages 3 to 5)

- Printable Bass Clef Flash Cards (Samuel Stokes Music) (pages 1 to 3)

- Printable Alto Clef Flash Cards (Samuel Stokes Music)

- Printable Tenor Clef Flash Cards (Samuel Stokes Music)

- Paced Game: Treble Clef (Tone Savvy)

- Paced Game: Bass Clef (Tone Savvy)

- Paced Game: Alto Clef (Tone Savvy)

- Paced Game: Tenor Clef (Tone Savvy)

Easy

More Advanced

- Treble Clef Only (.pdf)

- Treble Clef with Ledger Lines (.pdf)

- Worksheets in Bass Clef (.pdf)

- Bass Clef with Ledger Lines (.pdf)

- Mixed Treble and Bass Clefs (.pdf)

- Worksheets in Alto Clef (.pdf)

- Worksheets in Tenor Clef (.pdf)

- Writing and Identifying Notes Assignment #1 (.pdf, .mscz). Asks students to write and identify notes in treble, bass, alto, and tenor clefs, with and without ledger lines.

- Writing and Identifying Notes Assignment #2 (.pdf, .mscz). Asks students to write and identify notes in treble, bass, alto, and tenor clefs, with and without ledger lines.

- Pitch Notation (.pdf, .mscz). Asks students to write and identify notes in treble and bass clefs only, with and without ledger lines.

A variation on the 12-bar blues progression. Typically composed of four four-bar phrases, usually two iterations of tonic, followed by subdominant and dominant. The final phrase may or may not end with a turnaround.