1 Ch. 1 What is Crime?

Jeff Bry and Brandon Hamann

Criminology and Crime

Nature of Crime and Deviance

Introduction

What is crime? Crime is a phenomenon most people find compelling, however most possibly repugnant and disconcerting. To understand crime, one must understand social norms. Social norms are the behaviors and standards that are “acceptable” in society. Social norms are taught and learned at the societal level, they are taught in a variety of ways and in a variety of societal levels (interpersonally, peer groups, parents, television, etc.).

Violations of social norms are generally minor, receiving minor responses from others. An example of a violation of a social norm may be a young child picking his or her nose. As they are doing so, their parents, siblings or other people around the child may admonish them for this behavior; telling them it is “gross”, “rude” or inappropriate. By learning about social norms one becomes able to predict which behaviors are acceptable and which may receive a negative consequence. As social norms are learned, the perspective of socialization also becomes important. Socialization refers to the term sociologists use to describe life-long learning for humans. We are socialized from birth until death, being shown and told about the environment and world around us. For example, in some cultures people are taught to eat their meals with their hands, in other cultures eating with your hands is taboo. Learning by watching others, also by being told what is appropriate or inappropriate is how we develop as human beings.

As we are taught social norms, we learn some behaviors that may be viewed as deviant. Deviant behaviors are behaviors that violate social norms, although not all violations of social norms will necessarily be considered deviant. The example of a young child picking his or her nose may be excused because of their age; the same act by a teenager or adult may be viewed as deviant. Underage drinking may be viewed as deviant by many adults, but it may be accepted by many teenagers and those young adults who are not quite of legal drinking age. In much of the world prostitution is viewed as deviant, but it is not illegal in all nations or even states in the United States.

Some social norms become more substantial as things one should not do, for example taking someone else’s property, drinking and driving, or extreme cases such as murder. While these behaviors may be viewed negatively as norms, they are examples of behaviors that have evolved in society to be criminalized. The process of criminalizing something essentially makes the act illegal in that society. What is criminalized with vary from nation to nation, even state to state in the United States. While recreational marijuana may be legal in the state of Minnesota, it is illegal in the states of North Dakota and Wisconsin. As these states share a border, this may cause concern/issues as a substance may be viewed and responded to very differently in each state.

Picture Sourced from pixabay https://pixabay.com/vectors/search/

As behavior becomes criminalized, we shift in focus from social norms to crime. A crime is an act that violates a legal statute or statutory law. Statues are a formal written response by a legal authority, such as a state legislature or the United States Congress. Statutory law is the actual language of a law written by a governing body with the power to make and enforce a law. Crime and deviance are related but are very different terms. A crime is a violation of a law, deviance is a violation of a social norm. While a person who commits crimes will more than likely be viewed as deviant, violating most social norms is not necessarily a crime.

Picture souce pixabay.com

In a Student’s Own Words:

Question: What is crime? How would you describe crime, how much an issue/problem is crime?

“So, I like the sociological perspective of separating out law and anti-social behavior, and I personally tend to think about crime in a more philosophical sense than purely legal one, which is largely why am taking criminology instead of criminal justice—I didn’t want to take the theoretical underpinnings of crime for granted. I believe, as well, that a large portion of what is deemed “criminal” in the United States, is political as well: mandatory minimums and petty drug laws supplying laborers for the prison industrial complex, for example.”

What is Criminology?

Criminology is the study and scientific pursuit of the nature, extent, cause and control of criminal behavior. Criminology is a diverse, multi-discipline approach to understanding the nature of crime. Criminal behavior is a complex term, it may evolve and change as society and social norms change. An example of work a Criminologist may conduct includes researching change in offending behavior after some societal or legal action or change. For example, have certain crimes increased or decreased as marijuana has been legalized in certain states? Or have there been increases in drunk driving and assault cases as certain municipalities have extended bar closure times from 1 am to 2 am? Or do states that allow open carry or conceal and carry gun laws have more accidental shootings? More murders by guns? Is our criminal justice system biased against the poor, against racial and ethnic minorities? These and a multitude of other questions and issues are examined and addressed by Criminologists.

Social and Public Policy are programs or plans generally enacted by a government, to address and/or alleviate problems in society. There are a variety of social and public policy programs designed to address or reduce a social problem. For example, homelessness is a chronic problem facing our society. Drug use and abuse is a chronic problem facing our society. Crime is a chronic problem facing our society. As decision makers deal with the consequences of a variety of social problems, social and public policy steps are taken to address those issues. Examples include the “War on Drugs”, “War on Terrorism” and a variety of programmatic and policy steps that are designed to reduce (or address) some issue in society.

Criminology as Theory

One important aspect of criminology is criminological theory. Criminologists produce and conduct research from a theoretical perspective. Theory is a clearly stated proposition that identifies and posits relationships in a causal manner regarding events and aspects under study. What this means in real world terms varies, but generally theory is conducted to better understand phenomena in the natural world.

The study of human beings is very complex; people may be somewhat predictable but generally not as straight forward to study as other items in the natural world. Water boils at a temperature of 212 degrees Fahrenheit, water freezes at a temperature of 32 degrees Fahrenheit, this happens consistently in the natural world. People are not this consistent, what may motivate one person’s behavior may or may not motivate other people’s behavior. As an example, I am fearful of snakes. If someone brought a large snake into my presence, I would be fearful and recoil as it was brought closer to me. Other people would respond in a similar way to me, but many would be happy to see the snake, perhaps even want to handle/hold the snake! This is a simple (and somewhat silly) example, but it demonstrates issues with prediction of behavior in people. Guessing who is or is not afraid of snakes would be difficult, although one could ask people how they feel about snakes and how they would respond to interactions with snakes.

Many criminologists search for a general theory to explain crime and criminal behavior. General theories are theories that can be applied to large swaths of society/humanity and are generalized regarding crime. As human behavior and responses are difficult to predict, a general theory of crime seems to be a challenging undertaking. However various theorists attempt to identify some general characteristics that results in higher risk of crime. An example is Gottfredson and Hirchi’s Low Self-Control Theory (1990), which takes the perspective that people with low self-control commit more crime because of a master trait of low self-control. This theory is often referred to as the general theory of crime, as it approaches crime from a master trait or characteristic that increases the probability of crime.

One other approach to theory is to integrate theory. Integrated theories are argued to be more complete, as theorists take a multi-disciplinary approach to studying behavior and specifically crime. In opposition to a general theory, integrated theories attempt to blend or incorporate a variety of approaches or disciplines into their study. For example, a promising area in the study of crime is a biological approach to crime. Researching how genetics, neurotransmitter functioning, brain development etc. may affect aspects of behavior and crime. One other promising area includes developmental psychology approaches, especially prenatally and in early development to predict behavior and possibly future crime. Sociological theories have long been dominant in criminology, having good explanatory power regarding crime and behavior. The issue with integrated theories is to blend or integrate each of these distinct disciplines and approaches into one clearly defined and designed theory. As you can imagine this is difficult, especially blending all the different approaches and variables one must consider. Integration of theory seems to be a promising approach to criminological theory.

Schools of Criminology

Criminology is housed in two primary schools, the Classical School and the Positivist School. The positivist school branches out to into the Chicago School and Conflict Criminology.

The Classical School (18th Century) is the earlier of the two schools, founding fathers include Jeremy Bentham and Cesare Beccaria. The philosophy of the Classical School includes the perspective of rationality in terms of crime and punishments. From a Classical School perspective, people (including offenders) are rational players that make decisions based upon pain and pleasure principles. The Classical School also takes a position of utilitarianism, or the assumption that people respond better to fairness, equity and balance. If the punishment for a crime is excessive and/or is too severe for the crime committed, people will not accept that punishment or that law. In that perspective, putting someone to death for speeding would more than likely seem very excessive to most people, so people would not see the utility in that law. Giving someone a ticket and a fine for speeding may be reasonable, certainly more reasonable than giving someone the death penalty.

Classical theorists take the position that crime control occurs when the penalty for crime makes crime unreasonable, or by minimizing the reward for completing a crime. If you make an item more difficult to take or steal or minimize the reward or gain for taking the item, this approach should reduce crime. Classical School also takes the position of free will, or the belief that people have the freedom to make a choice regarding situations. An example of free will is the perspective of deterrence. Deterrence is the perspective that people will not commit an act because the risk is too great, or the reward is too low. A modern-day example of deterrence may be drinking and driving. As drinking and driving laws and sanctions have become more strict and severe, less people (potentially) make the choice to drink and drive. It is far more common for young people today to take a taxi or Uber when they are out consuming alcohol, arguably because of the potential consequences of getting caught drinking and driving.

The Positivist School takes the position that crime can be studied and “solved” using the scientific method. So, in essence, positivism takes the position that crime is something to be studied, much like any other phenomenon in the natural world. The Positivist School takes two approaches to crime:

Human behavior is a function of internal and external forces (such as war, famine, social class, wealth, biological, environmental, psychological).

Use of the scientific method to solve social problems. Utilization of research methods, hypothesis testing, etc. Problems can be examined and addressed using empirical research.

Early Positivist School research was not very scientific, valid or empirically sound. They are mentioned and discussed as examples of where we have come versus where we are going as a discipline. Early approaches to the Positivist School include:

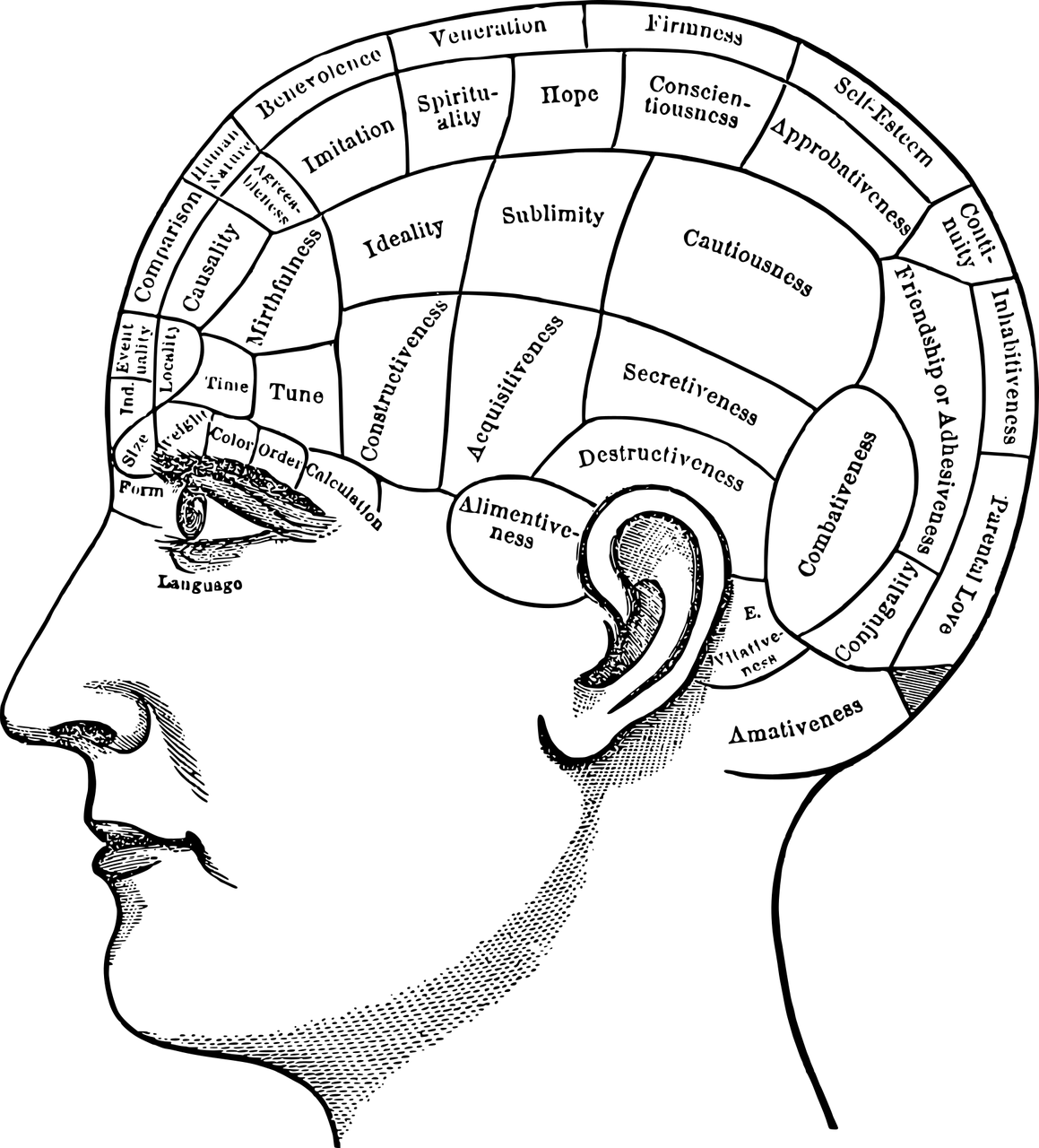

Physiognomists: The study of facial features of criminals to determine if their facial features lead to antisocial/criminal behavior. Examples include distance between nose, eyes, ears, etc.

Phrenologists: The study of the human skull, including bumps and indentations in the skull. Meaning was derived from these bumps and indentations, perception that there was behavioral meaning in these bumps and indentations.

0

Picture source pixabay https://pixabay.com/vectors/search/

Both of these early Positivist School attempts were discredited, especially as the biological sciences improved in explanatory power and consistency. However, people may still assume there is “something” to each of these approaches, they have been soundly discredited by modern science.

Biological Determinism (Cesare Lombroso) is a concept utilized by Lombroso and others to determine who may be a criminal. Lombroso was a medical doctor, he completed research on cadavers of executed criminals and of people who were mentally ill. He came to believe these people were “atavists”, or biological throwbacks in human evolution. These atavists were more “animal like” than other humans, they were also Born Criminals in Lombroso’s estimation. This assumption led Lombroso to believe criminality and mental illness was inherited, especially since these atavists were less intelligent and more impulsive and aggressive than non-Atavist humans.

The claims of Lombroso (and others) are no longer taken very seriously, especially the perspective that all humans are not equally and/or biologically the same. Modern criminologists also point out the potential racial and ethnic discrimination that may result from perspectives of atavism. Disciplines such as sociology have been utilized to demonstrate the power of the environment and social structure versus individual biology.

Social Positivism or more commonly known as the Sociological Perspective began to gain power in the mid 1700’s to late 1800’s. This was during a time of great population increase, growth of cities and examinations of social problems that arose from these changes. As cities such as Paris, London, New York and Philadelphia began to industrialize and grow, there were new issues to address as towns turned into large cities.

Early contributors to social positivism include Adolphe Quetelet, who began the Cartographic school of criminology. He used basic and rudimentary statistics to uncover trends in crime, many of which are still examined today. For example, seasons of the year, climate, population and the poverty level of a neighborhood may be predictors of an increase or decrease in crime. There are generally increases in certain types of crime during warmer or colder seasons, also crime tends to increase as population of a city or town increases.

Emile Durkheim is a substantial contributor to the field of sociology, he also made contributions to the study of crime and criminal behavior. Durkheim believed crime is a normal phenomenon, crime has always existed since the beginning of civilization. As people began to live in close proximity, some people would potentially victimize other people. Durkheim felt there would always be something considered a “crime”, as society grows and evolved different behaviors may be viewed as criminal. Durkheim also argued people’s differing “wants and need” created opportunities for crime. He also believed crime may bring out needed change in society (civil and women’s rights movements) and may also demonstrate the “Ills” or problems in a society.

The Chicago School (Park and Burgess) started a new perspective on studying crime in society. The Chicago School concentrated on urbanization and so called “natural influences” which may increase or decrease crime in certain areas of a city. Proponents of The Chicago School believed crime is a function of neighborhoods and environments, not about the individuals living in those neighborhoods and environments. Below is a piece on The Chicago School and social ecology perspectives from Brandon Hamonn’s Criminal Justice textbook. https://louis.pressbooks.pub/criminaljustice/chapter/2-7-the-chicago-school-of-criminological-theory/

The Biological Positivists looked at criminality through the lens of scientific experimentation, attempting to explain causation through physical traits. The Psychological Positivists tried to explain criminality as a product of mental illness and looked at individual and group personality traits as possible causes. The Chicago School, however, took things to a different level. They saw criminal behavior as a product of one’s environment, developing the concept of human ecology – the study of the relationship between humans and their environment. The Chicago School was so named because the theorists who produced the groundbreaking research into how humans interacted with their surroundings and how that interaction affected behavior came from the University of Chicago in the 1920s and 1930s (Fedorek, 2019).

Figure 2.7: Dr. Robert E. Park

Figure 2.7: Dr. Robert E. Park

Robert E. Park[1] (1864-1944), an American urban sociologist, spent his professional career studying human behavior as it pertained to human ecology, race relations, assimilation, migratory patterns, and social structure. Along with his colleagues, noted sociologists Ernest W. Burgess, and R. D. McKenzie, Robert Park published the book The City (1925), which conceptualized a city much like a living organism, with interactions between humans and their natural environments acting in both a shared and conflicting manner depending on where a group lived within the city.

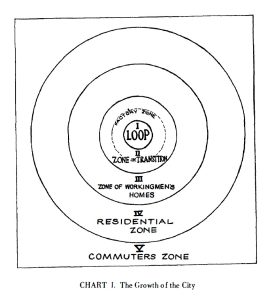

It was Burgess, however, who proposed the Concentric Zone Theory, which stated that a city’s design was conducive to criminal behavior within its “Zone of Transition” between the areas where people worked and where they lived (Burgess, 1925). In simpler terms, a city could be seen much like a target board, with multiple concentric circles surrounding a central hub (see Figure 2.8). Each inner and outer circle was specific to its municipal function (manufacturing, city business, residential, etc.).

Figure 3.8: Burgess’s Concentric Zone Model Source: Burgess, E. W. (1925). The Growth of the City: An Introduction to a Research Project. In R. E. Park, E. W. Burgess, & R. D. McKenzie, The City (pp. 47-62). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Figure 3.8: Burgess’s Concentric Zone Model Source: Burgess, E. W. (1925). The Growth of the City: An Introduction to a Research Project. In R. E. Park, E. W. Burgess, & R. D. McKenzie, The City (pp. 47-62). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Two students of Burgess and Park at the University of Chicago expanded on the concept of the Concentric Zone Model and developed their own theory. Clifford Shaw and Henry McKay (1942) noticed that within the different zones of transition, there were inequalities between them. Some had infrastructure that was in disrepair, some had differing demographics, and some had socioeconomic differences (Fedorek, 2019). What all this meant was that not every residential zone was the same, had the same type of people living in them, or had the same level of income, education, or employment opportunities. Those zones that were more educated, had higher levels of income, and fewer buildings in bad shape, were more organized than those zones with less educated people of color, higher unemployment, lower income, and more “broken windows” (more on this later).

What does all this have to do with crime? According to Shaw and McKay, a great deal. If one community is experiencing a high level of “social disorganization” due to inequalities experienced because of low employment, or low education opportunities, or even the inability to communicate within its own neighborhoods because the population is unable to understand each other, then there can theoretically be a higher chance for criminality within that specific zone of transition. Likewise, the opposite is also theoretically true: If a zone of transition is highly organized, the population is cohesive and stable with higher levels of income, education, and a low unemployment rate, the chances of there being a high crime rate is relatively low.

Figure 2.9: Dr. Edwin Sutherland

Figure 2.9: Dr. Edwin Sutherland

Dr. Edwin Sutherland[2] (1883-1950) was an American Sociologist considered to be one of the most influential criminologists of his time. He is credited with the development and definition of Differential Association Theory of Criminality and coined the term “White-Collar Crime” in 1939. Dr. Sutherland earned his PhD in Sociology from the University of Chicago in 1913 and went on to establish the Bloomington School of Criminology at Indiana University. According to Dr. Sutherland’s Differential Association Theory, criminality was a learned behavior, commonly brought on by groups of individuals who had splintered from the main group and had deviated in their behaviors from the accepted norms (see Section 2.10.3 for further analysis). Sutherland also was instrumental in combating the established notion that criminal behavior was relegated to only the poor and lower class of society. He famously theorized that the upper classes were more than capable of criminal behavior and were not immune to the deviance of criminality just because of their social status. Furthermore, Dr. Sutherland’s “White-Collar Crime” theory purported that businesses frequently engaged in criminal activity for the benefit of their practice as an expression of their business (Sutherland, 1940).

Robert E. Park (1864-1944) – American urban sociologist who studied human ecology. ↵

Dr. Edwin Sutherland (1883-1950) – American Sociologist who is credited with the development of Differential Association Theory and “White-Collar Crime” theory. ↵

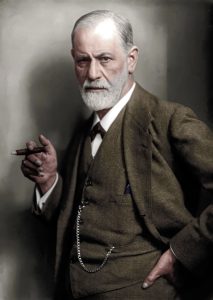

Psychological Positivism examines the psychological aspects of crime and criminal behavior. Early pioneers include Sigmund Freud who examined behavior from the perspective of psychoanalysis. Freud proposed that maladjustments in the individual psychological state may stem from personal experiences, especially during childhood. Freud also argued that criminal behavior was a form of mental illness. https://louis.pressbooks.pub/criminaljustice/chapter/2-6-the-positivist-school-of-criminological-theory/

Figure 2.5: Dr. Sigmund Freud (1856-1939)

Best known for his work in the psychological field of personality disorders, Austrian neurologist and psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud[3] (1856-1939) postulated that the human mind was separated into three distinct psychoanalytical types: the Id, the Ego, and the Superego. Through his studies, Freud theorized that criminal behavior was a product of mental illness, motivated by unconscious psychosexual conflict (Fitzpatrick, 1976). The Id, according to Freud, was the part of the human mind that controlled basic animalistic urges (fear, anger, compulsion, etc.) and was the most basic and earliest to develop, usually in childhood. The Ego helped to control the Id and began to mature as the child matured and learned from its surroundings and its parents what was good behavior and what was bad behavior. The Superego kept everything from going bonkers, hopefully.

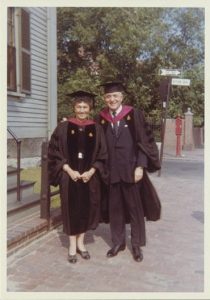

Figure 2.6: Drs. Sheldon and Eleanor Glueck

Then there were those who wanted to study personality traits of criminals. Sheldon and Eleanor Glueck[4] (1950), Polish-American criminologists, determined that there was no such thing as a criminal personality, but that there were some personality traits that were clustered together (Fedorek, 2019). Their work included a longitudinal study – a type of experiment that takes a long time to complete, usually decades – of 1000 teenage juvenile delinquent and non-delinquent boys to try and understand the causes of criminal behavior in youths. Their findings resulted in no explanations as to the causation of delinquent behavior. However, there were correlations in certain personality types and criminal behavior: low self-control, low empathy, and an inability to learn from punishment (Fedorek, 2019).

Charles Darwin (1809-1882) – British naturalist who is considered the founder of evolutionary science. ↵

Cesare Lombroso (1835-1909) – Italian phrenologist, physician, and founder of the Italian School of Criminology. ↵

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) – Austrian neurologist who developed psychoanalysis. ↵

Sheldon and Eleanor Glueck – Polish-American criminologists who studied personality traits in criminals. ↵

Conflict Criminology developed out of the writings of Karl Marx. Karl Marx didn’t discuss crime in substantial detail, but he was fairly clear crime is result of oppressive labor conditions, alienation and misery resulting from capitalism. Marx argued capitalism and the concentration on economics created conflict in society, as what is good for the owner is generally not good for the workers. Workers and owners are in a state of class conflict according to Marx, which in a capitalist system generally benefits the owners (capitalists).

Viewpoints of Crime

There are competing perspectives or viewpoints of crime in the fields of criminal justice and criminology. Each of these perspectives views and treats crime a bit differently, with different perspectives on causation, responses and so forth. We will discuss each of these viewpoints of crime.

The Consensus View of Crime views crime as acts that are viewed negatively to most people in society. From this perspective, substantive criminal law (written law) is created to define what is a crime and what the sanctions will be for specific crimes. These laws should reflect the wants and needs of society; however not all laws will be agreed upon or accepted by all groups in society.

The Conflict View of Crime views crime and criminal law as being created to protect the interests of the wealthy and powerful. From this perspective, the law and development of crime is created to protect and advance the interests of societies elite and to advance their social status. The law protects the “haves” from the “have-nots”, the law and criminal justice system is generally viewed as targeting the lower classes.

The Interactionists View of Crime uses the sociological concepts of Symbolic Interactionism to describe and explain the law and crime. From this perspective people will act and react in accordance with their perception of reality and meaning. People observe the manner in which people react to behaviors and learn to interpret symbols and meanings. For example, underage drinking is an offense, but it is viewed as normal to most people and is supported by teenagers and college age students. On the other hand, sex offenders (even minor sex offenders) are assigned a label that may make life more difficult for them in terms of finding employment, a place to live, acceptance by others and so forth. The labels assigned to people may matter depending on what they are caught doing, but also whether or not they get caught in the first place. Symbolic interactionists would also argue crime has no meaning UNLESS meaning is assigned to the behavior.

Summary

As you can see from Ch. 1, criminology is a complex and detailed discipline with many parts working together. There are many aspects of criminology to discuss and share, including research, the legal system, nature and extent of crime, theory and prevention and treatment. We will discuss these topics and others through the accompanying chapters.

References

2.6 The Positivist School of Criminological Theory Copyright © 2024 by Brandon Hamann is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

2.7 The Chicago School of Criminological Theory Copyright © 2024 by Brandon Hamann is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Durkheim, Émile. The Division of Labor in Society. Translated by W. D. Halls, Free Press, 1984.

Durkheim, Émile. Rules of Sociological Method. Translated by W. D. Halls, Free Press, 1982.

Gottfredson, M. R., & Hirschi, T. (1990). A General Theory of Crime. Stanford University Press.

Lombroso, Cesare. Criminal Man. Translated by Mary Gibson and Nicole Hahn Rafter, Duke University Press, 2006.