7 Ch. 7 Social Process Theories

Dr. Sean Ashley; Curt Sobolewski; Dr. Zachary Rowan; Brandon Hamann; and Jeff Bry

Ch. 7

Social Process Theories

Introduction

In this chapter we will discuss various social process theories of crime. In this discussion, we will examine various aspects of social process, including interaction, labeling, associations and learning. Social process theories view treatment by and responses of key others (family, peers, teachers, etc.) may greatly effect behavior. Role models, peer pressure and family input (among other influences) may greatly shape individual behavior, also insulate people against or push people towards crime.

Social Process Theories

Social Structure does not explain everything, why do people in bad neighborhoods NOT commit crime? The perspective of social process broadens the discussion of potential causes of crime, especially compared to social structure crimes alone. For example:

–Disorder, poverty, neighborhood decay, etc. alone do not explain all crime.

-Discussion of socialization using Social Process Theories to more adequately attempt to explain crime.

-Social-Psychological approach. Matter of individual socialization coupled with the interactions people experience socially.

-May be influenced by family, friends, peers, educational experiences, etc.

-Interactions with teachers, police, employers, other authority figures.

-Positive or Negative experiences affect outcomes.

Symbolic Interactionism

Interactionist Theories

Interactionist theories are theories that suggest that criminal behavior is learned through interaction with others. Socialization and learning processes occur as the result of group membership and relationships. In other words, the saying “you are known by the company you keep” fits perfectly with the interactionist perspective because it is the company you keep that may determine your attitudes and subsequent behaviors.

An area of the interaction perspective is the dramaturgical perspective. Irving Goffman (1959) states the dramaturgical perspective is about roles an individual plays (mother, father, teacher, dentist, etc.) and the attempts people make regarding something he referred to as impression management. Goffman saw people as “actors” on a stage, playing certain roles and providing impression management based upon the setting and the “script” they are given. For example, if you are a married father of four children, there are certain behaviors expected out of you and a specific script regarding how you are supposed to behave. Impression management is a complex process with a continual give and take of information. People would like to put their “best foot” forward in most situations, creating a situation of dramatic realization. Dramatic realization is where you display the behavior and aspects of your “self” you want others to see (good husband, good father, hard worker). Most people do not want others to see their negative attributes, so we try hard to provide a positive context of who we are to others.

Where crime and deviance stem (according to Goffman) in dramaturgical perspective is through something he referred to as discrediting information. Discrediting information is information people are trying to hide that is not consistent with the managed impressions they are attempting to present to others. Once there is discrediting information, the performance is altered including how others view the person and their behavior based upon roles. For example, a potential piece of discrediting information about a married father of four could be that he is romantically involved with another person besides his spouse. If this is

The picture is from pixabay.com

known (or even assumed), it could change perceptions of him and his performance of his roles.

Irving Goffman also conducted work around total institutions. Total institutions are places where individuals can rarely if ever come and go, also life is very structured and intense (think state hospital, prison). Goffman argued time and reality are different in these total institutions, where time in these institutions will greatly affect the individual’s sense of self and reality. An example would include an individual serving 10 years in prison. As the person is incarcerated, they learn the processes and standards of the prison. The outside world continues to evolve and change, without the individual in prison. Arguably when the person is released from prison in 10 years, they will enter a world and society they don’t really recognize. What they will know is the environment, structure and reality of the total institution. This process is referred to as institutionalization or being institutionalized.

Thoughts from Author Jeff Bry:

“When I was doing juvenile probation, I placed many young people in institutions for correctional rehabilitation and treatment. What was somewhat surprising to me, even after a year in an institution these young people were often changed. They were used to institutional life, getting up at a certain time, certain privileges and restrictions, the rules of the institution. Many seemed initially overwhelmed when released from the institution and needed a bit of time adjust to life in society.”

The picture is from pixabay.com

Association Theory

Differential Association Theory

American sociologist Edwin Sutherland’s (1939) differential association theory asserted that criminality is learned through a process of interactions with others who communicate criminal values and who advocate for the commission of crimes. Sutherland believed that other attempts to explain criminality (genetics, biological, psychological) had flaws and could not fully explain why a person committed a crime. For Sutherland, the role of social learning was at the core of criminality. He summarized his theory through the following nine principles:

1. Criminal behavior is learned.

2. Criminal behavior is learned during interactions with others through communication.

3. Most learning about criminal behavior happens in intimate personal groups and relationships.

4. The process of learning criminal behavior may include learning about techniques to carry out the behavior as well as the motives and rationalizations that would justify criminal activity and the attitudes necessary to commit crime.

5. The direction of motives and drives toward criminal behavior is learned through the interpretation of legal codes in one’s geographical area as favorable or unfavorable.

6. A person becomes delinquent because of an excess of definitions favorable to law violations over definitions unfavorable to law violations.

7. All interactions with others are not equal. They can vary in frequency, intensity, priority, and duration.

8. The process of learning criminal behavior through interactions with others relies on the same mechanisms that are used in learning about any other behavior.

9. While criminal behavior is an expression of general needs and values, it is not explained by those general needs and values because noncriminal behavior is an expression of the same needs and values.

Sutherland combined psychological and sociological principles to create a relational perspective on criminality. Even though it was and is popular to blame mass media (movies, books, social media, television, etc.) for social problems, Sutherland did not believe it was possible to learn criminal behavior through those avenues because they could not provide the required social context for learning.

The picture is from pixabay.com

Thoughts from author Jeff Bry:

“Differential association theory takes the perspective that crime is learned, much like any other type of learning. You learn to walk, talk, ride a bike etc., you also learn about crime and a criminal perspective. Crime is often taught from one person to another in environments like neighborhoods and schools, but certainly also in jail and prison. For certain groups (youth gangs, the Mafia) part of basic membership includes law violating behavior. As these groups are often close knit (almost like family), learning occurs in intimate closely connected groups where the criminal behavior is supported and rewarded.”

Labeling Theory

Labeling Theory

Thank you to Dr. Sean Ashley https://kpu.pressbooks.pub/introcrim/chapter/8-6-labelling-theory/

Labelling theory offers another approach to studying crime and deviance. The roots of this theory can be found in the work of George Herbert Mead (1934/2015), who pioneered a new way of studying social reality known as symbolic interactionism. Mead explains that we construct our social world and our sense of self through the symbols we exchange—language being the most significant form of symbolic communication. Mead did not write about crime, though his student Herbert Blumer (who coined the term “symbolic interactionism”) produced one of the earliest studies concerning the influence of movies on delinquent and criminal behaviour (Blumer & Hauser, 1933).

In a Student’s Own Words:

Question: What is the effect of labeling on crime?

“I believe that labels can both negatively and positively affect people. Most parents aren’t going to label their children as “stupid” because it would more than likely just decrease their self-esteem. But I also think it can leave a positive effect when trying to bring motivation to people. If you get told that you’re “doing a great job,” you’re more than likely going to be inclined to keep up the good work. Labels can also harm in the sense that people may not feel like they are accurately being labeled. This could then lead to controversy and lowered self-esteem. I feel like in a lot of criminal cases, they always claim that the killer was “antisocial” or a “loner.” Usually, these labels caused criminals to act out since they wanted a form of revenge. When using labels, I feel that we just need to be more cautious.”

Mead’s approach to studying social life set the stage for new ways of thinking about crime and deviance. One approach, which came to be known as labelling theory, was formulated by the sociologist Howard Becker. Rather than looking at the qualities or circumstances that make a person turn bad, Becker (1963) asks how this definition of bad behavior was originally constructed. As he explains in his book The Outsiders, “social groups create deviance by making the rules whose infraction constitutes deviance, and by applying those rules to particular people and labeling them as outsiders” (p. 6).

In an earlier formulation of labelling theory, Frank Tannenbaum (1938) refers to the process wherein a stigmatizing label may lead a person to start seeing themselves as a criminal. This occurs through “a process of tagging, defining, identifying, segregating, describing, emphasizing, making conscious and self-conscious” the criminal traits in question (Tannenbaum, 1938, p. 19-20). He calls this process the dramatisation of evil. In this drama, the specialized treatment a young person is given by the police and courts is instrumental in leading them to see themselves as a criminal.

Figure 8.3 Frank Tannenbaum at the Bayonne refinery strike in 1915

Figure 8.3 Frank Tannenbaum at the Bayonne refinery strike in 1915

Grekul and LaBoucane-Benson (2008) explain this dynamic with regard to the formation of gangs comprised of Indigenous youth in the Prairie provinces:

Aboriginals deal with two powerful labels: Aboriginal first, and through stereotyping, gang member. A broader historical context marred by colonialism, discriminatory government practices, and residential schools contributes to a situation where labels stigmatise and propel the labelled further into a life of deviance; the labels can in effect produce further deviant and criminal behaviour. One ex-gang member recalls the police calling his group of friends a gang, so they “began to act that way” and identify as a gang. (p. 71-72)

Labelling theory focuses on how criminality is created and how people come to be defined and understood as criminals through symbolic exchanges. It is a micro-level theory but is nevertheless concerned with the social (rather than individual) dimension of crime and deviance. In this regard, it shares a great deal with Durkheim, who saw crime as an integral part of society. In this view, crime can never be completely eliminated from society as it plays a role in defining the boundaries of a social group. Critics charge that this approach can lead to a morally relativistic view of crime where there is no essential reason why one act should be considered criminal and another not. Durkheim reminds us, however, that even if laws differ from society to society, human beings require social regulation if they are to remain at peace in the world.

Media Attributions

Frank Tannenbaum © Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division is licensed under a Public Domain license

In terms of discussions of deviance and labeling, American sociologist Howard Becker (1963) believed that “deviance is not a quality of the act the person commits, but rather a consequence of the application by others of rules and sanctions to an offender.” In other words, according to Becker’s labeling theory, someone only becomes deviant once that label is applied to them. This can occur through negative societal reactions that ultimately result in a tarnished and damaged self-image and negative social expectations.

Think about the labels that exist in our society: one of the most difficult ones to see past for many is the label of the “criminal.” For example, what do you think immediately when someone tells you they were in jail or prison? Right away, a label is created and it usually isn’t created from direct knowledge but a range of stereotypes that have been obtained over the years. Once the label is created it affects how the individual is treated and viewed.

When someone asks you about yourself, what is the first thing you tell them? Do you say you are a student, or a brother/sister, or a parent? Our master status, or most prominent identity description, according to Becker, defines our social position and a criminal label can become a master status overriding all others (Becker, 1963). Having a criminal record can make it difficult for an individual to get employment, buy or rent a home/apartment, or even find a healthy relationship mainly because of the negative label. In fact, there has been a movement to remove the question that asks about past criminal convictions from job applications because, for many, that automatically disqualifies the individual from job consideration.

Should we forever be known and labeled for our worst day? Everyone has participated in activities that could put their master status in jeopardy but for many, that information is never discovered. However, in a society now that records so much of its behavior, our past indiscretions could change our future lives even if we have changed as individuals. Once a negative label is assigned, then it is a difficult process to regain a positive master status.

This damaged self-image could result in a self-fulfilling prophecy, which is a process in which an originally false expectation leads to its own confirmation. In other words, if you treat someone like a criminal then they may ultimately become a criminal to confirm the false expectations of society.

Impact of Diversion Programs on Juveniles

Juvenile diversion programs hold youth accountable for their behaviors without resorting to legal sanctions (meaning they will not end up with a criminal record). This concept can be seen as arising from two theories: labeling and differential association. Labeling theory views the experience of processing certain youth through the juvenile justice system as potentially doing more harm than good since it can stigmatize them for committing relatively minor acts that could have been handled outside of the formal system (Lundman, 1993). Labeling a juvenile a “delinquent” can affect the way in which the juvenile defines themselves and how society perceives them which, in turn, can influence future behaviors.

Differential association theory states that juveniles who become part of the system will end up adopting antisocial attitudes and behaviors from their delinquent peers. The more youth are exposed to more advanced delinquent youths and adults, the more it is thought to have a criminogenic effect on the individual. This increases the chance of the confined youth reoffending. In other words, they learn more bad behaviors from others while they are locked up with them. According to the theory, the more you limit a juvenile’s exposure to the juvenile justice system, the less likely they will adopt the attitudes and behaviors of those present in the system.

Diversion programs intend to minimize the effects of labeling youth as deviant while limiting their opportunities to associate with delinquent peers and adopt antisocial behaviors. Adolescence is a time of discovery and mistakes can be made but without diversion programs some juveniles’ adolescent mistakes could limit their opportunities for the rest of their lives.

Shaming

John Braithwaite and colleagues (1989) discuss the power of shaming as a means of controlling behavior. Braithwaite argues shaming is potentially an effective method of reducing crime, especially if it is conducted in an appropriate manner. Stigmatic shaming is more punitive shaming, where the individual is ostracized from society and most of its members. Braithwaite argues reintegrative shaming to be the more appropriate method of shaming. Reintegrative shaming takes the approach of “condemning the crime, not the criminal.” The person still has value and can make contributions to society, so it is the job of society to assist the offender in reintegrating into their community. This approach borrows heavily from many Asian cultures, where reintegrative shaming is commonly used.

The shaming approach takes aspects of labeling theory, using perspectives of stigma and negative labels that may further affect criminal behavior. The United States tends to lean towards stigmatic shaming, where the offender is labeled and treated fairly poorly once released from prison. Reintegrative shaming offers the potential for a community and opportunity for the offender.

Image from Pixabay.com

In a Student’s Own Words:

Question: What is the effect of labeling and shaming on behavior?

“I just wanted to briefly note something I thought was interesting about both Reintegrative Shaming, and the Dramaturgical Perspective. In modern psychology, shame is seen as something more sort of general, and that is attached to the individual, while guilt is more specific and has to do with specific actions, and, some believe, that guilt is a kind of tool for maintaining human relationships, as guilt gives us the opportunity to fix whatever it was that violated the rules or expectations of certain relationships. (In this way, I think it could be thought that Goffman’s discrediting information is what can be dealt with through the function of guilt and relationship management, however I’m not quite sure about how much that information is essentially attached to the individual). In terms of this psychological definition of shame versus guilt, I think Braithwaite hits the nail right on the head with his differentiating what sticks with the individual (shame and stigma) and what is the specific thing which must be rectified or dealt with in some way (guilt), it’s just that, at least in our book’s telling, Braitwaite didn’t explicitly separate guilt and shame the way psychologists might. But expanding on Braitwaite’s points about stigma, is, I believe, correct there, in that stigma and shame go hand in hand, and this is why in psychology and social work it is explicitly discussed to attempt to use person-first language, and to not conflate the individual with the stigmatizing label, to, for example, call a man suffering with schizophrenia a man suffering with schizophrenia, rather than a schizophrenic. This can is also talked about in how you might admonish your kids for example, and the importance of, rather than saying something like “you’re a messy person,” saying, “you made a mess,” that way you are separating your child out from the label, and in pointing out the specific action (making a mess) there is something about which the child can feel guilty and make things right, but, when the child becomes used to hearing “you’re a messy little such and such,” you’re dealing with shame, rather than guilt, and shame is something that can’t be so easily dealt with and can cause the child to decide that if they are a messy person, what good is it to try to do better.”

Social Learning Theory

Social learning theory asserts that people learn attitudes and behaviors conducive to crime in both social and nonsocial situations from positive reinforcement (rewards) and negative reinforcement (punishments). An absence of rewards could make criminal behavior more attractive while the presence of punishment may steer an individual away from similar behavior.

Sociologist Robert Burgess and criminologist Ronald Akers (1966) believed that “criminal behavior is a function of norms which are discriminative for criminal behavior, the learning of which takes place when such behavior is more highly reinforced than noncriminal behavior.” In other words, if deviant behavior is rewarded then the individual will continue with that behavior similar to a student who is rewarded for good grades and strives to continue to achieve good grades.

Social learning occurs in two ways: imitation and reinforcement. An individual observes what happens to others and if the actions are rewarded then it is more likely the actions will be copied. For instance, if a friend of yours illegally obtains a pair of limited-edition shoes and is praised by others, then it is more likely that you would try to obtain the shoes in a similar manner with hopes of receiving the same praise.

This theory is similar to differential association theory that focuses on imitating behavior that has been modeled by those around you, but it broadens the focus by specifying the process of learning from other people by including the observation of whether that person is being rewarded for their behavior. This becomes part of the decision to become deviant.

Dr. Zachary Rowan and Michaela McGuire, M.A. made the following contribution to this chapter specific to social learning theory. https://kpu.pressbooks.pub/introcrim/chapter/9-4-social-learning-theory/

While Sutherland (1947) developed one of the most well-known theories, one limitation was his description of precisely how learning occurred. In Proposition #8 of differential association theory, Sutherland (1947) states that all the mechanisms of learning play a role in the learning of criminal behavior. This suggests that the acquisition of criminal behavior involves more than the simple imitation of observable criminal behavior, but Sutherland does not fully explain how exactly definitions from associates facilitate criminal behavior. Building off the recommendations of C.R. Jeffery (1965) to integrate concepts of operant behaviour theory into differential association theory, Robert Burgess and Ronald Akers (1966) reformulated the propositions developed by Sutherland into what was initially called differential-reinforcement theory. Akers (1998) eventually modified differential reinforcement theory into its final form, social learning theory (SLT).

SLT is composed of four main components: 1) differential associations, 2) definitions, 3) differential reinforcement, and 4) imitation. The first two components are nearly identical to those observed in differential association theory. Differential association was expanded to be inclusive of both direct interactions with others who engage in criminal acts, and more indirect associations that expose individuals to various norms or values. For example, friends of friends who may not directly interact with an individual still exert indirect influence through reinforcing behaviors and definitions of a directly tied friend. Definitions were similarly described as attitudes, or the meanings attributed to behaviors and can be both general and specific. General definitions reflect broad moral, religious, or other conventional values related to the favorability of committing a crime, whereas specific definitions contextualize or provide additional details surrounding one’s view of acts of crime. For example, a general definition of crime may reflect an individual’s belief that they should never hurt someone else, but the use of substances is acceptable because it does not harm anyone else. Recent efforts have also underscored that attitudes towards crime can be even more specific and depend on situational characteristics of the act (e.g., Thomas, 2018, 2019). For instance, an individual may hold the general definition that they should never fight someone; however, they may adopt a specific definition that suggests that if someone insulted your family or started the conflict first, then perhaps fighting is acceptable.

Borrowing from principles of operant conditioning, Burgess and Akers (1966) argued that differential reinforcements are the driver of whether individuals engage in crime. This concept refers to the idea that an individual’s past, present, and anticipated future rewards and punishments for actions explain crime. If an individual experiences or anticipates that certain behaviors will result in positive benefits or occur without consequences, this will increase the likelihood that the behavior will occur. This process is comprised of four types of reinforcements or punishments:

Positive reinforcement: reinforcements that reward behaviour, such as money, status from friends, and good feelings, that will increase the likelihood that an action is taken.

Positive punishment: the presentation of a negative or aversive consequence, such as getting arrested, injured, or caught, after a behaviour is exhibited to decrease the likelihood it will happen again.

Negative reinforcement: reinforcements that help a person avoid the negative consequences of a behaviour, such as avoiding getting caught, arrested, or facing disappointment from others, that will increase the likelihood that an action is taken.

Negative punishment: the removal of a positive reinforcement or stimulus after an undesired behaviour occurs to decrease the likelihood a person will engage in the behaviour again. For instance, if a child gets into a fight with a friend their parent may take away their cell phone, cut off their Netflix access, or remove other privileges.

Lastly, imitation is the mimicking of a behavior after observing others participate in the behavior. Within intimate personal groups, individuals will observe criminal acts or substance use that are often are used to facilitate the initiation of the behavior. Once the behavior has been engaged in, imitation plays less of a role in the maintenance of or desistance from that behavior.

Example: Ed Kemper and Social Learning Theory

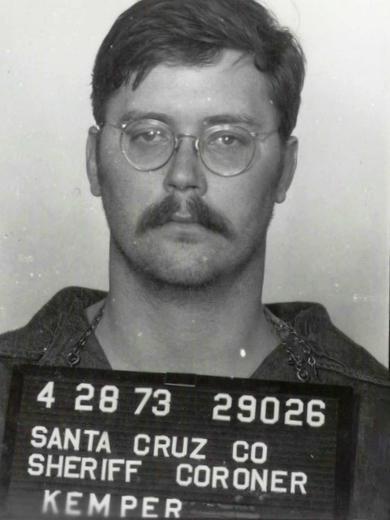

Figure 4.7: Ed Kemper’s Mugshot (1973).

It would be uncommon for serial killers to learn how to kill by watching others, however, if the focus is turned to the idea of rewards and punishments, then social learning theory could be applied to those individuals. Serial killers in interviews have confessed to being humiliated by parents, caretakers, and the opposite sex. When faced with the same issues later in their lives, the anger and resentment that has built up over the years may have transformed the individual into a murderer.

The serial killer Ed Kemper (figure 4.7) is an example of a serial killer who developed anger toward his caregivers and then later went on to kill them. Ed Kemper was featured in the Netflix show Mindhunter and with the exception of his grandfather (he killed his grandparents at age 15), all of his victims were women. Kemper not only killed his victims but degraded them after death which allowed him to enact behaviors that he wanted to previously direct toward his mother. Later, he killed his mother.

Kemper spoke of his hatred for his mother because of the psychological abuse she subjected him to as a child and he chose to murder her in order to make the killings stop. When he came to the conclusion that ultimately it was his mother he wanted to kill all along, Kemper surrendered himself to authorities. Kemper learned to kill indirectly through the hate he endured from his mother and sisters. His family did not treat him as a human being and later he accepted that label and became a serial killer.

Licenses and Attributions for Interactionist Theories

“Interactionist Theories” by Curt Sobolewski is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Social Learning Theory” by Dr. Zachary Rowan and Michaela McGuire, M.A. is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 4.7 Photo of Ed Kemper’s Mugshot (1973) is in the Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

References

Introduction to Criminology Copyright © 2023 by Dr. Sean Ashley is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Introduction to Criminology Copyright © 2023 by Dr. Zachary Rowan and Michaela McGuire, M.A. is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Braithwaite, J. (1989). Crime, Shame and Reintegration. Cambridge University Press.

Goffman, E. (1959). The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Doubleday.

Goffman, E. (1961). Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates. Anchor Books.

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Prentice-Hall.