6 Ch. 6 Social Structure Theories

Curt Sobolewski and Jeff Bry

Ch. 6

Social Structure Theories of Crime and Crimes of Opportunity

A special thank you to the Introduction to Criminology OpenOregon resource for much of this chapter. https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/criminologyintro/

Introduction

Sociology has been a dominant force in the discipline of criminology for decades, at both a macro and a micro level of analysis. Two competing forces in the sociological explanation of crime include the anomie perspective and the imitation perspective. Each perspective provides a different sociological analysis regarding crime and criminal behavior. We will begin the discussion with anomie theories, which are more closely correlated to social structure theories. Ch. 7 will examine theories more strongly related to the imitation perspective, which more closely aligns with social process theories. Viewpoints of anomie and imitation are explained in this chapter, with a discussion of the social structure theories of sociology. The perspectives of anomie and imitation are sometimes referred to as “early theories” in sociology.

Anomie

Emile Durkheim, a French sociologist who officially established the field of sociology in the 1890s, believed that we have to look at what makes up a society to understand its social issues. Durkheim claimed that as society develops and grows, unstable relationships evolve between individuals and the community. The larger and more sophisticated society becomes, the greater difficulties the society has in socializing its members or teaching them how to fit into the society as a whole.

Durkheim saw that there could be some causes of crime within a society, and it all came down to the cohesiveness of the group. He believed that individualism (focusing on oneself instead of the group wellbeing) could be a cause of deviance, or going against the norms of that society.

In today’s society, Durkheim would look at the gap between the rich and the poor and identify that as deviant individualism in the form of greed, or a deviant adaptation to the pursuit of “success.” When such deviances happen and the social equilibrium is disturbed (someone rocks the boat), people are set adrift not having comfort or an understandable place in society. The only way to fix this problem and restore balance or equilibrium is to create a new or updated social equilibrium by working these deviant adaptations into the “new normal” of the society. Basically, the social norm is updated by accounting for individualism within the group.

Think about the last time you heard a news story about someone or a group singled out as being “problematic” in society. Were their issues completely of their own doing? Or were their issues part of a change in society’s structure that caused an imbalance which needed to be addressed through policy?

For example, in the 1980s and 1990s, manufacturing jobs started to leave the United States. This disturbed the equilibrium by removing a solid wage-earning unskilled profession and replacing it with absolutely nothing. Individuals who did not have the education or training for other types of employment were left to their own devices and needed to discover how to earn a wage in a society where their skill was no longer needed. What do you think was the overall result of this disruption in the equilibrium? How would you react if your job was taken away and what you could do no longer mattered in this country?

Social disturbances like this are problematic because (besides hurting people who lose their job, sense of purpose, and ability to take care of their family) it creates a social condition where things are unstable, unfair, and confusing. Durkheim called this social condition anomie, which is the relative absence or confusion of norms and rules in society. He explained that disturbing the norm in this manner was at the core of explaining deviance. In other words, when there is a breakdown in the social norms, society devolves into anomie. What follows is a person feeling adrift with little connection to society, making them no longer care about the group and lifting any constraints they may have had on their behavior as a result. We see this in times of economic decline; inevitably, crime rates increase. The opposite is true when the society is financially prosperous; crime rates decrease.

Anomie provides valuable insight into the changes of crime rates within society. It also can direct ways in which policy can have a direct effect on crime in society. When significant social, economic, or political changes occur, this change can have a direct impact on the crime rate—whether good or bad. Durkheim influenced a number of theorists such as Robert Merton (discussed later in this chapter) who would later study crime and take this theory of anomie deeper into the explanation of crime in society.

Theory of Imitation

Gabriel Tarde was another French sociologist and criminologist working at the same time as Durkheim. These two frequently and publicly disagreed. Tarde focused predominantly on criminology over sociology and tried to figure out how people became criminally involved. In his book, Le Lois de l’imtation (The Laws of Imitation) published in 1890, he made an argument that people do what they know. Tarde was the first theorist to associate crime with learning in what he called the laws of imitation.

According to Tarde’s theory of imitation, he believed that crime is the result of imitation or modeling the behaviors of others. When a person learns new responses by observing others, this is called modeling. He did not view people who committed crimes as biologically or psychologically different from noncriminals; instead, he saw criminals as just modeling the deviant behaviors they saw around them. He felt this was especially true for fathers and their sons (like father, like son). His theory went against the commonly held belief that criminals were simply bad people. If crime, as Tarde argued, is learned by observing and imitating the criminal behavior of those around the individual, then crime could also be unlearned. Tarde believed that this happened more likely in dense, urban areas where individuals had exposure to more people as models, ripe for imitation.

According to Tarde, imitation is the source of all progress that occurs, both good and bad. By recognizing the power of imitation, people could try to control the outcome. He believed that more positive connections and better communication could lead to greater production of good outcomes. An important factor in his “laws of imitation” is that individuals need to be in close contact. People are influenced by those with whom they have a relationship or at least those whom they witness regularly. Think about who you were in close contact with growing up. Your parents? Other family members? Neighbors? The answer to this question could determine the course of your life. According to Tarde, a neighbor who was a medical doctor and a neighbor who was a petty thief both could have a great influence on the behaviors of a child who is observing. For this reason, Tarde named close contact as the first of three “laws” of his “laws of imitation.”

The second law is related to the imitation of superiors by inferiors. Tarde said people are influenced by those who have power or are in positions of power. The person in the inferior position (e.g., child, employee, new kid in school) may want to see themselves as “superior” and by doing so may imitate the behaviors and attitudes they see in those who hold the power (e.g., parents, boss, cool kid in school). Another example is when politicians make certain claims, people who are in their same political party are likely to believe them and not question what they say because it comes from someone who has power.

What is the cost to the “inferior” person, though, of conforming to what the “superiors” are saying and doing? Think about the attack on the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021. Quite a few individuals who had no power imitated those in power who they admired and that led them to criminal acts. Their lack of power also meant they were not able to fight a criminal justice system that did not favor their social status, so many of them have had to face criminal sanctions while those they were imitating remain free.

The third and final “law of imitation,” according to Tarde, is insertion. This means that the new behaviors that were learned from imitating someone you look up to replace your old behaviors. Tarde believed people would observe someone else, want to be more like them, copy their behaviors, then adapt them to make them their own. This could mean “copycat” crimes like we see when some horrible event gets a lot of media attention. It could also mean using new technology to update the crime or even changing weapons from a knife to a gun. The behavior is customized and personalized as it replaces the person’s old behaviors.

Tarde also recognized that opposition can occur. This can happen when someone is torn between different sources for modeling or when new and old ideas collide. Opposition leads to some sort of adaptation. In other words, the person doing the imitating might combine what they observe and learn from more than one influence. In this manner, they create their own way of behaving and thinking, which was fed by more than one source.

So far, we have looked at Durkheim who believed that society was a collective unity, and at Tarde who saw society as individualistic. Now, we will look at theorists who explored the effect of different societal structures on crime.

Licenses and Attributions for Early Theories

“Early Theories” by Curt Sobolewski is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Social Structure Theories

Structural functionalism in sociology explores the ways in which different parts of the community interact with each other. A structural functionalist sees that the existence of a social structure provides a continuous benefit to society. For instance, if the educational system is strong, society thrives. If the educational system is weak, society suffers. The weakened system results in social issues, such as crime and poverty. Durkheim is considered a structural functionalist who has influenced theorists to look at the strength of the social structure to determine the health of society.

Conflict Theory

Figure 4.2 Max Weber, 1918.

German Sociologist Max Weber (figure 4.2) studied the conflicts between social groups in the early 1900s. Social groups are created by economic forces (similar social class, income level, types of employment); by social forces (similar values and beliefs); and by political forces (levels of social status and power, honor or prestige, respect). These differences can lead to the creation of interest groups that join forces to exercise power or influence.

Weber believed conflict among these social groups was inevitable, which is the basis for what he called conflict theory. He argued the authority figures in society are religion, business, government, and the law. These are not going to have the same interests, priorities, or goals as all social groups thereby creating conflict between those who benefit from the rules. Furthermore, those who do not benefit from the rules are likely to be exploited, discriminated against, and marginalized. For this reason, there will be conflict between social groups and that leads to criminal or deviant behavior.

Twists on Conflict Theory

Weber’s conflict theory was an expanse of Karl Marx’s (1848) philosophy about economic conflict. Marx saw conflict originating in his version of the “haves and have-nots.” He blamed capitalist society for creating great wealth for a select few and extreme poverty for many others. He saw the capitalists as owning the means of production (businesses) and the proletariat (workers) as the group that is exploited through their labor. Marx saw this natural conflict that he believed would create class wars and revolution as the workers replaced the capitalists. As we know, there are still “haves and have-nots” and a giant gap between the wealthy and the rest of us, so the workers have still not replaced the capitalists. However, that does not mean there has not been conflict.

Around the same time as Weber, Dutch criminologist Wilem Bonger was also building upon Marx’s claims. Bonger connected capitalism as argued by Marx to the promotion of greed and self-interest that he referred to as excessive egoism. He, like Marx, viewed capitalism as the core problem. Bonger argued the poor commit crimes out of need or a sense of injustice when they are pushed by the inequalities that exist within a capitalistic system. He did not claim that poverty by itself caused crime. Rather, when poverty was merged with negative social forces such as racism, individualism, and materialism, these conditions would be very conducive to the rise of criminality.

Another twist on conflict theory came from Swedish-American sociologist Thorsten Sellin. He studied the role of culture conflict in causing crime (1938). Sellin saw behavioral norms as expressions of group cultural values. In a homogenous society, where everyone’s the same, there is a consensus on what is right and what is wrong. But in a heterogeneous society with cultural differences, conflict may exist regarding what is right and wrong. Sellin said when the values and beliefs of two different groups collide, culture conflict results.

Strain Theory

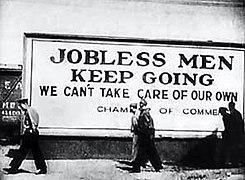

Figure 4.3 Unemployed men during the Great Depression.

It has been said that sociologist Robert Merton “Americanized” Durkheim’s anomie theory. Merton (1957) argued that U.S. society considers economic success as an absolute value, hence the “American Dream.” As a result, the pressure to achieve economic success overrides any need to fit in with the rest of society’s rules and follow their laws.

In a Student’s Own Words:

Question: What is the effect of disorganization, strain and poverty on crime?

“I don’t think people being from poverty and drugs and alcohol causing crime are mutually exclusive. Addiction is more prevalent in more economically depressed areas. https://www.addictioncenter.com/addiction/low-inco…I wonder though, since crime is already higher in economically depressed areas, whether particular types of substance addictions combined with indigence raises the chances that someone gets involved in criminality. (I’m using criminality in a sociological sense, not the legal sense, as being addicted to substances already causes law-breaking, whether or not it is reasonable or healthy to punish people for their addictions—so in this context I don’t take the legal perspective seriously.)”

In American society, there is a widely acknowledged goal of some level of wealth that tends to be represented by home ownership, two cars in the driveway, a picket fence, and a dog (probably a golden retriever). However, being able to get this “American Dream” is actually not possible for a lot of people. The general message is to work hard, follow socially accepted steps toward your goal, and you will be rewarded. This does not work out in reality for many Americans and the distance between what someone wants to achieve and what they are actually able to achieve because of various obstacles and limitations is strain (figure 4.3).

Merton’s strain theory is that when someone faces strain, they experience anomie which Durkheim explained as the relative absence or confusion of norms and rules in society. When applied to strain theory, anomie is the willingness to take alternative routes or use alternative means to get to the goals you want. In other words, if a big television is a symbol of success and happiness, someone may be willing to steal one if they cannot afford to buy one so people think they are doing well.

Merton witnessed this phenomenon firsthand during the Great Depression. He saw that people still valued American culture and its focus on economic success but access to legitimate opportunities to reach that success was extremely limited. When confronted with the contradiction between culturally accepted economic goals and socially accepted (and limited) means of achieving success, many Americans experienced anomie and that contradiction produced strain.

How does someone respond to this strain? The majority, according to Merton, accept their reality and conform by accepting that they need to accept lower goals that can be achieved through legitimate means. They achieve their own level of success within the rules of society even if they never reach their aspired goals. However, not everyone is willing to adjust their goals, especially when being bombarded with constant messaging that they need more through social media, music, advertisements, television shows, movies, etc.

Social Disorganization Theory

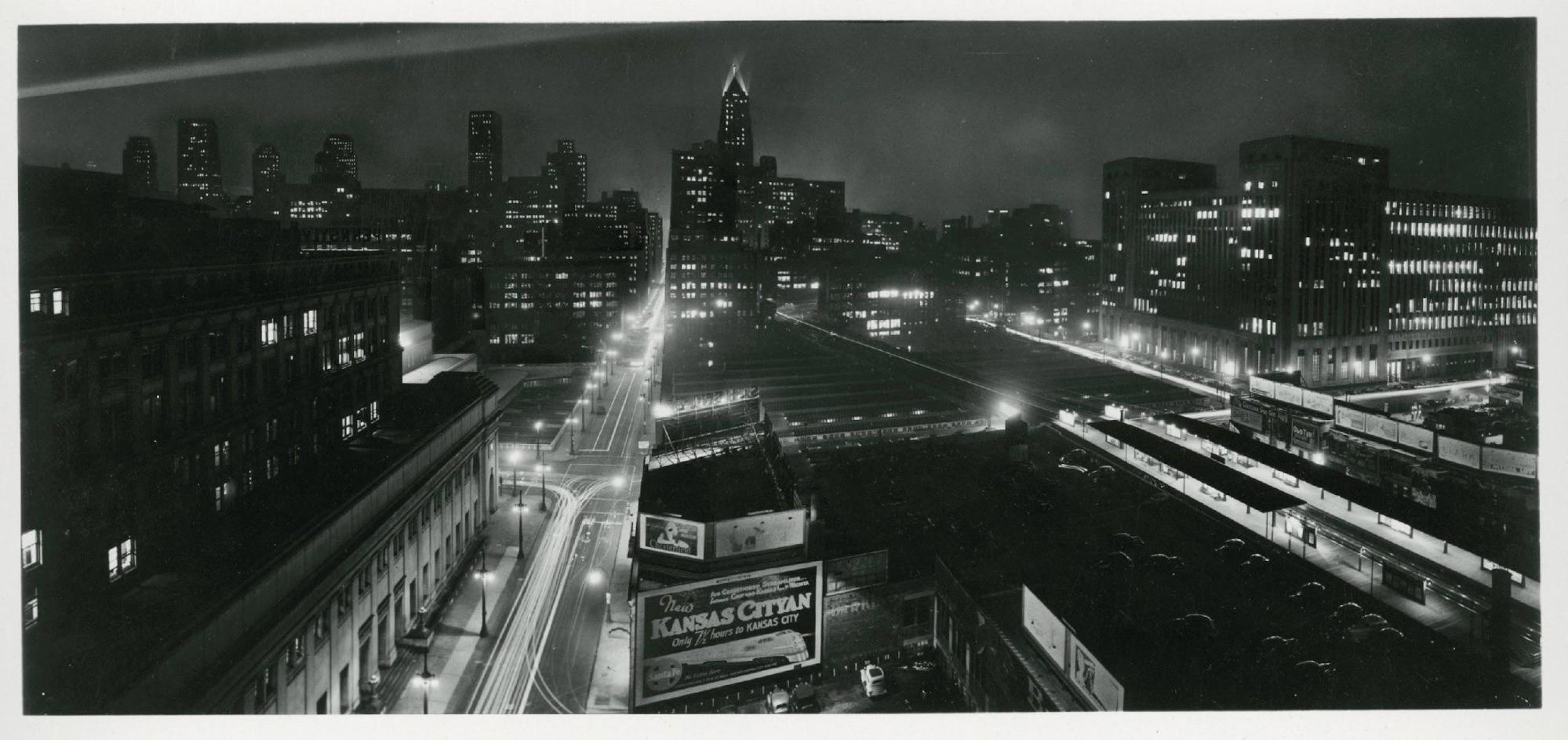

Figure 4.4 Chicago 1930s.

For the sociologists at the University of Chicago, the diverse city was a perfect setting to test their theories, leading to several new approaches to understanding crime in urban settings. One popular theory that came out of the Chicago School is the social disorganization theory.

Sociologists Clifford Shaw and Henry McKay (1942) applied some knowledge gained by other scholars at the school to their own examination of tracking crime in certain Chicago neighborhoods. They looked at Chicago’s geographic distribution of crime and delinquency and found that areas of high crime were also characterized by weak community controls. Social disorganization theory claims that neighborhoods with weak community controls caused by poverty, residential mobility, and ethnic heterogeneity will experience a higher level of criminal and delinquent behavior.

The neighborhoods they studied that had consistently high crime rates consisted of mostly low-priced or subsidized rental properties, a large portion of the residents being on public assistance, and high rates of unemployment. This setting of poverty meant that those who stayed living in that area long-term were those who had no choice, versus those who moved out as soon as they gained some financial stability. Leaving at the first chance they got was the cause of high residential mobility.

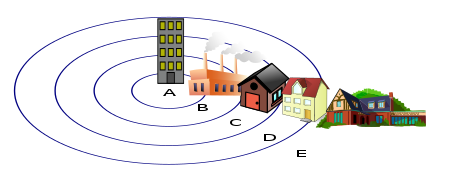

Picture source Wikimediacommons.com

From the image above, the concentric zone model suggests crime is concentrated in the “inner” zones, as these neighborhoods are less expensive, more run-down and people do not want to stay there long-term. These inner zones are more industrial, congested and are more disorganized. The outer zones (residential, commuter) are generally more expensive to live in and are more organized. As the level of organization increases, crime decreases.

There was also a steady stream of new people moving into the neighborhood as they moved to the city or were no longer able to stay in their previous neighborhoods. As a result, there was constant movement in and out of the area with no one considering it home or making any investment in the area. Such an investment would otherwise create a sense of community. However, these neighborhoods were marked by high ethnic heterogeneity coupled with high residential mobility, so for the time people lived in the area, they socialized with and helped only people within their limited comfort zone of shared ethnicity. There was no community building or getting to know others in the neighborhood, which is usually the source of informal social controls(keeping an eye on each other’s kids). The frustration of growing up in such a neighborhood could also fall within the general strain theory.

Picture source pixabay.com

Image from pixabay.com

In a Student’s Own Words:

Question: What is the effect of disorganization, strain and poverty on crime?

“When it comes to victimization I think it is just easier to do it to someone who is poor because they may lack knowledge of what they can do to get justice for said crime and they more then likely have less money so they cannot pursue a lot of options for payback for the crime such as time consuming court cases or even just being able to take the time to talk to police. I also feel people who are experiencing poverty feel like the police won’t take them seriously because they don’t have money. “

Sampson’s Micro-Social Disorganization Theory

Robert J. Sampson’s 1986 study on micro-social disorganization explored how local community structures and informal social controls influence crime rates. His research focused on how neighborhood-level social organization, particularly family structure and residential mobility, affects delinquency and criminal behavior. Sampson’s research concentrated on small-towns and other cohesive neighborhood based communities, where crime control and community support are expected. In these more “organized” towns and neighborhoods, neighbors are more likely to know each other and to pay attention to small (and large) differences in their environment and neighborhood. Sampson argued these neighborhoods and communities have higher levels of collective efficacy, essentially meaning cohesion, support and communal obligations and protections. Some of the findings of Sampson include:

-

Family Disruption and Crime:

- Sampson argued that family disruption (e.g., single-parent households, divorce rates) weakens informal social controls, leading to higher crime rates.

- Communities with high rates of single-parent families tend to have weaker supervision of youth, increasing delinquency.

-

Residential Mobility and Crime:

- High levels of residential mobility (frequent moving in and out of a neighborhood) disrupt social cohesion and reduce collective efficacy.

- Communities with frequent turnover struggle to maintain strong social ties, leading to a breakdown in informal social control.

-

Micro-Social Disorganization:

- He proposed that micro-social disorganization, seen in weak family structures and transient populations, contributes to higher rates of youth crime and delinquency.

- Unlike macro-level disorganization theories, which focus on broad societal structures, his research highlighted localized, small-scale disruptions in social networks

Sampson, R. J. (1986). Crime in cities: The effects of formal and informal social control. Crime and Justice, 8, 271-311.

From Author Jeff Bry:

“Growing up in a small town, I knew if I misbehaved at school, at the park, or even on the street and someone saw me, there was an excellent chance they would call my parents. The teachers knew my parents, as did most people in our small town. I was also aware that if I misbehaved, a neighbor may feel free to yell at me or tell me to “straighten up” if they witnessed why I was doing.

Small towns are also interesting because generally people know each other, they are also invested in order and cohesion in their town. My mother still lives in my home town, she knows all of her neighbors by name, where they work, also when and where they go on vacation (and for how long) etc. This level of cohesion reduces crime, as people watch out for each other, alert each other of issues and work together to reduce problems and potentially crime. Less organized communities and neighborhoods have much less of this, people may mind their own business and may not even know their neighbors.”

Merton’s Strain Theory

Merton’s Strain Theory is a sociological framework that explains deviance as a result of the tension or “strain” between culturally prescribed goals and the means available to achieve them. Developed by sociologist Robert K. Merton in the 1930s, Strain Theory is grounded in the idea that society sets common cultural goals (such as wealth, success, or status) but does not provide equal access to the legitimate means (education, employment) to achieve these goals. This imbalance leads to strain, particularly among disadvantaged groups, and motivates individuals to resort to deviant or criminal behavior to attain societal expectations.

Merton identified five modes of adaptation to strain:

Conformity: Most people in society conform to the goals and means despite the strain they experience. They continue to work within the system, using socially acceptable means (e.g., education and employment) to pursue goals such as financial success.

Innovation: Individuals accept the societal goals but reject the legitimate means to achieve them. Instead, they innovate by turning to deviant means, such as crime, fraud, or other illicit activities. This is common in situations where individuals lack access to legitimate opportunities.

Ritualism: These individuals abandon the societal goals but rigidly adhere to the means. For instance, a person might continue to follow rules and routines of work, not necessarily to achieve success, but simply to maintain stability, even though they no longer aspire to wealth or status.

Retreatism: In this adaptation, individuals reject both the societal goals and the means to achieve them. They withdraw from societal expectations, often retreating into substance abuse, vagrancy, or isolation. They essentially “drop out” of the societal competition for success.

Rebellion: Rebels not only reject the societal goals and means, but they also seek to replace them with new ones. They may engage in social movements or radical behaviors, attempting to create a new societal order that aligns with their values. This adaptation is common among activists or revolutionaries who wish to change the status quo.

Merton’s Strain Theory provides an explanation for why certain individuals, particularly those in lower socioeconomic statuses, may resort to crime or deviant behavior. It emphasizes the role of structural inequalities in producing deviant behavior, noting that when legitimate avenues for success are blocked, people may turn to alternative, sometimes illegal, paths to achieve success.

Merton’s ideas were further developed by other scholars, like Albert Cohen who focused on the role of status frustration in the formation of delinquent subcultures, and Cloward and Ohlin, who introduced the concept of differential opportunity structures, suggesting that access to both legitimate and illegitimate means varies across social environments. These contributions expanded the understanding of how strain can lead to different forms of deviance based on one’s access to resources and opportunities.

References:

Merton, R. K. (1938). “Social Structure and Anomie.” American Sociological Review, 3(5), 672–682.

Cohen, A. K. (1955). Delinquent Boys: The Culture of the Gang. New York: Free Press.

Cloward, R. A., & Ohlin, L. E. (1960). Delinquency and Opportunity: A Theory of Delinquent Gangs. New York: Free Press.

General Strain Theory

American criminologist Robert Agnew expanded Merton’s strain theory to include short-term frustrations as possible causes of strain in an adolescent’s life. In general strain theory, Agnew argued that social injustice or inequality may be at the root of strain instead of just the search for the American Dream (1992). Agnew would point to that negative interaction as a possibility of strain in an individual’s life, particularly with adolescents. The feeling that the deck is stacked against them and there is no reason to even attempt to live by society’s rules can lead an individual to criminal or delinquent behavior. Delinquency, according to Agnew, becomes a natural reaction to the stresses of adolescence.

Merton’s theory of strain depicted individuals working toward an unattainable goal, but Agnew’s theory suggests that some individuals are running away from something instead. This may include punishment by their parents or negative relationships that exist at school. According to Agnew (1992), adolescents are “pressured into delinquency by the negative affective states – most notably anger and related emotions – that often result from negative relationships.”

In a Student’s Own Words:

Question: What is the effect of disorganization, strain and poverty on crime?

“Poverty can lead to crime through various pathways. For instance, limited access to resources and opportunities may push some individuals toward criminal activities as a means of survival or economic gain. Moreover, areas with concentrated poverty often experience various social problems, including crime, due to factors of inadequate housing, schooling, and employment opportunities. On the flip side, people living in poverty may also be more vulnerable to becoming victims of crime. They might live in neighborhoods with higher crime rates or lack the means to secure their property and personal safety.”

Agnew identified three distinct types of strain for adolescents:

1. The failure to achieve positively valued goals;

2. The removal or loss of something valued by the individual (suspension from school, relationship breakup, death of a family member, divorce); and

3. The presence of negative stimuli (child abuse, victimization, negative school experiences).

All juveniles will experience at least one of these types of strain during their lives, so then why do some participate in delinquent behavior while others do not? Agnew (1992) proposes four factors that predisposed juveniles to delinquency.

They reach the limit of their known coping strategies, so their reaction is anger and frustration.

They experience chronic strain which lowers the threshold for tolerance of adversity, meaning that juveniles are unable to deal with increasing levels of strain, acting out even when small events happen in their lives.

The chronic strain is cumulative, building their anger into hostility and avoidance.

As things get more difficult for them, they become prone to fits of anger that focus on those they perceive are the cause of their injustices.

Delinquency is then the natural consequence of the strain in their lives.

Picture source pixabay.com

Status Frustration Theory

In his book The Culture of the Gang, Albert Cohen (1955) proposed status frustration theory, which argues that four factors—social class, school performance, status frustration, and reaction formation (coping methods)—contribute to the development of delinquency in juveniles. His theory assumes that crime is a consequence of the creation of youth subcultures in which deviant values and moral concepts dominate.

Cohen contended that middle-class goals serve as a measuring rod for societal success. When we think about achievement for adolescents, how is it measured? Through SAT scores? Extra-curricular activities? GPA? Does the measure of achievement look at the resources each child has been given? For instance, what if a student’s SAT score looked differently if they came from a failing school compared with scores from students who attended a well-resourced school? Are SAT scores viewed differently if a child was able to pay to take a prep class compared to one who wasn’t able to afford one? In Cohen’s view, this is just part of the creation of the middle-class measuring rod where students are set up to fail because they do not have access to the resources other students have. Students without support may not see value in education and end up not pursuing a higher degree because they believe they have already been set up to fail.

Like anomie, strain, and general strain theories, the frustration that is created by not obtaining desired goals can lead to deviance. However, it is important to note, in all of these cases of strain and frustration, the majority of juveniles are not deviant and do conform to the proposed standards of society. However, those who move toward delinquency may be doing so because there is a sort of status they believe can be achieved through delinquency. Whether it be through violence, monetary delinquency, or just drug/alcohol use, these juveniles finally achieve a level of status they couldn’t outside of their delinquent behavior.

An interesting part of the school system is how, if a child misbehaves, the punishment is suspending or expelling them from school. If their grades don’t meet the minimum, then they may be removed from a sports team or other extracurricular activity that could have given them the status they desired and the taking away of their activity could lead to frustration and possible deviant behavior. Cohen’s main points will be continued in the section in this chapter on “Subculture Theories.”

Licenses and Attributions for Social Structure Theories

“Social Structure Theories” by Curt Sobolewski is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 4.2 Photo of Max Weber, 1918 is in the Public domain.

Figure 4.3 Photo of Unemployed men during the Great Depression is in the Public domain.

Figure 4.4 Photo of Chicago 1930s is in the Public domain.

Figure 4.5 Photo from the “I Feel Pretty” musical number from West Side Story.

In the 1950s and 1960s, many cities in the United States saw an increase in juvenile gang activity. The actions of gangs not only were a main focus in the media but also in popular culture with West Side Story (figure 4.5) and in S.E. Hinton’s 1967 publication of The Outsiders which later became a movie. During this era, criminologists turned their focus to opportunities we have in our everyday lives to commit crimes, tying their theories to gang activity and delinquency.

Differential Opportunity Theory

Criminologists Richard Cloward and Lloyd Ohlin (1960) combined Merton’s strain theory with Sutherland’s differential association theory (which will be discussed later in this chapter) to create differential opportunity theory. The focus of differential opportunity theory is on the discrepancy between what the lower-class juveniles desire and what means are available to them because they have fewer opportunities than their peers in other neighborhoods.

Like Merton, Cloward and Ohlin emphasized cultural goals and the means to achieve those goals. However, they added to Merton’s strain theory by suggesting that people’s access to both legitimate and illegitimate means is socially structured. In other words, when looking at obtaining cultural goals, different people have different opportunities (some have more legal opportunities; some more illegal). For instance, in some neighborhoods, there are more opportunities to participate in illegitimate means to achieve one’s goals. The most common of these means is selling illegal drugs. Even though the risk is high, the payoff for many is higher. They see this as an opportunity to achieve their goal rather than pursuing a more conventional method.

This theory focuses on the gap between what an adolescent wants and what they can legally get. The larger that gap, the greater their likely exposure to illegitimate means and willingness to use those means to get what they want. Cloward and Ohlin (1960) said this is evident when there are differences in access to learning structures (those that teach certain values and skills) and performance structures (those that reward delinquent or non-delinquent behavior based on those values and skills). They argue the social structure of the community is responsible for creating more access to legitimate opportunities than illegitimate ones, especially in lower-income communities.

Routine Activities Theory

Routine activities theory sees crime as a function of people’s everyday behavior. For a crime to be committed, there needs to be three elements: a suitable target, a motivated offender, and an absence of guardianship (Cohen & Felson, 1983). This theory claims, for example, that crime will occur when the motivated thief is present near an easy target that is not adequately protected.

One of the most common robbery targets used to be convenience stores. They were seen as easy targets because they always had an amount of cash on hand and for a motivated offender, it was the perfect location to get quickly in and out without getting caught. However, with the help of a convicted person who used to rob convenience stores, store owners learned new strategies and changed into what we see today. Having video cameras filming at all times, a time-locked safe, and even a ruler on the door so that the clerk could give the police a more accurate height estimation were all changes that helped to make the convenience store less of a suitable target because of the creation of guardianship in the store.

Guardianship is measured by the extent to which people during the course of their daily lives protect their property, themselves, and others from crime. Reasons for reduced guardianship have been linked to the fact that because of work and maybe even vacation, our property is often left unguarded. Having a doorbell that also records video can be seen as a significant change in guardianship when it comes to home safety.

Routine activities theory can explain a variety of deviant acts as well as help to understand some changes in crime rates. Osgood et al. (1996) found that in a survey of 18- to 26-year-olds, the time spent in unstructured socializing with peers in the absence of authority figures led to an increase in delinquent behavior, illicit drug and heavy alcohol use, and dangerous driving. A lack of structure creates more time to participate in delinquent behavior and the presence of peers makes that behavior more rewarding.

Routine activity theory looks at the lifestyle and behavioral patterns of individuals to determine their risk of criminal or delinquent behavior in our society. However, there is criticism of this theory as being a “victim blaming” theory since instead of looking at the motivated offender, the theory can focus on the victim and what the victim could have done differently to avoid being victimized. Everyone has the right to live a non-victimized life, but there are behaviors such as excessive alcohol and drug use, walking in non-populated areas at certain times, and even leaving your home that have been shown to create a suitable target.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, crime fell 23% in the first month of the lockdown and that drop was seen to be directly related to the population’s mobility. Business closures and stay-at-home orders meant that there was a decrease in people who were outside of their homes. During the pandemic’s restrictive times, home burglaries dropped but commercial burglaries and car thefts rose. It could be said that the motivated offenders needed to find a suitable target that wasn’t guarded, so cars and businesses became the focus. Residential burglaries decreased by 24% while non-residential burglaries rose 38%. Since people weren’t leaving their homes, cars stayed parked for a longer period of time, and in some cities, the rate of car thefts doubled during the pandemic.

Licenses and Attributions for Opportunity Theories

“Opportunity Theories” by Curt Sobolewski is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 4.5 Photo by Fred Fehl, New York, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

References

Introduction to Criminology Copyright © by Taryn VanderPyl. All Rights Reserved.