5 Ch. 5 Psychological Theories of Crime

Curt Sobolewski and Jeff Bry

Ch. 5

Psychological Theories of Crime

A special thank you to OpenOregon for use of their material. https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/criminologyintro/chapter/5-1-chapter-overview-and-learning-objectives/

Figure 5.1 Picture of primary school children in a classroom.

In 2018 in Texas, a 10 years old boy with autism was pinned down and cuffed for being disruptive and swinging a computer mouse near other students. In 2021 in Colorado, an 11 year old Hispanic boy with autism was cuffed and dragged from the school to be thrown into the back of a police car where he was left for hours for poking another student with a pencil. In 2021 in Maryland, an officer handcuffed and screamed at a 5 year old African American boy for wandering away from his kindergarten class. In 2022 in North Carolina, a police officer pinned down a 7 year old boy with autism for 38 minutes, with a knee on the boy’s neck while placing handcuffs on his tiny wrists. This boy was accused of spitting at a teacher. These are just a few of the many disturbing stories about youth with disabilities and youth of color being mistreated by those in positions of authority who are labeling them as criminals.

The juvenile justice system was designed to help kids living in neglectful and poor conditions. As it has grown over the years, it has gone from a system designed to get children off the streets and stop them from committing petty crimes to a system incarcerating startling numbers of kids with disabilities and racial minority youth. Studies show as high as 85% of incarcerated youth have disabilities and 70% are youth of color (National Council on Disability, 2015; Southern Coalition for Social Justice, 2014). This is a phenomenon seen previously in our nation’s history as well. As discussed in Chapter 3, the positive school of criminology blamed criminality on physical and mental characteristics or disabilities. Today, however, children with disabilities, especially if they are also of a racial minority, are being incarcerated for supposedly different reasons.

After the school shooting at Columbine High School in 1999 and continuing after more recent shootings like the one at Sandy Hook Elementary School in 2012, schools have instituted zero-tolerance policies and upped the presence of police (school resource officers) on campuses. The intent was to create a safer environment for all students, but the unintended consequence is that school infractions have been criminalized. For example, behaviors such as disorderly conduct or anger control issues can be criminalized as assault. The instances that occur in the classroom or on school grounds can lead to arrest or detention by police officers. As a result, kids with disabilities and BIPOC youth have been swept up in a system of criminalization instead of protection. Even though their behavior may be caused by a disability and not actual defiance or dangerousness, it can be misunderstood, and the child is treated like a threat.

This act of punishing children for having disabilities is not new. In fact, it is one in a long line of examples of trying to figure out what is “wrong” with people and what to do about it. Often, the answer has been to lock them away from the rest of society so they can no longer be a problem. This chapter will review some of the theories behind such actions.

Figure 5.1 Picture of primary school children in a classroom, US Department of Education, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 5.3 Photo of American psychologist Henry Goddard (1910s).

Henry Goddard (figure 5.3), was a very popular American psychologist, eugenicist, and segregationist. He began his notorious work with the French Binet-Simon IQ test, translated it, and modified it for his own purposes in the United States in 1914. There are a couple of key points to keep in mind as you read about Goddard’s work. One is that his work was read by Adolf Hilter and was used as justification for many of the atrocities committed by Nazis in Germany. The other important point is that Goddard himself later came out to say his findings and recommendations were wrong. Unfortunately, it was too little too late for millions of people.

Goddard advocated colonizing (isolating, incarcerating, or institutionalizing) and sterilizing people he deemed to be “mental defectives.” He provided “research” to support his eugenic beliefs using his updated IQ test. In 1912, he published the study titled The Kallikak Family: A Study in the Heredity of Feeble-Mindedness that was discussed in Chapter 3. He later admitted his study was deeply flawed, but this was after the results had already influenced future research and even policy. Causing further harm, Goddard, having spent time with youth offenders, claimed that at least half of criminals are mentally defective. In this manner, he created the supposed link between intelligence and crime.

This claim was challenged in 1926 by criminologist Carl Murchison, who maintained that intelligence was not a factor in the causation of crime. Then in 1929, American psychiatrist M.H. Erickson conducted a larger study and discovered a link between IQ and crime, but his research showed that some crimes require a greater IQ than others. What made Erickson’s study different was that he believed that the link between IQ and crime was indirect and that intelligence did not appear to be a causal factor in producing criminals in society.

Then, in 1931, sociologist Edwin Sutherland published a study that contradicted the possible connection between IQ and crime. Sutherland compared the IQ scores of adult offenders to those of army draftees and the two groups had nearly identical IQ levels. The army draftees represented the general population which is something the previous studies failed to measure and then compare. Sutherland argued that if the average IQ of the general population was not known, then it would be impossible to claim it has any effect on human behavior. He concluded that intelligence was not a generally important cause of delinquency (Sutherland, 1931). In spite of Sutherland’s research, the debate over the link between IQ and crime continued for the next forty years.

Contemporary IQ-Crime Connection

In 1961, psychologist Arthur Jensen divided intelligence into two different categories: associative learning and conceptual learning. Associative learning is the simple retention of input or the memorization of facts and skills, for example when you study for an exam and memorize facts you know will be on the test. Conceptual learning is the ability to manipulate and transform information input or problem-solving, such as when that same test has open-ended questions that ask you to think critically about a challenge and offer up possible solutions.

Jensen tested children of racial minority groups in the 1960s and reached two conclusions. First, Jensen concluded that 80% of intelligence is genetic and the remaining comes from the environment. This finding looked directly at the “nature versus nurture” debate, with Jensen arguing that nature (genetics) had more influence on intelligence than nurture (the environment in which a child is raised). Second, he claimed that while all races were equal in terms of associative learning, conceptual learning occurred with a significantly higher frequency in White children compared to Black children. This research led Jensen to problematically conclude that Whites were inherently more able to engage in conceptual learning than Blacks.

In 1967, Nobel laureate and physicist William Shockley stated that the difference between African American and European American IQ scores was because of genetics. This raised a question that has been present in society on the connection between race and intelligence, which later led to the believed connection between crime, race, and intelligence. Shockley (1967) stated that genetics might also explain the variable poverty and crime rates in society.

Working off of Jensen’s findings, sociologist Robert Gordon saw a parallel between IQ scores and delinquency rates revealed in juvenile court records and commitment data. Without much supporting data, Gordon argued that a connection existed between IQ and delinquency in both African Americans and Whites (1976). He concluded that the Black-White IQ difference was essential to address when looking at crime in society and was more important than links between IQ and socioeconomic status.

In a review of research literature, sociologists Travis Hirschi and Michael Hindelang found a small but consistent and reliable difference between the IQs of delinquents and the IQs of non-delinquents. In the studies they reviewed, it was concluded that IQ was an important link to delinquency and that it was more closely related to delinquency than to race and social class. In other words, within social classes and racial groups, persons with low IQs were more likely to be delinquent compared to those with higher IQs. Hirschi and Hindelang connected this finding to school experiences, finding those with lower IQs had negative school experiences and low performance making them more likely to commit delinquent acts (Hirschi & Hindelang, 1977).

The Bell Curve and the Question of Race

In 1994, psychologist Richard Hernstein and political scientist Charles Murray published what soon became a controversial book called The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life. In the book, they concluded that low IQ was a risk factor for criminal behavior. In particular, they claimed the more experience White males had in the criminal justice system, the lower their IQ. Hernstein and Murray suggested that low intelligence could lead to criminal behavior by being associated with the following experiences:

lack of success in school and the job market

lack of foresight and a desire for immediate gains

unconventionality and insensitivity to pain or social rejection

failure to understand the moral reasons of law conformity

They argued that it was cognitive disability rather than economic or social disadvantage that created crime. Because of this, they stated policy should focus on cognitive problems instead of social problems such as unemployment and poverty.

Hernstein and Murray’s study received criticism because of their outdated views of intelligence and the claim that it was difficult to increase IQ scores despite contrary evidence. They explained high crime among African Americans in terms of inherited intellectual inferiority. What Hernstein and Murry failed to consider were the alternative criminogenic risk factors that could exist. By portraying offenders as criminals because of cognitive disadvantage, their research justified repressive crime policy that focused primarily on the individual and not the environment.

It is important to note the research and theories making claims about intelligence and race have been determined to be racist and misleading.

Lifestyle Theory

Forensic psychologist Glenn Walters formulated lifestyle theory as a prison psychologist at the U.S. Penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kansas. Lifestyle theory centers on the belief that criminal behavior is a general criminal pattern of life that is characterized by an individual’s irresponsibility, self-indulgence, negative interpersonal relationships, impulsiveness, and the willingness to violate society’s rules (Walters, 2000). Lifestyle theory concentrates on the development of criminal thinking patterns and was designed to help human service professionals change criminal thinking in their clients.

The three concepts of lifestyle theory are conditions, choice, and cognition. The assumption is that a criminal lifestyle is the result of choices, which can be influenced by biological and/or environmental conditions. Walters’s theory emphasized impulsiveness and a low IQ as the most important features guiding choice and behavior. Further, he also described the cognitive styles that people develop as a consequence of their biological and/or environmental conditions as well as the choices they make in response to them. According to the theory, criminals display thinking errors, such as cutoff, where they discount the suffering of the victim, and power orientation, where they view the world in terms of strengths and weaknesses.

Walters asserted that criminality is the result of irrational behavioral patterns that result in faulty thinking patterns which begin from the consequences of choices made early in life. The early behavioral patterns that exist can extend into criminal behavior later in life because of faulty logic and unrealistic rewards.

Personality Theory

German-British psychologist Hans Eysenck created criminal personality theory to explain criminality by mixing behaviorism, biology, and personality. His goal was to explain the links between personality and crime. He suggested that certain inherited characteristics make crime more likely, but he did not believe that crime was an inherited trait.

Eysenck argued that control of behavior was divided into two categories: conditioning and inherited. Conditioning is the category of personality traits and behavioral characteristics people learn and inherited is the category of those that are genetic. He believed that personality depends on four higher-order factors: ability, extraversion, neuroticism, and psychoticism.

Ability is the innate intelligence everyone has at birth.

Extraversion is an individual’s energy levels that are directed outside of themselves that can be manifested as impulsive sociability.

Neuroticism is a trait associated with depression, anxiety, and other negative psychological states.

Psychoticism can make the individual appear aggressive, impersonal, impulsive, and lacking empathy for others.

While he claimed ability was important in the understanding of crime, Eysenck believed the other three factors were more critical predictors. Eysenck’s criminal personality theory claimed that there were two personality types that had the greatest tendency for criminal behavior: neurotic extroverts and psychotic extroverts. Neurotic extroverts require high stimulation levels from their environments and their sympathetic nervous systems are quick to respond. Psychotic extroverts are cruel, insensitive to others, and unemotional. Most of Eysenck’s work has since been rejected, but that did not stop his influence on others.

Licenses and Attributions for Crime and Intelligence

“Crime and Intelligence” by Curt Sobolewski is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.2 Image of IQ bell curve, Alessio Damato, Mikhail Ryazanov, is in the public domain, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 5.3 Photo of American psychologist Henry Goddard (1910s) is in the public domain, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

In this section, we will examine social learning theory from a psychological perspective. This involves also diving deeper into what motivates a person to behave in a certain way. Crime prevention practices tend to center more on rational thought and the belief that people understand punishment is bad, so they will not complete the act. However, when criminal behavior occurs because the person committing the act thinks of it more in terms of the positive reinforcement they receive from committing the crime based on what they have seen through observation and action during the course of their lives, that goes against the way prevention had been planned.

Psychological Social Learning Theory

Canadian-American psychologist Albert Bandura (1974) defined observational learning as the process by which “people convert future consequences into motivations for behavior.” In other words, people learn by watching others and observing the results of their actions. The unique part of Bandura’s theory was that he argued observational learning did not require direct reinforcement. This is because humans are capable of learning vicariously through the experiences of others or even through their own imaginations.

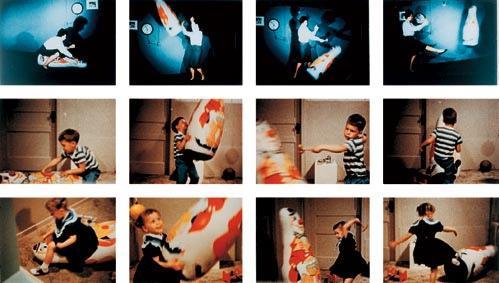

Bandura centered his research on learning aggression. His famous Bobo Doll study involved children who watched an adult attack a plastic clown punching bag named “Bobo,” and then they were rewarded with sweets and drinks for their behavior. Later when the children were in the room with other toys, they chose to attack the doll in a similar fashion as the adults (figure 5.4).

Figure 5.4 Albert Bandura’s Bobo Doll Experiment.

Bandura identified four steps in the process of observational learning: attention, retention, reproduction, and motivation. First, the learners observe what is happening (attention) and then remember the actions they observed (retention). Later they reproduce the model’s behaviors (reproduction) and comprehend and appreciate the possible positive reinforcements that account for the modeled behavior (motivation). When the children watched the adults attack Bobo and then get rewarded, they saw and remembered, then repeated the behavior to get the same result.

Bandura saw family members, members of one’s subculture, and models provided by the mass media as primary teachers in observational learning. Even though the research has never produced a direct link between violence on television and any long-term violent behavior in individuals, Bandura was a frequent critic of the violence that appeared on television and in movies. Although research has failed to produce a long-term connection between exposure to violent material and individual violence, there is a clear relationship that exists when looking at the short-term effects among those individuals who were already aggressive (Freedman, 1986).

Bandura was one of the first theorists to see the direct link between observation and aggressive behavior. His belief and that of those who subscribe to his theory is that among individuals who are already aggressive, observing aggression will influence future aggressive behavior. Thus, as a society, we should not be worried about all children when it comes to watching or being exposed to violent behavior in the mass media and popular culture, but rather focus on those children who already have displayed aggressive tendencies.

In today’s society, we may be able to employ Bandura’s theory when it also comes down to verbal violence on social media. The concept of an “internet troll”—an individual who aggressively attacks someone verbally online—is fairly new in our society. This behavior can be modeled and copied by anyone since online anonymity can allow individuals to act in antisocial manners they would never behave in during face-to-face meetings. Whether it is in social media or online gaming, the behavior that is exhibited by others isn’t necessarily their own unique behavior but rather behaviors they have observed and adapted because they see others get away with it.

5.4.2 Operant Conditioning

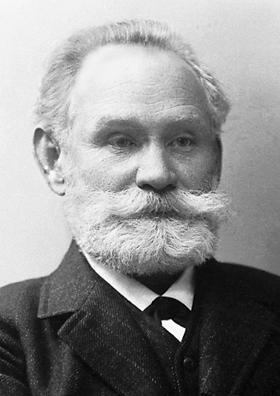

Figure 5.5 Photo of Ivan Pavlov (1904).

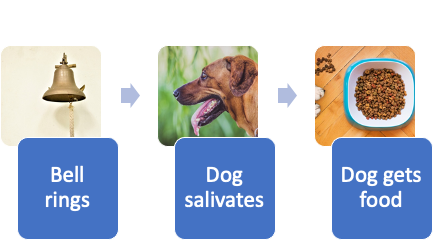

You may have heard of Pavlov’s dogs. It is unusual for someone’s work from the 1900s to have been so popular that it is still commonly referenced today. Nobel Prize winner Ivan Pavlov (figure 5.5) conducted research that resulted in his theory on classical conditioning. In fact, what he learned is still used in dog training today (and in some human training). Pavlov was studying behavior and how to control it (behaviorism). If you have a dog, most likely you have experienced the stimulus-response connection Pavlov found in his research. The belief of classical conditioning is that certain responses are natural and do not require learning. Dogs will salivate when they see food, for example. However, Pavlov discovered that these natural responses can be manipulated. He got dogs to salivate in response to a neutral stimulus (the ringing of a bell), which produced no response until the dog learned to associate it with food. In other words, the bell is rung, the dog is given food and this is repeated. After time, when the bell is rung the dog associates a ringing bell with food so they start to salivate even though no food is present (Figure 5.6).

Pavlov’s operant conditioning led to further research on behavioral conditioning involving humans. In particular, psychologist B.F. Skinner challenged Pavlov’s findings with his theory of operant conditioning. Skinner took the basics of Pavlov’s experiment of connecting a neutral stimulus (the bell) to positive reinforcement (the food). He expanded to look at both good and bad stimuli and also good and bad reinforcements figure 5.7).

Pavlov found this chain of events:

Figure 5.6 Bell rings → dog salivates → dog gets food.

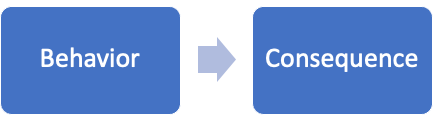

Skinner looked specifically at a chain of events that involved simply:

Figure 5.7 Behavior → consequence.

However, there are different types of consequences and those can make the behavior more or less likely to occur.

Let’s first consider what could make a behavior more likely to occur. The consequence for the behavior could be either giving something (positive) or taking something away (negative). For example, a parent could give a child an allowance in exchange for them completing their chores (positive). Conversely, the child could be required to do their chores if they do not want to get grounded (negative). Either way, the chores are more likely to get done because of the presence of positive or negative reinforcements. A reinforcement is a stimulus that increases the probability of a given behavior, such as being paid for correctly performing a job.

The other layer to this scenario that Skinner proposed is that consequences could make behaviors less likely to happen. In this case, the consequence is still giving (positive) or taking something away (negative), but this time what is being given or taken is more of a punishment than a reinforcement. For example, if a child stays out past curfew and their parent grounds them when they get home, they are less likely to stay out past curfew again. In this case, a punishment is given, so it is considered a positive punishment. The consequence could be that a child stays out past curfew so their cell phone is taken away. Since something is being taken away that makes them less likely to stay out past curfew again, this is called a negative punishment.

Operant conditioning involves the repeated presentation or removal of a stimulus (consequence) following a behavior to increase or decrease the probability of the behavior (Skinner, 1974). Skinner believed different results would occur through the status of the stimulus (whether it was there or not) as well as whether or not the behavior was punished (bad) or reinforced (good). The table in figure 5.8 shows a matrix of these different options.

|

Consequence |

Reinforcement |

Punishment |

|

Giving something |

Positive Reinforcement (getting a reward) |

Positive Punishment (getting something bad) |

|

Taking something away |

Negative Reinforcement (taking away something bad, avoiding bad) |

Negative Punishment (removal of something good) |

Figure 5.8 Matrix of behavior and consequence options in operant conditioning.

Studies have shown that behavioral conditioning is rarely this straightforward and can easily backfire. For example, research has shown that spanking can increase aggressive behavior and that the more you spank a child the more likely they are to defy you (Gershoff et al., 2016). Antisocial behavior and aggression have been linked to excessive use of positive punishment while also this type of punishment may contribute to cognitive and mental health problems. It can teach avoidance behavior and for many create a goal of simply “not getting punished” but not have a replacement behavior available.

In summary, positive and negative punishment is used to discourage inappropriate behaviors while positive and negative reinforcement is used to encourage good behaviors. Some students will study for a big exam not only to avoid a poor grade but also to avoid any form of punishment while maybe getting some reinforcement. The overall key is to replace unwanted behaviors with more acceptable behaviors, which is not always a straightforward process.

The Hierarchy of Needs

On a daily basis, what do you need? Think about how some of your needs may distract you from realizing other needs. For example, have you ever been studying for a big exam and forgotten to eat? Have you prioritized your own education or professional attainment over friendships and family? However, if you are worried about your family then possibly that preoccupation will take over your educational goals. In our lives, immediate needs create immediate action. This is the reason why, when personal issues overtake one’s life, other needs suffer.

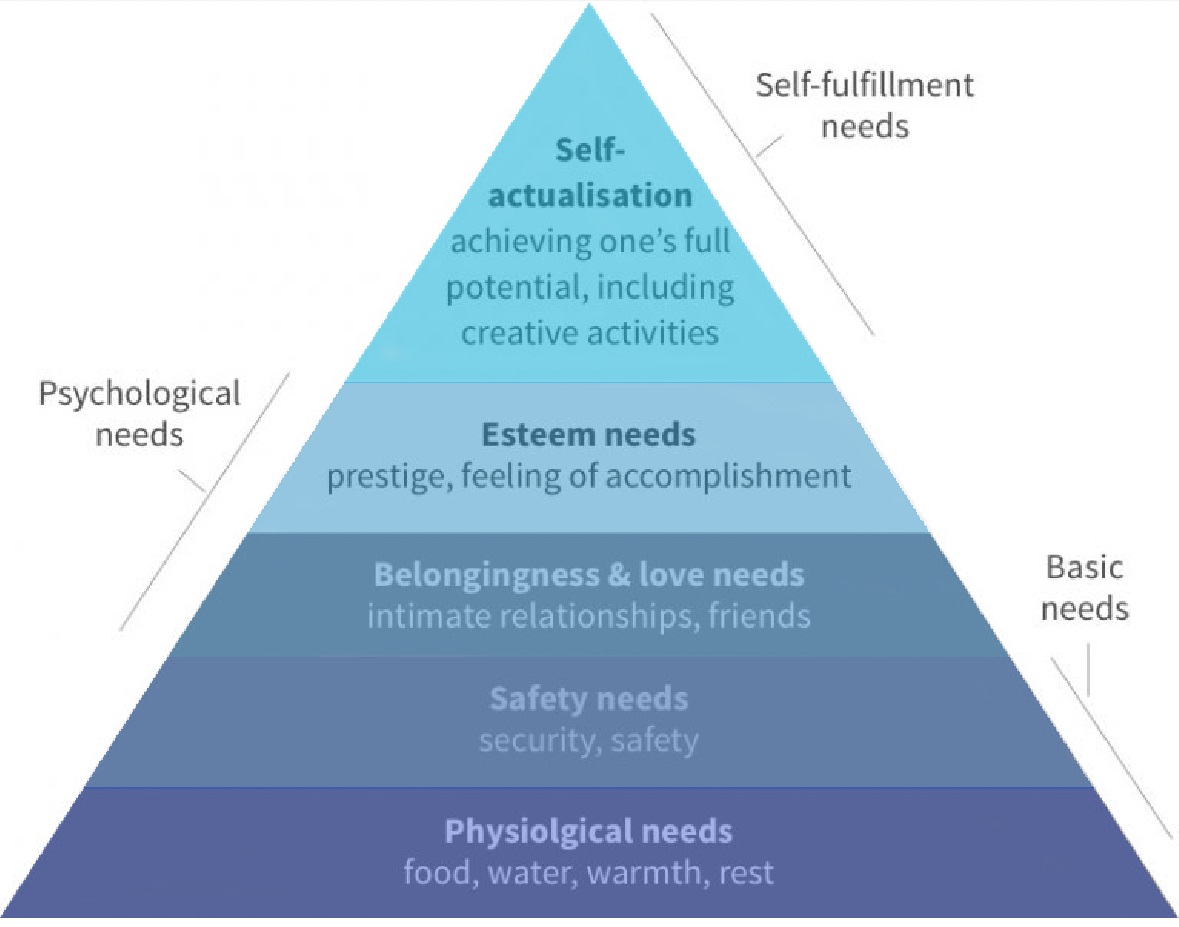

American psychologist Abraham Maslow looked at our needs in connection with what motivates our behavior. He published a paper in 1943 titled “A Theory of Human Motivation” where he introduced the hierarchy of needs table that is presented in figure 5.9.

Figure 5.9 Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

Maslow believed that humans are motivated by goal accomplishment and that one’s needs are mentally prioritized in order of importance. However, the hierarchy is not designed to be followed one after another, meaning our focus does not move directly from food to security to friends. Rather, simply put, a person’s action focuses on satisfying their lower-priority needs before reaching the higher-priority needs.

Physiological needs must be satisfied first. We need food, clothing, shelter, and sleep. These are basic needs and why individuals who do not have these needs met can require social services to help them meet these basic needs of survival. For example, people experiencing homelessness do not have a basic need met of shelter and often food and water, which affects their motivations and behaviors until those needs are met.

Safety needs are usually environmental. These will include the environment you are currently in whether it be home, school, or any other location. If there are problems at home, one may have issues paying attention to their education or work because their safety needs have not been met. These home issues could be discord in the house, addiction, no parental structure, or even that the area they live in is dangerous with possibly the noise of police cars and helicopters keeping them up at night (thus interrupting their physiological need of rest as well). Structure and predictability are important when acquiring safety. Routines are important and that was one of the reasons why the COVID-19 pandemic was so difficult for many people because we all were forced to discover new routines.

Love and a sense of belonging apply to family and friend relationships. This is sometimes difficult when you move to a new city or school and away from family without having friends yet. However, joining clubs, volunteering, or going to group activities are great ways to create a new community. Research has shown that we need face-to-face interactions to accomplish a sense of love and belonging. One of the biggest issues faced by individuals in prison is not the violence that could be experienced in prison but rather the loss of freedom and connection to family.

Self-esteem centers on respect for others, confidence, respect from others, and accomplishment. Most people are critical of themselves because of the evaluation of their own accomplishments and their potential. Self-esteem can be found in our need to succeed but it also can be fostered by being appreciated or acknowledged by others. When an individual’s self-esteem needs have been met then a person will feel capable and worthy instead of incompetent and unimportant.

The needs that have been discussed so far can be viewed as deprivation needs. Basically, if these needs are not met then the individual will not be motivated to focus on the highest needs in the pyramid of self-actualization. This is a need that focuses on the ability of an individual to realize their own potential. The focus of this need is self-improvement and Maslow suggests that very few individuals ever attain this level. These are individuals who understand realistic goals with regard to their ability and their own path in life. In other words, Maslow claims we are rarely actually our ideal selves. To achieve this highest level, individuals go to therapy, live in the present, and understand what they need to gain a better sense of fulfillment. Maslow would see society’s addiction to social media and technology as a barrier to achieving self-actualization because it takes us out of the present and makes it impossible to be satisfied and mindful in the moment.

How is the hierarchy of needs part of the study of crime? We can look at any undesirable behavior, including crime, as a need that is not being met. Someone has found an alternative route to meet a need that is not being met in a prosocial manner. For example, if someone does not have consistent reliable access to food, they may steal some. This is a basic need that must be met. If someone does not have safe, reliable housing, they may end up living in a homeless camp. Figure 5.10 addresses the issue of housing and whether or not illegal homeless camps actually generate crime.

In short, to decrease criminal behavior it is important for basic individual needs to be met. This belief has been difficult in some areas because it is seen as a “give out” or people being “freeloaders” but in reality, making sure community members have their basic needs met can actually be a strong way to decrease crime in the given community. For example, low-income affordable housing and legal homeless camps and pods can help people obtain those basic needs and be able to move on to meet other important needs in their lives in a legal, prosocial manner.

Activity: Do Homeless Camps Generate Crime?

Figure 5.10 Homeless encampment along city street in Portland, Oregon (2020).

Do homeless camps generate crime? The answer may not be as simple as some might think.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, some cities’ tolerance policies let homeless camps enter more visible areas. Subsequently, mayors of Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, and Portland have all promised to crack down on the camps. But the question is why? Is it just because they are now more visible? The stated concern is an increase in criminal behavior, but are the camps actually generating crime?

On average, just the increase in the number of temporary structures in an area is not associated with an increase in property crime. Even in areas where homeless camps have grown in size, there is still no direct link to an increase in property crime. However, camps are filled with individuals who cannot meet their basic needs. When people are without basic needs, they can turn to drugs to alleviate the discomfort, which can make them addicted and in need of money to support their addiction. This can increase property crime in the area.

If the basic needs are not being met among the population of people experiencing homelessness and that can be linked to crime, what should be done to lower crime or the potential for crime in these areas?

Licenses and Attributions for Social Learning and Motivational Theories of Crime

“Social Learning and Motivational Theories of Crime” by Curt Sobolewski is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.4 Albert Bandura’s Bobo Doll Experiment by Creative Commons Attribution, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 5.5 Photo by unknown photographer is in the Public Domain, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 5.6 Bell photo by rhoda alex on Unsplash; Dog salivating photo by Mpho Mojapelo on Unsplash; Dog food photo by Mathew Coulton on Unsplash

Figure 5.7 Behavior → consequence

Figure 5.8 Matrix of behavior and consequence options in operant conditioning by Curt Sobolewski is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.9 Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs by Chiquo, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 5.10 Homeless encampment along city street in Portland, Oregon (2020) by Creative Commons Attribution, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Crime policy is based on the common belief that humans have free will and “choose” to break the laws; and because of this free will, they should be punished accordingly. But, what if we are born with a propensity to offend? What policy could be created for offenders who were born criminals?

Psychodynamic Theory

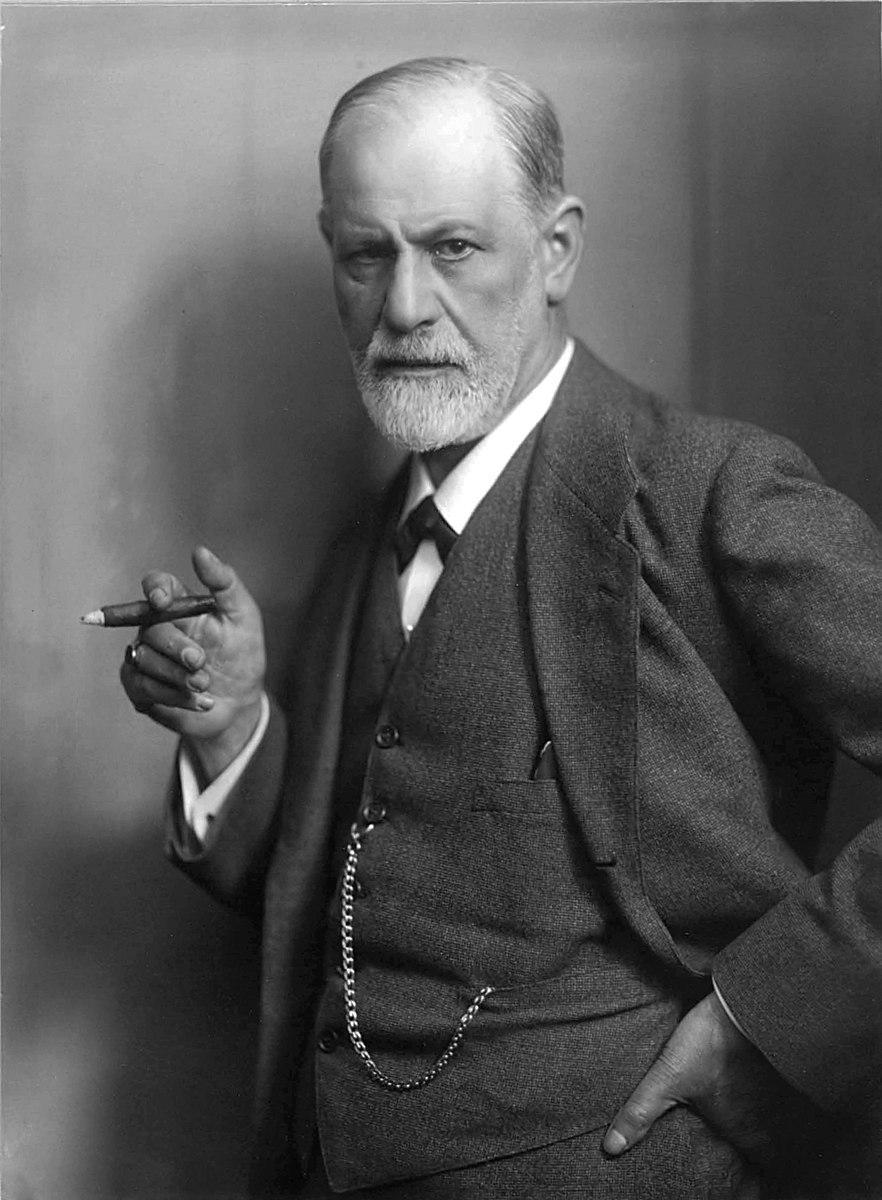

Figure 5.11 Sigmund Freud (1921).

Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud (figure 5.11) developed psychodynamic theory (which is technically a collection of theories) and psychoanalysis (the therapeutic application of the theories) to explain the source of human behavior. Psychodynamic theory is formed around the following basic assumptions:

Unconscious motives drive our feelings and behavior.

Our feelings and behaviors as adults are rooted in our childhood experiences.

We have no control over our feelings and behaviors since they are all caused by our unconscious that we cannot see.

Personality is made up of the id (primitive and instinctive), ego (decision-making), and superego (learned values and morals).

A classic example of Freud’s psychoanalytic theory is the Freudian slip or slip of the tongue. According to Freud, that is a revelation from our unconscious and should be believed.

Psychoanalysis applies psychodynamic theory in therapy by examining one’s childhood and trying to better understand your unconscious. Freud believed the unconscious was able to alter one’s conscious values and emotions without the individual being aware of this control. According to Freud, individuals are not aware of what determines their behavior and this is in contrast with the concept of “free will” that was part of the classical criminological theories discussed in Chapter 3.

According to Freud, the unconscious is where unpleasant memories and explosive emotions exist and these both are accumulated as repressed memories and emotions. In other words, what has happened to us in the past can guide our behavior even if we aren’t aware of the connection. We may also be willing to use illegitimate means to get what we want, much like in Merton’s strain theory covered in Chapter 4. According to Freud, in order to help someone change their behavior, it is essential to access and understand their repressed memories, which is again where psychoanalysis comes in.

The Psychopath Test

Are you a psychopath? Well, there is a test you can take to determine if you are. Do not worry if you are because that could just mean that you would become a good CEO of a company. Research has shown that CEOs tend to score high on the psychopath test (Wisniewski, Yekini, & Omar, 2017).

Psychopathy has connections to the study of crime that go back more than 100 years. Many people think of serial killers and people who commit heinous crimes when they think of psychopathy, although we now know it is also common in people who are especially successful in business. Someone who is a psychopath does not have feelings of remorse. Psychopathy is a personality disorder characterized by narcissism and manipulation. Psychopaths may be cold-blooded and violent, but they also know how to use charm to attain their goals.

Early researchers saw psychopathic behavior as moral insanity. The term psychopathic was first used in 1894 by German psychiatrist Julias Ludwig August Koch who studied personality disorders. He viewed people who had emotional and moral aberrations derived from congenital factors as suffering from psychopathic inferiority. Research on psychopathy has continued over the years and has seen several iterations. German Psychiatrist Emile Kraepelin expanded upon Koch’s research in 1904 and created categories of psychopathic personality while also bringing back a moral component to psychopaths. His categories included born criminals, pathological liars, querulous persons (someone who always feels wronged), and persons driven by basic compulsion (such as addicts).

Another German psychiatrist Kurt Schneider continued the work on psychopathy in 1923. He argued there are many types of abnormal personalities that are not harmful. The important distinction, according to Schneider, is that psychopathic personalities suffer from their abnormal personality and cause suffering to others because of it. He identified ten types of psychopathic personalities such as fanatics, emotionally unstable, explosive, insecure, attention-seeking, affectionless, and more. Schneider’s 10 types of psychopaths are the foundation for the later developments over decades of studying the human mind and the connection between what we think and how we act.

Contemporary classifications of psychopaths create a more general vision of psychopathic behavior. Psychopathy in the official psychiatry diagnosis manual (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition; DSM-V) is associated predominantly with boldness, meanness, and disinhibition. The general notion of someone who is a psychopath is one who is charming and makes a good first impression, but actually has a complete lack of empathy and will demonstrate aggression and behaviors that are harmful to others.

In 2011, John Ronson wrote the book The Psychopath Test: A Journey Through the Madness Industry in which he explored the idea that psychopaths may not only be criminals but leaders of corporations and politicians in our society. Ronson brings up a very interesting question when looking at behavior in our society: “what is normal behavior?” The CEO of a company who fires a group of workers right before a holiday may be just doing their job and be seen as a strong leader, but does this CEO feel any emotion for changing these workers’ lives? Any for ruining their holiday plans? If not, then could this CEO be a psychopath? This type of behavior occurring in a normalized setting of ruthless behavior does not change the definition of the behavior itself, but rather shows how society views the individual.

Activity: A Forensic Psychologist Test for Psychopathology

Forensic psychologists work within the legal system to translate medical psychological terminology into legal language. They evaluate the current state of the individual and provide treatment and sentencing recommendations. The forensic psychologist will conduct psychological assessments of the individual which include tools such as tests, interviews, behavioral observations, and case studies. These tests can help in understanding the psychological and mental health status of the individual and focus on anything from depression to psychopathy.

Psychopathy can be tested through Forensic Assessment Instruments (FAIs), Clinical Assessment Instruments (CAIs), and The Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R) which is the most frequently used tool in violence risk assessment, civil commitments, and insanity evaluations.

Vilijoen et al. (2010) surveyed 199 forensic clinicians about the practices they used in assessing violence risk and found that the use of risk assessment and psychopathy was common. Even though the psychopathy measures were used more with respect to adults, the researchers found that the majority of clinicians (79%) used the measure with juveniles at least once. The issue in this situation is the labeling of juveniles as psychopaths and the long-term effects that would have on their lives. If a juvenile is labeled as a psychopath then this could affect their length of detention and if they are in the adult system then their chance of early release becomes less likely with a label of “psychopath.”

If a person is labeled as a psychopath then can they be helped through therapy or are they simply labeled a psychopath for the rest of their lives?

Antisocial Personality Disorder

Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD) is a condition where the subject has been poorly or ineffectively socialized which leads to behavior which puts them in consistent and constant conflict in society. Individuals with ASPD are self-centered and selfish, impatient, impulsive, calloused and noxious towards others, they also do not feel guilt or remorse for their behavior. Individuals with ASPD do not learn from experience and punishment, they are intolerant of others needs and cannot handle frustration. Other characteristics of this disorder include lacking in empathy towards others, very high sense of self-worth or capability, many are able to replicate superficial charm.

An individual with ASPD may not necessarily choose to commit crimes, but their personality and approach to life makes their lives seemingly difficult. They have difficulty in maintaining relationships including friendships and romantic relationships, they also have a difficult time maintaining employment and completing the basic tasks of life (bills, meetings, being social, etc.). As these individuals are extremely selfish and self-centered, they tend to mainly think of themselves and not consider the wants and needs of others. They may also see crime as an “easier” alternative to working a full-time job, they also do not feel guilt or remorse for their actions and behaviors. These attributes are what generally results in a higher risk and propensity to be involved in crime.

In a Student’s Own Words:

Question: What are the characteristics of people with antisocial personality disorder?

“People diagnosed with Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD) often show a consistent pattern of behavior that includes a lack of concern for others, impulsive actions, manipulation, and a disregard for societal rules. These characteristics can increase the likelihood of partaking in criminal behavior.

One of the main features of ASPD is the absence of empathy, which allows people to harm others without feeling guilty. Most people are discouraged from harmful actions due to their emotional connection with others. However, people with ASPD do not experience this emotional barrier, making it easier for them to commit crimes without any internal conflict.

Moreover, the impulsiveness associated with ASPD can lead people to engage in criminal activities without considering the legal consequences. Their inability to think through the potential consequences of their actions can result in impulsive acts of violence, theft, or other criminal behaviors.

The manipulative tendencies observed in people with ASPD can also contribute to their involvement in criminal activities. Their ability to deceive and manipulate others can lead to fraudulent activities. They may use the trust of others for personal gain, disregarding the harm they cause in the process.”

The Psychotic Offender

Some forms of crime and criminality may be the result of some aspect of psychosis. Psychotic individuals generally have psychological conditions and issues that put them out of touch with reality. These individuals may experience delusions, hallucinations and/or other significant breaks and disjunctions with reality. While these conditions are not necessarily related to crime, this disjointed thinking may propel people into criminal acts based upon breaches of reality that result in inappropriate and/or criminal behavior.

An example of this breach in reality would include schizophrenia. Schizophrenics have disordered and disjointed thinking that puts them out of touch with reality. Paranoid Schizophrenics possess disjointed thinking INCULDING delusions and hallucinations. While these conditions do not necessarily result in criminal behavior, a schizophrenic may misinterpret situations and/or reality in such a way as to commit crimes. This could be based on overt actions, or reactions to people and situations their disorder misconstrues or misinterprets, le

The Lucifer Effect

For centuries, researchers have been trying to understand how people could commit deplorable acts and why they would do so. After World War II, social psychologists tried to discover why such a horrible event as mass genocide happened and how so many people chose to participate. Psychologist Solomon Asch conducted a study on conformity in the 1950s. His study focused on a “vision test” where a group of students was asked to look at three lines and decide which line matched the length of the reference line. What he was really studying is whether participants would change their answers to match (conform) with others in the group. Asch found that 75% of the participants conformed at least once, and 5% conformed every time. Asch’s study showed how conformity is over-trained in our educational system. Think back to elementary school and how conformity was rewarded. We are taught to conform and, as a result, going against a group is difficult for most.

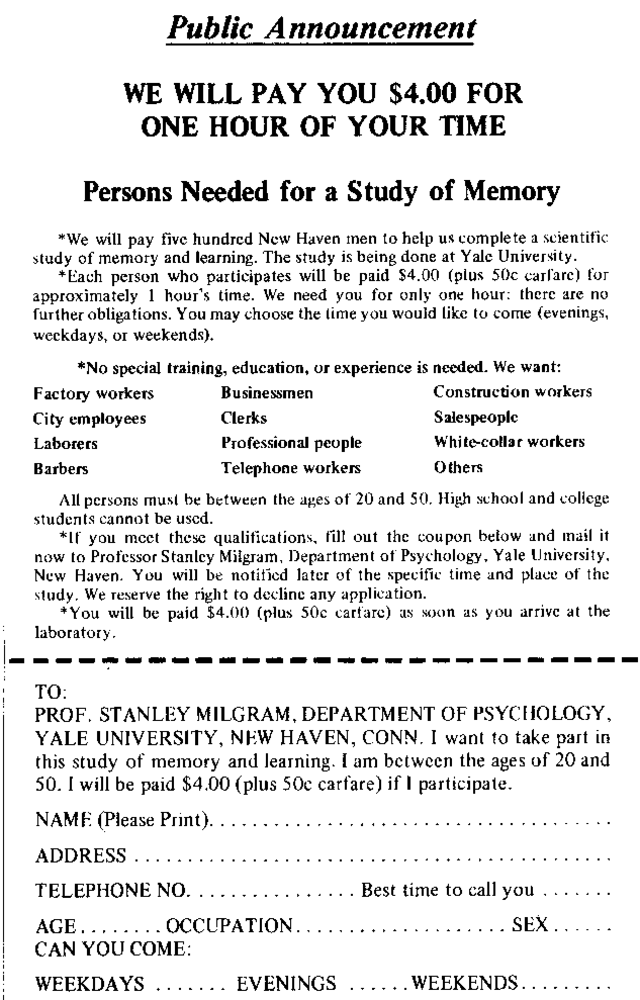

Despite these findings, critics did not think that Asch’s study got at the core of Nazi Germany’s genocide since it was only looking at lines and the decision was not actually about life or death. These critics were challenged by Stanley Milgram’s experiment on obedience (Figure 5.12). By far the most famous conformity research, Milgram began his experiments in 1961 and tried to answer the question of whether or not many of the Nazis were just following orders and being obedient.

Figure 5.12 Advertisement for the recruiting of the Milgram experiment subjects (1961).

The experiment setup was simple. There was a teacher and a learner. Unknown to the “teacher,” the “learner” was a plant in the study (an actor) and knew what was going on. The teacher would read a list of words and the learner had to recall a particular pair from a list of four possible choices. If the learner missed an answer, the teacher was supposed to give him an electric shock. When the teacher paused not wanting to shock the learner (who previously revealed that he was checked out for heart issues) the facilitator of the experiment would say, “The experiment requires you to continue,” and, “It is absolutely essential that you continue,” and finally, “You have no other choice but to continue.” Even after the learner screamed, 65% of the participants in the teacher roles continued to shock the learner up to the highest level (450 volts) and all of the participants in the teacher roles continued administering shocks up to 300 volts. All the teachers shocked the learner at least once.

In his article “The Perils of Obedience,” Milgram (1974) wrote:

The legal and philosophic aspects of obedience are of enormous import, but they say very little about how most people behave in concrete situations. I set up a simple experiment at Yale University to test how much pain an ordinary citizen would inflict on another person simply because he was ordered to by an experimental scientist. Stark authority was pitted against the subjects’ [participants’] strongest moral imperatives against hurting others, and, with the subjects’ [participants’] ears ringing with the screams of the victims, authority won more often than not. The extreme willingness of adults to go to almost any length on the command of an authority constitutes the chief finding of the study and the fact most urgently demanding explanation.

The willingness of adults to conform to authority could only make a person wonder how much of their behavior is due to the participant’s belief that it is what they are supposed to do in the situation they are in. Phillip Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison experiment showed perfectly how quickly individuals would adapt to a given role based on this basic belief.

In 1971, Phillip Zimbardo conducted the infamous Stanford Prison Experiment in which college student participants were randomly assigned the roles of either “guard” or “prisoner.” In this study, the guards quickly began using their power to brutalize and humiliate the prisoners. The experiment was designed to last two weeks, but because of the trauma experienced by the participants, it was stopped after only six days. What caused these normal college students to commit unspeakable acts? Was that what they believed they were supposed to do in that situation or were they themselves evil?

In his 2007 book The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil, Zimbardo sought to explain why people who live “good” lives suddenly engage in “evil” actions. His belief is that the worst criminal behavior could be because an individual conforms to a specific ideology or narrative that tells them those they are harming are not human, they are “others.” This train of thought can be applied to police shootings, school shootings, and all the “evil” actions that are present in our society.

This is what many claim happened in Buffalo, New York on May 14, 2022, when a White man went into a grocery store and killed ten Black individuals. The shooter was motivated by hate and also the White nationalist concept of “replacement theory” which has been supported by some politicians and certain media outlets in the United States. The question could be asked if the one way to prevent mass shootings and police brutality would be to change the narrative that exists from people being the “enemy” or the “other” to everyone being “human.”

Insanity and Legal Definitions

Whether or not an individual has the capacity to stand trial based upon psychological issues or “insanity” defenses has been a long-standing issue. There have been a number of standards for whether or not a defendant is culpable for the crimes they have committed. The M’Naughten Rule is a standard for judging whether an individual is legally sane, requiring the offender to not know what they were doing, or what they were doing was wrong.

The irresistible-impulse test followed M’Naughten Rule, as a judgement for mental sanity and fitness that examines if (because of their mental state) the person could “not resist” committing the crime. This test judges legal sanity on whether or not the individual’s mental fitness made them unable to resist committing the crime.

The Durham Rule is a standard for judging legal insanity based upon the individual not being responsible for their criminal actions based upon mental defect or mental disease.

There also may be an adjudication of guilty but mentally ill (GBMI). This adjudication finds the suspect guilty of the crime, but based upon their prevailing mental condition are generally sent to a state or psychiatric hospital for treatment rather than to prison.

Licenses and Attributions for Nature versus Nurture: Are We Born Bad?

“Nature versus Nurture: Are We Born Bad?” by Curt Sobolewski is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.11 Sigmund Freud (1921) by Max Halberstadt, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 5.12 Advertisement for the recruiting of the Milgram experiment subjects (1961) by Olivier Hammam, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Conclusions

In this chapter, we focus on theories that are all about the individual person and their own behavior. In this chapter, we considered theories of intelligence and personality. Whatever is believed to be the source of criminal behavior guides policies and practices. For this reason, it is important to know the theory behind the decisions. Some of the theories in this chapter were deterministic, meaning people have a certain intelligence or personality and there is not much to be done about that. However, other theories suggested different interventions like conditioning and therapy could help change someone’s behavior. As we discussed in Chapter 1, the point of criminology is to understand why crime happens with the end goal of being able to stop it. Think about how the theories in these chapters affect how people may go about trying to stop crime.

Application Exercises

Take an IQ test. What does it say about your likelihood to commit crime according to the theories discussed in this chapter?

Take a psychopath test. What does it say about your likelihood to commit crime according to the theories discussed in this chapter?

Go through Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and see if your needs are being met and at what level.

Discussion Questions

Is there both good and evil in everyone? What tips the scales in one direction or the other?

Which has more influence on someone’s personality and behavior – nature or nurture?

Does intelligence have any influence on whether or not a person is a criminal? Explain.

Can a person be a psychopath and not a criminal? Explain.

Freud’s theories have been popular, but how do they apply to the study of crime?

How can Maslow’s hierarchy of needs be used to help support policy in our society?

Key Terms

ability

associative learning

classical conditioning

conceptual learning

conditioning

criminal personality theory

cutoff

extraversion

inherited

IQ

lifestyle theory

negative punishment

negative reinforcement

neurotic extroverts

neuroticism

observational learning

operant conditioning

positive punishment

positive reinforcement

power orientation

psychoanalysis

psychodynamic theory

psychopathic

psychotic extroverts

psychoticism

Summary

The average IQ test score is 100. Someone below 85 was considered undesirable and problematic. This label did lead to someone being incarcerated or institutionalized, or even murdered. Goddard advocated colonizing and sterilizing people he deemed to be “mental defectives.” He claimed that at least half of criminals are mentally defective. Murchison maintained that intelligence was not a factor in the causation of crime, but Erickson discovered a link between IQ and crime and claimed some crimes require a greater IQ than others. Several scholars promoted research that made racist claims about IQ differences between African Americans and European Americans. Hirschi and Hindelang found within social classes and racial groups, persons with low IQ were more likely to be delinquent. Hernstein and Murray argued that it was cognitive disability rather than economic or social disadvantage that created crime.

Walters formulated lifestyle theory that centers on the belief that criminal behavior is a general criminal pattern of life. Eysenck created criminal personality theory to explain criminality. Bandura defined observational learning as the process by which “people convert future consequences into motivations for behavior.” Pavlov conducted research that resulted in his theory on classical conditioning and Skinner looked at both good and bad stimuli and also good and bad reinforcements in terms of how they affected behavior. Maslow believed that humans’ needs are mentally prioritized in order of importance. Freud believed the unconscious was able to alter one’s conscious values and emotions without the individual being aware of this control. Koch viewed people who had emotional and moral aberrations as suffering from psychopathic inferiority. Kraepelin created categories of psychopathic personality and Schneider argued there are many types of abnormal personalities that are not harmful. The important distinction is that psychopathic personalities suffer from their abnormal personality and cause suffering to others because of it. Asch conducted a study on the willingness of adults to conform to authority. Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison experiment showed how quickly individuals would adapt to a given role to commit evil acts.

Resources

The American Bar Association provides various resources, such as publications including periodicals and the ABA Journal. http://www.americanbar.org/aba.html

The National Center for State Courts provides information on mental-health courts. https://www.ncsc.org/Topics/Alternative-Dockets/Problem-Solving-Courts/Mental-Health-Courts/Resource-Guide.aspx

PsychLAW is the American Psychological Association website for psychology and law. It links to the APA journal Psychology, Public Policy and Law and to APA amicus briefs. http://www.apa.org/topics/law/index.aspx

Licenses and Attributions for Conclusion

“Conclusion” by Curt Sobolewski is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

References

Introduction to Criminology Copyright © by Taryn VanderPyl. All Rights Reserved.