3 Ch. 3 Crime and Punishment – Law and Classical and Neoclassical Schools

Lore Rutz-Burri; Brandon Hamann; and Jeff Bry

Ch. 3

Classical and Neoclassical Schools

Lore Ritz-Burri

https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/ccj230/chapter/8-1-functions-and-limitations-of-law/.

3.1. Functions and Limitations of Law Copyright © 2019 by Lore Rutz-Burri is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Law is a formal means of social control. Society uses laws (rules designed to control citizen’s behaviors) so that these behaviors will conform to societal norms, cultures, mores, traditions, and expectations. Because courts must interpret and enforce these rules, laws differ from many other forms of social control. Both formal and informal social control have the capacity to change behavior. Informal social control, such as social media (including Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter) has a tremendous impact on what people wear, how they think, how they speak, what people value, and perhaps how they vote. Social media’s impact on human behavior cannot be overstated, but because these informal controls are largely unenforceable through the courts as they are not considered the law.

Laws and legal rules promote social control by resolving basic value conflicts, settling individual disputes, and making rules that even our rulers must follow. Kerper (1979) recognized the advantages of law in fostering social control and identified four major limitations of the law. First, she noted, the law often cannot gain community support without support of other social institutions. [1] (Consider, for example, the United States Supreme Court (Court) case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), which declared racially segregated schools unconstitutional. The decision was largely unpopular in the southern states, and many had decided to not follow the Court’s holding. Ultimately, the Court had to call in the National Guard to enforce its decision requiring schools to be integrated.) Second, even with community support, the law cannot compel certain types of conduct contrary to human nature. Third, the law’s resolution of disputes is dependent upon a complicated and expensive fact-finding process. Finally, the law changes slowly. [2]

Lippman (2015) also noted that the law does not always achieve its purposes of social control, dispute resolution, and social change, but rather can harm society. He refers to this as the “dysfunctions of law.”

“Law does not always protect individuals and result in beneficial social progress. Law can be used to repress individuals and limit their rights. The respect that is accorded to the legal system can mask the dysfunctional role of the law. Dysfunctional means that the law is promoting inequality or serving the interests of a small number of individuals rather than promoting the welfare of society or is impeding the enjoyment of human rights.” [3]

Similarly, Lawrence Friedman has identified several dysfunctions of law: legal actions may be used to harass individuals or to gain revenge rather than redress a legal wrong; the law may reflect biases and prejudices or reflect the interest of powerful economic interests; the law may be used by totalitarian regimes as an instrument of repression; the law can be too rigid because it is based on a clear set of rules that don’t always fit neatly (for example, Friedman notes that the rules of self-defense do not apply in situations in which battered women use force to repel consistent abuse because of the law’s requirement that the threat be immediate); the law may be slow to change because of its reliance on precedent (he also notes that judges are also concerned about maintaining respect for the law and hesitate to introduce change that society is not ready to accept); that the law denies equal access to justice because of inability to pay for legal services; that courts are reluctant to second-guess the decisions of political decision-makers, particularly in times of war and crisis; that reliance on law and courts can discourage democratic political activism because Individuals and groups, when they look to courts to decide issues, divert energy from lobbying the legislature and from building political coalitions for elections; and finally, that law may impede social change because it may limit the ability of individuals to use the law to vindicate their rights and liberties. [4]

Kerper, H. B. (1979). Introduction to the criminal justice system (2nd ed.). West Publishing Company. ↵

Kerper, H. B. (1979). Introduction to the criminal justice system (2nd ed., pp. 11). West Publishing Company. ↵

Lippman, M. R. (2015). Law and society (pp. 11). Thousand Oaks, CA : SAGE Publications. ↵

Lippman, M. R. (2015). Law and society (pp. 25). Thousand Oaks, CA : SAGE Publications. ↵

History of Law

The Code of Hammurabi (1755-1750 BC) is one of the earliest written legal codes. This code defined crimes and sanctions for crimes. Sanctions were often quite punitive, an “eye for an eye” types of sanctions. Punishments were often very severe, with retribution and “revenge” seeking of the victims being a focal concern. There was an attempt to control and regulate outcomes, especially to keep the victims and/or their family from taking the law into their own hands. Sanctions varied by societal position, the elite received lessor sanctions, a low-born person could be killed.

Mosaic Code were the laws given to the Israelites by God. Includes and begins with the Ten Commandments, shall not steal, kill, commit adulty etc. Evidence these were folkways that became laws.

Twelve Tables were the laws of ancient Rome. Laws were created under pressure of lower classes to stop injustice of upper classes. Laws dealt with personal debt, property and family issues, mainly everyday issues.

Many laws were lost during the “dark ages” (500 – 1000 AD). Informal laws took the place of formal laws in Europe. Development of the Wergild system, which means “man’s price.” This system defined what the offender would owe the victim or victim’s family. Guilt in this system was determined using:

Compurgation – The accused would swear an oath of innocence, backed by a credible group of “oathhelpers.” Powerful people could use their wealth and power to find suitable oathhelpers.

Ordeal – Based upon “divine intervention,” the accused would be drowned, dunked in boiling water or lead, or burned. If they were innocent, divine forces would intervene.

Trial by combat was often used as well, either the accused would fight or a “champion” would fight in their place. Benefitted those with military training, wealth and power.

Law in Feudal England (1066) was an attempt to bring about formal law. This law was still fairly informal, still mainly benefitted the powerful.

Contributions included dividing counties into shires, which were overseen by a Shire Reeve (Sherrif).

Shire Reeve enforced the laws but also protected nobility and their property.

A court system was developed; which included a court to hear petty cases (Hundred-Gemot), a court to hear more serious cases that was usually held by local landholders (Shire-Gemot) and a court to hear cases of a religious nature.

English Common Law was an attempt to create a legal system “common” to all citizens. This system made substantial improvements and increased consistency in court hearings and outcomes. Common law was not perfect but gave more rights and a sense of justice to “common” people. Much like the modern legal system, wealth and power can make a difference in dispositional outcomes of defendants.

Present English system of laws. Came into existence during the reign of Henry II (1154 – 1189).

Referred to as “common” because the law applied to all subjects.

Centralized power to king, weakened local court systems in favor of formal “unbiased” court systems.

Developed traveling or “circuit judges”, hearing cases previously heard by local courts.

Use of “juries”, or local landholders to decide facts in cases, investigate crimes, give testimony, accuse offenders.

Eventually turned to “Royal Prosecutors” to present evidence and bring forward witnesses to the trial.

The Magna Carta was enacted on June 15th, 1215 by King John of England. The Magna Carta began as a means to ensure feudal rights, in essence to ensure the king would not encroach on landowner’s rights. The Magna Carta also was initially written to provide guarantees for the freedom of the church.

In 1613 the Magna Carta was interpreted to support individual rights and trials by jury. It was decreed the Magna Carta ensured basic liberties to all English citizens and found the English Parliament could not retract these rights. The Magna Carta also evolved the concept of due process protection for all citizens, not just for royalty or elites. From this perspective the Magna Carta has been viewed as the “foundation stone” of our current rights and liberties.

Modern law in the United States has borrowed heavily from English Common Law. The work of the Enlightenment (Age of Reason) during the 17th and 18th centuries were instrumental to modern rights and protections (due process, etc.) of modern United States law.

Classical School

Mauri Matsuda

https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/criminologyintro/chapter/3-4-classical-school-of-criminology/

“Classic School of Criminology” by Mauri Matsuda is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.3 Elevation, section and plan of Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon prison, executed by Reveley, 1791 is in the Public domain.

During the Age of Enlightenment, many philosophers argued that humans were rational, thinking agents who possessed free will. In this manner, they went against the church that claimed crime was often the result of demonic possession. This new approach brought about a significant paradigm shift in the way people looked at criminal behavior. If crime was the result of rational decision making, it would not be solved through religious intervention or sham trials in which the offender could feel confident the jury would not convict them. A better, more reliable system needed to be developed. It is in this setting the classical school of criminology was established.

The classical school of criminology is not a physical place, but instead refers to the roots of criminological thought in the writings of the philosophers and social reformers who became prominent during the Age of Enlightenment. This was when western societies were revolutionized by the emergence of new institutions of governance and old traditions were replaced by modern values and ideals. These theorists shared the belief that humans were reasoning beings who engaged in conscious deliberation—in other words, their decision-making was guided by self-interest, rationality (weighing the costs and benefits of various courses of action), and hedonism (the desire to maximize pleasure and minimize pain). The classical school of criminology also focused on methods of making the administration of justice, including criminal sanctions, more rational, effective, and efficient.

One of the most important concepts to arise from the Age of Enlightenment was the notion of the social contract. The social contract is the voluntary relinquishment of some freedoms in exchange for order and safety provided by a sovereign, or ruler. It is the social contract that allows the state to govern over individuals. Simply put, we agree to follow laws (giving up our freedom to do whatever we want) for the overall benefit of society. When someone breaks one of the agreed upon laws, they are essentially breaking the social contract.

Cesare Beccaria

One of the most well-known writers from the era of classical criminology is Cesare Beccaria. Beccaria was an Italian nobleman who belonged to an academic salon, or literary society, that debated issues of the day and sought to bring about legal reforms. In 1764, Beccaria published his treatise On Crimes and Punishments, in which he advocated for reform of the criminal justice system, including the elimination of torture, secret accusations, and the death penalty. One of Beccaria’s most important contributions to criminology, however, was his argument that punishment should be utilitarian—in other words, that punishment should serve the greater good rather than simply exact revenge or administer justice.

More specifically, Beccaria believed that the purpose of punishment was to deter crime, an argument that forms the foundation of deterrence theory. Deterrence relies on the fear of punishment to prevent individuals from engaging in criminal behavior. It is one of several utilitarian purposes of punishment, along with rehabilitation (reforming the offender) and incapacitation (physically preventing an offender from committing further offenses by isolating them from society). Utilitarian purposes of punishment contrast with symbolic purposes such as retributive justice (revenge), or the idea that punishment should be inflicted in service of vengeance, often referred to as an “eye for an eye”, or someone getting their “just desserts.”

Beccaria begins by describing the social contract. He claimed punishments are necessary to restrain the innate passions of all individuals, who would otherwise commit crimes to serve their own interests. Punishment, therefore, was necessary to defend the social contract. Any punishment inflicted without a clear utilitarian purpose, however, was considered by Beccaria to be tyrannical.

Beccaria also highlighted the importance of a system of checks and balances. He argued for the separation of powers between executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government. He stressed that the role of judges should be to determine guilt or innocence and apply sentences within the penalties established by the law. Furthermore, he emphasized the importance of codifying laws into written statutes and ensuring the general population could read and comprehend the laws in order to follow them. Ultimately, Beccaria believed that the surest way to prevent crimes was through educating the population. He claimed that as societies increased the literacy and education of their citizens, punishments would naturally become less severe, as more educated citizens would require lesser punishments to be deterred from crime.

The core of Beccaria’s arguments about deterrence is that punishment should be (1) swift, (2) certain, and (3) proportionate to the crime. The immediate nature of punishment (the swiftness) was important for at least two reasons. First, Beccaria believed that deterrence would be more likely if the punishment was paired more closely in time with the commission of crime. Second, Beccaria believed that the anticipation of punishment was nearly as painful as the punishment itself. Thus, a long drawn-out trial period was considered cruel (or as stated by former United Kingdom Prime Minister William E. Gladstone, “Justice delayed is justice denied.”). Beccaria also considered the certainty of punishment the most important element of deterrence—far more important than the severity of punishment. Someone had to believe they really would be punished if they were caught, and that there was no longer a chance the jury would let them off the hook to prove a point. Several research studies show that the actual or perceived certainty of punishment is a greater deterrent to crime than the actual or perceived severity of punishment.

Finally, Beccaria believed that the severity of punishment should be scaled to the severity of the crime. To make the punishment proportionate to the crime, one must consider the level of harm, or injury, to society. In other words, the punishment should “fit” the crime. At the same time, Beccaria also believed that a punishment should only be as severe as necessary to achieve the purpose of deterring crime. Anything beyond that was considered cruel.

Beccaria made many other arguments and his treatise was widely influential to the founding fathers of the United States. He is credited with helping to rationalize systems of justice and law and eliminating barbaric practices. His most important ideas can be condensed with the final entry in his treatise:

That a punishment may not be an act of violence, of one, or of many against a private member of society, it should be public, immediate and necessary; the least possible in the case given; proportioned to the crime, and determined by the laws.

Like other classical thinkers of the Enlightenment era, Beccaria assumed individuals had free will. He also believed that humans were rational, self-interested actors who sought to maximize their pleasure and minimize their pain. These assumptions imply that Beccaria held a specific theory of human (and criminal) behavior. However, Beccaria’s goal was to advocate change, specifically social and legal reforms rather than develop a theory of human behavior.

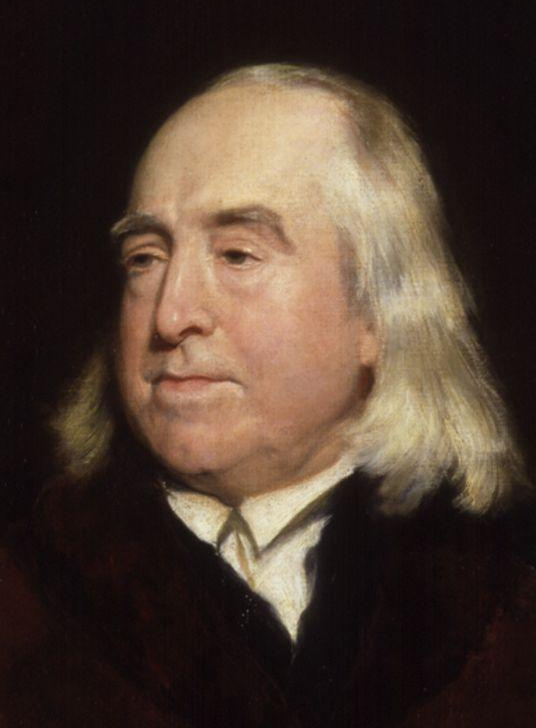

Jeremy Bentham

Following the popularity of Beccaria’s work in 1764, English philosopher Jeremy Bentham published his own proposal for how to address crime and punishment based on the new perspective promoted by Beccaria. In An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (1789), Bentham outlined his own utilitarian philosophy, arguing that “nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure.” According to Bentham, humans were indulgent and self-interested, but also rational. In other words, they would seek whatever promoted their pleasure and prevented their pain. The sources of

pleasure/pain were broad; they could be physical (e.g., violence), political (e.g., legal sanctions), moral (e.g., reputation), or religious (e.g., damnation). These ideas would form the basis for Bentham’s theory to understand and explain human behavior.

Bentham’s ideas of people choosing actions based on pleasure and pain principles.

The purpose of law is to promote and produce happiness in the community it serves.

Punishment is potentially harmful, it is justified according to Bentham if it prevents more harm than it causes. (Social Contract)

Main objectives of punishment

1. To prevent all criminal offenses

2. When it cannot prevent a crime, to convince the offender to commit a less serious crime.

3. To ensure that a criminal uses no more force than is necessary.

4. To prevent crime as cheaply as possible (deterrence).

Torture and Cruel and Unusual punishment are problematic.

Elimination of torture, use of “loss of liberty” as an appropriate sanction

Picture source from pixabay.com

In a Student’s Own Words:

Question: Describe and discuss the classical school and its foundations and principles.

Some of the major tenets of the Classical School were punishment, due process, human rights, and rationality. Two people who had big impacts on the Classical School and had large inputs on it as well were Cesare Beccaria and Jeremy Bentham. Cesare came up with the idea that punishment was to deter people from committing crimes, he was huge on crime prevention, and believed that punishment for a crime should happened right after the crime is committed in order for it to have it’s effect and that their punishment should be equivalent to the crime they committed (stealing should be punished by paying a fine for example). Then there was Jeremy Bentham who believed that humans are fundamentally rational and that criminals will weigh in their minds the difference of pain and pleasure before committing the crime and the only way to prevent crime it for the punishment to outweigh the pleasure. The Classical School has definitely set so many precedents for our modern society and how criminology works today. For example it created due process of law so that each citizen has a right to a fair trial and is innocent till proven guilty and it put in place a code of ethics (that has most likely been revised) that our judicial system still uses. Without the classical school our judicial system and how criminology works today would be far behind compared to were we are now.

The Classical School has been a significant driving force in criminology and criminological theory. The legacy of the Classical School includes the following five principles.

People are rational. As humans have free will, the actions that take are a matter of choice.

People are motivated by pleasure and pain and reward and punishment as determinants of choice. People are hedonistic.

Punishment is a deterrent to unwanted and/or unlawful behavior and deterrence is the best justification for punishment.

Cooperation of people is what makes society possible. Therefore, society is obligated to respect the rights of citizens and their autonomy. Human rights are expected and individual rights are crucial, as long these rights do not endanger others or the common good.

Due Process. A person accused of a crime should be viewed as innocent until proven guilty. The person should not be punished until proven guilty.

Neoclassical School

Brandon Hamon

2.8 The Neoclassical School of Criminological Theory Copyright © 2024 by Brandon Hamann is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Classical ideology was the dominant paradigm for over a century, but it was eventually replaced by positivist approaches that seek to identify causes of criminal behavior. However, classical ideology had a resurgence during the 1970s in the United States. Neoclassical theory recognizes people experience punishments differently, and a person’s environment, psychology, and other conditions can contribute to crime as well (age, sex, race, etc.). Therefore, crime is a choice based on context. Many crime-prevention efforts used classical and neoclassical premises to focus on “what works” in preventing crime instead of focusing on why people commit criminal acts. While the Classical School saw punishment as a means to an end regarding criminal behavior, Neoclassical theory saw punishment more as a deterrent to future crime, using it to prevent more than to punish. Through the development of specific policies – which will be covered in a later section – Neoclassical theorists sought to change behavior through laws and sanctions (Fedorek, 2019).

Figure 2.10: Dr. Derek Cornish

Figure 2.10: Dr. Derek Cornish

Figure 2.11: Dr. Ronald Clarke

Figure 2.11: Dr. Ronald Clarke

Drs. Cornish and Clarke[1] (1986) proposed a theory of causation that took a risk/reward approach to criminal behavior. They claimed that offenders “rationally” calculated the costs and benefits of their actions, and if the rewards outweigh the risk, then a crime would most certainly be committed. They didn’t propose that all criminals were thinking rationally or that they were at all rational individuals outright – criminals aren’t having philosophical debates over the moral and ethical complexities of their actions – but if the situation presented itself, and the circumstances were right, then the probability of a criminal act were much higher.

Cohen and Felson[2](1979) claimed that changes in modern society and environment made it easier for crime to take place. Since the conclusion of World War II, more people had entered the workforce, and more people spent time away from home. This meant that more and more people became accustomed to the routine of their lives doing menial tasks in the view of the public eye (running errands, paying bills, making groceries, fueling the car, etc.). Cohen and Felson stated that three things must converge in time and space for a crime to be committed – a motivated offender, a suitable target, and the absence of a capable guardian. In theory, the activities of our routines make us more prone to being the victim of a criminal act.

Cornish and Clarke (1986) – proposed a theory of causation based on Rational Choice and risk/reward. ↵

Cohen and Felson (1979) – proposed a theory of causation based on the routine of people as changes in modern society forced them out of their private lives and into the public view. ↵

Rational choice theory is consistent with deterrence theory and deals more explicitly with the various factors that govern human decision-making. Specifically, it is the idea that people will think through a cost-benefit analysis (weighing the pros and cons) to determine whether a particular option is right for them. Legal consequences are only one of many considerations that individuals might think about as they decide whether or not to consider committing a crime. The potential benefits—or pleasures—of crime might outweigh any potential legal consequences, especially if the risk of getting caught is low.

Rational choice theory is, therefore, a broader framework than the notion of deterrence because it emphasizes the negative consequences (both formal and informal) of crime as well as the potential benefits. For example, if someone is very hungry and has no money to buy food, they may see a chance to steal from a market when no one is looking. They weigh the options of remaining hungry versus committing theft with only a small chance of getting caught. In this case, they rationally determine the benefits are worth the minimal risk for potential negative consequences.

Critiques of rational choice theory include an assumption that crime may be situational, as in some people may not really have a “choice” in their decision to commit a crime. Examples could include people who are under the influence of chemicals (drugs or alcohol for example), or people who are in a heightened state of emotions, angst or anger. While a rational choice theorist may argue people still make a decision to commit an act (and a crime), these are limitations to this theory and perspective. Other social factors such as poverty, environmental issues and poor socialization are also not considered in detail with rational choice theory.

Picture is sourced from pixabay.com

Picture sourced from Pixabay.com

In a Student’s Own Words:

Question: What do you think of the “rationality” aspect of crime and rational choice theory?

Rational choice theory, just as with all other theories, will have its weak spots and criticism. Kitteringham and Fennelly (2020) noted that one of the criticisms of this theory is the…”assumption that criminals are rational in their decision-making” (para. 1). However, as Mr. Bry noted in his video what if someone were under the influence of a substance, whether legal or illegal? These individuals may not have the same ability to make rational choices as someone whose thinking and decision making abilities have not been impacted.

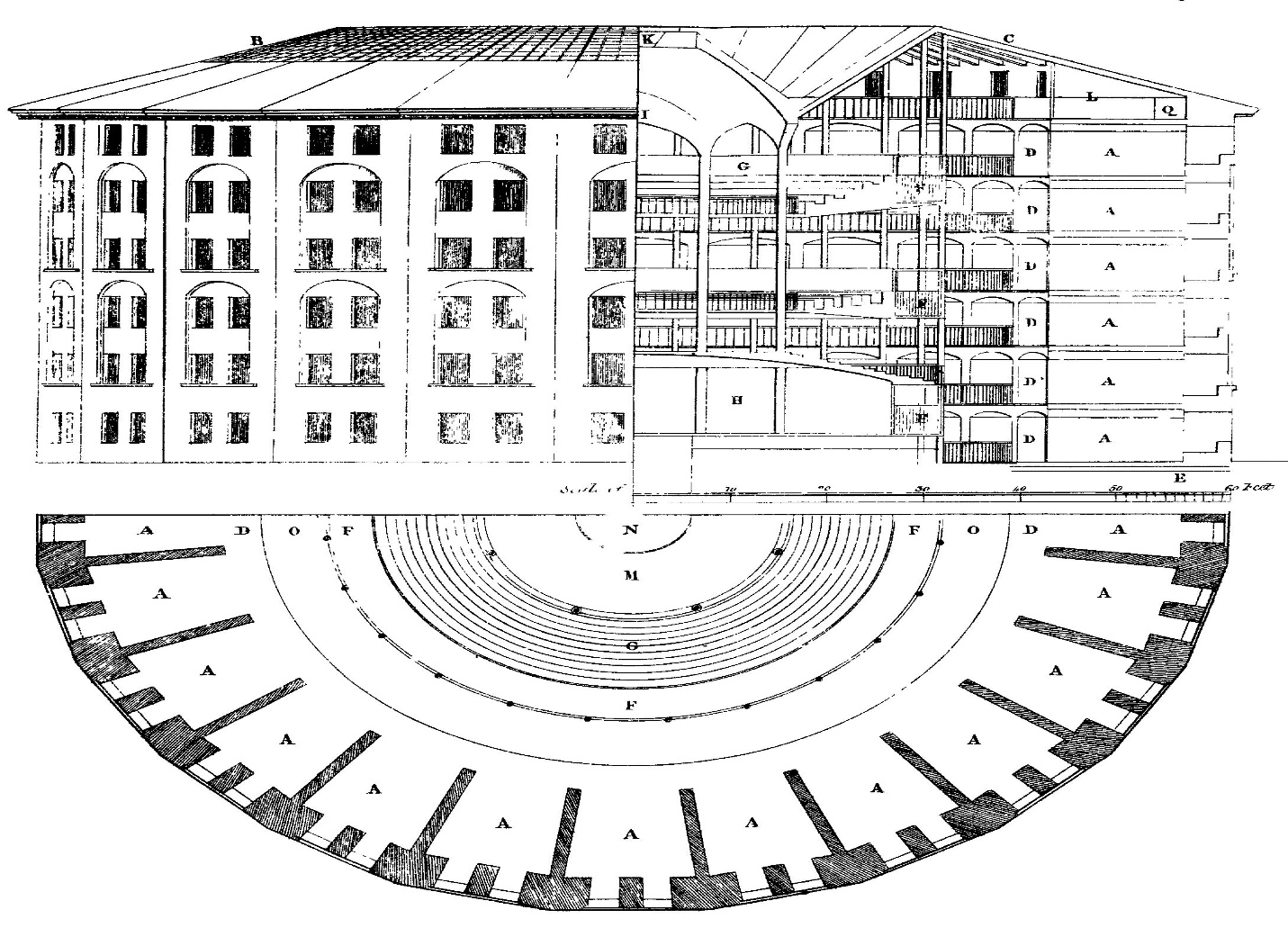

In addition to laying out this theory of human behavior, Bentham is well-known for a model of prison design referred to as the Panopticon (figure 3.3). The term “panopticon” literally translates to “all seeing” and is a bit of a mind trick devised by Bentham to keep people in order. Afterall, if the hungry person believes someone is watching them, they will not steal any food.

The Panopticon created by Bentham is a prison that is built on this very notion. It was designed so that a central tower was surrounded by a larger circle of cells. The central tower would house correctional authorities from where they see into every cell at all times and view residents of the prison constantly. The trick was that the people in the cells could not see into the tower, so they never actually knew whether they were being watched. They simply assumed they were being monitored at all times and behaved accordingly.

The Panopticon created by Bentham is a prison that is built on this very notion. It was designed so that a central tower was surrounded by a larger circle of cells. The central tower would house correctional authorities from where they see into every cell at all times and view residents of the prison constantly. The trick was that the people in the cells could not see into the tower, so they never actually knew whether they were being watched. They simply assumed they were being monitored at all times and behaved accordingly.

Bentham believed that this kind of design would lower the likelihood of misbehavior in prisons because residents would always feel under surveillance. This is consistent with his emphasis on rational choice. By raising the risk of apprehension, the design of the Panopticon could affect the decision-making of inmates.

Figure 3.3 Elevation, section and plan of Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon prison, executed by Reveley, 1791.

Although the philosophers who belong to the classical school of criminology made many assumptions about human nature and criminal behavior—for example, that humans had free will, were rational and hedonistic—their ideas preceded modern social scientific methods for testing these ideas. In addition, these texts were published as philosophical treatises focused on legal and social reform, and included no attempt at scientific explanation. Thus, the ideas in Beccaria’s and Bentham’s writings were not considered actual criminological theories until nearly 200 years later when researchers began testing them empirically.

Punishment and Neoclassical School

Punishment is a central element of classical and neoclassical perspectives. Punishment is valued for its deterrent effects in classical school, while neoclassical thought includes aspects of retribution and in some cases the utility of punishment as revenge.

From a neoclassical perspective, if someone makes a rational decision to violate the law they then deserve to be punished. This logic stems from the belief that the offender knowingly acted and committed the crime, even though they were well aware of the consequences for the crime prior to committing the act. While there are certainly criticisms to each of these perspectives, the neoclassical school tends to view punishment as being retribution or revenge for an offender’s actions. Keep in mind the punishment should fit the crime, so for minor offenses an apology or a minor punishment is sufficient. For more significant offenses, from a neoclassical perspective there should be more significant punishment.

The just desserts model takes the perspective of the sayings “an eye for an eye” or “he or she got what they deserved.” Just desserts takes the position offenders get when they deserve. The more severe and egregious the offense, the more severe the punishment. The just desserts model is cited back to the Old Testament of the bible, in terms of “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.” From this perspective punishment (even the death penalty, or life in prison) is what the offender deserves based upon the crimes they have committed. Certainly, the punishment must meet the offense, so less severe offenses receive a less stringent punishment.

The deterrence model is also a foundation of modern neoclassical perspectives. In modern times, deterrence has been separated into specific and general deterrence. Specific deterrence is deterrence designed to influence or affect an offender from conducting repeat crime. General deterrence is deterrence designed to influence or affect the general public from committing the same offense as a specific offender who is being punished. For deterrence to be effective, it is generally believed it needs to be swift, certain and severe to counteract the draw of committing crimes. As the criminal justice and court systems appear to be overwhelmed, this process is rarely as swift as advocates would hope. According to advocates of deterrence theory, this reduces the effectiveness of punishment.

Capital Punishment uses aspects of deterrence, just desserts and retribution to make its case for crime control. As the individual’s life is the most precious item they possess, the argument is the potential to lose this life will make them reconsider committing serious crimes. As the punishment needs to fit the crime, advocates of the death penalty generally argue the death penalty be reserved for the most serious offenses. Opponents to the death penalty make the argument that the death penalty is unfair and unjust, the poor and racial minorities are more likely to receive the death penalty. Opponents also argue the death penalty does not deter crime and that human life is sacred and should not be taken away by governmental entities.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU, 2012) https://www.aclu.org/documents/case-against-death-penalty takes the position the death penalty is not effective as a deterrent, also it is cost prohibitive. The ACLU cites the cost to put someone to death far exceeds the cost to pay for life in prison. The argument is also made that life in prison is a more severe sentence than the death penalty. The ACLU also argues too often innocent people are put to death. The ACLU points out that since 1973 to 2012, 156 people have been released from death row in 26 states as evidence was found to prove they were innocent.

Chapter Summary

This chapter examines the rule of law as well as classical and neoclassical viewpoints of crime control. As crime control is a constant issue debated and discussed in the United States, this chapter provides insight into the design of crime control policies and laws that are concerned with reducing or limiting offenses. While some of these approaches seem sensible and logical, other situational and social variables may play a hand in their effectiveness (mental health issues, addiction, environmental issues, etc).

References

3.1. Functions and Limitations of Law Copyright © 2019 by Lore Rutz-Burri is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

2.8 The Neoclassical School of Criminological Theory Copyright © 2024 by Brandon Hamann is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

The American Civil Liberties Union. https://www.aclu.org/documents/case-against-death-penalty

Beccaria, C. (1764). On Crimes and Punishments. Translated by Henry Paolucci. Hackett Publishing Company, 1986.

Bentham, J. (1789). An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. Clarendon Press.