7 Republic of Ireland

Cheryl Van Den Handel

Cheryl Van Den Handel teaches Comparative Politics, International Relations, and Women’s Studies at Northeastern State University in the heart of Cherokee Nation, Tahlequah, Oklahoma. She holds five degrees in Political Science, including bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi, a Master of International Studies and Ph.D. in Comparative and World Politics at Claremont Graduate University. Her current areas of interest are impediments to women participating in politics and how to overcome them, open educational resources, and immersive learning.

Chapter Outline

Section 2: Ethnic, Religious, and Cultural Identity

Section 3: Political Culture and Civil Society

Section 4: Political Participation

Section 5: Formal Political Institutions

Section 8: Irish Political Data

Why Study this Case?

The Republic of Ireland is a medium-income country within the European Union, and not typically studied in many comparative politics courses. While it is not geopolitical player, it’s political history is a fascinating study in the confluence of the Catholic Church’s influence on society with its domestic politics. Ireland is the only other state in Europe besides Italy, where the Catholic Church still has a strong hold on society. From the early 19th century to the early 20th century, Ireland was part of the United Kingdom, achieving Dominion status in 1922 and independence in 1948. Ireland and its people experience substantial relations with the United States as well as strong economic ties to the European Union. Its fraught history of civil wars and its relationship with the Church make it an important comparative study in nation-building among a divided people.

Section 1: Brief History

From the Act of Union on January 1, 1801 until December 6, 1922, the island of Ireland was part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. During the Great Famine, which lasted from 1845 to 1849, the island’s population, exceeding eight million, decreased by 30%. Approximately one million Irish people died from starvation and disease, while another 1.5 million emigrated, predominantly to the United States. This emigration pattern continued throughout the following century, leading to a steady population decline until the 1960s.

The Irish Free State was established with Dominion status in 1922, following the Anglo-Irish Treaty. In 1937, a new constitution was adopted, renaming the state “Eire” or “Ireland” in English. This effectively transformed it into a republic, featuring an elected non-executive president.

Although the Third Home Rule Act received Royal Assent and was placed on the statute books in 1914, its implementation was postponed until after the First World War, thereby defusing the threat of civil war in Ireland. In hopes of securing the Act’s implementation following the war through Ireland’s participation, John Redmond and the Irish National Volunteers supported the UK and its Allies. Consequently, 175,000 men joined Irish regiments of the 10th (Irish) and 16th (Irish) divisions of the New British Army, while Unionists joined the 36th (Ulster) division (Encyclopedia Britannica, 2024).

However, a faction of the Irish Volunteers, who opposed any support for the UK, initiated an armed insurrection against British rule during the 1916 Easter Rising alongside the Irish Citizen Army. This uprising began on April 24, 1916, with the declaration of independence. After a week of intense fighting, primarily in Dublin, the surviving rebels were compelled to surrender. The majority were imprisoned, and fifteen of the prisoners, including most of the leaders, were executed for treason. These events, together with the Conscription Crisis of 1918, profoundly shifted public opinion in Ireland against the British Government (Encyclopedia Britannica, 2024).

In January 1919, following the December 1918 general election, seventy-three of Ireland’s 105 Members of Parliament (MPs) elected were Sinn Féin members, who had run on a platform of abstentionism from the British House of Commons. These members convened an Irish parliament called Dáil Éireann. The first Dáil issued a declaration of independence and proclaimed the Irish Republic, largely reiterating the 1916 Proclamation with the added provision that Ireland was no longer part of the United Kingdom.

After the War of Independence and the truce in July 1921, representatives of the British government and five Irish treaty delegates, including Arthur Griffith, Robert Barton, and Michael Collins, negotiated the Anglo-Irish Treaty in London from October 11th to December 6, 1921. The Irish delegates privately decided on December 5th to recommend the treaty to Dáil Éireann. On 7 January 1922, the Second Dáil ratified the Treaty by sixty-four votes to 57.

In accordance with the Treaty, on December 6, 1922, the entire island of Ireland became self-governing, called the Irish Free State (Saorstát Éireann). Under the new constitution, the Parliament of Northern Ireland could leave the Irish Free State and rejoin the United Kingdom one month later. During this interim period, the powers of the Parliament and the Executive Council did not extend to Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland exercised its treaty right and rejoined the United Kingdom on December 8, 1922.

The signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty led to the Irish Republican Army splitting into two factions. One side supported the treaty, and the other believed that it required an oath to the King of England. Civil war broke out between the factions. The English government supplied the pro-treaty forces with the assistance of the Black and Tans, and with the support of WWI veterans, they overcame the anti-treaty faction. See The Signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, 1921 (Malone).

Officially, Ireland was declared a republic in 1949, following the enactment of the Republic of Ireland Act of 1948. Ireland became a member of the United Nations in 1955 and joined the European Communities (EC), the predecessor to the European Union (EU), in 1973.

For most of the 20th century, Ireland had no formal relations with Northern Ireland. However, during the 1980s and 1990s, the British and Irish governments, alongside Northern Irish parties, engaged in efforts to resolve the conflict known as the Troubles. Since the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, the Irish government and the Northern Irish government have collaborated on various policy areas through the North/South Ministerial Council established by the Agreement (Contributors, 2024).

Ireland and the United States celebrated their 100-year relationship in October 2024. On October 7, 1924, Professor Timothy Smiddy presented his credentials to President Calvin Coolidge. The U.S. was the first country to formally recognize Ireland’s independence. Today, over thirty million Americans, roughly 6% of the population, claim Irish descent. The strength of the relationship exists through common ancestral bonds, shared values, and strong economic ties. The majority of multinational corporations producing in Ireland are based in the United States (Ireland.ie, 2024).

Section 2: Ethnic, Religious, and Cultural Identity

Population

total: 5,233,461

male: 2,590,542

female: 2,642,919 (2024 est.)

Nationality

noun: Irishman(men), Irishwoman(women), Irish (collective plural)

adjective: Irish

Ethnic groups

Irish 76.6%, Irish travelers 0.6%, other White 9.9%, Asian 3.3%, Black 1.5%, other (includes Arab, Roma, and persons of mixed backgrounds) 2%, unspecified 2.6% (2022 est.)

Celtic tribes arrived in Ireland between 600 and 150 B.C. Norse invasions that began in the late eighth century finally ended when King Brian BORU defeated the Danes in 1014. Norman invasions began in the 12th century and set off more than seven centuries of Anglo-Irish struggle marked by fierce rebellions and harsh repressions. The Irish famine of the mid-19th century caused an almost 25-percent decline in the island’s population through starvation, disease, and emigration. The population of the island continued to fall until the 1960s, but over the last 50 years, Ireland’s high birthrate has made it demographically one of the youngest populations in the EU.

Languages

English (The official language), Irish (Gaelic or Gaeilge) (official, spoken by approximately 37.7% of the population as of 2022; spoken in areas along Ireland’s western coast known as gaeltachtai, which are officially recognized regions where Irish is the predominant language)

Religions

Roman Catholic 69.2% (includes lapsed), Protestant 3.7% (Church of Ireland/England/Anglican/Episcopalian 2.5%, other Protestant 1.2%), Orthodox 2%, other Christian 0.9%, Muslim 1.6%, other 1.4%, agnostic/atheist 0.1%, none 14.5%, unspecified 6.7% (2022 est.)

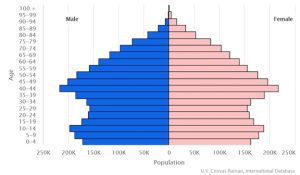

Age structure

0-14 years: 18.6% (male 498,124/female 477,848)

15-64 years: 65.5% (male 1,701,680/female 1,728,041)

65 years and over: 15.8% (2024 est.) (male 390,738/female 437,030)

Section 3: Political Culture and Civil Society

3.1 – Colonialism and Activism

As a result of colonialism, Irish political culture is defined by its institutionalized nature and civil society control maintained by the Catholic Church. Rather than inculcating a strong notion of citizenship in the Irish state within primary and secondary education, schooling is primarily controlled by the Church, causing the formation of a “religious-ethnic conceptualization of the state (Murphy, 2011).” As a result, the Church maintained authoritarian social controls at the parish level, “promoting deference, victimhood, and internalization of blame and anger (Murphy, 2011).” This social control has had the effect of limiting the development and growth of progressivism. For a full explanation of Irish Civil Society, read the article Civil Society in the Shadow of the Irish State by Mary P. Murphy.

In the early 20th century, Ireland experienced uprisings from the socialist labor and trade union movement. Despite those occurrences, the political left in Ireland has been fragmented and marginalized. The presence of the Church in politics, the conservative electoral environment, the lack of industrialization, the weakness of the Labor Party and Fianna Fail, and a social focus on individualism over collectivism have all been inhibiting factors.

However, in the 1970s and 1980s, Ireland was rife with progressive activism, one of the largest being the women’s movement. Other active movements in that era included environmentalism, anti-capitalism, gender and sexual orientation activism, equality and antipoverty activism, and trade unionism. Overall, Ireland’s level of civil society activism in the 2020s is on par with that of the mainstream European Union.

The Taskforce on Active Citizenship (2007) shows that Ireland’s civil society participates in about 24,000 organizations, and only 18.25% participate in political activism. Ireland also has one of the lowest membership rates in political parties and voting participation in the European Union. The Taskforce found that 38% report being either ‘definitely or somewhat’ interested in politics, 54% thought they can influence local decision-making, and 76% of adults ages 20-29 are registered to vote. Yet many feel that local governments and developers do not listen to citizens’ concerns and needs and refer to the population as “customers” rather than “citizens.” Thus, the population expresses cynicism about democracy and consultative services (Government of Ireland, 2016).

3.2 – Abortion and the Repeal of the Eighth Amendment

Access to abortion in Ireland has long been illegal, with minor exceptions. Initially, the British Offenses Against the Persons Act in 1861 made it illegal to “seek a miscarriage.” That remained in place until Independence in 1922. The Eight Amendment to the Constitution was adopted in 1983, stating that “the right to life of the unborn … equal [to the] right to life of the mother.” It stood until the Supreme Court ruled in 1992 that an abortion is allowed when a pregnancy threatens a woman’s life, including suicide. Yet legislation was not passed until the Protection of Life During Pregnancy Act of 2013, repealing the 1861 Act. The UK’s 1967 Abortion Act permitted Irish women to come to the UK for abortions. Irish women seeking an abortion were at a high in 2001 with 6673 but declined to 3265 in 2016. The decline was due to the increase in the illegal use of abortion drugs.

Civic action over the abortion issue increased over the first decade-plus of the 21st Century. The Abortion Rights Campaign was formed in 2012, holding an annual March for Choice, which was countered by the “Rally for Life.” As the 2016 election campaign gained momentum, many political parties committed to a referendum to repeal the Eighth Amendment. These included Labor, the Green Party, the Social Democrats, Sinn Fein, and the Workers Party. Fianna Fail and Fine Gael were opposed. The Fine Gael party government, elected in 2016 led by Taoiseach Enda Kenny agreed to a Citizens Assembly to study the abortion issue. Leo Varadkar succeeded Kenny, promising to hold a referendum in 2018. Citizen groups lined the downtown main street in Dublin, passing out flyers and stopping passersby to support their position on the issue (Van Den Handel, 2018). A heightened sense of history permeated the Dublin population and the countryside. Social media was a significant tool for organizing the pro-choice position.

The Citizens Assembly issued its report in April 2017, which then went to a special Oireachtas committee. The committee voted to support repealing the Eighth Amendment and permitting the Oireachtas to legislate on abortion. The Oireachtas committee recommended that abortion be legal up to the first 12 weeks, given the difficulty of legislation for rape and incest, and did not recommend abortion due to a mother’s economic condition. A Supreme Court ruling on March 7, 2018, set aside an earlier lower court ruling, stating that a fetus is not a child and had no rights. This opened the door for the Department of Health to publish a paper, “Regulation of Termination of Pregnancy” on March 9th. That paper comprised the body of the legislation. It passed the Dial on March 21st and the Seanad on March 27th. Fine Gail and Fianna Fail permitted their MPs to vote their conscience. They voted overwhelmingly for YES. These two major parties supported the YES campaign. While most abortions were still illegal, the Eighth Amendment was repealed and abortions before the 12th week became legal. A public referendum was scheduled for May 25th.

An American anti-abortion group arrived to assist with the NO movement in early May. This caused controversy because it was promulgated that they had lied to border control about their reasons for coming to Ireland. Irish expatriates began arriving across May to vote in the referendum. Any Irish citizen abroad for no more than 18 months were permitted to vote. For lists of YES and NO organizations, religious groups, and votes in the Oireachtas, see “The Thirty-sixth Amendment to the Constitution (Wikipedia Contributors, 2024).” YES, won 66.4% of the vote to 33.6% of the NO, adding the Thirty-Sixth Amendment to the Constitution. This was a resounding defeat to the Catholic Church, which issued a statement that anyone who had voted yes must come to confession.

Section 4: Political Participation

Read the following research article by Donal O’Brolchain , Direct Political Participation in the Republic of Ireland ‐ 20 November 2013 (O’Brolchain, 2013), about broadening democracy by instituting direct democracy to a greater degree. Direct democracy was written into the 1921 Constitution but never implemented. The Oireachtas is permitted to change the Constitution without a public referendum.

Section 5: Formal Political Institutions

(Central Intelligence Agency, 2024)

5.1 – Executive Branch

Chief of State: President Michael D. HIGGINS (since 11 November 2011)

Head of government: Taoiseach (Prime Minister) Simon HARRIS (since 9 April 2024)

Cabinet: Cabinet nominated by the prime minister, appointed by the president, and approved by the Dail Eireann (The House of Representatives, the lower house of Parliament).

Ireland operates as a constitutional republic with a parliamentary system of governance. The Oireachtas is the bicameral national parliament and comprises the President of Ireland and the two Houses: Dáil Éireann (House of Representatives) and Seanad Éireann (Senate). The President’s official residence is Áras an Uachtaráin, while the sessions of the Oireachtas are held at Leinster House in Dublin.

The President, who functions as the head of state, is elected for a seven-year term and may be re-elected once. Although the role is primarily ceremonial, the President possesses certain constitutional powers, exercised with the counsel of the Council of State, and holds absolute discretion in specific areas, such as referring a bill to the Supreme Court to assess its constitutionality. Michael D. Higgins assumed office as the ninth President of Ireland on November 11, 2011.

The Taoiseach (Prime Minister) is the head of government, appointed by the President following nomination by the Dáil. Typically, the Taoiseach is the leader of the political party that secures the majority of seats in national elections. Coalition governments have become the norm since 1989, as no single party has achieved an outright majority.

The Dáil consists of 160 members (Teachtaí Dála) elected from multi-seat constituencies through proportional representation using the single transferable vote system. The Seanad comprises sixty members: eleven nominated by the Taoiseach, six elected by two university constituencies, and forty-three elected by public representatives from vocational panels.

Constitutionally, the government is restricted to fifteen members, with no more than two drawn from the Seanad. The Taoiseach, Tánaiste (Deputy Prime Minister), and Minister for Finance must be Dáil members. The Dáil must be dissolved within five years of its initial meeting following an election, with general elections held within thirty days of dissolution. According to the Constitution, parliamentary elections must occur at least every seven years, though statutory law may impose a shorter interval. The current government is a coalition of Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael, and the Green Party, with Simon Harris of Fine Gael as Taoiseach and Micheál Martin of Fianna Fáil as Tánaiste. The opposition includes Sinn Féin, the Labor Party, People Before Profit–Solidarity, Social Democrats, Aontú, and several independents.

Elections/appointments: The president is directly elected by majority popular vote for a 7-year term and is eligible for a second term. The last election was held on October 26, 2018 (next to be held no later than November 2025). The Taoiseach (prime minister) is nominated by the Dail Eireann (House of Representatives) and appointed by the president.

Election results:

2024: Simon HARRIS was elected Taoiseach by the parliament, 88 votes to 69, and was appointed Taoiseach by the president.

2018: Michael D. HIGGINS, an Independent, was reelected president in first round of voting with 55.8% of the vote;

2011: Michael D. HIGGINS (Labor Party) was elected president in second round with 39.6% of the vote.

5.2 – Legislative branch

The Oireachtas is the bicameral Parliament, which consists of the Senate or Seanad Eireann, which has 60 seats, 49 of which are indirectly elected from 5 vocational panels of nominees by an electoral college and 11 appointed by the prime minister. The House of Representatives or Dail Eireann has 160 seats, with members directly elected in multi-seat constituencies by proportional representation vote. All Parliament members serve 5-year terms.

Seanad Eireann elections were last held early on May 21-30, 2020 (next to be held in March 2025). The number of men is 36, and the number of women is 24; and the percentage of women was 40%.

Dail Eireann Representatives elections were last held on 8 February 2020 (next to be held no later than March 2025). The number of men is 123, and the number of women is 37. The percentage of women is 23.1%. The total percentage of women in the Oireachtas is 27.7%. (https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/legislative-branch/)

|

Seats in the Oireachtas 2020 Elections |

||

| Seanad Eireann | ||

| Party | Percentage | Seats |

| Fianna Fail | 35 | 21 |

| Fine Gail | 26.7 | 16 |

| Green | 6.7 | 4 |

| Labor | 6.7 | 4 |

| Sinn Fein | 4 | 4 |

| Independent | 16.6 | 10 |

| Other | 1 | 1 |

| Total Seats | 60 | |

| Dail Eireann | ||

| Party | Percentage | Seats |

| Fianna Fail | 23.8 | 38 |

| Fine Gail | 21.9 | 35 |

| Green | 7.5 | 12 |

| Labor | 3 | 6 |

| Sinn Fein | 23.1 | 37 |

| Social Democrats | 3 | 6 |

| PBPS | 3 | 5 |

| Independent | 11.9 | 19 |

| Other | 1 | 2 |

| Total Seats | 160 |

5.3 – Judicial branch

Ireland’s courts include the Highest court, the Supreme Court of Ireland consisting of the chief justice, 9 judges, and 2 ex-officio members. The presidents of the High Court and Court of Appeal are organized in 3-, 5-, or 7-judge panels, depending on the importance or complexity of an issue of law. The Taoiseach and Cabinet nominate judges, who are then appointed by the President. The chief justice serves in the position for 7 years and judges can serve until age 70. Subordinate courts include the High Court, the Court of Appeal, circuit and district courts, and criminal courts. (https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/judicial-branch)

5.4 – Political Parties

Ireland hosts a variety of political parties, and coalition governments are a common feature of its political landscape. The two historically dominant parties, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, originated from a split within the original Sinn Féin. Fine Gael is the successor of Cumann na nGaedheal, the faction that supported the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty, while Fianna Fáil was established by members of the anti-Treaty faction who opposed Sinn Féin’s abstentionism. This division over the Treaty also led to the Irish Civil War (1922–23), and the enduring distinction between the parties has been characterized as “Civil War politics,” contrasting with a more typical left-right political spectrum. Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael are sometimes derogatorily referred to collectively as “FFG.”

As of 2023, Fianna Fáil and Sinn Féin share the highest representation in Dáil Éireann, with Fine Gael following closely in third place. The Green Party overtook the Labor Party in 2020. The Labor Party, founded in 1912, had traditionally been the third-largest party but currently ranks fifth in the Dáil, closely followed by the Social Democrats.

The Electoral Commission, established under the Electoral Reform Act 2022, maintains the Register of Political Parties. Prior to the Commission’s formation in 2023, the Houses of the Oireachtas managed this register. To register for national elections, a party must have at least one member in Dáil Éireann or the European Parliament or 300 recorded members aged 18 or over. Parties registering solely for elections in a specific part of the state or for local elections need only 100 recorded members aged 18 or over. In either case, at least half of the recorded members must be on the register of electors.

Section 6: Political Economy

The Republic of Ireland has a mixed economy, meaning private initiatives are preferred to operate in the free market. Still, the government heavily regulates the market, intervening to ensure the best benefit for the state.

In the post-Cold War period, Ireland’s economy grew rapidly from the 1990s to 2007 due to investment by U.S. technology companies. With high growth came high inflation, and the housing market became overpriced in Dublin compared to the rest of the country. Heavy investment by technology companies means Ireland’s GDP (gross domestic product) is skewed in that direction, masking the country’s gross national income. At the same time, Ireland became one of the wealthiest countries in the OECD, ranking 4th in gross national income. GNI is a better measure of Ireland’s economy than its GDP, as it excludes the results of U.S. tech investment. The Economist found that Ireland ranks as having one of the best quality of life ratings in the OECD.

The imbalance between the technology sector and other sectors of the economy led to a downturn in housing purchases due to inflation, causing residential property construction to drop and unemployment to begin rising due to the recessionary ripple effect. Upwards of 6.8% of the population was living below the poverty line, and more were at risk of becoming impoverished.

In 2008, Ireland’s economy tanked. It suffered through a bank crisis followed by a housing crisis, which mirrored the United States’s recessionary spiral. Ireland had an over-supply of housing stock and too few buyers. Yet, the banks financed Irish land speculators, adding up to some 28% of bank lending, three percent larger than Japan’s construction lending before its 1989 bank crash. This equaled the total of all public deposits at the time. If loans had been called in, Ireland would not have been able to pay its debts. (Wikipedia Contributors 2024: CCbyNC, SA, revised, remixed, and reused by Cheryl Van Den Handel)

The Irish government instituted the National Recovery Plan in November 2010 to bring its debts down and its deficits aligned with the European Union’s 3% ceiling. An overall reorganization of the tax structure, increasing taxes, and reducing government spending brought the budget deficit from 35.2% of GDP in 2010 to 5.7% of GDP in 2013. Government debt had risen to 120% of GDP in 2013, but by 2023, the debt load had decreased to 42.8%. Beginning in 2014, housing stock in Dublin started to increase in price as demand exceeded supply. That year, Ireland’s economic growth rate was 4.2%, better than the rest of the E.U (Ihle, 2008).

Corporate tax rates were reduced to almost zero to encourage investment during the crisis, leading to 80% of the economic recovery due to multinational technology companies’ growth. This prompted U.S. investors to use Ireland as a tax haven. The Obama Administration countered the tax-inversion scheme to prohibit U.S. companies from hiding their income in Ireland from U.S. taxes (Carswell, 2016). Other countries followed suit. Ireland’s recovery from the crisis proceeded in a positive direction from 2014 to 2023 and is projected to continue steadily.

Exports are a large part of Ireland’s economy after the tech sector. It is one of the world’s largest exporters of pharmaceuticals, medical equipment, and related software. Because pharmaceuticals are multinational companies, any slight upturn or downturn in exports distorts GDP (McCall, 2024). Significant discoveries of some base metals, such as zinc-lead ores, have led Ireland to become the seventh-largest exporter of zinc in the world and the twelfth-largest exporter of lead concentrates. It is the largest producer of zinc in Europe and the second largest producer of lead concentrates (Irish National Resources, 2008).

Section 7: Foreign Relations

In the comparative view of foreign affairs, foreign policies can be studied within a country over time, at a specific time in history, or comparatively between countries. Unlike international relations, the purpose is not to study the relationship between countries, but to compare policies and actions through most similar systems or most different systems of analysis (Government of Ireland).

Ireland’s foreign affairs are conducted through the Office of the Taoiseach. It has been a member of the European Union for 50 years, joining the European Economic Community (ECC) in 1973. The Irish mission to the EU is in Brussels and encourages representatives from across the social, political, and economic spectrum to participate. Ireland’s foreign policies are the same as those in the European Union. For example, Ireland does not levy sanctions on other countries but joins E.U. and U.N. sanctions regimes. Penalties for breaches of sanctions are statutory. The Department of Foreign Affairs is responsible for maintaining communications with the E.U. and the U.N., representing Ireland in numerous committees and working groups. The department also communicates regularly with individuals who are on the restricted list. Those individuals can appeal their restricted status to the Council of the E.U. Within the E.U. sanctions regimes, states must have a set of three competent authorities. Ireland’s three authorities handling areas of the sanctions regimes are The Department of Foreign Affairs, The Department of Enterprise, Trade, and Employment, and the Central Bank of Ireland (Government of Ireland, 2004).

The Joint Committee on European Union Affairs conducts the Oireachtas’ oversight function in this regard. It considers EU-related bills and motions, conducts various council meetings, invites witnesses and experts on important issues, and oversees cross-sectional policy matters, among other oversights. The committee regularly updates the Oireachtas, as EU matters are a permanent action item on the houses’ agendas (Government of Ireland, 2004).

Section 8:Irish Political Data

This website contains a wide range of data on Irish politics (Muller, Republic of Ireland). It includes national election studies, public opinion, party politics, and legislative texts. “The Irish Politics Data project collects links to datasets, text corpora, and dashboards on Irish politics. The website features polling results, national and cross-national surveys, election results, legislative data, party manifestos, parliamentary speeches, policy agendas, annual reports, and relevant literature from both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. The project aims to guide researchers, policymakers, journalists, and citizens to data and empirical literature on politics on the island of Ireland. Created by Stefan Müller, contributions of data or literature are welcomed (Muller, Stefan Muller).”

References

Carswell, S. (2016, April 5). Obama calls inversions ‘one of the most insidious tax loopholes’. The Irish Times.

Central Intelligence Agency. (2024). CIA WorldFactBook. Retrieved from Ireland: cia.gov/the-worldfactbook/countries/Ireland

Contributors, W. (2024). History of Ireland. Retrieved from Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=History_of_the_Republic_of_Ireland&oldid=1264142812 (CCbyNC, SA, revised, remixed, and reused by Cheryl Van Den Handel)

Encyclopedia Britannica. (2024, December). Irish War of Independence. Retrieved from Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/event/Irish-War-of-Independence

Government of Ireland. (2004). Guidelines for Departments in relations to the Scrutiny of EU Matters by the Houses of the Oireachtas. Retrieved from Ireland.ie: https://www.ireland.ie/en/eu/guidelines-scrutiny-of-eu-matters-by-oireachtas/

Government of Ireland. (2004). Restrictive Measures. Retrieved from Ireland.ie: https://www.ireland.ie/en/eu/restrictive-measures-sanctions/

Government of Ireland. (2016). Report of the Taskforce on Active Citizenship. Retrieved from https://hubnanog.ie/report-of-the-taskforce-on-active-citizenship/

Government of Ireland. (n.d.). Ireland at the European Union. Retrieved from Ireland.ie: https://www.ireland.ie/en/eu/

Ihle, J. (2008, October 12). NIB Figures Hint at Depth of Bad Debt Problems. Tribune Business, 25(41). Retrieved from Tribune Business (Internet Archive Wayback Machine): https://web.archive.org/web/20081019105728/http:/www.tribune.ie/business/article/2008/oct/12/nib-figures-hint-at-depth-of-bad-debt-problems/

Ireland.ie. (2024). 100 Years of Diplomatic Relations Between Ireland and the United States. Retrieved from Ireland in the USA: https://www.ireland.ie/en/usa/centenary/

Irish National Resources. (2008, July 15). Operational Irish Mines: Tara, Gilmoy, and Lisheen. Retrieved from https://irishresources.wordpress.com/2008/07/15/irish-mines-now-operating-tara-galmoy-and-lisheen/

Malone, B. (n.d.). The Signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. Retrieved from National Museum of Ireland and the Dept. of Tourism, Culture and Arts, Sports, and Media: https://www.museum.ie/en-IE/Collections-Research/Collection/Documentation-Discoveries/Artefact/The-Signing-of-the-Anglo-Irish-Treaty,-1921/7a49e7e5-7cf7-4218-b3b4-c974d4adafa6

McCall, B. (2024, December 19). Irish Economy ‘motoring on’ despite geopolitical turbulence. The Irish Times. Retrieved from https://www.irishtimes.com/special-reports/2024/12/19/irish-economy-motoring-on-despite-geopolitical-turbulence/

Muller, S. (n.d.). Republic of Ireland. Retrieved from Irish Politics Data: https://irishpoliticsdata.com/republic-of-ireland/

Muller, S. (n.d.). Stefan Muller. Retrieved from https://muellerstefan.net/

Murphy, M. P. (2011). Civil Society in the Shadow of the Irish State. Irish Journal of Sociology, 19(2). Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/data-tools/demo/idb/#/dashboard?dashboard_page=country&COUNTRY_YR_ANIM=2025&CCODE_SINGLE=IE&subnat_map_admin=ADM1&CCODE=IE

O’Brolchain, D. (2013). Direct Political Participation in the Republic of Ireland: Citizen-initiated referendums on the horizon? Retrieved from Democracy International: https://www.democracy-international.org/sites/default/files/PDF/Publications/2013-11-25_direct_political_participation_in_the_rofireland.pdf

U.S. Census Bureau. (2024). International Database. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/data-tools/demo/idb/#/dashboard?dashboard_page=country&COUNTRY_YR_ANIM=2025&CCODE_SINGLE=IE&subnat_map_admin=ADM1&CCODE=IE

Van Den Handel, C. (2018, May ). Direct observation of political activity on O’Connoll Street. Dublin, Ireland.

Wikipedia Contributors. (2024). Economy of the Republic of Ireland. Retrieved from Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economy_of_the_Republic_of_Ireland (CCbyNC, SA, revised, remixed, and reused by Cheryl Van Den Handel)

Wikipedia Contributors. (2024). Thiry-sixth Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland. Retrieved from Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Thirty-sixth_Amendment_of_the_Constitution_of_Ireland&oldid=1264651595 (CCbyNC, SA, revised, remixed, and reused by Cheryl Van Den Handel)