8 Nigeria

Matthew Schuster

Matthew Schuster teaches political science at Anoka-Ramsey Community College and Metropolitan State University in Minnesota. He holds a bachelor’s degree in philosophy and political science from the University of Minnesota, master’s degrees in political science and history from Arizona State University and American Public University and is currently working on an EdD in adult education. His primary areas of interest are political science education, political theory, and issues related to equity.

Funding support for the writing of this chapter was provided through a Minnesota State Colleges and Universities (MinnState) Learning Circle.

Chapter Outline

Section 1: Geography and History

Section 2: Ethnic, Religious, and Cultural Identity

Section 3: Political Culture and Civil Society

Section 4: Political Participation

Why Study this Case?

Nigeria is not a wealthy country, like the United States. It is not a country willing to use its military and/or economic power to exert its will on others in the way Russia does. Nigeria has not been historically influential, like Great Britain. Even if we compare Nigeria to its African, or even west African counterparts, Nigeria is not the wealthiest country, the most powerful country, or the most democratic country. But Nigeria is, in many ways, a typical African country that is both interesting and important. It is interesting and important because of its size and rate of growth, resources and poverty, history and potential future, and its diverse people and culture. As a continent, Africa is home to 54 distinct and diverse nations. West Africa, as defined by the United Nations, is home to 16 distinct and diverse nations. Nigeria is home to hundreds of different cultures and a quarter of a billion distinct and diverse people. Nigeria is important to study because of both the similarities and differences it shares with other nations in West Africa, Africa, and around the world.

Section 1: Geography and History

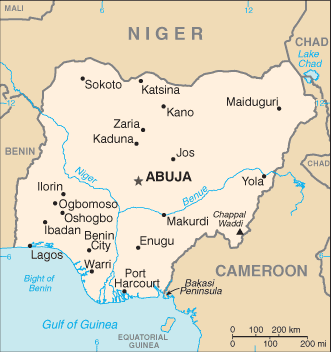

Nigeria is in west Africa along the Gulf of Guinea. It borders Benin to the west, Niger to the north, Chad along its northeast corner, and Cameroon along its eastern border. The capital city, Abuja, is located near the center of Nigeria. Lagos, in the southwestern corner, is Nigeria’s largest city. It has two major rivers that enter along its western border and eastern border, converge in the south-central part of the country, and exit at a delta in the Gulf of Guinea. Nigeria is rich in natural gas, petroleum, tin, iron ore, coal, limestone, niobium, lead, zinc, and arable land.

The Nigeria we know today started taking shape in the mid to late 1800s. Yet, the history of the people and cultures that currently live in modern-day Nigeria began long before that. One of the earliest known civilizations in what is now Nigeria was the Nok civilization starting around 1500 B.C.E. The Nok had developed metallurgy by around 200 B.C.E. but are perhaps most known for their large terracotta statutes that date to the early days of their civilization. The Hausa have a recorded history in northern Nigeria dating to about the 9th century C.E. and the Igbo consolidated during the 10th century.

Nok Terracotta Sculpture (https://worldhistorycommons.org/nok-terracotta-sculptures)

In the 7th and 8th centuries, Islam spread through the Saraha region of Africa. By the 11th century, Muslim traders were establishing trade routes in the northern part of modern-day Nigeria. Today, Islam is the dominant religion in the northern part of the country.

In the 1500s, the Portuguese were the first Europeans to enter and trade with Nigeria. It was also during this time that the first Nigerians were enslaved as part of the Atlantic slave trade. While slavery was not new to the people of the region, it should be noted that the slavery that existed prior to European enslavement was not race-based nor intergenerational. It was usually based on conquest or was used to punish prisoners. In most cases, too, it was not permanent.

From the 1500s to the 1800s, various groups tried to control different parts of what is now Nigeria. These included both European and African groups. From the mid-1800s until 1903, Great Britain worked to gain sole political control over Nigeria. In 1884, Great Britain officially colonized Nigeria at the Berlin Conference. Great Britain was, eventually, able to garner control by establishing a federal system that granted limited autonomy within various regions.

After World War II, the European countries began to give up their colonial control over most of the countries they had colonized in Africa and Asia. Nigeria gained political independence from Great Britain and the First Republic was established in October of 1960. Between 1960 and 1999, Nigeria experienced civil wars, military coups, and rise and fall of three republican governments. In 1999, the fourth and current republic was established and has been maintained to this day. It has even seen the peaceful transition of power from one party to another in 2015.

|

1500s B.C.E. |

Nok empire forms. |

|

1100s B.C.E. |

The Hausa kingdom forms in the north; Oyo kingdom forms in the southwest. |

|

1000s |

Muslims traders establish trade routes in the north. |

|

1472 |

Portuguese arrived in the south. |

|

1861-1914 |

Britain establishes control. |

|

1960 |

Nigerian independence and the First Republic. |

|

1967-1970 |

Civil War. |

|

1976 |

Olusegun Obasanjo comes to power and begins transition to civil rule. |

|

1979 |

The Second Republic is established. |

|

1983-1993 |

Military rule regains power. |

|

1993 |

Transition to civilian rule; Third Republic fails; Sani Abaca seizes power. |

|

1995 |

Ken Saro-Wiwa is executed. |

|

1998 |

Abacha dies and is succeeded by Abdulsalami Abubakar. |

|

1999 |

Fourth Republic established; Obasanjo is elected president. |

|

2007 |

Obasanjo steps down; Umaru Yar’Adua comes to power through a fraudulent election. |

|

2009 |

Boko Haram begins insurgency in the north. |

|

2010 |

Vice President Goodluck Jonathan becomes president after Yar’Adua dies. |

|

2014 |

Boko Haram kidnaps 200 schoolgirls. |

|

2014-2016 |

The Nigerian government works with neighboring nations to greatly decrease Boko Haram’s power and influence. |

|

2015 |

Muhammadu Buhari is elected president in a peaceful transition from one party to another. |

|

2023 |

Bola Tinubu is elected president. |

| Table 1.1 – Nigeria Timeline (created by Matthew Schuster) |

Section 2: Ethnic, Religious, and Cultural Identity

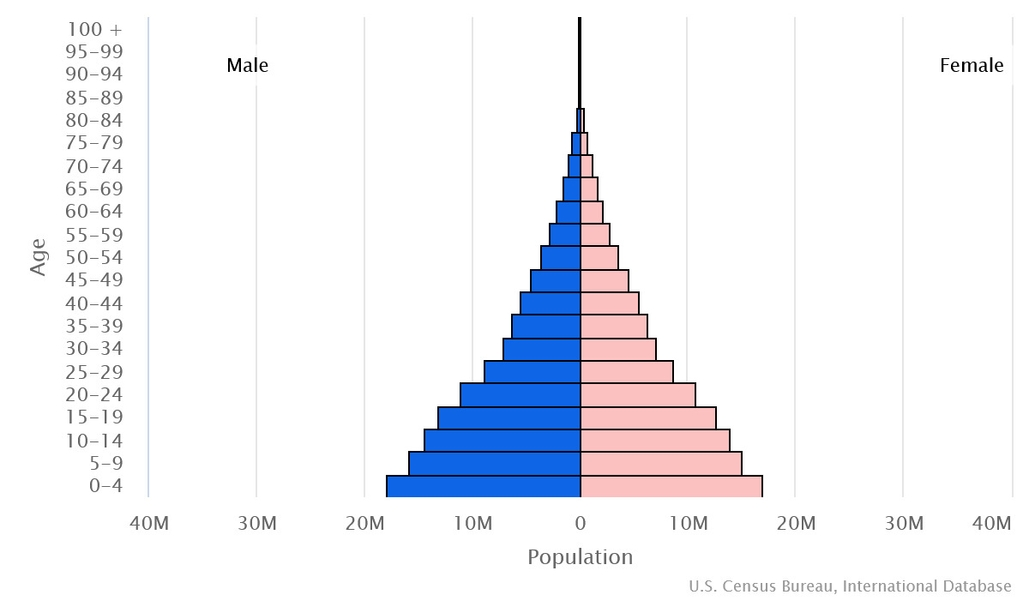

Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa and is the world’s sixth largest country by population behind India, China, the United States, Indonesia, and Pakistan. Current estimates are that Nigeria’s population will surpass Pakistan and Indonesia by 2050 when its population is projected to reach 392 million people. This growth is expected in part due to the age demographics within Nigeria and its high birth rate. The median age in Nigeria is 19 years old. Nigeria has one of the top twenty birth rates in the world with approximately 38 births per year per 1,000 people. Life expectancy at birth is 60 for males and 64 for females. This ranks Nigeria near the bottom of countries in the world in terms of life expectancy.

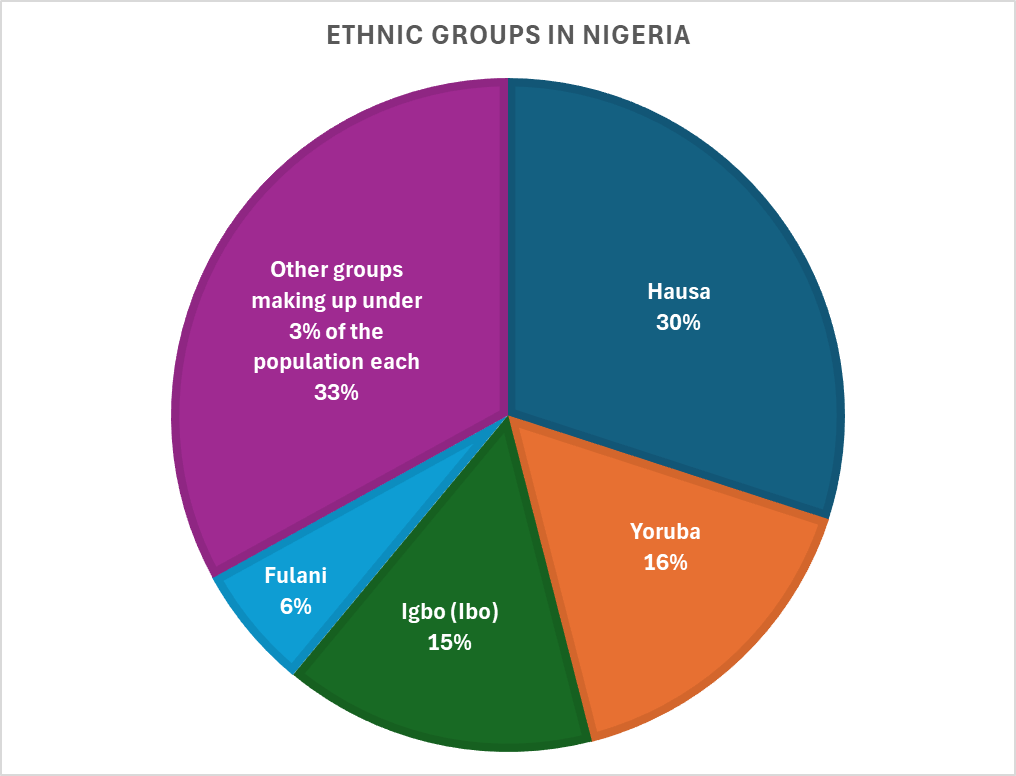

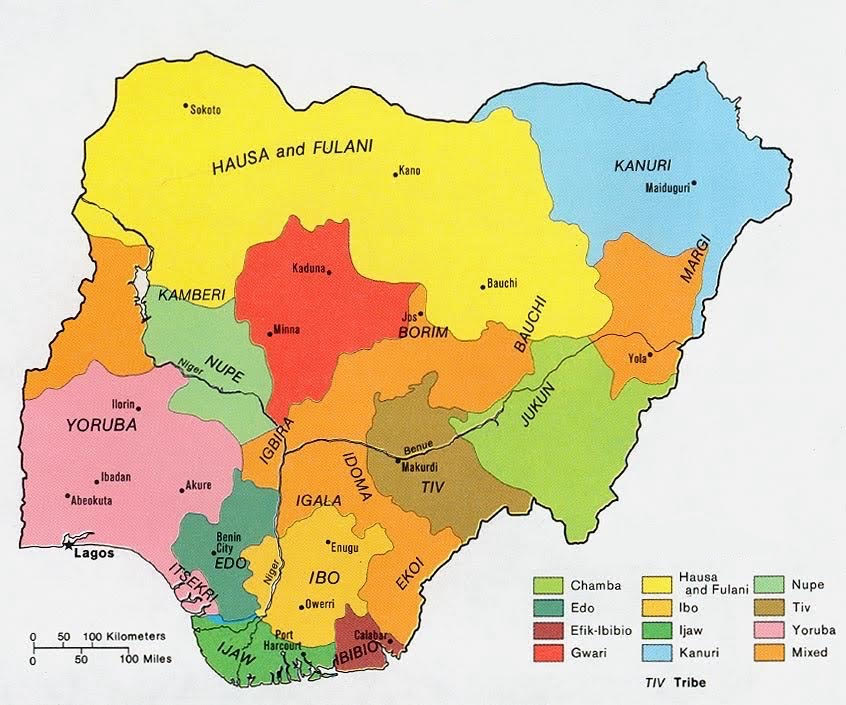

Like most African countries, Nigeria is composed of diverse ethnic, religious, and linguist groups. About 30% of Nigerians identify ethnically as Hausa; about 16% identify as Yoruba; about 15% identify as Igbo (Ibo); about 6% identify as Fulani; about one-third of the population come from a group that make up less than 3% of the overall population. These ethnic divisions are

Like most formerly colonized nations, Nigeria’s borders do not neatly or logically align with its ethnic divisions. Colonizing nations frequently drew borders to place people of the same ethnic groups in multiple countries and to group people of diverse ethnic groups into the same country to make them easier to control. This is easy to see by looking at the three largest ethnic groups in Nigeria. The Hausan are located predominantly in Northeastern Nigeria as well as neighboring Niger. The Yoruba are located predominantly in the southwest as well as in neighboring Benin and Togo. The Igbo (Ibo) are located predominantly in the southeastern part of Nigeria as well as in neighboring Cameroon. While the British colonized Nigeria, France colonized neighboring Niger, Chad, and Benin. Germany colonized Cameroon until after WWI when France and Great Britain controlled it. While France and Great Britain competed and had different styles of colonization, they also worked together to draw borders of the countries of west Africa to make resistance to their colonization more difficult.

Religious divisions are also prominent in Nigeria. Approximately 53.5% of Nigerians are Muslim, 10.6% are Roman Catholic, 35.3% are some other Christian denominations, and about 0.6% follow various indigenous beliefs. The Muslim population is found primarily in the northern part of Nigeria with the Christian population living predominantly in the southern part of the country.

English is the official language in Nigeria and is used by over 50% of the population. English is used in official documents and is the primary language used in mass communication. Despite this, it is not the most common language spoken in Nigerian households. Approximately 31% of the population speaks Hausan as their primary language, 17% use Yoruba, 13% use Igbo, and only 7% speak English as their primary language in the home. Over 500 other languages are also used as people’s dominant languages. The map below shows the historic dominant linguistic/cultural groups by region.

The ethnic, religious, and linguistic diversity in Nigeria have often created sources of tension but could also serve as a source of strength in several different ways. With diversity, comes diverse ideas and values. If properly encouraged and supported, this could enable a marketplace of ideas where the best ideas rise to the top to serve the good of all. With diversity can also come a natural system of checks and balances. Historically, Nigeria has often struggled to maximize the benefits of this diversity but has at times been able to do so to various degrees.

Section 3: Political Culture and Civil Society

Nigerian political culture and civil society are shaped by Nigeria’s size, geographic diversity, ethnic and religious diversity, resources, as well as its colonial and post-colonial history. All these factors have come together to create a country with a history full of strife but also potential.

Nigeria’s diversity is both deep and broad. The northern half of Nigeria is predominantly Muslim. It is also predominantly Hausa and Fulani ethnically. The southern half is predominantly Christian and animist religiously. Ethnically, the south is divided ethnically. The southeast is predominantly Igbo while the southwest is predominantly Yoruba. While these divisions are generally true, they are also imperfect and a vast oversimplification–especially given the existence of over 250 other ethnic groups in Nigeria.

Geographic differences also continue to shape Nigeria’s political culture and civil society. The Niger delta is along the southern coast of Nigeria. The Niger delta is where most of Nigeria’s oil is concentrated. From east to west, the central swath of Nigeria is predominantly savanna/farmable land. The northern strip of Nigeria is steppe/desert. The northeastern corner, mostly desert, contains land that formerly bordered Lake Chad which is disappearing due to climate change and population pressures.

The largest city in Nigeria, Lagos, is in the southwestern part of the country. Lagos is not only the most populous city in Nigeria, it is also the most populous city in Africa and one of the most densely populated cities in the world. It is projected to be the sixth most populous city in the world by 2050. Lagos is divided religiously and ethnically. While predominantly Christian, it also contains a large Muslim population. While predominantly Yoruba, Lagos is like most large metropolitan areas; it is a cosmopolitan city with hundreds of other ethnic groups.

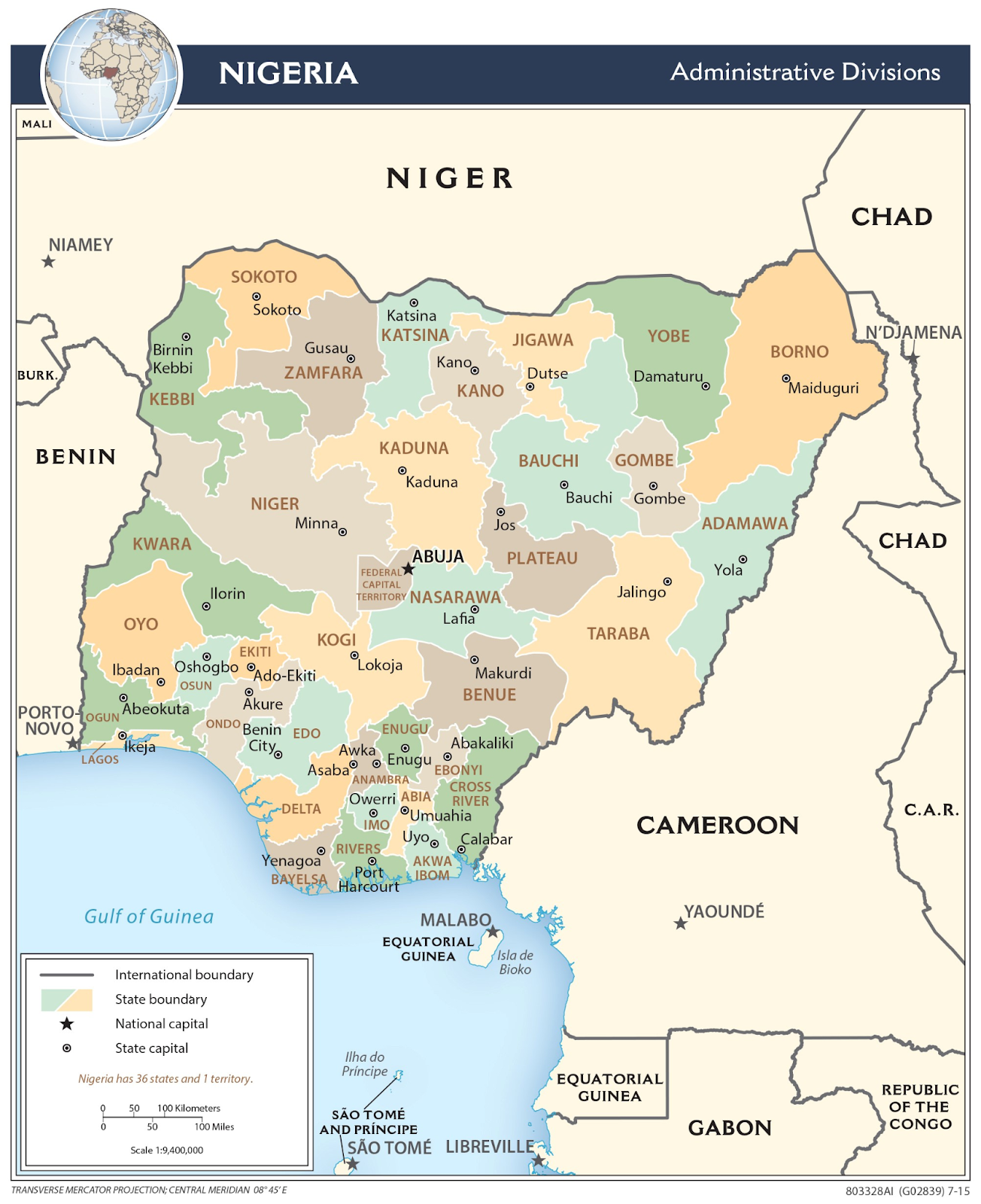

Politically, Nigeria is a federal republic made up of 36 states–none of which align neatly with any specific geographic regions, religious groups, or ethnic groups. Historically different regions in Nigeria have had different sets of rules and levels of power. Under British rule, for example, the northern region was granted relative autonomy and allowed to practice Sharia in non-criminal law. This enabled Great Britain to maintain some control but created divisions among different ethnic groups.

Nigerian diversity is not just broad and deep, it is also dynamic. The breadth and depth can be seen simply by considering how religious, ethnic, and economic regions are not aligned. The dynamism is evident by considering the growth of large cities, especially Lagos, the changing role of oil in the world, and the climate and population stresses throughout Nigeria, especially near Lake Chad. As these changes have occurred, people have migrated throughout Nigeria making any generalizations about Nigeria’s diversity incredibly difficult if not impossible.

This diversity within Nigeria has been both a source of conflict but also an opportunity for potential. Nigeria is home to hundreds, if not thousands, of NGOs ranging from human rights organizations, religious missions, transnational corporations, and terrorist groups, most famously Boko Haram, all looking to have influence on a growing nation.

With its history of political instability, at least until the establishment of the Fourth Republic, including military dictators, religious and economic divisions, economic struggles despite vast resources, and the socially conservative role both Islam and Christianity have played, it should not be overly surprising that Nigeria ranks in the bottom half of countries in the world regarding individual freedom and respect for human rights. Freedom House gives Nigeria a score of 44 out of 100 in terms of individual freedom and a rating of “partly free.” The Human Rights Index, which measures if “people are free from government torture, political killings, and forced labor; they have property rights; and enjoy the freedoms of movement, religion, expression, and association” gives Nigeria a score of .65 on a zero to one scale. The application of human rights is far from universal within Nigeria. Women do not have the same sexual freedom as men with abortion being a criminal act. Members of the LGBT community also lack the same sexual and identity rights as straight and cisgendered Nigerians. Even though freedom of speech, the press, and religion are all constitutionally protected in Nigeria, there has been a history of government control of the press and limitations on what people are able to post online within Nigeria.

Despite these problems, Nigeria has had relative political stability under the current democratic constitution since 1999. While diversity can bring conflict, it can also bring political stability. Since 1999, Nigeria has witnessed five peaceful elections including in 2015 when it saw a peaceful transition of presidential control from one political party to an opposition party. Peacefully transitioning power from one political party to another is always a major test for the strength and stability of a young republic.

Section 4: Political Participation

Nigeria currently has a multi-party system with members from eight different parties making up the current (2024) congress. Despite this, there are two dominant political parties: the All Progressives Congress (APC) and the People’s Democratic Party (PDP). These parties do not fit nicely along a traditional left-right ideological spectrum. Instead, they are more consistent with regional, ethnic, and religious divisions. The APC draws most of its support from the southern Christian population while the PDP draws most of its support from the northern Muslim population. While these divisions are still generally true, they have become less salient in recent years. Historically, more than two parties were dominant and they were often more organized around ethnic divisions than regional or religious divisions.

Political parties organized primarily along ethnic lines began to form during the colonial era and continued during the First Republic (1960 to 1966). Political parties were banned under the military rule until 1976 at which point the military leader General Olusegun Obasanjo legalized political parties and around 150 parties quickly formed. During the Second Republic (1979 to 1983) the constitution required successful presidential candidates to win 25% of the votes in at least two-thirds of the states. This was an attempt to help create national political parties at the expense of regional parties. From 1983 to 1993, Nigeria experienced military rule once again and during the first two years of that rule, political parties were banned. In 1985, Babangida established a two-party system–one to be slightly left of center and one slightly right of center. He then called for an election to hand power over to a democratically-elected, puppet leader. The winner of the 1993 election, a southern Christian was victorious. This marked the beginning, and end of the Third Republic. The northern military rulers declared the election void and would maintain power until another election could happen in 1996. The military leader at the time, General Sani Abacha, called for new elections in 1996. Abachi was nominated by all five of the newly created political parties and, unsurprisingly, Abache won the election. Abacha’s successor, Abdulsalami Abubakar, called for new elections in 1999 creating the Fourth (and current) Republic. Nine parties with national support were allowed to participate but only the three with the most support were able to participate in national legislative and presidential elections. The three parties represented the three largest ethnic/regional groups: The People’s Democratic Party represented the northern Hausa, the All People’s Party represented the eastern Ibo population, and the Alliance for Democracy represented the western Yoruba population. Throughout the Fourth Republic, the parties have evolved in name, number, and platforms. They have also evolved to be less based on ethnic grounds and more along religious/regional grounds.

Nigeria utilizes a presidential system where the president is elected separately from the legislature, the National Assembly. The National Assembly is composed of two bodies: the House of Representative and the Senate. Both the president and members of both chambers are elected on the same four-year cycle. To ensure the president has national support, the winner of the election must receive a majority of the votes as well as one-fourth of the votes in at least two-thirds of the 36 states. If no candidate meets the requirements on the first ballot, a second election is held one week later with only the top two candidates from the first election appearing on the ballot. To ensure that no region would dominate presidential elections, every two terms parties must rotate regions from which they nominate candidates. In other words, the northern-dominant PDP cannot nominate northern candidates for more than two terms in a row and the southern-dominant APC cannot nominate southern candidates for more than two terms in a row. This process is known as zoning. The 360 seats in the House of Representatives are elected by single-member districts. The 109 seats in the Senate are elected by single-member districts with each state getting three districts.

Partly due to its strong regional and ethnic divisions, Nigeria has a long history and tradition of political activism forming along specific interest/identity political lines. Interest groups in Nigeria range from national groups that work with NGOs and IGOs to regional groups centered around the protection of ethnic minorities. Perhaps the most famous of these was the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP). In the 1990s, under the leadership of Ken Saro-Wiwa, MOSOP fought for the interests of the Ogoni in the Niger Delta as foreign interests, especially the Royal Dutch Shell company, profited from the region’s rich oil reserves. Shell worked with the military government at the time to have Saro-Wiwa and eight others arrested, tortured, and hanged.

While regional interests and violent interests still exist in Nigeria, so too do national interests and peaceful interests. Even before the Fourth Republic, but increasing since its formation, these groups have worked independently and with IGOs to promote economic development, democracy, and human rights.

Section 5: Political Institutions

The current Nigerian constitution, adopted in 1999 which established the Fourth Republic, created a presidential system with power shared between the National Assembly, the presidency, and courts. Executive power is vested in the presidency, legislative power rests with the National Assembly, and judicial power resides in the court system. These three divisions of power serve as checks on each other to balance power. Power is further divided between the national government and 36 state governments in a federal system of power that is common in large, diverse nations.

5.1: Federalism

Part one of the constitution creates the federal system with 36 states as well as 768 local government areas. As is common in federal systems, the power between states as well as the power between the states collectively and the national government has varied over time in Nigeria. These variations have been exacerbated because of highly unequal resource distributions, such as large oil reserves in the Niger Delta region, as well as the religious and ethnic differences that have long defined Nigeria’s history and culture. While the national government has supremacy power over the states in Nigeria, the role of the 36 states is fundamental in shaping the National Assembly, the presidency, and the court system. All three branches of the national government take their shape by the actions within the 36 states.

5.2: National Assembly

Part two of the constitution defines the powers of the national government. The National Assembly is the legislative branch of government charged with writing the laws for the nation. The National Assembly is a bicameral legislature containing the Senate (the upper house) and the House of Representatives (the lower house). All members in both chambers are elected to four-year terms with elections taking place for all members on the same day as the presidential election. The Senate is composed of 109 seats. Each of the states gets three senators with one additional senator representing the federal district of Abuja, the capital of Nigeria. The House of Representatives is composed of 360 members drawn from 360 districts based on population. With National Assembly elections coinciding with presidential elections, single-party rule is common in Nigeria. Historically, this has meant that the National Assembly generally supports the president’s agenda.

5.3: The Presidency

Throughout Nigeria’s history, most of the political power has been vested in the executive branch. Since independence in 1960, sixteen men have held power and served as Nigeria’s head of state. Some of these men have come to power as a result of a military coup, some have been appointed by outgoing military dictators, some have been indirectly elected, some have been directly elected by the people, and one was a Vice President who came to power after the president’s death. The First Republic established a parliamentary system with an indirectly elected head of state, Prime Minister Abubakar Rafawa Balewa, in 1960. Most heads of state to follow, from 1966 to 1999, came to power as the result of military coups with the exceptions of Shehu Shagari in 1979 who was elected during the Second Republic and Ernest Shonekan who was appointed during the short-lived Third Republic in 1993.

Nigeria has had five presidents during the Fourth Republic (See table 1). Of these five, they have come from four different ethnic groups. Three have been Muslim while two were Christian. The first three were from the People’s Democratic Party while the last two, including the current president, have come from the All Progressives Caucus. Three of the presidents won reelections to second terms and one, Umaru Yar-Adua, died in office. Along with being the head of state, the president nominates his running mate who becomes the vice president. The vice president assumes office if the president dies–as happened in 2010 when President Yar-Adua died and then Vice President Goodluck Jonathan became president. The President also appoints the ministers of the Federal Executive Council, or cabinet. The Federal Executive Council oversees the implementation of the laws of the national government and is composed of 46 different agencies. The constitution requires at least one minister be appointed from each of Nigeria’s 36 states to help avoid regional favoritism.

|

President |

Years in Office |

Ethnicity |

Religion |

Party |

|

Olusegun Obasanjo |

1999-2007 |

Yoruba |

Christian |

People’s Democratic Party |

|

Umaru Yar’Adua |

2007-2010 |

Fulani |

Muslim |

People’s Democratic Party |

|

Goodluck Jonathan |

2010-2015 |

Ijaw |

Christian |

People’s Democratic Party |

|

Muhammadu Buhari |

2015-2023 |

Hausa |

Muslim |

All Progressives Caucus |

|

Bola Ahmed Tinubu |

2023-present |

Yoruba |

Muslim |

All Progressives Caucus |

Table 5.1 – Presidents of Nigeria since 1999 (Created by the Author)

5.4: The Courts

For most of Nigerian history, the courts have had strong ties to those in political power. Perhaps the most corrupt example of this was the trial and execution of Ken Saro-Wiwa and other activists in 1994 which was discussed earlier in this chapter. Since 1999, though, with the creation of the Fourth Republic, the courts have become more independent and have helped keep some political corruption in check. Since the beginning of the Fourth Republic, the court system has utilized a combination of British common law which is used primarily for its criminal code, customary law which helps preserve the values of its diverse ethnic groups, and Sharia law, predominantly in the northern part of Nigeria, for personal and family matters.

The court system in Nigeria is composed of four tiers. The top tier is the Supreme Court, The Supreme Court is composed of one chief justice and up to 21 other justices as determined by the National Assembly. Justices are appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. They must be qualified to practice law in Nigeria for 15 years before being appointed to the Supreme Court and must retire at age 70. The second tier is a court of appeals. The third tier is the lowest level of federal courts. The fourth tier are all the state courts that are not part of the federal court system. Court cases can be appealed from lower courts to higher courts.

Section 6: Political Economy

Like many emerging economies, Nigeria’s political economy is complex and not easily classified. Nigeria has a mixed economy with certain sectors being heavily privatized, but it also includes numerous public sector activities. With its large, young, and diverse population, diverse geographic regions, and diverse resources, the economy has also proven to be, and will likely continue to be, in a state of relative flux.

The one constant throughout Nigeria’s history over the past 100 years has been how it has experienced a resource curse, i.e., the economic underperformance of a country despite having large quantities of natural resources. Nigeria is rich in oil, natural gas, tin, iron ore, coal, timber, agricultural land, and the potential for tourist destinations. Despite these riches, Nigeria has remained a relatively poor nation. What wealth and economic growth it has experienced has been poorly distributed among the population.

Like many nations which have experienced a resource curse, Nigeria’s experiences go back to the days of colonization under British rule. British interest in Nigerian oil began in 1914 with the declaration that all oil in Nigeria belonged to the British crown. In 1938, Great Britain granted a monopoly to Shell D’Arcy — renamed Shell-BP in the 1950s. Under that monopoly, the company kept 50% of its profits with the British government getting the other 50%. By the early 1960s, other companies, Gulf, Mobile, and Texaco, also began purchasing concessions to profit from Nigeria’s oil reserves.

This colonial history of oil wealth as a source of power has limited Nigeria’s potential to this day. It limited economic growth under British colonization as well as under military dictatorship and all four eras of democratic republics. With most of Nigeria’s oil reserves in just a few south-western states, in and around the Niger Delta region, federalism has never been able to be leveraged to benefit most Nigerians. Military dictators who controlled oil, generally used it for their own benefit. It has only been under the current republic that this has started to change — though that change has been slow to materialize.

Due to Nigeria’s oil reserves, Nigeria was invited to join the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and become its eleventh member-state, and first in sub-Saharan Africa, in 1971. It has been an influential member since then despite Nigeria’s internal political changes.

While oil exports have been a driving force for economic expansion throughout Nigerian history, even if that expansion has not benefited all Nigerians, Nigeria has also worked, with mixed results, on following an import-substitution model of development. That is, Nigeria has restricted global competition to favor local industries. Even before independence in 1960, several local colonial governments worked to develop economically using their own resources. Throughout the 1970s, cement, oil, steel, iron, and a few other industries were the focus of this economic approach. Cement was the only industry that was truly successful at achieving the goals of the import-substitution model. From 2012 to the present, the government has encouraged more industrial production within Nigeria with, again, mixed success.

There have been three major political contexts/time periods that have shaped Nigeria’s economy: colonization, instability between the end of colonization and rise of the Fourth Republic, and the Fourth Republic. During the Fourth Republic, Nigeria experienced broad economic growth (about 7% annually) from 2000 to 20014. This was due primarily to favorable global conditions. From 2014 to 2023, however, due to monetary and exchange rate policy distortions, increased deficits, increased protectionism, and the COVID-19 pandemic, Nigeria has experienced a sluggish economy and increased poverty. In May 2023, the Tinumu administration enacted several changes that have been designed to help improve economic growth. While these changes seem to be working, how sustainable they will be is still to be determined.

Section 7: Foreign Relations

While Nigeria gained independence from Great Britain in 1960, it has remained part of the commonwealth. This link to Great Britain shaped Nigeria’s role in the world during the first half of the Cold War aligning it with the United States and the west. Nigeria moved toward nonalignment during the 1967-1970 Nigerian civil war. During that war, Biafra, in the southeastern part of Nigeria, tried to gain independence. The western allies sympathized with Biarfan independence and did not provide arms to the rest of Nigeria. Despite the lack of support, Nigeria was able to maintain the Biafra region. Throughout the 1970s, Nigeria provided material and diplomatic support to a number of anti-colonial, pro-Communists movements throughout Africa without fully breaking from its western ties.

Nigeria’s role in the rest of the world can best be understood as a series of concentric circles. With Nigeria itself as the innermost circle and West Africa the next largest circle represented by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). ECOWAS was established in 1975 and consists of 16 member states. While the ECOWAS was created to integrate and grow the economies of the 16 member states, perhaps its most evident function has been helping to limit conflict when it occurs. Nigeria is by far the largest member of ECOWAS in terms of population and wealth. With its size and wealth, Nigeria has played an outsized role in supporting peace in the region. Nigeria has dispatched peacekeeping troops to Liberia, Sierra Leone, Côte d’ Ivoire, Togo, and Mali.

Globally, Nigeria has sent peacekeeping forces to Lebanon and along the India-Pakistan border. Much of Nigeria’s political and moral authority was harmed in the mid-1990s with the execution of Ken Saro-Wiwa. Nigeria was suspended from the Commonwealth for three years. Nigeria’s future role in the world, Africa, and West Africa will depend on several key variables including its own political stability, the influence oil and wealth from oil will have on Nigeria, Nigeria’s population, and climate change.

While Nigeria has now experienced over a quarter of a century of political stability under the Fourth Republic, including the secession from one political party to another, the future is far from certain. According to Transparency International, Nigeria ranks 145th out of 180 nations in terms of political corruption as of 2023. Like many African countries, this corruption dates to and is a result of colonization. Regardless of the cause, Nigeria will need to overcome political corruption to reach its full potential.

Related to political corruption, and a common theme throughout Nigerian politics and history, is oil. Nigeria’s oil reserves make it the leading oil producer in Africa. Nigeria’s future will depend in part on how, if at all, it is able to overcome the resource curse and utilize oil for the good of its people. While Nigeria receives the benefits of being an OPEC nation, those benefits, like its oil reserves in general, are not equitably enjoyed by the Nigerian people.

Nigeria’s large and growing population could also have positive and negative effects on Nigeria’s future. A large population, if properly empowered, could prove to be a productive asset for Nigeria. On the other hand, a large population, if not nurtured could create financial and ecological strains on the country. Like many, if not most, emerging countries, Nigeria has faced problems related to climate change even though the people of Nigeria have contributed relatively little to creating the problems associated with climate change. The drying up of Lake Chad and changes to farming patterns have already made life in Nigeria more difficult. As the world transitions away from oil and other fossil fuels, Nigeria will have to deal with the potential decline in a source of its revenue, even if that revenue has rarely been the benefit it could have been.