4 India

Petra Hendrickson

Petra Hendrickson is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Northern Michigan University. They teach a variety of classes in international relations and comparative politics, including introductions to both subfields, genocide, international law and human rights, international organization, East and Southeast Asian Politics, and Eastern European Politics. Their research focuses on mass killing, as well as on pedagogy, particularly the use of simulations and games.

Chapter Outline

Section 2: Ethnic, Religious, and Cultural Identity

Section 3: Political Culture and Civil Society

Section 4: Political Participation

Section 5: Formal Political Institutions

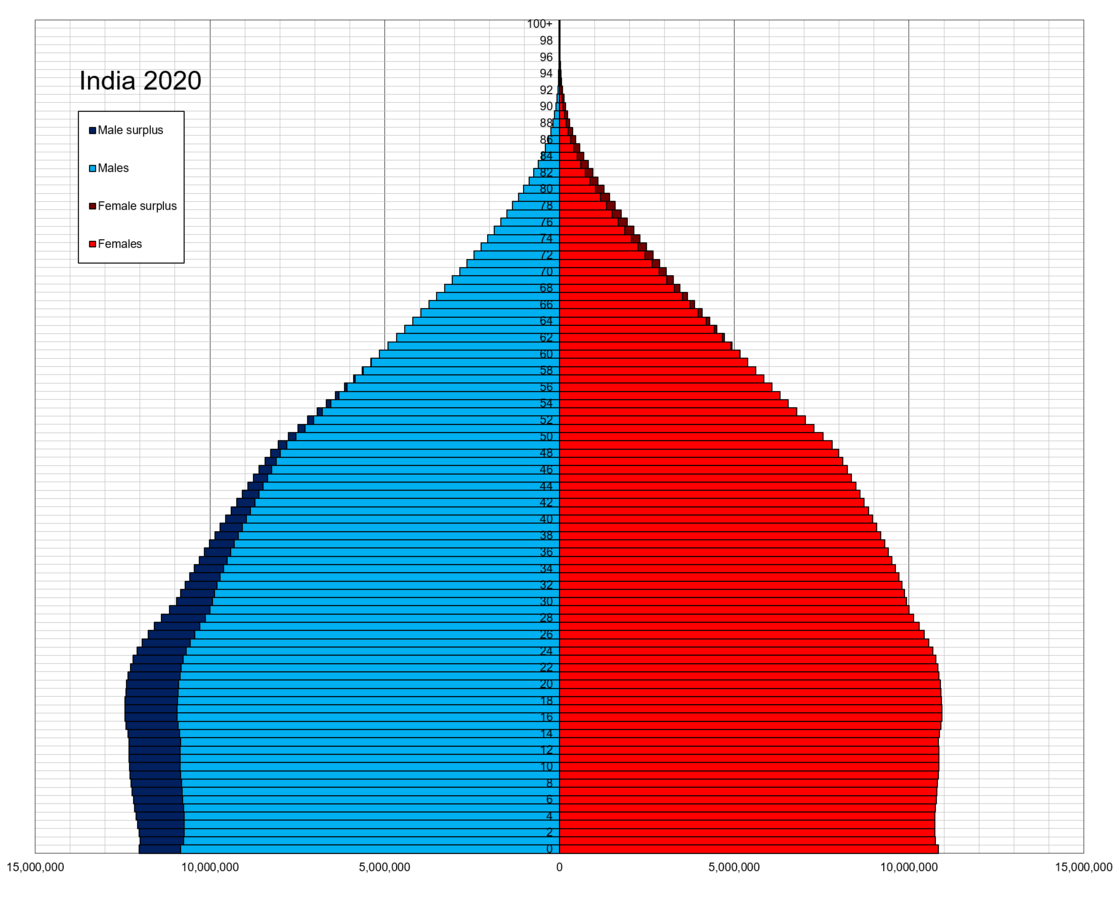

India is both the world’s largest democracy and the most populous country. It is a former British colony, and gained independence in the midst of the contemporary world’s largest population transfer as British India divided into the countries of India and Pakistan. As a leader in South Asia, its political and economic fortunes have the potential to shape those of surrounding countries. Once among the world’s poorest countries, India is now a rising economic power. However, India is not immune from the current global climate of democratic backsliding and has seen rollbacks in minority rights and protections in recent years.

Section 1: A Brief History

Pre-Mughal India (pre-1500s)

Prior to the 1500s, the Indian subcontinent experienced the rise and influence of various religious movements. While Hinduism remains the most dominant and largest within India today, the subcontinent experienced notable periods of Buddhist and Jain influence that developed internally. Prior to the eighth century CE, other groups, like the Aryans, Greeks, and Scythians, spread their influence eastward into the subcontinent. Islam emerged as a religion in the seventh century and made it to what is today northwest India by the 680s CE alongside expansions of various empires, such as the Persian, Afghan, and Mongol empires. The Mongols (also called the Mughals) became the most dominant of these later arrivals, eventually ruling vast swathes of the subcontinent.

Mughal Empire (1526-1857)

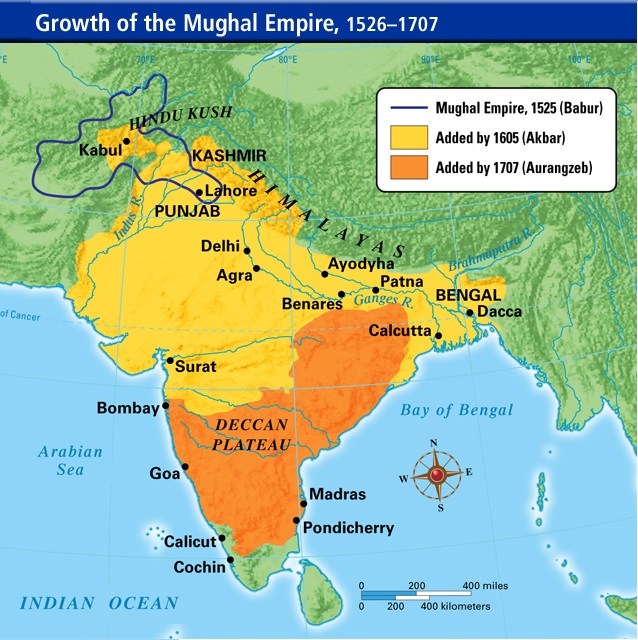

Although its rulers were Muslim, the Mughal Empire governed a religiously diverse population with a degree of liberalism, rather than requiring conversion to Islam, and governed in part by building on already-existing indigenous governance structures, including non-Islamic legal systems. As the pre-Mughal history suggests, India has long been home to a variety of religious traditions that have peacefully coexisted and cooperated; the rigid delineation between groups, practices, and power that encouraged conflict really emerged later, under the British.

The Mughals unified what had been numerous smaller monarchies throughout the subcontinent, expanding and consolidating its control from 1526-1707, when the empire reached its peak strength. The gradual weakening of the Mughal rulers paved the way for the rise of other social actors, like revenue farmers, merchants, and bureaucrats, marking a decentralization of power in the Empire. The economy still generally prospered during this time through the middle of the 1700s. In 1770 and 1783, portions of India experienced famines, which also coincided with periods of increased European, and especially British, colonial activity.

India as British Colony (1600s-1947)

The first British incursions into territories on the Indian Subcontinent occurred in 1608 by the British East India Company, which was formed in 1600 with the express goal of expanding British trade. The British East India Company would increase its involvement in the country over the next 150 years, until its activities in India were subjected to closer oversight by the British government and India itself placed under the control of a British Governor-General in 1773. Following this, British control of India increased – taxation systems were set up for the British to collect revenues from local rulers, the amount of territory controlled by the British increased, and various ethnic and religious groups in the subcontinent were subdued through armed conflicts against British troops. In 1857, the most widespread of these anti-British uprisings, the Sepoy Rebellion, occurred. While the final spark was the introduction by the British of bullets rumored to be greased with pig and cow lard (thus violating both Islamic and Hindu religious rules), tensions had been building since the early 1820s and the introduction of British paramountcy, or dominance over Indian politics, economics, and culture. The British responded to the mutiny with excessive violence and gruesome executions of those suspected of involvement. The rebellion highlighted to the British that more direct control over Indian affairs was necessary. In 1858, the East India Company was dissolved altogether, and governance of India became a matter for the British government itself, as opposed to a private company acting under the authority of the British government. This handover from the British East India Company to direct British control over the governance of India marked the period of history known as the British Raj, which continued until India’s independence.

During this time, the British consolidated their control over India, with each of British India’s provinces led by a governor. The government of the Raj was made up exclusively of British officials, although small numbers of Indians were appointed to serve in consultative roles. During the Raj, the British parliament passed nearly 200 laws concerning India. There was also backlash to British rule during this time, and an Indian nationalist movement aimed at self-rule emerged beginning in the mid-1880s. Two Indians were members of the British parliament during this time, though they were not agreed on the issue of Indian nationalism – one member was one of the founders of the Indian National Congress while the other supported the British Raj. Beginning with an 1892 law, Indians were allowed to be elected to legislative positions in the Indian government, and a 1909 follow-up law increased the representativeness of these officials along religious and social lines.

British India, which at its largest included all or part of current-day India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Myanmar, was extremely important to the British colonial mission, and it was said that India was “the Jewel in the Crown” of the British Empire. India was Britain’s oldest and most profitable colony, and India’s independence in 1947 began the longer process of the dismantling of the British colonial system that occurred into the 1960s, when many African and Asian territories gained their independence.

Other European Colonial Influences

In addition to the British, the Portuguese, Dutch, and French also made colonial inroads into India at various times.

The Portuguese were among the first European colonizers to come to India, in the late 1400s, and were the last to give up their colonial holdings, vacating Goa only in 1961 after an Indian military operation. Their main area of influence was the central western coast of the country, including Bombay (now Mumbai) and the contemporary states of Maharashtra and Gujarat in the north and west and Goa in the south. Portugal was second only to the British in their influence in India – although the Dutch and French held territory, their colonial possessions were much smaller in scope and were more historically isolated. Goa was the center of Portuguese power on the subcontinent as well as a social center as well. The Portuguese court, military, and church all headquartered in Goa, and Goa held a status similar to Lisbon, the capital of Portugal. The arrival of the Dutch in India in the early 1600s, with their blockade of Goa, marked the beginning of the decline of Portuguese influence, although as noted above, the Portuguese would retain a presence on the subcontinent until the early 1960s.

The Dutch, in the form of the Dutch East India Company, arrived in India in the early 1600s and established trading posts on both the west coast (Surat), and east coast (Bengal) of the subcontinent. They also installed military troops along the Malabar coast in the mid-1600s to protect against invasion by other powers. However, the primary Dutch interest in south and southeast Asia was in modern day Indonesia and Malaysia, and lost many of their territories to the British in a series of treaties, forfeiting almost all of their trading posts by the mid-1820s.

The French were the last main colonial influence in India, arriving in the 1660s. They always possessed far less territory than the other colonial powers. They also established a trading post at Surat in the west, though their primary area of influence was Pondicherry, on the southeast coast. The French were primarily interested in trade, rather than outright occupation and rule, until the 1740s, when French politics moved in favor of expanding the French empire into India. However, France began losing ground to the British in conflicts beginning in the late 1750s, vacating India completely beginning after independence, leaving its last areas of control in 1954, with a treaty recognizing these transfers of power ratified in 1962.

Independence Movement, Changing Colonial Policy, and Independence (1860s-1947)

With the transition to the British Raj, an independence movement emerged to end British rule in India altogether. The independence movement gathered pace and was especially active beginning following World War I.

Beginning in the 1860s, British allowed areas of India to be governed by provincial councils that incorporated Indians on a non-official consultative basis. These councils spread from Bengal, Bombay, and Madras to most provinces by the early 1880s, and the number of Indians on the councils, still in a non-official capacity, also increased over time.

The Indian National Congress, the largest nationalist organization, was formed in 1885 and initially sought elections for the provincial councils and increased representation of Indians in the administrative bureaucracy – efforts which met with only modest success. The British doubling down on imperialism in the late 1890s and early 1900s provided justification for a more hardline Indian national movement. British attempts during the same period sought to increase discord between Hindus and Muslims by creating a separate Muslim-majority province, Bengal, and encouraging the creation of the Muslim League, a Muslim nationalist organization, in 1906.

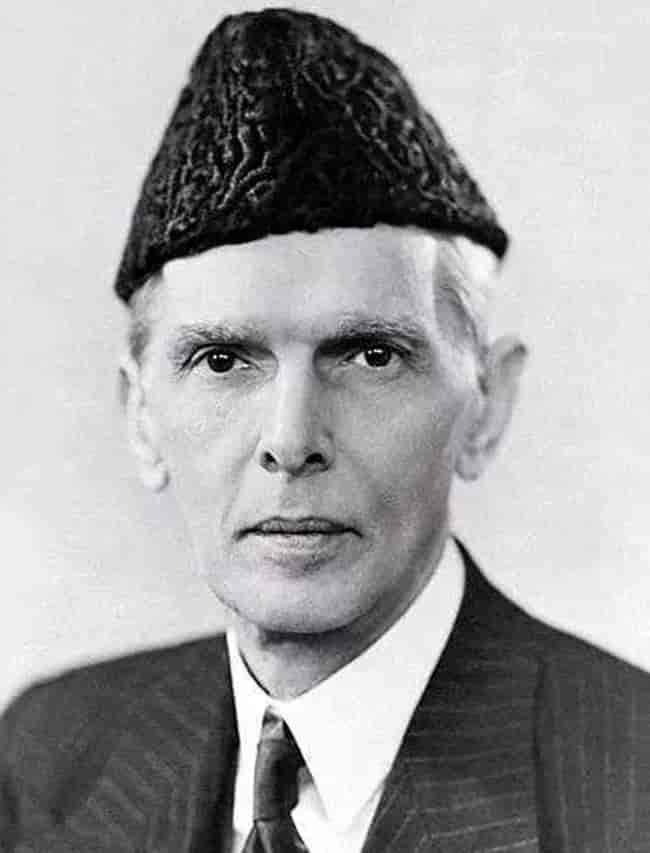

Bengali elites opposed the politicization of religious (as opposed to national, as Indian) identity, and a swadeshi (own country) movement emerged to oppose such societal and geographical divisions. Both moderate and more radical Indian nationalists joined together in the swadeshi movement, cooperating in actions like a boycott of British goods in 1905-1906. However, the nationalist movement eventually split, with the moderates retaining calls for autonomy and self-rule, and radicals calling for outright independence. Britain annulled the partition of Bengal in 1911, which also led to the increase in the professionalization of Muslim nationalism in the leaders of the Muslim League like Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

Over 1 million Indian soldiers fought for Britain during World War I. Calls for autonomy, self-rule, and outright independence subsequently increased after the war, marking a shift to a more consistently active phase of the independence movement, with periods of increased cooperation between moderates and radicals and the Indian National Congress and the Muslim League during the war.

Britain granted some liberalization of Indian governance from 1919-1935, but kept the vast majority of power in British hands. The 1935 Government of India Act accepted the notion of a united (Hindu and Muslim) Indian federation, increased voting rights, and granted the provinces more autonomy; Indians were also given increased power in the provincial councils, officially participating in all areas of their governance. However, there was no transfer of power regarding defense or foreign affairs.

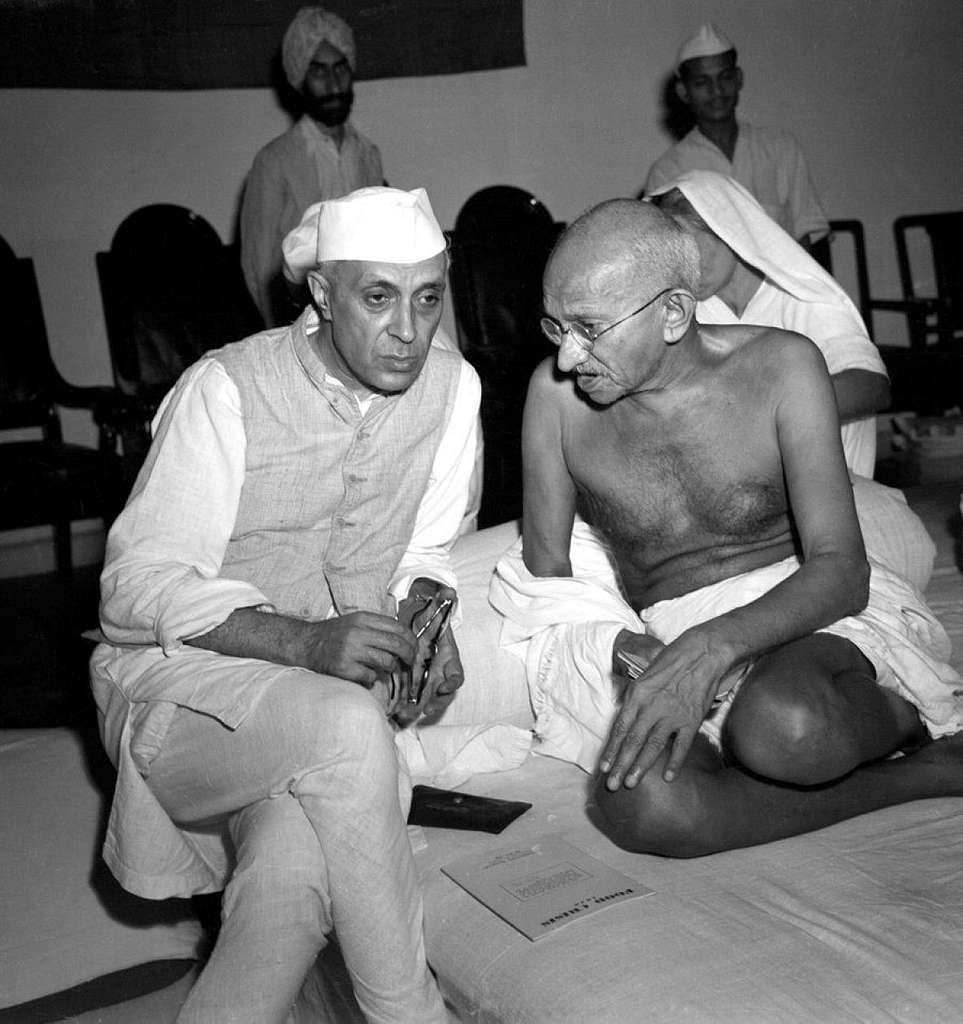

Mohandas (Mahatma) Gandhi emerged as a leading nationalist figure during the 1920s and 1930s, and sought a united India of all people within British Indian borders, regardless of religion, and, within Hindu, caste. Not all nationalist activists agreed with this vision. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, who would go on to chair the committee that drafted the Indian Constitution, was himself a Dalit and advocated against untouchability and for expanded rights for Dalits. His own eventual conversion from Hinduism to Buddhism prompted large numbers of other Dalits to do the same. Gandhi’s glossing over of real, existing divisions in Indian society under a banner of nominal “unity” also prevented some of those divisions from being addressed in ways that might have made the scale of the eventual rupture smaller.

Additionally, Gandhi’s explicit drawing of religion into politics alienated Muslim League leaders who sought unity between Hindus and Muslims without directly invoking religion. Gandhi nonetheless also emphasized issues that created cross-cutting cleavages among India’s various groups, fostering cooperation on issues like non-payment of rents and revenue to the British.

Radical nationalists in the Indian National Congress, like Jawaharlal Nehru, tried to get Gandhi to argue for outright independence instead of increased autonomy, but Gandhi helped defeat a 1928 Congress resolution calling for complete independence. The Muslim League and Congress cooperated against the British until 1937, when the Muslim League was spurned by the increasingly radical nationalist Congress Party.

Perhaps the most famous, though by no means the only, civil disobedience movement led by Gandhi was the Salt March of 1930, which was a protest against British control over the sale of salt. Gandhi and others embarked on a march to the sea where they then made their own salt, from the salinated seawater, breaking British law in doing so. Gandhi was arrested for his role in organizing and leading the march, but he did not stop his calls for nonviolent resistance to British rule.

Before World War II, the Indian National Congress was split into conservative and radical factions, while a separate Muslim nationalism, under the leadership of Jinnah and the Muslim League, was increasing, pushing the predominantly Hindu Congress and the Muslim League further apart politically.

India again contributed vast numbers of soldiers – roughly twice as many as in World War I – and amounts of materiel to the British effort in World War II. Britain’s clear reliance on Indian troops coupled with its refusal to grant self-rule led to the Indian National Congress launching its Quit India movement in 1942. Gandhi organized this campaign as well, now solidly on the side of independence and a withdrawal of the British from the subcontinent. While Gandhi himself participated only in nonviolent resistance in the face of British crackdowns on the movement, he stopped speaking out against protestors who used violence, arguing that the British were the responsible for the violence by the act of their presence in India.

Britain was considerably depleted – especially financially – after World War II, severely constraining its ability to maintain its previous level of occupation and control over the subcontinent. Nationalist calls for independence increased, and the Indian National Congress and Muslim League moved further apart politically, with the Muslim League eventually calling for a separate, independent Muslim state. The British ultimately backed this plan for partition, although the mechanisms by which millions of people would relocate across new national borders were unclear until after Pakistan declared independence on August 14, 1947, and India declared its independence a day later, on August 15, 1947. Jawaharlal Nehru became the country’s first prime minister upon independence, governing until his death in 1964. In January 1948, Mohandas Gandhi was assassinated by a Hindu hardliner who was angered by Gandhi’s politics of inclusivity, including Muslims.

Partition

The reorganization of territorial possession and new international borders in what had previously been a unified British India, called Partition, had devastating consequences for all major groups in India. Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs faced displacement and forcible evacuation while also inflicting these acts on other groups as the populations sought to be on the “right” side of the new border between India and Pakistan. Punjab in particular was itself partitioned between Pakistan and India, with Pakistani Punjab forming the core of that new country. Moreover, Pakistan was divided into two non-contiguous sections, with East Pakistan comprised of East Bengal (West Bengal is in India), separated by a large piece of India from West Pakistan, located in India’s northwest.

Even before the formal declaration of the Partition plan by Lord Mountbatten in June 1947, thousands of people were killed in Bihar and Calcutta (now Kolkata, in what would become West Bengal). During the weeks and months of the Partition process, riots, abductions, and other atrocities occurred, affecting especially Muslims and Sikhs, as the widescale population transfers unfolded. All told, hundreds of thousands of Muslims were killed, blamed for the division of India. Additionally, the population movements shifted (West) Pakistan’s population from 49% Muslim in 1941 to 97% Muslim in 1951. East Pakistan faced a smaller shift shifted from 71% Muslim in 1941 to 75% in 1951 (Hodson 1969).

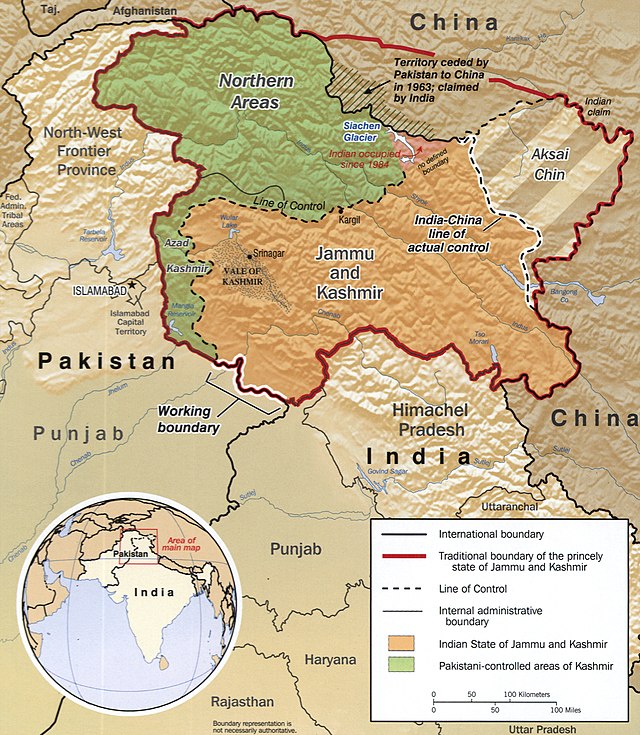

India and Pakistan also failed to reach agreement on the distribution of certain pieces of territory, namely the province of Kashmir, which both countries have laid claim to since they became independent and remains a constant source of tension and competition between the two countries. Kashmir traditionally had a majority Muslim population, but a Hindu ruler, complicating the increasingly politicized narrative of Muslim vs. Hindu in Indian politics. Multiple full-blown wars have been fought over control of Kashmir, with the territory itself functionally partitioned (already the product of partition between India and Pakistan) between areas under the control of India, Pakistan, and China. Nonetheless, this status quo remains unstable and prone to skirmishes between Indian and Pakistani military troops.

The Congress Dominance (1964-1977)

At independence, the Indian National Congress was the single largest political party in the country, and the one most able to compete at all levels of government. From Nehru’s taking the helm as prime minister at independence through 1996, the Congress Party dominated national politics in India. So, too, did Nehru’s descendants – his daughter Indira Gandhi (no relation to Mohandas), became prime minister in 1966, two years after Nehru died in office – dominate the Congress Party. From independence through the 2024 general election, a member of the Nehru-Gandhi family has been in charge of the Congress Party almost continuously.

Indira Gandhi, riding the popularity of and affection for her father, was re-elected prime minister following elections in 1967. Although Congress popularity was diminished in that election compared to previous elections, Gandhi was able to rule without a coalition, and took an increasingly hardline, s well as personalizing politics more explicitly, leading a faction of the Congress Party when it split due to internal divisions in 1969. Gandhi called for new elections at the end of 1970, and used those elections to shore up her own power. A period of unrest broke out in 1974, and in 1975, the High Court of Allahabad ruled that her 1971 election victory was invalid due to her use of state materials during her campaign. In response, Gandhi convinced the president to declare a state of emergency, granting her broad powers to repress her political opponents, including through imprisonment, censorship, and mass sterilization.

The Emergency, as it has come to be known, seriously undermined India’s claims to be a democracy, and lasted until the 1977 parliamentary elections. In that campaign, Gandhi’s branch of the Congress Party failed to win a plurality of votes, and Gandhi was replaced as prime minister by Mararji Desai, of a new political party, the Janata Party, which had combined the other Congress faction, the Jana Sangh, the Socialist Party, and the Bharatiya Lok Dal.

1.8 Congress Decline (1977-2014)

The Desai government sought to undo some of the damage to democracy of the Emergency, including unbanning organizations and repealing censorship laws. However, the biggest factor unifying the opposition to Gandhi was that opposition itself, and the Janata Party also split into factions, paving the way for Indira Gandhi to return to power in 1980 as the head of a new Congress Party explicitly aligned with her – Congress Party (I[ndira]).

Upon her return to power, in February 1980, Gandhi invoked a constitutional measure known as President’s Rule to remove state governments from power and impose national rule in nine states controlled by the opposition or which had not had state-wide elections in the past two years.

In 1984, the followers of the leader of a Sikh separatist movement in Punjab state occupied the Golden Temple in Amritsar, which was the primary Sikh holy place. Because of the loss of a significant portion of Punjab, any further loss of control over Punjab was seen as unacceptable by the Indian government. In July 1984, a national order, called Operation Blue Star, was given to retake the temple through force, angering the Sikh community because of the functional attack on their holy site. In October, Gandhi was assassinated by two of her Sikh bodyguards, which then prompted retaliatory killings of Sikhs by the Congress Party.

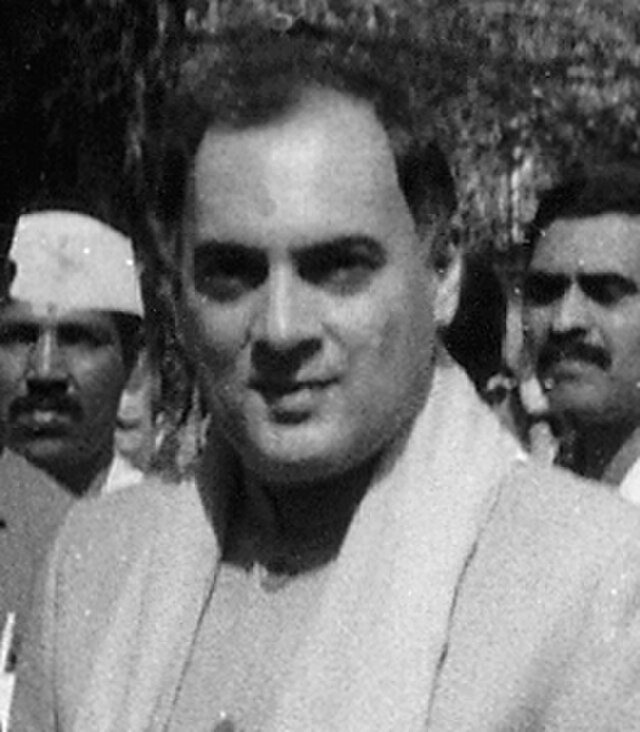

Though Gandhi has been unable to make the Congress Party more popular, her assassination created a groundswell of support for the party, which earned its highest vote share to date in the December 1984 parliamentary elections. Rajiv Gandhi, Indira’s oldest son, who had taken her place in power after her assassination was returned to power as prime minster after the election. Rajiv Gandhi’s period of rule was marked by a settlement with the Sikh leader whose followers had occupied the Golden Temple and an attempt to reduce corruption, though he was himself accused of corruption in 1987. The Congress Party lost its hold on power to a coalition of the Janata Dal, Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), and communists in the 1989 election.

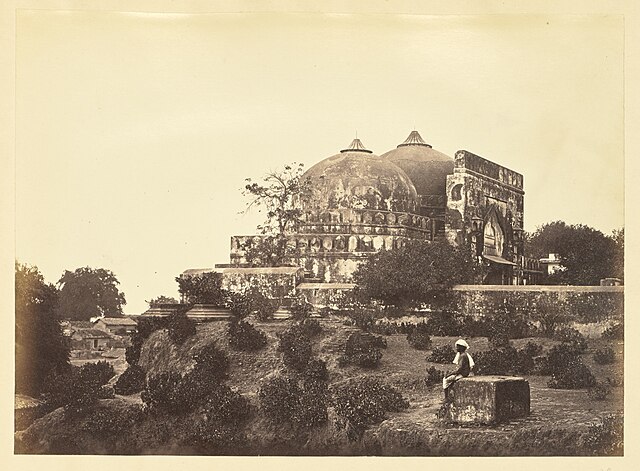

New prime minister VP Singh was seen as more of a technocrat, or skilled in technical expertise rather than true political savvy, announced the implementation of the recommendations of the Mandal Commission, which was created in 1979 and released a report in 1980 that sought to improve the social, economic, and political position of “Other Backward Castes,” which comprised a majority of the Indian population. This announcement was very unpopular with high-caste Hindu nationalists, including the BJP, which had campaigned in 1989 on the issue of building a temple on the grounds of a mosque that had been built in Mughal times in the Uttar Pradesh town of Ayodhya. This proved to be a popular campaign issue, and the BJP increased the number of seats in won in 1989 to 88 (up from two in 1984). As BJP’s inroads during this period suggests, there was also increasing Hindu nationalist rhetoric and activity, including vigilantism against Muslims for various perceived, rather than actual, crimes, during the Singh administration.

In 1990, the president of the BJP led a demonstration against the Ayodhya mosque, though he was arrested before he could arrive at the mosque and construct a temple in its place. In response to his arrest, Hindu militants took control of the mosque, which sparked a counterattack by the national government. In light of this, and the announcement of the Mandal Commissions recommendations, the BJP withdrew its support of the Singh administration, prompting new elections in 1991.

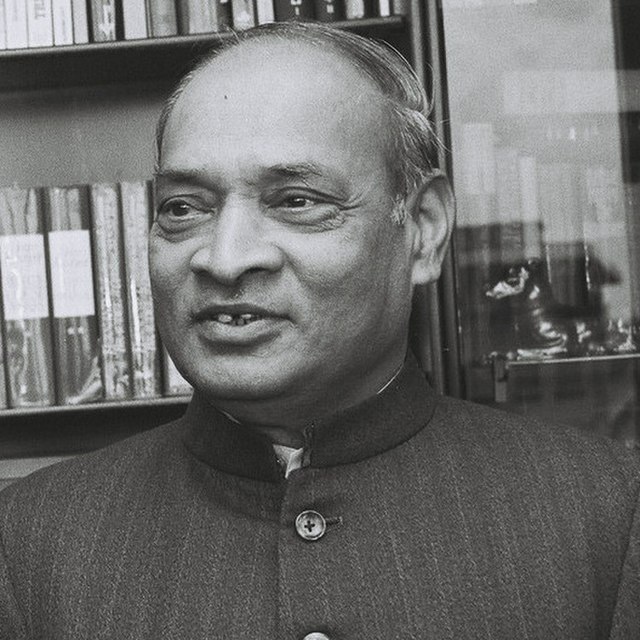

Although in competition with each other, the joint power of the increasingly influential lower castes as well as upper-caste Hindu nationalists also meant a decline in the overall popularity of the Gandhis’ Congress Party. Nonetheless, Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination on the campaign trail in 1991 propelled the Congress Party (I) back into power, though short of an outright majority in the lower house of parliament. PV Narasimha Rao, who became prime minister, oversaw a period of economic liberalization and the move away from the extremely inefficient and economically hobbling “Licence Raj” system for private businesses. Rao and Congress lost further ground among the lower castes (for not implementing the authorized Mandal recommendations) and Muslims (for allowing the destruction of the Ayodhya mosque), declines which primarily benefitted the BJP in the 1996 elections.

The BJP was the largest party in the lower house after the 1996 election but lacked a majority. As neither Congress nor the BJP could rule without a coalition, a group called the United Front, with support of Congress, took power. However, the Congress Party (I) remained wary of the United Front’s hold on power, and forced the prime minister to resign, doing so again when the new prime minister was appointed, triggering elections in 1998. The BJP gained seats in the 1998 elections, but the parties experiencing the most growth in the lower house were regional parties, which more than tripled the number of seats they collectively held.

The BJP-led coalition ruled without significant parliamentary drama, the first coalition to do so. During this term, prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee oversaw the testing of nuclear weapons, anti-Muslim violence by Hindu nationalists, and closer ties to the United States.

In 2004, the Congress Party, now led by Rajiv Gandhi’s widow Sonia, returned to power as part of a coalition. Sonia Gandhi declined to become prime minister out of concern that her Italian heritage would be weaponized by the Hindu nationalist-BJP, leaving Manmohan Singh to become prime minister. Singh most notably continued India’s move toward economic liberalization.

In the 2009 elections, Congress again won the most seats, followed by the BJP, with regional parties again gaining ground. In this term, Singh’s administration faced numerous accusations of corruption which greatly diminished its ability to govern, as well as its popularity. After hobbling along for years, new elections were held in 2014.

In this election, the BJP won, with Narendra Modi at its head, seeming to mark a new era in Indian politics less based on party competition and more based on ethnoreligious nationalism and single-party dominance, which will be considered throughout the remaining sections of the chapter.

Section 2: Ethnic, Religious and Cultural Identity

2.1. Official Languages

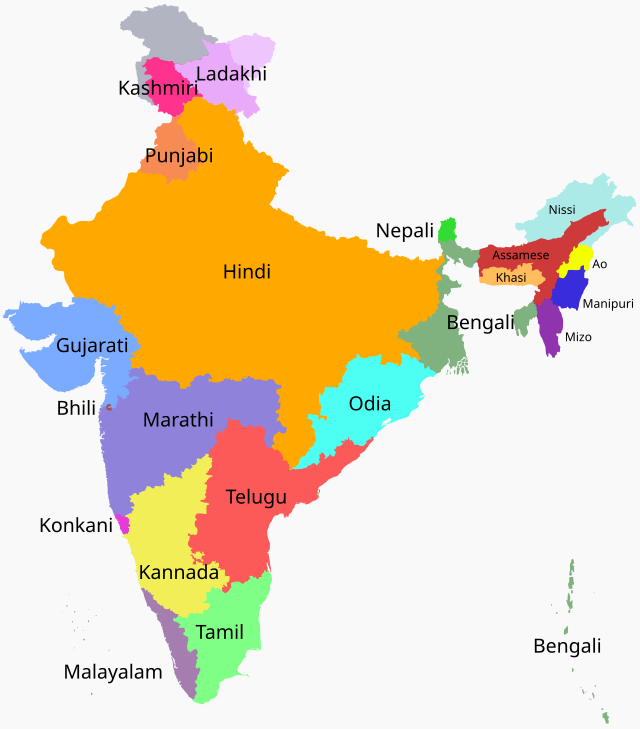

India has no national language and 22 official languages, largely associated with states. However, many more languages and dialects are spoken throughout the country. The two official languages of India spoken by the most people are Hindi and English, which jointly serve as the lingua francas in the country. English has traditionally served as the language of the elites and the administrative apparatus, although Prime Minister Modi announced in 2022 that he would use Hindi to conduct all official government business. That announcement coincided with a report from a parliamentary committee that recommended the use of Hindi as the language of instruction in higher education in Hindi-speaking areas, and the use of vernacular or regional languages in the same academic settings elsewhere in the country, with English as an optional language. These recommendations have been controversial in parts of the country where Hindi is not the dominant language (Salomone 2022). The Modi administration also adopted a policy in 2020 that promoted education in vernaculars with gradual shifts away from mandated English education. Because of the mixture of regional languages, the linguas franca, and Modi’s new push of Hindi, there is a high degree of bi- and multilingualism in the country.

2.2. Linguistic and Ethnic Groups

India’s various languages call into four broad linguistic families: the Indo-Iranian subfamily of Indo-European languages (central and northern India), the Dravidian family (central and southern India), the Austroasiatic family (eastern India), and the Tibeto-Burman subfamily of Sino-Tibetan (northeast India). Most languages in the country fall into the Indo-Iranian or Dravidian language families.

India’s ethnic groups can be broken into three main categories that correspond in part to the geographic distribution of the language families: Aryan, Dravidian, and indigenous. The Aryan groups largely reside in the northern part of the country, while people of Dravidian descent primarily live in the southern part of the country. The indigenous communities comprise the groups legally recognized as Scheduled Tribes, and have received many of the same legal protections and political programs as the Scheduled Castes, discussed more in Section 2.4

For both language and ethnicity, broad distinctions can be drawn between the northern and southern parts of the country, although many of the indigenous groups also living in the central part of the country, running from west to east across the width of the country.

2.3. Religious Groups

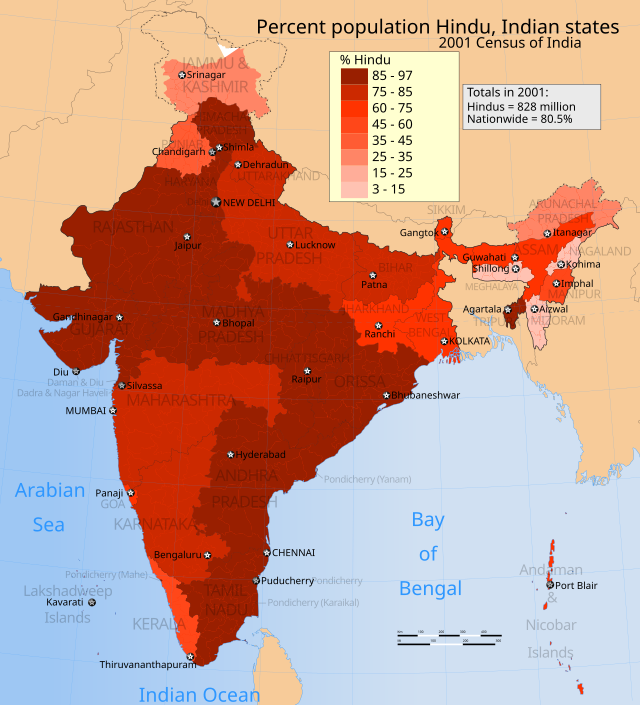

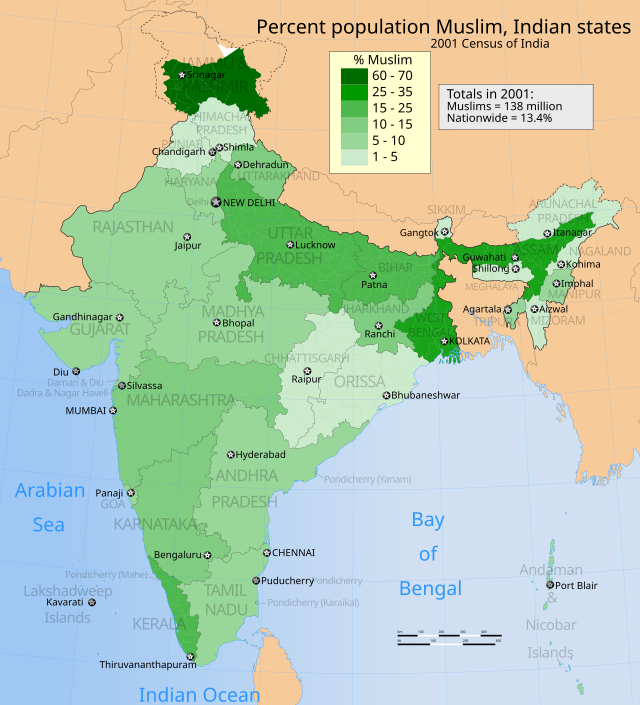

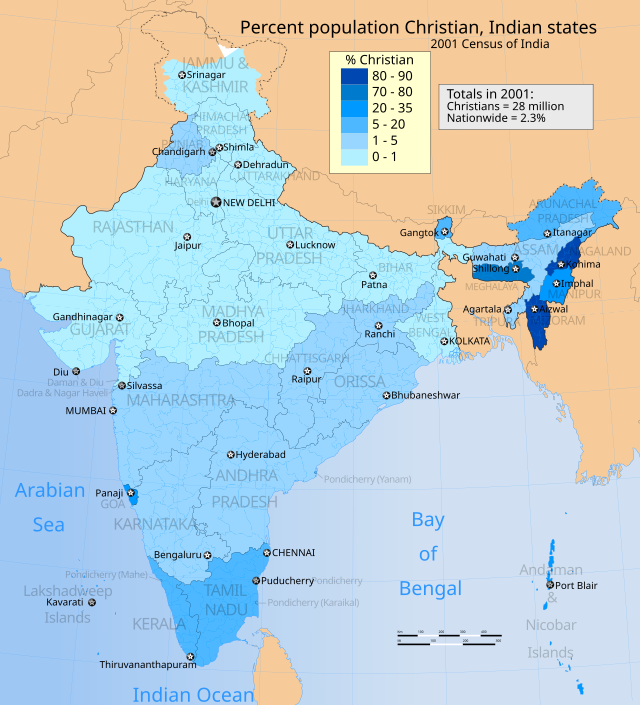

Although India is constitutionally recognized as a secular state, religion and religious identity plays an important role in the country. The two largest religions in the country by far are Hinduism (~80% of the population) and Islam (~14%), with notable populations of followers of Christianity (~2%) Sikhism (2%), Buddhism (0.7%), and Jainism (0.4%). Since before independence, religion, and especially the division between Hindus and Muslims, has been India’s most salient identity category and the one most prone to violence (see sections 2.5.1 and 2.5.2 for more about Hindu supremacy and religious violence).

While religions like Christianity and Islam are found worldwide, Hinduism, Sikhism, and Jainism are more geographically concentrated around India.

Hinduism is actually a diverse set of religious beliefs, united in the belief in a supreme deity that is omnipresent, both in the universe and within people. In part because of its internal diversity, Hinduism does not have the degree of formal institutionalization as other religions, such as many Christian and Muslim denominations. It also holds that people are intrinsically divine and that people’s purpose in life is to seek out and recognize that divinity. Other key beliefs of significant portions of Hindu traditions are in a continuous cycle of life, death, and reincarnation, and in karma, which holds generally that the actions people take have consequences, and that good actions are more likely to lead to good outcomes, while bad actions are more likely to lead to bad outcomes, reflecting a sort of cosmic balance. Karma determines the path one takes during the cycle of life, death, and reincarnation.

Sikhism emerged in the 1400s by Guru Nanak, who developed a religious doctrine based on egalitarianism and social justice, which he viewed as standing in contrast to both Hinduism and Islam. In 1699, a community known as the Company of the Pure emerged within Sikhism that became more associated with a warrior stance, marked by “the five Ks, taken from the words kesh (uncut hair), kangha (comb), kirpan (sword), kara (steel bangle) and kaccha (breeches)” (Minority Rights Group 2023). Sikhs were important members of the British Indian Army during the colonial period and at times have called for a Sikh state that was independent of India.

Jainism and Buddhism emerged as reactions to some interpretations of Hinduism, and generally hold that all living beings, people, animals and plants alike, have souls, and that the path to enlightenment lies in nonviolence and the minimizing of harm and violence against living things. Jainism and Buddhism also believe in reincarnation, or rebirth, and a person’s path and social position being determined by their karma.

2.4. Caste System

The caste system, throughout South Asia, was originally more diverse, with multiple local caste systems existing throughout the region, and operating more as a system of marriage restrictions, as opposed to a hereditary position. is a ranked hierarchy of social groups in India.

Much of the function and role of the caste system in India today has been shaped by the British colonial interpretations of and interactions with the caste system, creating a standard interpretation of what the caste system was and its implications. This formalized the caste system’s role and importance in society and politics in a way that frustrated India’s founding fathers, especially Nehru and Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar. Ambedkar also helped draft the constitution of India and was the minister of Law and Justice in Nehru’s first cabinet. These men, and other leading Indian intellectuals, viewed the caste system as a barrier to social and political equality and progress in the country, and hoped its importance would rapidly decrease to nothing. This is not what happened, and although the Indian constitution prohibits discrimination on the basis of a variety of social identities, including caste, and a number of affirmative action programs exist to increase opportunities for lower caste individuals, the caste system continues to play an important role in organizing Indian society, especially in rural areas, and influencing the social mobility of Indians.

As the British interpreted it, caste status is passed down hereditarily, with children taking on the caste of their parents. Caste has traditionally been associated with particular occupations. There are four main caste categories, with each main category containing a number of sub-categories. The highest-ranking caste is the Brahmans, followed by the Kshatriya. The Vaishyas are third in the hierarchy, ranked notably below the Brahmans and Kshatriya, but still considered high enough to be entitled to a “second birth” that would grant them access to special rituals and religious knowledge. The lowest ranking main caste are the Shudras, who are much lower than the Vashiyas, but still in the caste ranking system. There were also historically people in occupations dealing with human waste, such as sanitation workers, were deemed so low in society as to be outside the caste system altogether and were classified as “untouchable.” Individuals in this category are also called Dalits, and in Indian legislation, they are included in the Scheduled Castes (SC) category designated in the constitution. The term “Dalit” is preferred by many in that category, while the language of Scheduled Castes was meant to replace the “untouchable” term that was dominant in the British era.

An individual’s caste status has historically been quite determinative of the educational, occupational, and economic opportunities available to them. Although there have been exceptions, such as B.R. Ambedkar, who authored the constitution and was also a Dalit activist, Dalits especially were often denied access to the full range of opportunities open to those with a higher caste status. In the late 1970s, the Mandal Commission made recommendations to help increase opportunities for those of lower castes. However, these recommendations were themselves controversial and were not really implemented until beginning in the 1990s.

Over time, there have been other groupings based on caste. The Brahmins, Kshatriyas, and Vaishyas are classified as General Category, or Forward, Castes. “Lower caste” is made up of other caste categories. The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes identified in the Indian constitution are different from the Other Backwards Classes (OBC) category, which emerged in the 1990s in reference to other lower caste groups in Indian society who were socioeconomically and educationally disadvantaged but did not fall into the more strictly classified Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. Educational and occupational reservations have also been made for people in the Other Backwards Castes. Over two-thirds of Indians identify themselves as belonging to lower caste categories, roughly split between the Scheduled Tribes and Scheduled Castes on one hand and the Other Backwards Classes or Most Backward Classes; only four percent of the population identifies as Brahmin (Pew Research Center 2021).

2.5. Ethnic, Religious, and Cultural Conflict

As noted in Section 2.3, India’s two largest, and most conflict-prone, religious groups are Hindus and Muslims. Tensions between these two groups pre-date independence, and indeed was the primary cause of the Partition that divided British India into the separate countries of India and Pakistan. However, there have been periods of violence against other religious groups as well. Violence against Muslims and Christians in particular have increased with the BJP’s rise to power and the increase in the prominence of Hindutva ideology.

2.5.1. Hindutva

Hindutva is a right-wing extremist form of Hindu nationalism that advocates for India to be a Hindu (as opposed to secular) state, promoting Hinduism as a state religion and Hindu identity as the “pure” form of Indianness. Hindutva promotes Hinduism at the expense of other religious groups in India, and especially at the expense of Muslims and Christians, who are viewed as “outsiders” to India because of those religion’s origins outside the geographical boundaries of the Indian subcontinent. This marginalization includes limitations on the rights of minority groups and even an increase in violence toward members of these groups.

Hindutva emerged as an ideological movement in the 1920s and drew inspiration from fascism. Hindutva leaders even allied themselves to the fascist leaders of Italy (Benito Mussolini) and Germany (Adolf Hitler) to emphasize their opposition to British colonial rule in the country. More recently, Hindutva has been championed by the Bharatiya Janta Party (BJP) and the leader of the party and current prime minister, Narendra Modi, as well as by a Hindu nationalist paramilitary organization, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). Modi was previously chief minister of the western state of Gujarat, which faced riots led by Hindu groups after a train carrying Hindu religious pilgrims caught fire. Over 1,000 people, overwhelmingly Muslim, were killed, and more than 2,500 people were injured. Modi was determined to not be responsible for the riots, but was heavily criticized for not doing more to stop the violence. Anti-Muslim and anti-Christian violence has increased since the BJP election win in 2014. In 2019, Modi invoked Hindutva ideas during the election campaign, further encouraging tensions between Hindus and other groups in society. As prime minister, Modi frequently visually ties himself to a Hindu identity by wearing colors associated with the religion. In many ways, what Modi is currently doing with Hindu identity is similar to what Gandhi did in the lead-up to independence, when he advocated for an open and explicit Hindu identity.

2.5.2. Anti-Muslim Violence

While the largest outbreak of anti-Muslim violence occurred around Partition, which resulted in a total of 200,000-2,000,000 deaths across religious groups and the displacement of 12-20 million people, other periods of violence have occurred, resulting in roughly 10,000 Muslim deaths since 1950. In general, Muslims have been the target of employment, housing, and education discrimination, and are the most common victims of religious violence. There has also been an uptick in anti-Muslim violence since the BJP and Prime Minister Narendra Modi came to power: hate crimes and hate speech have both increased markedly since 2014, and continue to increase the longer the BJP and Modi have been in power.

One form of anti-Muslim violence in particular has emerged in more recent years. While the cow has been considered sacred by groups within Hinduism for hundreds of years, it has also become a point of importance to the Hindu right. In this context, cow protection mobs have emerged since the early 2010s and have almost exclusively targeted Muslims through riots and lynchings. Muslims are accused of slaughtering and eating cows, especially around the Eid holy days, sparking localized pogroms.

Moreover, the BJP government in Uttar Pradesh has also sought to undertake a census of cows (The Economist 2024), which could facilitate more violence if the number of cows over time is deemed to have changed more than expected by typical birth and death rates among the animals. Those accused of perpetrating violence against Muslims in the name of cow protection have typically faced little punishment (The Economist 2022).

2.5.3. Anti-Sikh Violence

Although the Sikh-majority state of Punjab was especially affected by Partition violence, the relationship between Hindus and Sikhs has been less consistently violent than that between Hindus and Muslims. Nonetheless, there have been period of notable anti-Sikh violence in the country, including during the 1960s-1980s and again after the BJP’s rise to power.

With the reorganization of Indian states around language in 1966, Punjab became the only majority-Sikh state. Punjab’s relationship with broader India was strained, mainly around water rights and the division of the population of the previous territorial configurations from which the states of Punjab and neighboring Haryana emerged; with the creation of the new states, the Sikh population was split between them. This tension came to a head following the assassination of Indira Gandhi by her Sikh bodyguards in 1984. The assassination itself was a response to the Indian government’s assault against a Sikh extremist who had taken refuge in the Golden Temple, the most sacred Sikh shrine. Operation Bluestar was seen as an attack on the broader Sikh community. In response to the assassination, Hindu vigilantes struck back against Sikhs, killing more than 2,100 Sikhs in the Indian capital and more than 600 Sikhs in other parts of the country.

Following this wave of violence, an agreement over aspects of the governance of Punjab was reached with Rajiv Gandhi, and Sikhs were granted fuller control over their internal religious governance. However, resentments over 1984 lingered, with generally higher levels of violence against and by Sikhs from the mid-1980s to the mid-to-late 1990s. Although the movement for an independent Sikh state declined in popularity beginning in the late 1990s, conditions remain conducive for an increase in tensions. And indeed, following the BJP’s rise to power, Sikhs have been accused of being terrorists and secessionists, prompting an uptick in violence against Sikhs, including abroad, as in the 2023 killing of a Sikh activist (and American citizen) in New York City (Singh and Kaur 2023).

2.5.4. Anti-Christian Violence

Like violence against other religious groups in India, one source of tension with Christianity is the fear that Hindus will be coerced into converting to other religions. Laws have been passed to prevent coerced conversion. However, forced conversions are quite rare, and some anti-forced conversion laws come closer to criminalizing even voluntary conversion away from Hinduism (although there has been an increase in forced conversions to Hinduism) (Wilson 2023).

Some anti-Christian violence has targeted missionaries, though most of the violence has targeted Indian Christians. This violence has also increased with the rise of Hindutva ideology and the rise of the BJP and Modi. From 2012, anti-Christian violence has increased more than 400%, especially beginning in 2016 (Sen 2023). In 2016, there were 247 episodes of violence against Christians (Sen 2023). In 2021, there were 505 (Sen 2023). In 2023, there were over 700 and this number increased by more than a third in 2024, when there were more than 830 attacks (Sen 2025).

Section 3: Political Culture and Civil Society

3.1. Religious Organizations

3.1.1. Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS)

Perhaps the most important religious civil society organization in India today is the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a primarily upper-caste Hindu nationalist paramilitary organization that was founded in 1925. The RSS is the lead organization in a broad umbrella of Hindu nationalist organizations, collectively known as the Sangh Parivar, which also includes the BJP. In this role, the RSS, even when less active itself, as provided a basis for other Hindu nationalist groups to mobilize. The RSS espouses the Hindutva ideology. It has been banned four times, including after the assassination of Mohandas Gandhi by one of its members, and the destruction of the mosque in Ayodhya that sparked anti-Muslim riots in 1992. It has been labeled a right-wing extremist organization (Atkins 2004) and has the largest membership of any such organization in the world, somewhere between 2.5 and 6 million members. The RSS participates in a variety of activities, like community outreach, education, youth empowerment, environmental conservation, and cultural preservation, but its Hindu supremacist orientation, and the marginalization of and violence toward minority groups that accompanies Hindu supremacy, has kept it a controversial organization.

3.2.2 Non-Hindu Faith-Based Organizations

Other religious organizations, like those affiliated with Christianity and Islam, have often been established to minister to the needs of India’s minority populations, including Dalits. Perhaps the most famous of these is the Missionaries of Charity in Kolkata (formerly Calcutta), founded by Mother Teresa and serving the poorest members of the community. Such organizations have also been the subject of controversy, accused by Hindu nationalist organizations of converting the poor and vulnerable away from Hinduism. Non-Hindu faith-based organizations have also found themselves facing restrictions after the implementation of amendments to the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA) in 2020 (Pattnaik and Sahoo 2022), discussed in more detail in Section 3.5.

3.2. Feminist/Women’s Movements

Modern women’s movements emerged during the colonial era, in the late 1800s, focused on issues like education and economic empowerment. This era also saw the emergence of communication about social reform between women across the country, rather than primarily within families or local communities, and doing so in forums like publications in both English and vernacular languages (Jaiswal 2018-2019). Many of the first women’s organizations were founded by men, though national organizations formed by women emerged after World War I, including the All-India Women’s Conference, the Women’s Indian Association, and the National Council of Women in India. These newer organizations focused on issues like child marriage and women workers’ rights. Women were also active in the independence movement and accompanying civil disobedience campaign.

The second wave of the feminist movement in India began in the 1970s (Nielsen and Waldrop 2014) with a focus on sexual and domestic violence against women, including dowry and honor-based violence, in which male relatives inflict harm on women perceived as causing damage to the family reputation through their presumed sexual activity. During this period, there were concerns that the preferences and activities of higher-caste and/or economically middle-class women would overshadow and marginalize those of lower-caste and working-class women. There were a wide range in the types of groups that emerged at this time, from organizations with ties to specific political parties, groups independent of these political parties but operating at relatively high levels, and grassroots organizations in local settings. Organizations also took on issues regarding gender discrimination outside of violence.

Issues of violence remain at the forefront of the women’s movements today, drawing increased awareness from high-profile cases of gang rape (Arya 2022). The prominence of concern over violence against women is underscored by attitudes in broader Indian society, where nearly 75% of adults see violence against women as a “very big problem” (Pew Research Center 2022). However, economic mobilization never went away completely, and the All-India Democratic Women’s Association, the founded in 1980 in a merger between multiple rural and working-class women’s organizations, is the largest women’s group in the country in terms of number of members, geographic scope, and ability to adapt to emerging issues (Tricontinental 2021).

3.3. LGBTQ+ Movements

A discernible push for LGBTQ+ rights in India has been much more recent than the women’s movement, only really emerging in the late 1970s with the first systematic research on homosexuality in India (Yadav 2021). The movement has also been centered on “grassroots lobbying and aggressive litigation” in “one of the world’s most effective movements for rights for LGBTQ people (Schultz and Naqvi 2023). In the early 1980s, the first All-India Hijra Conference was held, with over 50,000 attendees, and Hijras were legally recognized as a third sex in 1994, which also granted them voting rights (which had previously been administered on the basis of nondiscrimination by sex, defined as male and female). The Indian Supreme Court subsequently ruled in 2014 that transgender people fall into the Hijra category, and the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act of 2019 prohibits discrimination against transgender individuals, including in employment, education, and welfare programs.

In 2017, the Supreme Court ruled that an individual’s sexual orientation falls under the Right to Privacy law, giving LGBTQ+ people the opportunity to be open about their identities. In 2018, the Supreme Court struck down a law criminalizing consensual homosexual acts. However, in October 2023, the Supreme Court issued a ruling declaring that same-sex marriage is not a fundamental right, thereby ruling against its legalization. Around the time of the decision, however, 53% of Indian adults supported same-sex marriage (Gubbala and Miner 2023).

3.4. The Media

With the exception of the period of The Emergency and again more recently under Modi, India has traditionally had an extremely robust media landscape. Newspapers were an especially prominent form of media prior to the notable increases in development in the country. Newspapers existed representing the full gamut of diversity in society, with newspapers published in the vernacular languages, Hindi, English, from across the ideological spectrum, and sometimes serving as the mouthpiece for specific political parties. When rates of illiteracy were much higher, there were also individuals who served as news readers to share information with the portion of the population who could not read so that they could stay politically aware and engaged.

3.5. Civil Society Restrictions

In 2009, there were more than 3 million nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) registered in the country (International Center for Not-for-Profit Law 2025). However, especially after the 2019 elections, the Indian government has placed more restrictions on such groups, making it harder for them to operate, especially in the case of groups focused on human rights, as well as non-Hindu religious organizations (International Center for Not-for-Profit Law 2025; Purohit 2022).

Most notably, in 2020, the government placed increased limits on the ability of NGOs to receive funding from international donors. Using the amended FCRA, 6,000 NGOs had their permits for international donations revoked in January 2022; using previous versions of the law and other tactics, more than 20,000 NGOs have lost their ability to receive foreign donations since 2011 (Purohit 2022). The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights expressed concern about the FCRA after it was amended in 2020, fearing that it would become weaponized against particular types of NGOs (United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights 2020).

Section 4: Political Participation

4.1. Voter Participation

India has a history of robust voter turnout rates, often between three-fifths and two-thirds of the electorate. In 2014 and 2019, voter turnout was between 66 and 67 percent. In some states, though, turnout has been much higher. For instance, turnout was 76.2% in Madhya Pradesh’s 2023 state assembly elections, and West Bengal has over 80% turnout in its 2019 state elections (NDTV n.d.).

4.2. Electoral System for the Lower House

Members of India’s lower house, the Lok Sabha, are elected using the first past the post (FPTP) rule in single-member districts. FPTP means that the candidate with the most votes wins, even if that vote total constitutes only a plurality, rather than a majority.

4.3. Electoral System for the Upper House

Most members (238) of the upper house of India’s parliament, the Rajya Sabha, are elected by state legislators through the single transferable vote. The remaining 12 members of the chamber are appointed by the president on the basis of their contributions to Indian society.

4.4. National Political Parties

Although there are two political parties that attract the most attention at the national level, in addition to the more strictly regional parties covered in section 4.5, there have also been a number of smaller, ideological parties, especially on the left. India has hosted a range of communist and socialist parties, although they have tended to play only a marginal role in recent elections. Parties have also existed focused on particular livelihoods, such as farmers/agriculturalists.

4.4.1. Bharatiya Janata Party (240 seats in 2024)

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) emerged in 1980 from another party, the Bharatiya Jana Sangh (BJS), which was itself a political arm of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) Hindu nationalist paramilitary organization. The BJS had joined an anti-Congress coalition after the declaration of The Emergency, but that coalition broke down, and the BJP splintered off. Atal Bihari Vajpayee became the first BJP prime minister in 1996, but his government lasted less than two weeks before breaking down. Vajpayee and the BJP returned to power in 1998, serving as prime minister until 2004. Current prime minister Narendra Modi was a member of both the RSS and the BJS before joining the BJP and served as the chief minister of Gujarat for more than 10 years before becoming prime minister.

4.4.2. Indian National Congress (99 seats in 2024)

The Indian National Congress was founded in 1885, during the British Raj. As discussed in Section 1.7, Congress was the most powerful party in India for the first several decades after independence, never relinquishing control of the Lok Sabha for long, although its electoral support faced a general erosion over that time. That changed in 2014, when the BJP began its decade plus of continuous control. Despite Congress’s general decline in popularity, it remains the second-most popular party in the country by far, and the other party that competes at a truly national level, rather than being primarily concentrated at the state level. In the 2014 election, Congress became the lead party in the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (INDIA), along with 25 other parties. The Congress party won 99 seats in the election, a far cry from their previous electoral successes.

4.5. Major Regional Political Parties (won 10+ seats in 2024 Lok Sabha election)

Because of India’s regional diversity and complexity, not everything that is locally or regionally important will gain traction at the national level. Moreover, because seats are allocated based on population size, it is the large parties in the largest states that have the most opportunity to gain national representation and amplify those regional concerns.

4.5.1. Samajwadi Party (37 seats in 2024)

The Samajwadi Party (SP) was founded in 1992 and adheres to a socialist platform. It is most active and successful in the state of Uttar Pradesh but operates in other parts of India as well, including West Bengal, Maharashtra, and Gujarat. Some of its strongest supporters are people in OBC, as well as Muslims. The SP has allied with other parties at times to help enhance its legislative power, including the INDIA alliance in the 2024 general election. The 37 seats it won in that election made it the third-largest party in the Lok Sabha, behind the BJP and Congress.

4.5.2. All India Trinamool Congress (29 seats in 2024)

The All India Trinamool Congress (TMC) broke with the Congress and was founded in 1998. It held relatively steady with its 2019 performance, remaining the fourth-largest party in the Lok Sabha. The TMC’s stronghold is in West Bengal in eastern India, though it has also won state legislative assembly seats in Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Goa, Manipur, Meghalaya, and Tripura, often through defection by politicians in the India National Congress. Despite its previous break with Congress, it joined the INDIA alliance in opposing the BJP in the 2024 election.

4.5.3. Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (22 seats in 2024)

Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) was founded in 1949. It had some of the earliest representation by the lower castes and took an early stance against the imposition of Hindi as the only official language of India. After the 2019 election, the DMK was the third-largest party in the Lok Sabha; in 2024, it declined to the fifth-largest party. The DMK, like the SP, is in alliance with the Congress. The TMC’s primary areas of influence are in India’s far south, especially the state of Tamil Nadu.

4.5.4. Telugu Desam Party (16 seats in 2024)

The Telugu Desam Party (TDP) was founded in 1982 and has positioned itself as a party focused on supporting the Telugu ethnolinguistic group, and is most active in the Telugu strongholds of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. The TDP allied itself with the BJP beginning in 1998, and continued to do so through the 2024 election, lending important support to the formation of the Modi government.

4.5.5 Janata Dal (United) (12 seats in 2024)

The Janata Dal (United) (JD(U)), was created in 2003 with the merging of the Samata Party, the Lok Shakti Party, and a faction of the Janata Dal. Its policies are social-democratic and secularist. It is most powerful in eastern and northeastern India, particularly Bihar, Manipur, and Arunachal Pradesh. The JD(U) has had a rocky relationship with the BJP and its alliance. It joined the BJP alliance in 2005, left in 2014 in opposition to the prominence of Modi, rejoined it in 2017, left again in 2022, and re-joined the BJP alliance in the 2024 general election, playing an important part in Modi being able to form a government.

4.6 Interest Groups

India has a long history of interest group formation and activity, but few studies have been conducted on the broader interest group environment and universe in the country (Patel 2022). Key areas of organization have been around agriculture, religion, student’s issues, and the environment.

Student groups have played an especially important role, providing a training ground for futures in politics. They have been most prominent and important on the major campuses throughout India, and like other aspects of Indian society, like newspapers, have aligned with the ideologies of the major parties. Indeed, the biggest parties have student and youth wings to encourage mobilization.

Because of the federal organization of the Indian government, in addition to the organizations that operate at the national level, there is much more diversity and numerical representation of interests at the state level.

Voter Participation

India has a history of robust voter turnout rates, often between three-fifths and two-thirds of the electorate. In 2014 and 2019, voter turnout was between 66 and 67 percent. In some states, though, turnout has been much higher. For instance, turnout was 76.2% in Madhya Pradesh’s 2023 state assembly elections, and West Bengal has over 80% turnout in its 2019 state elections (NDTV n.d.).

4.2. Electoral System for the Lower House

Members of India’s lower house, the Lok Sabha, are elected using the first past the post (FPTP) rule in single-member districts. FPTP means that the candidate with the most votes wins, even if that vote total constitutes only a plurality, rather than a majority.

4.3. Electoral System for the Upper House

Most members (238) of the upper house of India’s parliament, the Rajya Sabha, are elected by state legislators through the single transferable vote. The remaining 12 members of the chamber are appointed by the president on the basis of their contributions to Indian society.

4.4. National Political Parties

Although there are two political parties that attract the most attention at the national level, in addition to the more strictly regional parties covered in section 4.5, there have also been a number of smaller, ideological parties, especially on the left. India has hosted a range of communist and socialist parties, although they have tended to play only a marginal role in recent elections. Parties have also existed focused on particular livelihoods, such as farmers/agriculturalists.

4.4.1. Bharatiya Janata Party (240 seats in 2024)

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) emerged in 1980 from another party, the Bharatiya Jana Sangh (BJS), which was itself a political arm of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) Hindu nationalist paramilitary organization. The BJS had joined an anti-Congress coalition after the declaration of The Emergency, but that coalition broke down, and the BJP splintered off. Atal Bihari Vajpayee became the first BJP prime minister in 1996, but his government lasted less than two weeks before breaking down. Vajpayee and the BJP returned to power in 1998, serving as prime minister until 2004. Current prime minister Narendra Modi was a member of both the RSS and the BJS before joining the BJP and served as the chief minister of Gujarat for more than 10 years before becoming prime minister.

4.4.2. Indian National Congress (99 seats in 2024)

The Indian National Congress was founded in 1885, during the British Raj. As discussed in Section 1.7, Congress was the most powerful party in India for the first several decades after independence, never relinquishing control of the Lok Sabha for long, although its electoral support faced a general erosion over that time. That changed in 2014, when the BJP began its decade plus of continuous control. Despite Congress’s general decline in popularity, it remains the second-most popular party in the country by far, and the other party that competes at a truly national level, rather than being primarily concentrated at the state level. In the 2014 election, Congress became the lead party in the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (INDIA), along with 25 other parties. The Congress party won 99 seats in the election, a far cry from their previous electoral successes.

4.5. Major Regional Political Parties (won 10+ seats in 2024 Lok Sabha election)

Because of India’s regional diversity and complexity, not everything that is locally or regionally important will gain traction at the national level. Moreover, because seats are allocated based on population size, it is the large parties in the largest states that have the most opportunity to gain national representation and amplify those regional concerns.

4.5.1. Samajwadi Party (37 seats in 2024)

The Samajwadi Party (SP) was founded in 1992 and adheres to a socialist platform. It is most active and successful in the state of Uttar Pradesh but operates in other parts of India as well, including West Bengal, Maharashtra, and Gujarat. Some of its strongest supporters are people in OBC, as well as Muslims. The SP has allied with other parties at times to help enhance its legislative power, including the INDIA alliance in the 2024 general election. The 37 seats it won in that election made it the third-largest party in the Lok Sabha, behind the BJP and Congress.

4.5.2. All India Trinamool Congress (29 seats in 2024)

The All India Trinamool Congress (TMC) broke with the Congress and was founded in 1998. It held relatively steady with its 2019 performance, remaining the fourth-largest party in the Lok Sabha. The TMC’s stronghold is in West Bengal in eastern India, though it has also won state legislative assembly seats in Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Goa, Manipur, Meghalaya, and Tripura, often through defection by politicians in the India National Congress. Despite its previous break with Congress, it joined the INDIA alliance in opposing the BJP in the 2024 election.

4.5.3. Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (22 seats in 2024)

Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) was founded in 1949. It had some of the earliest representation by the lower castes and took an early stance against the imposition of Hindi as the only official language of India. After the 2019 election, the DMK was the third-largest party in the Lok Sabha; in 2024, it declined to the fifth-largest party. The DMK, like the SP, is in alliance with the Congress. The TMC’s primary areas of influence are in India’s far south, especially the state of Tamil Nadu.

4.5.4. Telugu Desam Party (16 seats in 2024)

The Telugu Desam Party (TDP) was founded in 1982 and has positioned itself as a party focused on supporting the Telugu ethnolinguistic group, and is most active in the Telugu strongholds of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. The TDP allied itself with the BJP beginning in 1998, and continued to do so through the 2024 election, lending important support to the formation of the Modi government.

4.5.5 Janata Dal (United) (12 seats in 2024)

The Janata Dal (United) (JD(U)), was created in 2003 with the merging of the Samata Party, the Lok Shakti Party, and a faction of the Janata Dal. Its policies are social-democratic and secularist. It is most powerful in eastern and northeastern India, particularly Bihar, Manipur, and Arunachal Pradesh. The JD(U) has had a rocky relationship with the BJP and its alliance. It joined the BJP alliance in 2005, left in 2014 in opposition to the prominence of Modi, rejoined it in 2017, left again in 2022, and re-joined the BJP alliance in the 2024 general election, playing an important part in Modi being able to form a government.

4.6 Interest Groups

India has a long history of interest group formation and activity, but few studies have been conducted on the broader interest group environment and universe in the country (Patel 2022). Key areas of organization have been around agriculture, religion, student’s issues, and the environment.

Student groups have played an especially important role, providing a training ground for futures in politics. They have been most prominent and important on the major campuses throughout India, and like other aspects of Indian society, like newspapers, have aligned with the ideologies of the major parties. Indeed, the biggest parties have student and youth wings to encourage mobilization.

Because of the federal organization of the Indian government, in addition to the organizations that operate at the national level, there is much more diversity and numerical representation of interests at the state level.

Section 5: Formal Political Institutions

5.1. Overview of Governmental System

India is a federal parliamentary system. The parliament is comprised of two houses – the Rajya Sabha (upper house) and the Lok Sabha (lower house). The head of state is a president that is chosen by the two houses of parliament, and the head of government is a prime minister, chosen by a majority of the Lok Sabha, the lower house of parliament.

5.2. Constitution

India’s first constitution after independence was ratified on November 26, 1949, and entered into effect on January 26, 1950. Prior to the constitution, India was governed by the British Government of India Act of 1935. The Indian Constitution is the longest in the world for an independent country, made up of 470 articles. It has been amended over 100 times since its original adopting, proving it to be a dynamic document that changes alongside changing political conditions in the country. It is therefore broad in scope, giving substantial protection to a number of provisions that might be governed through regular legislation in other countries. The sheer numbers of amendments and revisions shows that it has been a flexible and responsive document, unlike some other constitutions that tend to be more rigid and fixed (like the US Constitution).

India is a secular state, meaning that there is no state mandated religion in the constitution. This has proved controversial at times, especially in the current period of rising Hindu nationalism and Hindu nationalist empowerment.

The constitution lays out the various parts of government and the qualifications of holding office. It designates the distribution of power between the national level government and the states, and within each level of government.

The independent Indian state was organized around development-centered social change, and viewed as a nation-building project, encapsulating not just what India already was, but what the leaders hoped India could be. Part of this was the belief that economic development held the key to making social reforms possible. This is part of why India was established as a socialist state, geared toward economic protections for the poorest citizens. Without a population healthy and educated enough to participate in the political and economic work of the country, further economic and social advancement would not be possible. This also guided India’s foreign policy of noninterference, choosing to focus on development over ideology during the Cold War, making India open to aid from more quarters of the global North.

Perhaps most notably, the Indian constitution identifies six rights that are deemed fundamental to all people: the right to equality, the right to freedom, the right against exploitation, the right to freedom of religion, cultural and educational rights, and the right to constitutional remedies. The right to equality enshrines both legal equality and pushes toward social equality. It is from the notion of social equality that the abolishment of untouchability and special protections for women, children, and Scheduled Castes and Tribes.

5.3 Federal Structure

India is made up of 28 states and eight union territories, with boundaries coinciding with language usage. Each state or union territory is further divided into administrative districts, which are comprised of cities, towns, and villages, providing a rich web of governance, though the degree of autonomy becomes more constrained the further down the hierarchy an entity is. That is, the states have less power than the national government, and local governments have less authority than state governments. Many of these subdivisions are more bureaucratic and administrative than political. For instance, administrative districts, may, but not do not necessarily, constitute parliamentary districts.

5.4. Executive – Prime Minister and President

5.4.1. Prime Minister

The prime minister serves as head of government, holding most of the executive power in the country when compared to the president. To hold office, the prime minister must be a citizen and be (or become within six months) a member of either house of parliament. The prime minister assists the president in carrying out a number of their functions. Most prominently, the prime minister serves as the leader of parliament. This involves overseeing the chambers and the proposal and passing of legislation. The prime minister appoints a number of positions, such as the chief election commissioner as well as other members of that body (see below for more about the election commission). Although not tasked with as many formal or ceremonial powers in the constitution, the prime minister is the real bearer of power in the country.

Table 5.1. List of Indian Prime Ministers

|

Name |

Length in Office |

Party |

|

Jawaharlal Nehru |

August 15, 1947-May 27, 1964 |

Indian National Congress |

|

Gulzarilal Nanda (Acting) |

May 27, 1964-June 9, 1964 |

Indian National Congress |

|

Lal Bahadur Shastri |

June 9, 1964-January 11, 1966 |

Indian National Congress |

|

Gulzarilal Nanda (Acting) |

January 11, 1966-January 24, 1966 |

Indian National Congress |

|

Indira Gandhi |

January 24, 1966-March 24, 1977 |

Indian National Congress, Indian National Congress(R) |

|

Morarji Desai |

March 24, 1977-July 28, 1979 |

Janata Party |

|

Charan Singh |

July 28, 1979-January 14, 1980 |

Janata Party (Secular) |

|

Indira Gandhi |

January 14, 1980-October 31, 1984 |

Indian National Congress(I) |

|

Rajiv Gandhi |

October 31, 1984-December 2, 1989 |

Indian National Congress (I) |

|

Vishwanath Pratap Singh |

December 2, 1989-November 10, 1990 |

Janata Dal |

|

Chandra Shekhar |

November 10, 1990-June 21, 1991 |

Samajwadi Janata Party (Rashtriya) |

|

P.V. Narasimha Rao |

June 21, 1991-May 16, 1996 |

Indian National Congress(I) |

|

Atal Bihari Vajpayee |

May 16, 1996-June 1, 1996 |

Bharatiya Janata Party |

|

H.D. Deve Gowda |

June 1, 1996-April 21, 1997 |

Janata Dal (United Front) |

|

Inder Kumar Gujral |

April 21, 1997-March 19, 1998 |

Janata Dal (United Front) |

|

Atal Bihari Vajpayee |

March 19, 1998-May 22, 2004 |

Bharatiya Janata Party (National Democratic Alliance) |

|

Manmohan Singh |

May 22, 2004-May 26, 2014 |

Indian National Congress (United Progressive Alliance) |

|

Narendra Modi |

May 26, 2014-present |

Bharatiya Janata Party (National Democratic Alliance) |

5.4.2. President

As head of state, presidents hold many ceremonial powers, but very few governing powers separate from the influence of the prime minister. Presidents must be citizens of India, at least 35 years old, and qualified to be elected to the lower house of parliament, although they are not a member of either house of parliament.

The president is elected by an electoral college, which is made up of members of the Lok Sabha and the Rajya Sabha, as well as the elected members of the legislative assemblies of the states and union territories. The number of electoral votes is based on state populations. The presidential election uses proportional representation in the form of the single transferable vote, which operates similarly to the alternative vote/ranked-choice voting. The president serves a five-year term, unless they are removed from office through an impeachment process. The president can be re-elected. The vice president is chosen through the same process.

The president has a number of formal powers, including nominating twelve members of the Rajya Sabha, dissolving the Lok Sabha to trigger new elections, and formally approving bills in order for them to become law (but following the actions and recommendations of the prime minister). The president also proposes the annual budget and has nominal appointment power for a number of positions, and the ability to declare national, state, and financial emergencies, though again, most often based on the advice of the prime minister.

Table 5.2. List of Indian Presidents

|

Name |

Length in Office |

Party |

|

Rajendra Prasad |

January 26, 1950- May 13, 1962 |

Indian National Congress |

|

Sarvepalli Radharkrishnan |

May 13, 1962-May 13, 1967 |

Independent |

|

Zakir Husain |

May 13, 1967-May 3, 1969 |

Independent |

|

V.V. Giri (Acting) |

May 3, 1969-July 20, 1969 |

Independent |

|

Mohammd Hidayatulah (Acting) |

July 20, 1969-August 24, 1969 |

Independent |

|

V.V. Giri |

August 24, 1969-August 24, 1974 |

Independent |

|

Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed |

August 24, 1974-February 11, 1977 |

Indian National Congress |

|

B.D. Jatti (Acting) |

February 11, 1977-July 25, 1977 |

Indian National Congress |

|

Neelam Sanjiva Reddy |

July 25, 1977-July 25, 1982 |

Janata Party |

|

Zail Singh |

July 25, 1982-July 25, 1987 |

Indian National Congress |

|

Ramaswamy Venkataraman |

July 25, 1987-July 25, 1992 |

Indian National Congress |

|

Shankar Dayal Sharma |

July 25, 1992-July 25, 1997 |

Indian National Congress |

|

K.R. Narayanan |

July 25, 1997-July 25, 2002 |

Indian National Congress |

|

A.P.J. Abdul Kalam |

July 25, 2002-July 25, 2007 |

Independent |

|

Pratibha Patil |

July 25, 2007-July 25, 2012 |

Indian National Congress |

|

Pranab Mukherjee |

July 25, 2012-July 25, 2017 |

Indian National Congress |

|

Ram Nath Kovind |

July 25, 2017-July 25, 2022 |

Bharatiya Janata Party |

|

Droupadi Murmu |

July 25, 2022-present |

Bharatiya Janata Party |

5.5. Parliament

5.5.1. Lower House

The lower house of parliament is the Lok Sabha and has 554 members. Almost all seats (552) are elected from state and union territories based on population. Two seats are appointed to represent the Anglo-Indian (British Indian) community. States and union territories are divided into electoral districts, with a single member of parliament representing each district. Members of the Lok Sabha are elected directly by voters for terms of up to five years, depending on when the prime minister calls elections.