6 Greece

John Tures

Dr. John A. Tures is a professor of political science at LaGrange College in LaGrange, Georgia, where he has been teaching since 2001. Born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, his family moved to El Paso, Texas, where he became interested in politics beyond America’s borders. He earned his Bachelor’s Degree in both Communications and Political Science from Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas in 1992. After working for USAA, he went on to attend Marquette University in Milwaukee where he received his Master’s Degree in International Affairs in 1994. Tures enrolled in the doctoral program at Florida State University in Tallahassee, where he earned his Ph.D. in political science in 2000. After teaching a year at the University of Delaware and several years at Evidence-Based Research, Inc. in Washington DC, before coming to LaGrange College. In addition to publishing scholarly journals (https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=3y3BVcEAAAAJ&hl=en&oi=sra), he is also a regular newspaper columnist (https://muckrack.com/john-tures/articles).

In addition to growing up next to Mexico, Tures also had the opportunity to travel the British Isles, Western Europe, and East Europe as the Berlin Wall was crumbling. While at Marquette, he and professors and fellow graduate students led undergraduate students to Russia as the country transitioned to democracy in 1993-1994, and the United Nations in the Summer of 1994. At Florida State University, he was part of a team that participated in a multi-week conference in Ohrid, Macedonia in 1996, and taught comparative politics twice in FSU’s study abroad program in San Jose, Costa Rica. While at LaGrange College, he co-led a group of students throughout Greece, traveling from Thessaloniki to Philippi, Delphi, Monastery of the Holy Trinity, and Athens.

Chapter Outline

Section 2: Ethnic, Religious, and Cultural Identity

Section 3: Political Culture and Civil Society

Section 4: Political Participation

Section 5: Formal Political Institutions

The Importance of the Library, As Well As Getting Out Of It

In the movie “Indiana Jones at the Last Crusade,” the famed archaeologist tells his class “Seventy percent of all archaeology is done in the library…books, reading….” But in the next film “Indiana Jones at the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull,” shortly after racing through a library with his son, bumping into a student, Jones answers his question, and adds “If you want to be a good archaeologist, you gotta get out of the library!”

Jones isn’t simply being contradictory. To be a good archaeologist, you have to do both. That means in addition to reading, studying, and researching, it also helps to travel, visit the landmarks, speak with the people, and immerse yourself in the setting and plot of the place.

The field of comparative politics was created after World War II, in answer to questions of how free people could so willingly embrace totalitarianism. Since political science was such a new field, early comparativists had to rely upon the theories and research practices of established scholars, and one such field was anthropology, linked to archaeology, the study of different cultures.

In analyzing different political cultures, it helps to know their history, their ethnicity, race and religion, their political institutions, parties, groups, organization, rules of participation, civil society, and economy. Much of those lessons will be learned in this text, and further reading you’ll do as a student or even a professor, typically in a library.

But you also have to go beyond the library, the important other 30 percent.

You’ll notice there are a lot of pictures of Greece in this chapter. Many contain students as well, from LaGrange College, as well as one from Agnes Scott College. I could have taken static photos of buildings, monuments and ruins, like the types you see in postcards. But I feel it is important to have the reader see students putting themselves were history was made, and key political debates were decided. In addition to the other sites, I took a few students to a nationalist political rally in Athens, something you can’t experience either from reading a book or article, or even watching a news report about it on television or online.

There are plenty of sites that will tell you about how students today are not reading as much as their earlier counterparts, and are less willing to travel, especially since COVID-19. It is my hope that this chapter on Greece will not only stimulate students to read more and learn more about the subjects covered in this text, which is why I provided online links. I even want them headed to the library for more. But I also hope to encourage students to see ours in these photos, imagining themselves heading there on adventures in the quest to discover more of the truth.

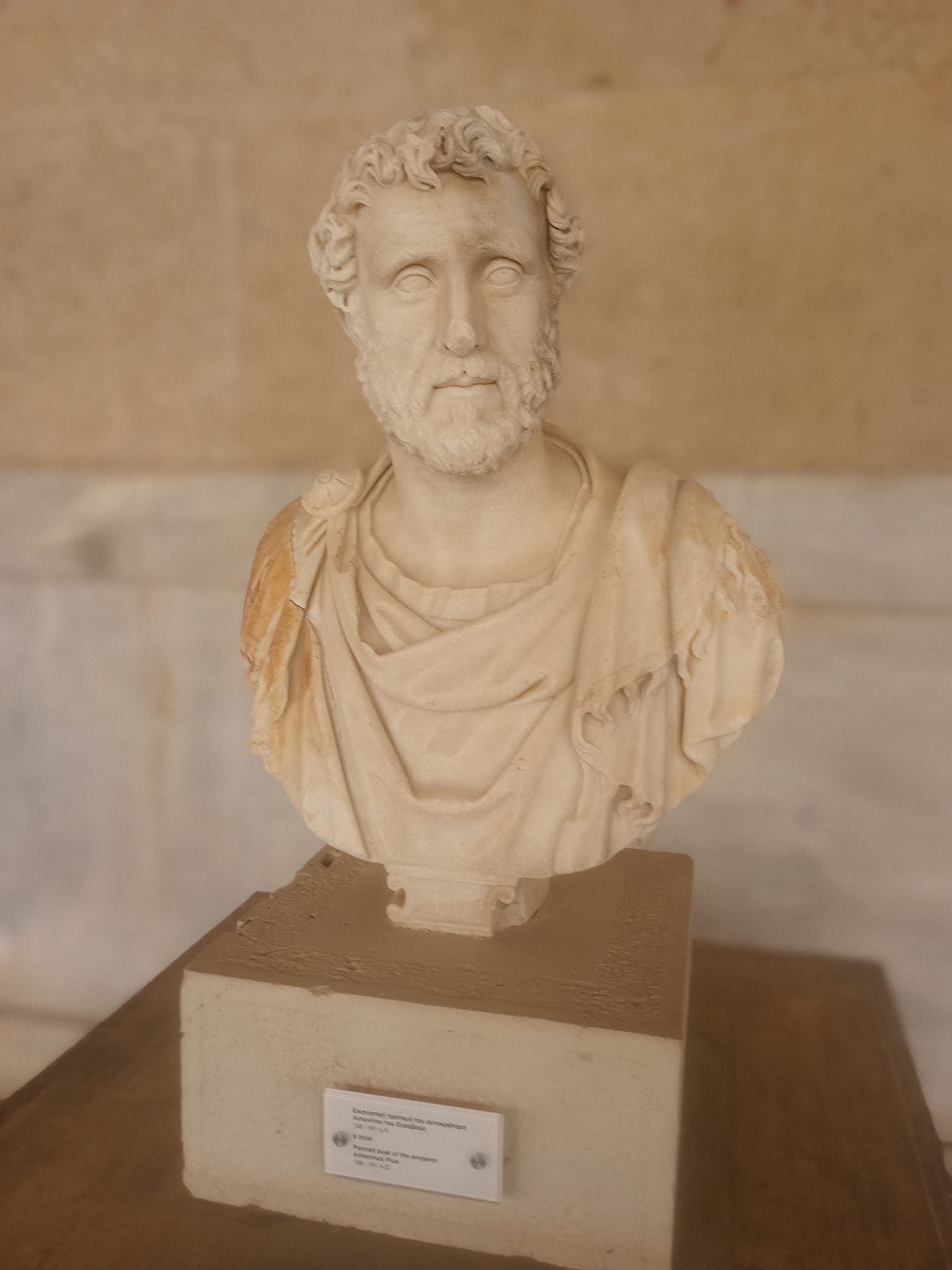

Section 1: History of Greece

The story of historic Greece began with the migration of European peoples from north of contemporary Greece around 1900s B.C. They were ruled by the Minoans of the island of Crete until around 1400 B.C., when the peoples of Greece threw off their control (Encyclopedia Britannica 2024). This new Mycenaean culture, derived from the Minoans, was part of the Bronze Age, until these people were defeated by invaders from the sea around 1150. These new occupants of Greece began to replace the Bronze Age with an Iron Age, when other cultures learned to make steel and more powerful weapons (Encyclopedia Britannica 2024). Scholars are divided about whether the Bronze Age decline was due to natural disasters that destroyed cities and farmlands, or internal unrest from the disruption of trade routes and attacks from nomadic external tribes.

Though the time from late Bronze and early Iron Ages is called “The Dark Ages,” some scholars see this term as misleading. Such people developed alphabets, languages, governance systems, pottery, and industry. This “Continuity Theory” interprets the development of Greek Society as evolutionary, not a series of sharp revolutions from an uncivilized past. Scholar B. C. Dietrich (1970) finds common threads over time for the Greek people, especially on religion. “This century has fortunately abandoned the idea of the Greeks as a unique people who suddenly appeared on Earth, as if from another world, and magically at one stroke produced their singular culture,” he writes. “Nor was Greek religion born in a vacuum but represented the end result of a lengthy development in which the entire Aegean area had a share.” This “Early Iron Age Greece” (EIA) persisted until around 770 B.C. with the formation of the famous Olympic Games, considered a key defining moment of the “Classical” Greek Age (Morris 2008).

In an otherwise disparate confederation of Greek City-States, the Olympic Games cannot be understated as helping a common bond of culture. In addition to these athletic events at Olympia in 776 B.C., there were the “Pythian games at Delphi, the Isthmian games of Corinth and the Nemean games (Swaddling 1988).”

This “Classical” Greek Age, which some characterize this time as starting in 480 B.C. with victories against the Persian Empire, is defined by both tangible creations and intangible contributions. “It was during the Classical Age that the Greeks arrived at some of their great intellectual and cultural achievements,” writes Christopher Brooks (2020). This is defined not by the short-lived and abandoned “democracy” of Athens, but by more enduring contributions. “The fundamental concept of Greek thought, as reflected in drama, literature, and philosophy, was humanism. This was an overarching theme and phenomenon common to all of the most important Greek cultural achievements in literature, religion, drama, history-writing, and art. Humanism is the idea that, first and foremost, humankind is inherently beautiful, capable, and creative,” Brooks (2020) adds.

Many modern students of politics are aware of the association between Greece and democracy. But there were several key differences between these classical and contemporary forms of government. Stanford University Political Science Professor John Ober, also a Classicist, explains. “Unlike the American system of representative democracy, where citizens vote for elected officials to represent their concerns in government, rule in Ancient Greece was direct: Participation was not a choice but a civic duty,” cites Melissa DeWitte (2024). She adds “In a class seminar devoted to deliberation, Ober described how the citizen Assembly made decisions and how those decisions represented the will of the demos, the collective judgment of the people about the best available course of action. The class then discussed some of the tensions that arise when conceptualizing a large, diverse population as a monolithic entity.”

There is a desire to see that ancient form of “people rule” as a more perfect form of government. Yet this system was not without its significant flaws. “But not everyone in ancient Athens was able to participate in political life,” DeWitte (2024) documents. “Excluded from the franchise were women and slaves – not too dissimilar to the limitations America’s Founding Fathers set when they wrote the Declaration of Independence, Constitution, and the Bill of Rights in the late 18th century.” When you exclude someone from “people rule,” is that individual really considered a person in the system?

The classical period was also a scientific revolution. “The importance of Greek scientific work is not primarily in the conclusions that Greek scientists reached, which ended up being factually wrong most of the time,” Brooks (2020) writes. “Instead, its importance is in its spirit of rational inquiry, in the idea that the human mind can discover new things about the world through examination and consideration. The world, thought the Greek scientists, was not some sacred or impenetrable thing that could never be understood; they sought to explain it without recourse to supernatural forces.” An underrated contribution of the Classical Greek Era, influenced by humanism was the development of history. Rather than only chronicle the exploits of the gods, it covered the exploits of the people as key determinants of their destiny. “History as it was first written by the Greeks is not just about listing facts, it is about explaining the human motivations at work in historical events and phenomena,” Brooks (2020) explains. “Likewise, the Greeks were the first to systematically employ the essential historical method of using primary sources written or experienced at the time as the basis of historical research.

That history showed the development of a variety of city-states, from Athens and Sparta to Corinth and Thessaloniki, who would sometimes align themselves when faced with a common external foe, like the mighty Persian Empire (BBC 2023). Victories at Marathon, Salamis and Platea ended the Persian dreams of dominating the Greeks (BBC 2023). Even losses like the heroic struggle against overwhelming odds at Thermopylae only seemed to embolden the plucky Greeks in fighting the powerful Persians from the East.

On the heels of such triumphs, the members of this loose-knit confederation turned on each other, as Athens and its allies battled Sparta and their friends in the highly divisive Peloponnesian War. The surviving Greeks were no match for the Macedonians, an empire to the North. Macedonia conquered much of the Greek Peninsula under Philip II, thanks to innovative military tactics like the phalanx, a tightly-packed rectangular formation of spears and shields involving hundreds of soldiers.

Upon Philip II’s assassination, Alexander the Great introduced “the Hellenistic Era,” which included the unification of Greek culture (he was tutored by the Greek philosopher Aristotle and incorporated scientists into his conquests) into the Macedonian Empire. This powerful force conquered the Persian Empire and the spread their rule throughout the Middle East and into Egypt. Macedonians ruled Greece until their defeat by the Roman Empire in a series of wars from 214 B.C. until about 146 B.C. (Davis 2001, Worthington 2020).

During the Second Macedonian War, Greeks actually joined Romans in fighting against the Macedonians after King Philip of Macedon aligned himself with Hannibal of Carthage. In these battles, the more flexible Roman legion style defeated the phalanx in battles such as Cynocephalia and Pydna (Davis 2001). Much is made of Roman General Flamininus declaring the Greeks were now “free” but they were simply shifted from one empire to another (Worthington 2020).

The Greeks became part of the Eastern Roman Empire, ruled from Constantinople, which is the old Greek city of Byzantium. This political entity ended in 1453, when the Byzantine Empire was toppled by the Ottoman Empire led by Sultan Mehmet II (Charanis 1963). It seemed the Greeks would be never free from being dominated by an external power.

That changed in 1821 when General Alexander Ypsilantis led a revolt in the Danubian Provinces. Unlikely Greek successes continued against the Turks until the rebels formed separate factional governments, enabling the Ottoman Empire to recapture Athens in 1826. International sympathy for the Greeks, coupled with a renewed interest in a renewed interest in Greek culture, led to strong European support for the Greek independence insurgency. Eventually, the Turks conceded Greek autonomy, and eventual independence in the Treaty of Adrianople (Byington. McClelland and Quint 2021).

King Otto I of Bavaria began his rule in 1833 until he was deposed by the Greek National Assembly thirty years later, showing that it was more of a constitutional monarchy, with some checks and balances. That same assembly selected a Danish prince to be the new ruler. King George I served the country from 1863 to 1913, when he was tragically assassinated by an anarchist as he walked the streets of modern-day Thessaloniki in 1913 (New World Encyclopedia n.d.). During his reign, the popular potentate benefited from acquiring new territory at the expense of European wars against the Ottoman Empire, especially Epirus, Macedonia and Northern Aegean Islands in the First Balkan War of 1912 (New World Encyclopedia n.d.) and Western Thrace the Second Balkan War (BBC 2023).

For much of World War I, Greece remained neutral due to infighting, but the country did join the Allies in 1917, and was rewarded with a little territory along the Thracian Coast, land the country lost with the disastrous post-WWI war with Turkey (Petsalis-Diomidis 1978).

Greece recovered some of its military prowess during World War II, when Fascist Italy attacked the country from occupied Albania. In fact, the impressive Greek forces not only repelled Benito Mussolini’s invasion but also took some Albanian land in the counterattack (Blytas 2009). This led Nazi Germany to launch an all-out attack on Greece. Greek fighters eventually succumbed to the combined attack of Germany, Italy, and Bulgaria, and the country was partitioned among all three occupiers, effectively delaying the critical attack by the Nazis on the Soviet Union (Blytas 2009).

Greek partisans continued to wage an insurgency against their oppressors, often suffering terrible reprisals, reminiscent of the American movie “Red Dawn” about resistance to a fictional Soviet takeover of America during the Cold War. Thousands of villages suffered this fate, where the men were shot and the villages burned, costing the country roughly 13 percent of its population. Those who suffered the worst were the Salonika Jews, who were massacred when deported from Northern Greece to Auschwitz-Birkenau, as well as Treblinka, according to the Holocaust Encyclopedia (n.d.), killing 80 percent of the pre-WWII Jewish population.

No sooner had World War II ended than a new conflict emerged in Greece. The country became an early Cold War battleground, as Greek Communists (with support coming over the Albanian, Yugoslav and Bulgarian border) fought the restored Greek Government, backed by the Western powers (Iatrides and Rizopoulos 2000). The communists were divided into two groups: one that supported Yugoslavia Josip Broz Tito and the other preferred Josef Stalin of the Soviet Union. This suffered when Tito and Stalin had a falling out. The Greek Communist murder of civilians, including actress Eleni Papdaki, and attacks upon the Greek Orthodox Church, turned much of the population against them (Lengel 2017). Prisoners of the Greek authorities were subject to brutal conditions and deaths (Lengel 2017). But thanks to American support, with a policy known as The Truman Doctrine, the Greek government was able to eliminate Communist forces, as the survivors fled to Albania (Iatrides and Rizopoulos 2000).

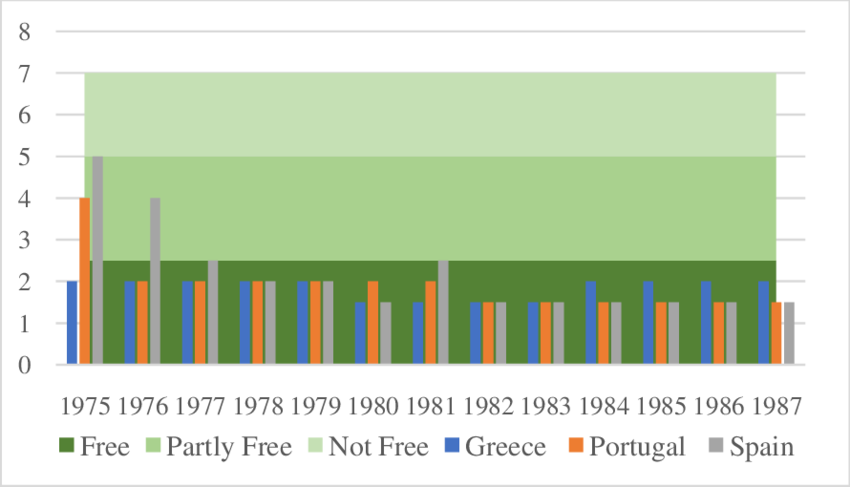

A constitutional monarchy with democracy emerged in Greece afterward the civil war; this system persisted until 1967. Fearful of an electoral victory by Centre Union’s candidate Georgios Papandreou, a former prime minister who was earlier dismissed by young King Constantine II, a group of Greek military colonels overthrew a caretaker government (Kassimeris 2006). They had been eager to prevent the United Democratic Left from joining an alliance with the Centre Union. Right-wing critics claimed the UDL was a front for the Greek Communists, banned since the Greek Civil War. The military junta, led by Colonel George Papadopoulos (appointed prime minister), conducted many arrests, jailings, tortures, and even deaths of those who disagreed with them (Kassimeris 2006). International condemnation led Greece to withdraw from the European Council. An ineffective counter-coup attempt organized by King Constantine II failed (Kassimeris 2006). After a time, Prime Minister Papadopoulos sought to liberalize the country somewhat. Papadopoulos was toppled by a hardliner, Brigadier General Dimitrios Ioannidis, in November of 1973; this new general opposed such reforms (Davison 2010). Ioannidis’ bellicose policies and support for ousting Greek Cypriot moderate Archbishop Makarios III in favor of a right-wing military coup on the island nation, in 1974. Turkey responded by invading Northern Cyprus, a military move that has divided the Cypriot country even today (Davison 2010).

Ioannidis’ policies turned even members of the original junta against him and he was deposed. The old junta members invited a former Prime Minister back to lead a caretaker government until elections could be restored. Ioannidis, Papadopoulos and two other junta leaders were originally sentenced to death, but their penalties were commuted to lengthy prison terms. A referendum rejected the constitutional monarchy by a wide margin, and Greece became a parliamentary republic with some powers given to a president (BBC 2023). Socialist Andreas Papandreou even won the election in 1981, and Greece joined the European Union a decade later (BBC 2023).

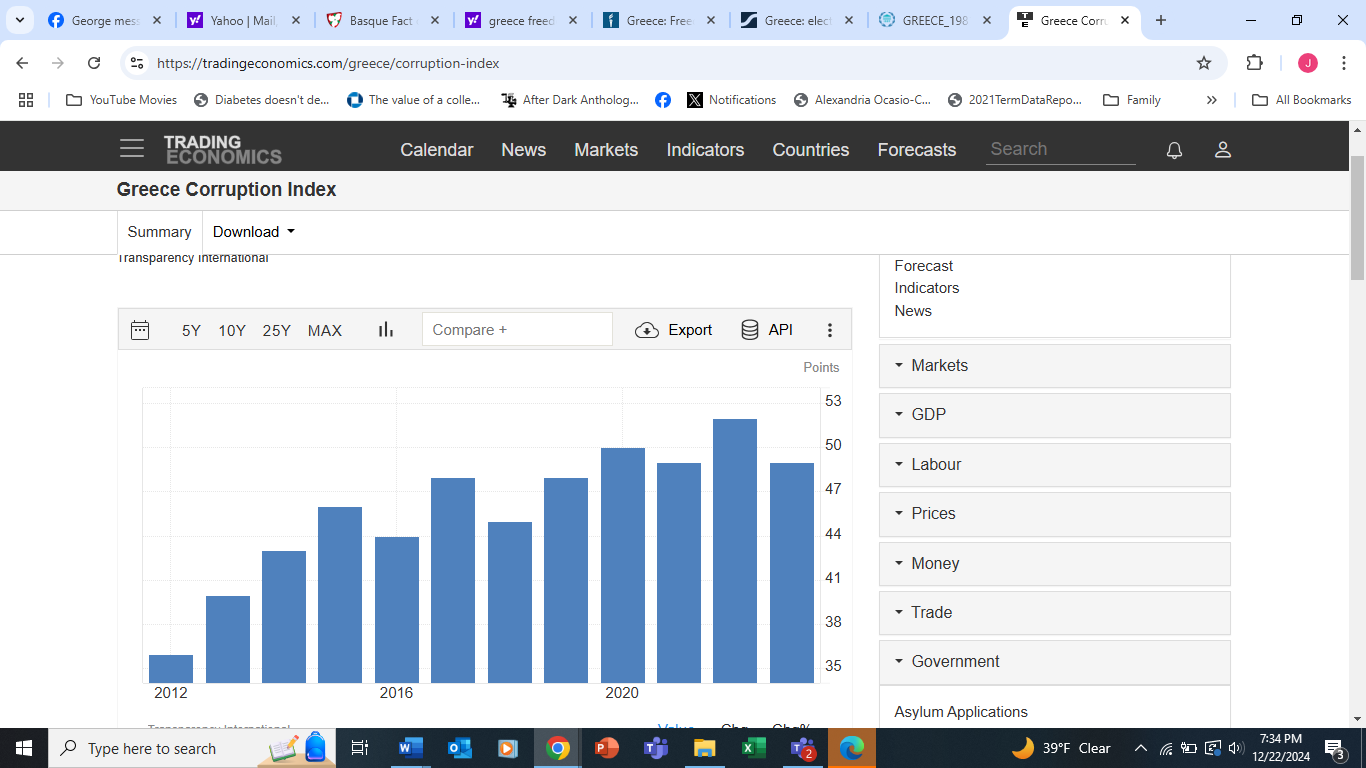

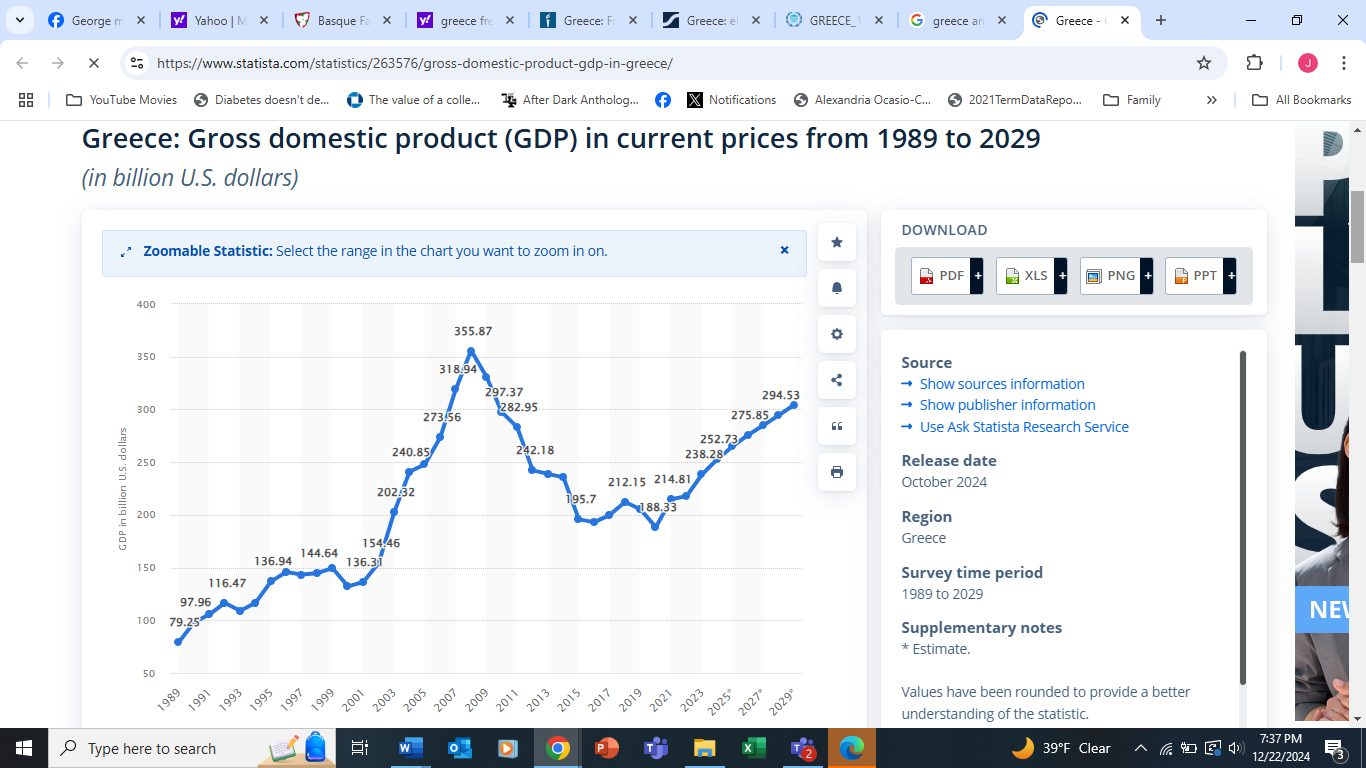

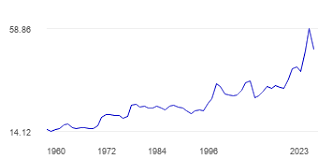

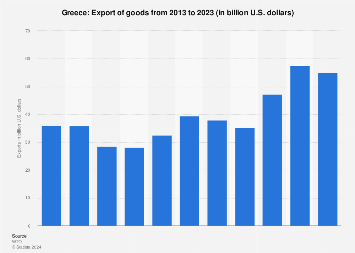

Athens, the original host of the reborn 1896 Olympics, won the right to host the games again in 2004. Though the athletic events put Greece in the international spotlight, spending on the Olympics and other deficit spending led to an economic crisis for Greece during the Great Recession (BBC 2023). International bailouts from the EU worked to avoid a Greek default that could spread to other countries, while the country was forced into economically painful austerity measures (BBC 2023). Though Greek leaders have claimed their country has emerged from the crisis, some see that Greece still has some economic and political vulnerabilities (Barber 2024).

Section 2: Ethnic, Religious and Cultural Identity

2.1 Greek Ethnic Origins

[I]t was as an influx of many different tribes, and probably by slow degrees, that the gifted people whom we call the Greeks came to settle in the lands that were to be their own (Burckhardt 1998).” He acknowledges the difficulty of tracking this ethnohistory due to conflicting stories and legends. “In traditional accounts, early Greek times appear as a succession of migrations; one tribe drives out and supplants another until driven out in turn by a third, and this process may have lasted many hundreds of years. Not until the so-called Dorian migration of the eleventh century did the location and distribution of the Greek people begin to take on its final form (Burckhardt 1998).”

These Dorian invasions from the Northwest territory of Epirus supplanted the Achaeans, original inhabitants of the Peloponnesus and islands such as Crete in the Mycenaean region, expelling them to an enclave on the giant peninsula (The Latin Library n.d.). Ionians made their way to the Attica region, near modern-day Athens. Some speculate that these many invasions were the inspiration for Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. Greeks began a colonizing movement around the time of the first Olympics (776 B.C.), spreading their kin from the Italian Peninsula and Western Europe to Asia Minor (The Latin Library n.d.).

2.2 Significant Ethnic Minorities

While 98% of the population of 10.9 million residents known as the Hellenic Republic in modern Greece identify themselves as Greek, there are minorities within the country. Those include several who identify with a neighboring country, and most likely became minorities when borders changed (Chepkemoi 2019). These include the Albanians (445,000), Macedonians of Slavic descent who number about 150,000. There are also Aromanians who speak a Latin dialect, but consider themselves Greeks (who are roughly 200,000 at a recent count), as well as Arvanites, who were originally Albanian, but took pains to adopt the Greek culture; their number is close to 95,000 at last count (Chepkemoi 2019).

There are also Romani (often pejoratively referred to as “gypsies”) are nomadic people believed to have come originally from India. Their population, split between Roma Orthodox Christians and Roma Muslims, is a little over 200,000 people (Chepkemoi 2019). In Greece, one might find 90,000 people of Turkish ethnicity, but the Greek government considers them Islamic minorities, not Turks (Chepkemoi 2019). Finally, there are Pomaks, Bulgarian Slavs, often Muslim, who adhere to unique customs, and who consist of about 35,000 (Chepkemoi 2019).

2.3 Official Language

As with most things Greek, the language has evolved over time from ancient traditions, but the extensive age makes the origins harder to trace. What is considered a Greek language has existed for almost 5,000 years, traced back to the 14th and 13th Centuries B.C. during the Mycenaean culture (Encyclopedia Britannica n.d.). This was succeeded by a form of the language which many call “Classical Greek” but is also known as Attic or Ionian. With the spread of Greek culture via Alexander the Great, a Hellenistic Greek variation known as Koine exploded (Kuiper n.d.).

Purists rejected this variation and opted for the Attic language. During the Byzantine Empire, Koine returned as the Hellenization of the Eastern Roman Empire occurred. The Ottoman Empire sought to impose a different variation, but Greeks on the Island of Crete, who held out until the mid-1600s, spoke a variation similar to the one from the Byzantine Era (Kuiper n.d.). That version was adopted by Greeks upon independence in the 1820s, which has evolved into what’s now known as standard modern Greek (Kuiper n.d.).

2.4 Dominant Religious Denomination

The Greek Orthodox Church story is intertwined with the story of the Orthodox Christianity in general, given the role Constantine played in Christianizing the Eastern Roman Empire in the year 336 (Papadakis 1996). This religion originally spread from Jesus Christ to the Apostles beginning with the Pentecost when the disciples received the Holy Spirit (Papadakis 1996). Pentecost is therefore a key holiday in Orthodox Christianity, whose history is closely paralleled with the New Testament’s “Acts of the Apostles.” The missionary work of Paul and the other 12 disciples of Jesus throughout the Balkans and Middle East is where many early Orthodox Christian Churches were founded (Papadakis 1996). Its capital was Constantinople, the site of the impressive Hagia Sophia (Papadakis 1996).

The destruction of Constantinople by the Ottoman Empire in 1453 did not destroy Orthodox Christianity. Though some key religious sites in Greece and Turkey were converted to Mosques, the faith was still tolerated throughout the region. The religion even spread to Russia and East Europe, as well as Western Europe and even to North America in 1768.

The Orthodox Church follows the Old and New Testaments and the oral traditions of Christianity (Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America 2023). It emphasizes the importance of four obligatory sacraments: Baptism, Chrismation (Holy Oil), Confession, and Holy Communion, along with three optional ones: Matrimony, Holy Orders (Ordination), and Unction, or the Anointing of the Sick (Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America 2023). Its religious holidays contain some from other Christian traditions, along with some unique ones, as well as the fundamental importance of the Orthodox Funeral (Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America 2023).

2.5 Significant Religious Minorities

According to a 2015 estimate by the CIA World Factbook, the Greek Orthodox Church membership can be as many as 90 percent, or at least 80% of the country, with Muslims making up 2 percent and other religions can be 3-4 percent. Those who identify with no religion may be as few as four percent, and as many as 15 percent of the population (CIA World Factbook 2015).

2.6 Historical Ethnic or Religious Conflict

“[T]he struggle for Greek independence begins in 1453 with the fall of Byzantine Constantinople, spans centuries of subjection and assimilation to Ottoman rule, and culminates in the late 18th century with a cultural Greek enlightenment that draws the attention and support of most of Europe,” writes David Jenkins (2024). Greece independence was later recognized after the decisive 1827 Naval Battle of Navarino, where a Turkish fleet three times larger than the Greek allies’ fleet from Britain, France and Russia lost 70 of 78 ships to superior ship size and cannon power (Abshire 1959).

The evolution from an autonomous Greece to an independent one in 1832 would not quell the country’s hostility toward their former oppressors, coupled with a desire to acquire nearby lands traditionally part of ancient Greece, from Epirus in the Northwest to Thrace in the Northeast. The differences in culture between the Greeks and Turks made this conflict an ethno-religious battle, and not merely one based on political differences or territorial disputes.

Greece won territory from the Ottoman Empire in the First Balkan and Second Balkan Wars, but the Greco-Turkish War from 1919 to 1922 in the wake of World War I was a disastrous setback. The postwar treaty was designed to partition the Ottoman Empire, and enabled Greece to claim the Western Turkish Coastal City of Smyrna (now Izmir) where many ethnic Greeks and Armenians lived. Many stories of Greek atrocities toward Muslims motivated the new Turkish military under Kemal at-a-Turk to repulse the Greek armies. The war delved into brutality by both sides.

After a series of cruel clashes, a new Treaty of Lausanne was signed, forcing up to 1.5 million Greeks to be expelled from Turkey to Greece, and half-a-million Turks to leave Greece for the new Turkish Republic. “The war resulted in the largest compulsory population exchange in history up to that time (2 million people) and helped define the concept of ethnic conflict,” Kinley (2019) wrote.

Not only did the country lose territory to the new country of Turkey, but ethnic Greeks in the Ponthic area of Anatolia were subjected to ethnic cleansing, with the massacred numbering over 350,000 (Lefteris 2020). Indeed, while in Athens, I witnessed an extensive political rally with attendees wearing the black costumes of those Greek people whose settlements could be found along the Black Sea.

“The exchange solidified the idea of both Greece and Turkey as homogenous nation-states,” Kinley (2019) adds. “Although there were still minority communities left out of the exchange, Greece essentially became an Orthodox Christian nation, whereas Turkey became a Muslim Republic. This war and the concept of religious homogeneity still causes tensions between the two countries today.”

Additional clashes between Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots, the latter backed by Turkish paratroopers in 1974, kept ethnic tensions high. In 1996, only some intense negotiations by the United States could keep the Greeks and Turks from fighting over the island of Imia in the Aegean Sea, known as Kardak by the Turks, off the coast of Turkey, despite the two nations being allies of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

In my travels to Turkey, on the anniversary of World War I, I heard more of their side of those on the other side of the Aegean Sea. They expressed their outrage at what they called anti-Turk propaganda from Greece, and emphasized actions done by those abroad to ethnic Turks. It is clear that the bitterness of the prior conflict will keep tensions in the region simmering, and could boil over until a full effort at addressing the killings of the past takes place. It was clear that this conflict is more rooted in hatred for past atrocities than the drawing of the borders or old territorial claims.

The attitude of many Greeks and Turks may well be similar to what I experienced at a University in Prilep, Macedonia. I saw an artwork depicting Macedonian men, women and children, hanging from trees. I was told it was a massacre perpetrated by the Turks during the rule by the Ottoman Empire. I pointed out that during that week, there was a large Macedonian cultural festival, with Turkish dancers featured prominently. “We forgive,” a university official responded. “But we never forget.”

Section 3: Political Culture and Civil Society

3.1: NGO & Civil Society Activity

Ingram (2020) from the Brookings Institute defines civil society as comprising “organizations that are not associated with the government—including schools and universities, advocacy groups, professional associations, churches and cultural institutions (business sometimes is covered by the term civil society and sometimes not).”

Many actors in civil society are nongovernmental organizations or NGOs. Harvard Law School (2022) defines NGOs as “Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) are typically mission-driven advocacy or service organizations in the nonprofit sector….What began as consultancies with selected NGOs has evolved into a system of governmental and intergovernmental partnerships.”

Ingram (2020) sees civil society as the key ingredient for a country’s development. “Civil society organizations play multiple roles,” he writes. “They are an important source of information for both citizens and government. They monitor government policies and actions and hold government accountable. They engage in advocacy and offer alternative policies for government, the private sector, and other institutions. They deliver services, especially to the poor and underserved. They defend citizen rights and work to change and uphold social norms and behaviors.”

When the people mobilized, and united with disaffected elites to bring down the Greek military dictatorship in 1974, civil society and NGOs in the country were considered quite strong. That changed in the 1980s as cynicism and distrust of democratic politicians crept into the mindset of the people (Sotiropoulos 2004). But as Dimitri A. Sotiropoulos observes for The Hellenic Observatory of The European Institute, “First, some formal voluntary associations have been quite strong, and civil society in contemporary Greece is not as uniformly weak as it is generally thought to be. And second, in addition to formal civil society associations, of which there are comparatively fewer in Greece than in other EU countries, there is an informal civil society. This emanates from a flourishing, albeit informal and thus not officially registered, social mobilization which substitutes for the usual, formal civil society found in modern Western societies.”

But just as formal Greek political institutions were challenged by cynicism 40 years ago, contemporary civil society and NGOs face pressure on three fronts: (1) the economy, (2) immigration, and (3) the environment.

The financial crisis in Greece not only assaulted the economy of Greece, but also assailed its formal political institutions. This gave the opportunity for the country’s non-governmental organizations to step in and fill the void.

Tzifakis, Petropoulos and Huliaras (2017) contend “A number of empirical studies have shown that a financial crisis can inflict a serious damage on the nonprofit sector—mainly through a sharp decline in revenues. However, the Greek case shows that a crisis can also have some positive effects on NGOs: many nonprofits introduced reforms that increased efficiency, the number of volunteers reached record levels, and there was a spectacular rise in funding by private philanthropic foundations.” The authors contend that this can create dependency issues, as such groups are less likely to be citizen-led, or citizen-directed.

In Greece, NGOs and civil society seeking economic reform need help from the European Union. The Global Call to Action Against Poverty (n.d.) reports “The Hellenic Platform for Development, an umbrella-organization that operates as a ‘national platform,’ leads a network of Greek Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) active in the fields of sustainable development education, humanitarian aid, global citizenship action and developmental social support. Its current members are supported by a large segment of the Greek society and offer their programs nationwide as well as in many developing countries.” But the E.U. often has its other issues to contend with, from challenges coming from member states, and external threats from Russia.

Just as the economic crises hit Greece suddenly, so too did the immigration crisis of 2015, as hundreds of desperate migrants from the Middle East began arriving on the Dodecanese Islands in the Aegean Sea, fleeing war and economic poverty. “In 2015, about 500,000 asylum seekers entered the EU through that island alone. This represents about half the overall sea arrivals in the EU,” report Skleparis and Armakolas (2016).

According to Skleparis and Armakolas (2016). “Greece was unprepared and unable to handle this massive wave of migrants. “The political and financial constraints after five years of austerity measures had severely limited the Greek state’s ability to react effectively and on time. Moreover, the new Greek government elected in January 2015 underestimated the severity of the humanitarian crisis and failed to prepare an adequate response despite the clear signs that 2015 would become a year of mass irregular movement of people into the EU. Furthermore, for a month prior to the September 20, 2015, national elections – a key period in terms of the developing situation on the islands – a caretaker government was in place, which was unable to initiate an emergency response.”

Moreover, international NGOs faced their own inability to solve the migration problem. Skleparis and Armakolas (2016) add “International NGOs were also slow to realize that Greece was in need of humanitarian assistance, mainly due to the location of the humanitarian crisis. They assumed that an EU Member State such as Greece would be able to respond on its own. Most international NGOs were not formally registered in Greece, which led to delays in their mobilization. When these organizations arrived on the ground, they faced severe bureaucratic obstacles, such as tight employment and visa regulations, which prevented them from deploying, experienced aid workers. Financial (capital) controls in Greece also hampered their ability initially to mobilize resources. Finally, major Greek NGOs were also slow to respond to the humanitarian crisis, mainly due to their commitments to ongoing aid programs in mainland Greece. Supporting Greek nationals affected by the economic crisis limited their capacity, both in terms of funding and staff, to scale up their operations on the islands.”

The environment represents another sector where NGOs have sought to solve problems, only to face challenges from the economic crisis of 2008. An early ENGO (environmental NGO), the Hellenic Society for the Protection of Nature began as early as the 1950s, while the movement joined the global awareness and desire for change in the 1970s, coinciding with the return of democracy. Botetzagias and Koutiva (2015) report that due to a slow drying up of funds from businesses, foundations, businesses and the state, such ENGOs are under greater pressure to seek funds from individual members. And in times of economic hardship, donations to environmental groups suffer.

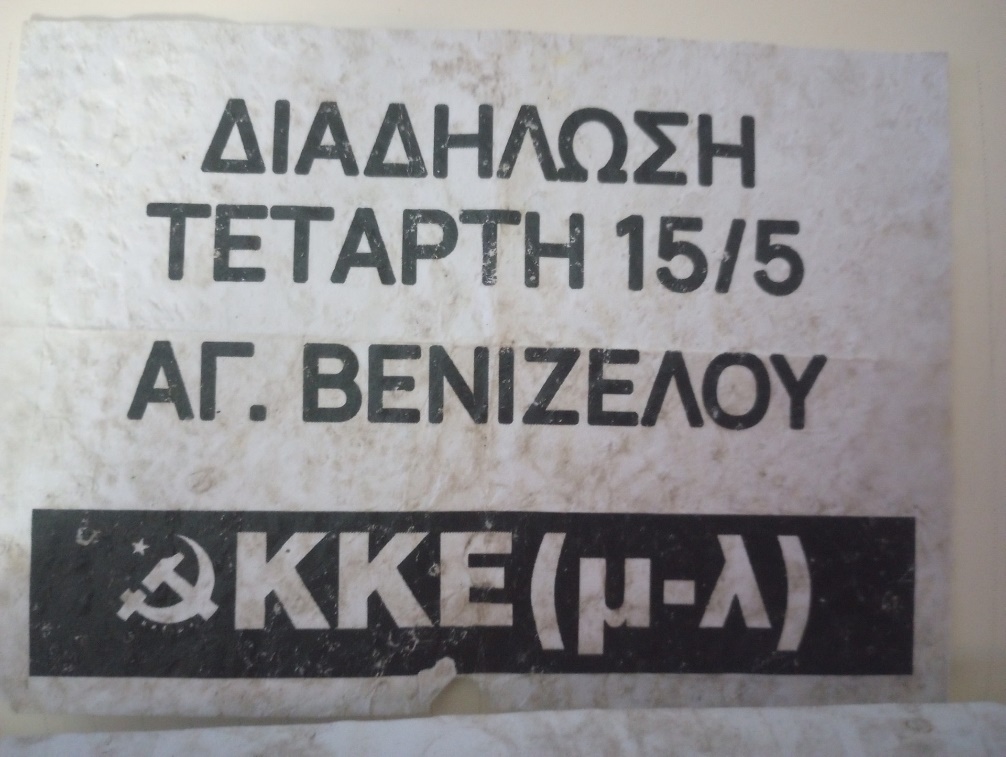

Groups on the political left understood the role that could be played by a more mobilized civil society translating assistance into political action. Tsakatika and Elftheriou (2013) reveal that the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) and the SYRIZA Party (Coalition of the Radical Left) tried to connect to trade unions and the new social movements, with the latter being more successful in such efforts.

Crises like the ones Greece suffered at the end of the 2000s involve having an informal civil society pick up the slack for the decline of formal organizations, until the latter can be put back together again, just as church soup kitchens played a bigger role during the American Great Depression, until the New Deal could commence. It was the same in Greece, at first. “The developments that have taken place in Greek civil society during the crisis are bound by existing socioeconomic conditions,” writes Simiti (2015). “Indeed, the organisational forms and repertoires of collective action that have prevailed in Greek civil society during the crisis correspond to ones that usually emerge in periods of severe economic crises. A shift from formal to informal associational repertoires in Greek civil society has been recorded, while the density of civil society has increased. “

But Simiti (2015) is concerned that something is different, a problem which could threaten the entire Greek political system. When more join a group, that does not mean group effectiveness. “However, these developments do not signal the growing strength of civil society. During the crisis, the reduced capacity of the state to provide the basic rights of citizens has led to a rapid deterioration in the quality of citizenship. In turn, social inequality and exclusion have undermined the strength of civil society. As the Greek case illustrates, increased associationism is a necessary precondition for a strong civil society, although during periods of severe economic and political crises it may not be sufficient (Simiti 2015).”

3.2: Ethnic and Religious Identities

There is a group that does not seem to be struggling so much in Greek society: the far-right. Such an ideology hypes nationalism with what they consider traditional Greek ethnicity and religion, using patriotic appeals to garner support. This was exacerbated not just during the economic crisis, but also with waves of immigration, used by the right to accuse the government of diluting a “pure” Greece with foreigners.

Many assumed that with the demise of the ultra-right “Golden Dawn” Party that those accused of being pro-Fascist would be in decline. Indeed, the organization is banned, and some of its members were jailed (Al-Jazeera 2023). Yet in the 2023 election, three far-right parties won seats, the only country in Europe where this happened, according to Al-Jazeera (2023). Perrier (2024) also reports that the right wing has gone “mainstream,” getting plenty of coverage by media sources with deep pockets. Perrier notes that there’s a strong anti-fascist element in cities like Athens, but Greeks may not realize how powerful those forces on the right really are.

3.3: Underrepresented Identities

Despite evidence of many emigrations to ancient Greece, the subject of those in Greece different from the dominant ethnic group is often an awkward one. This is partially from the debate over Greek origins, and also over the history of foreign occupation (Ottoman Empire) and clashes emanating from Greek neighbors in Balkan Wars (Turkey, Italy through Albania, Bulgaria, etc.).

“National and ethnic identities have for long been in the core of political tensions and even military conflicts within Greece and between Greece and its neighbours,” Myria Georgiou (2004) writes. “The concept of ethnic minority still remains a taboo and unacceptable concept for many policy makers, politicians and for the majority of the mainstream media; it is considered as a threatening political/propaganda concept that challenges, or even threatens the national interests and boundaries of Greece.” She notes that there are currently even using phrases like ethnic minorities is a touchy subjection “where the ideology of national homogeneity is still dominant.”

The Fulbright Foundation Greece (2024) reports “Foreigners are generally welcome, but the recent and sudden influx of immigrants has sometimes led to resentment. Due to the homogeneity of Greece, there are no big communities that represent diverse ethnic groups, except for immigrants and refugees. People from Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia are concentrated around Omonia and Patission, especially Plateia Victorias. There are numerous expatriate groups on Facebook and a growing Chinatown near Syntagma, as well as a Filipino community in Ambelokipi.”

This foundation also reports that in addition to ethnic and religious minorities, there is recognition of a growing LGBTQ+ population. “Greece is the birthplace of Eros and of the poet Sappho. Members of the Greek LGBT+ community frequently appear on mainstream television and several celebrities have self-identified as members. LGBT+ communities in the larger cities of Athens and Thessaloniki have become quite vocal and active (Fulbright Foundation Greece 2024).”

3.4: Political Polling

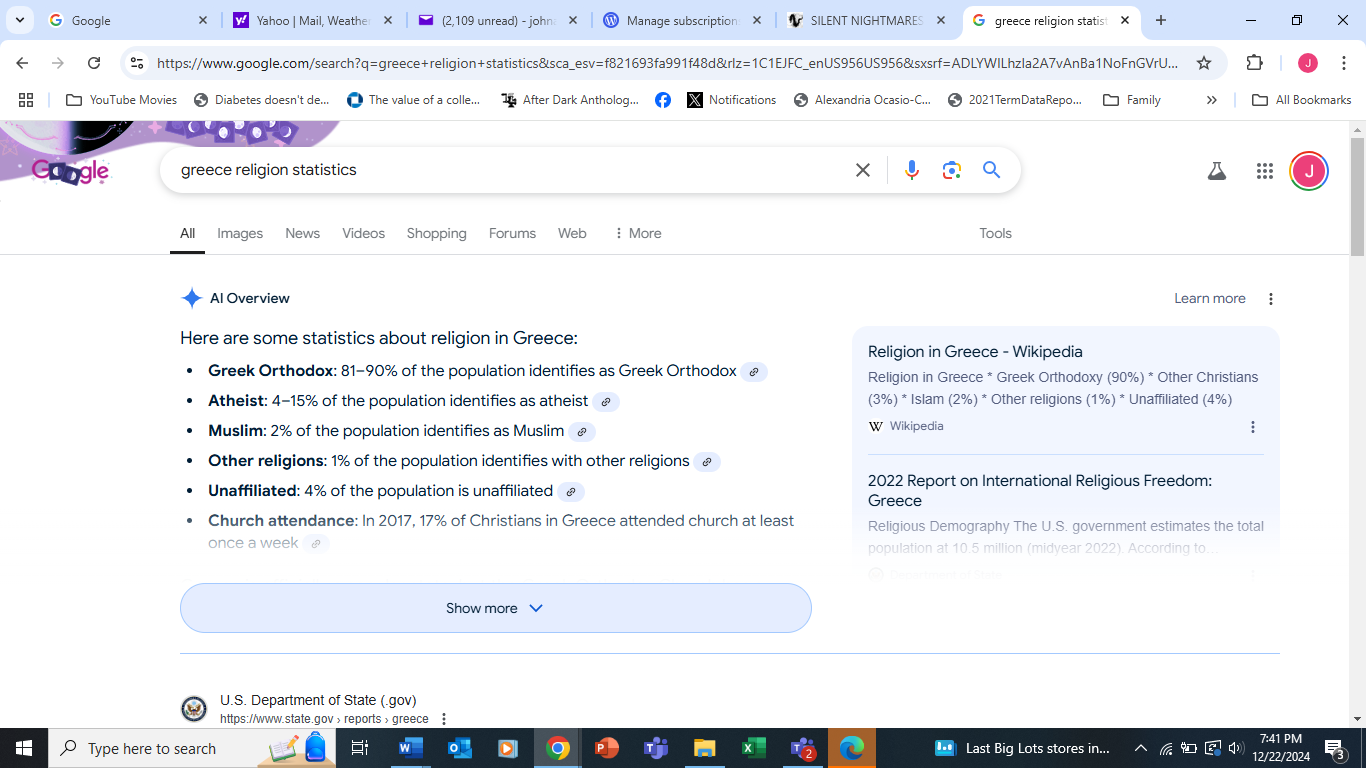

Like many European countries, Greece’s political system is extensively polled. The personal preferences of political parties are tracked over time, as Politico (2024) shows, in cases for more than 10 parties before and after the 2023 elections.

Greece also has the power of referendum, where the people can vote on some high-profile issues, like the 1974 decision of the Greeks to reject the monarchy in favor of a republic by a wide margin (Roberts, 1974) after the military regime fell. Traynor, Hooper and Smith (2015) report on the results of the 2015 referendum, and a big no vote on the country remaining in the Eurozone’s single currency, at the expense of tax increases and spending cuts.

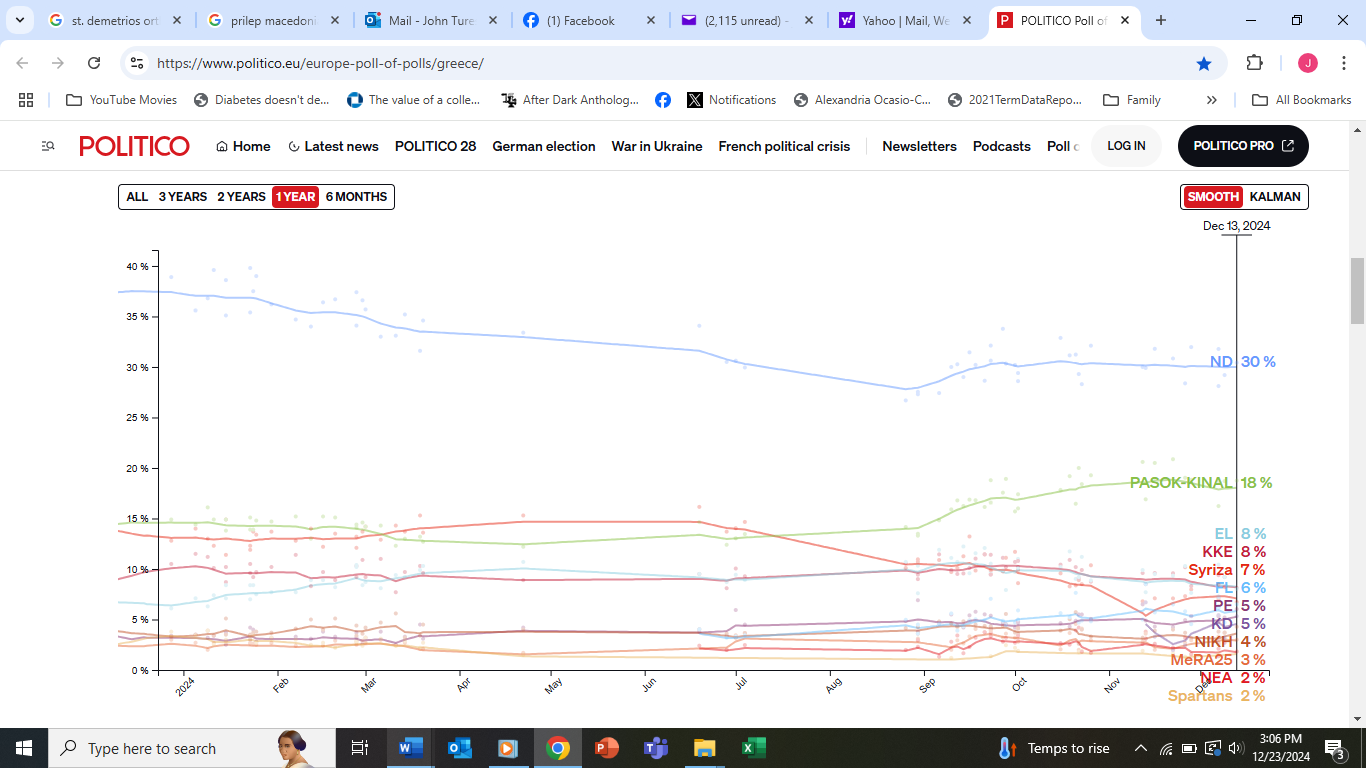

3.5: Governance

Freedom House’s (2024) report on Greece can be summarized by this quote. “Greece’s parliamentary democracy features vigorous competition between political parties, and civil liberties are largely upheld. Ongoing concerns include corruption, government surveillance, discrimination against immigrants and religious and ethnic minority groups, and poor conditions for irregular migrants and asylum seekers.” The country’s Freedom House score of 85/100 makes it a solid democracy, with positive scores for political rights, 35/40 (the ability to run for office, form political parties, etc.) and civil liberties (freedom of speech, the press, religion, etc.). Their score is a tiny decline from 88/100 in 2020, which is something to note.

Amnesty International (2024) documents the situation for Greek refugees, including the closure of migrant camps, and challenges to protests by Greek citizens. According to their report for 2024, “Reports of unlawful use of force in the policing of demonstrations persisted. Survivors of a shipwreck in which more than 600 people died blamed the Greek authorities for causing the incident. Human rights defenders continued to face criminalization for their work with refugees and migrants. An investigation by Greece’s data protection authority identified 88 individuals as targets of Predator spyware. Violations of the rights of conscientious objectors to military service persisted. Destructive wildfires resulted in the loss of lives and natural habitat amid concerns at the failure of the firefighting system.”

Section 4: Political Participation

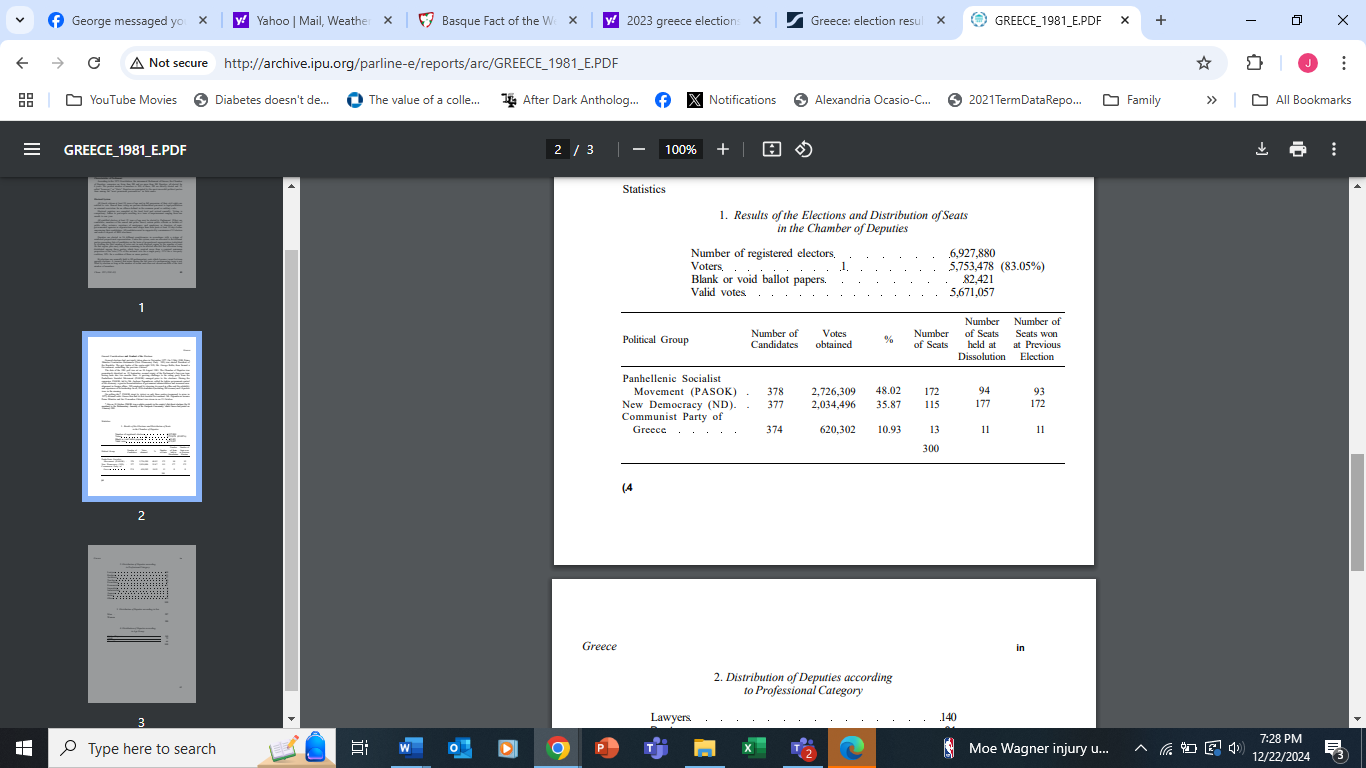

In 1981, the left-of-center PASOK (Panhellenic Socialist Movement) party won a landslide, one of the biggest elections since the end of the military dictatorship from 1967-1974 (Clogg 1982). The party boosted its fortunes by nearly doubling its prior election showing (from 25.34 percent to 48.0 percent) and boosting its share of parliament from just under 100 MPs to a strong majority of 172 (to the right-of-center New Democracy (ND) which fell 56 seats to 115 MPs). The Communist Party of Greece managed 10.94 percent, while no other party got more than two percent of the vote. PASOK succeeded by shedding its class-based rhetoric in favor of more moderate-sounding proposals (Clogg 1982).

This two-party system of the postwar dictatorship persisted for a number of subsequent elections until the Greek financial crisis during the Great Recession. Now new parties have emerged that threaten the two-party system of the 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s (Politico 2024).

The fortunes of parties are not the only change since the end of military rule. Women won the right to vote in 1952 (Efthyvoulou, Kammas, and Sarantides 2020). Papageorge-Limberes (1988) found that after the military dictatorship ended, more opportunities opened up for Greek women. Issues pushed for include civil marriage, an abolition of the dowry system, making divorce easier.

Women with more education adopted more modern approaches to politics, which include more political engagement, while women who are older or had more kids hew to a more traditional role for women, reminiscent of pre-democratic Greece (Papageorge-Limberes 1988). Efthyvoulou, Kammas, and Sarantides (2020) find that if there is a gender voting gap, it is only seen in Thessaloniki, and only related to whether women are in the labor force or not; those not working are more likely to vote conservative.

Sophocleous, Anastasiadou, Masouras, and Apostolopoulos (2023) claim that “poll results may tell us that the motives of the Greek voters are mainly result of their personal perceptions, rather than exogenous factors. In this respect, the political parties, could explode the particular fact, by giving emphasis to element such as the Integrity and the political background of their candidates, which appear to be more influential upon voters’ perceptions.”

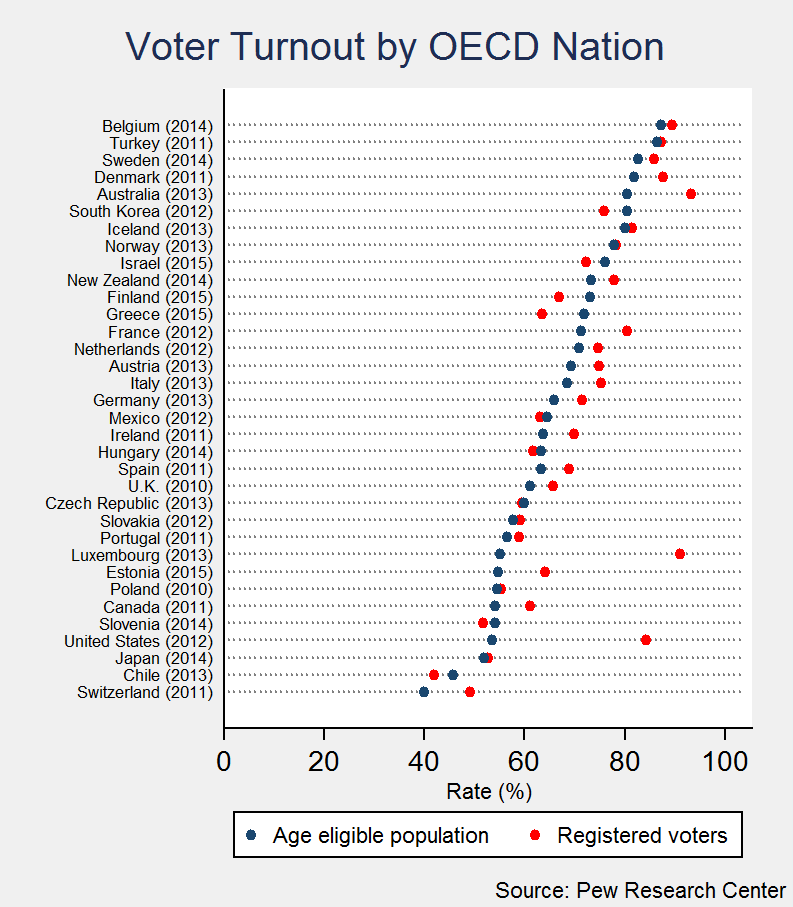

In fact, dismay with Greek politics has also taken its toll on voter turnout. From those heady days of 1981 with an electoral turnout of more than 80 percent declined to barely above 50 percent in 2024 for the European elections (Efstathiou 2024). Some blamed the heat wave of 2024, but others pointed to electoral fatigue and disaffection with existing political parties (Efstathiou 2024).

4.1: Political Parties

New Democracy on the right and PASOK on the left have been the two dominant parties since the mid-1970s when the Greek military exited power. The New Democracy Party is a Christian Democratic-style right-of-center party that supports more nationalism, a greater role for the church doctrine in politics, and a private sector with less interference from government regulations.

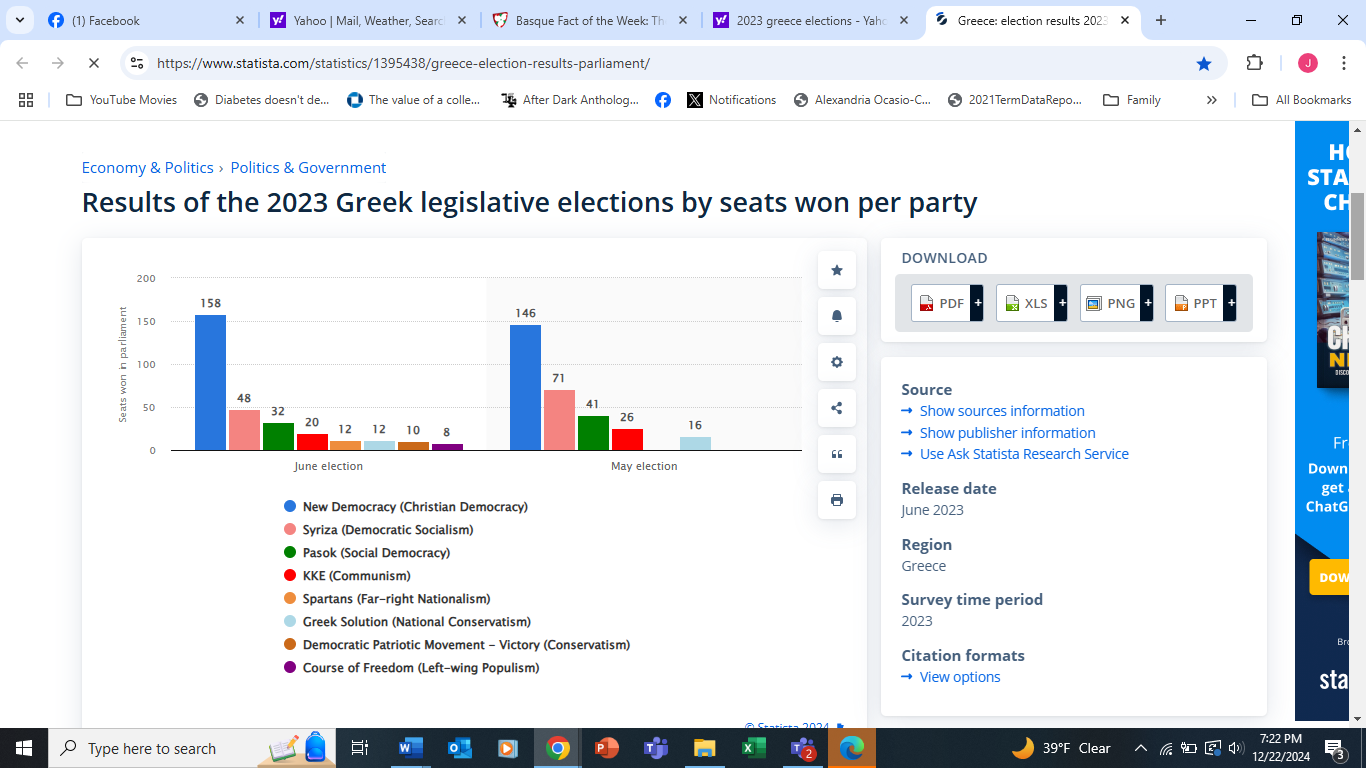

“In the parliamentary elections of 2023, the ruling New Democracy (ND) party of prime minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis was re-elected triumphantly,” Chryssogelos (2024) writes. “ND’s victory marks an unprecedented moment of centre-right dominance in Greece since 1974 and goes against the trend of the so-called ‘crisis of the centre-right’ elsewhere in Europe…. [The] ND’s strategy under Mitsotakis has been typical of the winning formula of other centre-right parties in Europe in previous decades. Yet, that this formula is now so successful in Greece owes much to the country’s post-crisis context, out of which the Mitsotakis leadership emerged.” The ND was also boosted by economic growth and effective management of the COVID-19 pandemic, while just as many being opposed by a left-wing fragmented among several parties. The party is now down to 30% support, a sizeable drop-off from their 2023 success.

PASOK or the Panhellenic Social Movement, is Greece’s center-left party, similar to the Social-Democratic Parties of Germany and Italy of the Socialist Party of France, or the Labour Party of Britain. Formed after the Greek military coup, the party, PASOK embraced a strong version of socialism which called for strong government regulations and a possible abandonment of Western military alliances like NATO (Britannica n.d.). But to win power as they did in the 1981 elections, and subsequent ballot contests, PASOK, like other European Socialist parties, had to moderate their views. PASOK won several elections until the Greek financial crisis, when they had to capitulate to European Union demands on the bailout package, agreeing to an economic austerity program that raised taxes and cut spending in 2010 (Britannica n.d.). PASOK now struggles to regain its former glory; it is now currently polling at 18% (Politico 2024) good enough for second place in Greece.

SYRIZA, originally wedged itself between PASOK on the Center-Left and the Communist Party of Greece on the extreme left-wing acting as though the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact never collapsed. A good analogy for this party is the American Progressive Party (Dimitrovski 2020), or France’s current Left parties, or the Party of Democratic Socialism in Germany. Emboldened by the drop in support for PASOK, SYRIZA prevailed in 2015, led by the bold Alexis Tsipras, who promised an end to austerity packages. Months later, Tsipras was forced to do an about-face, and accept another bailout package. The party was crushed in 2023 election, which led to Tsipras and in-fighting over the future direction of the party. Currently, the party has fallen into single digits for support (Politico 2024).

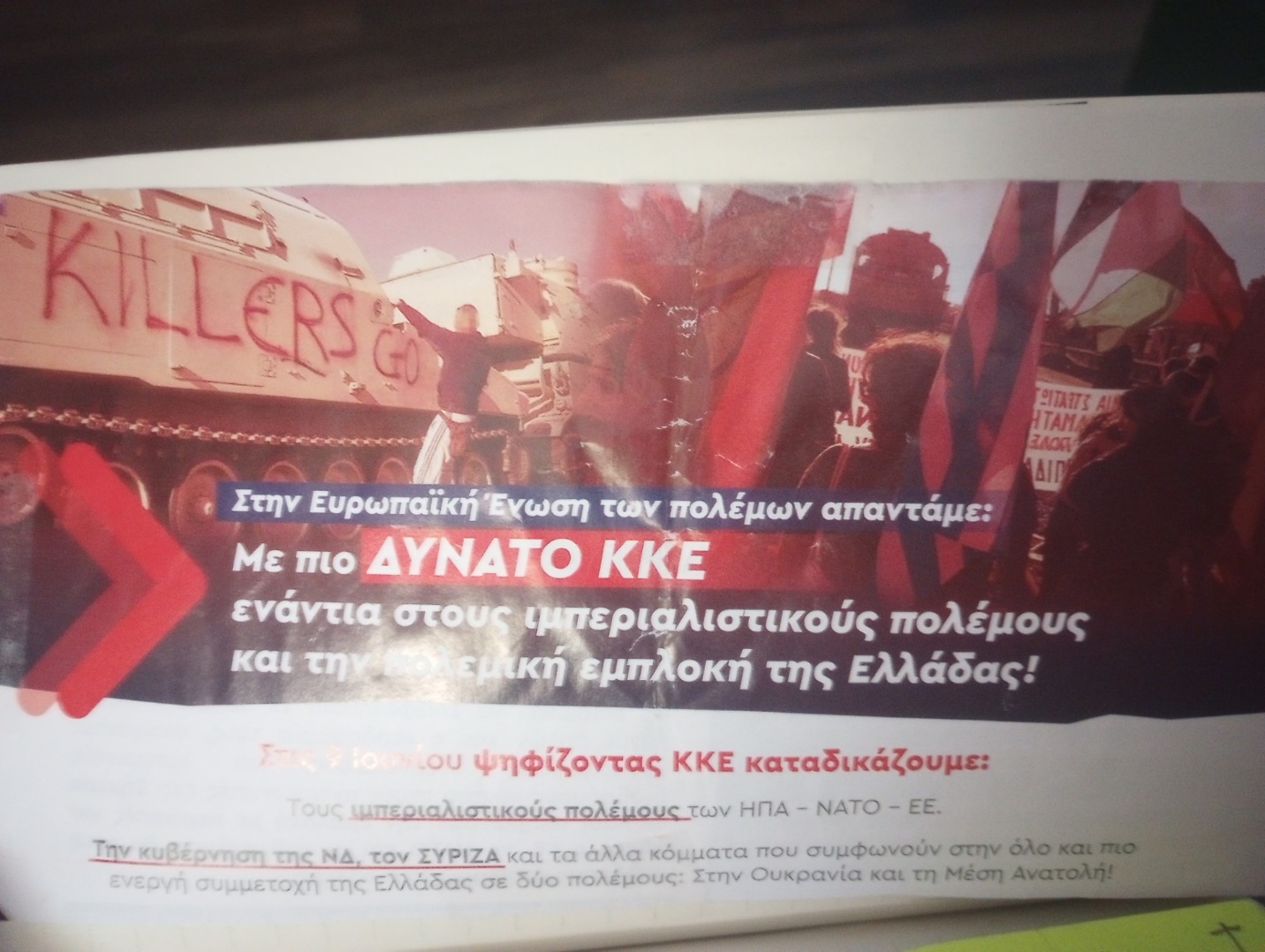

KKE is the Communist Party of Greece. The party’s legacy comes from its resistance to Nazi Germany, and its battles with the post-WWII regime supported by Britain and America. The party has hovered in support between 5% and 10%. When walking about Thessaloniki and Athens, it was the easiest to find their literature and stickers, calling for rallies. Currently the party support is at 8%, one percentage point better than SYRIZA.

A slew of right-wing parties have emerged in Greece, the result of economic and migration crises, emanating from the Middle East. Parties on the extreme right won 12 percent of the vote, with the newly formed nationalist group “The Spartans,” which garnered 12 seats (Smith ). They were supported by former members of Golden Dawn, the neo-Nazi organization now banned in Greece. We saw evidence of this group at the Ponthos Rally in Athens, seeking to whip up nativist support. This group resembles the hard right parties emerging across Europe in Scandinavia, Germany, France, and Spain (Smith 2023). Other parties of the far right, like Greek Solution and the Patriotic Movement, which earned between 3.5 percent and 4.5 percent of the vote (Smith 2023).

Other parties exist in Greece, now that the country has fragmented from a relatively stable post-1974 two-party system to a multiparty system. It remains to be seen whether such a system persists, or if these parties can form alliances and morph into stable coalitions.

4.2: Interest Groups

Interest groups, noted in the civil society section, are non-governmental groups that perform vital roles in the economic sector, but also lobby the political system on matters of policy. Of their function and importance, Rossetos Fakiolas (1987) writes “As in other Western European political systems, there are thousands of interest groups in Greece, performing different roles and having varying relationships with the institutional structures of the State. The groups inevitably cover a wide range of the interests, from strictly economic to cultural, educational, ethnic, religious, and conservationist. The negative effects of interest groups in creating rigidities in the economic and social system have been more than offset by their stabilising influence in a society characterised by a succession of the abnormal political, economic and social developments in the last 50 years.”

Greek interest groups, like the political parties, were once more centralized, but are becoming more spread across multiple groups. For the business sector, there is the SEV, or Hellenic Federation of Enterprises. SEV (n.d.) lists almost 50 different business associations under their umbrella organization. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the Hellenic Republic (2022) lists even more groups. The function of these groups is to advance their businesses, influence government to deregulate their industries, open foreign markets to their products, and provide economic advice to government.” The historic role of the SEV is not without controversy. While under the Greek military junta, the business groups did support liberalization, but it was more about repairing ties with the European Economic Community (EEC) and supporting an authoritarian transition to electoral politics, rather than a push for a strong democracy, according to Tsakas (2018).

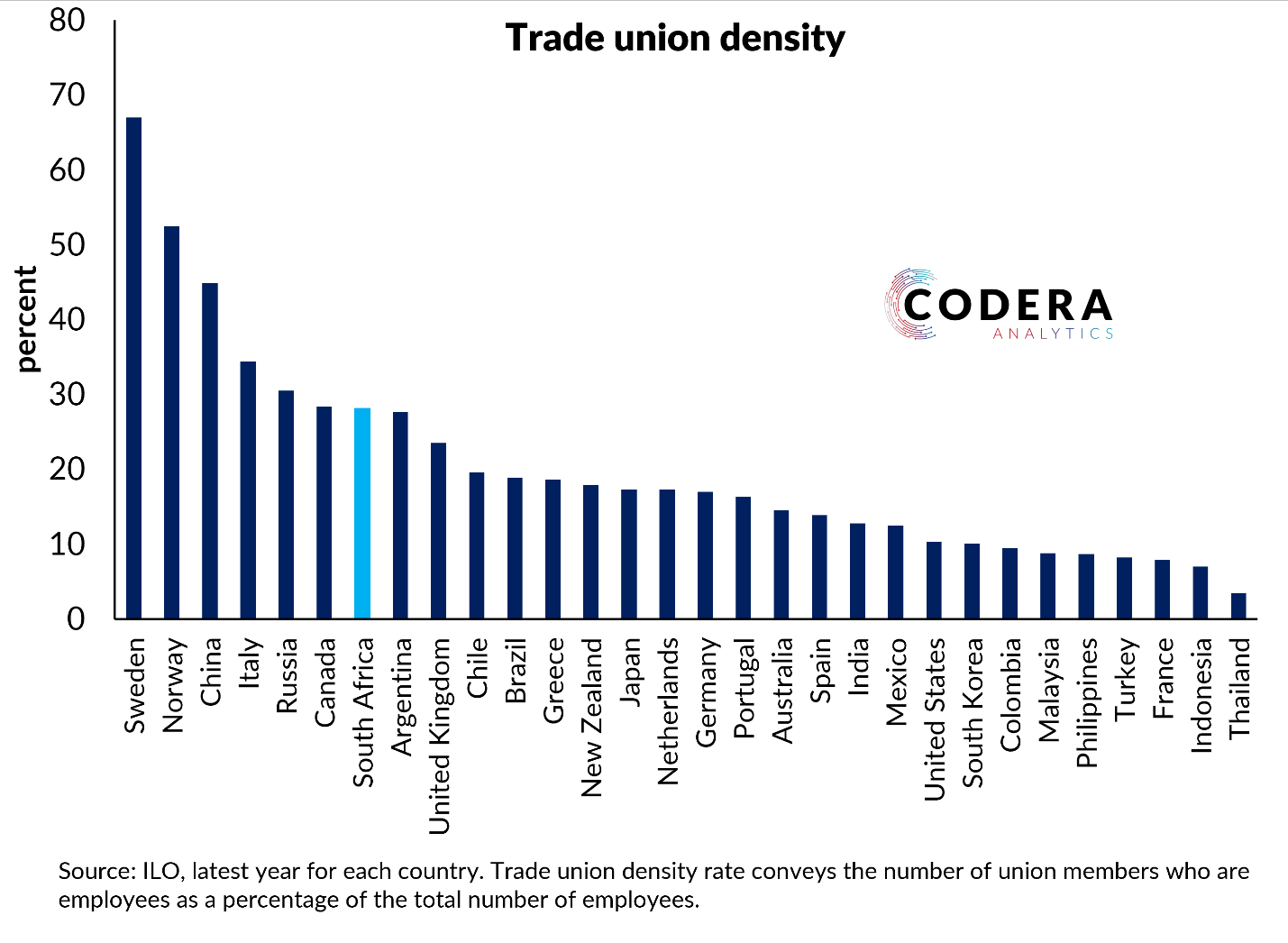

As for workers’ organizations “Trade unions were officially inactive during the military dictatorship (1967–1974), although many unionists participated actively in the struggles for the restoration of democracy,” writes Giorgos Bythimitris (2021). He adds that power to unions did not return until the election of PASOK’s Andres Papandreou in 1981, a move that paid dividends for the unions when the Socialists prevailed. “The law on trade unions updated in 1982, which laid the groundwork for proportional representation, marked the beginning of a very active period – by Greek standards – for trade unions, who were involved in policy-making and social dialogue. However, close links between the (governing) parties and trade unions was already evident at that time, subsequently resulting in a system of ‘give and take’” Additionally “the enlargement of the Greek public sector was also an outcome of the new roles and responsibilities that the Greek state assumed within a more complex and interconnected international environment in the last quarter of the twentieth century. Suffice to say that, even at its peak, average employment in the Greek public sector was close to the EU15 average (Bythimitris 2021).”

The unions in Greece organized into a hierarchical structure. “In terms of trade union structure, Greek law makes provision for three different levels: a) First-level trade unions: these unions are legally autonomous and their activities are generally limited to a particular region or business. They may be part of a national sectoral trade union or regional trade union confederation (second-level). b) Second-level trade unions: these are either national industrial or occupational confederations (sectoral trade unions such as GENOP-DEI) or regional organisations, such as the Centre of Athens Labour Unions (EKA). c) Third-level trade unions: national trade union confederations, such as GSEE and ADEDY, made up of second-level trade unions (Bythimitris 2021).”

Further advances were made in collective bargaining and flexible employment contracts. But the power of the unions was buffeted by the Great Recession economic crisis, with a downturn that hurt workers, as well as budget cuts that affected public sector employment. Greek unemployment hovers around 15.6 percent, with women facing more problems (19 percent jobless) than even men in Greece (12 percent unemployment), according to Bythimitris (2021). This decline of the unions seems to go hand-in-hand with the troubles facing the parties of the Left.

Many farmers in Greek agriculture have joined Agricultural cooperatives (AC), created to offset some of the challenges from economic (large farm and agribusiness competition, reduced access to credit, downturns that dry up demand) and environmental problems (climate changes and disaster), covering business functions ranging from distribution, processing, and marketing, as well as manufacturing (Kalogiannidis, Karafolas, and Chatzitheodoridis 2024).

As Patronis and Mavreas (2004) report, the agricultural sector has been the beneficiary of “the large extension of agricultural credit, as well as the constantly increasing involvement of the government and banks in their internal affairs.” Like other farmers, there is a desire for protection from international competition; there are also concerns over being co-opted by political parties.

Currently, the country’s agricultural interest group system of cooperatives is struggling. “According to the latest update of the National Register of Agricultural Cooperatives in 2023, there are 1,056 collective entities listed – perhaps more than any other European Union member-state – but they are estimated to produce the lowest value per cooperative,” writes Dimitra Manifava (2024). “Not to mention their outstanding debts, which amounted to around 2.5 billion euros a few years ago. For example, according to the latest data available from Eurostat (referring to the year 2020), only 0.7% of farm owners in Greece had a full agricultural education – in the sense that after compulsory schooling they attended a training program of at least two years and studied a subject related to the primary sector at a higher level. This is the lowest percentage in the EU, with Greece coming at a par with Romania.”

Comparative politics professors identified “new social movements” to describe the era beyond World War II, for what they call modernism, based upon traditional economics and “kitchen table issues,” due to voter concerns of the time frame after The Great Depression and World War II, where shortages were of paramount concern. Such motiving issues persisted throughout the 1950s and into the early 1960s. But a new generation of voters born after the 1930s and 1940s, did not know such trying economic times. Raised in the era of post-WWII prosperity, such voters became more obsessed with non-economic issues, like environmentalism, feminism, religious concerns, etc. Most scholars identify this era of “post-modern” to emerge in the late 1960s, 1970s and beyond, the very time frame where the military regime was forced from power.

In writing about the new social movements of the post-modern era, Marilena Simitis (2002) contends “[T]he Greek case studies represent significant variations in regard to the ‘ideal type’ of new social movements as depicted in the literature. These differences originate to a certain degree from Greek new social movements’ different cultural and political environment. The Greek social movements had to face a strong statocratic and partocratic society, where there was lack of an autonomous social movement sector. This led to the formation of semi-autonomous, party-affiliated social movement organisations. Moreover, the Greek political culture has been rooted on two different geopolitical visions. The one has pointed to a more traditionally oriented, inward looking political orientation hostile to Western values and the institutional arrangements of modernity. The other has been a modernising, outward looking orientation, adopting Western institutions and values.”

Indeed, with the economic collapse of the late 2000s, along with the bailout battles, it seems that modernism of old has returned to Greek politics. Of Greece and new social movements, Themelis (2015) penned this: “In any case, disappointment with politics, brutal austerity and a dysfunctional democracy do not mean lack of hope. By contrast the social movements that have been emerging and solidifying across Greece, the experimentation with new and old forms of politics, such as the squares movement and the rise of Syriza in national and international prominence, these are serious reasons to be optimistic.”

Battles over economics were now given an international dimension, as Greeks disagreed over whether to accept international bailouts. The spread of immigrants to the shores of Greece and its islands created a new social movement that added a new front: support of helping these refugees or oppose their entrance on nationalist grounds.

Themelis (2015) adds “The characteristics of the class struggle will be more accentuated the longer the crisis endures and the further it deepens. There are strong class forces that will eventually seek to reconcile the material with the symbolic fields….The plethora of social movements in this small part of Europe are signalling that, at least for now, a new form of politics, which is more imaginative, daring and democratic, is being created. If this politics is to lead to much-needed victories in the material and the symbolic fields, it will have to fight on the terrain of class struggle. This is where hope is to be found. But this kind of hope is part of the long process of liberation from an exploitative system that urgently needs replacing and not merely re-decorating.”

4.3: Electoral Systems

Who gets to vote? According to the Hellenic Parliament (n.d.), the rules show “The electorate consists of all Greek citizens who have the right to vote. This right is granted to individuals who are at least 18 years of age, or shall turn 18 on the year of the election, have the capacity for legal act and are not the subject of an irrevocable criminal conviction for felonies listed under article 51 par. 3 of the Constitution. Eligible electors must be registered in the electoral roll to exercise their voting right.” The rules also state that immigrants legally residing in Greece may vote in European Parliament elections (if a member of another EU state) and municipal elections, under certain circumstances.

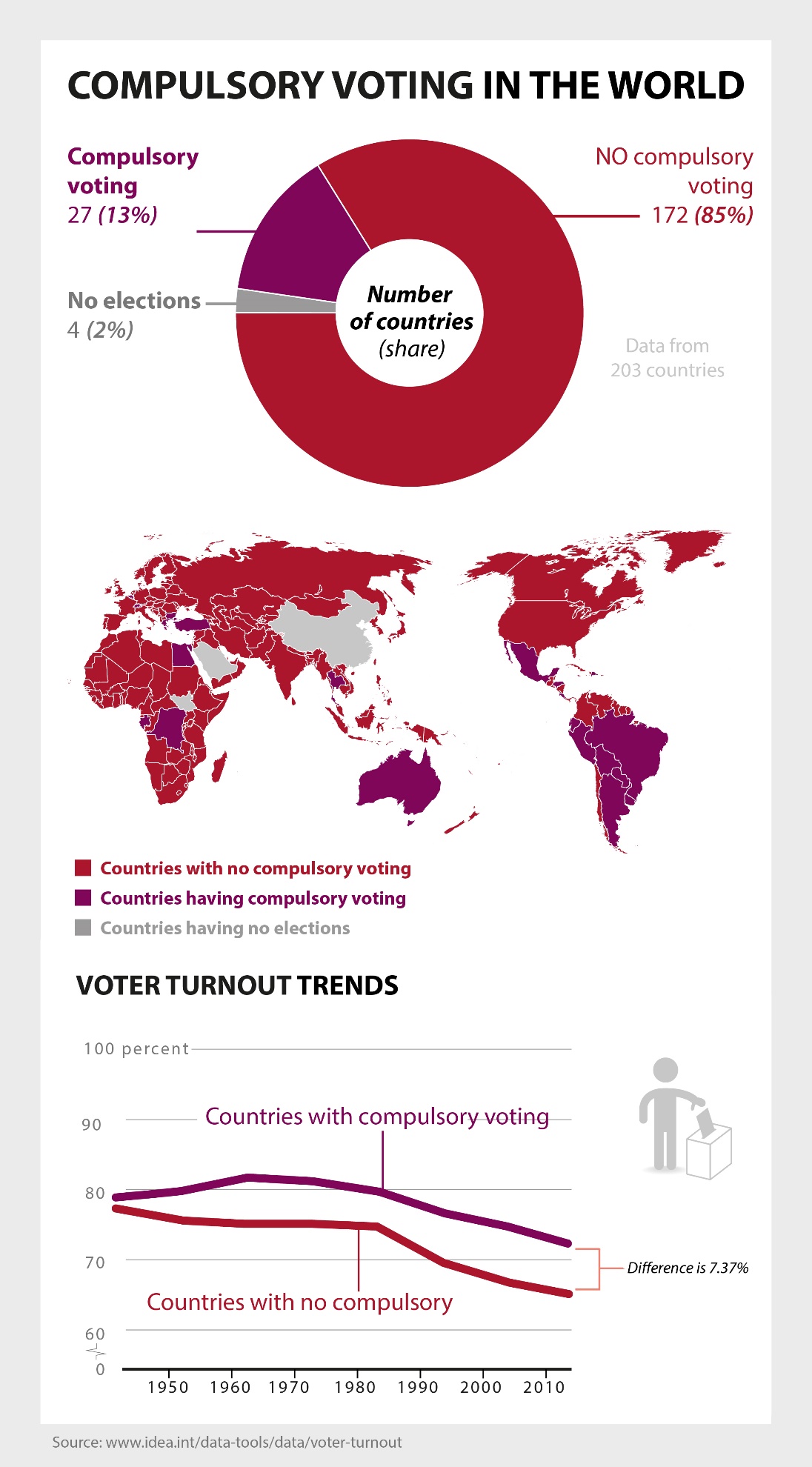

The Greek Constitution also provides several measures to ensure a more direct form of democracy, according to the Hellenic Parliament (n.d.). This varies from the principle that protects voters from indiscriminate exclusion, a 1 citizen 1 vote principle, secrecy, and compulsory participation. At one point, there were sanctions for not voting, though many of these more severe punishments have been removed in the last two decades. Moreover, the rules for absentee ballots have also changed, allowing more flexibility. The Greek Constitution also rejects the principle of indirect voting, whereby some unelected “electors” cast the real ballot, or legislators at the local level picking the upper chamber of the national legislature, as you see in other countries.

On the website for the Hellenic Parliament (n.d.), it outlines the power of political rights in Greece.

“Α) Universal ballot- according to this principle, only citizens that do not fulfill the minimum requirements provided by the Constitution may be excluded from the electorate. The ordinary lawmaker may not provide additional reasons to deprive an individual of the right to vote;

Β) Equal ballot- a principle of dual significance, i.e. i) one citizen -one vote and ii) all votes are legally equal;

C) Direct ballot- according to this principle, there should be nothing standing between the voter and the outcome of the electoral process. In other words, it is not possible for voters to choose electors to elect MPs;

D) Secret ballot- a principle to ensure that the intent of the voter shall not be made known to others;

Ε) Compulsory ballot- according to this principle the exercise of the voting right is compulsory. Let it be noted nonetheless that the Constitutional revision of 2001 removed a clause by virtue of which penal sanctions could possibly have been imposed by law on constituents who failed to take part in the electoral process;

F) Simultaneous conduct of elections throughout Greece- Revised article 51 par. 4 of the Constitution refers to possible exceptions to this rule in case constituents (voters) are abroad, as long as all votes are counted simultaneously and the outcome of the electoral process is publicized at the same time everywhere;

G) The principle of exercising one’s voting right in person, making the physical presence of a voter imperative, currently applies to voters who are on Greek territory. Revised article 51 par. 4 of the Constitution offers Greek voters abroad an option to exercise their right to vote in absentia ‘through postal and/or other appropriate means’.”

The Hellenic Parliament (n.d.) also documents the fascinating evolution of elections in Greece since the country’s independence from the Ottoman Empire in the 1830s. Over time, the country has adopted some of the classic electoral systems from comparative politics: the majoritarian system as well as the proportional representation system.

[T]here are basically two electoral systems: the majoritarian system (which designates the candidate or political group (i.e. the party) who got the majority of the votes cast in one constituency) and the proportional representation system (which allocates seats per constituency proportionally to the votes each candidate or party received),” the Hellenic Parliament (n.d.) illustrates. “Both electoral systems have actually been used in Greece. In the period between 1844 and 1923 general elections were held on a majority election system (there were actually no ballot papers or lists but rather ballot boxes divided in two sections, one black for ‘nays’ and one white for ‘yeahs’, and voters cast little marbles made of iron on either side.) Both systems were also used in rotation from 1926 through 1956 when the proportional representation system was opted for, in its various forms.”

500 BC – Pebble Voting

https://dataphys.org/list/visualizing-opinions-with-pebbles/

Sometimes, the system can seem a little complicated, not unlike some of the humorous complex electoral systems spoofed by characters in films from the comedic British group Monty Python. As the Hellenic Parliament (n.d.) posts on its site “Let it be noted that by virtue of art. 54 par. 1 of the revised Constitution, the electoral system is determined by law, i.e. a statute which applies only once the next elections have been held, unless provision is made for an immediate enforcement of the electoral law just as long as a 2/3 parliament majority adopts it.” But what it means is that it takes a supermajority of parliament to agree to a significant change in how elections are conducted in Greece. Recently, this came into being as Syriza sought to institute a more proportional representation change that they hoped would augment their numbers.

For the most recent elections in 2023, Reuters documents how the election system works. “The repeat election will be held under a semi-proportional representation, or reinforced proportionality, with a sliding scale seat bonus.” Reuters (2023) explains. “Parties need to secure at least 3% of the vote to enter parliament for a four-year term. Under the new system, the winning party is awarded a bonus of 20 to 50 seats. It receives 20 seats outright if it gets at least 25% of the vote, and can get up to 50 seats if it gets about 40% of the vote.”

Like many European countries, Greece has a minimum threshold for parties to acquire office, to weed out more extreme parties more intent on overthrowing the system. Without such a minimum, the once-small Nazi Party could cause havoc in Germany in its early stages. Also, like many EU countries, Greece also has a built-in system to reward winning parties, bonuses that make it easier to reach the threshold for a party to actually govern. When no majority is reached, coalitions must be formed, with the party receiving the largest plurality or share of the vote, getting the first opportunity to build such a coalition. If the 50%+1 threshold is not reached, a minority government typically made of the largest vote-getter runs a caretaker system until new elections can be called.

In conclusion, by studying both the history as well as the modern forms of Greek government, one can see that the country has adopted examples of authoritarianism as well as democracy, in addition to a myriad of forms of democracy. Despite declines in voting participation, the broad range of societal groups and parties reflects a dynamism that shows perhaps the only constancy in Greek politics is change.

Section 5: Greek Formal Political Institutions

For a country credited with inventing the term, and the practice, of democracy, Greece has a lot to celebrate. Emerging from the struggles of the economic collapse, Greece was ranked one of the most democratic countries in the world, earning the rare distinction of a “full democracy” by The Economist. But despite the strong ranking, the measure of “functioning of government” has the country ranked behind many full democracies from Western Europe. In this chapter, we’ll examine fully the country’s institutions, what works, and what could work better.

5.1 Democracy

In The Greek City Times, Bill Kouras (2024) writes In the category of ‘full democracy,’ Greece has been upgraded by the ‘Economist’ magazine in its annual report, ‘Democracy Index,’ for 2023. This marks the first time since 2008 that Greece has achieved this ranking, placing the country one category above the United States and member states of the European Union, such as Italy, Belgium, and Portugal, which are considered ‘flawed democracies.’”

That is quite an accomplishment for Greece, one of 167 countries examined, one of the eight percent considered a “full democracy.” Additionally, nearly every continent experienced cases of setbacks when it came to institutions enabling people to rule. But The Economist lauded Greece making “postal voting” possible (Kouras 2024). This backs up what The Freedom House reports.

A closer look at that Economist ranking shows that Greece scored well on “electoral process and pluralism” as well as political culture and civil liberties. But when it came to “functioning of government,’’ Greece’s score left room for improvement, as the country ranked at or behind other European countries considered “flawed democracy” such as Belgium, Malta, Italy, and Portugal (Kouras 2024).

There’s a battle among scholars of Ancient Greece about democracy, not about the meaning of the word, but whether it was a positive force or a pejorative term to mean “mob rule,” by elites stung by being outvoted or having to deal with unruly subjects. Long before Aristotle wrote, there were already plenty of polities from Southern Europe to the modern Middle East, some with a form of democracy, and others of a more authoritarian character, not unlike the Greek military rule of the 1960s and 1970s.

According to the BBC “The origin of the Athenian democracy of the fifth and fourth centuries can be traced back to Solon, who flourished in the years around 600 BC. Solon was a poet and a wise statesman but not – contrary to later myth – a democrat. He did not believe in people-power as such. But it was Solon’s constitutional reform package that laid the basis on which democracy could be pioneered almost 100 years later by a progressive aristocrat called Cleisthenes (Cartledge 2011).”

Professor Paul Cartledge (2011) adds “Cleisthenes was the son of an Athenian, but the grandson and namesake of a foreign Greek tyrant, the ruler of Sicyon in the Peloponnese. For a time he was also the brother-in-law of the Athenian tyrant, Peisistratus, who seized power three times before finally establishing a stable and apparently benevolent dictatorship. It was against the increasingly harsh rule of Peisistratus’s eldest son that Cleisthenes championed a radical political reform movement which in 508/7 ushered in the Athenian democratic constitution.”

“This demokratia, as it became known, was a direct democracy that gave political power to free male Athenian citizens rather than a ruling aristocratic class or dictator, which had largely been the norm in Athens for several hundred years before,” Becky Little (2024) with the History Channel posts. “Athens’ demokratia….lasted until 322 B.C.” She also notes some of the scholarly debate about whether it was the first of its kind.

As the BBC reports “Finally, in 322, the kingdom of Macedon which had risen under Philip and his son Alexander the Great to become the suzerain of all Aegean Greece terminated one of the most successful experiments ever in citizen self-government. Democracy continued elsewhere in the Greek world to a limited extent – until the Romans extinguished it for good (Cartledge 2011).”

The question is whether modern Greek democracy can survive. The Economist gives the current system high marks, but economic, immigration, and environmental challenges threaten the regime. Parties on the far left and hard right want to take the country in a different direction. Cynicism seems to be seeping in, given the lower political participation in recent years (a decline of at least ten percentage points (IFES 2024). Greece also had several cases where a dictatorship and a military takeover overthrew the cradle of democracy. The answer to the country’s survival comes from the institutional capacity of the Greek political system.

5.2 Legislative System

According to The Hellenic Parliament (2019), “The Parliament is the supreme democratic institution that represents the citizens through an elected body of Members of Parliament (MPs). In the current composition the Parliament consists of 300 MPs.”

IFES (2024) provides the results of the 2023 election. Currently, the right-of-center party New Democracy has 146 seats or 40.79% of the vote, while the leftist party Syriza has 20.07% of the vote, and 71 seats. PASOK (Movement for Change), the left-of-center party has 41 seats, because the party received 11.46% of the vote. The Communist Party of Greece (KKE) netted 26 seats by virtue of getting 7.23% of the vote. Finally, there’s the Greek Solution (LE) which has 16 seats, and a vote share of 4.45%. New Democracy expanded their lead into the second round, with enough for a majority in parliament.

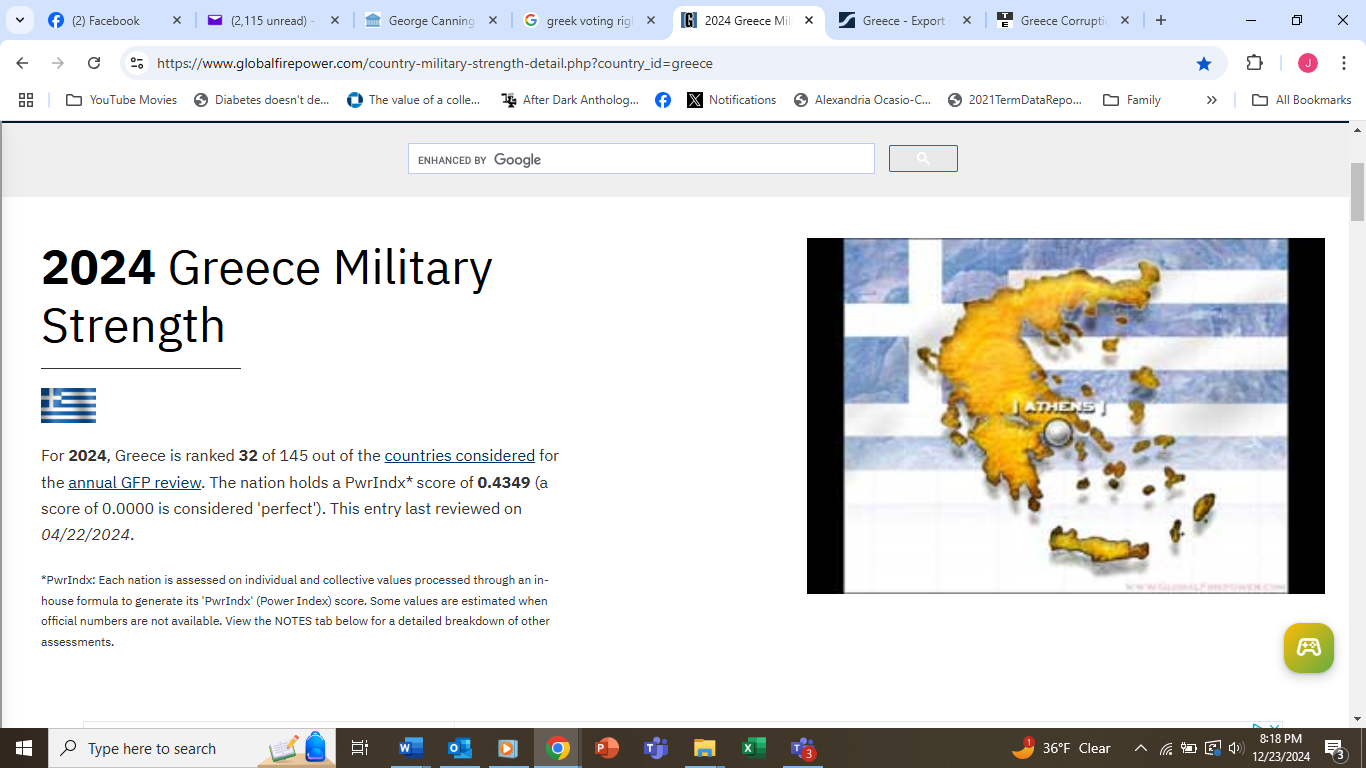

Sometimes, a measure with widespread popular vote is like to pass with very little opposition. For example, the Hellenic Parliament passed a budget that increased defense spending. This is not a surprise for the conservative New Democracy party, but for the parties of the left, it is a surprise. Yet surveys showed Greeks concerned about their security situation, especially in the Aegean Sea, perceiving a threat from a more bellicose Turkey (Michalopoulos 2024).

In other cases, parliaments face a contentious vote, requiring every vote just to pass. In March of 2024, the New Democracy party introduced a bill that would expand access by foreign private universities to enter the Greek education market, claiming that many Greek students leave the country to study abroad (Reuters 2024). Parties of the left strongly opposed the measure, claiming that such universities would drain the public colleges of students and revenue. But despite student protests, the measure passed on a vote along party lines, 159-141 (Reuters 2024).

5.3 Executive System

When determining who is in charge of the executive branch, it is important to note that there are two offices. One is the President of Greece, currently Ekaterini Sakellaropoulou. She’s the Chief of State, indirectly voted upon by the Hellenic Parliament. Greek Presidents can serve two five-year terms, and Sakellaropoulou has held office since 2020. A chief of state represents the country on the international stage, and officially confers the head of government position, or prime minister. Having a relatively non-partisan person in this position keeps the job from conferring too many benefits on a single party figure, an advantage that American and French Presidents get, as well as Turkey’s new presidential system.

The Greek Prime Minister, the head of government, leads parliament on getting legislation passed. He or she is voted on by a majority of parliament. Currently, the Greek Prime Minister is Kyriakos Mitsotakis of the New Democracy party. Though the Greek President officially declares who the P.M. will be, that office is chosen by a majority of the Hellenic Parliament. If no party has a majority, a caretaker government is appointed until new elections can be called to see if the voters are ready to pick a new majority. As with other parliamentary systems, parties can also form coalitions to provide that majority. It usually involves a distribution of cabinet offices, the ones that run the agencies in the executive branch.

After the initial May 2023 election, no party received a majority (Liakos 2023). The three parties with the most votes (New Democracy, Syriza and PASOK) could not agree upon a coalition, so President Katerina Sakellaropoulou appointed a caretaker government to be led by Judge Ionnis Sarmas, which would last until new elections could be held to see if the voters would pick a party with a majority. Those elections were held in late June (Liakos 2023).

In Greece, like other parliamentary systems, the legislature can remove the prime minister with a vote of no confidence, if economic times are hard, or if a scandal emerges that would discredit the government. Certainly, the opposition has every incentive to see the government fall. Members of parliament who are part of the majority, or the majority party, have a tough decision to make: should they get rid of the prime minister and the cabinet members, knowing that they or their party could lose their majority, or their jobs, if they are in the ministry? On the other hand, without a change, the whole party could go down the drain in the next election, so some political calculations need to be made.

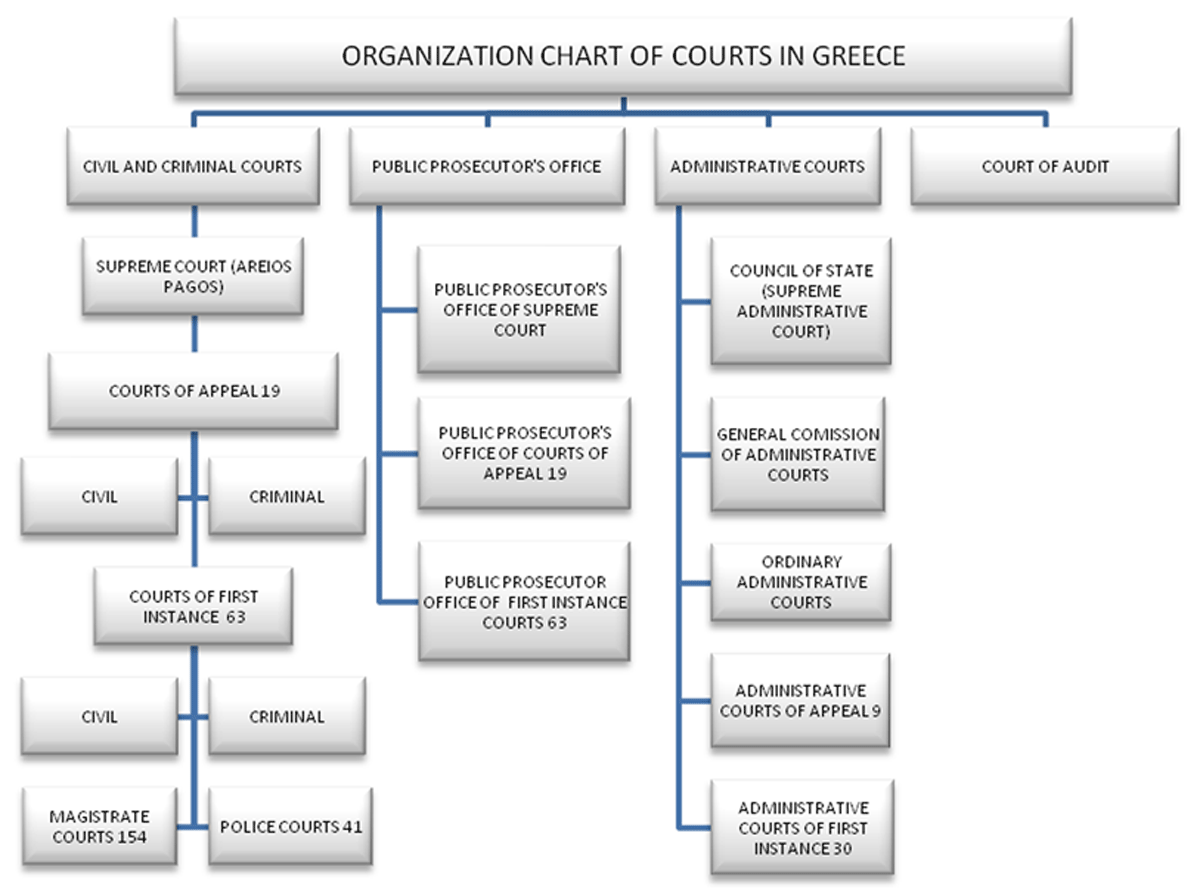

In March of 2024, a rare no-confidence vote was called for Prime Minister Mitsotakis regime, after a deadly February 2023 crash that killed nearly 60 Greeks, many of whom were students on Spring Break (Associated Press 2024). Their passenger train was accidentally put on the same track as a freight train, which caused the collision. Normally, a train crash wouldn’t be enough to topple a government, but there were rumors of a government coverup into the train investigation, one that a number of Greeks believe happened, and several parties of the left called for the motion (Associated Press 2024). However, the Hellenic Parliament voted 159-141 against removing the Prime Minister from the New Democracy party (Associated Press 2024).