2 France

Helen Chang

Helen Chang is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Eugenio María de Hostos Community College of The City University of New York (CUNY) in the Bronx, New York. She holds a B.A. in International Relations and French and an M.A in Sociology from Stanford University and a Ph.D. in Political Science from the CUNY Graduate Center. Her research interests include municipal election reforms, the structure of local electoral management bodies, and teaching and learning in political science. Helen has contributed a Community Mapping assignment and Design Your Own Comparison Indicator assignment to APSA Educate, APSA’s open education resource portal. She also served as a member of the 2024 TLC at APSA Program Committee and as the co-chair of APSA Committee on the Status of Community Colleges in the Profession from 2023-2025.

Chapter Outline

Section 2: Ethnic, Religious, and Cultural Identity

Section 3: Political Culture and Civil Society

Section 4: Political Participation

Why Study this Case?

Starting with the ancien régime, which can be characterized as an absolute monarchy, the French political order has also included empires, a revolutionary dictatorship, a fascist regime, provisional governments, and parliamentary and semi-presidential democracy. The French case illustrates wide ranging forms of political life from authoritarianism to democracy, along with 15 different constitutions in over 200 years of its post-French Revolution history. The French Revolution (1789-99) laid the foundations for modern democracy in Europe and a political culture that emphasizes French citizenship and equality. In addition, the post-World War II Fifth Republic (1958-present) broke the tumultuous cycle of revolutions, authoritarianism, and unstable democracy, as well as established a statist political economic approach, which still provides benefits and worker protections that are no longer commonplace in developed democracies. Finally, France has been a core partner in the creation and enlargement of the European Union (EU). While France has committed to economically and politically unified Europe, the French economy has slowed, and both France and the EU have begun to question France’s leadership role within the EU.

Section 1: A Brief History

Modern day France is made up primarily of the lands that the Romans called Gaul, which also included what is now Belgium and Luxembourg, as well as parts of Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany, and Northern Italy. Roman control of Gaul was established in the Gallic Wars (58-50 BCE) through the conquests of Julius Caesar. With the end of Roman Gaul in the 5th century, the Germanic Franks under Clovis I, the founder of the Merovingian dynasty, unified much of Roman Gaul under a new name, Francia for Frankish lands. Frankish rule continued with the Carolingian dynasty in the mid-8th century, and through Charlemagne’s expansion into old Roman lands, Francia became part of the Holy Roman Empire. During the Middle Ages, the Kingdom of France emerged from western Francia in the late 10th century with the founding of the Capetian dynasty, and in the late 12th century, Philip II was the first to call himself the King of France. A succession dispute between England and France sparked the Hundred Years’ War in 1337, which was fought primarily between House of Plantagenet, who ruled England, and the House of Valois, who ruled France. The war ended in 1453 with a French victory that drove the future development of French nationalism and monarchic power. Over the next 300 years in what is called Early Modern France, a centralized absolute monarchy emerged, with the development of military and financial organization and a professional bureaucracy. This brief history will illustrate the rise of the modern nation-state from Early Modern France, the French Revolution, and the Napoleonic period, democratization under the Third and Fourth Republic (1870-1940 and 1946-1958), to the stable democratic state under the Fifth Republic (1958-present).

1.1: Early Modern France (1453-1789)

The ancien régime, which describes the Kingdom of France before its toppling during the French Revolution, includes France in the Middle Ages and Early Modern France. Initially in medieval France, military and political power was largely decentralized. The royal bureaucracy and court was small with a limited reach. Nobles were not unified as a class, rather they had local bases of power, through their own lands and military organizations and their roles in the influential parlements, or regional judicial appeals courts. The three-estate system was also established during this time with the First Estate, which was comprised of Catholic clergy. The Second Estate included landed and titled nobility, and the Third Estate held the remaining population of commoners. The monarchy created the Estates General, a limited consultative assembly that could petition the king and be consulted on fiscal policies. However, the Estates General was not a standing assembly, and it could only be convened by the king.

Early Modern or Renaissance France describes the development and dominance of absolute monarchy beginning in the 1500s, until the French Revolution in 1789. The state-building hallmarks of French absolutism like a professional army and bureaucracy, a centralized tax system, and a successful mercantilist economy evolved over many years, driven by financial exigencies, internal and religious conflicts, and territorial expansion. This period saw the addition of eastern and southern border territories that were autonomous or part of the Holy Roman Empire and the Spanish kingdoms of Aragon and Navarre. This era’s territorial expansion is the basis of the borders of France today. France also engaged in several European wars including the Italian Wars (1494-1559) and the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648) as well as internal Wars of Religion (1562-1629) between French Catholics and Protestants. The costs of war and maintaining territorial control led to financial pressures that required more efficient tax collection and the collection of fees for holding state positions, even prompting the creation of new offices for purposes of royal revenue. The taille, a land tax on peasants and commoners was a key source of royal finances but there were many other national taxes including the gabelle, a tax on salt. Administrative consolidation and control also required that feudal personal patronage systems be replaced by state-centric institutions like the intendancy system, with local level royal representatives and the regional parlements, staffed by noblesse de robe, hereditary or purchased judicial offices. Administrative and tax expansion moved power to the center and away from local nobles.

The reign of Louis XIV (1643-1715) represents the height of unconstrained absolute monarchy with the lavish transformation of the Palace of Versailles, which became the seat of French government and the royal court, and the waging of expensive wars in addition to further colonial expansion primarily in the Americas, the Caribbean, and India with some outposts in Africa, which started with Francis I (1494-1547). Notably, while the influence of the Estates General waxed and waned during the ancien régime, Louis XIV never once convened the Estates General. By the start of Louis XVI’s reign (1774-1792), the debts of war and court expenses tested the monarchy’s unchecked political power. To secure more funding and to increase popular support, Louis XVI convened the Estates General. Historically, each estate had one vote, allowing the First and Second Estate to overrule the Third Estate, which was the only estate subject to the taille. King Louis XIV initially resisted when the Third Estate called for one single National Assembly, which would be dominated by the more numerous members of the Third Estate but then capitulated when faced with demonstrations and civil unrest. With rising food prices and popular discontent with the aristocracy, Parisians seized control of the Bastille, a fortress turned royal prison that was used by Louis XIV to jail his enemies, including the political opposition. The storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789, sparked the French Revolution. Although the French Revolution ended the ancien régime, royal absolutism made several important contributions in making the modern nation-state in France through state-led lawmaking and law enforcement, war-making and national defense, money raising through taxation systems, and the growth of a professional bureaucracy.

1.2: The French Revolution and the Napoleonic France (1789-1815)

After the storming of the Bastille in 1789, the National Assembly effectively governed France and it made sweeping reforms that abolished feudalism, established state control over the French Catholic Church, suspended the parlements, drafted a new constitution, and issued the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen outlined the universality of natural human rights regardless of noble birth or faith, which included individual rights to property, freedom and life, with equal protection by law. This statement of principles remains today in the constitutions of the French Fifth Republic (1958-present). The revolution also promoted the separation of church and state, a national identity, and rational bureaucratic rule where public offices, judicial roles, and taxation laws no longer depended solely on noble birth and religious privileges. For example, a lasting legacy of the National Assembly was the complete redesign of French administrative organization to standardized administrative départements or departments of similar size with the same sub-administrative institutions and locally elected officials. Départements, which are still used today, created uniform administrative standards while also integrating these subnational units into the still powerful centralized state. Over the next three years, the National Assembly continued to make legislative and judicial reforms and create new state institutions, including a short-lived unicameral legislative branch of elected representatives, the Legislative Assembly and replacing the regional parlements with an independent judiciary. However, food shortages and economic depression, along with military defeats, exacerbated political and social divisions and led to popular revolts and the abolishment of the monarchy in 1792.

The Legislative Assembly called for the formation of the National Convention, which was tasked to create a new Constitution without the monarchy. The National Convention established the First Republic (1792–1795). The National Convention was also the first French legislative body that allowed male suffrage without class-based eligibility restrictions. However, the moderates were squeezed both by conservatives with ties to the monarchy and clergy and radical secular republicans. The National Convention, which had to contend with civil unrest and food riots due to shortage and high prices as well as ongoing war efforts, delegated increasing governance powers to the Committee of Public Safety. With the 1793 insurrection, the Jacobins, a radical anticlerical militant faction seized control of the Committee of Public Safety, suspended the constitution, and began executing enemies of the Republic by guillotine. The Reign of Terror was a year-long period of state-sanctioned violence, with a series of mass killings and public executions including those on the political right: clergy, nobles, and King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette. However, it also grew to target those in opposition and finally ended with the execution of Maximilien Robespierre, leader of the Jacobins, as the revolution turned on the Jacobin dictatorship.

Weakened in the aftermath of the Reign of Terror, the Committee of Public Safety was replaced by the Directory (1795–1799) led by moderates, which was established by the new 1795 Constitution. Facing internal and external pressures, the Directory was overthrown in a coup led by Napoleon Bonaparte, which marked the end of the French Revolution. Napoleon Bonaparte was appointed First Consul in the new more autocratic but nominally republican government, the Consulate (1799–1804). Under a new Constitution, the Constitution of the Year VIII, Napoleon Bonaparte consolidated his power into a one-man dictatorship. He established a merit-based civil service open to all classes with new elite schools to train new civil servants. In 1804, the Consulate established the Napoleonic Code, a unified legal system with many of its elements still used in France today. The Napoleonic Code kept many revolutionary principles like the rule of law, due process, rights of the accused, the separation of church and state, and the freedom of religion, but also reinstated the pre-revolutionary patriarchal control of man over his wife and children and removed divorce by mutual consent.

In 1804, France returned to absolutism with the founding of the First French Empire as Napoleon Bonaparte took the title of Emperor by popular referendum. Napoleon Bonaparte’s successes in war expanded France’s borders east and west, through the annexation of Tuscany, Piedmont, Genoa, and the Rhineland, and the placement of relatives onto the thrones of Holland, Westphalia, Italy, Spain, and Warsaw. Moreover, with allies in Austria and Germany, Napoleon’s Grand Empire spanned much of the European continent, allowing him to wage economic warfare against the British through blockades, known as the Continental System. After a decade of rule, in 1814, Napoleon abdicated following a series of military defeats and his short return from exile ended with his final defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. Following Napoleon’s final exile in 1815, a constitutional monarchy was restored as Louis XVIII returned to France as the King, with a new constitution, the Charter of 1814 ending the First Empire. King Charles X, who followed Louis XVIII, abdicated the throne after the 1830 Revolution. Then the 1848 Revolution, during which King Louis-Phillippe abdicated the throne, led to the establishment of the Second Republic with the election of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte as President. With the Coup of 1851, Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte proclaimed himself Emperor Napoleon III in 1852, founding the Second Empire (1852-1870). Under Emperor Napoleon III, France began to rebuild its colonial empire, which it had mostly lost by the French Revolution, expanding into Africa and Southeast Asia. The Second Empire ended with the capture of Napoleon III and French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871).

1.3: Third and Fourth Republic (1870-1940 and 1946-1958)

The Third Republic started as a provisional government that considered a return to monarchy but established a parliamentary republic with the 1875 Constitution, which included a bicameral parliament and a president. Despite the 70-year longevity of the Third Republic, which included the Belle Époque (1871-1914), a cultural golden age, it was marred by short-lived unstable governments that were weakened by the many divisions between political factions like anarchists, monarchists and many other groups in between. For example, the Paris Commune was a revolutionary municipal government of radicals that controlled Paris for two months, from March 1871 to May 1871, which ended only through French army’s intervention and repression. The centrist Democratic Republican Alliance dominated the parliament in the early 1900s, but its dominance was challenged by the liberal Radical Party, founded in 1901, creating a polarized government by the 1930s. However, a strong centralized bureaucracy managed economic and military modernization and France’s growing colonial empire, including the integration of colonies into France’s administrative and economic systems.

Following its defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, France’s main rival was Germany and France entered World War I (1914-1918) against Germany through its treaty obligations to Russia. With the entry of the United States into the war, France and its allies, the United States, Britain, and Italy, defeated Germany. Despite French victory and the return of Alsace-Lorraine to France, World War I was a war of attrition fought through trench warfare, which involved about 1.5 million French casualties. The high human cost of World War I and the effects of the Great Depression (1929-1939) exacerbated further political and social divisions and contributed to the instability of ruling coalition governments in the interwar period. The government of Bloc National, a right-wing coalition (1919-1924), was followed by the first Coalition of the Left, made of left-wing parties (1924-1926), not to be confused with a later second Coalition of the Left (1932-1934). The Popular Front, an alliance of Communists, Socialists, and Radicals narrowly won the 1936 legislative elections but lasted only a year until 1937, when centrists took back control of the government until the end of the Third Republic in 1940. The interwar period also saw the founding of the first mass conservative rightwing nationalist party, the French Social Party (PSF). The Third Republic’s weak and ineffectual governments have been attributed to this political whiplash. Despite appeasement policies, including the Munich Agreement (1938), France entered the war with the German invasion of Poland in 1939. The French government’s rapid collapse after its defeat in the Battle of France led to the Vichy regime (1940-1944), an authoritarian collaborationist government from the French right and center during German occupation. Charles de Gaulle led the Free French, an organization of the French resistance groups. He later led the formation of a provisional government with the liberation of France in 1944.

Charles de Gaulle advocated for a presidential system to address the paralysis of the Third Republic’s party-based system. However, a national referendum on the 1946 Constitution, which created the Fourth Republic (1946-1958), established a bicameral parliamentary system with proportional representation with executive power resting in the Prime Minister, and a largely symbolic President. Like the Third Republic, no single party or coalition was able to govern for long during the Fourth Republic. However, economic recovery was accelerated through the Monnet Plan, a national economic plan of modernization and industrial expansion policies, and the aid from the United States’ Marshall Plan. In addition, the creation of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) was proposed by French foreign minister Robert Schuman and French economist Jean Monnet to aid in economic reconstruction while strengthening Franco-German economic and political relations. France signed the Treaty of Paris (1951) sharing production of coal and steel between France, Italy, West Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. The Treaty of Rome (1957) established the European Economic Community (EEC), which included a gradual reduction of customs duties and a customs union with a goal of creating a common market with member states.

Despite progress with European cooperation, the Fourth Republic’s costly determination to hold onto its colonial empire eventually caused its demise. Initially, in the 1946 Constitution, colonies were given local autonomy and limited representation in French parliament. Military losses in Vietnam, led to French withdrawal in 1954. Negotiations for Tunisian and Moroccan independence were completed in 1956. The Suez Crisis (1956), which began with the Egyptian nationalization of the Suez Canal, built and operated by the concessions of the French government, ended with French withdrawal. However, France attempted to hold onto Algeria until the Algerian War of Independence (1954-1962), which turned into a French political crisis, risking civil war. The May 1958 crisis began as a coup by French military units, colonial officials and settlers in Algeria, supported by rightwing extremists and military leaders in France and Algeria, who supported Charles De Gaulle’s return to power and Gaullist principles of nationalism and a strong state. Coup leaders took control of Algiers and set up a new government. The National Assembly agreed to Charles De Gaulle’s offer to end the crisis and lead a new government with a new constitution that would create a strong executive in the President.

1.4: Fifth Republic (1958-present)

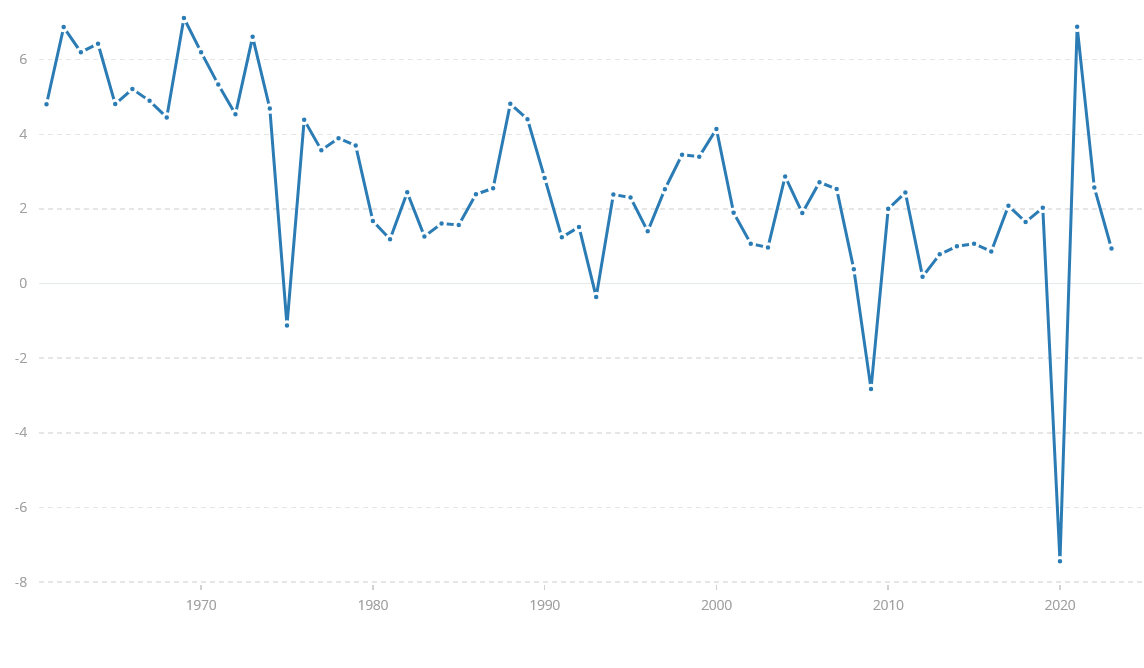

Charles De Gaulle founded the Fifth Republic in 1958 with a national referendum that supported the new constitution and the creation of a new government with a strengthened presidency under a semi-presidential system. De Gaulle was elected President in 1958, remaining the first president of the Fifth Republic until his resignation in 1969. With De Gaulle’s executive authority, his policies of national independence saw France become a nuclear power, expel NATO forces from France, promote continental European integration while vetoing British entry into the Common Market, nationalize important industries and firms, establish a welfare state, grant independence to Algeria in 1962 and many other remaining colonies, and provide military and economic aid to its former colonies to foster a French-speaking bloc in international relations. By 1968, French students, who did not have the experiences of World War II, participated in protests across universities that spread to workers and factories across France. These protests called for educational reforms and improved wages and working conditions, but the movement stalled as various factions emerged and enthusiasm waned. While he survived the protests with his party’s 1968 re-election to a majority in the National Assembly, in 1969, De Gaulle called for a referendum on constitutional reforms and resigned when they failed. Despite De Gaulle’s exit, the Fifth Republic remains to the present day. Powerful presidents from conservative to socialist have continued to lead a strong centralized state. However, since the 2000s, an increasingly divided parliament and the rise of the right, along with a sluggish economy and growing budget deficit, and concerns about immigration have produced an enduring political malaise. The unease over what direction France should take has impacted the 2007 election of conservative Nicolas Sarkozy, the 2012 election of socialist François Hollande, and the 2024 collapse of parliament in centrist Emmanuel Macron’s second term.

Section 2: Ethnic, Religious, and Cultural Identity

French identity today is the product of centuries of state formation from its Celtic origins in Roman Gaul through the assimilation of European provinces and territories and its French-speaking former colonies and overseas territories. Assimilationist policies have their origins in the French Revolution with the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen that identified all French people as citizens of the state, which took a leading role in establishing and maintaining a national identity. The French government promoted its republican approach to assimilation toward colonized peoples in the 19th and 20th centuries by offering the rights of French citizenship to those who adopted French culture, educational systems, and language. Critics of assimilation focus on the erasure of local identities and ethnic groups and on the unrealized promise of equal rights and status for colonial subjects. The impacts of French imperialism from the colonial era have persisted through common cultural and language ties, including a formal international organization of French-speaking states, the International Organization of La Francophonie. Despite historical ties to the Catholic Church, French secularism, which also has its origins in the French Revolution, has privileged the state over religious identity. However, the shift in composition of immigrants from primarily European in origin to countries in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia has strained the long-standing subordination of ethnic and religious identity to national identity.

2.1: Ethnic and National Identity

The French state privileges national identity because of its governing principles of equality of people before the law, regardless of class, ethnicity, or race. As a result, in France, the government’s census does not collect data on ethnicity or race, with a formal ban on these demographic questions in 1978. However, the French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE) collects data on immigrants, defined as anyone of foreign nationality born outside France, including those who have acquired French citizenship. In 2021, there were 7 million immigrants living in France, comprising 10.3% of the total population of 68 million, with 2.4 million, or 37% of immigrants having acquired French citizenship (INSEE, 2024a). The proportion of immigrants from Europe, namely Portugal, Italy and Spain, continues to fall while immigrants from Africa, in particular North Africa, now make up the largest group of the immigrant population. In 2023, 3.5 million immigrants born in Africa lived in France, which represents 48% of the immigrant population in comparison to the second largest group of 2.4 million immigrants, who were born in Europe, and the third largest group of 1 million immigrants, who were born in Asia (Tanneau, 2024; Rouhban, 2024a; Rouhban, 2024b). Non-European minorities are more likely to emphasize ethno-racial identity than those with European origin, even in the second generation (McAvay & Safi, 2023). However, ethnic representation in French politics is low due to its focus on class and secularism (Tiberj & Michon, 2013).

Modern European immigration to France started in the 19th century with the Industrial Revolution and continued through post-World War II. The increase in non-European immigration began post-World War II with the disintegration of France’s colonial empire and conflicts in Vietnam and Algeria. Immigrants from non-European origin experience higher unemployment and lower wages, occupy less skilled jobs, and are twice as likely to be poor (Rouhban & Tanneau, 2023). Language barriers and discrimination have led to the marginalization of immigrants and unequal access to employment, housing, social services, and transportation. The immigrant population is also centered in the urban areas, particularly in the banlieues or suburbs of the Île-de-France, which is the Paris administrative region. The banlieues were the center of the month-long 2005 French riots that highlighted the grievances of immigrant youth, who were primarily of North African origin, that included persistent poverty, unemployment, and police harassment. Debates on immigration policy have intensified with an economic slowdown, higher unemployment rates, and the rise of the anti-immigrant far-right, who have highlighted economic and social costs as well as the threats to French identity and national security. France’s reckoning with immigration also coincides with debates on the role of religious identity, which is presented in the next section.

2.2: Religious and National Identity

France as a secular nation does not have a state religion. Laïcité or secularism is a constitutional principle enshrined in the 1958 Constitution that is rooted in the French Revolution. During the French Revolution, France was the first to emancipate its Jewish population by offering citizenship and equal rights. The foundation of laïcité is the separation of a citizen’s private life, including the free exercise of religion and public spaces in which all citizens are equal regardless of ethnic or religious identities. As a result, no religion should influence the state and the state should not recognize or fund any religion, which is enshrined in the 1905 law on the Separation of the Churches and State. The Jules Ferry laws (1881-1882) established state-funded schools, including universities that are independent from the Catholic Church. Despite legal equality under laïcité, the Dreyfus Affair (1894-1906), in which Alfred Dreyfus was wrongfully convicted of treason, highlighted issues of antisemitism and set off a political crisis between anticlerical republicans and conservative pro-military right. During World War II, the Vichy regime under the German occupation participated in the French Holocaust.

Similar to race and ethnicity, the French census does not include questions about religious affiliation because of state-led secularism. However, INSEE collects data on religious demographics. Although historically France has been a nation of Catholics and it remains the dominant religion, religious disaffiliation has increased. In 2019‑2020, 51% of the population aged 18 to 59 in France reported no religious affiliation (Drouhot et al., 2023). Islam is the second most dominant religious identity at 10% of the French population in comparison to Catholicism, the religious identity of 29% of the population, the growing category of non-Catholic Christianity at 9% of population, and Judaism at less than 1% (Drouhot et al., 2023). Immigrants from countries with a Muslim tradition from the Middle East and North Africa region are more likely to have a religious affiliation with Islam and they are more active in their practice (Drouhot et al., 2023).

France currently has one of the largest populations of Muslims in Europe and public expressions of Muslim identity like the headscarf have sparked contentious debates on the scope of free exercise of religion under laïcité. In 2004, the French government banned wearing of headscarves and religious symbols in public primary and secondary schools. An additional ban on full-face veils was passed in 2011. The state role in guaranteeing secularism is increasingly under pressure from French Muslims who believe in religious accommodation in contrast to those who believe that secularism will better integrate a growing French minority of Muslims. Anti-immigrant right-wing parties have sought to further restrict Islamic practices with the rationale of protecting French secularism and national identity and security. In 2015, the Islamic terrorist attacks, most notably at Charlie Hebdo, a weekly magazine that had published cartoons of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, further heightened religious tensions and the popularity of right-wing parties. Debates on immigration and the role of ethnic and religious identity in France have been important elements in the 2007 election of conservative Nicolas Sarkozy, the 2012 election of socialist François Hollande, and the 2022 election of centrist Emmanuel Macron. Secularism as part of French national identity has had renewed support across the left and center right. Hollande supported the ban on headscarves and Macron has signed laws that require varying levels of French language proficiency for residency permits, limit birthright citizenship for children of immigrants, and allow the government wider powers to deport immigrants with criminal records and rejected asylum seekers.

2.3: French Language and Culture

Enshrined in Article 2 of the 1958 Constitution, French is the official language of France, and the French language is the foundation of French identity. French is also the official language of 25 other states and 36 international organizations. The Académie Française, established 1635 under King Louis XIII, is the official authority on the French language and still publishes an official dictionary for the French language. The Académie Française has also opposed the state recognition of regional languages, which occurred in 2008. The French language was also a cornerstone of assimilationist policies under French colonialism to establish administrative, economic and cultural control. In 1970, the International Organization of La Francophonie was established to promote French language and support the cooperation of the global community of French-speaking people.

The French state has traditionally played a key role in advancing French language and culture through the educational, cultural, and economic policies and through state-sponsored institutions like the Académie Française, the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, and the Royal Academy of Dance. The Jules Ferry laws (1881-1882) established free, mandatory, and secular education, which further standardized the use of French language. The rise of a modern French nation state includes the centralization of politics and government but also culture, with the main centers of production in the Paris region. The cabinet-level post of Minister of Culture was created by Charles de Gaulle in 1959, and the Ministry of Culture has control of the national museums and monuments, including the National Archives.

Section 3: Political Culture and Civil Society

The French Revolution granted citizens the right to form associations, including political clubs that would later develop into political parties, and also what we would call non-governmental organizations (NGOs) today. However, Emperor Napoleon I in the First Empire and Emperor Napoleon III in the Second Empire undermined associations by requiring them to be authorized by the state, leading Alexandre de Tocqueville to characterize French civil society in the early 1800s as weak. Civil society organizations were granted legal status in 1881, the same year that the secular public education system was established by the Jules Ferry laws. Many of these early civil society organizations countered the Catholic church and religious organizations, strengthening the state against conservative and royalist opposition. The 1901 Law of Associations guaranteed freedom of association, which still is in force today, but only state approved associations have legal rights. The Vichy regime (1940-1944) banned most NGOs but they re-developed in the post-World War II period in the context of a highly centralized state.

The Fifth Republic’s dirigisme, an economic doctrine of state control of economy, investment, and regulation of important industries, meant that civil society organizations, particularly in the economic sector, have remained divided and weak (Levy, 1999). However, France is well known for its regular strikes and protests, which are often mobilized by unions and have sometimes changed government policy. The Société nationale des chemins de fer français (SNCF), the national state-owned railway company, has had at least one strike per year since 1947. From 2000-2019, France averaged 127 days not worked per 1,000 employees, with a decrease to 77 days from 2020-2023 (Vandaele, 2024). In areas like civil rights, the environment, social services, and recreation, a strong central government with an increasing number of laws have given NGOs an important role in negotiating and navigating these non-economic areas (Archambault et al, 1999; Camus, 2023). These civil society organizations in France’s third sector are primarily small, numerous, and decentralized (Archambault et al, 1999). Instead, mass protests have been the most common method to demonstrate public concerns and interests to the government.

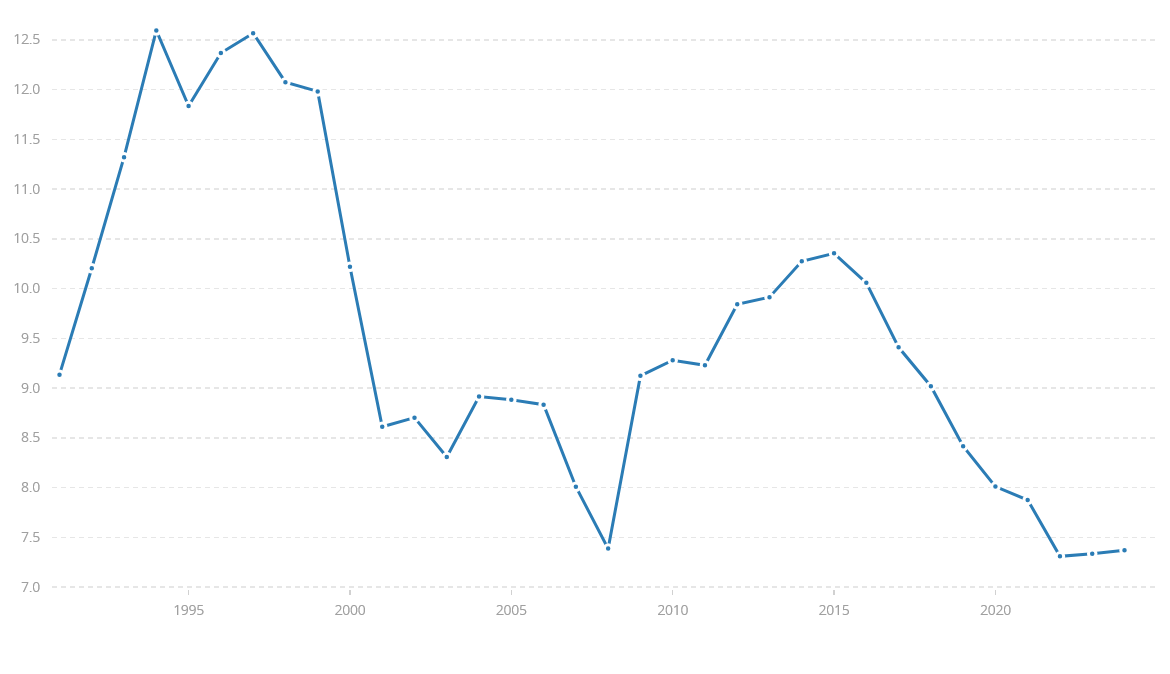

3.1: Labor Unions and Employer Federations

Despite the prevalence of strikes in France, only about 8% of the French workforce are union members, a downward trend since World War II. The Directorate of Research, Economic Studies and Statistics (DARES), the research and statistical section of the French Ministry of Labor, reports that union membership is much stronger in public sector, where around 18.7% of employees are in unions, than in the private sector at 8.4% (Pignoni, 2016). In addition, men are more likely to be union members than women, with 11.8% of male employees in comparison to 9.8% of female employees (Pignoni, 2016). Collective bargaining rules allow for unions to negotiate for all employees, not only members, and professional elections determine leadership. Unions in France are also funded primarily by the state, as well as taxes on employers. As a result, there is little incentive for rank-and-file membership. Along with the gradual decline in the industrial sector, high unemployment and job insecurity has further eroded union membership.

Shrinking membership, collective bargaining, partisan alliances, and rules that allow more than one union to represent workers in a single firm has left French labor unions in competition with one another, increasingly fragmented, and weak. A 2008 law requires a union to win at least 10% of the votes at company level to be considered representative at company level, 8% of the votes at industry level to be considered representative at industry level, and 8% of the votes at national level to be considered representative at national level. There remain five unions that are nationally representative with membership across the French economy. These five in order of size are: French Democratic Confederation of Labor (CFDT), General Confederation of Labor (CGT), General Confederation of Labor-Workers’ Force (FO), French Confederation of Christian Workers (CFTC), and French Confederation of Management-General Confederation of Executives (CFE-CGC). CFDT, which took first place from CGT in 2017, is moderate and allied with the political center. CGT has long been linked to the far left, notably the French Community Party (PCF) and still has many PCF members. FO broke from CGT due to CGT’s connection to the PCF and it remains center-left. Outside of the five national unions, there are several smaller independent unions including Fédération syndicale unitaire (FSU), which represents the French education sector.

The fragmentation and weakness of French labor unions led to the staging of mass strikes to negotiate with the government and employers, creating the paradoxical tradition of frequent general strikes and protest movements. Unions have had success in mobilizing the public against changes to their welfare benefits and pension reforms. In 2006, the French government was forced to withdraw its plans for a new employment contract for workers under the age of 26 that made it easier to fire them in the first two years of an employment contract. However, in 2010, despite protests that paralyzed France, French President Nicolas Sarkozy’s proposed reform raising the retirement age from 60 to 62 became law. The 2018 protests against a fuel tax increase sparked the large-scale Yellow Vest movement against the Macron government. Although the movement ultimately fizzled, Emmanuel Macron has faced continued protests against pension reforms, notably the 2023 protests against a law that raised the retirement age from 62 to 64.

The French business sector is organized through employer federations. French Association of Private Enterprises (AFEP) is the main lobbying group for large private sector companies. AFEP represents 118 of the largest private corporations, including Airbus and Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy. The two largest employers’ federations in France are the Movement of the Enterprises of France (MEDEF), focused on small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and the General Confederation of Small and Medium Companies (CPME), which represents small business owners. In addition, there are numerous employer federations for a single trade or industry. Employer federations have generally supported the political right, reduced taxes on businesses, economic reforms that increase flexibility in hiring and firing, and less government intervention. With many business and political leaders being énarques, graduates of the National School of Public Administration (ENA) now called the National Institute of Public Service, close relationships between the political and business class have allowed significant access points to and from the state.

3.2: Political Culture and Ideology

French political ideology has traditionally been divided along the left-right spectrum since the French Revolution. France’s multi-party system comprises a mix of conservative, social liberal, social democratic, nationalist, communist, socialist and green parties. However, the party system is fragmented, with factions even inside parties. Parties must form alliances or coalitions to govern, which have historically been organized around the center-left and center-right. However, political ideology has been less important than individual political leadership because of the populist legacies of revolution, the weakness of civil society, and the important role of the state and its executive. Moreover, the increasing importance of cross-cutting cleavages like nationalists and globalists and welfare state reformists and preservationists have led to the development and prominence of new third parties like Emmanuel Macron’s centrist Renaissance party (RE) that has rejected left and right labels. At the same time, French leaders on the left and right have a long populist tradition of appealing directly to the masses to speak for ordinary people and French identity and in opposition to established political elites. Successful populist attacks against the elitism of Macron’s government by Marine Le Pen, the leader of the far-right National Rally (NR) have contributed to electoral losses for Marcon’s Together for the Republic coalition in 2024’s European Parliament and National Assembly elections.

In addition to the populist strain in French political culture, mass protests are also a commonplace expression of French political culture. In the face of sluggish economic growth and fiscal challenges, the changing scope of French welfare system that offers healthcare, pension, and unemployment benefits have been a significant protest point, as mentioned in the previous section. Mass protests unrelated to the welfare state have included civil rights, climate change, globalization, increasing economic inequality, immigrant rights, Islamophobia, LGBT rights, racism and police brutality, and women’s rights. For example, the 2018 Yellow Vest movement coalesced around economic inequality, namely low wages and high taxes. In 2019, Black Vests protested for the rights of undocumented immigrants. The 2020 anti-racist and anti-police brutality protests, which were motivated by the global Black Lives Matters movement challenged the long-held idea of France’s colorblindness, highlighting continuing racial injustices in France.

Section 4: Political Participation

4.1: Electoral System

The electoral system in France is majoritarian with a two-round runoff for Presidential races and the National Assembly, the lower house of parliament. Presidents are elected every five years in two rounds, unless a candidate earns 50% of the vote in the first round. The second round takes place two weeks later, which is between the top two candidates. The National Assembly has 577 single member districts (SMD), in which there is one winner per district. Candidates with over 12.5% of the vote advance to a second-round winner-take-all contest, unless a candidate earns 50% of the vote in the first round. The two-round runoff system ensures that the election winner has a majority of the vote but at the cost of some disproportionality, which is typical for SMD systems. In 2022, Emmanel Macron’s Together for the Republic coalition won 39% of the second-round vote but 42% of seats in the National Assembly. While the two-round runoff system does encourage more candidates and parties than traditional SMD systems in the United Kingdom and the United States, the second-round plurality rule and the first round 12.5% threshold makes it difficult for smaller parties to win seats. The right-wing National Front, later rebranded as National Rally, won 9% of the second-round vote but 1% of seats in 2017. France’s majoritarian two round runoff system has typically produced legislative majorities. However, the 2024 snap elections called by Macron resulted in a hung parliament with huge gains by National Rally, which has led to a tenuous center-right government, already on its second Prime Minister, François Bayrou, in its first six months. The absence of a stable majority may lead to further snap elections, the first of which could occur in July 2025 ahead of the next scheduled National Assembly elections in 2029.

The Senate, the upper house of parliament, is elected indirectly by an electoral college, which includes about 150,000 regional councilors, department councilors, mayors, municipal councilors in large communes, and National Assembly members. This indirect system of electors has favored rural areas and conservatives. As a result, the Senate is typically politically oriented to the right. The leftist Socialist Party coalition won short-lived control of the Senate in September 2011, which was the first time that the Socialists had held a majority. The right bloc led by the Union for a Popular Movement (UMP) reclaimed control in 2014. There are 348 Senators representing both single-member and multi-member districts. In districts where one to two Senators are elected, the election is held in two rounds, unless a candidate receives over 50% of the vote. In districts where there are three or more Senators, the election uses proportional representation rules based on their party list order.

Campaign finance is highly regulated in France and monitored by the National Commission of Campaign Accounts and Political Financing (CNCCFP). Donations to political parties are capped at €7,500 (about $8,600) per year, and only French citizens or residents may contribute to a political party, no corporate donations. Spending limits are determined by the type of election and the public financing of parties is based on party’s vote share and seat share. For presidential elections, states reimburse 20% of spending to all parties and 50% if the candidate wins more than 5% of the total vote. The National Council on Audiovisual (CSA) regulates the coverage of election campaigns by radio and television broadcasters. Political television advertising is banned six months before an election and there is no election coverage the weekend before an election, but equal time is offered to candidates.

All voters in France are registered automatically once they reach voting age, which is eighteen years old and placed on the electoral roll. In France, electoral abstention is measured by the number of voters who abstained from voting divided by the number on the electoral roll. Abstention rates are highest in referendums and European Parliament elections and lowest in presidential elections. The abstention rates in National Assembly, regional, departmental, and municipal elections have been increasing steadily since 1959. Although the 2024 snap elections saw the highest turnout since the 1990s.

4.2: Referendums

The 1958 Constitution that established the Fifth Republic, allows for a national level referendum called by the President. National referendums under Charles de Gaulle were used to bypass government institutions like the parliament and approve contentious proposals like Algerian independence. Referendums can solidify a popular mandate but can also be risky. De Gaulle called for five referendums and when he lost the 1969 referendum about reforming the Senate, he resigned. Since de Gaulle, referendums have been used more sparingly and most notably to approve important changes in the European Union (EU). A 1972 referendum on the enlargement of the European Communities (later the EU) was approved by 68% of voters under President George Pompidou. President François Mitterrand held a 1992 referendum on the founding of the EU through the Maastricht Treaty, narrowly approved at 51%. In 2005, President Jacques Chirac lost a referendum on the European Constitution with a 55% no vote. The failure of this referendum weakened Chirac’s presidency and halted the use of referendums on the EU by later Presidents.

4.3: Local Government Elections

France is a strong unitary state with power concentrated in the national government. Decentralization efforts that began in the 1980s have increased the power of local governments but the President and the national government still control taxes, spending, and policymaking. There are three levels of local government, which are region, department, and commune. The largest grouping is regional with 27 regions, with five regions being overseas regions. The regions are led by regional councils that are elected every six years. Next, there are 101 departments, with five overseas departments, which are also classified as the five overseas regions. Departments are governed by directly elected councils. Communes are local municipalities that vary in size from cities like Paris to small villages. There are about 35,000 communes, with about 200 in overseas regions. Each commune has a mayor and a municipal council but the size and election method for the municipal council depends on the commune. National Assembly deputies and Senators can also simultaneously hold local elected positions at the region, department, and commune level with some restrictions on executive positions and multiple mandates at the same level.

4.4: Party System

In the Fifth Republic, until recently, there have been relatively stable left and right majorities that have alternated power between center-left and center-right coalitions. In the 1960s and 1970s the leftist political coalition revolved around the French Communist Party (PCF) and the French Socialist Party (PS) along with minor parties like the Radical Party of the Left (PRG). The right political bloc centered on the Rally for the Republic (RFR) and Union for a Popular Movement (UMP). Each coalition had won about half the French vote, ensuring the dominance of the two major coalitions under a SMD two round system, which necessitated coalition building to win the second round. Since the 1980s, the two-bloc system dominated by four parties has weakened with the decline of the PCF and the rise of rightwing National Rally (RN). Coalitions still organize along the left and the right, but they are no longer as independent and stable. The 2000 presidential term reduction reform to five years to match the National Assembly’s terms and the 2001 electoral calendar reform that moved parliamentary elections after presidential elections have led to the decline of cohabitation. The decreased likelihood of cohabitation, meaning divided government where the President is a different party than the majority party in parliament has shifted coalition and party building powers to Presidential campaigns and leadership. In addition, the two round runoff system allows for the development and growth of once smaller parties like RN and these smaller parties can have important roles in forming a majority coalition.

|

President Name |

Dates and Terms in Office |

Political Party |

Prime Ministers |

|

Charles de Gaulle |

1359-1969, resigned in his second term |

Union for the New Republic (UNR) |

Michel Debré (1959-1962), UNR Georges Pompidou (1962-1968), UNR Jacques-Maurice Couve de Murville (1968-1969), UNR |

|

Georges Pompidou |

1969-1974, one term, died in office |

Union of Democrats for the New Republic (UDR), replaced the Union for the New Republic |

Jacques Chaban-Delmas (1969–1972), UDR Pierre Messmer (1972-1974), UDR |

|

Valéry Giscard d’Estaing |

1974-1981, one term |

Independent Republicans (RI) and Union for French Democracy (UDI) |

Jacques Chirac (1974-1976), UDR Raymond Barre (1976-1981), RI and UDI |

|

François Mitterrand |

1981-1995, two terms |

French Socialist Party (PS) |

Pierre Mauroy (1981-1984), PS Laurent Fabius (1984-1986), PS Jacques Chirac (1986-1988), Rally for the Republic (RPR) Michel Rocard (1988-1991), PS Édith Cresson (1991-1992), PS Pierre Bérégovoy (1992-1993), PS Édouard Balladur (1993-1995), RPR |

|

Jacques Chirac |

1995-2007, two terms |

Rally for the Republic (RPR), renamed Union for a Popular Movement (UMP) |

Alain Juppé (1995-1997), RPR Lionel Jospin (1997-2002), PS Jean-Pierre Raffarin (2002-2005), UMP Dominique de Villepin (2005-2007), UMP |

|

Nicolas Sarkozy |

2007-2012, one term |

Union for a Popular Movement (UMP) |

François Fillon (2007-2012), UPM

|

|

François Hollande |

2012-2017, one term |

French Socialist Party (PS) |

Jean-Marc Ayrault (2012-2014). PS Manuel Valls (2014-2016), PS Bernard Cazeneuve (2016-2017), PS |

|

Emmanuel Macron |

2017-present, two terms |

Renaissance (RE) |

Édouard Philippe (2017-2020), Republicans (LE) Jean Castex (2020-2022), LE Élisabeth Borne (2022-2024), RE Gabriel Attal (January 2024- September 2024), RE Michel Barnier (September 2024-December 2024), LE François Bayrou (December 2024-present), Democratic Movement, center-right party |

Table 4.1: Presidents and Prime Ministers of the Fifth Republic

4.4.1: The Left

In the post-World War II period, the French Communist Party (PCF) had the largest membership and regularly won about 20% of the national vote but it was excluded from government. PCF joined the French Socialist Party (PS) in electoral alliances and was rewarded with some cabinet level positions, but PCF’s popularity gradually waned with the collapse of the Soviet Union, although it still has members from the working class and unions at the local level. Since the 1970s, the PS has been the main anchor for the French center-left and left, as the largest party of the French left. PS advocates for social democratic policies, with the state regulating a capitalist economy, including state-owned firms and a strong welfare state focused on economic equality. PS is also in favor of European integration. PS was founded in 1969 and, under the leadership of François Mitterrand, moved toward a more moderate social democratic ideology while maintaining an alliance with the PCF. PS first won power in 1981 with Mitterand’s presidential win. Mitterand held the presidency over two terms from 1981-1995 but the electoral successes of PS largely waned until the 2012 presidential election of François Hollande.

In Mitterand’s first term, he attempted to implement the 110 Propositions, a set of socialist reforms that included nationalizing banks and large industrial firms, an increase on upper level tax rates and a wealth tax, an increase in wages and layoff protections with a reduction in working hours, and an expansion of social benefits. However, instead of ushering in a period of economic recovery following the 1973 recession, exports declined, the franc lost value, and unemployment continued to rise. Mitterrand pulled back on the PS’s socialist agenda, losing the support of leftist voters and the PCF, while increasing support of the rightwing National Front (RN). PS lost its control of the National Assembly in 1986 and Mitterand named conservative Jacques Chirac as Prime Minister, who led a conservative retrenchment of socialist reforms. Cohabitation allowed Mitterrand to recover and focus instead on European integration and shift the PS toward the center.

Mitterrand was re-elected President in 1988 with a more moderate agenda that included parental leave rights and Minimum Insertion Income (RMI), which is a minimum income guarantee. The left held only a plurality in the National Assembly and not a majority in 1988 and in 1993, PS lost its fragile hold on the National Assembly due to accusations of corruption and internal factions within PS. During his second term, Mitterrand focused on furthering European integration and successfully negotiated and then convened a referendum for the ratification of the Maastricht Treaty. Facing a leadership crisis after Mitterrand, PS lost the 1996 presidential election while PS with its leftist coalition won the 1997 National Assembly election and PS leader, Lionel Jospin became Prime Minister under cohabitation with President Chirac. PS lost both the National Assembly and presidential elections in 2002 and 2007.

In 2012, PS returned to power with the presidential election of François Hollande and a PS-led majority in the National Assembly. Hollande is an énarque and a career bureaucrat that campaigned on a leftist platform that included same sex marriage, a wealth tax, stronger state regulation of the financial sector, and the lowering the retirement age. However, his agenda was stymied by continued unemployment and rising budget deficits, and he declined to run for a second term in 2017 with his historically low approval ratings. The French Green Party, rebranded as The Ecologists (LE) in 2023, has developed electoral successes in local and national elections, winning 6% of the overall vote in the 2012 legislative election. In 2012, LE signed a coalitional agreement with PS, allowing LE to form an official parliamentary group, along with the coalition’s promise to reduce nuclear energy production and cabinet level positions for LE. PS lost the presidential and National Assembly elections in 2017. The winner of the 2017 presidential election was Emmanuel Macron, a former member of PS and of Hollande’s cabinet who left to form an independent centrist party Forward! (EM), later rebranded as Renaissance (RE). PS’s 2017 presidential candidate Benoît Hamon also left PS to form a new independent leftist party, Génération.s (G.s), two months after the 2017 presidential election, in response to the decline of PS.

The 2022 presidential elections resulted in a new low with 2% of the national vote and in the 2022 legislative elections, PS joined a left-wing alliance, the New Ecologic and Social People’s Union (NUPES), which included PCF, LE, G.s, La France Insoumise (LFI), and Ensemble! (E!). NUPES won 131 seats and 32% of the vote, making it the leading opposition bloc. However, PS suspended its membership from NUPES with the refusal of LFI to denounce Hamas in 2023. In 2024, PS joined a broad left-wing coalition New Popular Front (NFP) in opposition to Marcon’s Together for the Republic coalition and the far-right National Rally (RN). In both 2022 and 2024, LFI, which was founded in 2016 by another former PS member, Jean-Luc Mélenchon won more seats than PS and in 2022, the LFI candidate, Mélenchon placed third after Macron and Marine Le Pen of RN. The 2022 and 2024 elections have illustrated the growing fragmentation of the left and the uncertain future of PS’s central role on the left.

4.4.2: The Right

Charles de Gaulle and the Union for the New Republic (UNR), which was the political party that was founded to support de Gaulle, represents the rightist tradition in the Fifth Republic and his political successors were described as Gaullists and neo-Gaullists. The right controlled the three consecutive presidencies from the founding of the Fifth Republic under de Gaulle, to Georges Pompidou and then ending with Valéry Giscard d’Estaing in 1981 with Mitterand’s victory. In the period after de Gaulle’s resignation, the right bloc centered on the Gaullist Rally for the Republic (RFR), founded by Jacques Chirac, and the center-right pro-Europe Union for a French Democracy (UDF), started by Giscard d’Estaing. The division of RFR and UMP was based less on ideology and more on personality and presidential aspirations. The Union for France, a RPR/UDF coalition, won the 1993 National Assembly election and RFR candidate Jacques Chirac won the 1995 presidential election. In 1997, a Socialist majority retook the National Assembly and the right had to make compromises for the welfare state. Chirac’s presidency faced twin challenges of slower economic growth and maintaining the welfare state illustrated by the successes of privatization and the euro but also stagnant unemployment. In 2002, Chirac, facing internal factions in the RPR that were Euroskeptics, pushed for the political right to create a single party, Union for a Popular Movement (UPM), leading to the decline of UDF. UPM, which is the largest conservative party in France, is a traditional right party that advocates for the free market and business while remaining socially conservative. In 2002, Chirac easily won the second-round runoff against Jean-Marie Le Pen of the right-wing National Front (RN), who unexpectedly took second place over Lionel Jospin of PS.

In 2007, conservative UPM candidate Nicolas Sarkozy won the presidential election on a platform of economic growth and employment as well as immigration and crime control. The Sarkozy government cut taxes, raised the retirement age to 62, cut public sector employment, and allowed employers to increase the work week. Sarkozy’s agenda was no match for the 2008 global economic crisis and the subsequent 2009 euro-zone debt crisis, which instead led to austerity measures, high unemployment, and mass protests. Sarkozy’s domestic controversies also included deportations, bans on religious headscarves, a poorly received debate on French national identity, objections to cabinet appointments, and accusations of corruption and nepotism. In 2012, Sarkozy lost his bid for a second term to leftist PS candidate François Hollande and the Socialist coalition also won control of the National Assembly. In the wake of Sarkozy’s loss, the UPM implemented primary elections that further divided the UPM along ideological lines and personal loyalties. Sarkozy returned to politics in 2014 and won the leadership of UPM, renaming it the Republicans (LR), but lost his bid to run as the Republican candidate to François Fillon. Fillon and the Republicans suffered losses in the 2017 presidential and National Assembly elections. Its fourth-place finish behind the right-wing National Rally in the 2022 legislative elections further diminished the Republican bloc.

The far-right populist National Front, now called National Rally (RN), was founded by Jean-Marie Le Pen in 1972 and it was viewed as a fringe nationalist party focused on protecting French identity, reducing immigration and deporting undocumented immigrants. RN first gained national prominence when the electoral system briefly experimented with proportional representation in the National Assembly in 1986 and it won 35 seats with 10% of the vote, ahead of PCF. The 1988 National Assembly election returned to single member districts and two round runoffs, which resulted in the RN’s loss of seats to one seat. The RN won 15% in the 1997 legislative elections but again won one seat. The 2002 presidential election’s second round runoff included the RN for the first time with Jean-Marie Le Pen losing to Jacques Chirac. From 2003-2010, RN seemed to be in decline with the UMP adopting the RN’s immigration and crime control stances. With Jean-Marie Le Pen’s daughter, Marine Le Pen’s leadership of the RN, which began in 2011, the RN’s relevance has been renewed with its push into the mainstream through a broadened agenda that includes anti-terrorism, anti-globalization, and Euroskepticism while distancing itself from its racist and xenophobic roots. Marine Le Pen came in third in the 2012 presidential election and RN established itself as the third largest party after PS and UPM in the 2012 legislative election, winning two seats in the National Assembly. In 2014, RN also won European elections with 25% of the vote, beating both PS and UPM. Mirroring her father’s 2002 presidential run, in 2017, Marine Le Pen lost against Emmanuel Macron in the second round run off. Making gains in the 2024 European parliamentary elections, RN won the most delegates for a single party, outnumbering Macron’s Together for the Republic and the Socialist Party’s coalition, which led to Macron to call for a disastrous snap election. In the 2024 snap legislative elections, RN again came in third behind Macron’s Together for the Republic and the leftist bloc New Popular Front (NFP) but this time won 125 seats in the National Assembly. RN’s increasing popular mainstream support has solidified its place as the third largest political bloc in French politics.

|

Candidate Name |

Political Party |

Vote Share |

|

Emmanuel Macron |

Renaissance (RE) |

27.85% (9,783,058 votes) |

|

Marine Le Pen |

National Rally (RN) |

23.15% (8,133,828 votes) |

|

Jean-Luc Mélenchon |

La France Insoumise (LFI), left-wing |

21.95% (7,712,520 votes) |

|

Éric Zemmour |

Reconquête! (REC), right-wing |

7.07% (2,485, 226 votes) |

|

Valérie Pécresse |

The Republicans (LR) |

4.78% (1,679, 001 votes) |

|

Yannick Jadot |

The Ecologists (LE) |

4.63% (1,627,853 votes) |

|

Jean Lassalle |

Résistons! (RES), center-right |

3.13% (1,101,387 votes) |

|

Fabien Roussel |

French Communist Party (PCF) |

2.28% (802, 422 votes) |

|

Nicolas Dupont-Aignan |

Debout la France (DLR), Gaullist |

2.06% (725,176 votes) |

|

Anne Hidalgo |

French Socialist Party (PS) |

1.75% (616,478 votes) |

|

Philippe Poutou |

New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) |

0.77% (268 904votes) |

|

Nathalie Arthaud |

Lutte Ouvrière (LO), Trotskyist communist party |

0.56% (197,094 votes) |

Table 4.2: 2022 Presidential Election Round 1

Source Data: Ministry of the Interior, 2022

|

Candidate Name |

Political Party |

Vote Share |

|

Emmanuel Macron |

Renaissance (RE) |

58.55% (18,768,639 votes) |

|

Marine Le Pen |

National Rally (RN) |

41.45% (13, 288, 686 votes) |

Table 4.3: 2022 Presidential Election Round 2

Source Data: Ministry of the Interior, 2022

4.4.3: The Center

The success of Emmanuel Macron and his new centrist party, Forward! (EM) in the 2017 presidential and legislative elections showcased the collapse of support for the Socialist party bloc on the left and the UPM bloc on the right. Macron’s win as the leader of a new and independent center party, EM later renamed Renaissance (RE), may also signify the beginnings of the development of a new French political center. Macron was a former member of PS but he is an énarque with a background in banking and as an economic adviser and minister under Hollande. RE is a socially progressive centrist party that advocates for a globalized free market and European integration. RE’s leadership was drawn from the younger technocrat class both from the center-right and center-left and many of RE’s candidates were young newcomers to elective office. Macron also appointed cabinet members from both the center left and right. As a centrist party, RE found support from centrist Socialists and conservatives, weakening PS and UPM, allowing for the rise of the far-right RN. Despite legislative majorities, Macron’s economic reforms sparked the Yellow Vest movement and he was not able to complete his planned agenda. Faced with the choice of Macron or Marine Le Pen, voters elected Macron in the 2022 presidential election. However, Macron’s Together for the Republic coalition successively lost votes on both the left and right in the 2022 National Assembly elections. Then in 2024, Macron’s coalition lost its plurality position to the broad left-wing coalition, New Popular Front (NFP) in snap legislative elections. The 2024 snap election did not produce the centrist victory Macron gambled on and instead created a hung parliament that necessitated concessions to parties of the right to govern. Macron and his coalition’s recent electoral losses and shift to the center-right call into question the hold of France’s new center on politics.

|

Political Party |

First Round Vote Share |

First Round Seats |

Second Round Vote Share |

Second Round Seats |

Total Number of Seats |

|

National Rally (RN) |

29.26% |

37 |

32.05% |

88 |

125 |

|

New Popular Front (NFP) |

28.06% |

32 |

25.80% |

146 |

178 |

|

Ensemble! (Macron’s coalition) |

20.04% |

2 |

24.53% |

148 |

150 |

|

The Republicans (LR) |

6.57% |

1 |

5.41% |

38 |

39 |

|

Union de l’extrême droite (far right coalition) |

3.96% |

1 |

5.00% |

16 |

17 |

|

Divers droite (miscellaneous right) |

3.60% |

2 |

3.60% |

25 |

27 |

|

Divers gauche (miscellaneous left) |

1.53% |

0 |

1.47% |

12 |

12 |

|

Regionalists |

0.97% |

0 |

1.06% |

9 |

9 |

|

Horizons, center-right |

2.06% |

0 |

0.95% |

6 |

6 |

|

Divers centre (miscellaneous center) |

1.22% |

0 |

0.65% |

6 |

6 |

|

Union of Democrats and Independents, center-right |

0.51% |

0 |

0.44% |

3 |

3 |

|

Divers (miscellaneous) |

0.45% |

0 |

0.14% |

1 |

1 |

|

The Ecologists (LE) |

0.57% |

0 |

0.14% |

1 |

1 |

|

French Socialist Party (PS) |

0.09% |

0 |

0.10% |

2 |

2 |

|

Extrême droite, far-right |

0.19% |

1 |

0.09 |

0 |

1 |

Table 4.4: 2024 Snap Election National Assembly Results

Source Data: Ministry of the Interior, 2024

Section 5: Formal Political Institutions

5.1: Constitution

The Fifth Republic was founded with the adoption of the 1958 Constitution, which is France’s sixteenth Constitution. The preamble of the 1958 constitution references the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen from 1789, and the 2005 Charter on the Environment and Article 1 declares France as a secular and democratic nation with popular sovereignty, equality before the law, regardless of origin, race, religion, and equal access to women and men in politics, and professional and social areas. The remaining Articles 2 to 89 are divided into 15 Titles. The Gaullist 1958 Constitution replaced the Fourth Republic’s pure parliamentary system of government with semi-presidentialism, in which an elected president shares executive powers with a prime minister and cabinet and serves fixed terms. France uses the premier-presidential subtype of semi-presidentialism in which the President can choose the prime minister and cabinet but only the parliament can hold the prime minister and cabinet accountable with a motion of censure, meaning a vote of no confidence. The 1958 Constitution also established a civil and criminal justice system, a Constitutional Council, an advisory Economic and Social Council, and a parliamentary High Court that has the power to impeach the President, which has yet to occur.

The constitutional amendment process allows for modifications approved by a national referendum initiated by the President or a parliamentary process guided by the president in which an amendment is adopted by both houses of parliament and then approved by a national referendum or a three-fifths majority vote in both houses of parliament. There have been 25 amendments to the 1958 Constitution, which have included the integration of European Union treaties and the 2024 right to abortion amendment. Some major changes to the 1958 Constitution are the 1962 amendment that allowed for the direct election of the president, the 2000 amendment that reduced presidential terms from seven to five, and the 2008 amendment that limited Presidents to two consecutive terms. Cohabitation, where the president and the prime minister are from different political parties, was common in the 1980s. However, the 2000 presidential term reduction amendment and the 2001 electoral calendar reform law that pushed parliamentary elections after presidential elections have led to the decline of cohabitation.

5.2: The Presidency

According to the French Constitution, the French president is directly elected for five years and appoints the Prime Minister, who proposes cabinet ministers to the President, who then appoints them. The President can also dissolve the National Assembly, the lower house of parliament and employ emergency powers in a state of emergency. In addition, the President chairs the Council of Ministers (the cabinet), enacts laws, and is the head of the armed forces. However, the President is one part of the dual executive in which the president is the head of state while the prime minister is the head of government. The exact distribution of powers between the dual executive is not specified in the 1958 Constitution. The lack of formal powers has not stopped Presidents from Charles de Gaulle to Emmanuel Macron in exerting their acquired powers through popular mandates, national referendums, and precedents set by unified governments in the early Fifth Republic, where the legislature and the President were from the same party or coalition. For example, the President’s important power to appoint Prime Ministers with legislative approval and dissolve the National Assembly has evolved into the power to remove the prime minister and cabinet members despite a legislative majority to uphold those appointments. Similarly, the president’s role as commander-in-chief of the armed forces and diplomatic role as head of state have become, in practice, control over defense and foreign policy, despite a shared responsibility over defense and foreign policy with the prime minister and cabinet ministers.

While French Presidents must enact laws, they do not directly govern according to the Constitution. The Government of France consists of the Council of Ministers, which is led by the prime minister as the head of government. The prime minister proposes the cabinet, who are appointed by the President, because while not formally part of the government, the President chairs the Council of Ministers. The prime minister and the cabinet can issue decrees and propose laws to be introduced to the National Assembly, particularly domestic policy and economic policy, which are outside the presidential domain of defense and foreign policy. However, when the president has a supporting majority in the National Assembly, they can propose legislation and dictate all types of policy through their control over the prime minister. Additionally, from the Constitution, the President has a suspensive veto, meaning they can ask the parliament to reconsider a law and through the prime minister, they can enact a law unless the National Assembly passes an absolute majority vote of no confidence, which has been rare, occurring twice in 1962 and in 2024. Macron used this constitutional power in 2023, when he enacted a law raising the retirement age to 64 without a vote in the National Assembly.

The President does not have unlimited executive power. When a national referendum failed, de Gaulle resigned. Under cohabitation, the president typically appoints a prime minister from the same political party or coalition as the legislative majority to avoid the risk of a parliamentary motion of no-confidence. During cohabitation, the president usually focuses on defense and foreign policy, while the prime minister takes control of domestic policy and economic policy. While cohabitation is less likely since the 2000 reform making presidential terms the same as parliamentary terms, in 2022, Macron’s coalition did not have a majority in the National Assembly. Then in 2024, Macron was further weakened as he faced a hung parliament after he called snap elections, and the National Assembly passed a no confidence vote in his short-lived center-right government.

5.3: The Government of France: Prime Minister and Council of Ministers

The Government of France includes the prime minister and the Council of Ministers. The prime minister is appointed by the president but must have the majority support of the National Assembly. The prime minister is the formal head of the Council of Ministers and proposes the Council of Ministers to the President. However, the President presides over the Council of Ministers and can appoint and remove cabinet ministers. Unlike parliamentary systems, the prime minister and the cabinet cannot serve as members of the legislature at the same time. This separation between the legislature and the prime minister and the cabinet, also links the prime minister and the cabinet more closely with the president. When the president has majority support in the National Assembly, the prime minister can easily be replaced, and the prime minister takes a secondary role in supporting the president’s agenda in the legislature. Similarly, the Council of Ministers can also be subordinate to the President’s agenda in their role of writing and proposing bills to the National Assembly when the President has the support of the National Assembly. Prime ministers can be removed by a vote of no confidence in the National Assembly, which has only occurred twice, in 1962 and 2024. While cohabitation has waned since 2000, split ticket voting between the president and the legislature could emerge again to produce cohabitation. In 2022, Macron won re-election but his political coalition garnered only a plurality. Then in 2024, Macron’s coalition lost that plurality leading him to appoint conservative Michel Barnier of the LR party as prime minister for a short lived three months, from September 2024 to December 2024, until a successful no confidence vote in the National Assembly.

5.4: The Legislature: National Assembly and the Senate

The French Parliament is bicameral with the Senate as the upper house and the National Assembly as the lower house. The 577 deputies of the National Assembly are directly elected for five-year terms from single-member districts and the 348 Senators are elected for six-year terms through indirect elections. The jurisdiction of the legislature is outlined in Article 34 of the 1958 Constitution and includes civil liberties and rights, nationality, civil and criminal law, fiscal laws, electoral law, labor laws, property rights, nationalization and privatization of businesses, and the budget. The government is responsible for all other remaining areas and for the application of all laws. For the most part, the French parliament is constitutionally designed to be weaker than the dual executive, with the National Assembly having more political power than the Senate. The National Assembly has the sole power to pass a vote of no confidence, which then forces the government to resign. The French president also has the converse power, to call snap elections and dissolve the National Assembly. If the National Assembly and the Senate cannot agree on a bill, the final decision rests with the National Assembly, whose majority will determine the bill’s fate. Most bills can pass through either house first, but finance or social security financing bills must start in the National Assembly. The National Assembly also has the power to question the government both by writing and orally, which is done weekly on Wednesday and aired publicly.