6 CHAPTER 6: USING DOCUMENTATION AND ASSESSMENT TO COMMUNICATE WITH FAMILIES

Chapter Preview

- Documentation Boards

- Portfolios

- Assessing Children’s Development

- Family Conferences

Introduction

From the moment a child walks into their classroom, they are learning. They are learning from their peers, their teachers, their families and through their own trials, errors and explorations. How can we best communicate what children are learning to their families in a respectful and reassuring manner? How can we convey that a child’s academic progress is just one aspect, as we strive to develop the whole child? In this chapter, we will discuss how intentional teachers use documentation and assessment to effectively communicate with families. The goal of this final chapter is to demonstrate how we connect observation, documentation and assessment all together to provide quality learning experiences for the children and families that we serve, and that there is value in everything we do as intentional teachers.

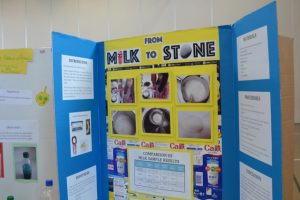

Documentation Boards: Not Just for Displaying Art

When you walk into a classroom what do you typically see on the walls? Quite possibly you will see colorful posters, charts, family photos, and lots and lots of artwork. Have you ever wondered why we post things on our walls? Is it to make our classrooms more aesthetically pleasing? More colorful and eye-appealing? Do we want to motivate our children to do their best work because it will be posted for all to see? Are we trying to create a cozy space where our children can feel comfortable and feel like they belong? Are we hoping our parents see all the great work that we are doing? Everything that is posted on your classroom walls should communicate a message. Documentation Boards help us to convey important messages. A central message that I believe to be most important is that “Children Learn Through Play!”

When parents drop off and pick up their child, they may see their child playing with blocks, puzzles, playdough, or in the dramatic play area with their peers. To some, this type of open exploration or child-directed play (sometimes called free play) may look frivolous, inconsequential or perhaps trivial because it lacks formal instruction. The idea that learning can be playful, and fun may be difficult for some parents to understand. Many parents like to see some type of tangible evidence – for example, a finished worksheet or completed art project, to “know” that teaching and learning are happening. Thus, it is necessary for us as intentional teachers to convey the importance of play through formal documentation. We must provide parents with information that explains not only the end result,(or product) but the process of how curriculum activities are specifically designed to help children master milestones in all the developmental domains. More importantly, we must showcase that learning is a direct product of play.

What are Documentation Boards

Documentation boards use observations and assessments to illustrate a child’s process of learning. When used effectively, documentation boards highlight the purpose of an activity and record the milestones that have been mastered (NAEYC, 2008). In order for parents to truly understand that children learn through play, documentation boards should include work samples or photos that highlight what the child did during the activity, along with several quotes to highlight the child’s thought process. When done correctly, teachers and families should be able to follow a child’s progress over time. Documentation Boards help teachers and families understand, without explanation, the child’s abilities and Interests. Documentation Boards provide clear evidence as to what children are learning throughout the school year in each of the developmental domains: Physical, Cognitive, Social, Emotional and Language.

What to Document

When I was a “young” teacher, I often felt obligated to post one piece of artwork for each child in the classroom so as to be “fair” that each child was represented. On my classroom walls, I mostly posted artwork and I didn’t provide any caption or describe the purpose of the activity. Not only did that take a lot of time, but it also took up a lot of wall space. As I became more intentional (and a more “seasoned” teacher, I learned that there was a more efficient way to showcase children’s learning. I began to use documentation boards to make learning more visible. Since learning is happening all day – every day in the classroom, there are a variety of topics that can be presented. Documentation boards can illustrate something as simple as a child playing with sand and water for an hour, or something complex like a child learning how to tie their shoes over a long period of time. These boards can feature one child, a group of children, or the whole class. Here are some suggested topics to consider when creating a formal Documentation Board: daily routines, project-based activities, child-directed play and exploration, outdoor play experiences, circle-time conversations, developmental milestones, social relationships, and teacher-directed lesson plan activities. The topics are endless.

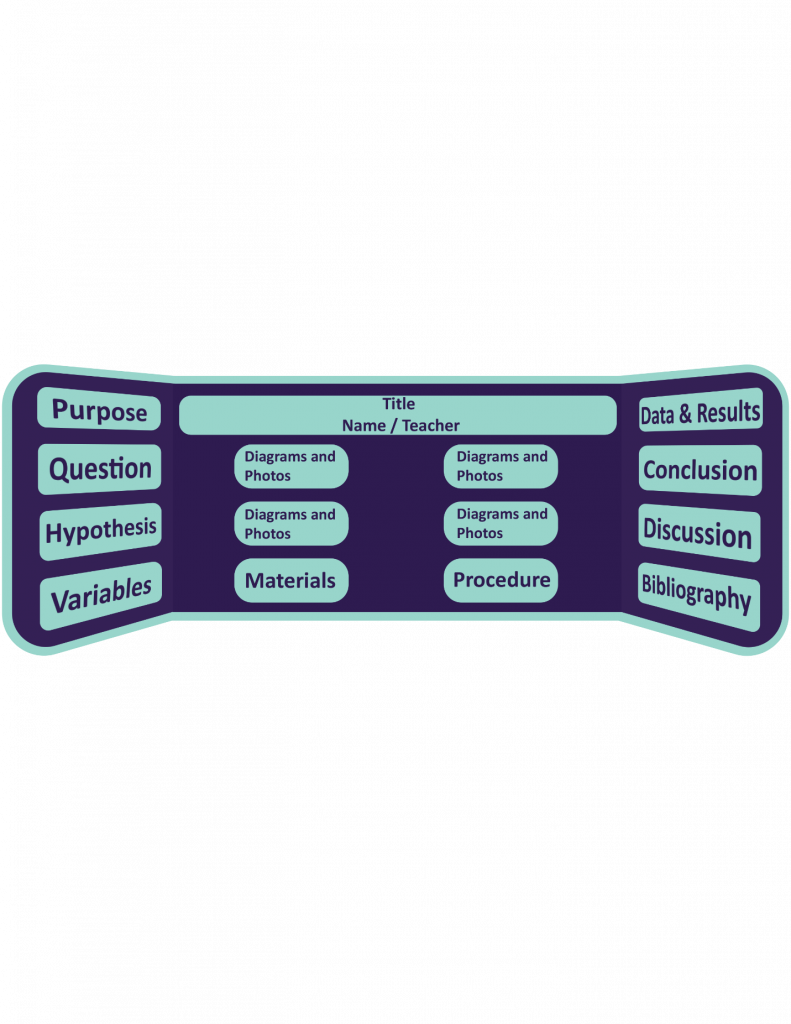

How to Make a Documentation Board

Posters, bulletin boards, and slide shows are all commonly used to create documentation boards. The format chosen to use for the documentation board should be reflective of the purpose, the audience, and the activity being presented. These boards can be simple, artistic, or even three dimensional. Before creating the board, consider the collaboration of additional teachers, children, and families. Having a team create the board adds a new level of depth, with various ideas and opinions. The first step is creating a title that invites families to approach the board. Next, mention the developmental milestones and goals for the activity (what the children are learning). Add photos and children’s quotes (both parents and children enjoy this), Include the steps that were taken or the process, and work samples as the final product. An extra step would be to add a recipe card or take-home handout so parents can replicate the activity at home. While constructing the board ask yourself, is this showing the child’s thought process, developmental growth, and both the child’s and teacher’s reflection. When creating your documentation boards remember that these boards respect all children’s work. The board needs to value efficiency over cuteness, and engagement over entertainment. (The Compass School, 2018). Lastly, the Documentation Board replaces the concept there needs to be one piece of artwork for each child in the class. When you post several documentation boards, all with different themes and purposes, you will no doubt capture all of the children in your care.

Make a decision on what you want to communicate on the documentation board:

- Projects or themes

- Special events

- Specific curriculum areas

- Learning environments

- Skill acquisition

- Child development

Collect materials for the panel:

- Children’s actual work or photocopies

- Observation notes / anecdotal records

- Information and quotes from books and journals

- Curriculum webs

- Quotes and dictation from children and teachers

- Photographs – various sizes (enlarge or shrink on a photocopier) – color, or black and white.

Select the best items that represent the idea or theme of your panel:

- Write an educational Caption for each piece

- Use a type size large enough to be read from a distance

Layout of panel:

- Determine where the panel will be displayed (on a table or wall?)

- Select a type of panel: poster board (best for wall) or three side3d board

- Title the panel

- Select a strong image as the focal point on the panel

- Aesthetics are important

- o Matte work and photographs

- o Use colored paper to support, not detract from, the images

The Perks of Using Portfolios

Another popular form of documentation is portfolios. Many programs use a portfolio system to record and store information about each child’s learning, growth and development. Using both formal and informal observations, teachers begin collecting “evidence” within the first month of a child starting school. Throughout the school year, intentional teachers collect numerous work samples, anecdotal notes, learning stories, checklists, and frequency counts, and it is necessary to safely store everything in an organized manner. A portfolio is the most optimal way to do that. A portfolio helps teachers store observation notes, pieces of art, and photos that are needed to capture and highlight a child’s individual strengths, interests and abilities. Portfolios can also store information about a child’s thought process, behavior, social interactions, and needs. With all the stored documentation, teachers can assess a child’s development.

Portfolios, like documentation boards, record and track a child’s development. More specifically, a portfolio tells the unique story of each child’s individual progress over time. Although portfolios are not designed to be an assessment tool, portfolios can be shared with families during a conference to showcase evidence of a child’s learning throughout the school year. Portfolios hold authentic samples and highlight a child’s capabilities, achievements, and progress. During a conference, rather than receiving a handout with checked boxes that rate a child’s level of learning, parents and family members will enjoy seeing first-hand what their child “can do.” Having both a formal assessment and authentic work samples provides teachers and families a clear picture of the whole child’s development.

Since learning and development are ongoing, portfolios have to be easy to use and accessible. Teachers will have to find a rhythm and medium that works best for their teaching style. Here are just a few examples of some portfolios:

- Electronic or e-portfolios stored on computers;

- Accordion files

- File folders,

- Three-ring binders,

- Creative memory photo albums

No matter which style of portfolio a teacher uses, it is important to label and date all pieces of evidence that you put into your portfolio.

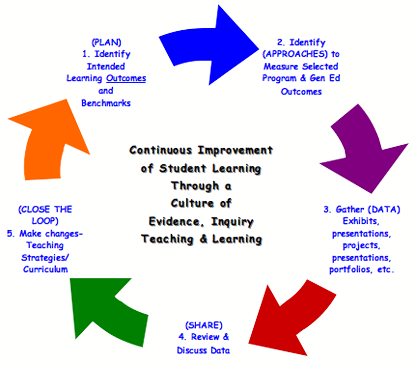

Assessing Children’s Development

Assessment is “a systematic process which allows for understanding a child’s competencies”[2] Every child in your class needs to be assessed. To properly assess children, we use observations and documentation to determine a child’s abilities, interests, strengths, and areas of development that may need additional support. The information gathered during observations guides the classroom routines, curriculum planning, and implementation to ensure quality care. Over time, assessments record a child’s learning, growth, development, and social behavior. Assessments also provide an opportunity to share information with families that will build a bridge from school to home.

Let’s take a closer look at how we might use assessments in early childhood education. First, assessment is used to inform instruction and to guide teachers as they plan curriculum. With each observation a teacher can assess children’s strengths and capabilities to determine an individualized plan of action with just the “right” balance of independent and group activities across all areas of development (e.g. social, emotional, creative, cognitive, language and physical). When teachers create meaningful curriculum based on the children’s interest and abilities, research indicates that children will take greater strides in academic learning and are more likely to be successful throughout life.

For example, a teacher may notice that one of her students has difficulty joining in and socializing with classmates during group activities. A teacher will then consider activities that would encourage peer interactions while also considering opportunities to support their independence.

Second, assessment is designed for accountability and program evaluation. Assessments provide information that is needed to evaluate program practices and to inform program policies. One of the hallmark traits of a high-quality early childhood program is the practice of continuously monitoring children’s development and responding to their learning needs. When administrators, teachers, and families reflect on program goals and outcomes they can determine specific areas that need improvement. Once areas are identified, they can focus on implementing professional development workshops and training in order to improve their ability in meeting the needs of children and families. For example, upon reviewing the math indicators for all of the kindergarten students in a school, the principal realizes that additional teacher training on math-related materials is needed to support math instruction and student learning across all of the kindergarten classrooms in the school.

Third, assessments are used to support school and family partnerships. Assessment helps teachers communicate important milestones in a child’s development to families. More importantly, when teachers share their assessments with families, there is an opportunity for teachers and parents to work together to support children as they grow. Intentional teachers respect that parents are teachers on the “home front.”

Additionally, families have valuable insight that they can contribute when assessing a child’s needs. For example, a teacher may not observe a child’s ability to identify colors but through a discussion with the parents, the teacher learns that the child identifies colors of fruit at the grocery store. In this way, parents and teachers collaborate to better understand what needs to happen in the curriculum or at home to support the child’s learning and growth.[4]

Let’s take a look at 4 Types of Assessments:

- Screening tools

- Diagnostic assessments

- Formative assessments

- Summative assessments

Screening Tools

According to developmental theories, children may not reach developmental milestones at the same time. In early care and education, we recognize that there is an “acceptable range” for children to reach developmental milestones. That being said, we also recognize that when development does not happen within an expected time frame “red flags” can be raised and teachers may have concerns about developmental disorders, health conditions, or other factors that may negatively impact the child’s development. A developmental screening is the early identification of children at risk for cognitive, motor, communication, or social-emotional delays that may interfere with expected growth, learning, and development, and may warrant further diagnosis, assessment, and evaluation. Programs may conduct the following screenings:

- Developmental screening tools include the domains of cognition, fine and gross motor skills, speech and language, and social-emotional development.

- Social-emotional screening is a component of developmental screening of young children that focuses on the early identification of possible delays in the expected development of a child’s ability to express and regulate emotions, form close and secure relationships, and explore his/her environment and learn.

- Mental health screening is the early identification of children at risk for possible mental health disorders that may interfere with expected growth, learning, or development that warrant further diagnosis, assessment, or evaluation.

It is recommended that young children receive screenings to help identify potential problems or areas needing further evaluation. By recognizing developmental issues early, children can be provided with treatment or intervention more effectively, and additional developmental delays may be prevented. Developmental screenings should begin early in a child’s life and should be conducted through third grade. Practitioners should use reliable and valid screening tools that are age-appropriate, culturally inclusive and in the home child’s language.

Developmental screenings are often universally performed on large groups of children. The results generated from this type of procedure most commonly are used by programs to identify those few children who may need to receive a more extensive or “diagnostic” assessment for determining developmental delays or special needs. Screenings are brief, and usually effective in catching the most severe cases of children who would need a follow-up evaluation. Screening tools can also be used to assess whether a child is developmentally ready to graduate or move into the next educational level, in other words – a child’s school readiness. There is controversy around whether school districts should be permitted to use readiness tests since school districts are not permitted to deny children entry to kindergarten based on the results of a readiness test. One on side there are those that believe many children are often mislabeled. Because young children can demonstrate a wide range of results based on how comfortable they are at the time of the screening, screening results can be inaccurate and children, especially dual language learners, may be placed into remedial classes or special education programs. On the other hand, some proclaim that the screening process at this point will provide young children and their families with access to a wide variety of services early on.

Diagnostic Assessments

Diagnostic assessment tools are typically standardized for a large number of children. A score is given that reflects a child’s performance related to other children of the same age (and less common gender and ethnic origin). A diagnostic assessment typically results in a diagnosis for a child. Some common diagnoses are related to intelligence, intellectual disability, autism, learning disabilities, sensory impairment (deaf, blind), or neurologic disorders. Persons administering diagnostic assessment tools must meet state and national standards, certification, or licensing requirements. Some diagnostic assessment tools used for determining or identifying developmental issues are The Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (WPPSI), the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID), electroencephalogram (EEG), Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children (K-ABC), the Battelle Developmental Inventory (BDI), and the Pre-Language Assessment Survey (PreLAS). Many other diagnostic assessment tools are available for early childhood. The Buros Institute of Mental Measurements at the University of Nebraska publishes the Buros Mental Maturity Yearbook which helps educators and other childcare professionals choose a tool that is reliable and highly regarded in the diagnostic assessment community.

Formative Assessments

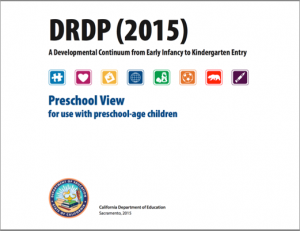

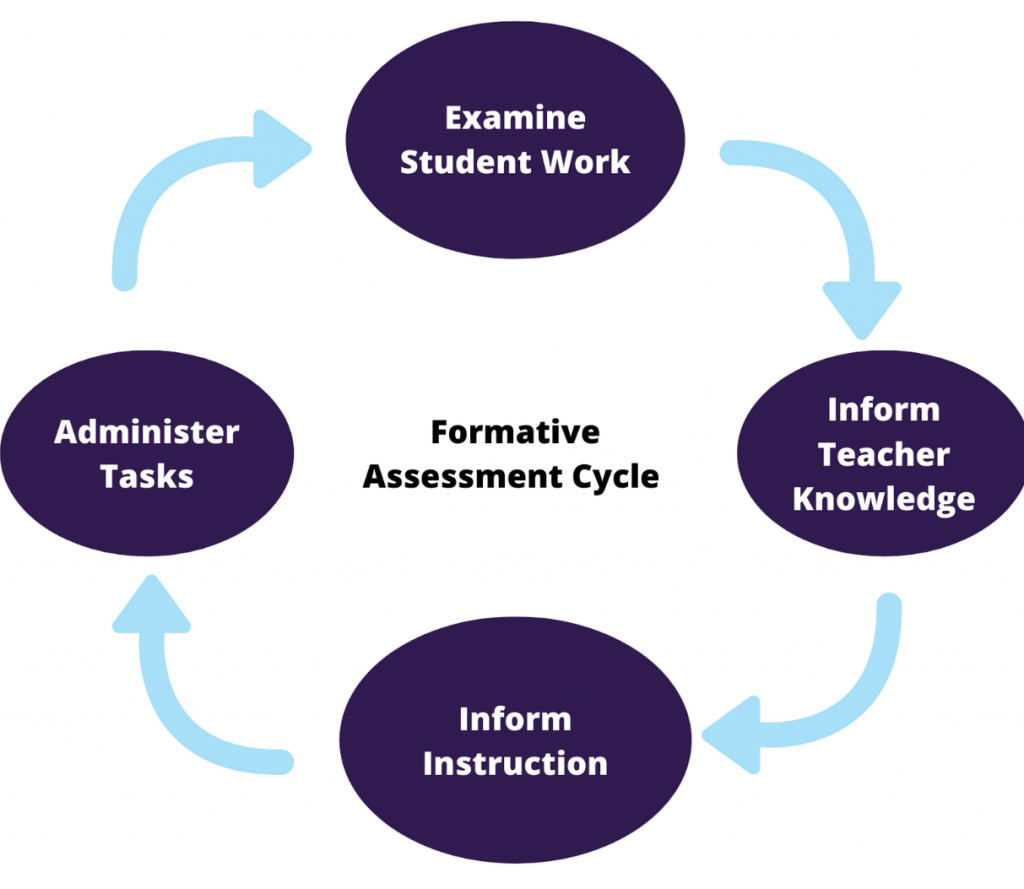

The primary purpose of the formative assessment is to gather evidence that teachers can use to inform instruction, implement learning opportunities and measure a child’s learning. As stated in previous chapters, through ongoing observations, evidence is collected and then used to measure the child’s learning. To gather an accurate account of what children are learning and how they are learning, observations should occur during daily activities and routines, and should be conducted indoor as well as outdoor. With this information, teachers make instructional adjustments to close the gap between a child’s current understanding and what the desired goals are for the child as recommended by formal assessment tools like the Desired Result Developmental Profile (DRDP).

Formative assessment can consist of formal assessments or informal assessments. Formal assessments are defined as highly valid and reliable and standardized tools that are administered in a similar manner each time for every child. These tools have standards of comparison (norm-referenced, standards-referenced, and criterion-referenced) to ensure equitable and consistent results. Such tools usually emerge from research studies published by a national company (e.g. Desired Results Developmental Profile (DRDP) or Rating Scales that are based on the acquisition of age-appropriate developmental milestones). Informal assessments, on the other hand, usually may be published, but can also be developed by a teacher or program (i.e. a classroom checklist or frequency count chart). Informal assessments often utilize observable techniques such as anecdotal notes, work samples, and video recordings. Whether formal or informal tools and techniques are used, it is important to note that assessment is not a one-time event since it is difficult to gather valid and reliable information from just one observation technique or from one tool. Formative assessments are on-going.

For best results, intentional teachers are encouraged to assess children through authentic, naturalistic observations. Such observation should be collected throughout the school year, and not just when preparing for family conferences. Another best practice, early care educators are encouraged to actively involve young children with the assessment process. Informal observations and conversations are needed to purposefully plan intentional and individualized activities. Lastly, teachers are encouraged to share learning goals with both children and parents, as well as provide opportunities for children to monitor their ongoing progress. Learning Stories are a great technique to encourage joint collaboration between teachers, families, and children.

Summative Assessments

In primary grades, summative assessment, often called high-stakes assessments, are designed to measure a child’s overall developmental progress at the end of a school year. These assessments can also be administered at certain grade levels for state or local accountability purposes (e.g. Blue-Ribbon Recognition). Summative assessments seek to measure a child’s academic performance. Scores are published and parents are notified of their child’s individual score along with their child’s percentile ranking as compared to other children who are in the same grade. In early care and education however, summative assessments essentially look back to see how effective the teacher or program is at providing high-quality care. This is form of assessment allows families, teachers and administrators to evaluate instruction practices, curriculum, and whether a child is in need of intervention or teachers are in need of professional development. These assessments help recognize whether or not the child has fallen short of, met, or exceeded the expected standards. Although the results of formative assessments are primarily of interest to teachers, families are eager to know how their child is doing socially and academically. Administrators can utilize the assessment information to identify strengths and challenges of curriculum and instruction, in order to make improvements on the next year’s program policies or procedures.

How are Assessments are Used

Planning Curriculum- Teachers use assessments to understand a child’s capabilities and needs. By focusing on what a child can do, teachers then establish individualized goals for that child. By continuing to observe and document milestones, teachers can proactively assess a child’s development and adjust the curriculum accordingly. For example, if a teacher determines that a child needs support in their fine motor development, activities that exercise the pincer grasp will be implemented.

Documentation on behavior should be considered when planning curriculum. If data shows reoccurring conflict taking place in a specific area, teachers should assess if there are enough materials and space in that area, and decide if the materials provided are age-appropriate. For example, after reviewing the data, the teachers concluded that conflict was occurring in the dramatic play area because there were not enough baby dolls for the number of children playing at the same time.

Ensuring School Readiness – Whether you use checklists or the DRDP, both assessments will collect data about milestones of development. Recording a child’s progress for each domain of development will determine school readiness. School readiness refers to children having enough knowledge and experience to succeed in a kindergarten classroom.

Adjusting the Classroom – Assessments can also be used to adjust teaching styles, classroom setups, daily schedules, and routines. When observing children, teachers should document how the class responds to certain routines, transitions, and language. For example, if the data collected shows that children are having a difficult time falling asleep during nap time, the daily schedule can be adjusted to allow more outdoor play before nap time.

Data can also show us why certain behaviors are occurring. When reviewing data, evaluate what happens before the behavior is observed, and assess what changes can be made to redirect the child. For example, if conflict and running in the classroom are occurring in the morning, the parent drop-off could be moved to the outdoor classroom to allow a large space for children to play and interact before going inside.[9]

Pin It! Further Information on Authentic Observation and Assessment

Read this article for more information on New Learnings in Early Care and Education: https://www.first5la.org/article/new-learnings-in-early-care-and-education/

· Watch this video to learn more about authentic assessment: https://www.cde.state.co.us/resultsmatter/whatisauthenticassessment-player

· Read this report from National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER) for more information on balanced preschool assessment:

· http://nieer.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/7-1.pdf

· Watch this video to learn more about Organizing for Assessment in ECE: – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hfHERCVabwE

Family Conferences

Conferences Building Family Partnerships

Once assessments have been completed, it is time to meet with a child’s family. The purpose of the conference is to share information about the child and to build a vital partnership with the child’s family. Some parents may not understand the connection between play and learning. Sharing information about play-based curriculum and how it supports development can allow parents to better understand your goals for learning and how the classroom functions. By including parents in discussion making about curriculum and assessments we can encourage support areas development outside of the classroom.

For example, if the individualized curriculum is supporting color recognition, we can suggest that families continue to support this skill by identifying produce colors at the grocery store and/or pointing to certain colors in their favorite books.

In a blog by Concordia University, Portland some key tips are suggested to ensure a successful and engaging family conference occurs:[10]

1. Offer a flexible conference schedule

Some parents have more than one child at different schools, some families may have limited transportation options and some parents may work multiple jobs which can limit their time and availability. In these cases, teachers may need to be flexible to accommodate special circumstances. Teachers can schedule conferences in the morning, later in the afternoon, or during recess breaks. If technology is available, meetings can be offered via Skype or FaceTime as an option for parents who cannot make it to school.

2. Prepare, prepare, prepare

Portfolios and assessments must be updated and organized for each child on a regular basis.

3. Arrange for a translator if needed, and find a way to connect

Parents who don’t speak English require a translator. If schools cannot arrange for a translator, family members may need to sit in on the conference, for example an older sibling or an aunt or maybe even a neighbor) — ideally not a student.

When there is a language barrier, teachers should try to find a respectful way to communicate and connect with families. As a reminder, even though families cannot fluently speak the same language, they deserve your professional approach. Try learning a few phrases in their native language to show you’re trying to connect; even “Hello,” “How are you?” and “Thank you” can go a long way.

4. Be aware of your body language and how you verbally communicate

The classroom environment speaks volumes and so does your body language and how you talk with your families. Check out your body language. Are your arms typically crossed? Do you smile or glare? How is your tone when you speak? Are you calm and reassuring, or sounding like a robot? Do you pause and allow parents to ask questions, or are you hurried and rushing through information? Are you aware and considerate of cultural backgrounds and family practices? For example, did you know that eye contact and handshaking may not be a common practice with some families?

5. Sit side-by-side

Since teachers and parents are on the same team teachers are advised to sit next to parents rather than across from them behind a desk. By arranging the furniture in a friendly and non-threatening way, teachers express their desire to build a partnership with each parent, which can diffuse unnecessary tension on both sides.

6. Share real stories and student work

Even the best teachers can’t remember all of the details they need to share with every parent. A portfolio with anecdotal notes and work samples provide parents with real insight into what’s happening in their child’s academic day.

7. Include the positive and focus on what the child CAN DO

Each student has positive traits and potential. Share at least one shining trait with parents at the beginning and another at the end of the conference. That trait could be an academic trait or a character trait, such as helpfulness, persistence, or hard work. Teachers can follow the “sandwich method” or the “glows and grows” method where you share a child’s positive achievements or traits that make them glow, in addition to providing two or more areas in which they can grow. Always end on a high note with another glowing detail or anecdote.

8. Create clear goals

Every student, even the gifted ones, can improve in some way. Write specific goals for each student. Along with those goals, create an action plan with steps for improvement, as well as a timeline. Your plan of action should include activities that will be done at school as well as activities that can be done at home. Sharing this with parents can increase buy-in since they will be able to see a clear path to success that has achievable benchmarks and goals that are part of a realistic, structured plan.

9. Avoid education jargon

Not everyone is familiar with DRDPs or diagnostic and summative assessments. Avoid overwhelming parents with education lingo. Speak in plain terms, explain what you mean, and make sure parents are clear about the information you have presented. Encourage parents to ask questions as needed for clarification.

10. Give parents responsibility

Early educators know that children do better in school when their parents are involved. A perfect way to get parents involved is to ask questions about family life and routines (a family questionnaire is ideal). Families should be encouraged to get involved throughout the school year. For example, they can be special guests, and talk about their jobs or they can read their favorite story to the children. Parents who are involved early on, will be more likely to follow through on their “plan of action” once it is presented at the conference.

11. Encourage questions

Approachable teachers build a lasting connection with parents and promote a positive learning experience with their children. Not only do you want your students to feel comfortable enough to ask questions, but you want your parents to feel they can approach you as well. Although your time may be limited during the school day, it is important to carve out some time and space to discuss important matters with parents. If parents cannot make the conference, offer your email address to allow for some time for a brief “q and a” any point during the school year. NOTE: Hitting parents up at the end of a long work day and rushing through important details regarding their child is NOT recommended.

12. Don’t make assumptions about parents or students

Avoid relying on stereotypes and allowing personal biases to cloud your judgment. View all parents as partners because, like it or not, they are. Work to make sure that even the most challenging students and parents feel like they are welcomed and a part of the team.

13. If a parent becomes hostile, don’t engage

No matter how prepared, pleasant and affirming you are, some parents may become hostile or upset while at the conference, especially if there are areas of concern or issues with a child’s challenging behavior that need to be addressed. Some parents may be used to hearing bad news, other parents don’t trust or have little regard for teachers, some parents feel a need to defend their child, while other parents may be upset about a personal matter and may take their frustration out on you. Remain calm! If possible, let the parent vent. Use active listening and really listen to the parent’s concerns. Discuss how both parties want what’s best for the child and reassure them that you have their child’s interest at heart. Look for a compromise or strategy that best supports the child and their family. Stay focused on the task at hand – the conference – and reemphasize the positive. Sometimes, a follow-up meeting may need to be scheduled.

14. Remain professional at all times

Teaching is a challenging job. Like parents, you may have an off day and you may be tempted to stray off into an unprofessional area. We also may cross some fine lines and become “friends” with our families. Here are some topics that should never be discussed with families during a conference (or at any time):

- -Speaking negatively about school administrators or other teachers.

- -Comparing two or more students to each other.

- -Discussing another student’s behavior, family, or performance.

- -Blaming parents for a child’s academic performance or behavior.

- -Arguing or becoming hostile with parents.

- -Complaining about school policies or procedures.

15. Document, document, document

Because you will meet with several families in the course of a week, it is a good idea to make notes about the conversations and outcomes of the conference. You may need to refer to them at a later time when planning a follow-up meeting, or when planning additional curriculum activities. Once in a while, a parent may notify your administrator that they have concerns about the information that was shared during the conference and your notes can be shared with your administrator to help see both sides of the conversation.

16. Stay in contact with parents

Parents should be able to get in touch with you to follow up or address new concerns. Email is the most convenient way for you to receive messages and respond to parents, but phone calls or future conferences may be necessary, too. Set the guidelines and boundaries for future communications.

According to Seplocha, teachers have many important responsibilities, especially preparing for effective and engaging parent-teacher conferences. When teachers connect with family members and establish a respectful relationship, the positive outcome provides a lifeline that will ultimately support a child’s overall development and learning.

Figure 6.9 Carol Mahn (right), a first grade teacher at the Hanscom Primary School, meets Melissa Weyand and her son, Maximas, during a “Meet and Greet”.[11]

Footnotes

[2] The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2015). Chapter 7: Knowledge and Competencies. In Transforming the Workforce for Children Birth Through Age 8: A unifying Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.nap.edu/read/19401/chapter/13

[3] Image by Rich James is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

[4] The National Education Goals Panel. (2000). Principles and Recommendations for Early Childhood Assessments. Retrieved from https://ectacenter.org/eco/assets/pdfs/NEGP_goal1_Assessment_Principles.pdf

[5] Image by Vita Marija Murenaite from Unsplash.

[8] Image by College of the Canyons ZTC Team is licensed under CC BY 4.0

[9] The National Education Goals Panel. (2000). Principles and Recommendations for Early Childhood Assessments. Retrieved from https://ectacenter.org/eco/assets/pdfs/NEGP_goal1_Assessment_Principles.pdf

Resources for Early Learning. (n.d.). Early Childhood Assessment. Retrieved from http://resourcesforearlylearning.org/fm/early-childhood-assessment/

Stipek, D. (2018). Early Childhood Education in California. Retrieved from https://gettingdowntofacts.com/sites/default/files/2018-09/GDTFII_Brief_EarlyChildhood.pdf

[10] Gunn, J. (2018). 15 Tips for Leading Productive Parent-Teacher Conferences. Retrieved from https://education.cu-portland.edu/blog/classroom-resources/parent-teacher-conferences/