12 Chapter Twelve: Basic Nutrition for Children

Chapter 12 Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

-

- Define and explain the function of each macronutrient and type of micronutrient.

- Examine factors that affect the quality of food.

- Discuss influences on food choice.

- Outline how to achieve a healthy diet.

- Describe programs that support nutrition in early care and education programs.

- Identify ways to assess the quality of meals and snacks in early care and education programs.

Licensing Regulations

Licensed child care providers must follow the Federal Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) meal plan requirements.

Introduction

In order to plan, prepare, and serve nutritious foods to children in early care and education programs it’s important to have a basic understanding of nutrition and the programs and resources available to support meeting children’s nutrition needs.

What are Nutrients?

The foods we eat contain nutrients. Nutrients are substances required by the body to perform its basic functions. Nutrients must be obtained from our diet, since the human body does not synthesize or produce them. Nutrients have one or more of three basic functions: they provide energy, contribute to body structure, and/or regulate chemical processes in the body. These basic functions allow us to detect and respond to environmental surroundings, move, excrete wastes, respire (breathe), grow, and reproduce. There are six classes of nutrients required for the body to function and maintain overall health. These are carbohydrates, fats, proteins, water, vitamins, and minerals. Foods also contain non-nutrients that may be harmful (such as natural toxins common in plant foods and additives like some dyes and preservatives) or beneficial (such as antioxidants).

Macronutrients

Nutrients that are needed in large amounts are called macronutrients. There are three classes of macronutrients: carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. These can be metabolically processed into cellular energy, allowing our bodies to conduct their basic functions. A unit of measurement of food energy is the calorie. Water is also a macronutrient in the sense that you require a large amount of it, but unlike the other macronutrients, it does not yield calories.

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates are molecules composed of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen. The major food sources of carbohydrates are grains, milk, fruits, and starchy vegetables, like potatoes. Non-starchy vegetables also contain carbohydrates, but in lesser quantities. Carbohydrates are broadly classified into two forms based on their chemical structure: simple carbohydrates, often called simple sugars; and complex carbohydrates.

Simple carbohydrates consist of one or two basic units. Examples of simple sugars include sucrose, the type of sugar you would have in a bowl on the breakfast table, and glucose, the type of sugar that circulates in your blood.

Complex carbohydrates are long chains of simple. During digestion, the body breaks down digestible complex carbohydrates to simple sugars, mostly glucose. Glucose is then transported to all our cells where it is stored, used to make energy, or used to build macromolecules. Fiber is also a complex carbohydrate, but it cannot be broken down by digestive enzymes in the human intestine. As a result, it passes through the digestive tract undigested unless the bacteria that inhabit the colon or large intestine break it down.

One gram of digestible carbohydrates yields four kilocalories of energy for the cells in the body to perform work. In addition to providing energy and serving as building blocks for bigger macromolecules, carbohydrates are essential for proper functioning of the nervous system, heart, and kidneys. As mentioned, glucose can be stored in the body for future use.

Fats

Fat (officially called lipids) are also a family of molecules composed of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, but unlike carbohydrates, they are insoluble in water. Fats are found predominantly in butter, oils, meats, dairy products, nuts, and seeds, and in many processed foods. The main job of fats is to provide or store energy. Fats provide more energy per gram than carbohydrates (nine kilocalories per gram of fats versus four kilocalories per gram of carbohydrates). In addition to energy storage, fats serve as a major component of cell membranes, surround and protect organs (in fat-storing tissues), provide insulation to aid in temperature regulation, and regulate many other functions in the body.

Proteins

Proteins are macromolecules composed of chains of subunits called amino acids. Amino acids are simple subunits composed of carbon, oxygen, hydrogen, and nitrogen. Food sources of proteins include meats, dairy products, seafood, and a variety of different plant-based foods, most notably soy. The word protein comes from a Greek word meaning “of primary importance,” which is an apt description of these macronutrients; they are also known colloquially as the “workhorses” of life. Proteins provide four kilocalories of energy per gram; however providing energy is not protein’s most important function. Proteins provide structure to bones, muscles and skin, and play a role in conducting most of the chemical reactions that take place in the body. Scientists estimate that more than one-hundred thousand different proteins exist within the human body. The genetic codes in DNA are basically protein recipes that determine the order in which 20 different amino acids are bound together to make thousands of specific proteins.

Water

There is one other nutrient that we must have in large quantities: water. Water does not contain carbon, but is composed of two hydrogens and one oxygen per molecule of water. More than 60 percent of your total body weight is water. Without it, nothing could be transported in or out of the body, chemical reactions would not occur, organs would not be cushioned, and body temperature would fluctuate widely.

|

Protein |

Carbohydrates |

Fats |

Water |

Figure 12.1 – The Macronutrients: Carbohydrates, Fats, Protein, and Water[1]

Micronutrients

Micronutrients are nutrients required by the body in lesser amounts, but are still essential for carrying out bodily functions. Micronutrients include all the essential minerals and vitamins. There are sixteen essential minerals and thirteen vitamins (See Table 12.1 “Minerals and Their Major Functions” and Table 12.2 “Vitamins and Their Major Functions” for a complete list and their major functions). In contrast to carbohydrates, fats, and proteins, micronutrients are not sources of energy (calories), but they assist in the process as components of enzymes. Enzymes are proteins that cause chemical reactions in the body and are involved in all aspects of body functions from producing energy, to digesting nutrients, to building macromolecules. Micronutrients play many essential roles in the body.

Minerals

Minerals are solid inorganic substances that form crystals and are classified depending on how much of them we need. Trace minerals, such as molybdenum, selenium, zinc, iron, and iodine, are only required in a few milligrams or less. Macrominerals, such as calcium, magnesium, potassium, sodium, and phosphorus, are required in hundreds of milligrams. Many minerals are critical for enzyme function, others are used to maintain fluid balance, build bone tissue, synthesize hormones, transmit nerve impulses, contract and relax muscles, and protect against harmful free radicals in the body that can cause health problems such as cancer.

Table 12.1 – Minerals and Their Major Functions [2]

| Major Mineral | Major Function |

| Sodium | Fluid balance, nerve transmission, muscle contraction |

| Chloride | Fluid balance, stomach acid production |

| Potassium | Fluid balance, nerve transmission, muscle contraction |

| Calcium | Bone and teeth health maintenance, nerve transmission, muscle contraction, blood clotting |

| Phosphorus | Bone and teeth health maintenance, acid-base balance |

| Magnesium | Protein production, nerve transmission, muscle contraction |

| Sulfur | Protein production |

Trace Minerals and their Major Functions

| Trace Mineral | Major Function |

| Iron | Carries oxygen, assists in energy production |

| Zinc | Protein and DNA production, wound healing, growth, immune system function |

| Iodine | Thyroid hormone production, growth, metabolism |

| Selenium | Antioxidant |

| Copper | Coenzyme, iron metabolism |

| Manganese | Coenzyme |

| Fluoride | Bone and teeth health maintenance, tooth decay prevention |

| Chromium | Assists insulin in glucose metabolism |

| Molybdenum | Coenzyme |

Vitamins

The thirteen vitamins are categorized as either water-soluble or fat-soluble. The water-soluble vitamins are vitamin C and all the B vitamins, which include thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, pantothenic acid, pyridoxine, biotin, folate and cobalamin. Unneeded water soluble vitamins are excreted from the body. The fat-soluble vitamins are A, D, E, and K. Vitamins are required to perform many functions in the body such as making red blood cells, synthesizing bone tissue, and playing a role in normal vision, nervous system function, and immune system function. Fat soluble vitamins are stored in the body in fat (and can become toxic when too much is consumed, almost always from supplements).

Table 12.2 – Vitamins and Their Major Functions [3]

Water Soluble

| Vitamin | Major Function |

| Thiamin (B1) | Coenzyme, energy metabolism assistance |

| Riboflavin (B2 ) | Coenzyme, energy metabolism assistance |

| Niacin (B3) | Coenzyme, energy metabolism assistance |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | Coenzyme, energy metabolism assistance |

| Pyridoxine (B6) | Coenzyme, amino acid synthesis assistance |

| Biotin (B7) | Coenzyme, amino acid and fatty acid metabolism |

| Folate (B9) | Coenzyme, essential for growth |

| Cobalamin (B12) | Coenzyme, red blood cell synthesis |

| C (ascorbic acid) | Collagen synthesis, antioxidant |

Fat Soluble

| Vitamin | Major Function |

| A | Vision, reproduction, immune system function |

| D | Bone and teeth health maintenance, immune system function |

| E | Antioxidant, cell membrane protection |

| K | Bone and teeth health maintenance, blood clotting |

Vitamin deficiencies can cause severe health problems and even death. Some vitamins have been found to prevent certain disorders and diseases such as scurvy (vitamin C), night blindness (vitamin A), and rickets (vitamin D).[4]

Table 12.3 – Summary of the Functions of Nutrients [5]

| Name of Nutrient | Description of Function |

| Protein | Necessary for tissue formation, cell reparation, and hormone and enzyme production. It is essential for building strong muscles and a healthy immune system. |

| Carbohydrates | Provide a ready source of energy for the body and provide structural constituents for the formation of cells. |

| Fat | Provides stored energy for the body, functions as structural components of cells and also as signaling molecules for proper cellular communication. It provides insulation to vital organs and works to maintain body temperature. |

| Vitamins | Regulate body processes and promote normal body-system functions. |

| Minerals | Regulate body processes, are necessary for proper cellular function, and comprise body tissue. |

| Water | Transports essential nutrients to all body parts, transports waste products for disposal, and aids with body temperature maintenance. |

Quality of Food

One measurement of food quality is the amount of nutrients it contains relative to the amount of energy it provides. High-quality foods are nutrient dense, meaning they contain significant amounts of one or more essential nutrients relative to the amount of calories they provide. Nutrient-dense foods are the opposite of “empty-calorie” foods such as carbonated sugary soft drinks, which provide many calories and very little, if any, other nutrients. Food quality is additionally associated with its taste, texture, appearance, microbial content, and how much consumers like it. [6]

Food: A Better Source of Nutrients

It is better to get all your micronutrients from the foods you eat as opposed to from supplements. Supplements contain only what is listed on the label, but foods contain many more macronutrients, micronutrients, and other chemicals, like antioxidants, that benefit health. While vitamins, multivitamins, and supplements are a $20 billion industry in the United States, and more than 50 percent of Americans purchase and use them daily, there is no consistent evidence that they are better than food in promoting health and preventing disease.[7]

Food Additives

People have been using food additives for thousands of years, but certainly not to the level that are used today in the typical American diet. Today more than 3000 substances are used as food additives. Salt, sugar, and corn syrup are by far the most widely used additives in food in this country. How this might affect the quality (including nutritional value) of food will depend on the additive and the person’s individual risk factors such as allergies, intolerances, etc.

Figure 12.2 – Food Additives

Salt[8] |

Sugar[9] |

Food coloring[10] |

“Food additive” is defined by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as any substance that—directly or indirectly—becomes a component or otherwise affects the characteristics of any food. This definition includes any substance used in the production, processing, treatment, packaging, transportation or storage of food.

Additives are used to maintain or improve safety, freshness, nutritional value, taste, texture and appearance. The use of food additives has become more prominent in recent years due to the increased production of prepared, processed, and convenience foods.

According to the FDA, “Direct food additives are those that are added to a food for a specific purpose in that food.” For example, using phosphates in meat and poultry products to retain moisture and protect the flavor.

“Indirect food additives are those that become part of the food in trace amounts due to its packaging, storage or other handling,” according to the FDA. For instance, minute amounts of packaging substances may find their way into foods during storage. Food packaging manufacturers must prove to the FDA that all materials coming in contact with food are safe before they are permitted for use in such a manner.

FDA defines a color additive as any dye, pigment, or substance which—when added or applied to a food, drug, or cosmetic, or to the human body—is capable (alone or through reactions with other substances) of imparting color. FDA is responsible for regulating all color additives to ensure that foods containing color additives are safe to eat, contain only approved ingredients, and are accurately labeled.

Color additives are used in foods for many reasons: 1) to offset color loss due to exposure to light, air, temperature extremes, moisture, and storage conditions; 2) to correct natural variations in color; 3) to enhance colors that occur naturally; and 4) to provide color to colorless and “fun” foods. Without color additives, colas wouldn’t be brown, margarine wouldn’t be yellow, and mint ice cream wouldn’t be green. Color additives are now recognized as an important part of practically all processed foods we eat.

Today, food and color additives are more strictly studied, regulated, and monitored than at any other time in history. FDA has the primary legal responsibility for determining their safe use. To market a new food or color additive (or before using an additive already approved for one use in another manner not yet approved), a manufacturer or other sponsor must first petition FDA for its approval. These petitions must provide evidence that the substance is safe for the ways in which it will be used.

Before any substance can be added to food, its safety must be assessed in a stringent approval process. The Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) shares responsibility with FDA for the safety of food additives used in meat, poultry, and egg products. All additives are initially evaluated for safety by FDA.

When an additive is proposed for use in a meat, poultry, or egg product, its safety, technical function, and conditions of use must also be evaluated by the Risk, Innovations and Management Staff of FSIS, as provided in the Federal Meat Inspection Act, the Poultry Products Inspection Act, the Egg Products Inspection Act, and related regulations.

Although FDA has overriding authority regarding additive safety, FSIS may apply even stricter standards that take into account the unique characteristics of meat, poultry, and egg products. Several years ago, for instance, permission was sought to use sorbic acid in meat salads. Although sorbic acid was an approved food additive, permission for use in meat salad was denied because such usage could mask spoilage caused by organisms that cause foodborne illness.

Additives are never given permanent approval. FDA and FSIS continually review the safety of approved additives, based on the best scientific knowledge, to determine if approvals should be modified or withdrawn.

The statutes and regulations to enforce the statutes require certain information on labels of meat and poultry products so consumers will have complete information about a product. In all cases, ingredients must be listed on the product label in the ingredients statement in order by weight, from the greatest amount to the least.

Substances such as spices and spice extractives may be declared as “natural flavors,” “flavors,” or “natural flavoring” on meat and poultry labels without naming each one. This is because they are used primarily for their flavor contribution and not their nutritional contribution.

Substances such as dried meat, poultry stock, meat extracts, or hydrolyzed protein must be listed on the label by their common or usual name because their primary purpose is not flavor. They may be used as flavor enhancers, binders, or emulsifiers. They must be labeled using the species of origin of the additive, for example, dried beef, chicken stock, pork extract, or hydrolyzed wheat protein.

Color additives must be declared by their common or usual names on labels (for example, FD&C Yellow 5 or annatto extract), not collectively as colorings. These labeling requirements help consumers make choices about the foods they eat. [11]

Artificial Sweeteners

Artificial sweeteners, also called sugar substitutes, are substances that are used instead of sucrose (table sugar) to sweeten foods and beverages. Because artificial sweeteners are many times sweeter than table sugar, much smaller amounts (200 to 20,000 times less) are needed to create the same level of sweetness.

Artificial sweeteners are regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Approved artificial sweeteners include:

- Aspartame, distributed under several trade names (e.g., NutraSweet®and Equal®),

- Sucralose, marketed under the trade name Splenda®

- Acesulfame potassium (also known as ACK, Sweet One®, and Sunett®)

- Neotame, which is similar to aspartame

- Advantame, which is also similar to aspartame

Questions about artificial sweeteners and cancer arose when early studies showed that cyclamate in combination with saccharin caused bladder cancer in laboratory animals. However, results from subsequent carcinogenicity studies (studies that examine whether a substance can cause cancer) of these sweeteners have not provided clear evidence of an association with cancer in humans. Similarly, studies of other FDA-approved sweeteners have not demonstrated clear evidence of an association with cancer in humans.[13] Please note that even if artificial sweeteners have not been shown to cause cancer, it is NOT recommended for use, especially with children. The research on this has been relatively limited and is not conclusive.

The Challenge of Choosing Foods

There are other factors besides environment and lifestyle that influence the foods you choose to eat. Different foods affect energy level, mood, how much is eaten, how long before you eat again, and if cravings are satisfied. We have talked about some of the physical effects of food on your body, but there are other effects too.

Food regulates your appetite and how you feel. Multiple studies have demonstrated that some high fiber foods and high-protein foods decrease appetite by slowing the digestive process and prolonging the feeling of being full or satiety. The effects of individual foods and nutrients on mood are not backed by consistent scientific evidence, but in general, most studies support that healthier diets are associated with a decrease in depression and improved well-being. To date, science has not been able to track the exact path in the brain that occurs in response to eating a particular food, but it is quite clear that foods, in general, stimulate emotional responses in people.

Food also has psychological, cultural, and religious significance, so your personal choices of food affect your mind, as well as your body. The social implications of food have a great deal to do with what people eat, as well as how and when. Special events in individual lives—from birthdays to funerals—are commemorated with equally special foods. Being aware of these forces can help people make healthier food choices—and still honor the traditions and ties they hold dear.

Typically, eating kosher food means a person is Jewish; eating fish on Fridays during Lent means a person is Catholic; fasting during the ninth month of the Islamic calendar means a person is Muslim. On New Year’s Day, Japanese take part in an annual tradition of Mochitsuki also known as Mochi pounding in hopes of gaining good fortune over the coming year. Several hundred miles away in Hawai‘i, people eat poi made from pounded taro root with great significance in the Hawaiian culture, as it represents Hāloa, the ancestor of chiefs and kanaka maoli (Native Hawaiians). National food traditions are carried to other countries when people immigrate.

Factors that Drive Food Choices

Along with these influences, a number of other factors affect the dietary choices individuals make, including:

- Taste, texture, and appearance. Individuals have a wide range of tastes which influence their food choices, leading some to dislike milk and others to hate raw vegetables. Some foods that are very healthy, such as tofu, may be unappealing at first to many people. However, creative cooks can adapt healthy foods to meet most people’s taste.

- Economics. Access to fresh fruits and vegetables may be scant, particularly for those who live in economically disadvantaged or remote areas, where cheaper food options are limited to convenience stores and fast food.

- Early food experiences. People who were not exposed to different foods as children, or who were forced to swallow every last bite of overcooked vegetables, may make limited food choices as adults.

- Habits. It’s common to establish eating routines, which can work both for and against optimal health. Habitually grabbing a fast food sandwich for breakfast can seem convenient, but might not offer substantial nutrition. Yet getting in the habit of drinking an ample amount of water each day can yield multiple benefits.

- Culture. The culture in which one grows up affects how one sees food in daily life and on special occasions.

- Geography. Where a person lives influences food choices. For instance, people who live in Midwestern US states have less access to seafood than those living along the coasts.

- Advertising. The media greatly influences food choice by persuading consumers to eat certain foods.

- Social factors. Any school lunchroom observer can testify to the impact of peer pressure on eating habits, and this influence lasts through adulthood. People make food choices based on how they see others and want others to see them. For example, individuals who are surrounded by others who consume fast food are more likely to do the same.

- Health concerns. Some people have significant food allergies, to peanuts for example, and need to avoid those foods. Others may have developed health issues which require them to follow a low salt diet. In addition, people who have never worried about their weight have a very different approach to eating than those who have long struggled with excess weight.

- Emotions. There is a wide range in how emotional issues affect eating habits. When faced with a great deal of stress, some people tend to overeat, while others find it hard to eat at all.

- Green food/Sustainability choices. Based on a growing understanding of diet as a public and personal issue, more and more people are starting to make food choices based on their environmental impact. Realizing that their food choices help shape the world, many individuals are opting for a vegetarian diet, or, if they do eat animal products, striving to find the most “cruelty-free” options possible. Purchasing local and organic food products and items grown through sustainable products also help shrink the size of one’s dietary footprint.[14]

Pause to Reflect

|

Think of your last meal or snack. What are some of the factors listed above that led you to choose to eat what you did? |

Vegetarian Diet

People choose a vegetarian diet for various reasons, including religious doctrines, health concerns, ecological and animal welfare concerns, or simply because they dislike the taste of meat. There are different types of vegetarians, but a common theme is that vegetarians do not eat meat. Four common forms of vegetarianism are:

- Lacto-ovo vegetarian. This is the most common form. This type of vegetarian diet includes the animal foods eggs and dairy products.

- Lacto-vegetarian. This type of vegetarian diet includes dairy products but not eggs.

- Ovo-vegetarian. This type of vegetarian diet includes eggs but not dairy products.

- Vegan. This type of vegetarian diet does not include dairy, eggs, or any type of animal product or animal by-product. [15]

Preparing vegetarian meals will be addressed further in Chapter 15.

Achieving a Healthy Diet

Achieving a healthy diet is a matter of balancing the quality and quantity of food that is eaten. There are five key factors that make up a healthful diet:

- A diet must be adequate, by providing sufficient amounts of each essential nutrient, as well as fiber and adequate calories.

- A balanced diet results when you do not consume one nutrient at the expense of another, but rather get appropriate amounts of all nutrients.

- Calorie control is necessary so that the amount of energy you get from the nutrients you consume equals the amount of energy you expend during your day’s activities.

- Moderation means not eating to the extremes, neither too much nor too little.

- Variety refers to consuming different foods from within each of the food groups on a regular basis.

A healthy diet is one that favors whole foods. As an alternative to modern processed foods, a healthy diet focuses on “real” fresh whole foods that have been sustaining people for generations. Whole foods supply the needed vitamins, minerals, protein, carbohydrates, fats, and fiber that are essential to good health. Commercially prepared and fast foods are often lacking nutrients and often contain inordinate amounts of sugar, salt, saturated and trans fats, all of which are associated with the development of diseases such as atherosclerosis, heart disease, stroke, cancer, obesity, diabetes, and other illnesses. A balanced diet is a mix of food from the different food groups (vegetables, legumes, fruits, grains, protein foods, and dairy).

Adequacy

An adequate diet is one that favors nutrient-dense foods. Nutrient-dense foods are defined as foods that contain many essential nutrients per calorie. Nutrient-dense foods are the opposite of “empty-calorie” foods, such as sugary carbonated beverages, which are also called “nutrient-poor.” Nutrient-dense foods include fruits and vegetables, lean meats, poultry, fish, low-fat dairy products, and whole grains. Choosing more nutrient-dense foods will facilitate weight loss, while simultaneously providing all necessary nutrients.

Balance

Balance the foods in your diet. Achieving balance in your diet entails not consuming one nutrient at the expense of another. For example, calcium is essential for healthy teeth and bones, but too much calcium will interfere with iron absorption. Most foods that are good sources of iron are poor sources of calcium, so in order to get the necessary amounts of calcium and iron from your diet, a proper balance between food choices is critical. Another example is that while sodium is an essential nutrient, excessive intake may contribute to congestive heart failure and chronic kidney disease in some people. Remember, everything must be consumed in the proper amounts.

Moderation

Eat in moderation. Moderation is crucial for optimal health and survival. Eating nutrient-poor foods each night for dinner will lead to health complications. But as part of an otherwise healthful diet and consumed only on a weekly basis, this should not significantly impact overall health. It’s important to remember that eating is, in part, about enjoyment and indulging with a spirit of moderation. This fits within a healthy diet.

Monitor food portions. For optimum weight maintenance, it is important to ensure that energy consumed from foods meets the energy expenditures required for body functions and activity. If not, the excess energy contributes to gradual, steady accumulation of stored body fat and weight gain. In order to lose body fat, you need to ensure that more calories are burned than consumed. Likewise, in order to gain weight, calories must be eaten in excess of what is expended daily.

Variety

Variety involves eating different foods from all the food groups. Eating a varied diet helps to ensure that you consume and absorb adequate amounts of all essential nutrients required for health. One of the major drawbacks of a monotonous diet is the risk of consuming too much of some nutrients and not enough of others. Trying new foods can also be a source of pleasure—you never know what foods you might like until you try them.

Developing a healthful diet can be rewarding, but be mindful that all of the principles presented must be followed to derive maximal health benefits. For instance, introducing variety in your diet can still result in the consumption of too many high-calorie, nutrient poor foods and inadequate nutrient intake if you do not also employ moderation and calorie control. Using all of these principles together will promote lasting health benefits.[17]

Pause to Reflect

|

Think back to your childhood, how do you think your diet did with regards to adequacy, balance, moderation, and variety? What about your diet now? |

Chapter 12 Workbook (Part One)

STOP HERE for Nutrition Lesson One

Nutrition in Early Care and Education Programs

There are many different programs that can support early care and education programs in providing nutritious meals and snacks for children. Let’s explore a few of these.

Child and Adult Care Food Program

The Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) is a federal program that provides reimbursements for nutritious meals and snacks to eligible children and adults who are enrolled for care at participating child care centers, day care homes, and adult day care centers. Eligible public or private nonprofit child care centers, outside-school-hours care centers, Head Start programs, and other institutions which are licensed or approved to provide day care services may participate in CACFP, independently or as sponsored centers.[18] Over 2 billion meals are served in the CACFP.[19]

Even if a program chooses not to participate in (or is ineligible for) the CACFP, they are required by licensing to its meal plan requirements. [20] (See Tables 12.4 and 12.5) The CACFP nutrition standards for meals and snacks served in the CACFP are based on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, science-based recommendations made by the National Academy of Medicine, cost and practical considerations, and stakeholder’s input. Under these standards, meals and snacks served include a greater variety of vegetables and fruit, more whole grains, and less added sugar and saturated fat.[21] (See Table 12.6)

Table 12.4 – Infant Meal Patterns [22]

| Meal or snack | 0-5 Months | 6-11 Months |

| Breakfast | 4-6 fl oz breastmilk or formula | 6-8 fl oz breastmilk or formula

0-4 tbsp infant cereal, meat, fish, poultry, whole eggs, cooked dry beans or peas; or 0-2 oz cheese; or 0-4 oz (volume) cottage cheese; or 0-4 oz yogurt; or a combination* 0-2 tbsp vegetable, fruit or both* |

| Lunch or Supper | 4-6 fl oz breastmilk or formula | 6-8 fl oz breastmilk or formula

0-4 tbsp infant cereal, meat, fish, poultry, whole eggs, cooked dry beans or peas; or 0-2 oz cheese; or 0-4 oz (volume) cottage cheese; or 0-4 oz yogurt; or a combination* 0-2 tbsp vegetable, fruit or both* |

| Snack | 4-6 fl oz breastmilk or formula | 2-4 fl oz breastmilk or formula

0-½ bread slice; or 0-2 crackers; or 0-4 tbsp infant cereal or readyto-eat cereal* 0-2 tbsp vegetable, fruit or both* |

Solid foods are required when infant is ready. All serving sizes are minimum quantities of the food components that are required to be served

Table 12.5 – Meal Pattern for Children [23]

Breakfast

| Meal or snack | Food Item | 1-2 Years | 3-5 Years | 6-18 Years |

| Breakfast | Milk | ½ cup whole | ¾ cup low-fat or fat-free | 1 cup low-fat or fat-free |

| Vegetables, fruit, or both | 1/4 cup | ½ cup | 1/2 cup | |

| Grains | ½ ounce equivalent | 1/2 ounce equivalent | 1 ounce equivalent |

Lunch or Supper

| Meal or snack | Food Item | 1-2 Years | 3-5 Years | 6-18 Years |

| Lunch or Supper | Milk | ½ cup whole | ¾ cup low-fat or fat-free | 1 cup low-fat or fat-free |

| Meat and meat alternative | 1 ounce | 1½ ounces | 2 ounces | |

| Vegetables | 1/8 cup | 1/4 cup | ½ cup | |

| Fruits | 1/8 cup | ¼ cup | ¼ cup | |

| Grains | ½ ounce equivalent | ½ ounce equivalent | 1 ounce equivalent |

Snack (choose 2 of the options)

| Meal or snack | Food Item | 1-2 Years | 3-5 Years | 6-18 Years |

| Snack

(choose 2 of the options) |

Milk | ½ cup whole | ½ cup low-fat or fat-free | 1 cup low-fat or fat-free |

| Meat and meat alternative | ½ ounce | ½ ounce | 1 ounce | |

| Vegetables | ½ cup | ½ cup | ¾ cup | |

| Fruits | ½ cup | ½ cup | ¾ cup | |

| Grains | ½ ounce equivalent | ½ ounce equivalent | 1 ounce equivalent |

| Category | Best Practices |

| Vegetables and Fruit | · Make at least one of the two required components of snack a vegetable or fruit

· Serve a variety of fruit and choose whole fruits · Juice is limited to once a day · Provide at least one serving each of dark green leafy vegetables, red and orange vegetables, beans and peas (legumes), starchy vegetables, and other vegetables each week |

| Grains | · Provide at least two servings of whole grains per day (at least one is required) |

| Meat and Meat Alternatives | · Serve only lean meats, nuts, and legumes.

· Limit serving processed meats to no more than one serving per week. · Serve only natural cheeses and choose low-fat or reduced fat-cheeses. |

| Milk | · Serve only unflavored milk

· Nondairy milk substitutes that are nutritionally equivalent to milk may be served in place of milk to children with medical or special dietary needs |

| Sugar | · Yogurt must contain no more than 23 grams per 6 ounces

· Breakfast cereals must contain no more than 6 grams of sugar per dry ounce · Avoid serving non-creditable foods that are sources of added sugars, such as sweet toppings (honey, jam, syrup), mix-in ingredients sold with yogurt, and sugar sweetened beverages |

| Miscellaneous | · Frying is not allowed as a way of preparing foods on-site

· Limit serving purchased pre-fired foods to no more than one serving per week · Incorporate seasonal and local produced foods into meals |

Healthy Beverages in Child Care Act

“And all licensed child care providers…must follow the Healthy Beverages in Child Care Act. The four key messages in the Healthy Beverages in Child Care Act are:

- Only unflavored, unsweetened, non-fat (fat free, skim, 0%) or low fat (1%) milk can be served to children 2 years of age or older.

- No beverages with added sweeteners, natural or artificial, can be served, including sports drinks, sweet teas, juice drinks with added sugars, flavored milk, soda, and diet drinks.

- A maximum of one serving of 100% juice is allowed per day.

- Clean and safe drinking water must be readily available at all times; indoors and outdoors and with meals and snacks.” [26]

Dietary Guidelines for Americans

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans provides evidence-based nutrition information and advice for people ages two and older to help Americans make healthy choices about food and beverages in their daily lives. The Guidelines also serve as the basis for federal food and nutrition education programs, like the MyPlate campaign.

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans, produced by HHS and the U.S. Department of Agriculture every five years, analyze the latest research to help Americans make smart choices about food and physical activity so they can live healthier lives.

The 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans focuses on making small shifts in your daily eating habits to improve your health over the long run. They also emphasize the importance of “eating patterns,” which refer to the combination of ALL foods and beverages a person consumes regularly over time, rather than focusing on individual nutrients or foods in isolation. Healthy eating patterns, along with regular physical activity, have been shown in a large body of current science to help people reach and maintain good health while reducing risks of chronic disease throughout their lives. Additionally, healthy eating patterns can be adapted to an individual’s budget, taste preferences, traditions, and culture.

The core recommendations for these healthy eating patterns are unchanged from previous editions of the Guidelines, and continue to encourage Americans to consume more healthy foods like vegetables, fruits, whole grains, fat-free and low-fat dairy products, lean meats, seafood, other protein foods, and oils. They also recommend limiting sodium, saturated and trans fats, and added sugars.

There are five overarching guidelines in this eighth edition:

- Follow a healthy eating pattern across the lifespan. Eating patterns are the combination of foods and drinks that a person eats over time.

- A variety of vegetables: dark green, red and orange, legumes (beans and peas), starchy and other vegetables.

- o Fruits, especially whole fruit.

- o Grains, at least half of which are whole grain.

- o Fat-free or low-fat dairy, including milk, yogurt, cheese, and/or fortified soy beverages.

- o A variety of protein foods, including seafood, lean meats and poultry, eggs, legumes (beans and peas), soy products, and nuts and seeds.

- o Oils, including those from plants: canola, corn, olive, peanut, safflower, soybean, and sunflower. Oils also are naturally present in nuts, seeds, seafood, olives, and avocados.

- Focus on variety, nutrient-dense foods, and amount.

- Limit calories from added sugars and saturated fats, and reduce sodium intake.

- Children younger than 14 should consume less than 2.300 mg of sodium per day.

- Less than 10% of daily calories should come from saturated fats.

- Less than 10% of daily calories should come from added sugars

- Shift to healthier food and beverage choices.

- Support healthy eating patterns for all.[27]

Physical Guidelines for Americans

The second edition of the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans issued by the Department of Health and Human Services provides science-based guidance to help people ages 3 years and older improve their health through participation in regular physical activity. Key guidelines include:

Preschool-Aged Children

Preschool-aged children (ages 3 through 5 years) should be physically active throughout the day to enhance growth and development. Adult caregivers of preschool-aged children should encourage active play that includes a variety of activity types.

Children and Adolescents

It is important to provide young people opportunities and encouragement to participate in physical activities that are appropriate for their age, that are enjoyable, and that offer variety. Children and adolescents ages 6 through 17 years should do 60 minutes (1 hour) or more of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity daily that includes activity that is aerobic, muscle-strengthening, and bone-strengthening.[28]

Physical activity will be addressed further in Chapter 13.

MyPlate

MyPlate is the United States Department of Agriculture’s food guidance program to help Americans eat healthy and is based on the Dietary Guidelines for America. It replaces MyPyramid (which had replaced the classic Food Guide Pyramid).

The visual for MyPlate is a familiar mealtime symbol, the plate. It gives easy visual reference to remind people to create balanced meals. The main messages of MyPlate include:

- Make half the plate fruits and vegetables

- o Focus on whole fruits.

- o Vary your veggies.

- Make half the grains whole grains.

- Move to low-fat or fat-free milk or yogurt.

- Vary the sources of protein.[29]

1992: Food Guide Pyramid |

2005: MyPyramid Food Guidance System |

2011: MyPlate |

12.5 – The most recent Food Guides from the USDA.[30]

Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI)

Issued by the Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences, the DRI is the general term for a set of reference values used to plan and assess nutrient intakes of healthy people. These values, which vary by age and sex, include:

- Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA): average daily level of intake sufficient to meet the nutrient requirements of nearly all (97%-98%) healthy people.

- Adequate Intake (AI): established when evidence is insufficient to develop an RDA and is set at a level assumed to ensure nutritional adequacy.

- Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL): maximum daily intake unlikely to cause adverse health effects.[31]

That information is used to create nutrition fact labels.

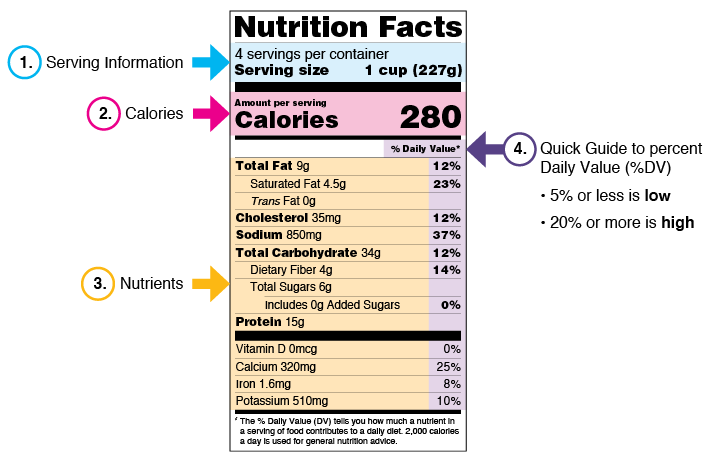

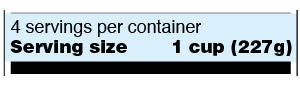

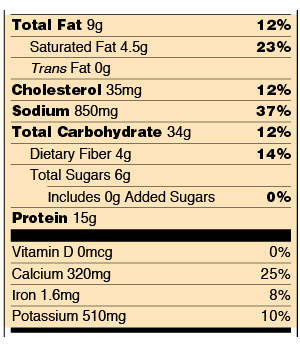

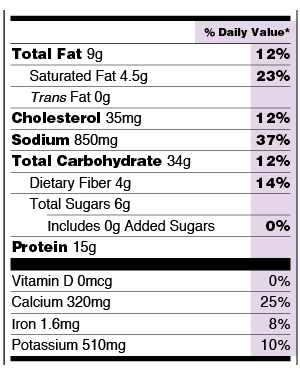

Nutrition Facts Labels

The information in the main or top section (see #1-4) of the sample nutrition label (below) can vary with each food and beverage product; it contains product-specific information (serving size, calories, and nutrient information). The bottom section contains a footnote that explains the % Daily Value and gives the number of calories used for general nutrition advice.

In the following Nutrition Facts label certain sections have been colored to help focus on those areas that will be explained in detail. Note that these colored sections are not on the actual food labels of products you purchase.

-

Serving Information

When looking at the Nutrition Facts label, first take a look at the number of servings in the package (servings per container) and the serving size. Serving sizes are standardized to make it easier to compare similar foods; they are provided in familiar units, such as cups or pieces, followed by the metric amount, e.g., the number of grams (g). The serving size reflects the amount that people typically eat or drink. It is not a recommendation of how much you should eat or drink.

It’s important to realize that all the nutrient amounts shown on the label, including the number of calories, refer to the size of the serving. Pay attention to the serving size, especially how many servings there are in the food package. For example, you might ask yourself if you are consuming ½ serving, 1 serving, or more.

-

Calories

Calories provide a measure of how much energy you get from a serving of this food.

In the example, there are 280 calories in one serving of lasagna. What if you ate the entire package? Then, you would consume 4 servings, or 1,120 calories.

- Nutrients

Look at section 3 in the sample label (shown in Table 12.9). It shows you some key nutrients that impact your health. Two key facts about the nutrients:

- Nutrients to get less of: Saturated Fat, Sodium, and Added Sugars.

- Nutrients to get more of: Dietary Fiber, Vitamin D, Calcium, Iron, and Potassium.

-

The Percent Daily Value (%DV)

The % Daily Value (%DV) is the percentage of the Daily Value for each nutrient in a serving of the food. The Daily Values are reference amounts (expressed in grams, milligrams, or micrograms) of nutrients to consume or not to exceed each day.

The %DV shows how much a nutrient in a serving of a food contributes to a total daily diet for adults. The %DV helps you determine if a serving of food is high or low in a nutrient.[37]

Pause to Reflect

|

Find a food that is marketed to young children (that has a food label). Looking at the label, how do you think it rates a healthy choice? Why? |

Child Nutrition Programs for Schools

The federal government provides federal assistance to schools to provide nutritious meals to children. With the exception of the Special Milk Program, early care and education programs will not qualify for these programs. But they are included in this chapter as they are important sources of nutrition for many children in the U.S., for reference for those that may work within the school system, and they may provide resources that early care and education programs may find useful when planning healthy meals and snacks and purchasing foods.

National School Lunch Program

The National School Lunch Program (NSLP) is a federally assisted meal program operating in public and nonprofit private schools and residential child care institutions. It provides nutritionally balanced, low-cost or no-cost lunches to children each school day. The program was established under the Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act, signed into law by President Harry Truman in 1946. 30.4 million children participated in the program in 2016.[38]

School Breakfast Program

The School Breakfast Program (SBP) is a federally assisted meal program operating in public and non-profit private schools and residential child care institutions. The SBP started in 1966 as a pilot project, and was made a permanent entitlement program by Congress in 1975. Participation in the SBP has slowly but steadily grown over the years and in 2016, 14.57 million children participated in the program.[40]

Special Milk Program

The Special Milk Program provides milk to children in schools, child care program and eligible camps that do not participate in other federal child nutrition meal service programs. The program reimburses schools and institutions for the milk they serve. In 2011, 3,848 schools and residential child care institutions participated, along with 782 summer camps and 527 non‐residential child care institutions. Schools in the National School Lunch or School Breakfast Programs may also participate in the Special Milk Program to provide milk to children in half‐day pre‐kindergarten and kindergarten programs where children do not have access to the school meal programs.[41]

Summer Food Service Program

The Summer Food Service Program (SFSP) provides free meals and snacks when school is not in session. The seasonal nature of SFSP, and the diversity of sponsors and site operators, make it unique. State agencies, sponsors, and community organizations need flexibility to operate the SFSP in a manner that is responsive to local conditions and allows operators to focus on ensuring children in need can access food when school is not in session. In the summer of 2018 over 145 million meals were served to over 2.6 million children.[42]

Assessing Quality of Meal and Snack Times

Just like with safety and health (and many other things), early care and education programs should assess how well they are meeting children’s nutritional needs with the meals and snacks they are providing for children. An assessment, such as one in Appendix N can be used to help programs do this. You will notice that providing a positive eating environment takes more than just giving children healthy food. Chapter 14 will look more at this by age.

Summary

Providing nutritious meals and snacks to children in early care and education programs requires a basic understanding of nutrition. Program staff should also have an understanding of what a complete and healthy diet includes and how to address factors that influence food choices, to ensure that they provide healthy food and beverages that children will enjoy eating. Being aware of the programs available to support doing so is also valuable. Children that have high-quality meal and snack times will have the fuel their bodies need to sustain optimal growth and development.

Chapter 12 Review

Resources for Further Exploration

· Nutrition.gov: https://www.nutrition.gov/

· Nutrition: https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/

· Definitions of Health Terms: Nutrition: https://medlineplus.gov/definitions/nutritiondefinitions.html

· Nutrition Education Resources & Materials: https://www.fda.gov/food/food-labeling-nutrition/nutrition-education-resources-materials

· Consumer Information on Ingredients & Packaging: https://www.fda.gov/food/food-ingredients-packaging/consumer-information-ingredients-packaging

· Overview of Food Ingredients, Additives & Colors: https://www.fda.gov/food/food-ingredients-packaging/overview-food-ingredients-additives-colors

· Preventing Childhood Obesity in Early Care and Education Programs: https://nrckids.org/CFOC/Childhood_Obesity

· ChooseMyPlate: https://www.myplate.gov/

· Child and Adult Care Food Program: https://www.fns.usda.gov/cacfp/child-and-adult-care-food-program

· CACFP Regulations: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2016-04-25/pdf/2016-09412.pdf

· Nutrition Standards for CACFP Meals and Snacks: https://www.fns.usda.gov/cacfp/meals-and-snacks

· Food and Nutrition Service Programs: https://www.fns.usda.gov/programs

· Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015-2020: https://health.gov/our-work/food-nutrition/2015-2020-dietary-guidelines

· Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans: https://www.hhs.gov/fitness/be-active/physical-activity-guidelines-for-americans/index.html

· Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care: https://gonapsacc.org/self-assessment-materials

Chapter 12 Workbook (part 2)

References:

[1] Image by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0

[2] Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0

[3] Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0

[4] Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0

[5] Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0

[6] Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0

[7] Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0

[8] Salt Shaker on White Background by Dubravko Sorić is licensed under CC BY 2.0

[9] Image by Suzy Hazelwood on Pexels

[10] Food Coloring Bottles by Larry Jacobson is licensed under CC BY 2.0

[11] Additives in Meat and Poultry Products by the USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service is in the public domain

[12] No-Calorie Sweetener Packets by Evan Amos is in the public domain

[13] Artificial Sweeteners and Cancer by the National Cancer Institute is in the public domain

[14] Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0

[15] Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0

[16] Image by the USDA Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion is in the public domain

[17] Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0

[18] Child and Adult Care Food Program by the USDA Food and Nutrition Service is in the public domain

[19] Child and Adult Care Food Program (PDF) by the USDA Food and Nutrition Service is in the public domain

[20] California Childcare Health Program. (2018). Preventive Health and Safety in the Child Care Setting: A Curriculum for the Training of Child Care Providers (3rd ed.). University of California, San Francisco. Retrieved from https://cchp.ucsf.edu/sites/g/files/tkssra181/f/PHT-Handbook-Student-2018-FINAL.pdf

[21] Nutrition Standards for CACFP Meals and Snacks by the USDA Food and Nutrition Service is in the public domain

[22] Updated Child and Adult Care Food Program Meal Patterns: Infant Meals by the USDA Food and Nutrition Service is in the public domain

[23] Updated Child and Adult Care Food Program Meal Patterns: Child and Adult Meals by the USDA Food and Nutrition Service is in the public domain

[24] Child and Adult Care Food Program: Best Practices by the USDA Food and Nutrition Service is in the public domain

[25] Updated Child and Adult Care Food Program Meal Patterns: Child and Adult Meals by the USDA Food and Nutrition Service is in the public domain

[26] California Childcare Health Program. (2018). Preventive Health and Safety in the Child Care Setting: A Curriculum for the Training of Child Care Providers (3rd ed.). University of California, San Francisco. Retrieved from https://cchp.ucsf.edu/sites/g/files/tkssra181/f/PHT-Handbook-Student-2018-FINAL.pdf

[27] Dietary Guidelines for Americans by the President’s Council on Sports, Fitness & Nutrition is in the public domain

[28] Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans by the President’s Council on Sports, Fitness & Nutrition is in the public domain

[29] What is MyPlate? by the USDA Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion is in the public domain

[30] Images by the U.S. Department of Agriculture are in the public domain

[31] Nutrient Recommendations: Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI) by the National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements is in the public domain

[32] Image by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration is in the public domain

[33] Image by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration is in the public domain

[34] Image by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration is in the public domain

[35] Image by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration is in the public domain

[36] Image by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration is in the public domain

[37] How to Understand and Use the Nutrition Facts Label by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration is in the public domain

[38] National School Lunch Program (NSLP) Fact Sheet by the USDA Food and Nutrition Service is in the public domain

[40] SBP Fact Sheet by the USDA Food and Nutrition Service is in the public domain

[41] Special Milk Program (SMP) Fact Sheet by the USDA Food and Nutrition Service is in the public domain

[42] Regulatory Reform at a Glance—Proposed Rule: Summer Meals Program Streamlining & Integrity by the U.S. Department of Agriculture is in the public domain

[43] FCC Program Offers Jobs, Safe Child Care by Fort Rucker is licensed under CC BY 2.0