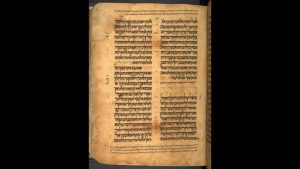

The Writings: Ketuvim

KETUVIM (Writings)

The Ketuvim is the third portion of the Tanakh, generally considered the last portion to have been accepted as Biblical canon. There is mixed scholarly consensus as to when the Hebrew Bible canon came to be fixed as it is known now: some argue that it was fixed by the Hasmonean dynasty in or about the 1st century BCE, while others argue it was not fixed in format until the second century CE or even later.

The Torah may have been fixed in canonical status as early as the 5th century BCE, and the Former and Latter Prophets were likely canonized by the 2nd century BCE, but Michael Coogan[1] says that the Ketuvim was not a fixed canon until the 2nd century CE.

A list of the materials generally considered to be the Writings, or in Christian terminology, the Wisdom Literature, would be:

- Psalms: 150 poetic writings of various types (praise, petition, lament, thanksgiving)

- Proverbs: A collection of sayings and aphorisms, including tributes to wisdom itself

- Job: The tale of a righteous man afflicted with suffering is the prose framework for a lengthy poetic dialogue on the question of divine justice, human suffering, and the value of righteousness.

- The Five Scrolls

1. Song of Songs – An erotic multi-voiced love poem

2. Ruth – Story of a foreign women’s faithfulness to her Israelite family by marriage set in the period of the judges

3. Lamentations – Dirge on the destruction of Jerusalem

4. Ecclesiastes – Musings on the vanity of life

5. Esther – Story of Mordechai and Esther who save the Jews of Persia from a planned

slaughter. - Daniel- Written in the 2nd century BCE., this book contains the adventures of the Israelite Daniel and his friends residing in the royal court of 6th century BCE Babylon. The latter part of the book contains apocalyptic visions.

- Ezra – Relates the return of the Babylonian exiles to Judea at the end of the 6th century BCE and the reforms of Ezra, a Babylonian priest and scribe, in the 5th century BCE.

- Nehemiah – Relates the activities of Nehemiah, governor of Judah under Persian rule, in the mid-5th century BCE.

- 1 Chronicles – A recapitulation of the history of Israel down to the reign of David, with different emphases and themes than found in the books of Kings

- 2 Chronicles – A continuation of I Chronicles relating the reigns of the kings of Judah down to the Babylonian exile.

In the Hebrew Bible, Chronicles would be one book and Ezra-Nehemiah would be a single book. These have been separated out in the Christian Old Testament.

Israelite Wisdom literature is much like Wisdom tradition found all across the Ancient Near East. This style of Wisdom literature attempts to understand the ways of the world and how best to live in it successfully. The writing in this set of books tends to be quite universal in application, focused on the wisdom of living for each individual. So Israelite Wisdom literature doesn’t speak to the particular historical condition of Israel at all. Instead, it speaks to the general human condition. It also makes no claim to having been divinely revealed, but instead is simply advice and counsel that can be weighed or confirmed or disputed by human experience. The Hebrew word for wisdom, hokhmah, often comes to mean skill, which refers to the skill of living well or behaving properly.

The wise man (or person, but this was material often aimed at men) was not particularly nationalistic in description throughout these materials, and often had no visible connection to the history of Israel nor the cultic worship of Yahweh. The teachers said, and the students understood, that people were to gain their wisdom from receiving good teaching, having varied life experiences, and finally from human observation of how things worked in the world, not from divine revelation or prophecy. The writers and teachers clearly believed in God, and in God’s ordering of the universe. The materials considered the Wisdom Literature can certainly be held alongside the Prophets and the Law as part of Israelite ethical teachings, whether specific to the people or Israel or more universal.

There are various types of Wisdom material. Scholars have classified the Wisdom material into three general categories–and this is perhaps somewhat over-simplified. In general, however, the three types of Wisdom literature identified are:

- Clan or family wisdom. These materials tend to be common sense aphorisms and observations, the kinds of things that are common to all cultures. They’re scattered around the Hebrew Bible, but most of them are contained in the Book of Proverbs.

- Court wisdom, a lot of which comes originally from Egypt and Mesopotamia. It tends to be bureaucratic advice, administrative advice, career advice, instruction on manners or tact, how to be diplomatic, how to live well and prosper — it is practical wisdom.

- Existential reflection or probing — a reflective probing into the critical problems of human existence, an example of which would be the Book of Job.

Coogan, Michael. A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament: The Hebrew Bible in Its Context. Oxford University Press, 2009

May, Herbert G., et al. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha: Revised Standard Version, Containing the Second Edition of the New Testament and an Expanded Edition of the Apocrypha. Edited by Michael D Coogan, Oxford University Press, 2007.

Gabel, John B. The Bible as Literature: An Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Michael Coogan is Director of Publications for the Harvard Semitic Museum, Professor of Religious Studies at Stonehill College, and Lecturer on Old Testament/Hebrew Bible at Harvard Divinity School. Professor Coogan is the author of A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament: The Hebrew Bible in Its Context (2009), The Old Testament: A Very Short Introduction (2008), and The Old Testament: A Historical and Literary Introduction to the Hebrew Scriptures (2006; 2010). He is the editor of The New Oxford Annotated Bible (2001; 2007; 2010) and Oxford Biblical Studies Online. ↵

The Hasmonean dynasty Hebrew: חַשְׁמוֹנַאִים was a ruling dynasty of Judea and surrounding regions during classical antiquity, from c. 140 BCE to 37 BCE.The Hasmonean rulers took the Greek title basileus ("king" or "emperor"). Forces of the Roman Republic conquered the Hasmonean kingdom in 63 BCE; Herod the Great displaced the last reigning Hasmonean client-rulers in 37 BCE.

ḥokhmah indicates ethical virtue and character as well as practical accomplishment