Beginnings of the Christian Writings

The Christian Bible consists of two sections. The first incorporates the Hebrew scriptures, eventually called the Old Testament by Christians. The earliest Christians adopted a Greek version of this Hebrew text, known as the Septuagint.

The second section of Christian scriptures is a collection of texts concerning the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth, and materials from early followers, all originally written in Greek and together known as the New Testament. There are 4 basic categories of materials found here: gospels, history, letters and an apocalypse. Within these sections, there are types of writing including parables, poetry, prophecy, sermons, proverbs, and much more. This second section of writings is the material used only by Christians. As Christianity spread, and handwritten copies of the Christian scriptures multiplied, the Bible was translated into vernacular/common languages, including Syriac, Coptic, Ethiopian and Armenian.

Some good basics about the Christian Bible: Sacred Texts from the British Library

This section will have some assistance from the works of Dr. Scott McKendrick[1], from Dr. Alec Ryrie[2] and from Dr. Annie Sutherland[3] from an article at the British Library Sacred Texts website. For the full articles, please go to Sacred Texts: The Christian Bible , From Sacred Scriptures to the People’s Bible and The Importance of Translation in the Transmission of Christianity

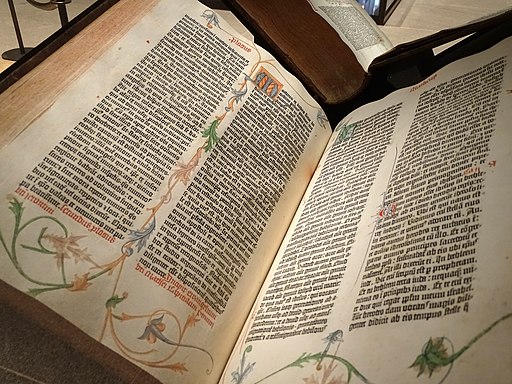

In Western Europe, translations of the Bible into Latin produced by the scholar Jerome (d. 420 CE) became the standard translation that Christians across Europe used for over a thousand years. Known as the Vulgate ( meaning the “common”) version, this text was used in the earliest large-scale work printed in Europe using movable type. (the Gutenberg Bible)

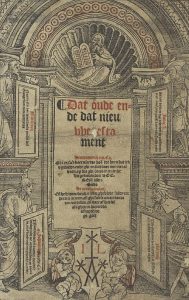

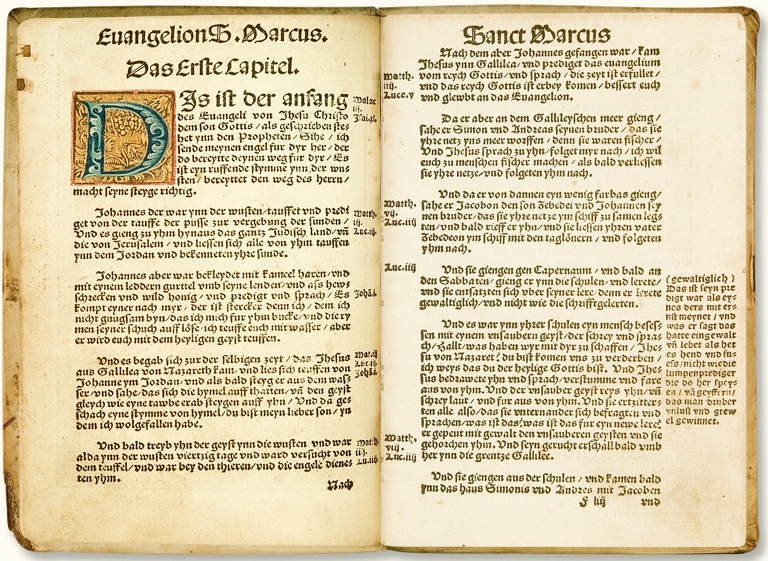

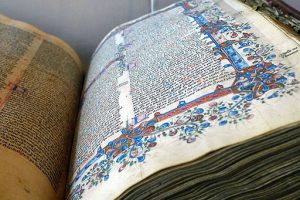

In the Middle Ages most Christian Biblical manuscripts were small selections of books instead of complete Bibles; Gospel-books and Psalters (the book of the psalms) were especially common. Bibles in the vernacular were at first very hard to come by, and there was a great deal of violence and death surrounding making the Bible available to ordinary people. Bibles were published in German, English, and eventually virtually every language that wanted access to the Biblical text. It is interesting to see these translations, as different languages do varying things with the original Hebrew and Greek!

About Christianity: Jewish Roots

Take some time to listen to this OnBeing interview with Dr. Joel Marcus[4] about Jewish Roots of the Christian Story

Americans live in a post-Christian culture, and both aspects of that term are important. It’s post-Christian in the sense that it’s hard to live in the Americas or, really, in most of the world, without having some kind of exposure to Christianity and without seeing its influence on our society, politics, culture, and art. But it’s also post-Christian because people can no longer assume, in a much more global approach to culture, that everybody (at least in North America) is going to be Christian. The reality now is that there are the remnants of Christianity still occupying the culture, but that people don’t necessarily know a lot about the actual history and content of the faith. It helps to understand parts of the global culture if Christianity, its writings, and its history are also understood.

Where are Christians? Where will they be in the future?

Pew Research does extraordinary work in gathering data about many topics, religion being one of them. This link will allow some searching into where people of Christian background have been, and the projections for where they may or may not be in the future, depending on current trends. Global Religious Futures

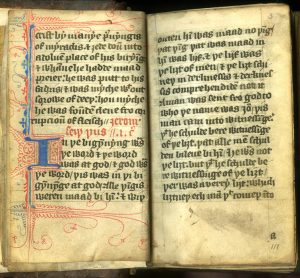

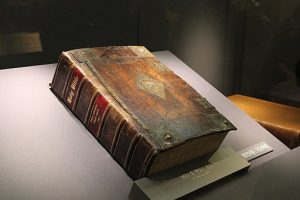

New Testament English late 14th Century. Wycliffe Translation.

What is the New Testament?

While opinions differ over the content (which books are included) of the Old Testament or Hebrew Scriptures, generally Protestants, Roman Catholics and Eastern Orthodox Christians all accept the same New Testament canon. This list of books was formed over a much shorter period than it took to create and agree on the Jewish scriptural canon. The New Testament includes a number of distinct texts–it is not just one long read from beginning to end! The key focus of the New Testament are the Four Gospels–Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. The word ‘gospel’ is possibly derived from the Old English translation of the Latin word evangelium, which is itself based on the Greek εὐαγγέλιον (good news) and is the origin of the term for the authors of these texts, the Evangelists. “Gospel” was a term commonly used very early in Christian history, and “the gospel of Jesus Christ” or “the gospel of God” are terms found within the Bible in various places.

Initially, many accounts of the Gospel (the story about Jesus) were in circulation, and some, like the Gospel of Nicodemus, continued in popularity throughout the Middle Ages. However, the Four Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John were widely accepted as uniquely authoritative from an early date. Their Gospels comprise individual witnesses to the life, teachings, death and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth, and to his status as the Christ (‘Anointed One’), or Messiah, predicted as the Christians believed, in the Hebrew Prophets.

The other twenty-three books of the New Testament include the Acts of the Apostles, in which Luke (the ascribed author) recounts the life of the Church immediately after Jesus’s ascension, Epistles (letters) to early Christian communities or individuals written by the Apostle Paul and other early Christian leaders, and an apocalyptic account, or Revelation, traditionally attributed to a man named John.

The complete list: New Testament

-

Gospel According to Matthew

-

Gospel According to Mark

-

Gospel According to Luke

-

Gospel According to John

-

Acts of the Apostles

-

Letter to the Romans

-

Letters to the Corinthians

-

I Corinthians

-

II Corinthians

-

-

Letter to the Galatians

-

Letter to the Ephesians

-

Letter to the Philippians

-

Letter to the Colossians

-

Letters to the Thessalonians

-

I Thessalonians

-

II Thessalonians

-

-

Letters to Timothy

-

I Timothy

-

II Timothy

-

-

Letter to Titus

-

Letter to Philemon

-

Letter to the Hebrews

-

Letter of James

-

Letters of Peter

-

I Peter

-

II Peter

-

-

Letters of John

-

I John

-

II John

-

III John

-

-

Letter of Jude

-

Revelation to John

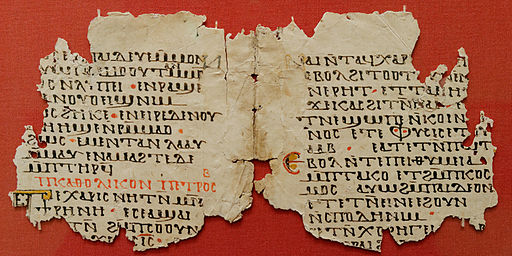

Although the core of the New Testament canon, the Four Gospels and thirteen Epistles of Paul, was established by the middle of the 2nd century CE, the full canon of twenty-seven books was formally confirmed only during the 4th century CE. Until then, some books, such as Hebrews and Revelation, were hotly debated, and other texts, such as the Epistle of Barnabas and Shepherd of Hermas, were only considered authoritative by a smaller number of Christians and did not make the final list. All of the books of the New Testament were originally written in Greek, the main language of the literate community in the region, to further the evangelizing purpose of the New Testament.

Early translations of the Bible

By the 4th and 5th centuries CE the language of the Bible had changed. As the Christian faith spread to other regions and nations beyond Israel and the eastern Mediterranean, the Christian Scripture was also translated into other languages, beginning with those of the earliest converts. Known to Biblical scholars as the Versions and recognized by scholars as important witnesses to the earliest forms of the text of the Bible, these texts included translations into Coptic, Syriac, Armenian, Georgian and Ethiopic.

In the East, through the work of Syriac missionaries, Syriac translations were widely disseminated into Persia, Arabia, India and Central Asia and gave rise to the earliest versions in other languages used in those areas. Some Versions include some additional non-canonical books, such as the Third Epistle to the Corinthians cited by St Gregory the Illuminator (d. 332) which was also included in many later copies of the Armenian New Testament.

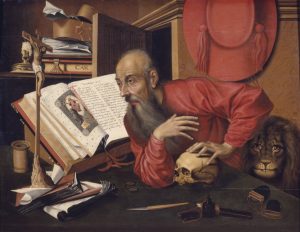

In the West, by the end of the 2nd century CE, Latin was the most widely used language, and Latin versions of the Bible were circulating in both Gaul (a historical region in Western Europe) and North Africa. More significantly, the early Christian scholar Jerome (d. 420 CE) initiated a translation and revision of the complete Bible into Latin, authorized by the Pope.

Working first in Rome and then in Bethlehem, Jerome used Hebrew and Greek texts but also drew on the Old Latin versions of the Bible to make his translation. Jerome spent half his life on his translations.

Jerome’s legacy to the Church, was critical. The Vulgate (or common) Latin version that Jerome created became the single, authoritative version of Christian Scripture in Western Europe for over one thousand years. During this period any translation of the Bible into Western languages were made from the Vulgate. None of those translations, however, was regarded as having the authority of its model. They were regarded as aids to understanding the Scripture, not as Scripture itself. Only the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century CE brought new authoritative Western translations of the entire Bible based on the original Hebrew and Greek texts. These vernacular translations of the Bible in Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries formed the basis of what now is read as the Bible.

In the generation before the Protestant Reformation, two parallel changes – a technological and an intellectual revolution – changed what a ‘sacred text’ could be.

The advent of printing in Europe

The first change was the invention of printing with moveable type by Johannes Gutenberg in the early 1450s. It ought to have been a dubious proposition: a technique requiring hefty capital investment and a string of skilled craftsmen in order to mass-produce an expensive commodity which was entirely useless to most people. In fact, however, printing as a technique spread across Europe so quickly that by 1500 printing presses were soon being set up in peripheral European cities such as London (1475) and Edinburgh (1507). The backbone of the early printing industry was religious texts: books of hours (prayer books), psalters, liturgical texts and, of course, Bibles.

Re-conceptualizing the Bible as one book

Medieval Christians revered the Holy Scriptures, but had little access to them. They generally saw them as plural Scriptures rather than a single Bible. Manuscripts of the whole Bible were a rarity: they were physically huge and very expensive. Individual books of the Bible, or sets of books, were the norm. Print not only made many more copies of the Scriptures available, it helped to redefine them as one book: the Bible, bound between one set of covers. God’s truth was now encapsulated in what (to those unfamiliar with books) looked like a box of treasures which anyone might open. By the early 16th century it began to seem that ‘the Bible’ was a single thing, which could speak God’s truth with one voice and, potentially, be a yardstick against which the Church could be measured.

For Martin Luther the Bible was central to faith. As a professor in the early 1510s, he had used a ‘naked Bible’ which only included the sacred text itself, shorn of the array of marginal comments that usually guided medieval scholars. Luther eventually chose a slogan: sola Scriptura, ‘Scripture alone’. God’s Word was the master of his conscience, he said, and was the only authority he acknowledged. While in hiding in 1521–22 CE , Luther decided to make good on this claim by making a translation of his own into German. The Luther Bible became not only the foundation text of the German Reformation, but also the foundation text of the modern German language.

Illegal English Bibles

Learning a bit about early translators–it was dangerous!

England was the only European country that banned Biblical translation outright. In 1523 CE, a humanist named William Tyndale approached the bishop of London to ask if he would rescind the ban and sponsor an English New Testament. The bishop refused, whereupon Tyndale took his project into exile, and in 1525 CE set about trying to have it printed. The first complete, printed English New Testament was produced in 1526 CE, and it became the most influential text in the history of the English language. Putting the Bible in the common people’s language and into their hands set in motion a momentous and permanent shift of religious power away from the Church and the university elites.

Even so, the ban on English Bibles stood, and Tyndale’s New Testament was illegal. Hence its size: it was very small, designed to be smuggled and concealed.

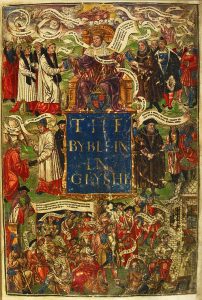

Date 1539

The first official English Bibles

The chance to produce a legal English Bible – the central ambition of the Protestant reformers – was worth almost any compromise. The first full Bible in English was produced in 1535 CE, the year after Henry VIII’s final and definitive rejection of papal authority. This Bible was no clandestine piece of contraband: it was a full-folio size lectern Bible, bidding for official status. Witness its title page, which as well as illustrating the narratives of the Old and New Testaments, also depicted an English king seated above the English royal arms, distributing the book to his kneeling lords and bishops – as the reformers prayed he would.

Henry VIII was interested in producing a Bible in English. The Bible had persuaded him that he was God’s chosen instrument to lead the English Church, and he had a touching faith that if his subjects read it, they would reach the same conclusion. A new version was produced under the pseudonym Thomas Matthew in 1537 CE. It appeared under royal license, and the king allowed it to be distributed to parish churches, not realizing that it was virtually unchanged from Tyndale’s version.

This lightly revised text, Henry VIII’s Great Bible, was made fully official and eventually printed in 1539 CE. By 1541 CE there were enough copies for all 9,000 of England’s parishes to comply with the order to buy it. On the title page of this ‘Great Bible’ (a reference to its physical size) Jesus Christ is still there, but only squeezed in at the top. The dominant figure this time is the king, now unmistakably Henry VIII himself.

The Modern Bible: The King James Version

The King James Version (KJV) English translation of the Bible was published in 1611 CE in England. The translation was generally accepted as the standard English Bible from the mid-17th to the early 20th century. The work on this Bible started in 1604 CE, soon after James’ coronation as king. At this time, various church leaders requested that the English Bible be revised. Henry the VIII’s Great Bible from about 1538 CE had been somewhat popular, but contained numerous inconsistencies and was also not readily available to the common church leader, being very large and very expensive to produce. King James approved a list of revisers allowed to work on this project. Those who were appointed worked in small groups in both Oxford and Cambridge under the supervision of Richard Bancroft, the Archbishop of Canterbury at the time. The scholars used Hebrew and Jewish sources, as well as the Geneva Bible and the Tyndale Bible, to aid in the translation. Serious attempts to relate to the original Hebrew meanings meant that this was a far more scholarly Bible than had been attempted before. This Bible was not translated from the Latin, and that, too, was a major change in translation into a common tongue. There was, however, more use in the KJV of familiar names for people than the ancient Hebrew names found in the Hebrew or Greek versions of the scriptures. So names were Jonah instead of Yonah, or Joshua instead of Yeshua.

Learning More about the King James Bible: Early Bibles in Wadham Library’s collection, with a particular focus on the King James Bible (1611), are discussed by Helen Moore, Fellow in English at Corpus Christi, Oxford, and Gordon Campbell, Fellow in Renaissance Studies at the University of Leicester. Focusing on the title page illustration, Helen and Gordon discuss what made this ‘authorized’ version of the Bible so different from its predecessors.

Since the time of the creation of the KJV, many other translations of the Bible into English have been made, most of them with much more contemporary use of the English language, since the way English is spoken has changed dramatically since the 17th century. The KJV is still much loved for the beauty of the language, even if the translations of various words are not as accurate for modern speakers of English as they may have been in the early 17th century. Students who want a clear idea of what the original Greek actually said would do best to use a more modern translation of the Bible, such as the NIV, RSV, or NRSV.

McKendrick, Scott. “The Christian Bible.” British Library, 23 Sept. 2019, https://www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/articles/the-christian-bible.

“Discovering Sacred Texts: Christianity.” Sacred Texts: Christianity, British Library, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0X5StCk6nDY.

Ryrie, Alec. “From Sacred Scriptures to People’s Bible.” British Library, 23 Sept. 2019, https://www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/articles/from-sacred-scriptures-to-the-peoples-bible.

Sutherland, Annie. “The Importance of Translation in the Diffusion of Christianity.” British Library, 23 Sept. 2019, https://www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/articles/the-importance-of-translation-in-the-diffusion-of-christianity.

“Joel Marcus – the Jewish Roots of the Christian Story.” The On Being Project, 21 May 2020, https://onbeing.org/programs/joel-marcus-the-jewish-roots-of-the-christian-story/.

Moore, Helen, and Gordon Campbell. “The King James Bible and Early Bibles.” Waldham College Oxford, 2021, https://youtu.be/Q26LydAnG-g.

Dale Martin, Introduction to the New Testament, Yale University: Open Yale Courses, http://oyc.yale.edu. License: Creative Commons BY-NC-SA . Most of the lectures and course material within Open Yale Courses are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 license. Unless explicitly set forth in the applicable Credits section of a lecture, third-party content is not covered under the Creative Commons license.

Gabel, John B. The Bible as Literature: An Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2006.

“From Jesus to Christ: The First Christians.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, 1999, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/film/showsreligion/.

- Dr Scot McKendrick is Head of Western Heritage Collections at the British Library. His recent publications include Codex Sinaiticus: New Perspectives on the Ancient Biblical Manuscript (BL Pubs, 2015) and The Art of the Bible: Illuminated Manuscripts from the Medieval World (Thames and Hudson, 2016). ↵

- Alec Ryrie is Professor of the History of Christianity at Durham University, Professor of Divinity at Gresham College, London, and co-editor of the Journal of Ecclesiastical History. He is a historian of the Reformation in England and Scotland and of Protestant Christianity more widely, and his books include Being Protestant in Reformation Britain and Protestants: The Radicals Who Made the Modern World. His book Unbelievers will be published in late 2019, and he is currently researching the early history of Protestantism’s global spread. ↵

- Dr Annie Sutherland is an Associate Professor in Old and Middle English at the University of Oxford. She works on religious literature of the English Middle Ages, with a particular focus on writing by and for women. Her published work includes English Psalms in the Middle Ages, 1300–1450. She is currently working on some prayer texts associated with a group of 13th century women living on the borders between England and Wales. ↵

- Joel Marcus is an author and Professor of New Testament and Christian Origins at Duke Divinity School. ↵

the language or dialect spoken by the ordinary people in a particular country or region.

"she wrote in the vernacular to reach a larger audience"

the authorized and final list of books considered to be part of the Bible