20 The Epistles

An epistle (/ɪˈpɪsəl/; epistolē,) is a written piece directed or sent to a single person or to a group of people, usually as a formal letter focused on instruction and the passing on of specific information.

There are 21 epistles specifically in the New Testament canon, and there are also a number of other epistles that are mentioned in various Christian writings which were lost to the church over the centuries. Of the 21 canonical epistles, 7 are considered to be uncontrovertibly written by Paul. Several more of the letters are considered to have possibly been written by Paul, but equally as possibly to have been written by a follower of Paul, using his theology and wording style. And other letters have traditionally been attributed to Paul, but the authorship is clearly disputed and generally not considered to be Paul’s writing.

Those epistles traditionally attributed to Paul (7 for sure, and 7 more by tradition) are known as the Pauline epistles, and the other 7 canonical epistles are known as catholic (small c) or “general” epistles. There are traditions concerning the authorship of the non-Pauline epistles, but almost nothing is known about the authors of those general letters. The epistles are not listed in the New Testament in order of composition, but to some extent, in order of length.

Who is Paul?

It is difficult discussing the historical Paul. Paul, known as Saul early in the book of Acts, of the tribe of Benjamin, was eventually called Paul after his conversion to Christianity, and was clearly Jewish. Paul grew up, according to tradition, as a Diaspora Jew, meaning as someone who didn’t live in Israel, but in some other place outside of the home nation. He is called Paul of Tarsus, a city in what is now Turkey, which would have been a Greek speaking city during the Roman Empire. Paul was considered a tentmaker or leather worker by tradition, so he would have been able to support himself during his stays in various cities, and he was then easily able to communicate with the artisan populations of those Roman cities. Paul was also a Pharisee by faith, which according to Shaye I. D. Cohen[1] is

“… a scholarly group or a group of Jews who, as Josephus the historian says, had a reputation as the most meticulous observers of the ancestral laws. So here is a group which claim expertise [in] understanding the Torah of Moses and claimed expertise in the observance of the laws.”

So according to his faith of origin, Paul was a devout, conservative, and zealous Jew. As he wrote to his Christian congregations, post-conversion, Paul came to write about himself as following in the line of Jewish prophets. Jewish prophetic tradition talks about prophets having a call to speak a very specific message for God. Paul portrays himself as a Jewish prophet, using prophetic language in his preaching and writing, likely because Paul learned prophetic language from his studies. Paul’s message from God that he was to deliver to others, he felt, was to talk about Jesus. Paul’s message was not always the message that Jesus himself spoke, however.

Paul’s message to the gentiles seems to come from his own interpretation of the Jewish scriptures, particularly from the prophet Isaiah. Isaiah talks about a time in the future when the messiah will finally arrive. When that happens, says Isaiah, there will be a light given to all nations about the God of Israel, and the Jews will become– “a light to the gentiles.” Paul seems to view the messianic age as having arrived with the ministry of Jesus, and that because of this reality, there is an opportunity for bringing gentiles–“the nations”– into the kingdom of Israel’s God. He firmly believed that bringing gentiles to a belief in the God of Israel was one of the hallmarks of this messianic age.

Paul isn’t writing scripture as he writes to his churches. When Paul refers to scriptures, or to the Bible, he means the Hebrew Scriptures, probably the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures called the Septuagint.

Paul writes ordinary letters to real people dealing with some thorny theological questions, but in these letters Paul is mostly just trying to give helpful advice, moral instruction, and encouragement for stepping into the kingdom of God. He had some very hard things to say to people at times, and some of his rhetoric was specific to a very particular congregation. Without knowing some of the context in which Paul was writing, his work can be misread. For the most part, Paul focuses his writing on the importance of the death and resurrection of Jesus, and on the the imminent coming of the end times. Paul believed that the end times were happening any day, and that the way one prepares for the end of time is to be a decent person, usually within the confines of Jewish ethics. Ethical instruction is very common in Paul’s letters. His ethical instruction centers around this issue of how one lives a life worthy of God, in anticipation of the end time that Paul believes is just around the corner. .

No one knows precisely what eventually happened to Paul at the end of his travels, after he arrived in Rome under arrest, having been brought there from Jerusalem. Tradition holds that he preached in Rome for a couple years after his arrival, at least, and that he was finally martyred in Rome in about the year 64 CE. This was after the great fire of Rome. According to some historical writing, the emperor Nero seemed to have blamed the fire in Rome on the Jews and the Christians, not because they had started it, but because Nero needed a scapegoat for his own actions. Killing Paul might or might not have been connected to the Christian persecutions.

Peter and James seem to have died about the same time as Paul, so that by the mid sixties the first generation of Christian leaders are gone.

Some fun following Paul

A fairly simple but very approachable way to follow Paul and his journeys would be through this popular YouTube series called In Pursuit of Paul: The Apostle. Dr. Constantine Campbell has made videos of various aspects of Paul’s travels and interactions with the churches. In Pursuit of Paul

Southern Netherlandish or Northern France; Sculpture-Alabaster circa 1450 –70 CE

Paul and the beginning of Christianity

There is a great deal of tradition–oral and written–that shows Paul as the founder of Christianity. Some scholars have said that Jesus was not really the founder of Christianity, but that Jesus was a moral prophet, an extraordinary teacher, healer, and preacher. Whether the early church believed Jesus was the messiah, an incarnation of God, just human or also divine was debated at the time. But Jesus clearly had no intention of founding a new religion. He was working within Judaism.

Paul was the one who founded Christianity more formally as a new religion. He was the one who built churches, he was the one who came up with the dogmas and doctrines of Christianity, he is the one who preached what the central aspect of faith really is, according to his own beliefs. Paul states that Christianity is faith in a crucified Messiah who is then raised by God, and it is faith in this risen Christ that is the foundation of Christianity. All of these things, scholars and historians have said, make Paul more the founder of Christianity then Jesus is.

The early church didn’t think of Paul as a great theologian, however. In the early church Paul is depicted in art and in literature as the great martyr, whose head was cut off in Rome. As time went on, however, Augustine and eventually even Martin Luther saw in Paul and in his writing a man who was trying hard to be righteous, to keep the Jewish law. They understood Paul as a person who experienced his life as trying to live up to the requirements of God that are found in the Torah. They also saw Paul writing about how he just couldn’t do this ethical living all on his own.

For Luther, Paul represented this example of a human psychological struggle, of someone trying to be righteous, and trying to earn his righteousness by his works. Luther discovered, when reading Paul more closely, that Paul finally preaches that humans will be saved by grace through faith, not by the works or rituals that they do. Paul came to realize that humans could not “save themselves”. Protestants began to say, then, that works don’t matter, that all those historic Roman Catholic requirements for ritual and other behaviors are not where salvation comes from, but that salvation simply comes from faith and God’s grace. The anguished Paul who finally discovers God’s grace has been the key to theology in Protestantism.

Beginning in the nineteenth and into the twentieth century, historians and scholars became interested in the reality that Paul’s letters do not sound like the message being delivered by Jesus in the Gospels. Jesus was preaching about finding, living in, and recognizing the Kingdom of God. Paul, on the other hand, preaches about Jesus as the King, Jesus as the Messiah. Jesus talked about God. Paul talked and wrote about Jesus. This change shifts the story of the early Christian church.

In some ways, Paul really changed the religion of Jesus. Jesus was a great moral and religious teacher, but he didn’t teach about the Christian doctrines such as the trinity, hell and heaven, the virgin birth, the incarnation of God, and so on. Paul was actually the founder of modern Christianity because he redirected the message that the historical Jesus taught.

There are many scholars, theologians, and believers who are strong supporters of Paul, his writing and his beliefs. There are also various people who have struggled with Paul’s role in the Christian church, in society in general, and have not liked his teachings. A few examples can show the issues people have had with Paul and his teachings.

Friedrich Nietzsche was a philosopher who was not particularly enamored with Jesus, but who really disliked Paul and all he stood for and taught. Nietzsche said,

“The glad tidings,” [that is the Gospel, the good news], “were followed closely by the absolutely worst tidings, those of St. Paul.”

The cross was Paul’s invention symbolizing Christianity and that cross is what made Christianity, says Nietzsche.

George Bernard Shaw said this about Paul,

“No sooner had Jesus knocked over the dragon of superstition than Paul boldly set it up on its legs again in the name of Jesus,”

and Shaw said this as well,

“Paul is the true head and founder of our reformed church, as Peter is of the Roman church. The followers of Paul and Peter made Christendom while the Nazarenes were wiped out.”

The religion of Jesus, according to Shaw, disappeared from the earth, and all that we were left with is this shell called Christendom.

US president Thomas Jefferson wrote that Paul was:

“the first corrupter of the doctrines of Jesus.”

There are opinions, studies, and thousands of books and articles about Paul, his teaching, his writing, and these come to students of the Bible with diverse perspectives. Some information concerning Paul is completely unverifiable. Some of the ideas about Paul’s work are emotional. Paul’s writing has been studied in various languages, with microscopic attention to detail. No matter what the scholarly or personal perspective is on Paul, historical context is critical for understanding each of the epistles.

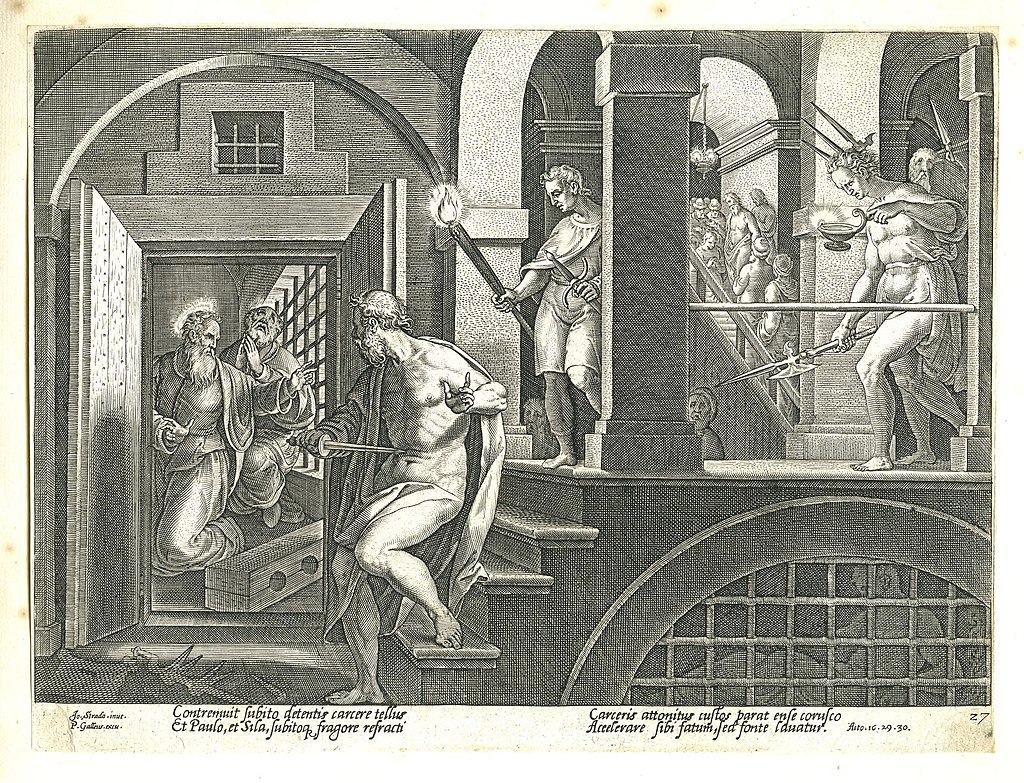

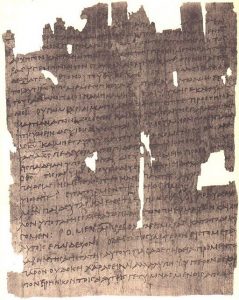

between 1591 and 1666 CE

What does Paul say about himself? What about the contradictions with stories found in Acts?

There are only a few basic details to be known about Paul.

In Philippians 3:5-6, Paul tells us that he was of the tribe of Benjamin and that he was a Pharisee. Paul is one of the only people calling himself a Pharisee whose writings history actually possesses. He says that he was a persecutor of the church before he became a follower of Jesus, and he implies that this was out of zeal for the law. Paul started off as a very law abiding, zealous Jew, and he says in Philippians that he was righteous under the law. Paul also never says that he had stopped being a Pharisee–he still claims that as part of his identity.

Some of the things about Paul that people think they know as historical facts only come

from Acts. What are those?

- He was brought up and educated in Jerusalem at the feet of Gamaliel, a very famous first century rabbi. Only in Acts does Paul says that about himself, however. Is this something that Luke put in there, or is it part of oral tradition?

- His original name was Saul, according to Acts. Paul never tells us that himself. It is not unlikely, as a lot of Jews then might have both a Hebrew name and a name used in whatever language they spoke every day, so Paul may indeed have had two names. But he never calls himself Saul in his letters; that’s a name that he is given in Acts.

- Acts says that Paul was born a Roman citizen. It is a pretty impressive thing for a Jew in the eastern part of the Mediterranean to be a Roman citizen, and in the first part of the first century that would have been fairly unusual.

- In Acts Paul is portrayed as speaking Hebrew fluently. He gets up in Jerusalem and gives whole long speeches in Hebrew. Paul never in his letters gives any indication that he spoke Hebrew. Greek seems to be his first language, and there is no direct indication that he spoke Hebrew. All his writing is in Greek.

Then one last very important statement to keep in mind: according to Acts, Paul’s normal modus operandi, his way of operating, was to go to a town and go to the synagogue first and, only after he was rejected in the synagogue, would he then go preach to the Gentiles.

Acts 17 gives the account of when Paul first went to the Thessalonica, at least according to Acts. Thessalonica is an important Roman city in Macedonia, home area of Alexander the Great, and Philip his father, which is now considered by the Romans part of Achaia or Greece. It’s a Greek speaking area but Thessalonica is a Roman kind of city, right on a major highway running east to west.

Here is the way Acts describes Paul’s getting to Thessalonica. Read this. Then go to 1 Thessalonians and see if a reader can confirm any of the Acts material from Paul’s own description about what happened in Thessalonica.

Start with Acts 17:1

After Paul and Silas had passed through Amphipolis and Apollonia, they came to Thessalonica where there was a synagogue of the Jews. And Paul went in, as was his custom, and on three Sabbath days argued with them from the scriptures, explaining and proving that it was necessary for the Messiah to suffer and to rise from the dead and saying, “This is the Messiah, the Christ, Jesus, whom I am proclaiming to you.” Some of them were persuaded and joined Paul and Silas, as did a great many of the devout Greeks, and not a few leading women.

But the Jews became jealous, and with the help of some ruffians in the marketplaces, they formed a mob and set the city in an uproar. While they were searching for Paul and Silas to bring them out to the assembly, they attacked Jason’s house. When they could not find them they dragged Jason and some believers before the city authorities shouting, “These people who have been turning the world upside down have come here also, and Jason has entertained them as guests. They are all acting contrary to the decrees of the emperor, saying that there is another king named Jesus.” The people and the city officials were disturbed when they heard this, and after they had taken bail from Jason and the others, they let them go. That very night the believers sent Paul and Silas off to Berea, and when they arrived they went to the Jewish synagogue.”

They are arrested, they have to post bail, and then during the night the believers get the two men out of town. Once free, they go to Berea, and again, Paul and Silas go first to the synagogue.

That is the general account from Acts about that event.

Now look at 1 Thessalonians. What does 1 Thessalonians say about how Paul worked as a missionary? Paul was trying to convince Gentiles in his era to accept that Jesus of Nazareth, whom they had never heard of before, and who had been executed by the Romans way off in Jerusalem, was not only the new king of the Jews and raised from the dead, but that now this Jesus was going to be king of the whole world. Paul thought and taught that even Gentiles should know about and revere this King Jesus. He was trying to convince the people that they should all worship the God of Israel, precisely because the God of Israel had raised Jesus from the dead.

Here’s what he talks about in 1 Thessalonians. He starts with this long thanksgiving.

Paul, Silvanus [Silvanus is the Latinized name of Silas so we’re talking about the same person that Acts called Silas– called Silvanus here], and Timothy to the church of the Thessalonians, and God the Father and the Lord Jesus Christ, grace to you and peace. We always give thanks to God because our message of the Gospel came to you not only in word but also in the power of the Holy Spirit, full conviction just as you know what kind of persons we preach among. You became imitators of us in the Lord in spite of persecutions you received the word with joy inspired by the Holy Spirit. You became an example to all the believers in Macedonia and Achaia. For the word of the Lord had sounded forth from you not only in Macedonia and Achaia, but in every place your faith in God has become known, so that we have no need to speak about it.

For the people of those regions report about us what kind of welcome we had among you and how you turned to God from idols, to serve a living and true God and to wait for his Son from heaven, whom he raised from the dead, Jesus, who rescues us from the wrath that is coming.

Look at who it is that Paul is talking to here. What kind of people were they before they became followers of Jesus? Is Paul talking to Jews? Clearly not; here Paul is talking to Gentiles because he says, “You turned from idols to serve the living and true God.” Jews did not worship idols. So these are obviously Gentiles Paul is addressing in 1 Thessalonians.

In Chapter 2:9, Paul gives another clue,

“You remember our labor and toil, brothers. We worked night and day so that we might not burden any of you while we proclaimed to you the Gospel of God. You are witnesses in God also…”

One of the things that Paul wants to insist is that he, Silas, and Timothy didn’t live off handouts from the Thessalonians. He is insisting that they earned their own keep, practiced their own trade. Whether Paul was a tent maker or not, in I Thessalonians there is a definite indication that Paul was a manual laborer, that he worked with his hands.

“We worked night and day so that we might not burden you. You are witnesses in God also, how pure, upright, and blameless our conduct was toward you believers. As you know we dealt with each one like a father with his children.”

Clearly they practiced manual labor when they were there. Now look at 2:14:

“For you, brothers, became imitators of the churches of God in Christ Jesus that are in Judea. For you suffered the same things from your own compatriots as they did from the Jews, who killed both the Lord Jesus and the prophets, and drove us out. That displeased God and opposed everyone by hindering us from speaking to the Gentiles so that they may be saved. Thus they have been constantly filling up the measure of their sins but God’s wrath has overtaken them at last.”

Paul is saying that in Thessalonica the people were persecuted just like the followers of Jesus were persecuted in Judea. Who is persecuting these followers of Jesus in Thessalonica? Compatriots; in other words, other Greeks. They’re not being persecuted by Jews, they’re being persecuted by their fellow Greeks. They experience persecution once they decide to follow this Jewish Messiah. Jews are not mentioned in this account, so the people in Thessalonica are getting this reaction from their fellow Greeks.

In other words, it’s pretty clear that Paul is addressing a church that’s composed of all Gentiles. Now notice how this does not fit the narrative of Acts. According to Acts, Paul goes first to the synagogue, he preaches to the Jews, some of them believe including leading women, and he forms the nucleus of his group with Jews, and then he adds onto that nucleus Gentiles. This is the pattern described time and again in Acts.

In 1 Thessalonians the story is more clearly laid out. There Paul gives a better idea of what actually happened, which was that Paul founded this particular church from Gentile believers alone, and when they experienced persecution it wasn’t from the Roman authorities and it wasn’t from Jews, it was from their close neighbors. When historians and scholars look at what’s going on in Thessalonica, it is important to look closely at 1 Thessalonians and not just depend on Acts to tell the story. This will be the case for all the epistles–they will be more accurate about what happened with Paul, what Paul thought, and what Paul taught, than the accounts found in the book of Acts.

There are maps of Paul’s journeys below, and although the titles are in Italian, the locations are clear. You can slide the button on the bottom of the maps to shift from one to the next.

Paul as the Apostle to the Gentiles

There are seven letters that Paul wrote himself, work that most scholars believe is actually authentic to Paul. Some other letters are written in his name–by a secretary, a follower, or someone who could speak with confidence for Paul. There is more material about Paul than almost anyone else in the New Testament, but there is still quite a bit of debate about what is historical information about Paul and what is later legend. This debate just means that these particular 7 letters are the letters that almost all scholars will agree Paul wrote.

The undisputed letters are Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, 1 Thessalonians and Philemon.

Decades after Paul’s death several others were written, probably by a follower of Paul, or someone wanting both the prestige of his name, but also to honor Paul’s ideas. These letters would include 1 and 2 Timothy and Titus. They are also called the Pastoral Epistles because they show Paul trying to teach both Timothy and Titus how to be good pastors of a church.

The last set of letters sometimes attributed to Paul are tricky to determine for authorship. Some scholars will accept 2 Thessalonians as being written by Paul; but more scholars doubt that this is the case. Even fewer scholars will accept Colossians as being written by Paul, and for most scholars the letter to the Ephesians was clearly written by someone who used Colossians as a model, but that it was not Paul who wrote it.

One thing that becomes obvious in the narrative of the epistles is how different house churches start organizing themselves. Paul, in his letters, will repeatedly address certain people by name, and he greets them and then greets the church that meets in their house. The people he names are considered the patrons, the paterfamilias, of the house church. This structure, showing a group that is meeting in the home of their leader, who is then considered in charge of the congregation, is loosely based on the structure of a Roman household of the time. It would have been familiar to the people as a way to organize, and it worked fairly well when the groups were small.

Main Ideas in the 7 undebated Pauline Epistles

What did Paul teach in his epistles? He certainly had a broad focus on teaching about Jesus as the risen Christ, God come to earth to save humanity. He also taught an imminent coming again of the savior in an “end times” era.

But each of the epistles had some special ideas that are key elements of Paul’s writing. A little bit of context for at least the 7 epistles thought to be Pauline in origin might be useful.

I Thessalonians

So what did Paul say to the Thessalonians?

- Paul taught them to turn from idol worship and polytheism. A fundamental message that Paul spread to people all over the region was that idols are not gods. They were to stop worshipping these stones, rocks, and statues, and start worshipping the God of Israel. The God of Israel is the only true God, the only living God, and all the rest of these are nothing.

- Paul taught them about the concept of a messiah, and to accept the kingship of Jesus Christ as God’s Son and the Jewish Messiah.

- He emphasized that Jesus was coming back again to reign within their lifetime, and that they should stay alert, and not worry about the wrath of God that will descend on earth with this coming apocalypse, because their belief will save them from that wrath. This is not a warning about being saved from hell, is nothing to do with life after death, but about being saved from God’s wrath during a second coming.

- Paul also reassured them and says that they should not grieve for people who die before this apocalypse happens, because the believers who have died will leave their graves and join in. The dead will not miss out.

- God’s kingdom will be finally be established with Jesus as king on earth.

- And finally, Paul is telling them that while they await the salvation of Jesus to come from heaven in the near future, they should avoid certain Gentile behaviors, which he lists in some detail.

- The behaviors in particular named in Thessalonians that were considered important to avoid were what he considered “sexual impurity” (and this is just for men, by the way–it would not have occurred to him to discuss this about women in either Jewish or Gentile cultures) which would include adultery, masturbation, homosexuality, having the woman on top of a man, using a dildo, any kind of oral sex whether it was homosexual or heterosexual, and so on. Any sex that Jews believed should not be done and that Gentiles typically did do, Paul is very much against.

All through this letter, the language in the Greek is singularly pointed at men. At least at this stage in Paul’s career, it is possible that he really did see these small churches as being primarily for men, who in Judaism were also the scholars and leaders. What this group in Thessalonians would have been, at least at first, was a male group of Greek speaking, gentile, manual laborers. They have been initiated into a new group that demanded adherence and loyalty to the God of the Jews and an expected Jewish Messiah. In other words, this is an apocalyptic Jewish sect of Gentiles.

Now some of Paul’s other letters show that his churches, even if they started off as a collection of Gentile men, became a lot more complex later on.

Galatians

Paul founded several house churches in the area of Galatia. There’s some debate about exactly what part of Asia Minor he’s referring to because there are different parts that were called Galatia. Of course the word “Galatia” probably just comes from the word for “Gaul”. The Gauls were tribes, first in what is now France nearby surrounding areas. The Gauls invaded the eastern parts of the Mediterranean, so eventually a part of Asia Minor that is modern day Turkey was called Galatia. Paul worked creating churches in this area, and the churches there were all Gentile churches. There is no record that he had any contact with Jews in the area, and there is no record in the letter to the Galatians that he is addressing any Jews. The letter to the Galatians is not directed to one house church or even one town, so this is a circular letter that would have gone around to different towns in the region.

A serious issue for the Galatians concern the keeping (or not) of the Jewish ethnic laws. These laws were originally written for Jews, are still enforced in various congregations, and some early gospel preachers are saying that if the new believers want to follow the God of Israel, then they must keep the Jewish laws. This kind of message to the gentiles sends Paul right over the edge. He writes the epistle to the Galatians trying to convince the towns in this area not to accept this more Jewish-based approach to faith, and this is where Paul is coming from in this rather angry and vituperative letter.

Issues that arose in the early church in general included:

- Does one have to become Jewish in order to then be a follower of Jesus?

- Does this mean keeping Jewish law?

- Who decided what was true–Peter, James and John, or other teachers such as Paul, who were not a part of the original 12 disciples?

- Is a person is justified by works of law or through faith in Jesus Christ?

- Paul claims that even with Abraham, it was faith that justified him, not the law. The law came about to keep people from sinning, according to Paul.

- The letter then falls into 3 parts:

- Paul’s relationship to the Galatian churches in the past and his connection to the original disciples in Jerusalem

- a rather densely argued set of ideas about acts of law versus faith in Christ

- Christian liberty and morals

No one really knows what happened after Paul sent his letter to the Galatians. Did he convince them that he was right and the other people who were teaching them to obey the law were wrong? There are no other letters to the Galatians available to scholars. It has been pointed out by some scholars that Paul never talks about the area of Galatia again to any of his other churches in other areas. This has led some people to suggest that maybe Paul lost the battle in the churches of Galatia, and, therefore, he just didn’t deal with them anymore after that.

Philippians

Philippi was a city in Greece, north and slightly east of Thessalonica. The letter to this church is not one of chastisement, and is much more supportive and affectionate than most of Paul’s other letters to congregations. It is likely that Paul wrote multiple letters to the Philippians, but only one survives.

Paul is in prison at the time of the writing of this letter, and he is not sure what the outcome of this will be. He uses his own situation, as well as the struggles of the people in Philippi, to point out that self-surrender in the face of suffering will bring them joy. He encourages unity in the face of all adversity, and that by doing so, they will find joy in the midst of sorrow. Paul refers to a hymn that was likely composed before Paul wrote to the Philippians, and that Paul uses in the letter to his church to offer encouragement.

Philippians 2: 5-11

Let the same mind be in you that was in Christ Jesus,

who, though he existed in the form of God,

did not regard equality with God

as something to be grasped,

but emptied himself,

taking the form of a slave,

assuming human likeness.

And being found in appearance as a human,

he humbled himself

and became obedient to the point of death—

even death on a cross.

Therefore God exalted him even more highly

and gave him the name

that is above every other name,

so that at the name given to Jesus

every knee should bend,

in heaven and on earth and under the earth,

and every tongue should confess

that Jesus Christ is Lord,

to the glory of God the Father.

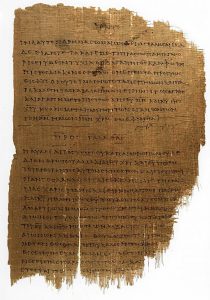

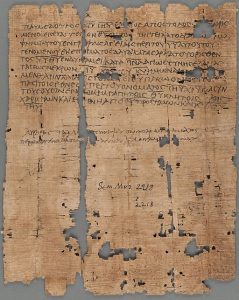

circa 300-350 CE

Romans

Paul did not found the church in Rome; it grew up on its own. According to Roman Catholic tradition, Peter founded the church in Rome, but that is tradition and there is really no historical data to prove it. The church in Rome was likely started by anonymous Jews who happened to hear about Jesus, and who then went to Rome and started little house groups of Jesus followers on their own. Then some apostles came to them later, just like Paul seems to have gone to Rome later. The Roman church, at the time Paul is writing this letter, is by this time no longer a purely Jewish group. They now seem to be predominantly Gentile, with some Jews also in the churches. And The Roman church is not one house church, but several different house churches that meet in different people’s homes. Some of them had more Judaism in their make-up than others. But the overall church in Rome is by that time mostly gentile, and when Paul writes Romans he directs his rhetoric to gentiles. He does greet the Jews who are there that he knows. But looking through the rhetoric of Romans, more scholars are convinced that the main recipients of Paul’s rhetoric is gentile believers in Jesus.

So why is Paul writing to a church he did not found?

Look at Romans 15:22:

This is the reason I have so often been hindered from coming to you. But now with no further place for me in these regions, I desire, as I have for many years, to come to you when I go to Spain. For I do hope to see you on my journey and to be sent on by you once I have enjoyed your company for a little while.

Paul writes in a way that sounds like he has done everything he can in the East, in Greece and Asia Minor. He acts like his work there is done. So he is taking off to the west. It is exaggerating what he has accomplished, but in his mind by starting a few house churches in major cities, he has done the first job of evangelization that he saw himself called by God to do. Now he is looking to the west, and he wants to go to Spain, and on his way to Spain he is going to stop in Rome. He is saying in this letter that he wants a contribution from the Roman churches, with both symbolic and financial support. Rome is the center of the earth for the Romans, and he sees himself as the Apostle to the Gentiles of the whole earth. So what more likely place for him to go than to Rome on his way to Spain?

The big Protestant reading of the letter to the Romans set Romans as the central book of the Bible, focused mainly on individual salvation. Paul wrote that people needed to recognize that they would not be saved by works, or by anything that they do. People are not saved by Jewish law, not saved by rules or ritual, but are saved by putting faith in Jesus, accepting Jesus as Lord and Savior. It is a doctrine of individual salvation by faith, and that is the reason Paul wrote the epistle to the Romans. This is the central message of Romans: very individualistic, very doctrinal, very theological.

That reading of Romans from the previous paragraph has been severely challenged in the last forty years. Scholars are starting to say that it is not the first few chapters of Romans that constitute the most important part of Romans, which has always been the heart of the Protestant interpretation. Scholars now look to the end of Romans, chapter 9-11, where the real point of Romans is, and it is not about individual salvation. This passage is about the relationship between the nations. “Gentiles” is just a term that Jews used for all the nations except themselves in the ancient world. So in Paul’s text “nations” refers to the non-Jewish nations. What then is the relationship of the other nations to Israel and the God of Israel? Paul quotes Jewish scripture to enforce his belief that at the end of time gentiles would become people of Israel’s God, a common idea in Jewish apocalypse concepts. The Messiah will overthrow the oppressors of the Jews, and the Messiah will bring in all the other nations to the temple in Jerusalem. They will all then worship the God of Israel. This idea is found in both Isaiah and Hosea. So Jewish scripture itself gave Jews of Paul’s day the idea that the apocalyptic end would bring all the nations into their faith and tradition. The Messiah had already come, according to Paul, so his whole mission is this end time scenario of bringing Gentiles into the messianic era.

Paul believed that he was the Apostle to the Gentiles to bring them into faith in Israel’s God. Then he somehow believes, although he doesn’t say how it is going to happen, that somehow God and God’s miraculous mercy is going to figure out a way to even bring all of Israel to faith in Jesus. All Israel, he says, will be saved.

There is also a fair bit of discussion about the law and what that Jewish law means to a mixed congregation, about gentiles not looking down on believers of Jewish origin, about living an ethical life, and about the Roman churches living a life of justice for all. Romans, like all of the epistles, has multiple functions. The traditional Protestant “salvation” focus and the more recent focus on the “nations” are the big ideas in the letter, but there are the usual other ideas included.

I and II Corinthians

The situation with Paul’s church in Corinth is very different from the situation with the church in Thessalonica. The letter of I Thessalonians shows us a church that is in its infancy. I Corinthians shows us a church with some growing pains, so the reader can tell that the members of this church are not all brand new Christians. I and 2 Corinthians and give several snapshots of the development of the Corinthian church and Paul’s relationship to it.

- In I Corinthians discussion of what resurrection looks like is important. There is a big issue of earthly bodies contrasted with heavenly bodies for the resurrected people in the future.

- The focus on the cross is emphasized in this letter.

- There is obviously conflict in Corinth depending on who is talking to the people involved there. There may have even been more than one house church in Corinth, and they believed different things. This is a problem, and some of the problem may have happened because there are differing social statuses, education levels, and employment status in the membership of the churches.

- In 1 Corinthians Paul is concerned with controversies that have been dividing the church, most probably along those social status lines. The wealthier members are not always being concerned with how the poorer members are able to function in the church. Issues for them include:

- Whether one should eat food sacrificed to idols,

- How one ought to conduct oneself sexually, including the use of prostitutes,

- about whether to get married, about relations with step-family, and about divorce

- Behavior during church, such as the practice of speaking in tongues, women veiling themselves, how to eat the Lord’s Supper,

- How to handle disputes–in or out of court?

- 2 Corinthians shows that these specific issues seem to have been resolved by the time Paul gets to writing to 2 Corinthians, although Paul clearly has other problems to address.

- 2 Corinthians 10-13 ( which is actually most likely a separate, 3rd letter to the church) presents Paul in a defensive posture, struggling to justify his position over and against the new “super apostles” that have infiltrated the Corinthian church. Paul is forced to defend himself from charges that he is uneducated, weak, and powerless, and therefore not much of an Apostle.

- 2 Corinthians seems to be a composite of pieces of several lost letters, with ideas centering around affliction and consolation. This idea is just part of the rather disjointed discussion of whose teaching will dominate belief in Corinth–Paul’s or that of other, newer preachers.

Looking at Corinth: The Center of Corinthian Culture and Tourism Development has some excellent photos and information about Ancient Corinth. It includes 2 videos about the letters I and II Corinthians–and they are good basic summaries of the content of those letters.

You can see various photos, read short articles, and hear 2 very solid mini-lectures on the content of the letters to the Corinthian church at this site. Click on Apostle Paul in the tool bar at the top of the page. Start here with photos, and then go check out more on Paul. Explore Corinth

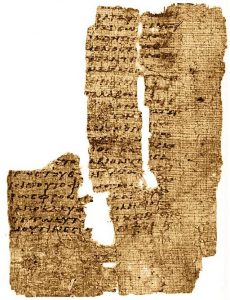

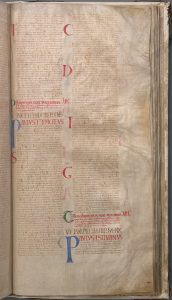

Medieval

Philemon

Paul is again writing from prison, but the location and situation of that imprisonment is not clear from the context of the epistle to Philemon. Paul has been joined in prison by a person named Onesimus, the slave of a man named Philemon. While Onesimus is with Paul, he has converted to belief in the ideas of Christianity. While it is not clear how Onesimus came to be with Paul in prison, it is clear that the letter addresses sending Onesimus back to his owner.

There have been varied interpretations of what Paul is saying to Philemon, and because Paul is a touch unclear, it is being left up to Philemon and the reader to understand what the “good deed” is that Paul is asking Philemon to perform. Is Paul asking that Philemon free Onesimus? Is he asking that the slave be forgiven for running away? Is he asking that Onesimus be allowed to serve Paul while Paul is in prison? It is not clear. It is an interesting addition to the canon, this very specific and personal letter. It was misused, however, in support of slavery over the centuries.

The Other Epistles

Ephesians, Colossians, and 2 Thessalonians are clearly Pauline in thought and intent, and while dubious in original authorship, come from the Pauline school of theology. Ephesians holds up that key Jewish apocalyptic idea of the unity of Jews and Gentiles. Colossians identifies the ongoing connection of Jewish ethics and ritual with the new Gentile church as part of the author’s ideas. 2 Thessalonians has a generally encouraging tone, telling the people to imitate the teacher, but also has some ideas that differ from I Thessalonians. Here the idea of imminent apocalypse is, instead, described as a time of delay and struggle before the coming again of Jesus. The believers are to prepare for ongoing life in this world, and not just wait for the second coming to be any day. This is part of what makes scholars wonder about the authorship.

The Pastoral Letters are 1 and 2 Timothy, and Titus. This is a later title applied to the letters, from some time in the 18th century. They describe Paul’s exhortations to these two men about their ministries among the early churches. The disagreement about who wrote these is based on the Greek vocabulary and the style of writing, both of which differ from the known Pauline epistles. These letters focus on the problems with increased institutionalization of the churches, and this set of problems fits better with a later date of composition, perhaps very late 1st century. They favor a focus on increased obedience to structure and adherence to tradition within the church.

Hebrews is considered an anonymous letter to churches with an emphasis on Jesus as the high priest of Judaism. There is use of various Hebrew scriptures in this letter, showing the ongoing importance of Judaism within the Christian community of faith. Clearly the community addressed has suffered hardship, and some within it have lost or renounced their faith. Generally scholars see this letter having 4 sections:

- the word of God spoken through Jesus, the Son

- Jesus as the eternal high priest

- faith as insight into heaven beyond the law

- practical advice

James, I and 2 Peter, I, 2 and 3 John, and Jude are short letters at the end of the section of epistles. James is attributed to the brother of Jesus, and consists of moral imperatives to a Jewish Christian congregation by combining a sermon by James with materials created later to connect with that sermon. It is still more within the Jewish wing of the Christian community.

The two letters given Peter’s name are not likely even by the same authors. The language is far more sophisticated than that which would have been used by a Galilean fisherman, and the materials come from later in time, as well. I Peter is encouragement to churches in Asia Minor who are struggling with ostracism because of their conversion to Christianity. 2 Peter uses some apocalyptic language that acknowledges the problems of earth and the hope for God’s reign, and encourages the reader to participate in God’s promises.

The three letters with John’s name attached are likely written about 100 CE or a bit later, but clearly with the Johannine approach and theology found in them. There may have been one writer, or there may have been more than one, but they kept their ideas consistent. Dissidents in belief are addressed here, some seeming to border on gnostic ideas of separating the divine from the human Jesus before death, so that the divine did not suffer. The Johannine connection between Christology and salvation (which states that Jesus is fully divine and identical to the Father) is maintained.

Jude is the last epistle in the Bible. Jude is the brother of James and Jesus. The letter has been date to any time between 50-100 CE, with some hints that it is later, but still written before I Peter, whose author quotes Jude. It is not altogether clear who the recipients are, but the letter encourages the readers to keep themselves in the love of God, and uses a whole variety of Hebrew scriptural references to support these exhortations. Jude ends the section of the epistles with a singularly lovely doxology:

24 “Now to him who is able to keep you from falling and to make you stand without blemish in the presence of his glory with rejoicing, 25 to the only God our Savior, through Jesus Christ our Lord, be glory, majesty, power, and authority, before all time and now and forever. Amen.”

Turner, Geoffrey. “Pauline Christology: An Exegetical-Theological Study. By Gordon D. Fee.” Heythrop Journal, vol. 50, no. 1, 2009, pp. 147–148., https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2265.2009.00438_31.x.

“Ancient Corinth.” Explore Corinth, Center of Corinthian Cultural and Τourism Development, https://explorecorinth.gr/portfolio/ancient-corinth/.

Meeks, Wayne A, et al. “Paul’s Mission and Letters | from Jesus to Christ – the First Christians | Frontline.” Frontline: from Jesus to Christ, Public Broadcasting Service, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/religion/first/missions.html.

Attridge, Harold, et al. “The Diversity of Early Christianity | from Jesus to Christ – the First Christians | Frontline.” Frontline: from Jesus to Christ, Public Broadcasting Service, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/religion/first/diversity.html.

May, Herbert G., et al. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha: Revised Standard Version, Containing the Second Edition of the New Testament and an Expanded Edition of the Apocrypha. Edited by Michael D Coogan, Oxford University Press, 2007.

Gabel, John B. The Bible as Literature: An Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2006.

Dale Martin, Introduction to the New Testament, Yale University: Open Yale Courses, http://oyc.yale.edu. License: Creative Commons BY-NC-SA . Most of the lectures and course material within Open Yale Courses are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 license. Unless explicitly set forth in the applicable Credits section of a lecture, third-party content is not covered under the Creative Commons license.

Campbell, Constantine. “In Pursuit of Paul: The Apostle.” Our Daily Bread, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLPOUA7GLxXIE8fVIvSB5zex_puERrXYkD.

- Samuel Ungerleider Professor of Judaic Studies and Professor of Religious Studies Brown University ↵