12 Psalms

Looking at the Psalms

Introduction

The Book of Psalms contains the largest collection of religious poetry in the Bible– 150 poems, most of which are prayers of some sort.

The term “Psalms” comes later in time (compared to when the prayers were written) from the Greek word, psalmoi. It refers to religious songs that were thought to be performed with the accompaniment of a psalterion, a stringed musical instrument. The Hebrew term for the Psalms is tehilìm, which means to shine, or to praise.

The Psalms were collected into one book in the post-exilic period, somewhere in the fifth or the fourth century BCE. But many of these psalms are thought to have been used in the era of the first temple services, and so date from early pre-exilic times, during the time of the Davidic kings. Most of the Psalms tell very little, however, about the time and circumstance of their composition. Intent for a number of them is clear from what the psalms say. A few were obviously used at royal coronations or royal weddings, and so were written and used when Davidic kings still ruled. Others are general laments or general praise songs, and could have come about for almost any ritual or occasion of worship. A number were clearly written for the use of pilgrims.

Scholars divide the Psalter into five main collections. Each of these concludes with a doxology that indicates that it is the end of that section.

- Book 1 (Psalms 1–41)

- Book 2 (Psalms 42–72)

- Book 3 (Psalms 73–89)

- Book 4 (Psalms 90–106)

- Book 5 (Psalms 107–150)

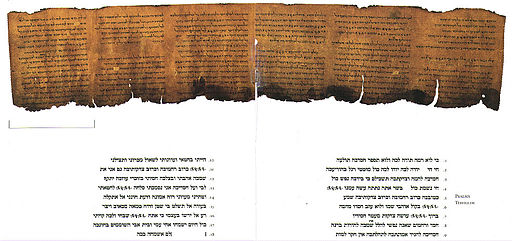

It is probable that these are, more or less, in order of composition. This is thought to be true primarily because the manuscripts that were found at Qumran for section 5 of the psalms show the greatest variation from what is seen later, in 1st or 2nd century CE manuscripts, which suggests that they continued to be fluid or variable in content for some time before being finally fixed as canon later–likely during the second century CE.

Scholars also divide the psalms into different types of prayers--and the divisions can range from 2 to 10 types in how they are described! In general, however, there are hymns of praise and thanksgiving, psalms of lament, psalms praising wisdom, those used for a pilgrimage, and the royal psalms. One could apply more than one description to many of the psalms, of course, as the pilgrimage psalms might be full of praise, or the laments include a connection to royalty. Some of the psalms are oriented toward community worship. Some of them are oriented more to individual worship. Israelites in the temple generally prayed to God as a member of a larger community bound by a covenant and not often as a lone individual.

Almost all of the psalms in Book One are prefaced with the phrase “of (or to) David”. The particle (choosing to use Of or To in those phrases) in Hebrew can be ambiguous, but it is most probably “of David.” Book Two of the Psalms concludes with this postscript: “The prayers of David, the Son of Jesse, are ended.” So at one time the Davidic Psalms were thought to end there, with Psalm 72.

Tradition, however, attributes the entire book of Psalms to King David, and that attribution stems from the fact that 73 of the 150 Psalms are specifically described as being psalms of David. David is said to be a man of considerable musical talent, according to the stories. The attribution or dedication to the various psalms, however, are in many cases added much later to those prayers. So the psalms can only be said to be “of David” if by that term it is meant that the compositions are the result of royal patronage by various kings of the House of David.

There are a number of sub-groupings of psalms within the collection. Psalm 42-83 all use the term Elohim instead of Yahweh to refer to God, and are thus called the Elohist Psalter. All of the Psalms between 120 and 134 bear the same title: A Song of Ascents. They were songs that were probably sung by pilgrims on their way to Jerusalem, because from any direction going into Jerusalem, one has to go up, and so one “ascends” into Jerusalem. The last 5 psalms are a glorious doxology to the entire collection of psalms.

The Biblical text itself lists other authors for some of the Psalms, so Psalm 72 is ascribed to Solomon, Psalm 90 is ascribed to Moses, and still others are ascribed to Assaf and the Sons of Korah, who was an ancestor of a priestly family. Some of them are clearly post-exilic. Psalm 74 laments the destruction of the first temple. Psalm 137 — “By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat, sat and wept as we thought of Zion” is clearly from the perspective of the exile. So the 150 Psalms is an anthology of religious expressions deriving from many centuries of Israel’s history. Despite the claim of religious tradition that the Psalms were actually created by David, it is evident from internal detail that this is simply not true nor possible.

The psalms have been used over the centuries in many forms, for worship, ritual, ceremony and personal reflection. Musical forms might range from Hebrew chant to Gregorian chant, from choral music by Bach to modern pop music set for a band in a church. And all of these would be appropriate, as the original use was varied, too. All psalms were part of Hebrew worship and still are used in that way today, by both Jews and Christians.

Example: modern popular version of Psalm 137 (in Hebrew and English)

Formal Characteristics in the Book of Psalms

A good deal of form critical work has been done on the book of Psalms, looking at the forms that are used in the construction of psalms. Scholars classify psalms according to their forms or their literary genre. They then attempt to place these literary types or genres within the circumstances under which such a psalm would have been written or performed. Scholars ask, “What was happening at the time that this psalm was written or chosen?” In general, the psalms can be categorized formally and thematically in a number of different ways

First come hymns of praise and thanksgiving — these include creation hymns praising God as the creator of the natural world, psalms of thanksgiving, and psalms of trust. This is the largest category of psalms. Many of them celebrate God’s majesty, wisdom, and power, such as this creation hymn.

Psalm 8:

“O Lord, our Sovereign,

how majestic is your name in all the earth!

You have set your glory above the heavens.2 Out of the mouths of babes and infants

you have founded a bulwark because of your foes, to silence the enemy and the avenger.3 When I look at your heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon and the stars that you have established;

4 what are human beings that you are mindful of them, mortals that you care for them?5 Yet you have made them a little lower than God, and crowned them with glory and honor.

6 You have given them dominion over the works of your hands;

you have put all things under their feet,

7 all sheep and oxen,

and also the beasts of the field,

8 the birds of the air, and the fish of the sea,

whatever passes along the paths of the seas.9 O Lord, our Sovereign,

how majestic is your name in all the earth!” (NRSV)

Form for a song of thanksgiving:

- First is an opening invocation to worship, calling others to worship or praise God.

- Then comes a motive clause, which is giving the reason for the praise.

- Finally follows a recapitulation or a renewed call to praise.

So all of Psalm 8 follows this form:

- Verse 1 says “O Lord, our Sovereign, how majestic is your name in all the earth! You have set your glory above the heavens. –There is the invocation.

- Verses 2-8 set out the motives for praise–the glories of creation.

- Verse 9 then reiterates the invocation as a closing to the psalm–“O Lord, our Sovereign, how majestic is your name in all the earth!”

Still other Psalms extol God in the role of Creator; Psalm 104 is one of those. There are also praise psalms that show God as law giver, point out God’s role in history, and rejoice in the protection and opportunities God gave the people.

Example: Psalm 104 in ancient Hebrew with strings

The best known Psalm of trust is the 23rd Psalm. This is a Psalm that employs the metaphor of a shepherd to describe God guiding the individual in straight paths through a time or place of fear. The speaker’s trust creates a sense of hope even in the presence of enemies.

Psalm 23:

“The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want.

2 He makes me lie down in green pastures;

he leads me beside still waters;

3 he restores my soul.

He leads me in right paths

for his name’s sake.4 Even though I walk through the darkest valley,

I fear no evil;

for you are with me;

your rod and your staff—

they comfort me.5 You prepare a table before me

in the presence of my enemies;

you anoint my head with oil;

my cup overflows.

6 Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me

all the days of my life,

and I shall dwell in the house of the Lord

my whole life long.” (NRSV)

Example: Psalm 23

The short Psalm 131 is another psalm of trust that invokes the image of a mother and a child to express an even greater tranquility.

Psalm 131:

“O Lord, my heart is not lifted up,

my eyes are not raised too high;

I do not occupy myself with things

too great and too marvelous for me.

2 But I have calmed and quieted my soul,

like a weaned child with its mother;

my soul is like the weaned child that is with me.3 O Israel, hope in the Lord

from this time on and forevermore.” (NRSV)

These and similar psalms contain some of the most personal depictions of faith, of confidence or simple trust in God.

The second category are psalms of divine kingship or Royal Psalms. These are not quite the same; they are actually two distinct things. Enthronement or kingship psalms celebrate Yahweh as the enthroned ruler, the sovereign ruler of the heavens and as sovereign over foreign nations — so sovereign over nature, sovereign over the human world. And their descriptions of God employ the language and themes that are associated with deities of Ancient Near Eastern mythology, particularly the language associated with Baal, the Canaanite storm god. Some even allude to the defeat of a sea monster as key to God’s role as creator and enthroned king.

Many of the Divine royal psalms begin with the phrase, “The Lord is King”.

So in Psalm 93:

“The Lord is king, he is robed in majesty;

the Lord is robed, he is girded with strength.

He has established the world; it shall never be moved;

2 your throne is established from of old;

you are from everlasting.3 The floods have lifted up, O Lord,

the floods have lifted up their voice;

the floods lift up their roaring.

4 More majestic than the thunders of mighty waters,

more majestic than the waves of the sea,

majestic on high is the Lord!5 Your decrees are very sure;

holiness befits your house,

O Lord, forevermore.” (NRSV)

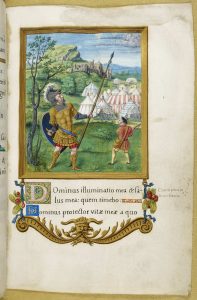

Other Royal Psalms are psalms that praise God’s anointed human King. Some scholars believe that these were coronation psalms. These would have been used at the time of the coronation of a Davidic King, for example.

So Psalm 110 starts out by saying, “The Lord (Yahweh) said to my lord,”– my lord (small l) now meaning the king:

“The Lord says to my lord,

“Sit at my right hand

until I make your enemies your footstool.”2 The Lord sends out from Zion

your mighty scepter.

Rule in the midst of your foes.

3 Your people will offer themselves willingly

on the day you lead your forces

on the holy mountains.

From the womb of the morning,

like dew, your youth will come to you.

4 The Lord has sworn and will not change his mind,

“You are a priest forever according to the order of Melchizedek.5 The Lord is at your right hand;

he will shatter kings on the day of his wrath.

6 He will execute judgment among the nations,

filling them with corpses;

he will shatter heads

over the wide earth.

7 He will drink from the stream by the path;

therefore he will lift up his head.” (NRSV)

But not all of the royal psalms were concerned primarily with military success or guaranteeing military success. Some seek to ensure that the anointed king is bestowed with other qualities necessary for good stewardship.

So we find in Psalm 72: 1-7

“1 Give the king your justice, O God,

and your righteousness to a king’s son.

2 May he judge your people with righteousness,

and your poor with justice.

3 May the mountains yield prosperity for the people,

and the hills, in righteousness.

4 May he defend the cause of the poor of the people,

give deliverance to the needy,

and crush the oppressor.5 May he live while the sun endures,

and as long as the moon, throughout all generations.

6 May he be like rain that falls on the mown grass,

like showers that water the earth.

7 In his days may righteousness flourish

and peace abound, until the moon is no more.” (NRSV)

A third category of psalms are psalms of lament or petition, and these can be a communal supplication, or from the individual. Although individual laments may open with an invocation to or praise of God, some launch immediately into a desperate plea for deliverance from some suffering or crisis. Or they might be a plea for vengeance on one’s enemies. After presenting a complaint, the psalmist will usually confess true trust in God, then ask for help or forgiveness, and conclude with a vow that God will be praised once again.

Psalm 13 has many of these lament features:

“1 How long, O Lord? Will you forget me forever?

How long will you hide your face from me?

2 How long must I bear pain in my soul,

and have sorrow in my heart all day long?

How long shall my enemy be exalted over me?3 Consider and answer me, O Lord my God!

Give light to my eyes, or I will sleep the sleep of death,

4 and my enemy will say, “I have prevailed”;

my foes will rejoice because I am shaken.5 But I trusted in your steadfast love;

my heart shall rejoice in your salvation.

6 I will sing to the Lord,

because he has dealt bountifully with me.” (NRSV)

Psalm 55:12-17 asks for deliverance from the treachery of a deceitful friend:

“It is not enemies who taunt me—

I could bear that;

it is not adversaries who deal insolently with me—

I could hide from them.

13 But it is you, my equal,

my companion, my familiar friend,

14 with whom I kept pleasant company;

we walked in the house of God with the throng.

15 Let death come upon them;

let them go down alive to Sheol;

for evil is in their homes and in their hearts.

16 But I call upon God,

and the Lord will save me.

17 Evening and morning and at noon

I utter my complaint and moan,

and he will hear my voice.” (NRSV)

Some laments are pleas for forgiveness of personal sins. This one is attributed in the psalm itself. In the superscription to the psalm it is attributed to David after the prophet Nathan rebukes him for his illicit relationship with Bathsheba.

Psalm 51:

1 Have mercy on me, O God,

according to your steadfast love;

according to your abundant mercy

blot out my transgressions.

2 Wash me thoroughly from my iniquity,

and cleanse me from my sin.

3 For I know my transgressions,

and my sin is ever before me.

4 Against you, you alone, have I sinned,

and done what is evil in your sight,

so that you are justified in your sentence

and blameless when you pass judgment.

5 Indeed, I was born guilty,

a sinner when my mother conceived me.

6 You desire truth in the inward being;

therefore teach me wisdom in my secret heart.

7 Purge me with hyssop, and I shall be clean;

wash me, and I shall be whiter than snow.

8 Let me hear joy and gladness;

let the bones that you have crushed rejoice.

9 Hide your face from my sins,

and blot out all my iniquities.

10 Create in me a clean heart, O God,

and put a new and right spirit within me.

11 Do not cast me away from your presence,

and do not take your holy spirit from me.

12 Restore to me the joy of your salvation,

and sustain in me a willing spirit.

13 Then I will teach transgressors your ways,

and sinners will return to you.

14 Deliver me from bloodshed, O God,

O God of my salvation,

and my tongue will sing aloud of your deliverance.

15 O Lord, open my lips,

and my mouth will declare your praise.

16 For you have no delight in sacrifice;

if I were to give a burnt offering, you would not be pleased.

17 The sacrifice acceptable to God is a broken spirit;

a broken and contrite heart, O God, you will not despise.

18 Do good to Zion in your good pleasure;

rebuild the walls of Jerusalem,

19 then you will delight in right sacrifices,

in burnt offerings and whole burnt offerings;

then bulls will be offered on your altar.” (NRSV)

Example: Psalm 51 JS Bach

The communal laments bewail Israel’s misfortunes and urge God’s vengeance upon Israel’s oppressors, sometimes even reminding God of the historic relationship with Israel and the covenantal obligations between them.

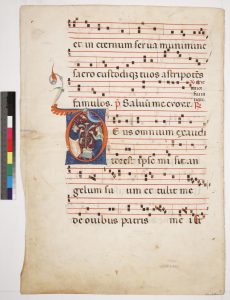

Psalm 74 is a case in point, making reference to the destruction of the sanctuary. It was clearly written in a post-exilic period. And as a response to the catastrophe, it gives expression to despair and bewilderment and even anger that God has forgotten any obligations to Israel.

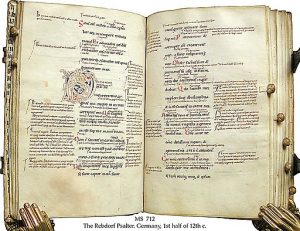

Initial D with God blessing David.

Psalm 74:1-11, 20-23

“1 O God, why do you cast us off forever?

Why does your anger smoke against the sheep of your pasture?

2 Remember your congregation, which you acquired long ago,

which you redeemed to be the tribe of your heritage.

Remember Mount Zion, where you came to dwell.

3 Direct your steps to the perpetual ruins;

the enemy has destroyed everything in the sanctuary.4 Your foes have roared within your holy place;

they set up their emblems there.

5 At the upper entrance they hacked

the wooden trellis with axes.

6 And then, with hatchets and hammers,

they smashed all its carved work.

7 They set your sanctuary on fire;

they desecrated the dwelling place of your name,

bringing it to the ground.

8 They said to themselves, “We will utterly subdue them”;

they burned all the meeting places of God in the land.9 We do not see our emblems;

there is no longer any prophet,

and there is no one among us who knows how long.

10 How long, O God, is the foe to scoff?

Is the enemy to revile your name forever?

11 Why do you hold back your hand;

why do you keep your hand in your bosom?…

20 Have regard for your covenant,

for the dark places of the land are full of the haunts of violence.

21 Do not let the downtrodden be put to shame;

let the poor and needy praise your name.

22 Rise up, O God, plead your cause;

remember how the impious scoff at you all day long.

23 Do not forget the clamor of your foes,

the uproar of your adversaries that goes up continually.” (NRSV)

The psalmist is bewildered: why has this happened, why doesn’t God act? There’s no mention of Israel’s sin; there’s no indication that the destruction was just punishment. Some psalms even claim that God is the one at fault, that the people have been faithful, but God has forgotten about them, or not remember how important the various covenants are.

Some parts of Psalm 44 show this approach:

![1185-1199 Place Bodensee, Germany Notes Initial B with David as a Musician This initial begins Psalm 1, 'Beatus vir' (Blessed [is] the man). The rest of the psalm continues on the reverse of the leaf. The B of the first psalm was a common place to find decoration, often with an image of King David playing music, as in this example, because David was believed to have composed the psalms. Thus the images of the king at the beginning of the book functioned as an author portrait.](https://minnstate.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/7/2021/10/psalm-44-279x300.jpg)

Initial B with David as a Musician

This initial begins Psalm 1, ‘Beatus vir’ (Blessed is the man). The B of the first psalm was a common place to find decoration, often with an image of King David playing music, as in this example, because David was believed to have composed the psalms. Thus the images of the king at the beginning of the book functioned as an author portrait.

Psalm 44: 6-14, 17, 23-24

6 For not in my bow do I trust,

nor can my sword save me.

7 But you have saved us from our foes,

and have put to confusion those who hate us.

8 In God we have boasted continually,

and we will give thanks to your name forever.9 Yet you have rejected us and abased us,

and have not gone out with our armies.

10 You made us turn back from the foe,

and our enemies have gotten spoil.

11 You have made us like sheep for slaughter,

and have scattered us among the nations.

12 You have sold your people for a trifle,

demanding no high price for them.13 You have made us the taunt of our neighbors,

the derision and scorn of those around us.

14 You have made us a byword among the nations,

a laughingstock among the peoples….17 All this has come upon us,

yet we have not forgotten you,

or been false to your covenant…23 Rouse yourself! Why do you sleep, O Lord?

Awake, do not cast us off forever!

24 Why do you hide your face?

Why do you forget our affliction and oppression?” (NRSV)

This psalm contains a denial of the charges against Israel found in many of the prophetic books. The psalm speaks for the nation, saying, “We have not forgotten you, we haven’t been false to your covenant, our hearts haven’t gone astray, we haven’t swerved from your path. Why are you behaving this way?” This view is asserting God’s negligence rather than Israel’s guilt.

Example: Psalm 22, which begins with “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Eli, Eli, lama asavtani in Hebrew) has always been the cry of the Jew under duress. This traditional chant (sung by Magdalith) has been put with faces from the Holocaust to remind us that this is a lament that is timeless. Made for The Well, a Christian community in Brussels, Belgium for their Lent theme of LAMENT.

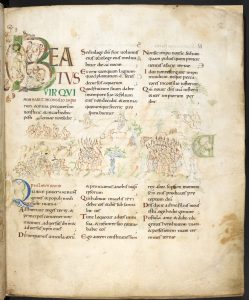

There is a category of psalms that have a more reflective or meditative tone. These are psalms of wisdom, psalms in praise of instruction or of the Torah and meditation. Many of them begin with the phrase, “Happy is the one who…”

Psalm 128:

“Happy is everyone who fears the Lord,

who walks in his ways.

2 You shall eat the fruit of the labor of your hands;

you shall be happy, and it shall go well with you.3 Your wife will be like a fruitful vine

within your house;

your children will be like olive shoots

around your table.

4 Thus shall the man be blessed

who fears the Lord.5 The Lord bless you from Zion.

May you see the prosperity of Jerusalem

all the days of your life.

6 May you see your children’s children.

Peace be upon Israel!” (NRSV)

Example: Psalm 128

Many psalms seem to assume worship happening in the temple, and can even have a call and response, or call and echo character. But there are three that, instead, have this theme of meditating upon or delighting in the Torah; that’s Psalm 1, Psalm 19, and Psalm 119.

119 is the longest psalm because it’s written in acrostic form. There are different stanzas, a different stanza for each letter of the alphabet (22 letters) and there are eight lines in each stanza, all eight lines beginning with that letter of the alphabet, so it’s a very long psalm.

Psalm 19 represents the studying Torah as an activity that makes one wise and happy.

Psalm 19:8-10

“8 the precepts of the Lord are right,

rejoicing the heart;

the commandment of the Lord is clear,

enlightening the eyes;

9 the fear of the Lord is pure,

enduring forever;

the ordinances of the Lord are true

and righteous altogether.

10 More to be desired are they than gold,

even much fine gold;

sweeter also than honey,

and drippings of the honeycomb.” (NRSV)

This elevation of Torah reflects the shift that begins in the late Second Temple Period, in which study of the Torah is of growing importance, perhaps the 2nd or 1st century BCE.

Then, finally, there are the pilgrimage psalms, found in Psalms 120-134. Many of these are familiar, and certainly fall into the category of praise and thanksgiving psalms, too. An example would be Psalm 122:

1 I was glad when they said to me,

“Let us go to the house of the Lord!”

2 Our feet are standing

within your gates, O Jerusalem.

3 Jerusalem—built as a city

that is bound firmly together.

4 To it the tribes go up,

the tribes of the Lord,

as was decreed for Israel,

to give thanks to the name of the Lord.

5 For there the thrones for judgment were set up,

the thrones of the house of David.

6 Pray for the peace of Jerusalem:

“May they prosper who love you.

7 Peace be within your walls,

and security within your towers.”

8 For the sake of my relatives and friends

I will say, “Peace be within you.”

9 For the sake of the house of the Lord our God,

I will seek your good.” (NRSV)

Example: Richard Woodward: Psalm 122 (Anglican chant) (King’s College Choir

So it is obvious that there are many different ways to categorize and classify the psalms. These general categories blur and mix within the canon, so recognizing the general patterns and categories helps the reader have some feel for what is important about the particular psalm in question. Many psalms seem to contain portions of their wording that would normally fall into different categories.

It should be clear that the Psalms reflect the religious insights of Israelites in many different moods, and for many kinds of occasions. Perhaps that diversity of experience and feeling is the reason that the Psalms have become a great source for personal spirituality in Western civilization.

Some of the psalms were composed as many as 3000 years ago and yet can feel relevant to contemporary readers. They can provide an opportunity to confess one’s failings or to proclaim good intentions, or to rail against misfortune, or to cry out against injustice, or to request assistance, or to affirm trust in divine providence, or to simply express emotions of praise and joy, and wonder at creation, or reflect on human finitude in the face of divine infinitude.

Characteristics of the Psalms’ poetry

Some scholars call poetry “heightened discourse” in order to differentiate between poetry and prose. Psalms have certainly been considered poems instead of prose. Psalms have a whole variety of poetic characteristics that become more evident as one begins to read through them.

Scholars have analyzed and parsed and dissected these poems, but some general ideas to note about how these are written are these:

- Many of the psalms use something called parallelism. Articles about this within the Oxford Annotated NRSV say, “The main characteristic of Biblical poetry is parallelism, in which most poetic lines may be divided into two; the second part of the line is intimately connected to the first.” (examples to follow)

- The psalms have many metaphors, which is also called figuration. Many rich and interesting images are used to refer to God, including those fairly familiar to many people–shepherd, king, rock–as well as others not quite as well known, such as fortress, mother, or winged creature. The psalm might start with an image, and then use the rest of the song to unpack that image in describing the divine.

- In the psalms there is no real use of rhyme. Even in the original Hebrew, lines are not set up to use any kind of rhythm or rhyme commonly found in some English poetry.

Various example of the above characteristics are easy to see in the Psalms. Parallelism can be shown almost anywhere–such as seen in Psalm 146:2

I will praise the Lord as long as I live;

I will sing praises to my God all my life long.

The first line says that the person will praise the Lord, the second line agrees, saying the same thing again in a slightly different way. This is seen over and over in within the Psalms, and it is the most common characteristic of the psalms, found in all the different categories of psalms.

Sometimes the parallelism is supportive of the original statement, seen in the first example here. But sometimes it is, instead, something that differs from the first line. And sometimes the second part of a verse or sentence is a phrase that just intensifies the first. There are slightly different approaches to this parallelism in Psalm 121.

Psalm 121:

I lift up my eyes to the hills—

from where will my help come?

2 My help comes from the Lord,

who made heaven and earth.

In this first verse, we have a question and an answer.

3 He will not let your foot be moved;

he who keeps you will not slumber.

4 He who keeps Israel

will neither slumber nor sleep.

In verse 3 we have a supportive style parallel from the first phrase, and in verse 4 it is intensified even more, as if repetition can reassure the reader.

5 The Lord is your keeper;

the Lord is your shade at your right hand.

6 The sun shall not strike you by day,

nor the moon by night.

In verse 5 the Lord as keeper is a general idea, but the Lord as shade–this is now about protection, right? And then we add that this protection will make sure that neither sun or moon can hurt anyone because of God’s protection. This intensifies the idea.

7 The Lord will keep you from all evil;

he will keep your life.

8 The Lord will keep

your going out and your coming in

from this time on and forevermore.” (NRSV)

And the last 2 verses are a glorious summary of how God will protect the people, not letting any evil touch them, and even protecting one’s birth and death. It is a very clear use of parallelism all through the prayer, and very standard formatting for the psalms in general.

There can also be psalms where something is said that is antithetical to the first statement–such as found in Psalm 34:10

“The young lions suffer want and hunger,

but those that seek the Lord lack no good thing”

or in Psalm 1:6

“For Yahweh takes care of the way the virtuous go,

but the way of the wicked is doomed.”

Psalms likely were a kind of libretto, or set of verses, that could be set to music for temple worship. Indications of how these were to be performed are attached to some psalms, and with others, the directions of how they were to be performed are a little unclear. Over the centuries, both from Jewish origins and later from Christian, the use of the psalms has been extensive.

There are many possible exquisite samples of psalm settings to share. One 20th century extensively performed example is the Chichester Psalms composed by Leonard Bernstein who, for those who are not musical students, is the composer of the West Side Story music. In it Bernstein uses Psalms 108, 100, 23, 2, 131, and 133.

Example: Chichester Psalms by Leonard Bernstein, Le Choeur et la Maîtrise de Radio France

May, Herbert G., et al. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha: Revised Standard Version, Containing the Second Edition of the New Testament and an Expanded Edition of the Apocrypha. Edited by Michael D Coogan, Oxford University Press, 2007.

Gabel, John B. The Bible as Literature: An Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2006.

a liturgical formula of praise to God.