4 Primeval and Ancestral: historical context of the Israelite people

Primeval History: Genesis 1-11

Ancestral History: the rest of Genesis

Human civilization (as opposed to human existence, which is something else altogether) is very, very old. Nevertheless, knowledge of the earliest stages of human civilization was quite limited until the archaeological discoveries of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, which unearthed the great civilizations of the Ancient Near East. These great civilizations include ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the area referred to as the Fertile Crescent, of which a little part (about the size of Rhode Island) is called Canaan. The map shows that this covers modern day Egypt, Israel, Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Iraq, some of Turkey, and into Iran. This was land that became part of the regional movement for the development of agriculture.

Archaeologists in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were stunned to find, as they explored and dug in this region, the ruins and the records of many remarkable peoples and cultures — massive, complex empires in some cases, some of which had completely disappeared from human memory.

And so many scholars, and many people, have remarked that it’s not a small irony that the Ancient Near Eastern people with one of the most lasting legacies was not a people that built and inhabited one of the great centers of Ancient Near Eastern civilization. It can be argued that the Ancient Near Eastern people with the most lasting legacy is a people that mostly just had an idea, and not much else! It was a new idea those people had, however, one that broke with the ideas of its neighbors, and those people with the new idea were the Israelites.

Scholars have come to the realization that despite the Bible’s pretensions to the contrary, the Israelites were a small and insignificant group for much of their history. They did manage to establish a kingdom in the land that was known in antiquity as Canaan around the year 1000 BCE. They probably succeeded in subduing some of their neighbors, even collecting tribute, but in about 922 BCE this kingdom divided into two smaller and lesser kingdoms that fell in importance. The northern kingdom, which consisted of ten of the twelve Israelite tribes, and was known confusingly as Israel, was destroyed in 722 BCE by the Assyrians. The southern kingdom, which consisted of two of the twelve tribes and was known as Judah, managed to survive until the year 586 BCE when the Babylonians came in and conquered Judah and sent the people who lived there (well, the wealthier and better educated among them, at least) into exile. The capital, Jerusalem, fell in a siege that year.

Conquest and exile were events that normally would spell the end of a particular ethnic national group, particularly in antiquity. Conquered peoples would trade their defeated god for the victorious god of their conquerors and eventually there would be a cultural and religious assimilation and intermarriage. That conquered people would disappear as a distinctive entity, and in effect, that is what happened to the ten tribes of the northern kingdom to a large degree. They were lost to history as they left the area after the war of Assyrian conquest, intermarried, and were assimilated.

This did not happen to those members of the nation of Israel who lived in the southern kingdom, Judah. Despite the demise of their national political base in 586 BCE, the Israelites alone among the many peoples who have figured in Ancient Near Eastern history — the Sumerians, the Akkadians, the Babylonians, the Hittites, the Phoenicians, the Hurrians, the Canaanites — emerged after the death of their state, producing a community and a culture that can be traced through various twists and turns and vicissitudes of history right down into the modern period. And they carried with them the idea and the traditions that laid the foundation for the major religions of the western world: Judaism, Christianity and Islam.

The conception of the universe that was widespread among ancient peoples is that those people regarded the various natural forces as imbued with divine power. The earth was a divinity, the sky was a divinity, the water was a divinity, these all had divine power. In other words, the gods were identical with, or imminent in, the forces of nature. There were many gods found in nature. No one single god was therefore all powerful.

There is very good evidence to suggest that ancient Israelites by and large shared this world view at first. They participated at the very earliest stages of their existence in the wider religious and cultic culture of the Ancient Near East. However, over the course of time, some ancient Israelites, not all at once and not unanimously, broke with this view and articulated a different view, that there was one divine power, one god.

Key Point: God is not Nature

But much more important than the number of gods was the fact that this one single god was outside of and above nature. This god was not identified with nature. This god transcended nature, and wasn’t known through nature or natural phenomena. This god was known through history, events and a particular relationship with humankind.

That idea affected every aspect of Israelite culture and it was an idea that ensured the survival of the ancient Israelites as an entity, as an ethnic religious entity. In various complicated ways, the view of an utterly transcendent god with absolute control over history made it possible for some Israelites to interpret even the most tragic and catastrophic events, such as the destruction of their capital and the exile of their remaining peoples, not as a defeat of Israel’s god or even God’s rejection of them, but as a necessary part of God’s larger purpose or plan for Israel.

An important goal here is to introduce a number of approaches to the study of the Bible, different methodological approaches that have been advanced by modern scholars but some of which are in fact quite old.

At times we will be literary critics.

“How does this work as literature? What kind of writing is this, anyhow?”

At times we will be religious and cultural critics.

“What is it that the Israelites were saying in their day, in their time, and for whom was this written, and for what reason?”

At times we will be historians.

“What was going on in this region during the time this was written? Did that impact Israel? How? “

One goal of this text is to explain the culture of ancient Israel as represented in the Bible against the backdrop of its Ancient Near Eastern setting, and its historical and cultural setting. One of the major consequences of archaeological finds from this era is the light that they have shed on the background and the origin of the materials in the Bible. The traditions in the Bible did not come out of a vacuum, but can be placed in the context of a much broader mix of cultures, history, literature and philosophies.

An interesting source: Biblical Archaeology Society

You might find many and varied materials interesting at the Biblical Archaeological Review or the Biblical Archeology Society

The early chapters of Genesis, Genesis 1 through 11 are known as the “Primeval History.”

“Primeval History” is an unfortunate name for this material from the beginning of Genesis, because these chapters really are not best read or understood as history at all, at least not in the conventional sense. These eleven chapters owe a great deal instead to Ancient Near Eastern mythology. The creation story in Genesis 1 draws upon the Babylonian epic known as Enuma Elish. The story of the first human pair in the Garden of Eden, which is in Genesis 2 and 3, has clear affinities with the Epic of Gilgamesh, which is a Babylonian epic in which a hero embarks on an exhausting search for immortality.

It might be interesting to check out a little tongue in cheek history:

The story of Noah and the flood, which occurs in Genesis 6 through 9 is simply an Israelite version of an older flood story –a Mesopotamian story called the Epic of Atrahasis– and a flood story also incorporated in the Epic of Gilgamesh. Biblical traditions have roots that stretch deep into earlier times and out into surrounding lands and traditions, and the parallels between the Biblical stories and various other Ancient Near Eastern stories has been the subject of intense study.

Example: Noah and Ziusudra

It isn’t just the similarity between the Biblical materials and the Ancient Near Eastern sources that is important to us. In fact, in some ways it’s the dissimilarity that is remarkably important to us, the Biblical transformation of a common Near Eastern heritage in light of its radically new conceptions of God and the world and humankind.

We have a Sumerian story from about 3000 BCE. It’s the story of Ziusudra, and it’s very similar to the Genesis flood story of Noah. In both of these stories, the Sumerian and the Israelite story, you have a flood that is the result of a deliberate divine decision; one individual is chosen to be rescued; that individual is given very specific instructions on building a boat; he is given instructions about who to bring on board; the flood comes and exterminates all living things; the boat comes to rest on a mountaintop; the hero sends out birds to reconnoiter the land; when he comes out of the ark he offers a sacrifice to the god — the same narrative elements are in these two stories. It’s just wonderful when you read them side by side.

What is of great significance is not simply that the Biblical writer is retelling a story that clearly went around everywhere in ancient Mesopotamia; they were transforming the story so that it became a vehicle for the expression of their own values and their own views. In the Mesopotamian stories, for example, the gods act capriciously, the gods act on a whim. In fact, in one of the stories, the gods say, “Oh, people, they’re so noisy, I can’t sleep, let’s wipe them all out.” That’s the rationale. There’s no moral scruple. They destroy these helpless but stoic humans who are chafing under their tyrannical and unjust and uncaring rule.

In the Biblical story, when the Israelites told the story, they modified it. It’s God’s uncompromising ethical standards that lead him to bring the flood in an act of divine justice. God’s punishing the evil corruption of human beings that God has so lovingly created and whose degradation God can’t bear to witness. So it’s saying something different. It’s providing a very different message.

So when the Bible is compared with other literature of the Ancient Near East, one sees not only the incredible cultural and literary heritage that was obviously common to them, but also the ideological gulf that separated them. Biblical writers beautifully and cleverly manipulated and used these stories as a vehicle for the expression of a radically new idea. They drew upon these sources, but they also blended and shaped them in a new and particular way.

And so a critical problem arises facing anyone who seeks to reconstruct ancient Israelite religion or culture on the basis of the Biblical materials. Those who were responsible for the final editing, for the final forms of the Biblical texts, had a decidedly monotheistic perspective, an ethical monotheistic perspective. These editors and rabbis and scholars attempted to impose that perspective on their older source materials and for the most part they were successful. But at times the result of their effort is a deeply conflicted, deeply ambiguous text. It is hard to get away from the ancient stories completely, and the Bible doesn’t always manage it.

In many respects, the Bible represents or expresses a basic discontent with the larger cultural milieu in which it was produced. One can read the Bible with fresh and appreciative eyes only if first acknowledging and setting aside some presuppositions about the Bible.

It’s really impossible not to have some opinions about the Bible and its content, because it is an intimate part of modern culture. So even if a person has never opened it or read it, it is likely that they can cite a line or two without perhaps even knowing that these are Biblical — “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth,” “love your neighbor as yourself” “wolf in sheep’s clothing” and yet not knowing what any of those sayings mean. These are things and phrases that people hear and when they find out that these are in the Bible, it creates a certain impression of the Biblical text and how it functions.

Verses from the Bible are often quoted or alluded to, whether to be held up with admiration or whether to be tossed away as irrelevant. But is it easy to feel that any person could have a rough idea of the Bible and a rough idea of its outlook when in fact what they really have are popular misconceptions that come from the way in which the Bible has been used or misused. People can attribute meaning and intent to the Bible that simply is not there.

Important Quote:

“Most of our cherished presuppositions about the Bible are based on astonishing claims that others have made on behalf of the Bible, claims that the Bible has not made on behalf of itself.”

The rest of the book of Genesis, from chapter 12 to the end, is called Ancestral History.

The term Ancestral History is also not particularly helpful terminology to describe the rest of Genesis starting with chapter 12. But it does refer to the idea that from the stories of Abraham and Sarah, and all the following descendants of these two, comes the foundational story of monotheism, establishing the roots of the Abrahamic faiths, and explaining the ways that Yahweh established a covenant with these specific ancient Near Eastern people. Creative Commons licensed comments from Dr. Anna Sapir Abulafia[2] embedded in this next section can help understand the Jewish approach to Abraham:

In Genesis 12: 1–3 Abraham (at that stage his name is still Abram) is called by God to: ‘Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you. I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you, and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing … and in you all the families of the earth shall be blessed’ (NRSV).

Because Abraham’s wife Sarai (later Sarah) remains childless, Abraham has a son with Sarah’s slave Hagar. The child is called Ishmael. At this stage (Genesis 17) Abraham receives the commandment to start the circumcision of all males when they are eight days old as a symbol of the covenant between the Hebrew people and God. At the same time Abraham is told that Sarah will bear a son as well. This son of the marriage is named Isaac.

Trouble brews between Sarah and Hagar as their sons grow up, and Sarah persuades Abraham to send Hagar and Ishmael away (Genesis 21). God promises Hagar that Ishmael too will be made into a great nation, just as God has promised this to Abraham about the heritage for Isaac. God then tests Abraham’s faith by commanding him to sacrifice Isaac (Genesis 22). But when Abraham is about to sacrifice Isaac on Mount Moriah, an angel stops him and directs his gaze to a ram caught in the thicket. The ram is to be sacrificed instead of Isaac. Throughout Genesis, Abraham is depicted as a man who fully trusts God and who follows God’s commandments.

In Jewish tradition Abraham became identified as the ‘first Jew’. He is depicted as the embodiment of the faithful Jew upholding God’s commandments. Traditionally, Jews see themselves as the descendants of Abraham through his son Isaac and through Jacob, his grandson. In Jewish prayer-books God is referred to as the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, and Jews are called the bnei Ya’akov/Israel, (‘the children of Jacob/Israel’). The name of Jacob was changed to Israel in Genesis 32: 29.

This set of stories, with many more, established the place of Abraham in Judaism, and eventually the place of Abraham in Christianity and in Islam as well.

The lack of any real clues from actual history make the dating of the Genesis ancestral materials very difficult. Identifying when the authors and redactors of the Torah thought this all happened is virtually impossible. A few little hints might show some timing for the stories–the reference to the Hebrew god as El coincides with the mention of El in texts from northwest Syria, El being the head of the Canaanite pantheon of gods. And some of the names used in Genesis sound Egyptian in origin, which could lend some credence to the idea that the Hebrew people ended up in Egypt at some point, for some reason.

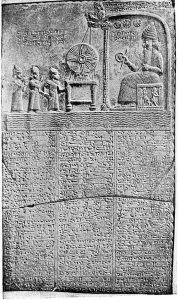

But the process of redaction, editing, re-telling and finally getting all of this written down has taken any real hints of what modern people would call history out of these accounts. There is a small hint that in the time of Merneptah, pharaoh of Egypt from 1213–1203 BCE, there was a country called Israel. This comes from a war memorial called, fittingly enough, the Merneptah Stele, celebrating the defeat of Israel by the Egyptians. The stele dates to about 1209 BCE. It is the first physical indication, in the kind of history that modern scholars accept, that shows the existence of Israel. So the accounts of the ancestral people–the people who followed Abraham–had to happen before that time. Very tentative dates put the times of Genesis 12 and following at around 2000-1275 BCE. The book of Exodus begins a different kind of story.

Hayes, Christine. “Introduction to the Old Testament (Hebrew Bible).” Introduction to the Old Testament (Hebrew Bible) | Open Yale Courses, https://oyc.yale.edu/religious-studies/rlst-145.

Abulafia, Anna Sapir. “The Abrahamic Religions.” British Library, Discovering Sacred Texts, Sept. 2019, https://www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/articles/the-abrahamic-religions.

British Library Sacred Texts: Judaism, Sept. 2019, https://www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/videos/judaism.

Gabel, John B. The Bible as Literature: An Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2006.

“Mesopotamia: Crash Course World History #3 .” Crash Course: World History, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sohXPx_XZ6Y.

- Christine Hayes is the Robert F. and Patricia Ross Weis Professor of Religious Studies at Yale. She received her Ph.D. from University of California, Berkeley in 1993. A specialist in talmudic-midrashic studies, Hayes offers courses on the literature and history of the biblical and talmudic periods. She is the author of two scholarly books: Between the Babylonian and Palestinian Talmuds, recipient of the 1997 Salo Baron prize for a first book in Jewish thought and literature, and Intermarriage and Conversion from the Bible to the Talmud, a 2003 National Jewish Book Award finalist. She has also authored an undergraduate textbook and several journal articles. ↵

- Anna Sapir Abulafia is Professor of the Study of the Abrahamic Religions at the Faculty of Theology and Religion at the University of Oxford and a Fellow of Lady Margaret Hall. She has published widely on medieval Christian-Jewish relations. At present she is engaged in a project examining the place of Jews and Muslims in Gratian’s Decretum ↵