18 John

John

The Gospel of John seems to be from a very different perspective than that of the synoptic Gospels: Matthew, Mark, and Luke. There is less action in the Gospel of John and more talk. It reads much more like philosophy, and less like a series of stories. The style in John is repetitious. There are phrases and words that come up over and over again, especially referring to darkness and light.

There are some scenes in the Gospel of John where the characters do seem more lifelike than they do in the synoptic Gospels, however. In the synoptic Gospels the characters are just a tax collector, a sinner, a Pharisee, a Syrophoenician woman, a Centurion who had a slave. Much of the time they don’t have a name, most of the time they’d say at most one or two things to Jesus. It is very different in the Gospel of John. In the Gospel of John characters often look and act much more lifelike and filled out than they have been in the synoptic Gospels. The reader knows something about them, and the people involved actually have conversations with Jesus. Still, the gospel of John is less of a bios and more of a presentation of the issues to be addressed to his church.

The gospel describes what is called Johannine Christianity, which is one of the scholarly words used to describe the ideas found in John’s gospel. There really were differing forms of Christianity early in the development of the faith, and John’s gospel describes a different set of ideas about Jesus and about the church than the synoptic gospels do. The synoptics have some different approaches from one another, but in general their ideas about Jesus and the stories that they tell coordinate well.

John’s gospel is very different. John’s ideas and approach to faith and to the person of Jesus, which were written down about 15-20 years later than the synoptics, form a type of Christianity that focuses much more on the divinity of Jesus, and not as much on the humanity of Jesus.

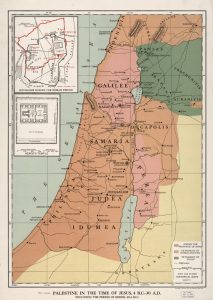

The length of Jesus’ ministry, in the synoptic gospels, probably lasted about a year, not much more than that. There’s just no indication of how long the ministry actually takes but in the synoptics, Jesus goes to Jerusalem only one time for the Passover and that is at the end of his life. In the Gospel of John there are three different mentions of Passovers. There’s the Passover in 2:13, when he goes up to Jerusalem and cleanses the temple there. There’s another Passover mentioned in 6:4, and there’s a third Passover mentioned in 13:1, which is the Passover at the end of Jesus’ life, at the time when he is arrested. Three Passovers occur in Jesus’ ministry, according to the Gospel of John.

Also, in the first three Gospels, Jesus’ entire ministry takes place in Galilee until the last part of his life. He then journeys to Jerusalem, and according to those synoptic Gospels, he is only in Jerusalem for one week and then is crucified. That’s not the way it happens in the Gospel of John. For example, the cleansing of the temple happens at the beginning of the Gospel of John, not at the end like in the other gospels, where that cleansing is a part of the activities of Holy Week. Jesus was in and out of Jerusalem regularly in John’s gospel.

Jesus’ hometown, according to Matthew, is Bethlehem. That’s where the family starts off, and that’s where they end up. In Matthew, Jesus only goes to Galilee later. According to the Gospel of Luke, Jesus’ family is from Nazareth in Galilee. They go to Bethlehem only for the census, and then a month or so after the birth they go back to Galilee. John doesn’t say anything about the birth of Jesus, especially not mentioning Bethlehem. In John people say to Jesus, “How can you be the Messiah? Who says the Messiah is supposed to come from Galilee? The Messiah doesn’t come from Galilee, the Messiah’s supposed to come from Bethlehem.” John allows the reader to understand that the people must have gotten it wrong, if they thought that the Messiah could not come from Galilee. Jesus can be from Galilee, and this is where John places his home.

Prologue to John

Many of the big ideas in John are found summarized in the prologue, found at the beginning of chapter 1:

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. 2 He was in the beginning with God. 3 All things came into being through him, and without him not one thing came into being. What has come into being 4 in him was life, and the life was the light of all people. 5 The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overtake it.

6 There was a man sent from God whose name was John. 7 He came as a witness to testify to the light, so that all might believe through him. 8 He himself was not the light, but he came to testify to the light. 9 The true light, which enlightens everyone, was coming into the world.

10 He was in the world, and the world came into being through him, yet the world did not know him. 11 He came to what was his own, and his own people did not accept him. 12 But to all who received him, who believed in his name, he gave power to become children of God, 13 who were born, not of blood or of the will of the flesh or of the will of man, but of God.

14 And the Word became flesh and lived among us, and we have seen his glory, the glory as of a father’s only son, full of grace and truth. 15 (John testified to him and cried out, “This was he of whom I said, ‘He who comes after me ranks ahead of me because he was before me.’ ”) 16 From his fullness we have all received, grace upon grace. 17 The law indeed was given through Moses; grace and truth came through Jesus Christ. 18 No one has ever seen God. It is the only Son, himself God, who is close to the Father’s heart, who has made him known.”

The prologue contains a number of key ideas that are found throughout the rest of the gospel narrative. If those are laid out a bit, it becomes easier to see the ideas throughout the rest of the gospel.

- The most important idea from the prologue is the statement of Jesus’ pre-existence. In no other Gospel can you find the idea that Jesus existed before his birth. That’s counterintuitive to a lot of readers because Christians are used to thinking about Jesus as an eternal divine being who becomes incarnate as a human being but always existed. That’s not in the other Gospels as a belief, but it’s definitely here in the Gospel of John.

- There is a theme of life; of light and darkness. Jesus comes from light, he comes into darkness, the darkness doesn’t receive him, he brings light and life to his followers. The world is not simply the physical world, it’s the cosmos, all the universe. Jesus comes into the cosmos, which is a dark enemy place. The world is a place of enmity, the world hates Jesus, the world hates the disciples, the world hates followers of Jesus. But the followers will find light and life through Jesus.

- God is Jesus’ father in the Gospel of John. That’s true, a bit, in the other Gospels but it’s seen more clearly and regularly in the Gospel of John.

- John the Baptist is a prophet, but is the lesser of the two men, seen right away in the prologue. John the Baptist is found in verse 6 of the prologue, “There was a man sent from God whose name was John, he came as a witness to testify to the light so that all might believe in him. He himself was not the light.” This writer states from the very beginning that John the Baptist is not Jesus’ equal, he’s a secondary witness, and tells the reader this to avoid any possible confusion.

- An idea is stated that “the law comes from Moses but grace and truth come from Jesus.” This comes up in other places (people have interpreted Matthew in this way, which is part of the problem of Anti-Semitism mentioned in a previous chapter) but it is stated much more clearly in John.

- There is an emphasis on seeing and knowing as ways to understand and believe that Jesus is the messiah, and these ideas are also in the prologue to the Gospel.

The Structure of John

Start thinking about John’s gospel with a little help from this video. There may be some differences from scholar to scholar about a few things–dates range from 90-110 CE for the writing of the gospel, and because of this it was obviously not the actual disciple John who wrote it down. John’s story is part of the gospel narrative, of course, but the disciple John is not the writer. And not all scholars think that the writer of the gospel of John is the same person who wrote Revelation, different from what this scholar says. Still, this video can get you started.

Most scholars identify four specific sections within the Gospel of John:

- a prologue (1:1–18) identifying Jesus as divine, sent to all who would believe in him

- an account of the ministry, often called the Book of Signs (1:19–12:50) which contains the 7 miracles showing who Jesus is, and also containing the 7 “I am” sayings

- the account of Jesus’ final night with his disciples, the passion, and the resurrection which is sometimes called the Book of Glory (13:1–20:31)

- and a conclusion (20:30–31) which expresses the intent of the gospel–to promote belief

Sometimes an epilogue is added to John, in the form of a chapter 21, but the majority of scholars believe that this is a later addition, added to talk about the fate of Peter and the Beloved Disciple.

Example: talking about elements found in John’s gospel

Major Themes of the Gospel of John

One of the key ideas in John is the descending and ascending redeemer figure. This is the concept of Jesus as divine–pre-existing, as God. Jesus is the one who came down from above, and he is the one who is going back up.

Look at John 1:51

“And he said to him, very truly I tell you, you will see heaven open and the angels of God ascending and descending upon the Son of Man,”

Look at 3:13

“No one has ascended into heaven except the one who descended from heaven, the Son of Man.”

Look at 3:31,

“The one who comes from above is above all, the one who is of the earth belongs to the earth and speaks about earthly things. The one who comes from heaven is above all.”

The words “coming from above” occur over and over in the Gospel of John. Where Jesus came from and where Jesus is going gets confusing. Jesus preaches to people that they cannot go where he is going. Is he going to go out to the Greeks and preach to the Greeks? Is he going to go back to Galilee? What does he mean, he’s “going”? People are always misunderstanding this. There are places where it seems clear that he is going back to heaven. In other places, the meaning is a bit obscure.

Very similar to that idea of coming from above is the theme of being lifted up. What does this mean when Jesus talks about the Son of Man being lifted up? Does it mean his ascension into heaven? Does it mean his resurrection from the dead? John’s gospel offers little explanation of exactly what is meant with this concept, so that being “lifted up” is one of the themes that seems to accompany the ascending and descending idea found all through John. And these themes get a little complicated. At one point Jesus says, “Everyone who comes to me when I am lifted up I will lift up.” Jesus seems to be saying that he will lift up people who are his disciples. This going up and coming down is found all the way through the Gospel.

The concepts of Knowing and Seeing are vital themes in John.

1:18: “No one has ever seen God. It is God the only Son who is close to the Father’s heart who has made him known.”

It’s not always clear to the reader whether one knows by seeing, or whether seeing leads to a form of knowing? These are big problems that the Gospel of John poses and that scholars argue about.

Look at 1:34,

“And I myself have seen and have testified that this is the Son of God.”

Look at 1:39,

“He came to them, ‘Come and see.’

There are many, many verses in John containing the verb “to see”, and most of them refer to faith or belief. Again, it’s always a little bit difficult in the Gospel of John to figure out whether a person has to see something in order to have faith. At the resurrection, Jesus appears to Mary Magdalene, and talks with her. He sends her off to tell the disciples about the resurrection. When she finds them, the verb again is “to see”– in John 20:18,

18 Mary Magdalene went and announced to the disciples, “I have seen the Lord,” and she told them that he had said these things to her.

The most famous story about seeing concerns the disciple Thomas, who personally has not seen Jesus alive again after the resurrection, and who claims that he must see and touch Jesus in order to believe that he is actually alive. And sure enough, Jesus shows up to greet Thomas.

24 But Thomas (who was called the Twin, one of the twelve, was not with them when Jesus came. 25 So the other disciples told him, “We have seen the Lord.” But he said to them, “Unless I see the mark of the nails in his hands and put my finger in the mark of the nails and my hand in his side, I will not believe.”

26 A week later his disciples were again in the house, and Thomas was with them. Although the doors were shut, Jesus came and stood among them and said, “Peace be with you.” 27 Then he said to Thomas, “Put your finger here and see my hands. Reach out your hand and put it in my side. Do not doubt but believe.” 28 Thomas answered him, “My Lord and my God!” 29 Jesus said to him, “Have you believed because you have seen me? Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have come to believe.”

Is “seeing” and then believing an inadequate form of faith? Is it better to have faith without seeing or is seeing actually necessary in order to find faith? It’s a problem that is a little hard to figure out in the gospel of John. When people in this gospel proclaim that they have seen Jesus, or that they now “see” something–it is a confession of faith, and this is true all the way to the end of the gospel.

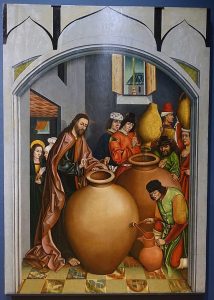

One of the biggest themes concerns seven signs described in the Gospel of John. What does John mean by the term “signs”? The signs in the Gospel of John are not just miracles to prove Jesus’ power, they have some kind of theological or symbolic meaning embedded into them. Primarily, they are signs of Jesus’ power, but they also indicate a change of attitude, a new way of having or finding faith. This messiah was God with the people–symbolized in these signs.

The Seven Signs:

- The first sign is turning water into wine. Jesus is famous for turning water into wine, and the story is only in the Gospel of John, not in the other Gospels. It is found in John 2:1-11 and the end of the story says,

“Jesus did this, the first of his signs, in Cana of Galilee and revealed his glory, and his disciples believed in him.” (when the disciples saw this, they believed)

- The second sign is the healing of the son of an official in Capernaum in John 4:46-54,

46 Then he came again to Cana in Galilee, where he had changed the water into wine. Now there was a royal official whose son lay ill in Capernaum. 47 When he heard that Jesus had come from Judea to Galilee, he went and begged him to come down and heal his son, for he was at the point of death. 48 Then Jesus said to him, “Unless you see signs and wonders you will not believe.” 49 The official said to him, “Sir, come down before my little boy dies.” 50 Jesus said to him, “Go; your son will live.” The man believed the word that Jesus spoke to him and started on his way. 51 As he was going down, his slaves met him and told him that his child was alive. 52 So he asked them the hour when he began to recover, and they said to him, “Yesterday at one in the afternoon the fever left him.” 53 The father realized that this was the hour when Jesus had said to him, “Your son will live.” So he himself believed, along with his whole household. 54 Now this was the second sign that Jesus did after coming from Judea to Galilee.”

- The third sign is found in John 5:1-15, which describes Jesus healing a paralytic man in Jerusalem at the Pool of Bethsaida. He did this on the Sabbath, which was wrong according to strict Jewish law, but Jesus tells them, “My Father is still working, and I also am working.”

- The fourth sign is found in John 6, which is the story of the feeding of the 5,000. People claimed that he was a prophet, but John goes on to say that Jesus had to leave the place where this happened, because people were coming to make him a king. The story ends, “When the people saw the sign that he had done, they began to say, “This is indeed the prophet who is to come into the world.”

- The fifth sign is also in chapter 6, and is the story of Jesus walking on the water out to the fishing boat, which is in all four gospels. The people the next day ask for a sign as tangible as manna from heaven, but Jesus tells them that they must not just want more food, but instead want the spiritual food that he, Jesus, is for them.

- The sixth sign is the healing of the blind man, found in John 9. Jesus says to the people about this occurrence,

“We must work the works of him who sent me while it is day; night is coming, when no one can work. As long as I am in the world, I am the light of the world.”

Here is, once more, the concept of light and life.

- And the seventh sign is found in the story of the raising of Lazarus in John 11. Even before raising Lazarus, Martha says to Jesus, “I believe that you are the Messiah, the Son of God, the one coming into the world.” After Lazarus had come out of the tomb, the chapter continues: “Many of the Jews, therefore, who had come with Mary and had seen what Jesus did believed in him.”

Johannine Sectarianism: who is he writing for?

One of the most important things that drives the Gospel of John is the idea of sectarianism. What is meant by sectarianism? According to sociology of religion, a sect is a sociological term that refers to any group, whether it’s religious or not, that breaks away from a larger group, and sometimes even from the rest of society. What makes a group a sectarian group is generally very firm boundaries about who is in and out of the group, what the rules are, and who is in charge. It is not, however, the same thing as a cult.

John’s audience, the people he is writing for, seems to be a very sectarian group. There are stark divisions in John’s descriptions of people during the gospel narrative– there are clear insiders, outsiders; there are children of light and children of darkness, there are children of God and children of Satan. There is no in between, there is no gray area, one is either in or out, so scholars define this idea of people being divided in some way, seen all through John’s gospel, by talking about Johannine sectarianism– the insider-outsider divisions.

Look at one place where that division between “in” and “out” occurs in chapter 9. This is a story–one of the seven signs found in John– about Jesus healing a man born blind. The story starts out in a traditional manner, with the miracle taking place and people marveling at this miraculous occurrence.

But then in chapter 9:10 the the people want to know more, and keep saying in response to his healing:

“Then how were your eyes opened?” He answered, “The man called Jesus made mud, spread it on my eyes, and said to me. ‘Go to Siloam and wash.’ Then I went and washed and received my sight.” They said to him, “Where is he?” He said, “I do not know.” They brought him to the Pharisees, the man who had formerly been blind. Now it was the Sabbath day.”

In all of the Gospels, many stories seem to be straightforward miracle stories, and other stories seem to be nature miracles–power over nature in some way.

But then there are some miracle stories that are also conflict stories. In this particular story, the reader is told that someone was healed. The really important part of the story, however, was not that the man was healed but that he was healed on the Sabbath. That healing on the Sabbath starts a conflict between Jesus and Jewish leadership about what one is permitted to actually do on the Sabbath. By verse 13 of chapter 9 what started out as simply a healing story with some symbolic meaning (because the man is blind and he comes to see, and those are big important themes for the Gospel of John) now has become a conflict story over the rules and meaning of the Sabbath.

The man who was healed tells the story again to the Pharisees in verse chapter 9:17:

“So they said again to the blind man [this is the Pharisees talking], “What do you say about him? It was your eyes he opened.” He said, “He is a prophet.” The Jews did not believe that he had been born blind and had received his sight until they called the parents of the man who had received his sight and asked them, “Is this your son, who you say was born blind? How then does he see?” His parents said, “We know that this is our son, and that he was born blind; but we do not know how it is that he now sees, nor do we know who opened his eyes. Ask him; he is of age. He will speak for himself.” His parents said this because they were afraid of the Jews.”

This last statement should stop the reader! All the people in this story are Jews. Jesus is a Jew, the blind man is a Jew, his parents are Jews– they are all Jews. Why is that phrase included about people being afraid of “the Jews”? And the answer? “For the Jews had already agreed that anyone who confessed Jesus to be the Messiah would be put out of the synagogue.”

That statement is outright anachronistic. There was no movement going on during the life of Jesus where anybody who confessed Jesus to be the Messiah would be excommunicated from the synagogue– that just did not happen during that period of time. There were a number of groups of people who thought that some kind of Messiah was around at the time of Jesus, not just those who followed Jesus. The Jews hated the Roman occupation, and were desperate for a messianic figure to liberate them, as King David had done for Israel in the past.

Jesus of Nazareth was not the only roaming preacher in first century Israel! There were debates about this issue of a current messianic figure among the religious leadership of the early first century temple and synagogues, but there were not any religious leaders saying, “well, anybody who claims that Jesus of Nazareth is the Messiah will be excommunicated.” Very few of them had even heard of this man!

Driving Jesus-followers out of the synagogues may have been going on decades later when this Gospel was written, however. And that is the point behind this writing–the gospel of John was written for people living 70 years after the time of Jesus. The stories are pointed directly at their time and their experiences.

What is going on here with the “fear of the Jews” statement is this–what someone believes about Jesus the Messiah has to do with whether that person is allowed to stay in the synagogue late in the first century. If someone takes Jesus to be only a prophet, they might be allowed to stay in the synagogue. If a person confesses that Jesus is the long awaited Messiah, it is possible that they may be kicked out of the synagogue. The Jesus followers had gained some visibility and notoriety by that time, and eventually they were no longer considered real Jews. That is the basic conflict of this story of healing the blind man. It defines the division between who is “in” and who is “not in”.

If one continues in chapter 9, the narrative goes into more and more conflict.

Look at verse 30 and following:

“The man answered, “Here is astonishing thing! [this is the man born blind who now sees] You do not know where he comes from, and yet he opened my eyes. We know that God does not listen to sinners, but he does listen to one who worships him and obeys his will. Never since the world began has it been heard that anyone opened the eyes of a person born blind. If this man were not from God he could do nothing.” They answered him, “You were born entirely in sins, and are you trying to teach us?” And they drove him out. Jesus heard that they had driven him out, and when he found him, he said, “Do you believe in the Son of Man?” He answered, “And who is he sir? Tell me so that I might believe in him.” Jesus said to him, “You have seen him, and the one speaking with you is he.” He said, “Lord I believe.” And he worshipped him. Jesus said, “I came into this world for judgment so that those who do not see may see–” [Now is Jesus still talking just about blind people? No– the whole story was an allegory.] “–and those who do see may become blind.” Some of the Pharisees near him heard this and said to him, “Surely we are not blind, are we?” Jesus said to them, “If you were blind, you would not have sin. But now that you say, ‘We see,’ your sin remains.”

So John tells the story showing the blind man as someone who comes to faith in Jesus as the Messiah. But if the blind man really confesses that to be true, he is going to be thrown out of the synagogue. So what happens? He voluntarily leaves the synagogue and he joins up with the followers of Jesus. His confession makes him a member of the church for whom John is writing. There are other people who suspect that Jesus may well be the messiah, they may even want to confess him to be the messiah, and they don’t do so because they’re afraid about being excommunicated from the synagogue. Who is “in”? The ones who confess Jesus as messiah and willingly leave the synagogue. They are now “in” the church instead.

Johannine Christology

Notice how this story in chapter 9 has become an allegory for what is going on in the time of the writing of the gospel of John itself. The Gospel writer is telling a story about a blind man but he is also telling a story about the conflict that his church is having with the local synagogue, late in the first century CE. See, too, that it is Jesus who brings about the division that takes place. What’s the main reason for the division? Christology.

There are and were different Christologies found in the gospels, both in these gospels from the Biblical canon and in those gospels not included. Christology concerns what is believed to be true about the nature of Jesus Christ. Is he just human? Is he God? Is he some of both? Is he more than a prophet? Is he only a prophet? Is he more than a moral teacher? Is he only a moral teacher? Is he the Son of God? Is he equal to God the Father? All of these are options for belief, and the first several hundred years of Christianity is all wrapped up in which of the many different options believed to be true about Jesus end up being the “right” ones. What ends up being the idea considered orthodoxy within Christianity? The Gospel of John shows this very theme being emphasized.

Look at John 5:19

Jesus said to them, “Very truly I tell you, the Son can do nothing on his own but only what he sees the Father doing. For whatever the Father does the Son does likewise. The Father loves the Son and shows him all that he himself is doing. And he will show him greater works than these so that you will be astonished. Indeed, just as the Father raises the dead and gives them life, so also the Son gives life to whomever he wishes. The Father judges no one but has given all judgment to the Son so that all may honor the Son just as they honor the Father. Anyone who does not honor the Son does not honor the Father who sent him. Very truly I tell you, anyone who hears my word and believes him who sent me has eternal life and does not come unto judgment but has passed from death to life.”

Look at 5:18, right before that:

For this reason the Jews were seeking all the more to kill him because he was not only breaking the Sabbath but was also calling God his own Father…

The very next phrase in 5:18 is, “thereby making himself equal to God.”

The Gospel writer is editorializing because this is what he believes Jesus to be. He believes that not only is Jesus God’s Son in some kind of derivative sense, he believes that by saying that Jesus is God’s Son, he is then actually equal to God the Father.

Look at John 8:58

Jesus said to them, “Very truly I tell you, before Abraham was I am.” So they picked up stones to throw at him.

It is interesting to see that all Jesus says is, “I am”. That is the declaration of what God is, when God says, “I am,” to Moses.

This is the very name of God, which those who are non-Jewish say as Yahweh, and the name has only four letters in Hebrew. In an English Bible they are usually translated by the term “Lord” in small capital letters. But according to pious Jewish usage, one never pronounces those 4 letters, so one would say something like “the Lord” (seen in Greek as Adonai) as a substitute. And so that phrase “the Lord” is used in the English translation. Scholars think that the best translation for those four letters YHWH, as they occur in Exodus, is about being-ness and are generally translated “I am.” So the translation of the name of God is “I am”.

There are seven “I am” sayings in the gospel of John. The Greek term “ego eimi” really is an intentional method of referring to the “I am” declaration of God’s name used by God in Exodus. These images in the “I am” statements are all symbolic ways of Jesus declaring his divine nature. There are scholars who also say that they are ways that these statements contrast Jesus with the religious authorities of the time, who are portrayed variously as uncaring, haughty, and more worried about earthly concerns and not the spiritual well being of the people. These “I am” statements are found in these places:

- “I am the bread of life.” John 6:35

- “I am the light of the world.” John 8:12

- “I am the gate for the sheep.” John 10:7

- “I am the resurrection and the life.” John 11:25

- “I am the good shepherd.” John 10:11

- “I am the way, the truth, and the life.” John 14:6

- “I am the true vine.” John 15:1, 5

All of the “I am” sayings are ways for Jesus to talk about his divine nature, to use metaphor to describe how he, as God, relates to the people. He is bread, light, the way, life. That’s far more radical a claim or statement than anything seen in any of the other Gospels.

In the synoptic gospels, Jesus could be called the Son of God and still not be God. Jesus could be called the Son of the Father and still not be equal to the Father. Jesus could be the Messiah and still not be divine, and Jesus could be even the Messiah and divine and still not be “I am.” In the Gospel of John, however, Jesus says “I am.” He is the one who spoke to Moses. It is no wonder that the Jews tried to stone him! There would be no divided God in Judaism–God is transcendent, beyond human comprehension. An incarnation of God is not plausible in Judaism.

Obviously the Gospel of John is very important for Christian doctrine. It’s the most Christological of the Gospels, it has the highest form of Christology and emphasizes the divine character of Jesus, rather than focusing on him being human. This reality, this change in theology from the very early years of developing Christianity, is very important to understand. This doctrine of Christianity changes how Jesus is regarded, and changes what Christian faith will look like in the years to follow.

The struggle to understand what Jesus is saying

circa 1645 CE

The writer of John sets Jesus up as being a little confusing when it comes to interpersonal communication. To understand why that seems to be the case, think about why Jesus tends to talk in complicated and often confusing ways in the Gospel of John. What does the reader need to understand about that presentation of Jesus? What is happening in the situation of the readers that would lead to John describing Jesus in this way?

Start with this story in John 3,

“There was a Pharisee named Nicodemus, a leader of the Jews, he came to Jesus by night and said to him“ Rabbi, we know that you are a teacher who has come from God, and no one else can do these signs that you do apart from the presence of God.” Jesus answered him, “Very truly I tell you, no one can see the kingdom of God without being born from above.”

Jesus does not, in the account, respond to what Nicodemus actually says, saying nothing like “Great–you got it!”. Instead Jesus responds with this very difficult sentence, “Very truly I tell you, no one can see the kingdom of God without being born from above.”

Many English translations of the Bible say, “without being born anew” instead of “without being born from above”. The problem here is that the Greek actually can be translated several ways– “being born again” or “being born all over again,” or “being born from above.” The same Greek word means all of these. This is the main place in the entire Bible in which born-again language occurs. The other Gospels don’t talk about being born again. It’s a rare metaphor in early Christianity.

Notice that this is confusing for the hearer, clearly, because Nicodemus then answers as if he heard Jesus to be saying, “being born again.”

Nicodemus said to him, “How can anyone be born after having grown old? Can one enter a second time into the mother’s womb and be born?” 5 Jesus answered, “Very truly, I tell you, no one can enter the kingdom of God without being born of water and Spirit.

So Nicodemus said to Jesus, in some confusion, “How can anyone be born after having grown old? Can one enter a second time into the mother’s womb and be born?” Did Jesus say, “Nicodemus I’m speaking metaphorically and spiritually here, you need to understand that I don’t mean particularly that someone has to be actually born physically from their mother again.” No, Jesus doesn’t say any of that. Apparently in John’s gospel, Jesus is not portrayed as intending to communicate quite that directly with Nicodemus, because Jesus says, “Truly I tell you, no one can enter the Kingdom of God without being born of water and spirit.”

What does that mean?

“What is born of the flesh is flesh, and what is born of the spirit is spirit. Do not be astonished that I said to you, ‘You must be born from above.’ The wind blows where it chooses, and you hear the sound of it but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes.”

Evangelische Kirche Oberndorf

It might help to know that the Greek word translated here “spirit” is also the Greek word which can be translated as “wind.” The Gospel of John is playing with puns and there is already two puns in this passage. One is that Greek word “being born again” –or is it “born from above”? It sounds like it may mean a little bit of both. Is this second Greek word, pneuma supposed to represent the spirit as a theological term or is it supposed to represent breath or wind? It seems to be doing double duty.

With all that about the wind blowing where it will, so it is with everyone who is born of the spirit. Nicodemus tries one more time said to him, “How can these things be?” In other words Nicodemus is saying, “Jesus, can you give me an explanation of what you’re talking about?” It is not an unreasonable request.

He continues in John 3:10-15

Jesus answered, “Are you a teacher of Israel and you do not understand these things? Truly I tell you, we speak of what we know and testify to what we’ve seen, yet you do not receive our testimony. If I had told you about earthly things and you do not believe, how will you believe if I tell you about heavenly things? No one has ascended into heaven except the one who descended from heaven, the Son of Man. And just as Moses lifted up the servant in the wilderness, so the Son of Man must be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life.”

At this point Nicodemus has apparently decided that he can’t get a straight answer to his questions. Jesus starts off in a dialogical stance with Nicodemus but never answers his questions directly, and then goes on to insult Nicodemus by questioning his credentials and knowledge, rather than just explaining what he means. This is the way Jesus sometimes talks in the Gospel of John, and the question is–why? What is the point of portraying Jesus in this fashion? Is Jesus supposed to be confusing and unsettling?

Look in John 8:31.

“Jesus said to the Jews who had believed in him.”

Notice that in the Gospel of John the Jews are talked about as if they’re something other than Jesus is. Of course Jesus is a Jew, his disciples are Jews, they’re all Jews in this story. But the term “the Jews” gets written in the Gospel of John with this idea that they are “other” and this is a reflection of the sectarianism talked about earlier.

Jesus is now talking to the Jews who believe in him. These are not the Jews who have rejected him, a very important point in the chapter. These are the Jews who now believe in him.

“If you continue in my word you are truly my disciples and you will know the truth and the truth will make you free.” They answered him, “We are the descendants of Abraham and have never been slaves to anyone. What do you mean by saying you will be made free?”

Does Jesus answered them, “Well I was speaking metaphorically. I meant that, let’s say you are slaves to sin and if you follow me, then I will make you truly free in a spiritual sense, I mean.” to help them understand? No.

It continues with verse 34:

Jesus answered them, “Very truly I tell you, everyone who commits sin is a slave to sin. The slave does not have a permanent place in the household. The son has a place there forever, so if the son makes you free, you will be free indeed. I know that you are descendants of Abraham, yet you look for an opportunity to kill me because there’s no place in you for my word. I declare what I have seen in the Father’s presence. As for you, you should do what you have heard from the Father.” They answered him, Well Abraham’s our father, we’re Jews.

Jesus said to them, “If you are Abraham’s children you would be doing what Abraham did. But now you are trying to kill me, a man who has told you the truth that I heard from God. This is not what Abraham did. You are indeed doing what your father does.” They said to him, “We are not illegitimate children, we have one father, God Himself.

So they try another tactic, well, if Jesus won’t be satisfied with Abraham as being the Father of these people, they will mention that they have God as their Father.

Jesus said to them, “If God were your Father you would love me, for I came from God, and now I am here. I did not come of my own, but he sent me. Why do you not understand what I say? Is it because you cannot accept my word? You are from your father the devil.”

They come from the devil? Why is he saying this? These are the people who supposedly believe in him! Jesus keeps trying to get through to his listeners, but it is pretty clearly getting antagonistic between he and the people at this point:

47 Whoever is from God hears the words of God. The reason you do not hear them is that you are not from God.”

and Jesus ends up the whole discussion like this. But these listeners are not done. They want to know who this man thinks he is. They think he is important, yes, but is he more important than Abraham? So the listeners attack Jesus:

“Are we not right in saying that you are a Samaritan and have a demon?”

Now they are all being antagonistic, and after some more angry exchanges, finally the chapter ends like this, with Jesus saying:

“Your ancestor Abraham rejoiced that he would see my day, he saw it and was glad.” Then the Jews said to him, “You are not yet fifty years old, and have you seen Abraham?” Jesus said to him, “Very truly I tell you, before Abraham was, I am.”

This is that strong Christological claim of Jesus being God. Jesus does not do what a good instructor is supposed to do, which is explain things more thoroughly. Jesus talks in phrases that feel a bit like riddles throughout John. When people ask him questions he responds with non-sequiturs. And then when they act like they want to believe in him he pushes them rather hard, and eventually the scenes ends up with everybody all frustrated.

The key in each of these stories in the Gospel of John is that these issues come down to Christology. Who is the person of Jesus? Each of these stories, when Jesus seems confusing at best, and people are angry or bewildered or frustrated or lost–they are all based on the claims that Jesus is God.

The people of John’s church in the late 1st century are confused, are startled by the ongoing development in the church of the idea that Jesus is God. They are people who believed in him as the messiah, and perhaps even something more than human. But was Jesus actually God, come to earth, walking and talking and eating? John portrays the people of the time of Jesus as also being confused. He can tell his readers that they are not alone in their confusion–the early believers were confused, too, but Jesus kept telling them the truth, and here is what he said. And this all leads to the reality that these beliefs will separate these Jewish believers from the synagogues. That separation, that division, is important to keep in mind.

The ongoing development of how early leaders of the faith saw Jesus is reflected in this gospel, written 15-20 years after any of the synoptic gospels.

Differences in stories between John and the Synoptics

John used a number of stories from the synoptic gospels–many of them from the period of Holy Week. But the detail and direction of those stories differs, sometimes a lot, from the earlier renditions of those stories. A little comparison is offered here about some of these stories.

The Last Supper

The Last Supper in the synoptic Gospels is a Passover meal. The Last Supper in John is not a Passover meal. In fact, also, the Last Supper in John’s gospel is not starting the institution of the Eucharist. In Christian churches the Eucharist was established in his Last Supper with his disciples, from the words “do this in memory of me.” That phrase goes back to Matthew, Mark, and Luke. The Gospel of John doesn’t have anything like that in its account of the Last Supper. There’s no place in the Gospel of John where Jesus initiates the Eucharist. He doesn’t take the cup, he doesn’t take the wine, and does not say, “do this in memory of me”.

What happens at the Last Supper in the Gospel of John? He has a foot washing ceremony. Notice again what Christian tradition has done here. The Thursday night of Holy Week is when Jesus has the Last Supper with his disciples. In many Christian churches, on the Thursday before Easter, not only will there be a communion service, but there will also be a foot washing service. This happens in imitation of Jesus’ foot washing of his disciples at the Last Supper in John. Christians have combined the Last Supper and the Eucharist establishment from the synoptic gospels, with the foot washing service from the Gospel of John, and they have been put together in one ceremony. That happens with the Christmas story in Matthew and Luke, with this passion event on Thursday night, and with the 7 Last Words of Jesus on the cross–it is a common enough occurrence. It does help explain why the Bible has 4 gospels! Combining tradition and narrative from all of the gospels sets belief and tradition in place for early Christianity.

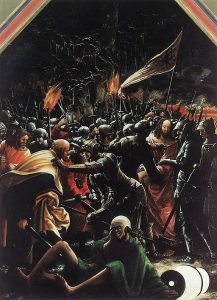

The arrest

The arrest is also very different in the synoptic Gospels from the account in John. In the synoptic gospels the soldiers come to arrest Jesus and they just arrest him. In the Gospel of John there is this scene in the middle of the night in the garden, and the soldiers come up to Jesus and they say, “We are looking for Jesus of Nazareth”, and Jesus says, “I am he”, and they all fall over on the ground. The power of him saying this knocks them all over! Eventually they get up and arrest him, but there is a strange little scene included which has Peter cutting off the ear of a slave in the struggle.

The whole scene of the arrest of Jesus thus is very different in the Gospel of John. At his trial, in the synoptic gospels, Jesus says almost nothing. Some of the synoptics say he said nothing, other synoptics say he said something, but he’s very, very quiet on the whole. In the Gospel of John he talks–he talks to Annas and Caiaphas, he carries on this whole philosophical discussion with Pilate about his kingdom and about truth. He just keeps talking and talking, making it a very different scene. Is Jesus talking here to these key religious leaders, to these Romans, or is he, through John’s editing, talking to late 1st century readers?

The Crucifixion

The accounts of the crucifixion also have some differences. According to the first three Gospels, the crucifixion takes place on the first day of Passover. In Jewish calendar reckoning, a day begins at sundown, so sundown of Thursday night is the beginning of Friday, and in the synoptic gospels that is the beginning of the Passover. The disciples and Jesus wait until sundown and they then have the Passover meal Thursday night. That is actually Friday at that point, the first day of Passover, and it is on the Friday the first day of Passover that Jesus is actually executed. It all happens very quickly–the dinner, the arrest, the trial, and the crucifixion.

That’s not the way it is in the Gospel of John. According to the Gospel of John, Jesus is not crucified on the first day of Passover, he is crucified on the day before Passover. And how does a reader know that? Because John says that they were crucifying Jesus at the same time the priests were slaughtering the lambs in the temple. This is dramatic symbolism. Right when Jesus is being slaughtered, the lambs for the Passover meal are being slaughtered. Jews in Jerusalem would take a lamb to the priest on Thursday, the priest would slaughter it, pour out the blood, and then people would take the lamb back home to cook it, and that is where and when the Passover meal takes place. According to the Gospel of John, Jesus is executed at the same time that they’re slaughtering the lambs, which means he’s not executed on the day of Passover but the day before Passover.

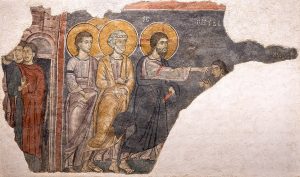

The Beloved Disciple

The last big narrative difference between the Gospel of John from the synoptics concerns the “beloved disciple”. He is Jesus’ favorite disciple in the Gospel of John. This character doesn’t exist in the other Gospels. Tradition has said that this beloved disciple is John, son of Zebedee, younger brother of James. When John, son of Zebedee, is depicted in art he’s always the depicted as a young man without a beard, very beautiful, almost feminine looking, representing the boy, this youngest disciple, that Jesus loved.

The Gospel of John does not say that this character was in fact young John, it just tells the reader that there was this beloved disciple. But he is a strong character in this Gospel and he doesn’t appear anyplace else but in this Gospel.

In all these ways, in presentation, in language use, in the character of Jesus, and more, the Gospel of John is very different from the other three Gospels. That in itself makes it really interesting to study. It shows the reader an entirely different kind of early Christianity that is developing among the churches and believers. Scholars would not understand the process of change, and the continuing transformation of Christianity, without this Gospel.

A quote from John Dominic Crossan[1] can help readers understand all this differentiation between the gospel accounts:

“What is consistent about the gospels is that they change consistent with their own theology, with their own communities’ needs. They do not change at random. If you begin to understand how Matthew changes Mark, you see it worked again and again and again. You don’t have to make up a different reason for every change. Once you understand Matthew’s theology, you can almost predict how he will change.

Let me compare Mark with John to explain how two gospels do it differently in an episode we call “the agony in the garden”. Now, there is no agony in John and there is no garden in Mark, but we call it the agony in the garden because we put them together. Mark tells the story in which Jesus, the night before he dies, is prostrate on the ground, begging God, “If this all could pass, but I will do what you want.” And the disciples all flee. Now that’s an awful picture. That makes sense to me because Mark is writing to a persecuted community who know what it’s like to die. That’s how you die, feeling abandoned by God.

Over to John. Jesus is not on the ground in John. The whole cohort of the Jerusalem forces come out – 600 troops come out to capture Jesus, and they end up with their faces on the ground in John. And Jesus says, “Of course I will do what the Father wants.” And Jesus tells them to “Let my disciples go.” He’s in command of the whole operation. You have a Jesus out of control almost in Mark, a Jesus totally in control in John. Both gospel. Neither of them are historical. I don’t think either of them know exactly what happened. Mark is writing to a persecuted church, “Here is how to die … like Jesus.” John is writing, I think, to a community that’s hanging on by its fingernails. It’s getting more and more marginalized. Its Jesus is getting more and more in control, in control of the passion, in control of Pilate. The more John’s community is out of control, the more Jesus is in control. Both … make absolute sense to me. But both are gospel.”

Jesus as seen in the New Rome that is Christian

May, Herbert G., et al. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha: Revised Standard Version, Containing the Second Edition of the New Testament and an Expanded Edition of the Apocrypha. Edited by Michael D Coogan, Oxford University Press, 2007.

Gabel, John B. The Bible as Literature: An Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2006.

White, Michael, and Helmut Koester. “The Story of the Storytellers – Importance of the Oral Tradition | from Jesus to Christ | Frontline.” Frontline: from Jesus to Christ, Public Broadcasting Service, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/religion/story/oral.html.

Pagels, Elaine, et al. “The Story of the Storytellers – the Emergence of the Four Gospel Canon | from Jesus to Christ | Frontline.” Frontline: from Jesus to Christ, Public Broadcasting Service, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/religion/story/emergence.html.

White, Michael, et al. “The Story of the Storytellers – What Are the Gospels? | from Jesus to Christ | Frontline.” Frontline: From Jesus to Christ, Public Broadcasting Service, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/religion/story/gospels.html.

Kent, C. F. (1912) Palestine in the time of Jesus, 4 B.C. – 30 A.D.: including the period of Herod, 40 – 4 B.C. [S.l.: s.n] [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2009579463/.

Grey, George. “‘The Gospel of John.’” Portland Community College, 18 Nov. 2019, https://youtu.be/79JfI68X7kk.

“The Conversion of the Roman Empire and Its Impact on the Jews.” Yad Vasehm, 13 Oct. 2020, https://youtu.be/jKX2BLqF5k8.

Dale Martin, Introduction to the New Testament, Yale University: Open Yale Courses, http://oyc.yale.edu. License: Creative Commons BY-NC-SA . Most of the lectures and course material within Open Yale Courses are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 license. Unless explicitly set forth in the applicable Credits section of a lecture, third-party content is not covered under the Creative Commons license.

- (born February 17, 1934, Nenagh, Ireland), Irish-born American theologian and former Roman Catholic priest best known for his association with the Jesus Seminar, an organization of revisionist biblical scholars, and his controversial writings on the historical Jesus and the origins of Christianity. ↵

the period or course of a life

belonging to a period other than that being portrayed.

Christology is the part of theology that is concerned with the nature and work of Jesus, including such matters as the Incarnation, the Resurrection, and his human and divine natures and their relationship

a person who embodies in the flesh a deity

the week before Easter, starting on Palm Sunday.