14 Job

Understanding The Book of Job

The book of Job addresses the age old struggle of humanity–trying to find meaning in human suffering. All peoples across the earth have tried to explain suffering. There are several challenges to previous Israelite ideas and beliefs encountered in the Book of Job. In Job we find the idea brought forth that suffering is not always some kind of punishment or consequence of wrongdoing. It is not always actually explicable.

The Book of Job is hard to date. It was composed in something similar to its current form no earlier then the sixth century BCE, but some scholars suggest that there are portions of it that seem to reflect an older oral tradition. It is a tough book to read because its conclusions seem to fly in the face of some basic religious convictions found earlier in the Bible.

It might be helpful to get feeling for an ancient argument about suffering, sometimes called “The Problem of Good and Evil”. Many of the questions found here in this philosophical struggle arise when readers get involved in the book of Job.

The classic problem of good and evil

Some of the reflection in this chapter is adapted from the Yale open course lectures by Dr. Christine Hayes. For the full course, see Yale Open Courses Introduction to the Old Testament

The Book of Job attacks the conventional piety that is clearly stated in the Book of Proverbs–that good people have good lives and bad people suffer for their bad behavior. This idea shows up in the prophets, too, that bad behavior leads to terrible consequences. The ideas in Job challenge the assumption that there is a moral world order, however.

Job’s story looks at the concept of bad things happening to good people.

Two issues arise in Job:

- First, why does God permit blatant injustice and undeserved suffering and evil to exist in the world?

- And second, are people righteous only because God will reward them for it, or are they righteous because of the intrinsic and inherent value of righteousness?

Why do bad things happen to good people?

The universal question of all people, both those of all faiths and those of no particular faith, concerns suffering and whether there is any purpose or meaning to it. A popular book from the 1980s was Rabbi Harold Kushner’s “When Bad Things Happen to Good People”. Here is an article in Psychology Today by psychiatrist Dr. Ralph Lewis[1] looking at that very question: Why do Bad Things Happen to Good People?

Looking at Job as a literary composition, the book contains two elements–a prose beginning and end, and a poetic interior. The different literary approaches do slightly different things with the meaning behind this story.

First comes the prose story, which provides a beginning framework for the book in chapters 1 and 2. The prose approach then returns part way through chapter 42 at the end of the book. All by itself, the prose story can tell the whole basic story. Into this prose framework, however, a large poetic section of dialogue and speeches has been inserted by the anonymous Israelite author.

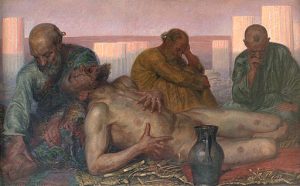

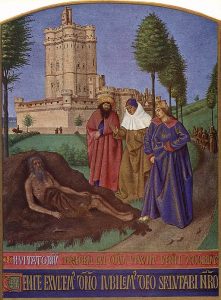

The prose narration at the beginning of the book–this prologue– concerns a scrupulously righteous man named Job who is afflicted by horrendous calamity. This story is likely a standard Ancient Near Eastern folktale. The story is not set in Israel, either, it is set in Edom. Job is an eastern magnate who dwells in the country of Uz. But the Israelite author uses this older Ancient Near Eastern legend about a man named Job for his own purposes and makes some changes in order to talk about the big issues surrounding human suffering.

Chapters 1 and 2 contain the prose prologue about the pious and prosperous Job and his devastation, which is the result of a challenge put to God. At the end of that prologue, Job has three friends who come to sit with him in silence for seven days. The silence doesn’t last very long, however, because the book moves into the large poetic section that extends from chapter 3 all the way to chapter 42, verse 7. And here the friends are anything but silent!

Job is seen refuting the idea of retributive justice endorsed by his friends.

First in the poetic section is a dialogue between Job and his three friends that goes from chapter 3 to chapter 31, verse 40. This portion can be divided into three cycles of speeches. Job opens each cycle and then his friends speak in a regular pattern, taking turns interpreting what causes Job to suffer.

At first, the friends seek to comfort Job and to explain his suffering but they become increasingly harsh as time goes on, ultimately showing a callous contempt for Job’s condition. This section closes with the speech by Job in chapters 29 to 31. In this section he laments the loss of his past, pleasant life. He protests his innocence, he calls on God to answer.

But at this point Elihu, this previously unannounced fourth friend, appears. He gives four speeches from chapters 32 to 37. He admonishes Job; he defends God’s justice.

And then this is followed by a poetic discourse between God, who poses a series of rhetorical questions, and Job, who appears contrite. This Job/God exchange runs until midway through chapter 42.

Finally, there’s a concluding prose epilogue that vindicates Job. God criticizes Job’s friends, and then in a rather unexpected “happy ending”, Job is restored to his fortunes and finally experiences a peaceful death.

Interpreting the Prose Prologue in the Book of Job

The story opens in the prologue by introducing Job. He is said to be a blameless and upright man. He fears God and he shuns evil, says chapter 1, verse 1. The moral virtue and innocence of Job is established in the opening line as a non-negotiable narrative fact. And yet this Job is to become the victim of a challenge issued by “the satan” in the heavenly counsel. It is written “the satan” deliberately. The satan is certainly not the devil. There’s no such notion in the Hebrew Bible. The phrase, “the satan,” occurs four times in the Hebrew Bible, here in Job and in Numbers 22 and Zechariah 3.

“The satan” is simply a member of the divine counsel — one of God’s minions whose function it is to investigate affairs on earth and to act as a kind of prosecuting attorney. The satan has to bring evildoers to justice. It is only in later Jewish, and then especially in Christian thought, that the term loses the definite article — it goes from “the satan” which means “the prosecutor” essentially, the prosecuting attorney — and becomes a proper name, Satan, used for an enemy or opponent of God.

This later concept of the devil, or Satan, develops as a means of explaining evil without attributing it to God, but that isn’t the function of the satan here in this prologue. The satan works for God and when Yahweh boasts of the pious Job, the prosecuting angel wonders, as his portfolio requires him to do, whether Job’s piety is sincere. Perhaps Job is motivated by self-interest. Since he’s been blessed with such good fortune and prosperity, he is naturally pious and righteous, but would his piety survive affliction and suffering? Deprived of his wealth would it be more likely that Job would curse God instead of acting devout?

Would Job curse God directly? God is quite confident that Job’s piety is not superficial, it is not driven by the desire for reward, and so God permits the satan to put Job to the test. Job’s children are killed, his cattle are destroyed, his property is destroyed, but Job’s response (still in the prologue prose version) in chapter 1:21 is, “Naked I came from my mother’s womb and naked I shall return; God gives and God takes away, may the name of the Lord be blessed.”

The narrator then adds in the next verse (22), “In all this Job did not sin or impute anything unsavory to God.” And God again praises Job to the satan, saying, “And still he holds on to his integrity, so you incited me to destroy him for nothing.”

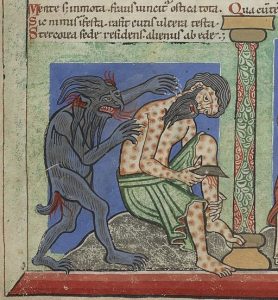

So the satan proposes increasing the suffering, and God agrees on the condition that Job’s life be preserved.

The satan then strikes Job’s body with these terrible painful sores, trying to crush his spirit and in chapter 2:9 Job’s wife rages, “Do you still hold on to your integrity? Bless God,” (curse God) “and die”. But still Job will not sin, he will not curse God, he insists on remaining virtuous and he responds, “Shall we receive good at the hand of God and shall we not receive evil?”

So at first glance it would appear that Job accepts his bitter fate. But after the first round of suffering the narrator observed that “in all this Job did not sin with his lips or impute anything unsavory to God,” and now later the narrator only observes, “in all this Job did not sin with his lips.” Not with his lips perhaps, but in his heart did he impute unsavory things to God?

If this prologue were to lead directly to the conclusion of the folktale in chapter 42 with nothing in between, the story would conclude with Job being rewarded fully for his patience and steadfast loyalty and his household and his belongings being restored to him twice over. The folktale standing alone could be read as the story of an innocent man tested, who accepts his fate. He retains his faith, and he is rewarded for this. This may have been an early version of the story.

Standing alone, the tale appears to reflect the values and the conventional piety of the earlier Wisdom literature and of the Deuteronomistic school. But the folktale doesn’t stand alone. The anonymous author of the Biblical Job uses the earlier legend concerning the righteous man Job as a frame for his own purposes, and the hint at the end of the prologue that Job perhaps is beginning to impute unsavory things to God points forward to this extensive poetic dialogue that follows.

Poetic Speech Cycles in the Book of Job

Here in this section are Job’s accusations against God. Job charges God with gross mismanagement of the world and eventually denies the existence of a moral order altogether. The two types of material in the book, the prose frame with the poetic dialogue in the middle, are clearly in tension with each other as far as forming conclusions goes. And yet the one form shapes the reading of the other.

Job is innocent. That’s a non-negotiable narrative fact and because Job’s righteousness is undeniable, clearly Job’s friends are lying when they say Job must be suffering for some hidden sin. And Job’s self-defense, that he hasn’t deserved the suffering, is correct.

Although Job doesn’t exactly curse God in his first speech, he does curse the day of his own birth. And in a passage that alludes repeatedly to creation, Job essentially curses all that God has accomplished as creator of the cosmos. Job wishes that he were dead, and at this point he does not even ask why this has happened to him, he only asks why he should be alive when he prefers death.

Eliphaz’s reply is long and elaborate. He seems to offer comfort but eventually Eliphaz says in chapter 4:7-8.,

“Think now, what innocent man ever perished? / Where have the upright been destroyed? / As I have seen, those who plow evil / And sow mischief reap them”

So Eliphaz is handing Job the standard line of Biblical Wisdom literature as exemplified by the book of Proverbs, the belief in a system of divine retributive justice. By definition there can be no undeserved suffering. The implication is that Job has deserved this suffering — a thought that apparently had not occurred to Job — and the question of undeserved suffering is now going to dominate the rest of the discussion.

Job’s second speech is full of wildly contradictory images that may reflect the shock and the pain and the rage that now overwhelm him. He seems to be haunted by Eliphaz’s connection of his suffering with some sin and so Job turns to address God directly. He admits he’s not perfect but surely, he objects, he doesn’t deserve such affliction.

Chapter 8 contains Bildad’s speech, and it is tactless and unkind. Bildad says in 8:3-4 ,

“Will God pervert the right? / Will the Almighty pervert justice? / If your sons sinned against Him, / He dispatched them for their transgressions”

In other words, God is perfectly just and ultimately all get what they deserve. Your children, Job, must have died because they sinned, says Bildad, so just search for God and ask for mercy.

The friends’ speeches lead Job to the conclusion that God must be indifferent to moral status. God doesn’t follow the rules demanded of human beings. This is chapter 9:22,

“God finishes off both perfect and wicked.”

When Job complains in chapter 9:17,

“He wounds me much for nothing,”

Job is echoing God’s own words to the satan in the prologue, when God says to the satan “you have incited me to destroy him for nothing,” and this shows that Job is right.

Example: the Trial of God

There is a play, written by Nobel Laureate and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel called the Trial of God. Wiesel says that he witnessed 3 men discussing God’s accountability while he was in Auschwitz. Here is an article about this from the time of the play’s publication: Yes, We Really Did Put God on Trial

There has been a great deal of dialogue within the Jewish community (and other places, of course, too) concerning the Holocaust. A quote from an article dated August 7, 2016 by Daniel Deforest London[2] says, “About a month ago, one of the most famous Holocaust survivors Elie Wiesel passed away at age 87. Upon receiving the Nobel Peace Prize for speaking out against violence and racism and standing up for human rights, Wiesel was asked why he believed God permitted the Holocaust. Wiesel said,

“I have not answered that question, but I have not lost faith in God. I have moments of anger and protest. Sometimes I’ve been closer to God for that reason.” With these words, I hear Wiesel expressing this particularly Jewish kind of prayer; a prayer practiced not only by Jews after the Holocaust but also by the ancient Hebrew prophets, including the great prophet Isaiah, who in our reading this morning, invites us into this same kind of prayer when he writes: “Come, now, let us argue it out, says the Lord.” The Scriptures themselves invite us to argue with God, to bring to him our anger and protest, our complaints and laments. Although this way of engaging God may sound strange to some of us, we see it all throughout Scripture…”

Job calls for the charges against him to be published, and then he hurls countercharges in a suit against God. Charges follow against God, accusing God of unworthy conduct, of spurning various creatures while smiling on the wicked, even on God scrutinizing Job even though God knows Job to be innocent.

Here Job arraigns God in a “riv” style lawsuit, and yet, Job asserts, since God is God and not a human adversary, there’s really no fair way for the lawsuit between them to be tried or arbitrated. “Man cannot win a suit against God,” says Job in chapter 9:2. Job is powerless in the face of this injustice.

These ideas all finally find expression in Job 10:1-7

“I loathe my life;

I will give free utterance to my complaint;

I will speak in the bitterness of my soul.

2 I will say to God, Do not condemn me;

let me know why you contend against me.

3 Does it seem good to you to oppress,

to despise the work of your hands

and favor the schemes of the wicked?

4 Do you have eyes of flesh?

Do you see as humans see?

5 Are your days like the days of mortals,

or your years like human years,

6 that you seek out my iniquity

and search for my sin,

7 although you know that I am not guilty,

and there is no one to deliver out of your hand?” (NRSV)

Job repeats his wish to die, this time less because of his suffering and more because his worldview has collapsed. He sees that divine power is utterly divorced from justice and that’s a fundamental Biblical assumption subverted.

But Job’s words only seem to urge his friends on. Eliphaz had implied that Job was a sinner. Bildad had baldly asserted that his sons had died for their sins and now Zophar claims that, actually, Job is suffering less then he deserves. Job isn’t persuaded by any of this. He is not persuaded that he has sinned or, more precisely, that he has sinned in proportion to the punishment he is now suffering. God is simply unjust. The Job of this poetic dialogue portion of the book is hardly patient or pious. He is angry, he is violent, he argues, he complains, and vehemently insists upon his innocence.

In the fourth speech by Job — this is the speech that opens the second cycle of speeches — Job appeals to creation. God’s controlling power is arbitrary and unprincipled. God interferes with the natural order, interferes with the human order, and this is itself a subversion of the Genesis portrait of creation as a process whose goal and crown is humankind. Again, Job demands a trial. He demands a trial in the widely quoted and mistranslated verse — this is Job 13:15:

“He may well slay me. I may have no hope — but I must argue my case before Him.”

In other words, Job knows that he can’t win but he still wants his day in court. He wants to make his accusation of God’s mismanagement. He wants to voice his protest even though he knows it will gain him nothing.

In his second speech Job fully expects to be murdered, not executed, but murdered by God and hopes only that the evidence of his murder will not be concealed. He says in chapter 16:18,

“Earth, do not cover my blood”.

Job’s third speech reiterates this desire, the desire that the wrong against him not be forgotten.

In chapter 19:23-24 he says:

“Would that my words were written, would that they were engraved in an inscription, with an iron stylus and lead, forever in rock they were incised,”

Job’s three speeches in the second cycle become increasingly emotional, and for their part the speeches of his friends in this cycle become increasingly cruel. Their insistence that suffering is always a sure sign of sin seems to justify hostility towards, and contempt for, Job. He’s now depicted as universally mocked and humiliated, despised and abused. One cannot help but see in this characterization of Job’s so-called friends an incisive commentary on the callous human propensity to blame the victim, and to do so lest any individual’s tidy and comfortable picture of a moral universe in which the righteous do not suffer should come apart at the seams as Job’s has.

Job opens the third cycle of speeches urging his friends to look, to really see his situation, because if they did they would be appalled. Job’s situation looked at honestly requires the admission that God has done this for no reason and that the friends’ understanding of the world is a lie. Job asserts baldly: there is no distributive justice, there’s no coherent or orderly system of morality in this life or any other. There is no concept of an afterlife, after all, in the Hebrew Bible.

Chapter 21:7-26

“Why do the wicked live on,

reach old age, and grow mighty in power?

8 Their children are established in their presence,

and their offspring before their eyes.

9 Their houses are safe from fear,

and no rod of God is upon them.

10 Their bull breeds without fail;

their cow calves and never miscarries.

11 They send out their little ones like a flock,

and their children dance around.

12 They sing to the tambourine and the lyre,

and rejoice to the sound of the pipe.

13 They spend their days in prosperity,

and in peace they go down to Sheol.

14 They say to God, ‘Leave us alone!

We do not desire to know your ways.

15 What is the Almighty, that we should serve him?

And what profit do we get if we pray to him?’

16 Is not their prosperity indeed their own achievement?

The plans of the wicked are repugnant to me.17 “How often is the lamp of the wicked put out?

How often does calamity come upon them?

How often does God[c] distribute pains in his anger?

18 How often are they like straw before the wind,

and like chaff that the storm carries away?

19 You say, ‘God stores up their iniquity for their children.’

Let it be paid back to them, so that they may know it.

20 Let their own eyes see their destruction,

and let them drink of the wrath of the Almighty.

21 For what do they care for their household after them,

when the number of their months is cut off?

22 Will any teach God knowledge,

seeing that he judges those that are on high?

23 One dies in full prosperity,

being wholly at ease and secure,

24 his loins full of milk

and the marrow of his bones moist.

25 Another dies in bitterness of soul,

never having tasted of good.

26 They lie down alike in the dust,

and the worms cover them.” (NRSV)

But the friends can’t look honestly at Job; they can’t admit that a righteous man suffers horribly.

By the end of the third cycle Job is ready and eager for his trial, but he can’t find God. Job’s final speech in the third cycle focuses on this theme of divine absence. God is irresponsibly absent from the world and the result is human wickedness. So from the idea that God is morally neutral or indifferent, Job has moved to the implicit charge that God is responsible for wickedness. God rewards wickedness and causes wickedness by a total absence and failure to govern properly. God is both corrupt and a corrupter of others. Job says; “If it is not so, who will prove me a liar and bring my words to naught.”

Yet, even in the depths of his anguish, and even though he is now convinced that God does not enforce a moral law in the universe, Job clings to one value: that righteousness is a virtue in and of itself. Even if it brings no real reward, Job will not give up his righteousness. Face to face with the shocking insight that good and evil are met with indifference by God, that righteousness brings no reward and wickedness no punishment, Job, although bitter, refuses to succumb to a moral nihilism.

He says in chapter 27:2-6:

“As God lives, who has taken away my right,

and the Almighty, who has made my soul bitter,

3 as long as my breath is in me

and the spirit of God is in my nostrils,

4 my lips will not speak falsehood,

and my tongue will not utter deceit.

5 Far be it from me to say that you are right;

until I die I will not put away my integrity from me.

6 I hold fast my righteousness, and will not let it go;

my heart does not reproach me for any of my days.” (NRSV)

These last lines recall the words of God and the satan in the prelude. The satan had said that a man will not hold on to virtue or to righteousness in the face of suffering. He will give everything away for his life. So this narrative set-up guides and influences the interpretation of Job’s statement. Although he is losing his life, Job says that he maintains his integrity just as God had scolded the satan in chapter 2:3 which, again, reads, “Still he holds onto his integrity. You have incited me to destroy him for nothing.”

So in his darkest, most bitter hour with all hope of reward gone, Job clings to the one thing he has — his own righteousness. In fact, when all hope of just reward is gone then righteousness becomes an intrinsic value.

So for all their differences in style and manner, the patient Job of the prose legend and the raging Job of the poetic dialogue are basically the same man. Each ultimately remains firm in his moral character, clinging to righteousness because of its intrinsic value and not because it will be rewarded. Indeed, Job knows bitterly that it will not be rewarded.

At the end of his outburst, Job sues God. He issues God a summons and he demands that God reveal to him the reason for his suffering. Job pronounces a series of curses to clear himself from the accusations against him, specifying the sins he has not committed and ending, as he began, in chapter 3, with a curse on the day of his birth.

Now come a response from an unannounced stranger, Elihu. He is the only one of the four interlocutors to refer to Job by name. He repeats many of the trite assertions of Job’s friends. He does hint, however, that not all suffering is punitive. He also hints that contemplation of nature’s elements can open the mind to a new awareness of God, and in these two respects, Elihu’s speech moves us towards God’s answer from the storm.

Example: Can we forgive?

An interview with Krista Tippet on the radio broadcast OnBeing with Elie Wiesel[3]: Evil, Forgiveness, and Prayer

The prayer he writes in his book One Generation After says some of what might apply to the book of Job:

“I no longer ask You for either happiness or paradise; all I ask of You is to listen and let me be aware and worthy of Your listening. I no longer ask You to resolve my questions, only to receive them and make them part of You. I no longer ask You for either rest or wisdom, I only ask You not to close me to gratitude, be it of the most trivial kind, or to surprise and friendship. Love? Love is not Yours to give. As for my enemies, I do not ask You to punish them or even to enlighten them; I only ask You not to lend them Your mask and Your powers. If You must relinquish one or the other, give them Your powers, but not Your countenance. They are modest, my prayers, and humble. I ask You what I might ask a stranger met by chance at twilight in a barren land. I ask You, God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, to enable me to pronounce these words without betraying the child that transmitted them to me. God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, enable me to forgive You and enable the child I once was to forgive me too. I no longer ask You for the life of that child, nor even for his faith. I only implore You to listen to him and act in such a way that You and I can listen to him together.”

God’s Response in the Book of Job

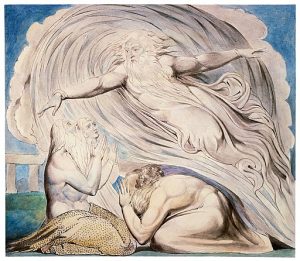

So in the climatic moment, God answers Job in an extraordinary theophany, or self-manifestation. In chapter 38 when God speaks out of the tempest or whirlwind,

“Who is this who darkens counsel, speaking without knowledge?”

is God referring to Job, to Elihu, to the three friends, or to all of them? God has heard enough, it is now God’s turn to ask questions, the answers to which are clearly implied, as these are obviously rhetorical questions.

In Job 38:1-7–

“Then the Lord answered Job out of the whirlwind:

2 “Who is this that darkens counsel by words without knowledge?

3 Gird up your loins like a man,

I will question you, and you shall declare to me.4 “Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth?

Tell me, if you have understanding.

5 Who determined its measurements—surely you know!

Or who stretched the line upon it?

6 On what were its bases sunk,

or who laid its cornerstone

7 when the morning stars sang together

and all the heavenly beings shouted for joy?” (NRSV)

God continues throughout this chapter with these rhetorical questions, questions regarding the animals, their various powers and attributes, the glories of creation, asking whether Job was there when all this creating and activity took place.

One senses that the questions are irrelevant to what Job really wants to hear from God. Job has posed some very specific challenges to God. Job has asked, “Why am I suffering? Is there a pattern to existence?” God’s refusal to answer these challenges seems to be a way of saying that there is no answer. Is this all God’s way of saying that justice is beyond human understanding?

Or is this theophany of God in nature and the focus on creation, an implicit assault on the fundamental belief within the Israelite religion that God is known and made manifest through interactions with humans, and that God rewards and punishes in historical time. This set of questions from God makes the earlier Israelite belief of retributive justice seem rather small and far too concrete.

The monotheistic revolution made a break from mythological conceptions of the gods as indistinguishable from various natural forces. Yahweh wasn’t another Ancient Near Eastern or Canaanite nature god but a wholly transcendent power known not through the involuntary and recurring cycles of nature but more through freely willed and non-repeating actions in historical time. Such a view of God underwrites the whole system of divine retributive justice.

Only an essentially good God who transcends and is unconstrained by natural forces can establish and administer a system of retributive justice, dealing out punishment and reward in response to the actions of humans in time.

Is the author of Job suggesting that history and the events that befall the just and the unjust are not the method of revealing God’s power? Is God a god of nature after all, encountered in the repeating cycles of the natural world and not in the unpredictable and incoherent arena of human history and action?

God’s direct speech to Job in 40:8, 40, verse 8 says this.

“Would you impugn my justice? / Would you condemn me that you be right?”

God says that the friends Job were wrong. Job’s friends erred because they assumed that there’s a system of retributive justice at work in the world and that assumption led them to infer that all who suffer are sinful, a blatant falsehood. But Job also errs, as he assumes that although there isn’t a system of retributive justice, there really ought to be one. It is that assumption that leads him to assume that suffering is a sign of an indifferent or wicked God, so that is equally a falsehood. Job needs to move beyond the concept, found in Genesis and beyond, that says that humankind is the goal of the entire process of creation.

The book of Job seems to suggest that God as creator defies all of this attempting to explain everything in a tidy and clear manner. In a nutshell, God refuses to be seen as a moral accountant. This idea of God as a moral accountant is responsible for two major errors: the interpretation of suffering as an indicator of sin, or the accusation of injustice as it applies to God. In his final speech, Job confesses to a new firsthand knowledge of God that he lacked before, and as a result of this knowledge Job repents in chapter 42:6.,

“Therefore, I recant and relent, / Being but dust and ashes,”

What is he repenting of? Certainly not of sin; God has not upheld the accusations against Job. God states explicitly that the friends were wrong to say Job had sinned. But God has indicated that guilt and innocence, reward and punishment are not what this is all about, and while Job had long been disabused of the notion that the wicked and the righteous actually get what they deserve, he nevertheless had clung to the idea that ideally they should. And it is that mistaken idea that this should be the case the idea that led him to ascribe wickedness to God, and so it is that thinking that God is unjust that Job now recants.

With this new understanding of God, Job is liberated from what he would now see as a false expectation raised by the Deuteronomistic notion of a covenant relationship between God and humankind, enforced by a system of divine justice. The covenant is not about human action, but about a relationship. Neither is divine justice concerned with human action.

At the end of the story Job is fully restored to his fortunes. God asserts he did no evil and the conventional and clear Deuteronomistic view of the three friends is clearly denounced by God. God says of the friends in 42:7–

“They have not spoken of me what is right as my servant Job has,”

For some, the happy ending seems anticlimactic, a capitulation to the demand for a happy ending of just desserts that runs counter to the whole thrust of the book, and yet in a way the ending is fitting. It is the last in a series of reversals that subverts our expectations. Suffering comes inexplicably, so does restoration; blessed be the name of the Lord.

God doesn’t attempt to justify or explain Job’s suffering and yet somehow by the end of the book, our grumbling, embittered, raging Job is satisfied. Perhaps Job has realized that automatic reward and punishment would make it impossible for humans to do good for purely disinterested motives. It is precisely when righteousness is seen to be absurd and meaningless that the choice to be righteous paradoxically becomes meaningful.

“The Problem of Evil: Crash Course Philosophy #13.” Crash Course, 9 May 2016, https://youtu.be/9AzNEG1GB-k.

May, Herbert G., et al. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha: Revised Standard Version, Containing the Second Edition of the New Testament and an Expanded Edition of the Apocrypha. Edited by Michael D Coogan, Oxford University Press, 2007.

Gabel, John B. The Bible as Literature: An Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2006.

“Wiesel: Yes, We Really Did Put God on Trial.” Thejc.com, The Jewish Chronicle, 19 Sept. 2008, https://www.thejc.com/news/uk/wiesel-yes-we-really-did-put-god-on-trial-1.5056.

“Evil, Forgiveness, and Prayer: Elie Wiesel.” The On Being Project, 2 July 2020, https://onbeing.org/programs/evil-forgiveness-prayer-elie-wiesel-2/.

Lewis, Ralph. “Why Do Bad Things Happen to Good People?” Psychology Today, Sussex Publishers, 19 Oct. 2019, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/finding-purpose/201910/why-do-bad-things-happen-good-people.

References

- Ralph Lewis, M.D., is a psychiatrist at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto, Canada; an assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Toronto; and a psycho-oncology consultant at the Odette Cancer Centre in Toronto. His clinical work focuses on youth psychiatry and psycho-oncology. Dr. Lewis helps people seeking meaning in the face of severe and tragic adversity, in addition to extensive experience with complex and subtle psychiatric and psychological conditions. He is interested in the unreliability of intuition and subjective perception in shaping our explanations and beliefs, and the neural basis of motivation and purposiveness. ↵

- Daniel DeForest London is an Episcopal priest, serving as the rector of Christ Episcopal Church in Eureka CA. He earned his PhD in Christian Spirituality at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley CA. He teaches courses on spirituality, ethics, and mysticism and is an Associate of the Order of the Holy Cross and the Community of the Transfiguration. https://deforestlondon.wordpress.com/ ↵

- Elie Wiesel was a writer, professor, political activist, and Holocaust survivor. He received the Congressional Medal of Honor and the Nobel Peace Prize, and was Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities at Boston University. ↵

a visible manifestation to humankind of God or a god.