7 Genesis: Abrahamic Origins

The Abrahamic Beginnings: Creation of Jews, Christians and Muslims

When people refer to the Abrahamic religions they are usually thinking of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. There are, in fact, more Abrahamic religions, such as the Baha’i Faith, Yezidi, the Druze, the Samaritans, and Rastafarians who use the Abrahamic story. Because this is a text about the Bible, the focus here is on the work found in Jewish and Christian perspectives. Some insight and assistance comes from the work of Anna Sapir Abulafia [1] In this section there is also material from Christine Hayes of Yale[2] Both have materials on the web that are Creative Commons licensed. They are a wonderful resource.

The term ‘Abrahamic’ highlights the important role Abraham plays in each of these faiths. Jews, Christians and Muslims look to their sacred texts to find the story of Abraham and his descendants and how that story has been interpreted through the ages. Abraham’s story unfolds in Genesis, the first book of the Hebrew Torah. Abraham is referred to over and over again throughout the Hebrew Bible, as well as in post-Biblical rabbinical materials interpreting the Bible called Midrash. For Christians, the Hebrew Bible is called the Old Testament, the precursor of the New Testament, that narrates the birth, ministry, death and resurrection of Jesus as well as the life and preaching of the earliest followers of Jesus. For Christian understandings of Abraham, the Letters of Paul are of particular importance.

Learning about Abraham: a more general approach

You might find it interesting to listen to this lecture about Abraham and what he means to the three great monotheistic faiths that hold him as important. Bruce Feiler, best-selling author of six books including Walking the Bible: A Journey by Land through the Five Books of Moses, delivers a lecture based on his book, Abraham: A Journey to the Heart of Three Faiths. Feiler talks about the meaning of Abraham in the Christian, Jewish and Muslim faiths and his personal quest to better understand this historical figure.

Jewish Ideas about Abraham

In Genesis 12: 1–3 Abraham (at that stage his name is still Abram) is called by God to:

‘Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you. I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you, and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing … and in you all the families of the earth shall be blessed’ (NRSV).

Because Abraham’s wife Sarai (later renamed Sarah) remains childless, Abraham has a son with Sarai’s slave Hagar. The child is called Ishmael. At this stage (Genesis 17) Abraham receives the commandment to circumcise all males when they are eight days old. At the same time he is told that Sarah will bear a son as well. This child of Sarah’s, when born, is named Isaac. Trouble brews between Sarah and Hagar as their sons grow up, and Sarah persuades Abraham to send Hagar and Ishmael away (Genesis 21). God promises Hagar that Ishmael, too, will be made into a great nation. God then tests Abraham’s faith by commanding him to sacrifice Isaac (Genesis 22). But when Abraham is about to sacrifice Isaac on Mount Moriah, an angel stops him and directs his gaze to a ram caught in the thicket. The ram is then sacrificed instead of Isaac.

In Jewish tradition the sacrifice of Isaac is called the Akedah, the Binding of Isaac. In times of persecution Jewish martyrs invoked the Akedah as they gave their lives in sanctification of God’s name (Kiddush ha-Shem).

In Jewish tradition Abraham became identified as the ‘first Jew’. He is depicted as the embodiment of the faithful Jew upholding God’s commandments. Traditionally Jews see themselves as the descendants of Abraham through his son Isaac and through Jacob, his grandson. In Jewish prayer-books God is referred to as the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob.

Christian ideas about Abraham

In Christian tradition Abraham’s faith became the example to follow for all those who sought to follow Jesus. In the words of Paul, in Romans 4:

‘For what does the scripture say? “Abraham believed God, and it was reckoned to him as righteousness.”

The purpose of this statement by Paul to the Romans was to make Abraham the ancestor of all who believe without being circumcised ( Abraham was eventually circumcised, but he believed in this one God before that actually happened) and who are then considered righteous. And of course Abraham is the ancestor of all circumcised Jews, as Abraham and his family were eventually circumcised according to the covenant. So Abraham became the spiritual father of all Christians, both those who came to Christian belief from Judaism and those who were Gentiles and began to follow Jesus without being circumcised. The Akedah, the Binding of Isaac on the altar, became the Sacrifice of Isaac in the Christian tradition. This story was understood as representing Jesus Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross in atonement for the sins of the whole of humankind. This is the way all families of the earth would be blessed through Abraham.

What is known about Abraham and Sarah?

The people considered matriarchs and patriarchs of the Bible are the three generations found in Genesis–Abraham and Sarah, their son Isaac and his wife Rebekah, and in the third generation the younger son of the twins, Jacob, and his wives Leah and Rachel. Stories about these three families are contained in Genesis chapters 12 through 50.

Scholarly opinion on the historicity of the stories concerning this group of people is seriously divided.

Some scholars will point to internal Biblical evidence for the authenticity and the antiquity of the patriarchal stories. These people, it is maintained by the position on the literal historicity of the Bible, were semi-nomads. They lived in tents. From time to time, they wandered off to Egypt or Mesopotamia, often in search of pasture for their animals. And various details of their language, their customs, their laws, their religion, seem to fit well into the period of the Late Bronze Age. The late Bronze Age dates from about 1550 BCE until 1200 BCE. This position holds that details in the Bible seem to indicate that these early Hebrews are real people who actually lived.

There are also scholars who see the patriarchal stories as entirely fabricated in a much later age, written to support Israel’s ambitions and claim to the land where they settled after being nomads. The scholars with this view vary significantly as to when they think these patriarchal stories were written: anywhere from the period of the Israeli monarchy all the way down to the fourth century BCE–during a period of about 600 years! They claim that the many inconsistencies and problems in the Biblical text concerning these matriarchs and patriarchs make it clear that these are important stories in much the same way that legends and myths are important stores–a way to make serious points about various ideas and beliefs, but that these are not literal history.

So there are these two extremes of scholarly opinion based on the internal evidence of the Bible itself.

There are these same two extreme positions reflected in the discipline of archaeology. In the early days of the field, archaeology of this region tended toward belief in the historical accuracy of the Biblical stories. Archeology in this region was explicitly referred to as Biblical Archaeology — an interesting name, because it suggests that the archaeologists were out there searching for evidence that would verify the details of the Biblical text.

Over time, many discrepancies between the archeological record and the Biblical text became apparent. Increasingly, practitioners of what is now being termed Palestinian Archaeology, or Ancient Near Eastern Archaeology, or Archaeology of the Levant, rather than Biblical Archaeology — some of these archaeologists grew disinterested in pointing out the correlations between the archaeological data and the Biblical stories or in trying to explain away any discrepancies in order to keep facts in line with what is found in the Biblical text. They began to focus on the best possible reconstruction of the history of the region on the basis of the archaeological evidence, regardless of whether or not those results would confirm the Biblical account of events. In fact, the archaeological reconstruction often contradicts Biblical claims. Clearly the Bible was not written to fit with the historical detail of its era. It had a different purpose.

Example: Biblical Archaeology Society

There is a great deal of archaeology happening in the Middle East, and in Israel alone the ability to do any kind of construction is often met with difficulties, as digging frequently turns up really vital historical materials! One resource of some very fine articles and information is Biblical Archaeology Society

You can find materials on all kinds of issues here, and there will be ways that the sites and issues discussed connect to various stories in the Bible. This is not a society that tries to prove anything about the Bible, however! It is about archaeology in lands that the Bible mentions, and what is actually found in those digs. Check it out!

It is a mistake to read the Bible as if it were written to be a historical record. The Bible is literature. Its composition is influenced and determined by literary and faith conventions and goals. In truth, there is no such thing as purely objective history–there is always some kind of slant to any version of any given event. Students and scholars have no direct access to any actual past events. They only mediate access in historic materials that are found and used. Even first person witness statements are from only one point of view. Archaeological remains are needed that yield information, but this information only comes after a process of interpretation. These Biblical texts are vital, but the texts are themselves are already an interpretation of events and thus must still be further interpreted by the reader.

Key Takeaway: what is the point of the Bible, anyhow?

So this discussion of the patriarchal stories is going to bear all of these considerations in mind. The assumption here will be that they are not historically accurate stories, but still of vital importance to those who wrote them.

And rid of the burden of historicity, the stories can be appreciated for what they are–powerful narratives that must be read against the literary conventions of their time, and whose truths are social, political, moral and existential.

So what are these truths? Answering this question comes from identifying some few of the major themes of Genesis 12 through 50.

Once again, here is the start of it all:

Genesis 13:1-3

“Now the Lord said to Abram, “Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you. 2 I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you, and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing. 3 I will bless those who bless you, and the one who curses you I will curse; and in you all the families of the earth shall be blessed. (NRSV)

Abram is commanded to go forth from his home and family to a location to be named later, a location that remains for now unspecified. And this is a fact that has caused commentators for centuries to praise Abram for his faith. Faith is a virtue that is connected or associated with Abram/Abraham in other Biblical contexts and also in later religious traditions.

He is seen as the paradigm, the exemplar of a man of faith. The command is coupled with a promise: “I will make of you,” God says, “a great nation, and I will bless you.”

And so the reader meets Abram, who has just been told that he is going to be the father of great nations– and Abram has a barren wife. He doesn’t seem to understand that the progeny he is promised by God is going to come from Sarai, and why should he think that it would? God wasn’t specific. God simply says, “I shall make of you a great nation.” God says nothing of Sarai, and after all– she’s barren. So Abram may be forgiven for thinking that perhaps some other mate awaits him. He willingly accepts Sarai’s offer of a handmaid, Hagar, to bear a child, Ishmael, for Abraham instead of Sarai doing so. The narrator shows Abram pinning his hopes on Ishmael as the child of the divine promise. But in Genesis 17 God finally, perhaps impatiently, indicates to Abram that he would father a great nation through Sarah from within his marriage. And Abraham, as he’s now called, is incredulous: “She’s past the age of bearing, Lord.” And with incredulity, Abraham laughs. And God is silent. Abraham asks for God’s favor to fall on Ishmael, but God is determined. The line will come through Sarah. One should perhaps not laugh at God.

Eventually Sarah bears a son– Isaac.

All of this drama through the first five chapters of the story are made possible by a seemingly irrelevant line in Genesis 11:30, a sort of throw-away datum in a family list that one might gloss over: “and Sarai was barren; she had no child.” And that’s the power and beauty of Biblical narrative.

A few verses later, when Abram and his wife Sarai and his nephew Lot and those traveling with them all reach Canaan, God makes an additional promise.

God says, “I will assign this land to your offspring.”

So in just a few short verses the writer has established the three-fold promise that underpins the Biblical drama that’s about to unfold: the promise of progeny, of blessing, and of land. That establishes a narrative tension for the stories of the patriarchs, but also for the story of the nation of Israel in subsequent books. In the patriarchal stories there is this suspense between the stories that threaten to extinguish God’s promises and the stories that reaffirm them. Israelite matriarchs seem to be a singularly infertile group. The lines of inheritance defy expectations: it doesn’t seem to go to the person that one might expect it to go to. The process by which the promise of land, inheritance, and a nation of believers is fulfilled is halting and torturous at times.

The Covenant with Abraham: Land, Descendants and Blessing

In Genesis 15, God’s promise to Abraham is formalized in a ritual ceremony. God and Abraham are said to “cut” a covenant — that is the verb that is used in making a covenant — and “covenant” is a central Biblical concept.

The Hebrew word for covenant is berit. It means vow, promise, even a contract, agreement or pact. Parallels to the Biblical covenant have been pointed out by many Ancient Near Eastern historians and scholars. In Ancient Near Eastern texts two main types of covenant exist: the suzerainty covenant and the parity covenant. A suzerainty covenant is a covenant in which a superior party, a suzerain, dictates the terms of a political treaty (usually), and an inferior party obeys them. The arrangement primarily serves the interest of the suzerain, and not the vassal or the subject. In a parity covenant, two equal parties both agree to observe the provisions of some kind of treaty.

There are four major covenants in the Hebrew Bible. They are initiated by Yahweh as expressions of divine favor and graciousness. Two of these covenants appear in Genesis. One is the covenant with Noah found in the expression of the rainbow; and the next covenant is the Abrahamic covenant. The Noahide covenant in Genesis 9:1-17 is universal in scope. It encompasses all life on earth. It stresses the sanctity of life and in this covenant, God promises never to destroy all life again.

By contrast, the Abrahamic covenant is a covenant with a single individual. The Bible moves from a covenant with all of humanity to a covenant with a single individual. And this covenant looks very much like an Ancient Near Eastern suzerainty covenant. God appears as a suzerain. God is making a land grant to a favored subject, which is very often how these types of covenants worked. There is then an ancient ritual that ratifies the oath. In general, in this kind of covenant, the parties to the oath would pass between the split carcass of a sacrificial animal as if to say that they agree they will suffer the same fate as this animal if they violate the covenant. In Genesis 15, Abraham cuts sacrificial animals in two and God, but only God, passes between the two halves.

The striking thing about the version of the Abrahamic covenant found in Genesis 15 is that only God seems to be obligated by the covenant, obligated to fulfill the promise that was made. Abraham doesn’t appear to have any obligation in return. And so in this case, it is the subject, Abraham, and not the suzerain, God, who is benefited by this covenant, and that is a complete reversal of expectations. The Biblical writer goes out of his way to provide a moral justification for this grant of land to Israel. In the Biblical writer’s view, God is the owner of the land, and so is empowered to set conditions or residency requirements for those who would reside in it, like a landlord. The current inhabitants of the land are polluting it, filling it with bloodshed and idolatry. When the land becomes this polluted it will spew out its inhabitants. That process, God says, isn’t complete; so Israel is going to have to wait a little while before inhabiting their land. God says in Genesis 15:16 that the iniquity of the Amorites will not be fulfilled until later, and then when the Amorites are evil enough, Israel will gain the land in place of that people, who will lose it. So here, and in other places in the Bible, it is clear that God’s covenant with Israel is not due to any special merit of the Israelites or favoritism: this is actually said explicitly in Deuteronomy. Rather, God is seeking replacement tenants who are going to follow the moral rules of residency in this land. The Amorites are evicted, the Israelites given a chance.

Genesis 17 seems to be a second version of the same Abrahamic covenant. This time, scholars attribute the writing of this version to the P source — the Priestly writer. There are some notable differences in this version of the covenant, emphasizing themes that were important to the Priestly writer. God adds to the promises in Genesis 17 that a line of kings will come forth from Abraham, and then, that Abraham and his male descendants be circumcised as a perpetual sign of the covenant.

There is actually some obligation for Abraham in this second version of this covenant.

Gen 17:13-

“Thus shall my covenant be marked in your flesh as an everlasting pact”

Failure to circumcise is tantamount to breaking the covenant, according to this text.

Circumcision is known in many of the cultures of the Ancient Near East. It was generally a rite of passage that was performed at the time of puberty rather than a ritual that was performed at birth, or eight days after birth. But as is the case with so many Biblical rituals or institutions or laws, whatever their original meaning or significance in the ancient world, whether this was originally a puberty rite or a fertility rite of some kind, the ritual has been suffused with a new meaning in the Hebrew texts. So circumcision here is infused with a new meaning: it becomes a sign of God’s eternal covenant with Abraham and his seed.

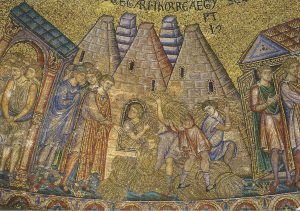

The Story of Abraham and Isaac

The greatest threat to the promise of land, blessing and many descendants actually comes from God, and that threat happens in Genesis 22, when God tests Abraham with the most horrible of demands. The child of the promise, Isaac, who was born miraculously to Sarah when she was no longer of child-bearing age, is to be sacrificed to God by Abraham’s own hand. And the story of the binding of Isaac is one of the most powerful, most riveting stories not only in the Bible but, some have claimed, in all of world literature.

The Story: The Binding of Isaac from the British Library

The story is a marvelous example of the Biblical narrator’s literary skill and artistry. Looking at the story from the Jewish perspective might be useful. Professor and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel is a natural story teller and interpreter.

Activity: Elie Wiesel on the Akedah

The Biblical narrator’s concealing of details and the motives of the three main characters, God, Abraham, and Isaac, leads to real ambiguity in this story, and the possibility of many differing interpretations of it. Why is God testing Abraham? Does God really desire such a sacrifice? What is Abraham thinking and feeling as he walks — for three days — walks with his son, bearing the wood and the fire for the sacrifice? Does he fully intend to obey this command, to annul the covenantal promise with his own hand? Or does he trust in God to intervene? Or is this a paradox of faith? Does Abraham intend faithfully to obey, all the while trusting faithfully that God’s promise will nevertheless be fulfilled? What is Isaac thinking? Does he understand what is happening? How old is he? Is this a little boy or a grown man? Is he prepared to obey? He sees the wood and the firestone in his father’s hand. Clearly a sacrifice is planned. He’s got three days to figure that out. He asks his father: Where is the sheep for the burnt offering? Does he know the answer even as he asks? Does he hear the double entendre in his father’s very simple and solemn reply, which in the unpunctuated Hebrew might be read, “The lord will provide the sheep for the offering: my son.” Does Isaac struggle when he’s bound? Does he acquiesce to being the sacrifice?

The beauty of the narrative is its sheer economy. It offers so little that readers are forced to imagine the innumerable possibilities. The drama plays out in countless ways, with an Abraham who is reluctant and an Isaac who is ignorant. Or an Abraham who is eager to serve his God to the point of sacrificing his own son, and an Isaac who willingly bares his neck to the knife.

But of course the story can be contextualized in a number of different ways. For example, one can read the story in its historical context of child sacrifice in the Ancient Near East. Although child sacrifice was adamantly condemned in various later layers of the Bible, there is plenty of evidence that it was probably practiced in different quarters throughout the period of the Israelite monarchy. Does Genesis 22 assume or reject the practice of child sacrifice? Some scholars argue that a core story promoting child sacrifice has been edited so as to serve as a polemic against child sacrifice now in its final form. Can a reader see the seams and feel the narrative tensions that would support such a claim? Does the story pull in more than one direction?

Or one can read the story in its immediate literary context. Abraham has just permitted the expulsion of Ishmael, the only beloved son of Hagar. And now God demands that he sacrifice his beloved son Isaac. What might God be trying to teach Abraham? Is this a trial in the sense of a test or a trial in the sense of a punishment? The Hebrew term for this sacrifice as a “trial” can encompass both meanings.

Can this be the same Abraham who a few chapters after arguing with God to not destroy all of Sodom and Gomorrah, when told to slaughter his only son, his perfectly innocent and presumably deeply loved son, not only makes no objection, but rises early in the morning to get started on the long journey to the sacrificial site? What are we to make of the juxtaposition of these two stories? Which represents behavior more desirable to God?

How does this covenant come to be when it is perpetually challenged by the God who initiated it? It is a big question while looking at the book of Genesis, but in particular, at the story of Abraham.

Isaac and Jacob

Isaac, who is the child of God’s promise to Abraham, is often described as the most invisible of the patriarchs or the most passive of the patriarchs. Perhaps his passive acceptance of his father’s effort to sacrifice him serves as the key to the Biblical narrator’s perception of his character. By contrast, his wife Rebekah is often described as the most determined and energetic of the matriarchs, proactive all through her life in taking hold of the direction her life might take. Rebekah herself personally accepts the offer of an unknown bridegroom in a far away land and overrides the urgings of her mother and her brother to delay her departure. “No”, she says, “I’m ready to go. I’ll go now.” In Genesis 24:67 it says that Isaac brought Rebekah “into the tent of his mother Sarah, and he took Rebekah as his wife. Isaac loved her and thus found comfort after his mother’s death.”

But like the other matriarchs, Rebekah is barren. So Isaac pleads with God for a child on her behalf. And Rebekah becomes pregnant with twins. The older child is Esau — Esau will be the father of the Edomites — and the younger is Jacob, who will be the father of the Israelites. Now, Jacob is the most fully developed, the most colorful and the most complex of the patriarchs. Jacob has long been identified by commentators as the classic trickster, a type known from folklore. Jacob tricks his brother out of his birthright, and in turn is tricked by his brother-in-law, his wife and later his own sons. How much of Jacob’s trickery is really necessary? After all, Rebekah, who suffers tremendous pain during her pregnancy, is told by God that the twins who are fighting and struggling for priority in her womb will become two nations, the older of which will serve the younger. That happens in Genesis 25:23.

“Two nations are in your womb; two separate peoples shall issue from your body; one people shall be mightier than the other; and the older shall serve the younger.”

And indeed, the real life nations of Israel and Edom were long-time enemies — Esau is the father of the Edomites according to the Biblical texts — and for a time, Edom was subjugated by Israel, according to the Biblical texts, under King David.

Learning materials: Lecture by Professor Daniel J Elazar[3]

A little more in depth information about Esau and Jacob, and what emerged from both of these brothers according to Jewish studies and Biblical detail:

Some scholars have argued that this announcement that the older shall serve the younger is the narrator’s way of establishing for the reader that the younger child, Jacob, is the son who will inherit the divine blessing. That then raises serious questions about Rebekah and her son Jacob’s morally dubious efforts to wrest the blessing and birthright from Esau. Are they are fulfilling a divine plan? Is it alright to fulfill a divine plan by any means, fair or foul? Or is it to be understood that Jacob’s possession of the birthright was predetermined, disengaged from all of his acts of trickery? He and Rebekah plot to deceive Isaac in his rather shaky old age into bestowing the blessing of the firstborn on Jacob instead of Esau. So perhaps by informing the reader that Jacob had been chosen from the womb, the narrator is able to paint a portrait of Jacob at this stage in his life as grasping and faithless: a great contrast to his grandfather, Abraham.

Jacob’s poor treatment of his twin brother, Esau, earns him Esau’s enmity and because of this, Jacob finds it expedient to leave Canaan and remain at the home of his mother’s brother, Laban. On his way east, back to Mesopotamia from Canaan, Jacob has an encounter with God. At a place called Luz, Jacob lies down to sleep, resting his head on a stone. While sleeping, he has a dream in which he sees a ladder. The ladder’s feet are on the earth, it reaches to heaven and there are angels ascending and descending on the ladder. In the dream God appears to Jacob and reaffirms the Abrahamic or patriarchal covenant. God promises land, posterity and in addition, Jacob’s own safety, his own personal safety until he returns to the land of Israel. Jacob is stunned.

In Genesis 28:16-17:

“Then Jacob woke from his sleep and said, “Surely the Lord is in this place—and I did not know it!” 17 And he was afraid, and said, “How awesome is this place! This is none other than the house of God, and this is the gate of heaven.” (NRSV)

The stone that served as Jacob’s pillow he then sets up as a cultic pillar, a memorial stone. He sanctifies the stone with oil and he renames the site Bethel, Beyt El, which means “the house of God”.

But it is significant that despite this direct vision, Jacob, so unlike Abraham in personality, is still reluctant to rely on God and his promise. And so Jacob makes a conditional vow.

Genesis 28:20-22:

20 Then Jacob made a vow, saying, “If God will be with me, and will keep me in this way that I go, and will give me bread to eat and clothing to wear, 21 so that I come again to my father’s house in peace, then the Lord shall be my God, 22 and this stone, which I have set up for a pillar, shall be God’s house; and of all that you give me I will surely give one-tenth to you.” (NRSV)

So where once God had tested Abraham, it seems now that Jacob is almost testing God. “If you can do all this for me, then fine, you can be my God” seems to be what Jacob says at this point.

Jacob spends 14 years in the household of his uncle, his mother’s brother, Laban. Jacob meets Laban’s two daughters: Leah the elder daughter and Rachel the younger. And he soon loves Rachel. He agrees to serve Laban for seven years for the hand of the younger daughter Rachel. When the seven years pass, Laban deceives Jacob and gives him the elder daughter, Leah. Jacob, the trickster, is furious at having been tricked himself, and in much the same way — using an older and a younger sibling, one disguised as the other, wearing the covering of the other, just as he tricked his own father. But he is willing to give seven years more service for Rachel. In this multiple marriage, Rachel, Leah, and their two handmaidens will conceive and give birth to one daughter and 12 sons, from whom will come the 12 tribes of Israel. But it is the two sons of his beloved Rachel, Joseph and Benjamin, who are the most beloved to Jacob.

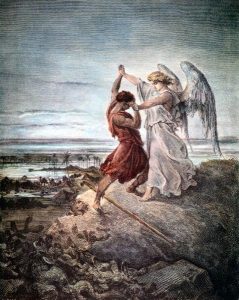

Jacob determines finally to leave Laban and return to Canaan. There’s one final remarkable incident in Jacob’s life that occurs on his return journey. It is an incident that most readers associate with a significant transformation in his character. The event is Jacob’s nighttime struggle with a mysterious figure, who in some way is a representative of God. This struggle occurs as Jacob is about to cross the river Jabbok and reconcile himself with his former rival and enemy, his brother Esau.

The story begins like this–Jacob has sent everyone on ahead: his wives, his children, his household, his possessions.

Jacob is then standing alone at the river. Genesis 32:24-31 says.:

24 Jacob was left alone; and a man wrestled with him until daybreak. 25 When the man saw that he did not prevail against Jacob, he struck him on the hip socket; and Jacob’s hip was put out of joint as he wrestled with him. 26 Then he said, “Let me go, for the day is breaking.” But Jacob said, “I will not let you go, unless you bless me.” 27 So he said to him, “What is your name?” And he said, “Jacob.” 28 Then the man said, “You shall no longer be called Jacob, but Israel, for you have striven with God and with humans, and have prevailed.” 29 Then Jacob asked him, “Please tell me your name.” But he said, “Why is it that you ask my name?” And there he blessed him. 30 So Jacob called the place Peniel, saying, “For I have seen God face to face, and yet my life is preserved.”

31 The sun rose upon him as he passed Peniel, limping because of his hip. (NRSV)

Many scholars see this story as an Israelite adaptation of popular stories of river gods who threaten those who wish to cross a river, or trolls or ogres who guard rivers and have to be defeated by a hero, making the river safe to cross. In its Israelite version, however, this story is historicized. It is associated with one particular character at a historical time and it serves to explain why the Israelites abstained from eating the sciatic nerve of an animal even to this day. The reader also learns how Peniel gets its name and how Israel gets his name, as well.

Names are an important theme of this story. In the Biblical context, names encapsulate the essence of their bearer. Naming something or knowing the name of something gives one control or power over that thing. And that is why the stranger who wrestled with Jacob will not reveal his name to Jacob. It would give Jacob power over him.

Jacob’s own name is the occasion for some punning in this story. His name is built on this root Y.’.Q.B: Ya-‘a-qov –It means to supplant or uproot. He emerges from the womb grasping his brother’s heel. ‘aqev , which is the word for “heel,” is based on that root.

Jacob’s very name hints at and foreshadows the struggling, the wrestling, the trickery that are the major themes of his life. But his striving has reached a climax here. And so the angel names him Yisra’el, Israel, which means he who has striven with God. Because as the stranger says, he has striven and wrestled all his life with men, particularly his brother, and now he struggled with God. El means god, the name of the chief god of the pantheon of Canaan. So he is called Yisra’el, “he who has struggled with God”.

And although Jacob appears to be something of an anti-hero — he actually literally limps into the Promised Land alone — Jacob is now a new and honest man. This is obvious in his reunion with Esau. He greets his former rival and enemy with these words in Genesis 33:10-11:

“ ‘If you would do me this favor, accept from me this gift, for to see your face is like seeing the face of God, and you have received me favorably. Please accept my present, which has been brought to you, for God has favored me, and I have plenty.’ And when he urged him, he accepted.”

Many commentators have observed that the change in name from Jacob to Israel accompanies a change in character, a change of essence in Israel. So some have noted that the struggle with the angel is the final purging of the unsavory qualities of character that marked Jacob’s past career.

With Jacob, who is now Israel, God seems finally to have found the working relationship with humans that God has been seeking since their creation. God learned immediately after creating this unique being that the humans will exercise their free will against God. God saw that it was important to limit the life span of humans, or risk having an entity in humanity that was nearly equal to God. So God casts the humans out of the Garden and blocks their access to the tree of life. But humans continue their violent and evil ways, and in desperation, God wipes them out, and starts again.

This second creation of humans, post-Noah, proves to be not much better than the first set. They forget God, they turn to idolatry. God has promised at this point, however, not to destroy all humankind again, and so experiments with a single individual of faith. Abraham’s faith withstands many trials. He is obedient to God in a way that no one has been up to this point in the narrative, but perhaps in Abraham’s stories the model of blind obedience is rejected, too. When Abraham prepares to slaughter his own son, perhaps God sees that blind faith can be as destructive and evil as disobedience, so God relinquishes the demand for blind obedience: God actually stops Abraham from blind obedience in the story.

The only relationship that will work with humans comes to be one in which there is a balance between unchecked independence and blind obedience, and God seems to find that relationship with Jacob. And the metaphor for that relationship is a metaphor of struggle, or wrestling. Remember Yisrael means “one who wrestles, who struggles with God.” God and humans lock in an eternal struggle, neither prevailing, yet both forever changed by their encounter with one another.

The 12 Sons of Jacob: Joseph and His Brothers

Now the rest of Genesis relates the story of Joseph and his brothers, the 12 sons of Jacob. It is one of the most magnificent psychological dramas in the Bible. The story is intensely human. It focuses very much on the family relationships, on the jealousies among brothers.

Scholars are divided over the authenticity of the Egyptian elements in the story. Radically diverse things are read in this story. Some point to the presence of Egyptian names, customs, religious beliefs, and laws as a sign of some historical memory being preserved in these stories. Others point to all the problems, the anachronisms, and the general lack of specificity as a sign that this story is composed quite late. The art of dream interpretation plays a very important role in this story, and dream interpretation was a developed science, particularly in Egypt and the other parts of Mesopotamia. So is it an Egyptian story?

Joseph’s brothers are jealous of Jacob’s partiality to Joseph, and so they conspire to be rid of him. But at the last moment, his brother Judah convinces the brothers that, if instead of killing him, they sell him, they can profit a little for their troubles. So Joseph is sold into slavery and eventually ends up in the household of Pharaoh in Egypt.

Joseph is known for his ability to interpret dreams, but the Biblical narrator is very concerned to describe him as reporting what God reveals to him about dreams, rather than relying on some kind of occult science of dream interpretation. Joseph rises to a position of great power when he correctly interprets some dreams regarding an impending famine in Egypt, and with Joseph as the governor of the country, in control of the grain supply, Egypt successfully weathers seven years of famine.

This famine, which strikes Canaan as well, drives Joseph’s brothers to Egypt in search of food, and Joseph doesn’t initially reveal himself to his brothers. He puts them to the test. He wants to know if they are the same men who so callously broke their father’s heart by selling Joseph, his father’s favorite, so many years ago. In the climatic moment in the story, Joseph demands that his frightened brothers leave Benjamin — the other son of Rachel, the other son of the most beloved wife — as a pledge in Egypt.

Joseph knows that it would decimate his father Jacob to lose Rachel’s only remaining son, but he is testing his brothers to see whether they have reformed since the day that they sold him into slavery. And indeed Judah, the one who had figured so prominently in the sale of Joseph, that had crushed his father, Judah steps forward and offers himself instead of Benjamin. He says: It would kill my father now to lose Benjamin, the last son of his beloved wife, Rachel. So the brothers, having proven their new integrity, are allowed to see Joseph for who he really is. Joseph reveals his identity in a very moving scene, and ultimately the whole family is relocated to Egypt, where they live peacefully and prosperously for some generations.

That is the basic outline of the story of Joseph and his brothers, but one of the important themes of these stories is the theme of God’s providence. The writer in Genesis wants to represent Jacob’s sons, their petty jealousies, their murderous conspiracy, Joseph himself, all as the unwitting instruments of a larger divine plan. In fact, Joseph says to his brothers in Genesis 50:20,

“As for you, you meant evil against me, but God meant it for good, to bring it about that many people should be kept alive as they are today.”

Joseph’s betrayal by his brothers set the stage, not only for the reformation of his brothers’ characters, which is an important part of the story, but for the descent of all of the Israelites into Egypt, so as to survive widespread famine. So yet another threat to the promises in the Covenant is overcome: threat of famine is overcome by the relocation to Egypt.

Significantly, God says to Jacob in Genesis 46:4,

“ I myself will go down with you to Egypt, and I will also bring you up again.”

Israel’s move to Egypt sets the stage for the rise of a pharaoh who, the text says, did not know Joseph and all that he had done for Egypt. And this new pharaoh then enslaves the Israelites, and so vigorously embitters their lives that their cry will rise up to heaven in protest. And thus begins the book of Exodus, which will show the journey from Egypt to Sinai and finally to the shores of the Jordan River.

Most of the narrative account in Genesis 12 to 50 is assigned by scholars to the J source, and certain themes emerge in the J narrative. The first is that while God’s promise is sure, the manner and the timing of its fulfillment is quite unpredictable. The land never belongs to the patriarchs to whom it was promised, and it is already inhabited. The Hebrew people will take possession of it, but according to the story, this only happens after a tremendous struggle. God doesn’t remove the residents from the land–the Israelites will have to do it themselves.

In other ways God’s methods of creating a nation are curious. Why does God go against the traditional Ancient Near Eastern practice of primogeniture, inheritance by the first born? God chooses Jacob, a liar and a cheat in his early life, over the elder Esau. Why does God then choose young Joseph, who is an arrogant, spoiled brat? Joseph provokes his brothers with his delusions of grandeur. Compare the law of primogeniture that’s listed in Deuteronomy 21:15-17:

“If a man has two wives, one loved, and the other unloved, and both the loved and the unloved have borne him sons, but the first-born is the son of the unloved one — / when he wills his property to his sons, he may not treat as first-born the son of the loved one in disregard of the son of the unloved one who is older.”

And yet isn’t this what happens to Ishmael? Isn’t this what happens to Esau? Isn’t this what happens to all of Joseph’s brothers who are born before him? And there is no explanation about all of this in the Biblical text.

Yet despite the false starts, and the trials, and the years of famine, and the childlessness, and the infertility, the seed of Abraham survives, and the Covenant promise is reiterated:

“I myself will go down with you to Egypt, and I will also bring you back again.”

So ultimately, the J source would appear to assert God does control history, that all of this tends towards God’s purpose in establishing the Hebrew people in a land to be given to them.

Christine Hayes, Introduction to the Old Testament, Yale University: Open Yale Courses, http://oyc.yale.edu (April 2022). License: Creative Commons BY-NC-SA Some materials here used from Yale University, copyright 2007 Some rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated on this document or on the Open Yale Courses web site, all content is licensed under a Creative Commons License (Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0).

British Library Sacred Texts: Judaism, Sept. 2019, https://www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/videos/judaism.

May, Herbert G., et al. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha: Revised Standard Version, Containing the Second Edition of the New Testament and an Expanded Edition of the Apocrypha. Edited by Michael D Coogan, Oxford University Press, 2007.

Gabel, John B. The Bible as Literature: An Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2006.

Elazar, Daniel. “Jacob and Esau and the Emergence of the Jewish People.” Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, https://www.jcpa.org/dje/articles/jacob-esau.htm.

Wiesel, Elie. Elie Wiesel: The Akedah: Exploring Uncertainty … – Youtube. 9nd St Y Elie Wiesel Archive, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BV-pvpmcACw.

“Bruce Feiler: A Journey to the Heart of Three Faiths – .” University of California Television, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sEFi-KzVRd8.

- Anna Sapir Abulafia is Professor of the Study of the Abrahamic Religions at the Faculty of Theology and Religion at the University of Oxford and a Fellow of Lady Margaret Hall. She has published widely on medieval Christian-Jewish relations. At present she is engaged in a project examining the place of Jews and Muslims in Gratian’s Decretum. ↵

- Christine Hayes is the Robert F. and Patricia Ross Weis Professor of Religious Studies at Yale. She received her Ph.D. from University of California, Berkeley in 1993. A specialist in talmudic-midrashic studies, Hayes offers courses on the literature and history of the biblical and talmudic periods. She is the author of two scholarly books:Between the Babylonian and Palestinian Talmuds, recipient of the 1997 Salo Baron prize for a first book in Jewish thought and literature, and Intermarriage and Conversion from the Bible to the Talmud, a 2003 National Jewish Book Award finalist. She has also authored an undergraduate textbook and several journal articles. ↵

- Daniel Elazar was Professor of Political Science at Temple University in Philadelphia, where he founded and directed the Center for the Study of Federalism, a leading federalism research institute. He held the Senator N.M. Paterson Professorship in Intergovernmental Relations at Bar-Ilan University in Israel, heading its Institute for Local Government. In 1986, President Reagan appointed him a citizen member of the U.S. Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations, the major intergovernmental agency dealing with problems of federalism. He was appointed for a second term in 1988 and a third in 1991. He was the founding president of the International Association of Centers for Federal Studies, was Chairman of the Israel Political Science Association, Secretary of the American Political Science Association, and was a member of various consultative bodies of the Israeli government. Professor Elazar was the author or editor of more than 60 books and many other publications including a 4-volume study of the Covenant Tradition in Politics, as well as Community and Polity, The Jewish Polity, and People and Polity, a trilogy on Jewish political and community organization from earliest times to the present. He also founded and edited the scholarly journal Jewish Political Studies Review. His books in the area of federalism include The American Partnership; American Federalism, A View from the States; The American Mosaic; Cities of the Prairie and Cities of the Prairie Revisited; and Exploring Federalism. He was also the founder and editor of Publius, the Journal of Federalism. ↵

a procedure for males in which the foreskin of the penis is removed. This is a religious ritual in Islam and Judaism, and can be used medically in some situations or cultures

a sovereign or state having some control over another state that is internally autonomous. a feudal overlord