6 Genesis: Human origins

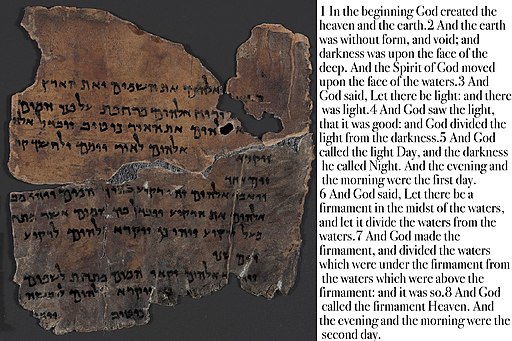

Creation of Humanity: Genesis 1-3

There are two creation stories in the beginning of Genesis. Genesis 1:1 through Genesis 2:4 is the first account, set in a poetic format. The Biblical God in this version is presented as being supreme and unlimited. The second story, in Genesis 2:4 through Genesis 3, is a narrative, an actual story. The God here seems to be approachable, a being with whom the humans newly created can have a relationship.

Sometimes these early Biblical creation stories are referred to as myths. But they are not a part of a mythology. So we need to differentiate between the concepts of mythology and myth.

- The term Mythology is used to describe stories that deal with the birth and the the life events of various gods and demi-gods, sometimes even including legendary heroes, but the mythology is narrating a sequence of events about these characters. The Biblical creation account is non-mythological because there is no biography or life story of the Biblical God in here. In Genesis, God simply is. There’s no account of God’s birth or any lifetime activities of the divine being.

- But this pair of creation accounts are stories that are myths. Myth is a term used to refer to a traditional story that is fanciful and is designed to explain the existence of either a thing or a practice or even a belief. Sometimes a myth is a story that’s a veiled explanation of a truth. Sometimes a myth is making a point, and doesn’t expect the listener or reader to actually believe the events in the story happened, but that they will understand the bigger point of the story. Think of Aesop’s Fables, making moral points by using animals with personalities. Think of Aslan in the Narnia series, standing in for the concept of God. Even fairy tales often had a warning, a bigger point to make than just a fanciful story.

Comment: about myths

From Oxford Bibliographies:

” Persons who hold that the Bible has been infallibly revealed by God and those who consider myth as something untrue may well find it offensive to posit that myth is present in the Bible. By contrast, those who see myth as one of the ways that a traditional society expresses it most profound truths may find inspiration in seeing Biblical narratives as myth.”

The Bible doesn’t have a full-blown mythology. It doesn’t focus on stories about the lives and deaths and interactions of a whole pantheon of gods, or even any kind of life story of the one God identified in Genesis, but the Bible does certainly contain myths. Genesis is full of traditional stories and legends, some quite fanciful, which explain how and why some things are the way they are. There is no sense from the stories and myths in the Bible, however, that God is somehow tied to any particular natural substance or phenomena. This divine being is not the Sun God or the Ocean God. The one God as presented in the Bible is separate, above, and transcendent to nature. The Biblical God’s powers and knowledge do not appear to be limited by the prior existence of any other substance or power. Nature does not have a divine element or being in the Bible.

Story One

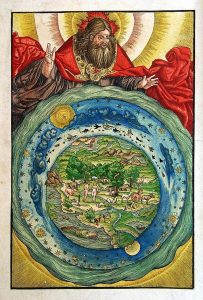

In Genesis 1, the view of God is that there is one supreme god, who is creator and sovereign of the world, who simply exists, who appears to be incorporeal, and for whom the realm of nature is separate and subservient. God has no life story, no mythology, and God’s will is absolute.

Example: Creation Stories

In Genesis, creation takes place through the simple expression of God’s will. “When God began to create heaven and earth,” and there’s a parenthetical clause: “God said, ‘Let there be light’ and there was light.” God expressed the will that there would be light, and there was light

That is a very different approach from many Ancient Near Eastern stories in which there’s always a sexual principal at work in creation. In many of the stories from the same period, or even from an earlier time than the writing of Genesis, the act of creation is always the result of procreation in some way, male and female principles combining. There’s an Egyptian creation story in which the god Ptah just wills “let this be.” It reads very much like Genesis 1 and yet even so there’s still a sexual act that follows the expression of those wills, so it is still very distinct from the approach seen in the Genesis narrative.

In the Genesis creation stories humans are important. The two accounts are extremely different but they both signal the unique position and dignity of the human being.

In the first account in Genesis 1 the creation of the human is clearly the climactic divine act: after this last piece of creation, God can rest. And a sign of the humans’ importance is the fact that humans are said to be created in the image of God, which occurs in Genesis 1:26,

Then God said, “Let us make humankind[1] in our image, according to our likeness.”

Looking at the continuation of the passage it is clear that humans are going to be charged with specific duties towards, and rights over, the created world. It seems that the idea of being created in the image of God is then connected to those special rights and duties. A creature is required to take care of the creation, and it has to be a creature who is distinguished in certain ways from all the other animals. How are humans distinguished from other animals? It might include characteristics like the capacity for language and higher thought or abstract thought, conscience, self-control, and free will.

If those are the characteristics (such as capacity for language and higher thought or abstract thought, conscience, self-control, and free will) that earn human beings certain rights over creation but also give them duties towards creation, and the human is distinct from animals in being created in the image of God, there’s perhaps a connection:

—-to be godlike is to perhaps possess some of those characteristics.

The concept of the divine image in humans is a powerful idea, and that idea breaks with other ancient conceptions of the human.

In Genesis 1, humans in Genesis are not presented as the helpless victims of blind forces of nature. They’re not the menials and servants of capricious gods. They are creatures of majesty and dignity and they are of importance to, and objects of concern for, the God who has created them. At the same time humans are not themselves, however, gods. They are still creatures in the sense that they are created things and are dependent on a higher power.

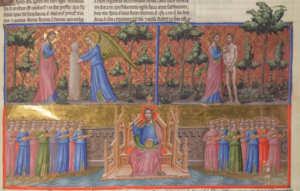

Story Two

In the second creation story, beginning in Genesis 2:4, the first human is formed when God fashions it from the dust of the earth, or from clay. There are many Ancient Near Eastern stories of gods fashioning humans from clay; there are depictions of gods as potters at a potter’s wheel just turning out little humans. But the Biblical account, as much as it borrows from that potter motif, takes pains to distinguish and elevate the human. Significantly, this God blows the breath of life into Adam’s nostrils. So God fashions this clay figure, and then breathes life, God’s own life, into it.

This idea that the human being is a mixture of clay, molded from clay but enlivened by the breath of God, captures that paradoxical mix of earthly and divine elements, dependence and freedom that marks the human as unique.

It should further be noted that in both creation accounts, man and woman are in an equal relationship before God. The Hebrew word that designates the creature created by God is the word adam. It is actually not a proper name; it is adam, it is a generic term. It simply means human or more precisely earthling because it comes from the word adamah, which means ground or earth. So this is adam, an earthling, a thing that has been taken from the earth.

Genesis 1 states that God created the adam, with the definite article: this is not a proper name. God created the adam, the earthling, “male and female God created them.” Moreover, this earthling that seems to include both male and female, is then said to be in the image of God. That suggests that the ancient Israelites didn’t conceive of God as necessarily gendered. The adam, the earthling, male and female, was made in the image of God.

In the Genesis 2 creation account, it’s not clear that the woman is subordinate to the man. Many medieval Jewish commentators enjoy pointing out that she was not made from his head so that she not rule over him, but she wasn’t made from his foot so that she would be subservient to him; she was made from his side so that she would be a companion to him. In this second account of creation, the creation of woman is in fact the climactic creative act in the second Genesis account. With her formation, creation is now complete.

The second creation account also shows the relationship between humans and the rest of creation quite clearly. Humans are going to be caretakers, stewards, and they will find everything that they need in the creation to live well. They simply must be responsible for the creation.

What else is happening in Biblical Creation?

So the Biblical creation stories, individually and jointly, present a portrait of the human as the pinnacle and purpose of creation: godlike in some way, in possession of distinctive faculties and characteristics, that equip them for stewardship over the world that God has created.

Finally, consider the image of the world that emerges from the creation story in Genesis. In these stories, there’s a very strong emphasis on the essential goodness of the world. After each act of creation what does God say? “It is good.” Genesis 1 verse 4, verse 10, verse 12, verse 18, verse 21, verse 25… and after the creation of living things, the text states that God found all the work to be very good. There are seven occurrences of the word “good” in Genesis 1. That is something to watch for. If a passage in the Bible shows a word coming up a lot, count the occurrences of that words. There might be either seven or ten occurrences in total. The sevenfold or the tenfold repetition of a word is called a leitwort, a recurring word that becomes thematic. That’s a favorite literary technique of various Biblical authors.

In reading Genesis 1 there is this recurring phrase — “and it was good… and God looked and it was good… and God looked and it was good”. The world is good; humans are important; they have purpose and dignity.

The Biblical writer is rejecting the concept of a primordial evil, a concept found in the literature of the Ancient Near East. For the Biblical writer of this story, it would seem that evil is not a metaphysical reality built into the structure of the universe. Evil is not created in these stories.

The first chapter of Genesis begins with a temporal clause which is unfortunately often translated “In the beginning,” which implies that what follows is an ultimate account of the origins of the universe. That translation causes people to believe that the story is giving an account of the first event in time; but it is actually a fairly bad translation. The Hebrew phrase that starts the book of Genesis is better translated: “When God began creating the heavens and the earth… God said, ‘Let there be light and there was light.’”

And that translation suggests that the story isn’t concerned to depict the ultimate origins of the universe. It’s interested in explaining how and why the world got the way it is. When God began this process of creating the heaven and the earth, and the earth was unformed and void, and God's wind was on the surface of the deep and so on, God said, “Let there be light and there was light.”

In the beginning, according to Genesis, something exists but it has no shape. So the creation in Genesis 1 is not described as a process of making something out of nothing: that’s a notion referred to as creation ex nihilo, creation of something out of utter nothing. Creation instead is a process of organizing pre-existing materials and imposing order on those chaotic materials. So it begins with this chaotic mass and then there’s the ruah of God. Sometimes this word “ruah” is translated as “spirit” but it really doesn’t mean that alone in the Hebrew Bible. Ruah most often means "wind". So: “when God began to create heaven and earth — the earth being unformed and void,” the wind of God comes sweeping over the deep. There is wind, There is a primeval chaotic, watery mass or deep, the wind of God, and then surprise, there’s no battle between any forces at all-- there’s just the words, “let there be light.”

And the Ancient Near Eastern listener would prick up their ears: where’s the battle, where’s the violence, where’s the gore? Something new, something different was being communicated in this story. And don’t think the Biblical writers didn’t know this motif of creation following upon a huge cosmic battle, particularly a battle with a watery, dragon-like monster.

There are many poetic passages and poetic sections of the Bible that contain very clear and explicit references to that creation myth containing a battle and lots of monsters. It was certainly a story known and told to Israelite children and was a part of the Israelite culture. It is mentioned in Job; it is mentioned in Psalm 74:12-17:

“O God, my king from of old, who brings deliverance throughout the land;/it was You who drove back the sea with Your might, who smashed the heads of the monsters in the waters;/it was You who crushed the heads of Leviathan.”

Other passages contain similar lines. In Isaiah 51:9-10 it says: “It was you that hacked Rahab” — this is another name of a primeval water monster — “in pieces,/[It was you] That pierced the Dragon./It was you that dried up the Sea,/The waters of the great deep.”

These battle stories with mythic danger and evil were familiar stories to the people of the region and of that time, the stories were known in Israel, they were even recounted in Israel. They were stories of a god who violently slays the forces of chaos, represented as watery dragons, as a prelude to creation.

The rejection of this idea of the divine slaying the evil forces of chaos in Genesis 1 is pointed and purposeful.

It is a demythologization of creation.

Genesis is a removal of the creation account from the realm and the world of mythology. It is a pointed and purposeful change of narrative. It wants people to conceive of God as an uncontested god who through the power of a simple word creates the cosmos.

Now the story of creation in Genesis 1 takes place over seven days, and there’s a certain logic and parallelism to the six days of creating. It is expressly stated by God that humans are to be given every fruit bearing tree and seed bearing plant, fruits and grains for food. That is what it says in Genesis 1:29. That is what the humans are going to eat. There’s no mention of chicken or beef, there’s no mention made of killing animals for food. In Genesis 1:30, God says that the animals are being given the green plants, the grass and herbs, for food. In other words, there should be no competition for food. Humans have fruit and grain-bearing vegetation, animals have the herbage and the grasses. There is no excuse to live in anything but a peaceful co-existence.

Therefore, humans, according to Genesis 1, were created vegetarian, and in every respect, the original creation is imagined as free of bloodshed and violence of every kind. “And God saw… that it was very good.”

So Israelite accounts of creation contain clear allusions to and resonances of Ancient Near Eastern creation stories, but perhaps Genesis 1 can best be described as demythologizing of what was a common cultural heritage. Genesis 1 makes it clear in its story that evil is not represented as a physical reality. Evil is not built into the structure of the world. When God rests and looks at the whole thing, it’s very good, the whole thing is set up very well.

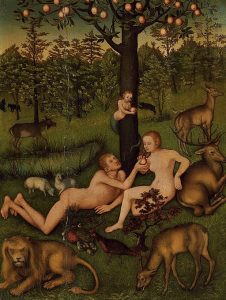

But there is Evil...

And yet the Hebrew people believe that evil is a condition of human existence. It’s a reality of life, so how do they account for it? The Garden of Eden story seeks to answer that question, and to assert that evil stems from human behavior. God created a good world, but humans have the power to corrupt the good. Evil lacks inevitability and it also means that evil lies both within the realm of human responsibility and within human control. The Biblical writer here insists that the central concern of life is morality. And the drama of human life should revolve around the moral conflict and tension between a good god’s design for creation and the free will of human beings that can corrupt that good design.

It is by eating of the fruit, in defiance of God's command, that human beings learn that they were able to do that, that they are free moral agents. They find out that they are able to choose their actions in conformity with God’s will or in defiance of God’s will. So paradoxically, they learn that they have moral autonomy.

Remember, they were made in the image of God and they learn that they have moral autonomy by making the defiant choice, the choice for disobedience. The argument could be made that until they once disobeyed, how would they ever know that? Could the reader raise the question of whether this might be part of God’s plan, that the humans ought to know that they had free will, so that their choice for good actually becomes meaningful? Did they need to leave Eden because of their choices? Was that the plan?

Is it meaningful to choose to do the good when there is no choice to do otherwise, or that one believes that one has no choice to do otherwise? There is a thirteenth-century commentator that says that God needed creatures who could choose to obey, and therefore it was important for Adam and Eve to do what they did and to learn that they had the choice not to obey God so that their choice for God would become endowed with meaning. That is one line of interpretation that has gone through many theological systems for hundreds of years. Having knowledge of good and evil is no guarantee that one will choose or incline towards the good. That reality is what the serpent omitted in his speech. The serpent said if Adam and Eve ate of that fruit, of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, that they would become like God.

And that is true in one sense but it is false in another. The serpent implies that it is the power of moral choice alone that is godlike. But the Biblical writer will claim in many places that true godliness isn’t simply the power to do what one wishes. True godliness means imitation of God, the exercise of one’s power in a manner that is godlike, good, life-affirming and so on. So it is the Biblical writer’s contention that the God of Israel is not only all-powerful but is essentially and necessarily good. Those two elements cannot become disjoined, they must always be conjoined in the Biblical writer’s view.

And finally, humans will learn that along with their freedom comes responsibility. Their first act of defiance is punished harshly. They learn in this story that the moral choices and actions of humans have consequences that have to be borne by the perpetrator.

Before leaving this story and moving onto Cain and Abel, a couple of quick final observations.

- First of all the opening chapters of Genesis, Genesis 1 through 3, have been subjected to centuries of theological interpretation. They have generated the doctrine of original sin, which is the idea that humans after Adam are born into a state of sin, by definition. As many ancient interpreters already have observed, the actions of Adam and Eve bring death to the human race. They don’t bring a state of utter and unredeemed sinfulness. In fact what they tell us is that humans have moral choice in each and every age.

- Second of all, in this story something happens that happens over and over in the Pentateuch. God has to modify some plans, based on human actions. It can be seen in the actions of people all through the Bible. In this particular case, what has to change is the plans for the first couple, when God bars their access to the tree of life. This happens in response to their unforeseen disobedience. So despite their newfound mortality, now having to face death, humans are going to be a force to be reckoned with. They’re unpredictable to the very God who created them.

Moving on in Genesis, comes the story of Cain and Abel, which is also about the concept of Evil. What is more evil than jealousy and murder? And to murder one's own brother?

The Story of Cain and Abel

The Cain and Abel story, which is in Genesis 4:1 -16, is the story of the first murder, and it is a murder that happens despite God’s warning to Cain that it is possible to master the urge to violence by an act of will. God says:

Genesis 4:7.

"If you do well, will you not be accepted? And if you do not do well, sin is lurking at the door; its desire is for you, but you must master it".

The word “brother” occurs throughout this story repeatedly, and it climaxes in God’s question, “Where is your brother, Abel?” And Cain responds, “I don’t know; am I my brother’s keeper?” Even though Cain intends this as a rhetorical question — “Am I my brother’s keeper?” — in fact, he is right on the money. The story tells everyone that they are their brothers’ keepers, and the strong implication of the story is that all homicide is in fact fratricide. That seems to be a key message of this story.

The story of Cain and Abel is notable for another theme that recurs again and again in the Bible, and that is the tension between settled areas of agriculture and farmers and the unsettled desert areas and desert life of the nomads. Abel is a keeper of sheep. He represents the nomadic pastoralist, unlike Cain who is the tiller of soil, so he represents more settled agricultural life. God prefers the offering of Abel, and as a result Cain is distressed and jealous to the point of murder. God’s preference for the offering of Abel somehow romanticizes the free life of the nomadic pastoralist over the settled agricultural existence. Even after the Israelites settle in their own land, the life of the desert pastoralist remained a sort of romantic ideal for them. It’s a theme that comes up in many of the stories that follow. The questions that come from this underlying issue, setting aside the murder, is why God would prefer sheep to vegetables and grain? Is there something about the kind of offering that was substantially less acceptable? Is there some kind of reference here to the types of ritual offerings used much later in Israelite ceremony?

And then there is Noah

In the early narratives of Genesis, humans clearly developed some very bad habits, made some very bad choices, and as a consequence; the flood story. The message of the flood story seems to be that when humans destroy the moral basis of society, when they are violent or cruel or unkind, they endanger the very existence of that society. The world dissolves. So the story makes clear that corruption and injustice and lawlessness and violence inevitably bring about destruction. The Noah story, the flood story, ends with the ushering in of a new era, and it is in many ways a second creation that mirrors the first creation in some important ways. But this time God realizes that concessions will have to be made. God is going to have to make a concession to human weakness and the human desire to kill. And God is going to have to rectify the circumstances that made the destruction of the earth necessary in the first place. God is going to have to adjust, change plans for the humans, yet again.

So God establishes a covenant with Noah. And humankind receives its first set of explicit laws, not just the implicit concepts such as, “Murder is bad.” Humans in this story are getting the first explicit set of laws and they are universal in scope, applying to all of humanity, not just Israel. These are often referred to as the terms of the Noahide covenant.

This covenant with Noah explicitly prohibits murder in Genesis 9, that is, the spilling of human blood. Blood is the symbol of life, which is a connection that is made elsewhere in the Bible. Leviticus 17:11 says, “The life… is in the blood.” Blood is the Biblical symbol for life, but God is going to make a concession to the human appetite for power and violence. Previously humans were to be vegetarian. In Genesis 1, the portrait was one in which humans and animals did not compete for food, nor consume one another. Humans were vegetarian. Animals ate grasses and herbs.

Now God is saying humans may kill animals to eat them. But even so, he says, the animal’s life is to be treated with reverence, and the blood which is the life essence must be poured out on the ground, returned to God, and not consumed. So the animal may be eaten to satisfy the human hunger for flesh, but the life essence itself belongs to God. It must not be taken even if it is for the purposes of nourishment.

Genesis 9:4-6 says,

4 Only, you shall not eat flesh with its life, that is, its blood. 5 For your own lifeblood I will surely require a reckoning: from every animal I will require it and from human beings, each one for the blood of another, I will require a reckoning for human life.

6 Whoever sheds the blood of a human,

by a human shall that person’s blood be shed;

for in his own image

God made humankind.

The Noahide covenant also contains God’s promise to restore the rhythm of life and nature and never again to destroy the earth. The rainbow is set up as a symbol of the eternal covenant, a token of the eternal reconciliation between the divine and human realms.

This notion of a god who can make and keep an eternal covenant is only possible if one takes the view that God’s word and will are absolute, insusceptible to nullification by some superior power or some divine antagonist. This God has, and is, the ultimate power.

[Genesis chapters 6 through 9 seem to have two flood stories with distinctive styles, themes, vocabularies, and substantive details, but they are interwoven instead of being placed side by side. There are many such differing stories that come from more than one account in the Bible. This is just one of many. It isn't important to always dissect them, but knowing that more than one author had a hand in telling the story matters. It happens all through the Bible.]

The Tower of Babel

The last of the Primeval History stories is Babel. Babel, pronounced “bavel” in Hebrew, is actually Babylon. The tower in the story of the Tower of Babel is identified by scholars as a very famous tower, a ziggurat to Marduk found in Babylon. The Bible’s hostility to Babylon — it is going to be the Babylonians who are going to destroy them in 586 BCE — and its imperialism is clear. This story has a satirical tone. The word Babel, Bavel, means Gate of the God, but it is the basis for a wonderful pun in Hebrew, which also actually happens to work in English. Babble is nonsensical speaking, a confusion of language. There is obviously some onomatopoeic quality to “Babel” that makes it have that kind of a meaning both in English and a similar word in Hebrew [balbel]. This word can also, with a little bit of punning, mean confusion, or confused language. So this mighty tower that was obviously the pride of Babylon in the ancient world is represented by the Biblical storywriter as the occasion for the confusion of human language. The construction of Marduk’s ziggurat is represented as displeasing to God. Why?

There are many possible interpretations about this story, and Biblical commentaries are full of them. Some interpreters view the tower builders as seeking to elevate themselves, to storm heaven by building a tower with its top in the sky. Others see the builders as defying God’s direct order. Remember, God said, “Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth,” implying that humans are to spread out and fill the earth. But these people are said to have come together; they congregate in one place, and instead of spreading out they are trying to rise high. There seems to be a real defiance of God’s design for humanity symbolized in this tower, and so God frustrates their plan for self-monumentalizing and scatters them over the face of the earth. God makes it more difficult for them to do this building of monuments again by then confusing their tongues. Once again, God has to keep adjusting plans and actuality depending on what it is that humans are doing.

Some interpreters see this story as representing a rejection of civilization or certain aspects of civilization. Monumental architecture, empire building, these are always things that are looked upon with suspicion for most of the Biblical sources and Biblical writers. They lead to human self-aggrandizement. They are indicative of an arrogant sort of self-reliance — that the prophets will certainly rail against — and in some sense a forgetting of God. So this is a time in which humans spread out across the globe, lose their unity, and this is also a time when they turn to the worship of other gods.

The first 11 chapters of Genesis give a cosmic, universal setting for humanity. After this the narrative turns from the universal origins of humanity to the history and origins of the people of Israel. Many scholars say that one of the differences between the myths that come from the people of Israel and the mythologies of their neighbors is that, in Ancient Near Eastern mythologies, the struggle between good and evil cosmic powers is key.

These Biblical myths are telling of a struggle, but it is on a different plane. Adam and Eve, Cain, the generation of the flood, the builders of the tower of Babel — God has been continually spurned or thwarted by these characters. So God, according to the Bible, is going to choose to connect to one small group of people, as if to say, “Okay, I can’t reach everybody, let me see if I can just find one person, one party, and start from there and build out.”

Christine Hayes, Introduction to the Old Testament, Yale University: Open Yale Courses, http://oyc.yale.edu (April 2022). License: Creative Commons BY-NC-SA Some materials here used from Yale University, copyright 2007 Some rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated on this document or on the Open Yale Courses web site, all content is licensed under a Creative Commons License (Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0).

British Library Sacred Texts: Judaism, Sept. 2019, https://www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/videos/judaism.

May, Herbert G., et al. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha: Revised Standard Version, Containing the Second Edition of the New Testament and an Expanded Edition of the Apocrypha. Edited by Michael D Coogan, Oxford University Press, 2007.

Gabel, John B. The Bible as Literature: An Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2006.

“Creation from the Void: Crash Course World Mythology #2.” Crash Course: Mythology, http://spencerihs.weebly.com/uploads/1/2/1/7/121732010/creation_from_the_void_-_cc2.pdf.

- adam, meaning human, not a man ↵