The Torah

An Introduction

Some general understanding of the Hebrew texts of the Bible, their meaning and their origins, can be found by viewing this introductory video created by the British Library. When people study the Bible, it is important that they begin by realizing that the first section of books of the Bible were written by and for the Hebrew people, and are still at the heart of Judaism today. When Christianity developed, it did so because Jesus and his followers were Jews. With the expansion of the ideas and beliefs of the Jesus followers, they brought Jewish faith and writings with them into Christianity. But as anyone starts reading about and learning about the beginning of the Bible, they must start by remembering their Hebrew origins.

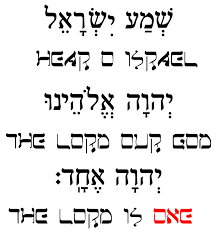

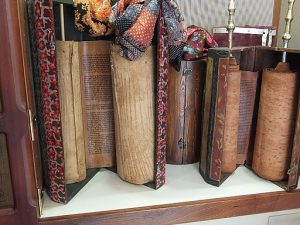

Torah (תורה) in Hebrew can mean teaching, direction, guidance and law. The Torah constitutes the first five books of the Hebrew Bible (also called the Pentateuch, ‘five books’ in Greek), traditionally thought to have been composed by Moses (in much of Judaism, this attribution of the writing of these five books to Moses is no longer thought be be true). These sacred texts are written on a scroll and reverently kept in a synagogue today.

CONTENTS OF THE TORAH

The five books of Moses, the Torah, are Genesis (Bereshit), Exodus (Shemot), Leviticus (Va-yikra), Numbers (Bamidbar) and Deuteronomy (Devarim). It was not until the 4th century BCE that the Torah became a holy object reserved for public readings. Despite the contents of the Torah not changing in millennia, the reception of the text and the way that people have interpreted it has never stopped shifting and evolving. While it is not possible to alter the content of the materials, commentaries and debates on the Torah (such as the Talmud) are still focal points in Jewish study. Throughout history, Jews have continued to produce different readings and interpretations of these texts.

The earliest commentary on the Torah, the Mishnah, was written as early as the 3rd century BCE; it is now made up of the original Mishnah and further commentaries added over the centuries that followed.

With the advent of Biblical criticism in the 19th century CE, and the challenge it presented to the doctrines of Mosaic authorship of the Torah, some conservative scholars reacted by writing commentaries intended to support the traditional views regarding Moses being the author of the five Torah books.

With the advent of Biblical criticism in the 19th century CE, and the challenge it presented to the doctrines of Mosaic authorship of the Torah, some conservative scholars reacted by writing commentaries intended to support the traditional views regarding Moses being the author of the five Torah books.

In the 20th century, however, many Jewish scholars have entered the mainstream of Biblical studies, and no longer attribute the authorship of the Torah to Moses.

The three main denominations of Judaism (Orthodox, Conservative and Reform) have also produced one-volume Torah commentaries for use in synagogues to accompany the public reading of the Torah, each reflecting its denomination’s ideology and relation to sacred scripture. The majority of modern Biblical scholars now regard the authors of the Torah books to be multiple people, coming from various perspectives, and edited by rabbis into this whole. Oral tradition was important to this process, and so was the role of scribes and editors in the interpretation of what was to be written down.

Genesis: Chapters 1-11 relate God’s creation of the world and the first humans, the stories of Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, the flood, the tower of Babel, and the invention of various human arts and industries. These 11 chapters are called Primeval History (history being a less than useful term, given how we approach history in modern times) and are in reality the origin myths from Judaism for all of humanity.

Chapters l2-50 contain the stories of the patriarchal and matriarchal ancestors of the Israelites: Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebekah, Jacob and Leah and Rachel. The descent of the Jacob’s son Joseph into Egypt, his rise to power and the eventual arrival of all of the Israelites in Egypt are stories that are also included. These stories, and those to follow, are considered Ancestral History (again some problems with the term history) and while they are not about all of humanity, but instead about the Hebrew people, they are still stories, not history. There is no real evidence supporting the existence of these specific people, but instead excellent research into the beginnings of the Hebrew people in the region. Archaeology has a lot to say about this movement of the people that is more factual, and less faith based.

Exodus: Contains the story of Moses who is charged by God with leading the Israelites from Egypt where they have been enslaved. At Mount Sinai in the wilderness, God enters into a covenantal relationship with Israel, imparting divine instructions which the Israelites promise to obey. Includes instructions for the construction of God’s tabernacle. No specific Pharaoh is identified to help solidify dates for these slaves, but the story, again, is about salvation from suffering, and not a historic rendering of actual events.

Leviticus: Contains instructions concerning the sacrificial cult and other priestly rituals, the initiation of Aaron and his sons as priests, as well as laws concerning purity and impurity (both ritual and moral).

Numbers: Continues the narrative of the Israelites as they wander in the wilderness. Further instructions about various rituals and activities are given in this period.

Deuteronomy: Contains a set of three speeches delivered by Moses on the plain of Moab on the eastern side of the Jordan river, as the Israelites are poised to enter the promised land. Moses reiterates the divine instruction delivered at Sinai and charges the people to be faithful to God so as not to incur his displeasure. Moses dies without entering the Promised Land. Joshua takes over as leader of the Israelites.

British Library, Discovering Sacred Texts, https://www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/videos/judaism.

Saunders, MaryAnne. “The Torah.” British Library, Discovering Sacred Texts, 23 Sept. 2019, https://www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/articles/the-torah.

Walfish, Barry Dov. “Jewish Bible Study.” British Library, Discovering Sacred Texts, 23 Sept. 2019, https://www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/articles/jewish-bible-studies.

May, Herbert G., et al. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha: Revised Standard Version, Containing the Second Edition of the New Testament and an Expanded Edition of the Apocrypha. Edited by Michael D Coogan, Oxford University Press, 2007.

Gabel, John B. The Bible as Literature: An Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2006.

Hayes, Christine. “Introduction to the Old Testament (Hebrew Bible).” Introduction to the Old Testament (Hebrew Bible) | Open Yale Courses, https://oyc.yale.edu/religious-studies/rlst-145.

Copyright © 2007 Yale University. Some rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated on this document or on the Open Yale Courses web site, all content is licensed under a Creative Commons License (Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0).

5 books of the Hebrew Teachings--Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy

a set of explanatory or critical notes on a text.

the term used to describe the earliest stories in Genesis about the origins of humanity. Not history as any modern person would understand the term.

Not like modern history, but the stories in the Torah about the origins of the Hebrew people, from Abraham through to the era of the Judges

In the Hebrew tradition, salvation is a term used to describe actual physical saving from danger, oppression, suffering and slavery. In the Christian tradition the term salvation is used to describe the personal relationship of a person with the divine, that a person is in a right relationship with God and is delivered from the consequences of sin