21 Revelation

The Apocalypse, or the Revelation of John, shares many of the traits found in the genre of apocalyptic literature. One major trait is that it operates in dualisms–earthly events are contrasted with heavenly ones, and the comparison is made of present time with the coming future. Its structure is often such that the reader experiences crisis and then catharsis while reading through the materials. Politically, the Revelation of John equates Rome with ancient Babylon, the conqueror and destroyer of Israel, and Rome’s empire as the reign of evil, that of Satan.

The Greek word apocalypsis just means “the uncovering,” and it refers to an entire genre of literature of the ancient world, much of it Jewish in origins. There are some other apocalyptic stories from around the world, but in modern days, most of what is described as apocalypse comes from either an ancient Jewish or ancient Christian set of beliefs.

Daniel is a major Hebrew Bible source of apocalypse. The two most apocalyptically oriented books in the Bible are Daniel and Revelation. Like in the book of Daniel, any apocalyptic writings (remember–there are some of this kind of writing found in the prophets, the gospels and the epistles, too) usually tells what is going to happen in the future. The future is never the actual and complete end of the world, however. Usually an apocalypse does have a massive destruction of people, places, and things, but then also contains a re-creation of some kind of physical world, with new structure and powers. A summary might say that an apocalypse is, even in spite of terror, destruction and grief, calling into being the Kingdom of God.

In the ancient world there were many apocalyptic writings. These writings seemed to reflect some of the tone of the era, the tone within religions, a portion of Mediterranean cultures, and a focus for society at large.

Dr. Michael White[1] says,

Scholars also talk about “apocalyptic” or “apocalyptic environment,” or “apocalyptic outlook.” In this sense the word “apocalyptic” has a slightly broader meaning, and it refers to the spirit of the age that especially became prominent roughly between the years 300 B.C. and 200 C.E., the very years in which Judaism itself went through some cataclysmic changes, when the Temple was destroyed once again and importantly when the Christian movement itself was born and Jesus was executed.

Usually an apocalypse has a chronological span of time–now and soon to come. There is a structure of the time “before” and the time “after” in the New Testament: the “now time” which is still going on, and the “future time” which has already started impinging on the present. There will generally be a narrative in an apocalypse that says to the reader that first this catastrophe or sign happens, then this place or person is destroyed, then finally the true end comes in catastrophe, and after that–a new beginning can occur, an era of hope. This new era is generally thought of as a time of goodness or purity, a time of what Judaism and eventually Christianity called the Kingdom of God on earth.

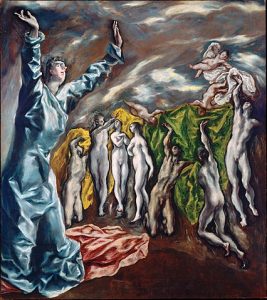

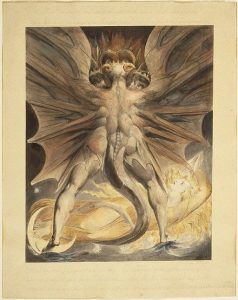

The various apocalypses also have all kinds of vibrant images, both good and bad; angels, demons, sometimes various beasts, often some monstrous beasts, symbols of light, and symbols of dark. The list of characters and the symbols that they convey are fairly universal from writing to writing. The author of an apocalypse will often start by conveying a dream that they had, and what an angel or a deity or some messenger told them and showed them in that dream. In any apocalypse there is often a structure containing different layers of heaven and hell, or of good and evil.

There is also the world view of apocalypticism–“here on earth” and “up in heaven”. Paul never wrote an apocalypse, and yet his letters show an apocalyptic world view, focusing on an urgent and imminent coming again of Jesus. The Gospel of John shows an ethical dualism between good and evil, with Jesus’s ministry signaling the beginning of the Kingdom. In apocalypses there is frequently a spatial dualism, too, with “up there” and “down here” clearly separated, so that things that occur on earth are simply shadows of what is going on in the heavens. This apocalyptic world view describes everything that goes on in our world as simply being a mirror image of the battles that are going on the heavens.

The event in Christian apocalypse that marks the beginning of the end time has been the cross and the resurrection of Jesus. Jesus was raised. And what is happening when people are being raised from the dead? At that point, the end of the world has happened or is happening. The dead are to be physically raised from death, according to Jewish mythology, and this is something that only happens at the end of time.

The earliest Christians were Jews expecting an apocalyptic Kingdom of God to happen, and Jesus taught this himself as an apocalyptic prophet. But when Jesus was killed, then the whole thing seemed to go awry because the Messiah was not supposed to be killed, according to Jewish belief and prophecy. The followers of Jesus believed they had seen the resurrected Jesus, however, three days or more after his death. And that meant they thought that the end time must have already started, since resurrection from the dead was starting.

Paul talked about Jesus as the “first fruits of those who sleep.” That meant that Jesus was just the first of those who would be raised, and all the rest of the believers would be raised when the final end time came. So early Christians believed the end started with the resurrection of Jesus. But they also knew the full end had not yet come because the Kingdom of God was not really totally visible yet. The Romans were still in charge at the time.

The Christians expected Jesus to come back down, to come from heaven. In the first letter to the Thessalonians, Paul talks about how Jesus will come back to earth, and then how believers will fly up in the air and meet him. That is called the parousia, which is a Greek term that just means “presence” or “coming.” Christians lived, according to Paul’s theology, right in this middle time between the “before” and the “after”. All these different dualisms are characteristics of apocalypse, both in the big book of Revelation, as well as in smaller parts of other Christian writings.

Dr. Paula Fredericksen[2] says:

“As long as the empire was pagan, Rome could be an historical stand in for Babylon. After all, that’s what the text of apocalypse says. The awkwardness for Christianity, with its own apocalyptic heritage, comes with Christianity’s political success. When Constantine converts to one, remember, just one form of Christianity … in 312 CE, from the perspective of John, the writer of Apocalypse, the beast has entered the church. But from the point of view of Eusebius, one of Constantine’s Bishops, it’s God’s working in history. It’s the revelation of the messianic peace that Isaiah talked about. From Eusebius’ perspective–I mean we’re used to thinking of the empire being Christian, they weren’t, it just happened in their lifetime–this is an unthinkable thought and yet it occurs.

So Eusebius, looking at these traditional apocalyptic texts, knows that the traditional apocalyptic reading has to be wrong, because now the empire is Christian. …The empire is not God’s opponent, and therefore, interpretations that look at these texts as speaking about God defeating the evil empire of Rome are clearly wrong interpretations, because now God’s servant is himself the emperor.”

Take the time to read an excellent article on Elaine Pagel’s studies concerning Revelation, found in the Harvard Gazette, 2009.

Examples: Why a book on Revelation? How have people over the centuries used Revelation?

Often apocalypses seem to have served as a form of cultural resistance. They make the most sense to a resistance movement, being popular among people who are oppressed by some more powerful entity– or who at least believed that they are oppressed. There is no way these early Christians groups, or even the nation of Israel, could rebel against the Roman Empire and win. The idea then was that the small groups would resist as best they could, and eventually God would enter history with angels and divine armies, and people would fight alongside to overthrow the earthly power.

History clearly had a powerful influence on John of Patmos, the writer of Revelation, including the Jewish uprising against Rome (66-70 CE), which led to the destruction of Jerusalem by victorious Roman armies.

In the earliest apocalypses, Daniel was talking about the Greco-Syrian Empire as the first oppressive power that people thought they could overthrow this way. Then of course the Romans became the more oppressive power, so in Jesus’ time and then in Paul’s time it becomes the Romans who are the enemy that will be overthrown.

It is not always true that the people who believe in these kinds of apocalyptic ideas are themselves an oppressed minority. Many wealthy and famous people have, and still do, believe that God is going to come again to earth any day. It does not always mean that people who hold these views are discriminated against or are oppressed minorities, but it usually means that they perceive themselves that way. It is when people do not have the power politically or militarily to fix problems that this kind of apocalyptic world view becomes very persuasive and very plausible.

The introduction to Revelation says that it is written by a man named John, known often as John of Patmos. It is not the same John who was the brother of Zebedee, it is not the same John (if there was a writer named John) who wrote the Gospel of John or the letters of John. Whoever wrote Revelation is not the same person who wrote any of that literature. The writing style is too different and the theology is too different, as well. He doesn’t claim to be any famous John, he just claims to be John, often called John the Seer or John the Prophet. Interestingly enough, this John does not place the composition of his book centuries in the past, and the predicting the future, but in his own time, which was late first century CE. John really believed that the end times had already begun in Jesus, and in his death and resurrection. John is a Jew, and sees himself as a prophetic figure like Daniel, but as a prophetic figure not for the future, as he does not believe there is going to be any more future. He believes that Jesus is coming back right now, so he places himself right at the beginning of that event and becomes a prophet for the current times. Jewish apocalypse was often written in a kind of allegory or code, and John of Patmos wrote in that style as well. The difference between John’s writing and that of Paul was the approach to Rome. Paul advocated the Christians to live in peace with their neighbors. John advocated resistance in his own time.

As time went on, however, generations passed, and the Roman Emperor became Christian himself and thus a symbol of Christ on earth. The book of Revelation with all its “reject and resist the power of Rome” then became a problem for scholars who were considering what to include in the Bible. Revelation almost did not make the list!

The Structure of Revelation

The Book of Revelation was likely written right at the end of the first century CE. The traditional story of the Book of Revelation is that John wrote this while he was in exile on the Greek island of Patmos. In a dream he saw a vision, this revelation of the future of the world. He is told, first off, to write some letters to Ephesus, Smyrna, Pergamon, Thyatira, Sardis, Philadelphia, and Laodicea. These are seven churches located in Asia Minor.

Revelation has an interesting structure, after the introduction at the beginning and after the seven letters to the churches of Asia Minor are concluded. Revelation was written about the actual time in which John was writing. Very conservative Christians tend to read it instead as being about their own immediate time–and Christians have been doing this same thing for many centuries. Once the events of Revelation clearly did not happen at the end of the first century, then it has been read by Christians in every time to be about what they saw as being especially horrific– medieval plagues, the Protestant Reformation, the English civil wars, World War I and World War II, or most recently as seen in The Late Great Planet Earth. Cult leaders have often used Revelation over the centuries to support their teachings. Some even say Revelation is about the Soviet Union versus the United States of America, and that everything that it talks about is referring to what is going to happen in this century between those two super-powers.

The Book Revelation doesn’t give any kind of a strict timeline for its events, however, even though it reads as if this is all going to happen right away. In fact, it seems to have cycles in its narrative that set up a crisis when all these terrible things happen, and then something finally happens that serves as a quasi-resolution to the story. But as the reader continues on after some kind of resolution or pause in the terror, a new cycle starts, and suffering and struggle happens all over again. After several cycles, there is a cataclysmic crash finale that comes at the end of the Book of Revelation.

So–first comes an introduction, and then the seven letters to the churches. After this, Revelation has 3 big sections and a finale.

The sections start, more or less, with chapter 6 of Revelation. This is the first of the 3 big sections, and it is focused on the opening of seven seals.

Written work in that era was primarily recorded in scrolls, not in books with all the different pages all sewn together. What John is imagining and writing about is a huge scroll. In that time, when something written was completed, the scroll was rolled, and a wax seal added at the end of the roll which sealed the work shut. Anybody who wanted to read it had to break that wax seal. The seals that John is talking about are multiple wax seals on a scroll. Imagine a scroll that has one seal, and when broken the reader unrolls the scroll a little bit, gets to another seal, undoes that seal, unrolls it a little bit more– and so in Revelation, the angel is gradually unrolling this big scroll. And out of the scroll’s narrative jump these horses. (The image at the beginning of this chapter shows the 4 horses portrayed in art…)

The first seal releases a horse that looks like Empire, the image of the conqueror:

Then I saw the Lamb open one of the seven seals, and I heard one of the four living creatures call out with a voice of thunder, “Come!” I looked and there was a white horse. Its rider had a bow, a crown was given to him, and he came out conquering and to conquer.

The second seal is about general warfare.

He opened the second seal. I heard the second living creature call out, “Come!” And out came another horse bright red. Its rider was permitted to take peace from the earth so that the people would slaughter one another and he was given a great sword.

The third seal is about famine and poverty:

When he opened the third seal, I heard the third living creature call out, “Come!” I looked and there was a black horse. Its rider had a pair of scales in his hand, and I heard what seemed to be a voice in the midst of the four living creatures saying, “A quart of wheat for a day’s pay and three quarts of barley for a day’s pay, but do not damage the olive oil and the wine.”

The fourth seal is Death:

When he opened the fourth seal I heard the voice of the fourth living creature call out, “Come!” And I looked and there was a pale green horse. Its rider’s name was Death, and Hades followed with him. They were given authority over a fourth of the earth to kill with the sword, famine, and pestilence, and by the wild animals of the earth.

After these 4 images, John is suddenly not talking about horsemen anymore. Four horsemen representing four different things popped out from their seals, but when the fifth seal is described, John takes things in a different direction.

The fifth seal is not another horse.

Under the altar, the souls of those who had been slaughtered for the word of God and for the testimony they had given, they cried out with a loud voice, “Sovereign Lord, holy and true, how long will it be before you judge and avenge our blood on the inhabitants of the earth?” They were each given a white robe and told to rest a little longer until the number would be complete, both of their fellow slaves [it says “slaves” actually in the Greek, not “servants”] and of their brothers.

The fifth seal gives a vision of the altar of God in heaven. And under the altar are the souls of all the followers of Jesus who have been martyred up to this time. The fifth seal is actually pause which tells the audience that if they suffer in this present time it will be taken care of by God. The first four seals are the building up of terrible things, and the fifth is a moment that pauses in the narrative of horrors and instead gives comfort to the reader.

And then comes the sixth seal:

He opened the sixth seal, I looked and I heard a great earthquake, the sun became black as sackcloth, the full moon became like blood, the stars of the sky fell to the earth as a fig tree drops its winter fruit when shaken by a gale. The sky vanished like a scroll rolling itself up.

Every mountain and island moved from its place. Then the kings of the earth, and the magnates and the generals, and the rich and the powerful, and everyone, slave and free, hid in the caves, and among the rocks of the mountains, calling to the mountains and rocks, “Fall on us and hide us from the face of the one seated on the throne, and from the wrath of the Lamb! For the great day of their wrath has come, and who is able to stand?”

The sixth seal shows the cosmos coming down on top of itself. John has by this time created a severe level of anxiety and catastrophe. And John is not in a hurry to get to the seventh seal. Instead, there is a bit of a pause again in the narrative, and something interesting happens.

In chapter 7 the followers of Jesus are numbered into different tribes, consisting of 12,000 people each, and then each of those tribes is “sealed”. This is a different use of the term “to seal”. In this use of the term, a seal is put on the faces of all the people who are the true followers, who are the true Israel. Israel is reconstituted in this story and sealed. It means that anyone with a seal on them will not be harmed in the terrors to come.

Where is the seventh seal? The reader goes all the way through chapter 7 wanting the seventh seal but John is making the reader wait, but it is only because he is reassuring the reader.

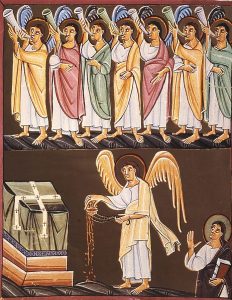

At Revelation 8:2 the seventh seal finally is revealed:

“When the Lamb opened the seventh seal there was silence in heaven for a half an hour.”

That is the seventh seal. The text builds up tension, but the seventh seal is — silence in heaven for a half an hour.

In a brief summary of that first cycle, then, there are four seals which contain awful things, and a slight change of pace occurs in the fifth seal, which tells the souls who have been martyred not to worry, that they will be saved. Then the sixth seal is horrifically bad and goes on for a long time. And before the last seal opening comes the sealing of the followers of Jesus with salvation. After that digression comes this seventh seal of silence, silence in heaven for a half an hour.

The writing shows a cycle of catastrophes, ending with something good. In a simple format, that is the way Revelation is structured, having three different cycles of seven.

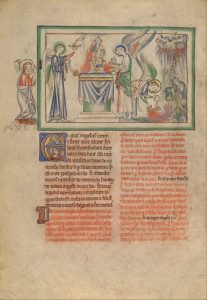

circa 1000

The second section of Revelation, its second cycle of catastrophe, starts in chapter 8.

Revelation 8:2 gives an introduction to seven angels with seven trumpets.

The first, second, third, and fourth trumpet announce catastrophes.

7 The first angel blew his trumpet, and there came hail and fire, mixed with blood, and they were hurled to the earth, and a third of the earth was burned up, and a third of the trees were burned up, and all green grass was burned up.

8 The second angel blew his trumpet, and something like a great mountain, burning with fire, was thrown into the sea. 9 A third of the sea became blood, a third of the living creatures in the sea died, and a third of the ships were destroyed.

10 The third angel blew his trumpet, and a great star fell from heaven, blazing like a torch, and it fell on a third of the rivers and on the springs of water. 11 The name of the star is Wormwood. A third of the waters became wormwood, and many died from the water because it was made bitter.

12 The fourth angel blew his trumpet, and a third of the sun was struck, and a third of the moon, and a third of the stars, so that a third of their light was darkened; a third of the day was kept from shining and likewise the night.

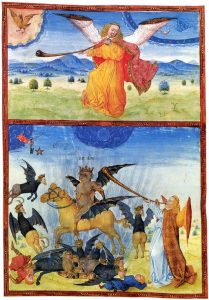

15th century

And then comes an interlude where an eagle comes through and announces woes on everybody.

The fifth trumpet shows up in 9:1-12 giving power to a “star fallen from heaven”, and the sixth trumpet arrives in 9:13 full of massive death and destruction.

Then comes a pause, similar to the pause in the first cycle which talked about the sealing of the tribes of the new Israel. Chapter 10 in the second cycle is about the scroll of prophecy. Chapter 11 talks about the temple.

And finally in 11:15 comes the seventh trumpet. And what does the seventh trumpet introduce? Praise in heaven, something like that half hour of silence from the first section or cycle.

15 Then the seventh angel blew his trumpet, and there were loud voices in heaven, saying,

“The kingdom of the world has become the kingdom of our Lord

and of his Messiah,

and he will reign forever and ever.”

A long interlude follows in chapters 12, 13, and 14, which is about battles between the woman who is the mother of church (or of the Savior–interpretation differs), and the dragon. Chapter 13 is about the dragon and the beast. Chapter 14 is about the horned lamb which represents Jesus.

Starting in 15:1 comes a third cycle, consisting of seven angels and seven plagues or bowls. The bowl contents start in chapter 16:

Then I heard a loud voice from the temple telling the seven angels, “Go and pour out on the earth the seven bowls of the wrath of God.”

2 So the first angel went and poured his bowl on the earth, and a foul and painful sore came on those who had the brand of the beast and who worshiped its image.

3 The second angel poured his bowl into the sea, and it became like the blood of a corpse, and every living thing in the sea died.

4 The third angel poured his bowl into the rivers and the springs of water, and they became blood. [a hymn is included here]

8 The fourth angel poured his bowl on the sun, and it was allowed to scorch people with fire; 9 they were scorched by the fierce heat, but they cursed the name of God, who had authority over these plagues, and they did not repent and give him glory.

10 The fifth angel poured his bowl on the throne of the beast, and its kingdom was plunged into darkness; people gnawed their tongues in agony 11 and cursed the God of heaven because of their pains and sores, and they did not repent of their deeds.

12 The sixth angel poured his bowl on the great River Euphrates, and its water was dried up in order to prepare the way for the kings from the east.

And then comes the seventh bowl, offering a conclusion–of sorts.

17 The seventh angel poured his bowl into the air, and a loud voice came out of the temple, from the throne, saying, “It is done!” 18 And there came flashes of lightning, rumblings, peals of thunder, and a violent earthquake, such as had not occurred since people were upon the earth, so violent was that earthquake. 19 The great city was split into three parts, and the cities of the nations fell. God remembered great Babylon and gave her the wine cup of the fury of his wrath.

Then, after these 3 cycles, finally comes the great conclusion, the destruction of Rome in chapters 17-19. The final battle is in chapter 19:11-21, the imprisonment and eventual destruction of enemies is in chapter 20, and the establishment of the new Jerusalem is in chapters 21 and 22.

Revelation was written to be heard read out loud, but why was it written? This is a documentary by BBC that contains a great deal of excellent material about the origins, author, meaning and intent of Revelation.

Crisis, Catharsis, and the Social Setting in Revelation

The writer of Revelation is writing what comes across as a dramatic myth, and in it the whore, Babylon, is killed. This concept of a whore really just means that symbolically, Rome, as the “whore”, is going to be destroyed. Within Rome, all the wealthy people and all the kings of the earth will be destroyed by the angels, too, and a fairly militant savior Jesus is going to come down to earth. New Jerusalem is then going to be built all gold and beautiful, and there will be no night nor day there because God is light –and then everybody will live happily ever after.

It is important to go back to the beginning of Revelation at this point to understand John’s perspective as he writes to the 7 churches of Asia Minor.

John starts Revelation off with the seven short letters to seven churches. Here is what John says to the church in Ephesus:

These are the words of him who holds the seven stars in his right hand, who walks among the seven golden lamp stands. I know your works, your toil, and your patient endurance. I know that you cannot tolerate evil doers, you have tested those who claim to be apostles but are not, and have found them to be false. I also know that you are enduring patiently and bearing up for the sake of my name, and that you have not grown weary. But I have this against you …

In reading it becomes clear that some portions of each of the seven letters contain praise to the churches, and some portions are more scolding content. What are they doing that John doesn’t like? He is fairly clear about his complaints concerning behavior in these churches.

This is written to Pergamum, which happened to be a major site for the Imperial Cult, the cult that worshiped the emperor. In 2:13 John writes:

13 “I know where you are living, where Satan’s throne is. Yet you are holding fast to my name, and you did not deny your faith in me even in the days of Antipas my witness, my faithful one, who was killed among you, where Satan lives. 14 But I have a few things against you: you have some there who hold to the teaching of Balaam, who taught Balak to put a stumbling block before the people of Israel, so that they would eat food sacrificed to idols and engage in sexual immorality.

A great deal of meat available for sale in the region was meat that came from sacrifices in temples. When temple ceremonies were done, the meat from them then came to market places to sell to ordinary people. John doesn’t like people who are eating meat sacrificed to idols. He seems to know that there are some Christians who eat meat sacrificed to idols, and he calls that idolatry.

To the church in Thyatira, John writes in 2:19

19 “I know your works: your love, faith, service, and endurance. I know that your latest works are greater than the first. 20 But I have this against you: you tolerate that woman Jezebel, who calls herself a prophet and is teaching and beguiling my servants to engage in sexual immorality and to eat food sacrificed to idols. 21 I gave her time to repent, but she refuses to repent of her sexual immorality. 22 Beware, I am throwing her on a bed, and those who commit adultery with her I am throwing into great distress, unless they repent of her doings, 23 and I will strike her children dead.

Both the sin of eating meat sacrificed to idols and sexual immorality, including adultery, are considered unacceptable in this letter.

Several other problems are identified in each letter, but this is a vivid chastisement found in the letter to Laodicea in 3:15

15 “I know your works; you are neither cold nor hot. I wish that you were either cold or hot. 16 So, because you are lukewarm and neither cold nor hot, I am about to spit you out of my mouth. 17 For you say, ‘I am rich, I have prospered, and I need nothing.’ You do not realize that you are wretched, pitiable, poor, blind, and naked.

Having no real passion for the faith is apparently unacceptable. And this lukewarm approach to faith, even a complacent comfort with the status quo, this is perhaps one of the biggest reasons that John is writing Revelation for these churches. People in the various house churches are becoming comfortable with Roman rituals and ideas, while still claiming that they are Christians. John does not find this combination acceptable.

Adela Yarbro Collins[3] wrote a book called Crisis and Catharsis about the book of Revelation. Her thesis was that the purpose of Revelation was to build up a sense of crisis in the early followers of Jesus. Revelation is addressed to these groups of early Christians and it obviously wants them to be uncomfortable with Roman rule. She writes saying that John clearly worries that Christians have become too comfortable with Roman rule, with Roman lifestyles, and with all the religious Roman practices. So a kind of crisis of faith is intentionally created by the book of Revelation in order to let people experience, after experiencing the crisis, a catharsis of salvation through Jesus. The structure of Revelation tries to work that crisis-catharsis process out psychologically in those Christians who hear this dramatic story. The book creates fear in order to remind people that Jesus is the way beyond any fear that they might suffer. But if the people are not concerned about Rome–they should be!

Revelation is meant to be read out loud. One might even call it performance writing. Imagine a gathering of Christians in Asia Minor in their church, still meeting in someone’s house. Someone known to the group has sent this document to them, and asked that it be read to the group. It contains all kinds of strange creatures, angels singing, monstrous beasts, dragons, and even glimpses of heaven with its altar and throne. The whole story is vivid and almost unbelievable. It captures the imagination of the people hearing it, but more, it serves as a warning of a crisis that the people did not necessarily realize existed.

John does not write this because he wants the believers to live in crisis, however. John believes that God is going to take care of the crisis eventually– but not necessarily today. John just wants the people to be very aware that Roman influences are insidious and perhaps even dangerous to them and to their faith.

The Book of Revelation seems to have a dual purpose. There is a saying that good preaching is supposed to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable. That affliction and comforting of people is part of what the Book of Revelation tries to do.

The images in Revelation certainly refer to Rome. Babylon is the code name for Rome here. Revelation 17:9 and 18 talk about this city being on seven hills, referring to the famous Seven Hills of Rome.

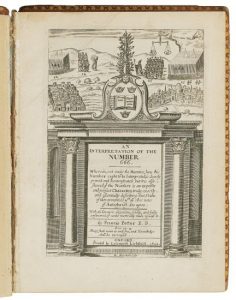

And then, of course, comes that far too well known and poorly understood reference found in chapter 13:18

“… so that no one can buy or sell who does not have the mark of the beast, the name of the beast or the number of its name. This calls for wisdom, let anyone with understanding calculate the number of the beast, for it is the number of a person. Its number is 666.”

What does that much debated and feared number 666 mean? Written in Aramaic, this can be valued at 666 using the Hebrew numerology of gematria, and was used to secretly speak against the emperor. Nero Caesar in the Hebrew alphabet, which when interpreted numerically adds up to 666. Other ancient authorities say the number is actually supposed to be 616, because if Nero’s name is spelled in an alternative possible spelling from within the ancient world, it comes out to be 616 rather than 666. But however one adds it all up, this whole numerology process leads scholars to think the writer is probably referring to Nero in the narrative. Nero is a beast, and Rome is called the whore that has had sex with every rich man and every king throughout the whole world. This is not a very positive view of Rome! It becomes clear that Rome is completely destroyed at the end of the book.

A few scholars believe that Revelation was written in the 60s when Nero was himself was alive and emperor. Many more tend to believe that it was written toward the end of the first century, when Nero was already dead. There was a great myth from the ancient world called Nero redivivus. The myth was that Nero was such a terrible man that even though he had been assassinated, he was going to rise from the dead someday and raise a new army. Some even had the idea that Nero was still alive somewhere and was raising an army of Parthians to wage war and eventually take over the Roman Empire again.

This was especially chilling for followers of Jesus because Nero was well known, at the end of the century, for being the first emperor to have persecuted the followers of Jesus in Rome. The famous story is that there was a big fire in Rome, and Nero was blamed for the fire because he was clearing a bunch of apartment buildings of lower income people out of a certain area of Rome, right by the Coliseum, to build his huge new palace. Because this whole destruction of the homes of the poor was so unpopular, Nero instead blamed the fire on the Christians. He said that the Christians set the fire, and were truly terrible people. After much persecution, torture and suffering, Christians were killed because of this accusation made by Nero. For followers of Jesus, Nero was a ominous and frightening figure.

General ideas in the population concerning what is found in Revelation are often wildly inaccurate. Some thoughts about end times are not actually found in this particular apocalypse at all.

Dr. Michael White has some helpful thoughts about how people have taken some basic ideas of end times from Revelation, and added to them ideas that actually occur other places in the Bible:

Sometimes people are surprised that when they actually read the Book of Revelation what’s not there. Things that are typically associated with end time prophecies and typical language actually is not found in Revelation at all. … Notably there’s no reference whatsoever to the Antichrist. That terminology only shows up in two places in the entire New Testament. One time in First John and one time in the Second John, but not in the Book of Revelation itself. The other terminology that [is] sometimes thought to be in Revelation is the Rapture, that is, the snatching away of Christians just at the last moment before the Tribulation occurs. That, likewise, is not actually in the Book of Revelation itself, that actually comes from a passage in First Thessalonians. And so what we have to realize is that in some interpretations of the Book of Revelation–in fact most of them–the interpretation is created by bringing things into the Book of Revelation, into its scheme, that are not actually there and reading them as a kind of a jigsaw puzzle of eschatology and last judgment.

The ending of the Book of Revelation is meant to be a description of the Kingdom of God. It is symbolized by the rebuilding of the city of Jerusalem and the temple there, honoring the God of Judaism, of Jesus’ Father. Chapter 21 starts describing this:

Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and the sea was no more. 2 And I saw the holy city, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband. 3 And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying,

“See, the home of God is among mortals.

He will dwell with them;

they will be his peoples,

and God himself will be with them and be their God;

4 he will wipe every tear from their eyes.

Death will be no more;

mourning and crying and pain will be no more,

for the first things have passed away.”

5 And the one who was seated on the throne said, “See, I am making all things new.” Also he said, “Write this, for these words are trustworthy and true.”

The final chapters of Revelation talk about a gorgeous place, full of goodness and truth, and end with an epilogue, where John asserts the truth, the importance, and the imminence of all of this. John has been told not to seal up this scroll, this prophecy, because it is going to happen now.

Reading Revelation is easier when the social conditions of the churches in the Mediterranean at the time of its writing are clear, when some history of apocalypse is known, and when symbolism is analyzed. Then the “code” that seems to be in place here is simpler to understand.

Since the time of John of Patmos, people have interpreted and reinterpreted Revelation in many ways. The Book of Revelation has come to be read as prophesying the events of the end of history–whenever that might be, and if it ever actually happens! In it people say that there will be tough times, a resurrection of believers, judgment of all people, and a new age, built on God’s reign.

Dr. John Collins[4] says this about Revelation, as a good summary:

With a book like the Book of Revelation, you will inevitably have several central messages depending on the angle from which you look at them. Some people see it primarily as a political statement, where the central message is resistance to tyranny, as exemplified in that case by the power of Rome. Other people would see it as a more spiritual book where the emphasis is on the end product, where everybody gets to sing like the angels in heaven and where detachment from this world is the central point of it. I suppose you would have to say that the central message encompasses both of these. That on the one hand there is there a rather terrifying vision of this world, as a place that is brutal, where savage powers are let loose, but also then that sees this world in perspective, where the powers of this world are passing away, and I suppose I would say at the end of that is the basic message of the book. That the powers of this world, no matter how terrifying they may be, are passing away and that in the end righteousness and justice will prevail.

Tabor, James, et al. “Apocalypticism Explained | Apocalypse! Frontline.” Frontline: From Jesus to Christ, Public Broadcasting Service, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/apocalypse/explanation/brevelation.html.

May, Herbert G., et al. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha: Revised Standard Version, Containing the Second Edition of the New Testament and an Expanded Edition of the Apocrypha. Edited by Michael D Coogan, Oxford University Press, 2007.

Gabel, John B. The Bible as Literature: An Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2006.

Collins, Adela Yarbro. Crisis and Catharsis the Power of the Apocalypse. Westminster Press, 1984.

Pagels, Elaine. “Why Did You Write a Book about The Book of Revelation? Dr. Elaine Pagels.” MythVision Podcast, 8 July 2021, https://youtu.be/1EFpEqLE9kE.

“Bible Mysteries: Revelation, the End of the World” English Documentary on BBC Part 1.” BBC, 14 Sept. 2017, https://youtu.be/z1Hi48DABrw.

Ireland, Corydon. “Revelations on Revelation.” Harvard Gazette, Harvard Gazette, 7 Dec. 2009, https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2009/12/revelations-on-revelation/.

Dale Martin, Introduction to the New Testament, Yale University: Open Yale Courses, http://oyc.yale.edu. License: Creative Commons BY-NC-SA . Most of the lectures and course material within Open Yale Courses are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 license. Unless explicitly set forth in the applicable Credits section of a lecture, third-party content is not covered under the Creative Commons license.

- White is Professor of Classics and Christian Origins at the University of Texas at Austin, and acted as historical consultant for "Apocalypse!" ↵

- is a William Goodwin Aurelio Professor of the Appreciation of Scripture at Boston University. She specializes in the social and intellectual history of ancient Christianity. She is the author of From Jesus to Christ: The Origins of the New Testament and Images of Jesus and has written on conversion, apocalypticism and Jewish/Gentile relations in Late Antiquity. ↵

- Professor Yarbro Collins joined YDS in 2000 after teaching at the University of Chicago Divinity School for nine years. Prior to that, she was a professor in the Department of Theology at the University of Notre Dame. Her first teaching position was at McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago. She was president of the Society for New Testament Studies in 2010-2011 and president of the New England Region of the Society of Biblical Literature in 2004-2005. She was awarded honorary doctorates in theology by the University of Oslo, Norway, in 1994 and by the University of Zurich in 2015. She was granted a Fellowship for University Teachers by the National Endowment for the Humanities for 1995–96. Her most recent books are New Perspectives on the Book of Revelation (editor; 2017), King and Messiah as Son of God, coauthored with John J. Collins (2009), and Mark: A Commentary in the Hermeneia commentary series, published in 2007 ↵

- is a Professor of the Hebrew Bible at the University of Chicago Divinity School. He is best known for his work on Jewish apocalypticism. His works include The Apocalyptic Imagination" and is co-editor of "The Encyclopedia of Apocalypticism. ↵

s the practice of assigning a numerical value to a name, word or phrase according to an alphanumerical cipher. A single word can yield several values depending on the cipher which is used.

Hebrew alphanumeric ciphers were probably used in biblical times, and were later adopted by other cultures.