The Earliest Christians

The First Christians

The earliest people who followed Jesus were, of course, Jews. And this was because the disciples assumed that Jesus was a Jewish messianic figure, come to fulfill prophecies found in the Hebrew prophecies. So they believed that this messiah had come specifically to the Jewish people, not as some world saving figure. But the disciples were living and working and preaching in a country occupied by Romans and visited by foreign traders of all kinds, and these Gentiles started hearing about this Jewish teacher. It didn’t take long for Gentiles who were interested in the Jesus movement to start asking for “membership” in the group, wanting baptism, teaching, inclusion.

The early history of the people who were eventually called Christians is found in the Bible in two basic formats–the Epistles and the book of Acts. Acts is a narrative concerning, mostly, the activities of Peter and the original disciples, and the journeys and church-creating of the apostle Paul of Tarsus. Acts is a set of stories, almost a history, likely written by the same author who wrote the gospel of Luke. The Epistles, or the Letters, are mostly exactly that–a series of letters written by various teachers in this new Christian movement to other individuals or groups within it, teaching, consoling, admonishing and generally communicating big ideas that were growing out of an increasingly diverse Christian population, both Jewish and Gentile in origins.

Christian beliefs are incredibly diverse at this very early point in the faith, and that diversity is now representing itself in many forms of Christology. According to the Book of Acts, the Gospel spread out in concentric circles from Jerusalem to Judea, to Samaria to the ends of the earth. But in Acts, if it is read critically, one can see it that it did not really spread quite in that way. The message offered by Jesus and the disciples seemed to have been spread by people who heard it, who then went to their home villages and towns taking back the message as they understood it. There were anonymous followers of Jesus who went out of Jerusalem and they took their version of the message to different parts of the Roman world, including Africa and western Asia.

From Michael White of the University of Texas, Austin, we read this excellent description:

“One of the earliest indications that we have of the Jesus movement is what we tend to call “wandering charismatics,” traveling preachers and prophets, who go on saying the kingdom of heaven is at hand, continuing the legacy of Jesus’ own preaching, apparently. They travel around with no money and no extra clothes. So, they are supposed to perform miracles and heal the sick for free but they apparently begged for food. This is a different picture of the earliest form of the Jesus movement than what we’ve come to expect from the pages of the New Testament and yet, it’s within the tradition, itself. We hear even in Paul’s day that he encounters people who come from Judea, with a different kind of gospel message, and it looks like these are the same kind of wandering charismatics that we hear of, in the earlier stages of the movement, after Jesus’ death.

The Jesus movement is a sect. How do sects behave? One of the things they have to do is, they have to distance themselves from their dominant cultural environment. A sect always arises within a community with whom it shares a basic set of beliefs and yet, it needs to find some mechanism for differentiating itself. So, sectarian groups are always in tension with their environment. That tension is manifested in a variety of ways – controversies over belief and practice; different ideas of purity and piety. But, another manifestation of that tension is the tendency to want to spread the message out, to hit the road and convince others that the truth is real.” Michael White[1]

Eventually Paul and Barnabas take the message around the eastern Mediterranean, and Phillip goes to Samaria, and perhaps there is an Ethiopian eunuch in the Book of Acts who has converted, and he may take the Gospel back to Ethiopia. Somehow the message got to India and other places in Asia. So the spread of Christianity historically was much messier then it really is portrayed in that straightforward way written in parts of the New Testament.

Thomasine Christianity, which seems to have been very popular in eastern Syria and then all the way into India, is a form of Christianity that’s slightly different from the form of Christianity that was rising up in Rome at the time. There is another kind of Christianity that was growing up in Antioch and in western Syria, and there was yet another kind of Christianity that was likely growing up in Egypt and North Africa.

There were many small sects within Judaism at the time, with leaders promising all kinds of miracles, but those groups seemed to eventually fade, and have little to no traction among the people. So why did the early group eventually called Christians survive and thrive? It seems to have hinged on the fact that the followers firmly believed in something happening after the death of their leader, Jesus. Was it bodily resurrection? Was it some sort of motivation of the spirit, regardless of that death? Whatever actually happened, these early followers made extraordinary claims about Jesus–and the horrific thing that happened to him with that Roman humiliation of the man–this just showed the followers that what humans could do, God could undo. It was a powerful idea.

Clearly there are different geographical regions experiencing different kinds of Christianity, and those different kinds of Christianity are diverse in response to the Torah and the Jewish law. The form of Christianity that was predominantly Jewish was most likely in Jerusalem, led by James the brother of Jesus, who seems to have been famous for advocating a certain kind of law-observant, Torah-obedient form of discipleship to Jesus. Even away from Jerusalem, however, there is a form of Jewish Christianity that still seems to be keeping the law, and that is reflected in the Gospel of Matthew, with its teaching that the law is still something that people ought to obey.

The Gospel of Mark teaches a Christianity now predominantly Gentile, although it still has Jewish elements, but the people Mark writes for are people who are not keeping the law. They seem to believe that they do not actually have to keep the Jewish law.

Then the Christianity in Luke shows how the Torah, the law, represents a certain an ethnic tradition of the Jews. So if someone is Jewish they should keep the law but if someone is a Gentile, they do not need to keep the law.

In the Gospel of John there is almost no concern about the Torah law and tradition. Reading all through the Gospel of John, it is clear that disputes about any observation of Jewish law are not really at issue. There may be occasional questions about this from Jewish authorities, but it is not a focus of the gospel in any way.

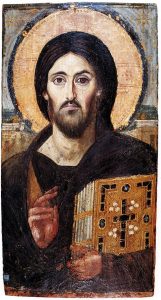

What really is at issue in all of the various place where the Jesus followers traveled, however, is Christology. What does each group believe about Jesus?

A quick summary of the different kinds of Christologies in early Christianity includes these:

- First is the gospel of Mark. According to Mark, Jesus is the Son of God, yet that Jesus is not necessarily completely divine or equal to God. He also considers Jesus to be the Messiah, the Christ, who has to suffer, and that Jesus’ suffering is for the purpose of ransoming sinners. Mark writes his Gospel is to convince his readers that Jesus’ suffering and execution was not an accident and it was not a catastrophe, and it was not a calamity, it was God’s will, it needed to happen. So the suffering Son of God is part of Mark’s Christology.

- Matthew’s Christology was a bit different. Here Jesus is presented as the long awaited Jewish messiah, the teacher, even as a new Moses. He is the most Jewish of the presentations of Jesus in the Bible, and the people reading Matthew see themselves as living the most Jewish of lives, which was a source of conflict at the time, shortly after the destruction of the temple. Jesus’ understanding and expanding of the Torah is key to Matthew’s Christology. Jesus is the fulfillment of prophecy, the Messiah.

- In Luke, this whole idea that Jesus’ death was a ransom is not there. In fact, Luke excises that part of Mark when he copied that part of Mark, and he leaves out that ransom passage from Mark because that doesn’t fit his Christology. In Luke we have the martyr prophet who serves as an example for Stephen, Paul, or any others who are followers of Jesus. Luke doesn’t have a doctrine of the atonement, the Christian doctrine that says, the death of Jesus was to pay for the sins of humanity or to redeem human beings from the debts of sin. Luke has Jesus dying to show people the way to God. Jesus’ martyrdom points that way.

- The Gospel of John contains the ideas closest to what will be seen as orthodox Christianity. According to John, Jesus is fully God, co-equal with the Father, he is “I am”, identifying himself with the figure who appeared to Moses in the burning bush, he’s the descending and ascending redeemer, he’s the lamb of God sacrificed for the people, and in his sacrifice he takes away the sins of the world. All those elements would end up becoming orthodox Christianity, and those can be found in the Gospel of John.

- And, of course, there are Christologies not represented in the 4 canonical gospels. Thomasine Christianity tends to see Jesus as a bringer of light, the bringer of knowledge concerning the kingdom of God, but not really in an salvific way, but instead as an example of what they can do, too.

- Gnosticism believed that Jesus was an incarnation of the divine who came to bring gnosis–esoteric knowledge of spiritual truth held by the ancient Gnostics to be essential to salvation–to people. It was self knowledge that gave a more thorough knowledge of God. Various forms and styles of Gnosticism existed, and Paul certainly wrote against some of their ideas in the epistles.

- Paul’s Christology seems to be a bit in flux, since it was not the primary concern of his letters, but he refers to Jesus as kurios–Lord or master, not theos-a god-, and so this places Paul right squarely within Jewish monotheism.

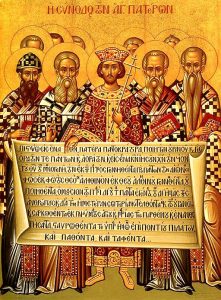

Years passed, and the struggle to understand the identify of Jesus continued. A lot of what became orthodox Christology was placed into writing at the Council of Nicaea. The Council of Nicaea took place in 325 CE, called together by the Emperor Constantine, who was tired of all the Christian squabbling, especially the arguments about Christology. Bishops and leaders came from around the empire in order to come to some kind of an agreement about various beliefs. They wrote what has come to be called the Nicene Creed.

The Nicene Creed talks about Jesus being “very God, from very God, God from God, light from light, begotten not made” because that was one of the main Christological ideas at the time. Was Jesus the Son of God because he was born from eternity as divine, or did God say at one point “I’m going to give him divinity status?” The Nicene Creed said that Jesus did not become divine, it states that Jesus always was divine.

So orthodox Christology was set to a great extent by the Nicene Creed in 325 CE, but between the year 30 CE, or so, when Jesus is crucified, to the 50s when Paul was writing his letters, to the year 70 CE when the Jerusalem temple is destroyed and the Gospel of Mark may have been published, to maybe a year in the 90s when the Gospel of John is written– from those times all the way to year 325 CE where there is a whole lot of fighting going on between Christians trying to solidify their ideas into universal belief for the church–how did the view that became Orthodox Christian belief evolve?

An interesting reality in very early Christianity–as early as 35 CE- might be reflected in this set of ideas:

From Helmut Koester’s[2] article accompanying the Frontline: From Jesus to Christ production:

“One interesting problem is simply the experience of diversity. We sometimes think that it’s just such a shame that we have so many Christian denominations and so many other religions all in one country. “Wouldn’t it be great if we have only one belief and one religion as it was in the time of the early Christians?”

No, it wasn’t [so] in the time of the early Christians. The early Christians had a hard time to discuss with each other, fight with each other to establish certain patterns and criteria for the organization of community, what was important in the churches. Was it indeed important that churches established mutual responsibility for each other and care for the poor as part of their dossier? This is what they’re supposed to do. And that discussion in our church was very helpful twelve years ago, when we discussed whether we should open a shelter for homeless people in the basement of our church.

But the other aspect is the diversity of religious movements. And that in fact early Christianity, by moving into different realms of the different universes of thought and of religion in the Greco-Roman world, adopted a lot of concepts from other religions, lots of them pagan religions, which enriched the early Christian movement tremendously.

Mainstream Christianity has always wanted to convey the idea that at the very beginning of the faith, during the time right after Jesus, that everyone was united, everything was clear, everything was understandable. Often modern preachers talk about this, and indicate that it was only gradually, under terrible outside influences, that heresies arose and conflict resulted, so that true believers must revert to that Golden Age, when everything was united and all people believed the same way about Jesus and who he was. But the reality is that there was never anything even vaguely like that so-called Golden Age of faith. Disagreements occurred right away, and the Epistles show this with quotes in various places about all the different preachers out there, and who would tell the people “the real truth” about belief.

There were fights about being Jewish first, about not having to be Jewish, about circumcision, about who Jesus was, about whether the death and resurrection was most important, or the teaching of Jesus was most important, or that Jesus as the fulfillment of prophecy was most important, or whether Jesus had actually died, or whether he was divine or not–it was very, very messy and divided from the very beginning.

And there can be some truth to the statement that the victors write the history! What is regarded now as heresy is just the sets of beliefs that ended up not being dominant in the history of squabbles. We have Gnostics. Marcions, Arians, Donatists, and many more whose ideas lost out to some others that became the accepted doctrine of Christianity.

Looking at the stories passed on, the ideas thought most important to the writer of Acts, but also to the writers of the various Epistles that went out to the early churches, helps all students of the Bible understand some of the earliest development of Christianity.

Attridge, Harold, et al. “The Diversity of Early Christianity | from Jesus to Christ – the First Christians | Frontline.” Frontline: From Jesus to Christ, Public Broadcasting Service, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/religion/first/diversity.html.

Turner, Geoffrey. “Pauline Christology: An Exegetical-Theological Study. By Gordon D. Fee.” Heythrop Journal, vol. 50, no. 1, 2009, pp. 147–148., https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2265.2009.00438_31.x.

May, Herbert G., et al. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha: Revised Standard Version, Containing the Second Edition of the New Testament and an Expanded Edition of the Apocrypha. Edited by Michael D Coogan, Oxford University Press, 2007.

Gabel, John B. The Bible as Literature: An Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2006.

White, Michael, and Helmut Koester. “The Story of the Storytellers – Importance of the Oral Tradition | from Jesus to Christ | Frontline.” Frontline: from Jesus to Christ, Public Broadcasting Service, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/religion/story/oral.html.

White, Michael, et al. “The Jesus Movement | from Jesus to Christ – the First Christians | Frontline.” Frontline: from Jesus to Christ, Public Broadcasting Service, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/religion/first/themovement.html.

Dale Martin, Introduction to the New Testament, Yale University: Open Yale Courses, http://oyc.yale.edu. License: Creative Commons BY-NC-SA . Most of the lectures and course material within Open Yale Courses are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 license. Unless explicitly set forth in the applicable Credits section of a lecture, third-party content is not covered under the Creative Commons license.