7 Voice Appropriation: A Deeper Look

Theodore Gracyk

Chapter Goals

- Define voice appropriation

- Explore racial stereotypes that use voice appropriation

- Explore the idea that voice appropriation is theft

- Define cumulative harm

- Understand the cumulative harm of voice appropriation

- Understand the persistence of some common racial stereotypes

- Understand how voice appropriation can generate dialogism

- Understand how dialogism can challenge racism

- Understand silencing in relation to voice appropriation

7.1. Voice Appropriation: Reviewing the Basics

This chapter goes into more detail about one kind of cultural appropriation. It examines voice appropriation and how it has supported racism in the United States. It also presents ways in which voice appropriation has been used to challenge the dominant culture.

Voice appropriation is sometimes treated as the same thing as cultural appropriation. However, this book has adopted the view that there are several other modes of cultural appropriation. Style and motif appropriation should not be equated with voice appropriation. (See Chapter 1, Section 1.6.) Therefore, the phrase “voice appropriation” is used in a narrower, more specific way than in some recent accounts of it.

Voice appropriation takes place when someone presents a second person’s thoughts or point of view, or when someone presents a representative or collective voice reflecting another culture’s point of view. To put it another way, voice appropriation is present when a communication claims to offer insight into another person, or into the worldview and belief system of another culture. Generally, but not always, the voice appropriation is presented in a way that makes it clear that it presents someone else’s point of view.

Understood in this way, voice appropriation is very common. For example, suppose someone recommends against vitamin C supplements by saying, “You shouldn’t take those vitamin C supplements. My doctor warned me that they can cause kidney stones.” Here, the voice appropriation is an appeal to the authority of the medical establishment. The speaker says that a representative of the medical profession has warned about a bad side effect. Like most voice appropriation, this one is probably selective. It is likely that the doctor had other things to say, but the speaker is only presenting things that favor the speaker’s own point of view. As this example suggests, one can sometimes tell that voice appropriation is present without knowing how accurate it is.

When someone presents the thoughts or point of view of someone in a different culture, the voice appropriation is also cultural appropriation. Unfortunately, this kind of appropriation always carries a high risk that the appropriated point of view will be misunderstood and misrepresented. It is likely to be filtered by the values and assumptions of the person who is creating or reporting that voice. So, voice appropriation should be approached with special caution when it is cultural appropriation. For example, a common Internet meme claims that the Chinese sage Confucius said “Before you embark on a journey of revenge, dig two graves.” He never said anything of the kind (Sun 2021).

One of the most questionable versions of voice appropriation can be difficult to identify. This is the case of cultural impersonation, where someone pretends to be a member of a culture but, in fact, is not a member of that culture.

For example, take the case of a married couple who identified themselves as Okah Tubbee and Laah Ceil Tubbee, of full-blooded Indigenous ancestry. They were not. Tubbee was really Warner McCary, a Black man who had escaped enslavement, and Ceil was Lucile Stanton, most likely of English ancestry. Yet they traveled throughout the United States in the 1840s and made a living from McCary’s performances of flute music that they claimed was Indigenous music. They also advertised him as “Dr. Okah Tubbee” and charged for supposedly Indigenous healing practices. Fearing that McCary would be returned to slavery after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, they emigrated to Canada, where their impersonation collapsed due to their ongoing medical malpractice (Hudson 2015). Their claim to know “Indian” medicine led to at least one charge of manslaughter. It is more difficult to say how much harm was done by their other misrepresentations of Choctaw culture. A similar, more recent case of identity fabrication is the award-winning children’s book The Education of Little Tree (1976). It was published as autobiography, telling of a boy’s upbringing with his Cherokee grandparents. It was later revealed that the book was a hoax, just like the supposed autobiography of Okah Tubbee.

Excerpt from A Sketch of the Life of Okah Tubbee (1852)

[Voice appropriation presented as an autobiography]

Then I call to mind the words of the wise man of my tribe, who blessed him and pronounced him long life and wisdom, to exceed even that of his ancestors; that his judgment should be highly prized by the people; and his company and counsel sought by the counselors of his tribe; that he should have wisdom to detect the false-hearted, and expose his wickedness, and a kind heart to relieve the oppressed; judgment to administer relief to the afflicted; that the beggar should not ask of him in vain for food, or the weary one for rest; this said he and still more. …

My brothers, be open to receive the lesser light [The Northern Star] … that it may guide thy feet through the dark vale of old age, wherein is no light. When the heart is loaded down with sorrow, and when the bleak mountains of death shall appear in thy path, trust thyself still to its guidance. Though its light be feeble, yet it is constant and unvarying, as the Great Spirit from whom all light proceeds, whether high above our heads or beneath our feet. By its light, thou canst ascend that difficult mountain where the bright beams of the summer’s sun, whose rays warmed thy youthful heart into greatness, shall burst full upon thy new sight, making thy heart which had grown cold through weariness, sing joyously with warm delight.

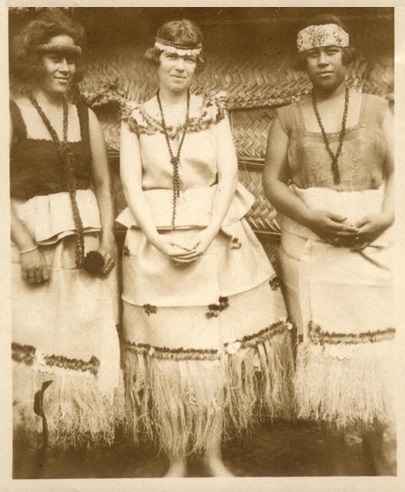

As with content appropriation, cultural appropriation of voice is sometimes done with good intentions. For example, it is often found in situations where the goal is to provide a factual report about a different culture. It occurs in scientific and news reports. After anthropologist Margaret Mead spent nine months in Samoa, she shocked Americans in 1928 by reporting that teens in that society engaged in (comparatively) high levels of premarital sex with multiple partners, and that teen girls in particular experienced no stress or shame relating to their sexuality and sexual activity (Mead 1928). (See figure 7.1.) As is often the case with highly original findings in social science, other anthropologists have questioned the accuracy of what Mead reported (Freeman 1983).

Level of accuracy is not directly relevant to whether something is or is not voice appropriation. What is relevant is that someone claims to be presenting beliefs and values of some other person or group. As explained in Chapter 1, a culture is an ongoing, inter-generational group that is organized around a set of shared values, behaviors, and beliefs that inform and guide their activities. (See Chapter 1, Section 1.5.) Therefore, any person’s attempt to explain or present a culture to which they do not belong will contain some level of voice appropriation, and it will also be cultural appropriation. The same is true when a particular person or fictional character is presented as acting on the basis of beliefs and values that are representative of another culture.

The focus of this book is appropriation in the arts. Artistic voice appropriation is not governed by the goals of truth and accuracy that are central to scientific and news reporting. Since around 1800, the arts have generally been valued as creative practices that emphasize originality and imagination more than accuracy (Eldridge 2014, pp. 135-41). Artists are often described as agents of “poetic truth,” which is a way of saying that audiences should expect the material to deviate from the truth if doing so makes it more interesting. It is no surprise, then, that voice appropriations in literature and other arts generally present an imaginary “other” in place of genuine culture (Said 1978). In general, people who learn about other cultures through art will not have a clear way to distinguish what is accurate from what is misrepresented.

Finally, there is often a racial element to voice appropriation. Sometimes, the belief system and values of a distinct people or ongoing group are attributed to their shared race, rather than their shared enculturation. When this happens, the appropriation is likely to be racist in its perspective. However, just like content appropriation, voice appropriation can also be used to challenge racism.

7.2. Voice Appropriation Rated “G”

The Walt Disney Company is one of the most popular and influential media companies in history. Some of the films they created are criticized for being racist or promoting harmful racial stereotypes. Here are four examples of voice appropriation that have been accused of having this problem.

Song of the South (1946) — This movie is set on a plantation in the South during the Reconstruction era. It has been criticized for perpetuating racist stereotypes and nostalgia for the era of segregation in the South. The main character, Uncle Remus, is portrayed as a happy-go-lucky emancipated slave who sings songs and tells stories to cute White children. The stories he tells were staples of African-American folk culture as part of their African heritage. Although the film contains an Oscar-winning song, the film has been removed from commercial release because it suggests that enslaved Black people could lead happy, carefree lives. The film is unlikely to ever be released to audiences again (Barnes 2019).

Dumbo (1941) — The movie has a scene featuring five black crows who speak in stereotypical Black accents and use jive slang from the time period: “Step aside, brother. What’s cooking ‘round here? … What’s fryin’, boy?” During the film’s animation process, the lead crow’s name was Jim Crow, which is a reference to the segregation laws that were enforced in the United States at the time. The name did not appear in the film itself, but it suggests something about how the animators and Cliff Edwards, a White voice actor, were expected to approach the character.

The Jungle Book (1967) — The portrayal of the monkeys in the movie, specifically King Louie, has been criticized for perpetuating racial stereotypes of Black Americans. King Louie speaks in a jive accent and sings a song called “I Wanna Be Like You,” implying that Black Americans do not want a distinctive identity and want to be just like the dominant culture.

Peter Pan (1953) — The depiction of an American Indigenous society in the movie, especially the song “What Makes the Red Man Red,” has been criticized for perpetuating sex-crazed stereotypes and for being culturally insensitive. This aspect of the film embraces colorism, the stereotype in which lighter-skinned members of an ethnic group are presented more favorably than dark-skinned ones. In this case, Peter Pan befriends Tiger Lily, an Indigenous girl whose skin color is notably lighter than everyone one else in her village. Other than her cries for help when captured and facing death, Tiger Lily never speaks. (See figure7.2.)

To their credit, when Disney+ provides streaming access to any of these films, they post a content warning about the offensive material. At the same time, “media exposure is associated in many ways with racial assumptions and beliefs of U.S. youth” (Ward and Bridgewater 2023). Content warnings are unlikely to cancel the impressions created by the material.

The wrong conclusion here would be that the Disney Company was historically worse than others. Their films are discussed because they confirm that racial stereotyping was common in children’s entertainment. When these films were made, rivals such as Warner Brothers studio, Universal Pictures, and Paramount Pictures were just as bad, and sometimes worse. Racist voice appropriation can be found in any modern society that seeks ongoing justification of its mistreatment of non-dominant groups. At the same time, the disappearance of openly racist material created as general entertainment does not mean that it is gone from American society. Voice appropriation of non-dominant groups is still very common, and much of it contributes to racism without being as blatantly insensitive in its stereotyping as these four examples.

7.3 Is Voice Appropriation Always Wrong?

Some people seem to hold the strict view that voice appropriation from other cultures is always wrong. On this view, we must always — without exception — let representatives of a culture speak for themselves. From this perspective, only members of a culture can and should speak for that culture. However, some strongly negative consequences will follow from adopting such a policy. To do so would, for example, stop the work of archaeologists who study and report on lost cultures. After all, there are no Etruscans and Noks any longer, so the only people who can tell us about their cultures are outsiders. Saying that cultural outsiders cannot speak about the beliefs and values of these “lost” cultures would mean no longer talking about them.

Strictly speaking, there are no Romans any more, either. Yet some of William Shakespeare’s plays are set in ancient Rome: Julius Caesar, Titus Andronicus, and Coriolanus. Any standard performance of them involves extensive voice appropriation. Should we stop performing them?

Similarly, the strict view — that voice appropriation involving other cultures is always wrong — would limit who can translate any text from one language to another. Avoiding voice appropriation would also mean that no one should use translated subtitles when watching a foreign film or television series unless they first verify that the translation was produced by a cultural insider. It also suggests that the common practice of dubbing a film into multiple languages is wrong when the dubbing uses the voice of a cultural outsider. Therefore, Daveigh Chase should not have agreed to provide the voice of the Japanese girl, Chihiro, in an English-dubbed version of Spirited Away (2002), and it is wrong for audiences to watch that version of the film. It might mean that Korean studios should not produce Korean-language versions of Japanese manga that relocate the stories from Tokyo to Seoul. It might even be taken to mean that only people who read Danish should have access to the Hans Christian Anderson story of “Den lille havfrue“ (the little mermaid), and it was wrong for the Disney Company to change a Danish-speaking mermaid to an English-speaking one. (See figure 7.3.)

To be fair to those who seem to condemn all cases of voice appropriation, it appears that some people condemn it because they define it more narrowly that traditional usage. They deny the possibility of voice appropriation by a non-dominant group. (See, for example, Baker 2018, p. 111.) For instance, K. Tempest Bradford says that “cultural appropriation is indefensible” (Bradford 2017) and does so by appeal to a definition of it as a “power dynamic in which members of a dominant culture take elements from a culture of people who have been systematically oppressed by that dominant group” (Johnson 2015). From this perspective, Koreans do not engage in cultural appropriation when they adapt Japanese manga, for Korea has not systematically oppressed Japan. Similarly, there is no plausible sense in which the United States has systematically oppressed Canada, so it would not be cultural appropriation for an American restaurant chain to promote poutine as an upgrade to French fries.

However, restricting the definition to cases inovolving a specific power dynamic deprives us of a standard, neutral way of talking about what is happening in a great deal of art and culture. Narrowing the definition in this manner tells us that there is appropriation if a member of the dominant culture shares a bogus quotation from the Chinese philosopher Confucius. However, it is not appropriaiton if the same quotation is then passed along by a Japanese-American or Cherokee friend. Drawing a line in this manner is needlessly confusing. Returning to an example introduced above, this definition tells us that Warner McCary did not engage in voice appropriation and cultural appropriation when he claimed to be Okah Tubbee. After all, McCary was not a member of the dominant culture. Yet it seems that McCary should be described as engaging in voice and cultural appropriation.

To put it another way, narrowing the definition to “indefensible” cases means we must determine who is oppressed, and by whom, before we classify anything as appropriation. Has the United States systematically dominated Korea? If not, then it’s not cultural appropriation for Americans to post themselves performing dance moves taken from K-pop groups on social media. Famously, Paul Simon traveled to South African to record with mbaqanga and isicathamiya musicians for the Graceland album (1986). The musicians themselves have praised him for creating worldwide commercial opportunities for their music, but some critics contend that Simon was operating like an oppressive colonialist. Do we have to settle this difference of judgment before we can describe what Simon did? However, if these two examples are not appropriation, what term describes them?

More urgently, equating voice and cultural appropriation with a specific power dynamic means that we must deny the possibility of successful allyship through the use of cultural appropriation. But if Winslow Homer was not engaged in cultural appropriation when he painted Dressing for the Carnival, what was he doing? (See figure 7.4, and see Chapter 6, Section 6.4.) A narrow, ethically-loaded definition also means that Song of the South and Dumbo cannot be put into a list of animated films involving cultural appropriation until after we prove that their voice appropriations from Black culture are wrongful. However, as will be explained later, Dumbo’s voice appropriation may be another case of successful allyship. Yet, clearly, the crow scene of Dumbo uses the same approach as many of the scenes in Song of the South. For these reasons, it is desirable to use the common, standard term to describe what is happening in these two cases: voice appropriation. Cultural appropriation, including voice appropriation, is so common that it remains useful to identify and label its presence before coming to a conclusion about how the two cultures relate and whether the particular case is exploitive or not.

Finally, it does not help to restrict the broad labels “voice appropriation” and “cultural appropriation” to the wrongful and exploitive cases unless they are all wrong in the same way. If we think that different cases are wrong for different reasons (Johnson 2015), then it is useful to retain a neutral label to indicate what they all have in common. Since we already have a long tradition of using “voice appropriation” and “cultural appropriation” to capture that idea, it is best to keep using them in the broad, neutral way. Minh-Ha T. Pham points out that English already contains a dedicated term for wrongful borrowings: plagiarism (Pham 2017). Unfortunately, Pham’s suggestion that we capture the issue of power dynamics by using the phrase “racial plagiarism” for wrongful appropriation has not been adopted.

One alternative to condemning all voice appropriation from other cultures is to approach it with an understanding of the difference between respectful and exploitive voice appropriation. The core issue is that some societies and cultures hold a dominant position relative to others. (See Chapter 2, Section 2.5.) As such, many things can go wrong with a dominant group’s appropriation from a non-dominant group.

Therefore, the approach taken here is to use the phrases “voice appropriation” and “cultural appropriation” in an ethically neutral way, as the name of a widespread cultural practice. Some cases are disrespectful, offensive, and wrong, but other cases are acceptable forms of cultural exchange.

7.4. Is Voice Appropriation a Kind of Theft?

Some writers suggest that wrongful appropriation is generally to be understood as a kind of theft. For example, in 1848 Frederick Douglas objected to the voice appropriation of minstrel shows by accusing them of stealing for commercial purposes:

[T]he “Virginia Minstrels,” “Christy’s Minstrels,” the “Ethiopian Serenaders,” [are among] the filthy scum of white society, who have stolen from us a complexion denied to them by nature, in which to make money, and pander to the corrupt taste of their white fellow-citizens. Those performers are undoubtedly in harmony with [a slave owner’s] refined and elegant taste … and awaken in his bosom a rapture only equalled by that celestial transport which thrills his noble heart on witnessing a TREMENDOUS SQUASH! (Douglas 1848, p. 2)

Douglas’ reference to stealing became a common idea in the 1960s and after. For example, Amiri Baraka complained of “The Great Music Robbery” within popular music. He condemned White musicians and music companies who copied Black music and then resold it as “White” creativity (Baraka 1987).

The charge of theft is certainly correct regarding a great deal of tangible appropriation. (See Chapter 1, Section 1.3.) However, a great deal of cultural appropriation is imitation that does not involve any tangible theft. In particular, voice appropriation seldom overlaps with tangible appropriation. The original seal of Massachusetts Bay Colony engaged in voice appropriation by putting the words “Come here and help us” into the mouth of a welcoming Indigenous man. (See Chapter 1, Figure 1.15.) Zane Grey engaged in voice appropriation when he created the character of Nophaie and then offered him as a representative of all American Indigenous people. (See Chapter 1, Section 1.7.) Minstrel shows were frequently presented as “authentic” presentations of Black culture. (See Chapter 4, Section 4.7.) These are acts of ventriloquism, that is, of voice projection.

Zane Grey did not take any physical property from Indigenous people. Physical property did not change hands when the Disney company portrayed the crows in Dumbo. Therefore, if there was theft, it would be theft of intellectual property.

On closer examination, it appears that nothing that resembles property — either intellectual or tangible — was appropriated in these two cases. New, original fictions were created. They drew on general background information and cultural stereotypes rather than identifiable intellectual property. However, general background information is never considered anyone’s exclusive property, and whatever is distinctively original in a fiction is the the property of its creator. But if no property is taken, then “theft” seems to be the wrong way to challenge what is happening here.

James O. Young makes the additional point that cultural appropriation can only count as theft if we change our emphasis from individual to collective ownership. To be theft, the material or content would have to be the property of the culture, that is, the group as a collective whole. If the material is merely from one individual, such as plagiarism of a specific song, then the wrongfulness is ordinary theft of intellectual property. It would be independent of the finding that there is cultural appropriation (Young 2010, p. 21). Young is spelling out a detail of the problem raised by Douglas and Baraka. They are less concerned about specific cases than with widespread practices of the dominant culture, including the general practice of motif and style appropriation.

Given this background, the most basic problem with treating voice appropriation as theft is that it only makes sense within a cultural system that defines and upholds the idea that culture is property, that is, that cultural heritage is cultural property. In other words, it is the view that a culture can have property rights in some general, widely shared information. However, different societies have very different ideas about what counts as tangible property and intellectual property. This idea does not seem to be a traditional belief of the non-dominant cultures at issue here. If anything, these cultures did not develop ideas about intellectual property until they encountered European property standards. As explained in Chapter 1, modern rules about intellectual property did not govern visual images in Japan until late in the 19th century. (See Chapter 1, Section 1.2.) In fact, the idea of intellectual property, such as ownership of any song or story, is a historically recent development. Basically, it is a European innovation of the 15th century. There are a handful of earlier examples, but they all cite personal creativity as the basis of the property rights (Moore and Himma 2022). Modern protections generally trace back to English law, most notably the Statute of Anne (1710) and its short-term protections for printers and booksellers. (See figure 7.5.)

Historically, there has been no recognition or protection of styles, motifs, and general information as the property of a specific society or cultural group. References to theft of musical style from Black culture simply do not align with the historical idea of intellectual property rights. These claims of theft are a metaphorical claim about wrongful appropriation, not a literal one. It is a way of saying that it is not legally prohibited behavior, but it should be.

Although it is a radical and new idea, the view that cultural heritage is cultural property has been gaining support. The goal of enforceable, collective property rights for some aspects of culture has become more common in the last 50 years. It has gained limited support in the United States. In 1990, the United States adopted the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. However, this approach is an extension of the traditional European/American approach. It also has the drawback that it imposes a uniform approach to the nature and rights of protected property. It is not sufficiently contextual, that is, it is not open to the idea that the Indigenous peoples of the United States are diverse in their traditions and views (Coombe 1993, pp. 270-71). A policy based on dominant-culture ideas about property ownership will not fit the traditions and situations every non-dominant group it attempts to cover. In other words, a solution that tries to establish uniform laws about collective intellectual property will be insensitive to cultural differences. Furthermore, in a society where wealth and access to legal processes continue to favor the dominant culture, property laws will provide limited protection for property claims of non-dominant groups (Feldman 2022). Consequently, saying that theft is the underlying problem of wrongful voice appropriation is a limited approach. It is unlikely to serve as an effective correction to the issue.

Audre Lorde, a Black feminist activist, coined the expression “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house” (Lorde 1981, p. 98). In relation to the current topic, Lorde’s message is that people should not expect social structures designed to protect the interests of a privileged group to serve the opposite purpose. Intellectual property laws are a structure of this type, and they are probably not going to provide a satisfying analysis or solution to the issue of voice appropriation.

7.5 Voice Appropriation Creates Cumulative Harm

As an alternative to the charge that theft is present in most wrongful appropriation, many analyses propose that different cases are wrong for many different reasons (Johnson 2015). This has a drawback. It suggests that we have no underlying reason to be suspicious of voice appropriation. Erich Matthes proposes a different approach. He looks for a more unified account of what is generally wrong and most objectionable about cultural appropriation of voice. His approach is consistent with there being multiple harms from appropriation, but it has the advantage of highlighting the most common one.

Setting the idea of theft to one side, Matthes begins by identifying three other challenges to voice appropriation when the dominant culture practices it.

Objections to cultural appropriation, especially from Native communities, have often appealed to the idea that appropriative acts can silence, speak for, and misrepresent [non-dominant] voices, a function predicated on a history of … oppression and its continuing effects and manifestations. (Matthes 2018, p. 1004)

Breaking these out, three kinds of voice appropriation are generally wrong:

-

- Ventriloquism/speaking for others

- Misrepresentation/stereotyping others

- Silencing others

Matthes asks what these have in common, and proposes that voice appropriation is wrong, when it is wrong, because it involves exploitation of cultural identity, not theft. It is wrong when a non-dominant group is the subject of the voice appropriation and someone in the dominant group exploits the very fact that the other group is routinely oppressed. It is wrong to participate in, and profit from, exploitation of others. Most seriously, voice appropriation from non-dominant groups “interacts with dominating systems so as to silence and speak for individuals who are already socially marginalized” (Matthes 2016, p. 349). Therefore, the mere social fact of ongoing racism tends to make it wrong to engage in voice appropriation from racially oppressed groups. (Concerning the proposal that it is a social fact, see Chapter 2, Section 2.4.)

It does not follow that it is always wrong to engage in voice appropriation from oppressed groups. However, it does put the burden of proof on those who engage in it. (Charges of theft or stealing have it the other way around, putting the burden of proof on the victims.) Voice appropriation from non-dominant groups is allowable only if doing so pushes back against the historical oppression faced by the relevant group. Sections 7.8 and 7.9 will suggest that there are allowable cases using this criterion.

As a method for identifying wrongful voice appropriation, this approach has the advantage that it does not demand evidence that a particular appropriation directly harms anyone. James O. Young is likely correct that there is not much harm from any specific act of appropriation (Young 2010, p. 113). However, the social fact of racism makes it wrong even if no one can point to specific harms to specific individuals. It is wrong in roughly the same way that it is wrong to toss a plastic bottle in the ocean even if one knows that the effects of that one action are minimal. Individual actions of polluting the ocean or dumping harmful chemicals into the watershed are not excusable on the grounds that things are already bad that it will make no measurable difference. The same point holds for wrongful appropriation.

Consequently, when voice appropriation is wrong, it is generally wrong because it contributes to an ongoing pattern of cultural domination. When this connects to a pattern of racial distinctions, it also contributes to the social fact of racism. According to Matthes, the troubling contribution is promotion of a social environment that is “indifferent” to truth (Morreall 2009, p. 106). Indifference to the truth is, after all, one of the bedrocks of the social fact of racism. (See Chapter 2, Section 2.2.)

Generally speaking, members of a dominant social group will give more credibility or trust to communications created and shared by members of the dominant culture than to ones coming from non-dominant groups. If the dominant culture misrepresents other groups, the misrepresentations will generally be accepted as facts. Lee Francis IV, Executive Director of Wordcraft Circle of Native Writers and Storytellers, warns that “the American story is one in which history and fiction are woven together, often at the expense of marginalized groups” (Francis 2023, p. 3).

Seen in this way, the wrong is not simply a matter of negative stereotypes. For example, the dominant culture promotes the story that an Indigenous girl named Pocahontas was 20 years old and saved a nice man named John Smith and fell in love with him. (See figure 7.6.) Because the dominant culture keeps repeating this story, children “buy” — both metaphorically and literally — the misrepresentations of the animated film Pocahontas (1995). Although there is nothing overtly negative about the Pocahontas myth, children are primed to ignore the Indigenous voices who protest that she was a pre-adolescent child at the time, that Smith was a brutal mercenary who didn’t need saving, and that she never had that kind of relationship with him (Lewis 2021). Overwhelmingly, a fictional story that serves the interests of the dominant culture is the one that is repeated and accepted by members of the dominant culture. (Do an Internet search of the phrase “Pocahontas saves Smith” and see which images are provided. How old is she?) Notice, also, that this specific portrayal of the story (figure 7.6) shows her tribe as living in tipis, reinforcing the myth that this was standard in Indigenous societies. However, it is not accurate concerning the Powhatan tribe. Although the tipi is not necessarily a negative stereotype, it is yet another way in which this picture contributes to the dominant culture’s indifference to truth concerning other groups and cultures. (For more on the negative implications of placing tipis in this scene, see Chapter 5, Section 5.5.)

The problem is not simply that most members of the dominant culture put greater trust in communications emerging from their own culture. When a story or image becomes popular, it also becomes more likely that members of the non-dominate culture will only know the version produced by the dominant culture. In the same way that English has gradually eradicated many of the world’s Indigenous languages, the stories and images of the dominant culture can reduce the sharing of others, driving alternative voices out of circulation. (This is one of the ways that voice appropriation is an act of silencing.) Alice Walker has written that that she directly experienced how Disney’s Song of the South changed her relationship to traditional Black folklore, so that “the stories themselves, which, passed into the context of white people’s creation, I perceived as meaningless. So there I was, at an early age, separated from my own folk culture by an invention.” She became “ashamed” of this part of her culture (Walker 1981, p. 31). In other cases, members of non-dominant groups may end up assigning more credibility to the dominant culture than to voices within their own culture. “When a young Indian child roots for the cowboys something’s wrong with this picture,” explains Sonny Skyhawk (Dutka 1995).

In summary, the harm of voice appropriation is systemic. It has to be approached as the cumulative harm that emerges from “constantly being represented, but never listened to” (Coombe 1993, p. 279). The harm is due to the ongoing repetition of certain representations of a particular culture, and to everyone’s ongoing exposure to that repetition. In this respect, it is like pollution and many poisons. Most people will suffer no clear harm from one exposure to lead or arsenic, but repeated exposure is very harmful, to the point of being deadly. The same is true of most forms of pollution. Tossing one plastic bottle into the ocean won’t cause any measurable harm. However, the gradual build-up of plastics in the ocean is having a terrible environmental effect, disrupting food chains and threatening many species with extinction, including ones that humans desire as food. Even if no one person or action can be blamed for any of the cumulative harm, it is real. The harm of misleading voice appropriation works in a parallel fashion.

Even if no one is directly harmed by false stories about Pocahontas or Southern plantation life, the repetition of voice appropriation hurts non-dominant groups. It erodes their culture. There are other harms, as well: economic, social, even health. The evidence is now clear that the standard American diet, loaded with the saturated fats in meat, explains the level of heart disease in the United States. In the same way, the constant presence of racism in American media contributes to chronic stress and many associated health problems in non-dominant groups (William 2018).

7.6. Deceptively Positive Stereotypes

These concerns about voice appropriation are not restricted to openly negative stereotypes promoted by the dominant culture. As Amiri Baraka observes about a common stereotype, “The disparaging ‘all you folks got rhythm’ is no less a stereotype, simply because it is proposed as positive trait.” By narrowing the range of achievement available for members of the Black community, the idea of natural rhythm remains a “Jim Crow attitude” (Jones 1963, p. 16).

Given this criticism, consider the The Help, a recent popular book and film about the Southern tradition of Black women as domestic workers for White families. In this case, the associated stereotype is that Black women are the best cooks and household help. This stereotype used to be very common in American culture, and it was linked to the idea that Black women would happily devote themselves to their White employers, especially their children. (See Figure 7.7.) This stereotype is superficially positive because it is the opposite of the negative stereotype that was promoted about Irish Immigrants as emotionally unfit for such work. (See Chapter 6, Section 6.6). The mammy stereotype promoted the idea that it was natural for Black women to support White domestic life, while at the same time pretending that mammies occupied a domestic role “where racial barriers do not hold sway” (St. John 2001, p. 144). By repeatedly portraying Black domestic workers as happy, devoted employees, the “mammy” figure reassured the White dominant culture that Black employees accepted their subordination.

In what is likely the best-known and most influential example, the 1939 film Gone with the Wind features a nameless Black woman who is only known as “Mammy.” Extending the stereotype found in the staged photograph “Please Mammy,” Gone with the Wind stresses that the large Black woman has raised the small, fragile White girl and then serves as her mother figure in adult life. Mammy, in return, hates the “Yankees” and does not question the social system that enslaves her. She does not want freedom for enslaved Black people if it means that her White enslaver will lose her plantation and wealth. Mammy describes emancipated slaves who support Reconstruction as “trash.”

The Help portrays the lives of Black domestic workers in Jackson, Mississippi, during two pivotal years of the Civil Rights Movement of the early 1960s. It updates the mammy stereotype by showing that Black domestic workers were frequently mistreated. The book also became a highly successful movie. It features Emma Stone as the young White woman whose growing awareness of discrimination frames the story. The book was adapted for the screen by a White screenwriter, so once again the dialogue spoken by Black characters is voice appropriation. Looking back at her role as one of the “help,” actress Viola Davis thinks it was a mistake to appear as the leading Black character: “have I ever done roles that I’ve regretted? I have, and The Help is on that list. … I just felt that at the end of the day that it wasn’t the voices of the maids that were heard” (Murphy 2018).

Ida E. Jones expands on Davis’ concerns about voice appropriation in The Help. The issue is that, yet again, White authorship filters the experience through a dominant culture perspective. Again, the issue is silencing more than misrepresentation. As Jones puts it, “This [story] has been told. We have books on this. We have articles. We have oral histories. … African-American women have been writing about this. And they they’ve never made this level of splash. So therein lies another, once again, market issue of how stories are marketed and packaged and sold. … how do we get our stories told from our perspective? Not to negate or silence hers, but on par.” (Quoted in NPR 2011.)

In other words, it’s not just what you see onscreen. The Help (the book) was written by a member of the dominant culture who didn’t actually know much about the lives of the maid, and then the screenplay was adapted and the film directed by another member of the dominant culture. Why aren’t Black creative people telling their own story in more films about Black lives? In this day and age, this isn’t really allyship anymore. The dominant culture still controls most stories about non-dominant groups instead of letting them speak for themselves. (For an idea of what critics want you to watch instead, see the recent films Fruitvale Station, Moonlight, The Sentence, Mosquita y Mari, and Frybread Face and Me.)

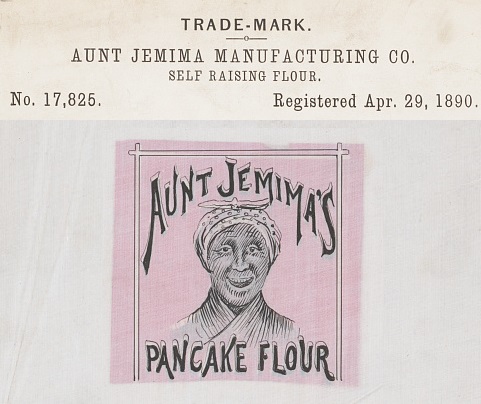

Although The Help tried to use the mammy stereotype to criticize segregation, the stereotype is part of a long tradition of celebrating the plantation culture of the South. One of the most notable examples is the creation, in 1889, of the fictional “Aunt Jemima” as a promotional trademark for packaged pancake mix. (See figure 7.8.) The name originated in a popular minstrel show song, “Old Aunt Jemima.” Like many other minstrel songs, it was performed with different lyrics by different minstrel companies. Although the song only appeared in minstrel shows after the Civil War, one version contains the following verse (Toll 1974, p. 260). Sung by a white man in Blackface who was dressed as a woman in an apron and headscarf, the performance invited White audiences to laugh at how the White “missus” gave false hope to her enslaved cook:

My old missus promise me,

Old Aunt Jemima, oh! oh! oh!

When she died she’d set me free,

Old Aunt Jemima, oh! oh! oh!

She lived so long her head got bald,

Old Aunt Jemima, oh! oh! oh!

She swore she would not die at all,

Old Aunt Jemima, oh! oh! oh!

Beginning in 1893, the company that sold the pancake mix went so far as to hire a Black woman, Nancy Green, to make public appearances as Aunt Jemima. Dressed like the woman in the advertising image, Green cooked pancakes in public to promote the product. Singing plantation songs and telling happy stories about Southern life while she cooked, Green gave thousands of public appearances before her death in 1923. Her personal appearances were so popular that the product was advertised with the slogan “I’se in town honey!” (See figure 7.9.)

During the same time period, the product was continually associated with slavery and plantations. In one magazine advertisement in 1920, the company promoted the fiction that Aunt Jemima was a “mammy” who lived in a log cabin on a plantation in Louisiana. They claimed that they purchased her secret recipe because it was praised by a Confederate general and implied — but did not directly say — that the general was Robert E. Lee. According to the story, Aunt Jemima personally cooked her special-recipe pancakes for him during the war, and then again 20 years after her emancipation from slavery. The story is structured to suggest that Aunt Jemima supported the Confederate cause during the Civil War. Other print advertisements praised the product’s “old-time plantation flavor” and had an Aunt Jemima figure speaking in dialect: “Here’s a temptilatin’ lunch chilluns love” and “Every bite is happifyin’ light.” Like Gone with the Wind, Aunt Jemima Pancake Flour promoted racist nostalgia by keeping a racist stereotype alive well into the 20th century.

7.7 Stereotypes Created for Children

Voice appropriations created for an audience of children are especially worrisome for the way they encourage indifference to truth. Implanting a misrepresented “voice” in children’s minds, these appropriations override communications by real participants in the non-dominant groups they stereotype. Because both humor and children’s animation are highly dependent on simplified stereotypes, children’s animation can be an especially harmful platform for voice appropriation.

The larger concern is that adults who have been exposed to specific stereotypes during childhood are more likely to be swayed by them when they are repeated later by respected voices in the dominant group. For example, the location of the Mexican-American border was one of the core issues that led to the formation and promotion of the 19th-century doctrine of Manifest Destiny. (See Chapter 4, Section 4.6). In 2015, Donald Trump launched his first run for the presidency with overtly racist appeals to the question of the border. Specifically, Trump tapped into stereotypes that developed after the U.S. seized large parts of northern Mexico. These stereotypes have portrayed Mexican Hispanics as racially undesirable people and therefore not welcome as immigrants.

If the meaning of the category of Mexican Hispanic is not immediately clear, it expresses the point that most Hispanics do not live in or originate in Mexico. Furthermore, because Mexico has its own Indigenous populations who have remained ethnically and culturally distinct within that country, not all people in Mexico should be identified as Hispanic. However, Mexican Hispanics are the focus here because they form the largest “minority” group in the United States. (See Chapter 2, Section 2.6.c.)

The primary stereotype is easily summarized. Mexican Hispanics are frequently portrayed as racially inclined to be lazy and “hot-blooded” or overly fixated on sex. Within the logic of this stereotype, they therefore avoid genuine work and tend to be thieves, drug dealers, and other sorts of criminals. They like to party and abuse alcohol and drugs. (This summary aligns with Roman 2000.) Christine Bold summarizes the stereotype in two words: “lustful degenerates” (Bold 1996, p. 28).

In this context, consider the power of appeals to this stereotype among voters born at the tail end of the “Baby Boom.” Most voters in this age group encountered this stereotype in children’s animation when they were children, in the 1960s. Specifically, Fritos Brand corn chips created a cartoon character in 1967, the Frito Bandito. Wearing a sombrero hat and armed with two six-shooters, the “bandit” appeared regularly in television commercials, often during children’s programming. In an act of voice appropriation, he sang an adapted version of a traditional Mexican song. Using a stereotyped accent, he sang, “I want Fritos corn chips. I’ll steal them from you” (Dingus 1986, p. 187). Following vigorous complaints from Hispanic groups in the United States, these lyrics were replaced so that he no longer spoke directly of stealing. The character’s appearance also softened. In one commercial, he simply takes a bag and puts it under his hat, indicating that he’s stealing it. In another, he offers to pay with “lead” (i.e., bullets) if the person with the chips doesn’t want to sell them. Although the advertisements were entertaining and fun, that does not excuse their use of voice appropriation. For that very reason, they may create an especially powerful association between theft and Mexican Americans for children.

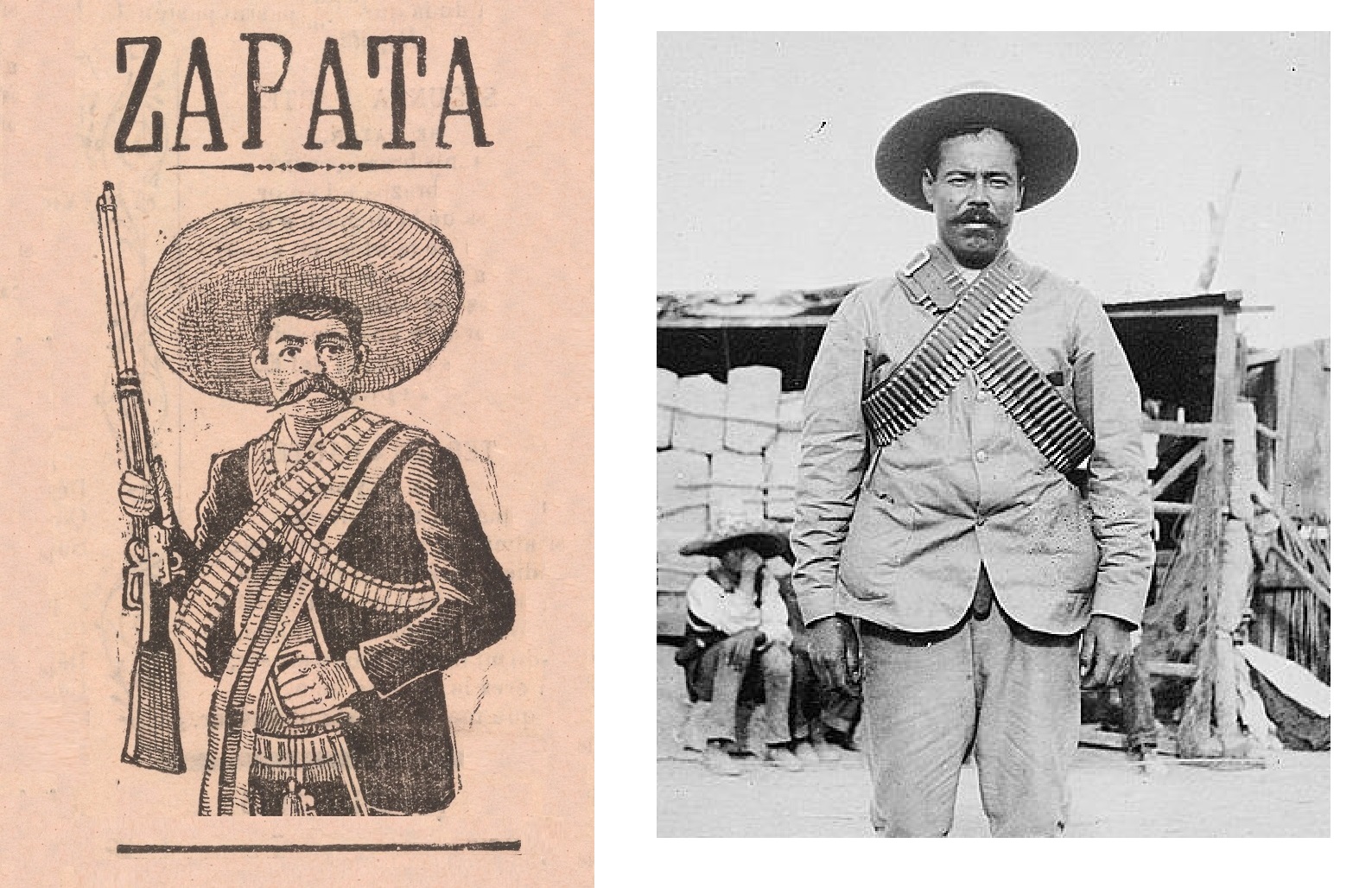

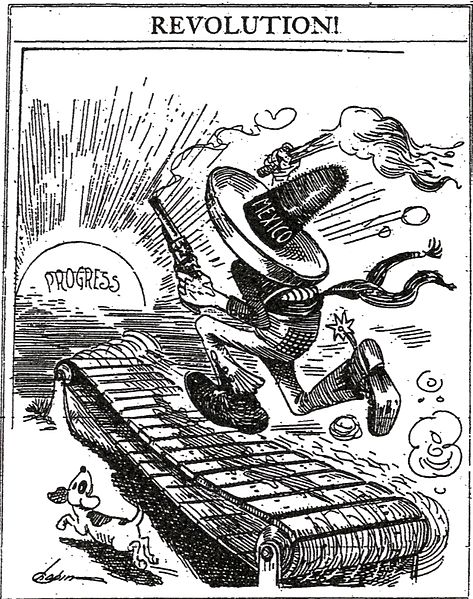

There is another layer of complexity with this particular voice appropriation. It is not original. It is a cartoon version of a negative stereotype that has been commonly presented throughout the 20th century. In this sense, the Frito Bandito furnishes children with a template, priming them to endorse subsequent exposures that are more overtly racist. Typical features of the stereotype are a large sombrero, one or more guns, and crossed bandoliers (bullet belts) across the chest. Frito Bandito has all of these features. As a result, he is simply a cartoon version of stereotype associated most directly with the Mexican Revolution of 1919-1920 and the violent years leading to it. His mustache, crossed bandoliers, and sombrero seem to have been lifted from widely-circulated images of Zapata (Emiliano Zapata Salazar) and “Pancho” Villa (José Doroteo Arango Arámbula). (See figures 7.10 and 7.11.)

Villa and Zapata were allies who conducted brutal guerrilla warfare during the Revolution, which is perhaps better described as a civil war. Although the United States initially backed their cause, President Woodrow Wilson changed the country’s policy, supporting a different faction in the conflict. When Villa crossed the American border in a bloody raid, Wilson sent 6,000 American troops into Mexico to find him. By then, his image and story were already famous in the United States. There had already been many reports in newspapers, and a 1914 documentary film about his exploits was popular in the United States. Wilson’s military action made him even more famous. Villa had been a bandit before he was a political leader and guerilla. After the United States turned against him, he was often dismissed as a mere bandit. As a result, his image became a prototype for the stereotypical Mexican bandit, strongly associated with robbery and killing.

However, a Villa-like stereotype had emerged even before Villa was prominently featured in the U.S. press in 1914 and after. As early as February 1913, a gun-wielding, sombrero-wearing bandit was featured as a stand-in for all of Mexican culture. (See figure 7.12.) As Mark Anderson explains about this political cartoon, it is pessimistic about the looming Mexican Revolution. It tells us that Mexicans cannot make “progress … until they willingly give up their lust for violence (the pistol) and anarchy (the torch)” (Anderson 1997, p. 30).

Anderson points out that such images were part of a larger campaign to solidify the stereotype that Mexican Hispanics are held back by the “inherent laziness, savagery, and lack of purpose of the half-breed” (New York Times, quoted in Anderson 1997, p. 67). Although photographs of Zapata and Villa may have served as the source of countless later appropriations, the connection between banditry and race was already in place.

Why did this connection arise? A major source was voice appropriation in popular stories and stage productions. Whether set in Mexico or the United States, stories about Mexican bandits were common in dime novels — cheap, mass market paperbacks produced between roughly 1860 and 1920. They were a staple of stories about the frontier within the vast territory seized from Mexico in 1848. Jamie Javier Rodríguez explains that the underlying message was that, as a people, Mexican Hispanics were naturally resistant to civilization and good government. Connecting these stereotypes with banditry provided additional justification of American expansionism (Rodríguez 2010, p. 106).

For example, The Girl of the Golden West was a popular stage play that had many performances between 1904 and 1908. In 1911, the author generated a novel from the play’s script. (The play, novel, and its various adaptations also contain racist voice appropriation involving Indigenous servants. However, the focus here is the tradition of voice appropriation of Mexican Hispanics.) The story is set in California during the gold rush. Newly-arrived Americans are already the dominant class, controlling all major businesses and upholding the law with lynchings. In the first chapter, the primary male character is introduced as “Mexican,” and there are allusions to his laziness, recklessness, and sexual attraction. Half-way into the story, his identity as a notorious bandit is revealed, and he explains that robbing people is “in the blood.”

Excerpt from The Girl of the Golden West, by David Belasco

The young man’s face clouded with disappointment. For two hundred yards or more he spoke not a word, though he spurred his horse in order to keep up with the now fast-moving stage[coach]. Then, all of a sudden, as the silence between them was beginning to grow embarrassing, the Girl made out the figure of a man on horseback a short distance ahead, and uttered an exclamation of surprise. The stranger followed the direction of the Girl’s eyes and, almost instantly, it was borne in upon them that the horseman awaited their coming. The Girl turned to speak, but the tender, sorrowful expression that she saw on the young man’s face kept her silent.

“That is one of my father’s men,” he said, somewhat solemnly. “His presence here may mean that I must leave you. The road to our ranch begins there. I fear that something may be wrong.”

The Girl shot him a look of sympathetic inquiry, though she said nothing. To tell the truth, the first thought that entered her mind at his words was one of concern that their companionship was likely to cease abruptly. During the silence that preceded his outspoken premonition of trouble, she had been studying him closely. She found herself admiring his aquiline features, his olive-coloured skin with its healthful pallor, the lazy, black Spanish eyes behind which, however tranquil they generally were, it was easy for her to discern, when he smiled, that reckless and indomitable spirit which appeals to women all the world over. …

[The man is Ramerrez. He is Mexican Hispanic, and a bandit who robs gold miners. They meet again, six months later, in a mining town. The Girl learns that he is an outlaw. He gives her the following explanation.]

“One word only—only a word and I’m not going to say anything in defence of myself. For it’s all true—everything is true except that I would have stolen from you. I am called Ramerrez; I have robbed; I am a road agent—an outlaw by profession. Yes, I’m all that—and my father was that before me. I was brought up, educated, thrived on thieves’ money, I suppose, but until six months ago when my father died, I did not know it. I lived much in Monterey—I lived there as a gentleman. When we met that day I wasn’t the thing I am to-day. I only learned the truth when my father died and left me with a rancho and a band of thieves—nothing else—nothing for us all, and I—but what’s the good of going into it—the circumstances. You wouldn’t understand if I did. I was my father’s son; I have no excuse; I guess, perhaps, it was in me—in the blood. Anyhow, I took to the road, and I didn’t mind it much after the first time. But I drew the line at killing—I wouldn’t have that. That’s the man that I am, the blackguard that I am. But—” here he raised his eyes and said with a voice that was charged with feeling—”I swear to you that from the moment I kissed you to-night I meant to change, I meant to—”

Until recently, only White actors played the role of Ramerrez on stage. This was also the case in the four early films made from the story. There is a point in the story where Ramerrez kisses her. The dominant culture could accept their physical intimacy in a written story, but they could not accept a display of real contact between a White actress and non-White actor. (The first interracial kiss in an American film did not occur until 1957.)

After establishing that Ramerrez is a thief due to his “blood,” the thrust of the story is that he is saved from his life of crime by the love of a White woman. This story is a reversal of the common Western plot that has the man rescue the woman. In The Girl of the Golden West , the racial element preserves the standard blueprint of having the dominant figure rescue the subordinate one. Understanding this couple as representative figures of different races, the story becomes a metaphor for the doctrine of Manifest Destiny. By having the White American rescue the Hispanic Mexican, American values and culture are portrayed as the remedy for the inherited flaws of Mexican Hispanics. However, the story is set during the transition phase as Americans are taking charge of Mexican land they have only recently seized. Therefore, the setting is the American West of “class distinction, ethnic and racial tension, economic destitution … and injustice” (Leppert 2009, p. 138). The lovers can only remain together by running away together. At the end of the story, their fate is left undetermined. In this manner, the story avoids showing and endorsing mixed-race marriage.

This story has enjoyed an enduring popularity due its adaptation as Giacomo Puccini’s opera, La fanciulla del West (1910). (See figure 7.13.) The opera is a cultural appropriation that translates the story into Italian. Puccini preserved the original story’s racist voice appropriations. Exoticism was exploited in many of Puccini’s operas, and for opera-goers in Europe and the eastern United States, “the Wild West” was as exotic as the Far East. (See also Chapter 1, Section 1.8.) Thanks to Puccini’s continuing worldwide popularity, the voice appropriation of The Girl of the Golden West continues to be staged regularly throughout the world.

Although real-world impact is hard to measure, content and voice appropriation featuring the bandit stereotype continue to play a role in American culture. Ito Romo proposes that there is a fairly direct line from the voice appropriation of the Frito Bandito to the appeal of Trump’s negative stereotyping of Mexican Hispanics (Romo 2018). They are simply two more versions of a stereotype that dates back to the American land grab of 1848. The Frito Bandito was a cartoon variation on a long-standing theme, notable only because it encouraged small children to accept it. Many of the children who sang along with the Frito Bandito responded to Trump’s appeals to the bandit stereotype. Trump promised to be “a new sheriff in town,” but one committed to perpetuating the policies of the 19th century (Romo 2018).

7.8. Stereotypes: A Second Look

Chapter 6 presented cases of content appropriation involving Black culture that worked against negative stereotypes. (See Chapter 6, Sections 6.4, 6.5, and 6.9.) These examples illustrate that cultural appropriation is sometimes a tool for confronting racism. What about voice appropriation? Are there cases of voice appropriation representing non-dominant groups that challenge society’s racist traditions? Earlier, it was suggested that The Help attempts do so, but fails. This section considers two examples of voice appropriation that look more promising.

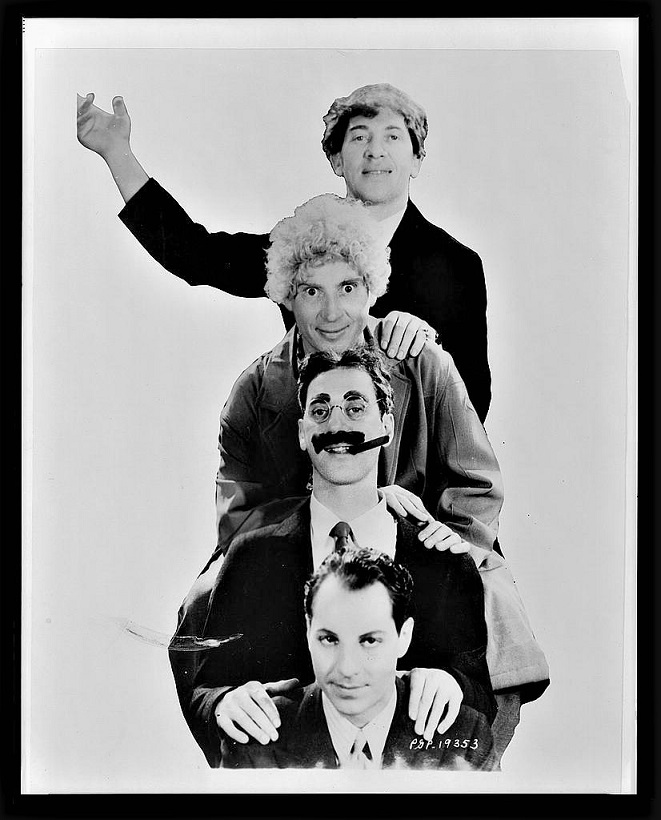

Consider the 14 films of the Marx Brothers. (See figure 7.14.) A comedy team of actual brothers, they were first generation German-Jewish. They developed a stage act based on voice appropriation, employing White ethnic stereotypes. (See Chapter 2, Section 2.6.f.) After they became Broadway stars, they transitioned to motion pictures. They were so popular in the 1930s that, for a time, people gave costume parties in which every guest was expected to show up as one of the four brothers, that is, as one of the four stereotyped characters. Many of the country’s most famous comedy writers and song writers wrote material for their Broadway shows and films. Like the brothers, these writers were White ethnic immigrants or first-generation Americans.

Audiences of the early 20th century recognized the White ethnic stereotypes of three of the brothers. Chico Marx always played the part of an Italian immigrant, with a matching accent. Harpo never spoke onscreen, and so had no accent, but his curly red wig announced that he was an Irish immigrant. Prior to World War I, Groucho played a German immigrant, with matching accent. The war brought about a wave of anti-German sentiment, so he switched accents by exaggerating his New York Jewish roots. (Comparisons between the films and later television interviews confirm that the voice used in the films is “staged” and not his normal accent.) Occasionally, he confirmed the Jewish connection with a Yiddish word, such as “schnorrer” (beggar) in Animal Crackers (1930). Zeppo appeared as an ordinary White American, a member of the dominant culture. (The exception is Horse Feathers (1932), where he plays Groucho’s completely assimilated son.) Basically, he played the “straight man” who set up jokes for the others. He does not appear in films after their fifth, Duck Soup (1933).

The comedy of the Marx brothers can be summed up in a famous line that Groucho wrote in a letter to an upper-class country club that offered him membership: “I do not wish to belong to any club that would have me as a member” (Marx and Fisher 1981, p. 36). The core plot of most of their films is that a group of White ethnic immigrants is thrown together in their shared pursuit of the money and other advantages of a social institution of the dominant culture. Then they tear apart that social institution. Much of the humor is based on misunderstandings based on language confusions and their lack of full assimilation (Wolfe 2011). They engage with a resort hotel and real estate boom in Florida (The Cocoanuts), a society party (Animal Crackers), the first-class passengers of an ocean liner (Monkey Business), a college and its involvement in college football (Horse Feathers), government (Duck Soup), the opera (A Night at the Opera), and horse racing and the medical profession (A Day at the Races). They also parody other films, as when Go West (1940) copies and then ridicules the Hollywood conventions of cowboy movies. Challenging the restrictions of the dominant culture, their characters push back and disrupt (and in some cases partially destroy) the American institutions they sought to join. They try their best, but Groucho, Chico, and Harpo are always outsiders in relation to the dominant culture. They often conclude that the dominant culture is not worth joining unless it is reformed. As one critic summarizes their importance: “The films are a serious and biting condemnation of American culture” (Gardner 2009, p. 1).

The humor of the Marx Brothers emphasized the outsider status of immigrants whose ethnicity was not yet clearly accepted as White: “the pervasive themes of trespass and belonging, of pretense and legitimacy reflect immigrant anxieties about acceptance into American society and ambivalence towards the costs and rewards of assimilation” (Lieberfled and Sanders 1995, p. 103). They films assumed that the audience knew the common stereotypes for various ethnic groups, and they played them up and exaggerated them. In this way, they employed reverse appropriation. (See Chapter 6, Section 6.7.)

The Marx Brothers often focused on the social breakdowns that occur between groups who misunderstand each other. Frequently, they played upon literal miscommunications, as in one famous scene in their first film The Cocoanuts. Chico plays a character with limited English skills:

Groucho — Now, here is a little peninsula, and here is a viaduct leading over to the mainland.

Chico — Why a duck?

Groucho — I’m alright, how are you? I say, here is a little peninsula, and here is a viaduct leading over to the mainland.

Chico — Alright, why a duck?

Groucho — I’m not playing “Ask Me Another,” I say that’s a viaduct.

Chico — Alright! Why a duck? Why that … why a duck? Why a no chicken?

Groucho — Well, I don’t know why a no chicken; I’m a stranger here myself.

In two of the films, Monkey Business and A Night at the Opera, their characters are stowaway immigrants. Both films have sequences on an ocean liner as they make their way to New York. In the former, they are penniless stowaways, and all four try to use the same stolen passport to sneak into the United States. In the latter, they hide in the small cabin room of a friend, and anarchy results as their activity overflows the room and spills out into the hallway.

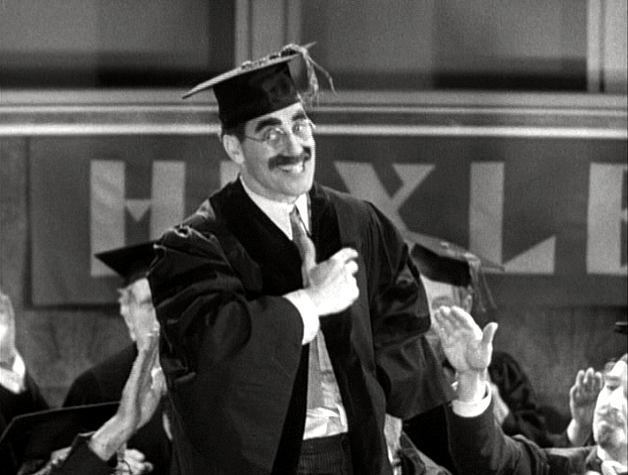

Groucho is sometimes placed in a position of authority, dominant in relation to Chico and Harpo. He then behaves in a way that makes existing institutions look arbitrary, oppressive, and ridiculous. Conducting a job interview with Chico in Duck Soup, Groucho asks job-seeking Chico this question: “Now what is it that has four pairs of pants, lives in Philadelphia, and it never rains but it pours?” Obviously, there is no right answer, suggesting that, for the White ethnic immigrant, there never is. So, Chico resists, turning it around by answering, “Atsa good one. I give you three guesses.” In Horse Feathers, Groucho ridicules his own power within the dominant culture. Responding to a suggestion that he should reform the college he runs, he launches into a song, “Whatever it is, I’m against it!” (See figure 7.15.) This turns into a parody of the dance numbers of Hollywood musicals. Robed faculty members sloppily imitate dancing chorus girls and then Groucho literally pulls each of their beards, a traditional sign of insult. As frequently happens with the Marx Brothers, a serious or important social occasion is disrupted and gradually collapses, emphasizing the fragility of the dominant culture’s institutional power.

In exploiting stock characters, the Marx Brothers were masters of voice appropriation from earlier voice appropriation. They expected their audience to understand that they were exaggerating existing theatrical stereotypes. As such, they were social critics, constantly challenging the dominant culture. It is true that there are lapses where racial stereotypes appear solely for the sake of a quick joke. However, there also seem to be cases where they introduce a racial stereotype in order to make fun of that stereotype, challenging its appearance. In some cases, it can be difficult to say if this is what they hope to achieve. In The Big Store (1941), a department store has a sale on beds. Caught there, where they don’t belong, they imitate salesmen. A stereotyped Italian couple with eight children arrives. (The wife speaks no English.) This sets up an escalation of stereotyping: they are followed by a family in stereotypical Asian clothing, who are followed by an Indigenous family, identified as such by their moccasins, fringed buckskins, and feather headdresses. This family is so out of place — what are these stereotypes from the 19th century doing in a New York City department store? — that it is plausible that the the visual joke is trying to raise that very question. Perhaps the point is to make the viewer aware that the parade of stereotypes is just that and nothing more: these are stereotypes created by the dominant culture. Since the basic Marx Brothers act depends on audience awareness that they are already overdoing existing stereotypes, then perhaps this sequence of The Big Store is offered as a subversive satire of common stereotypes. If that is the case, then the Marx Brothers are functioning as allies by pointing to a commonality among non-dominant groups. One year earlier, the film Go West (1940) also offered Indigenous stereotypes, but then it went to greater lengths to ridicule them. Chico blows into a buffalo horn that is part of a headdress and the resulting sound sets up a rapid transformation into a Scottish stereotype. At another point, Groucho pointedly asks, “Who put your head on a nickel and then took the nickel away?” (See figure 7.16.)

In hindsight, there is often a fine line between being an ally and being in bad taste. Sometimes, both things happen at once. The mere appearance of a stereotype is likely to offend those who understand its negative history. As a result, audiences today often struggle when confronted by older voice appropriations that were originally daring and subversive. However, it seems wrong to say that racial and ethnic stereotypes should never be used. Clearly, the Marx Brothers frequently used stereotypes to stage social criticisms of the dominant culture. Many 21st century comedians employ the same tactic. (Sarah Silverman, Chris Rock, and Eddie Izzard are prominent examples.) It is therefore important to examine the specific context of use before making a judgment about how a stereotype has been deployed. It is difficult to challenge stereotypes if art and popular art are not allowed to confront them directly.

With this in mind, let us backtrack and reconsider an earlier example. The animated film Dumbo was listed in Section 2 above with some other Disney films. The crows in Dumbo are undeniably offered as Black characters. But are they actually racist stereotypes as they function in the film? Alex Wainer proposes that “Dumbo’s crows subvert the common image of blacks at that period in Hollywood film history“ — they are portrayed sympathetically: “self-assured, free-wheeling, fully realized animated characters” (Wainer 1993, p. 56). It is crucial to note that the crows are the real heroes of this story. They, rather than Dumbo’s best friend, Timothy Q. Mouse, come up with the supportive strategy that gives Dumbo the courage to use his ears to fly. Although the crow scene has overlap with minstrel shows, Wainer points out that “[T]he crows as caricatures of lower class blacks immediately imply [their] marginality to mainstream society,“ providing motivation to support another character that society has cast aside as worthless.

The most troubling racial stereotype in Dumbo is not the crows but rather the Black circus workers who sing “The Song of the Roustabout” as they work with the elephants to set up the tents in the night when the circus arrives in a new town. (See figure 7.17.)

Here, the film engages in voice appropriation by putting words into the mouths of the workers. The song’s lyrics promote the worst of racial stereotypes: “African-American laborers sing about their contentment at their position in society,” bringing the show to Southern White children (Sellick 2018, p. 164). Here is a small sample of the song lyrics:

We never learned to read or write …

When other folks have gone to bed

We slave until we’re almost dead

We’re happy-hearted roustabouts …

We don’t know when we get our pay

And when we do, we throw our pay away.

In contrast, the friendship established in the crow scene highlights the mutual recognition of two sets of outcasts. The misfit elephant who is ridiculed and tormented gains the sympathy and support of the crows, who represent a group mistreated no matter how well they perform.

It is also significant that the other elephants reject Dumbo as a “disgrace” to their “race.” Dumbo is not simply an unfortunate individual. Like the crows, he is racialized. Therefore, there is more to their interaction than a positive portrayal of Black characters. Rather than merely accepting their ongoing mistreatment, the crows reach out to Dumbo, implying that the real solution is for America’s non-dominant groups to join forces and work together. The Dumbo-crow interplay “underscore[s] the need for cross-race mentoring” (Glassmeyer 2013, p. 108).

Russell Reising proposes another subversion element to this part of Dumbo. Because Dumbo’s success in flying depends on the crows, “Dumbo’s successful flight represents a recurring theme in African American history; that is, that in order to deal with … racial oppression, African Americans have repeatedly been forced/inspired to excel physically in way that [get] them audience recognition … if not acceptance” (Reising 1997, p. 317). Escape from mistreatment through magical flight was, Reising explains, a standard folk legend of the Black community that traced back to African culture. This reading is plausible and, if correct, it is another voice appropriation that subverts the film’s earlier acceptance of Jim Crow racism.

There is room to argue about how to interpret the humorous use of specific stereotypes in the Marx Brothers and Dumbo. However, they illustrate that stereotypes can be twisted to suggest messages supporting non-dominant groups. By working against familiar racial expectations, voice appropriation can be used in a subversive way.

7.9 Silencing and Country Music

A third, more recent example of allyship through voice appropriation deserves attention. However, it is not clear how much of its audience appreciated the subversion present in its voice appropriation.

In July of 2023, Tracy Chapman had a hit country song. She became the first Black woman to have the sole writing credit on a song that reached number one in airplay and streaming in the category of American country music. Her song “Fast Car” also reached the number two position for all music. However, Chapman was not the performer. The hit record was by White country singer Luke Combs. To put Chapman’s song in perspective, only four other Black women have had a writing credit on a number one country song. Those four were co-writers, not the sole writers (Bernstein 2023).

Combs hit the top of the charts with a cover version of the song. Chapman had a hit record with it in 1988, when it was generally described as folk music. Her earlier version reached number one in Ireland and Canada and number six in the United States, and it received a Grammy award in the category best female pop performance.

Clearly, there is content appropriation when a White male country singer performs a song written and popularized by a Black woman. There was some criticism of Combs for doing this, but much of that went away when Chapman released a public statement thanking him for the “honor” of giving her a number one country hit (Newman 2023).

Generally overlooked in the initial response to Combs’ content appropriation was an important detail. It was not just content appropriation. It was voice appropriation. Why this is, and why it counts as a significant act of being an ally, demands some background history.

If such things can be dated, there is agreement that country music as we know it was born on August 1, 1927, in Bristol, Tennessee. Pursuing the promise of cash money to sing “hillbilly” music for the Victor Talking Machine Company, a young woman from the Appalachian Mountains of Virginia sang “Bury Me under the Weeping Willow.” She was Sara Carter. Her 18-year-old cousin, Maybelle Carter, accompanied her on guitar and vocal harmonies. Sara’s husband, A.P. Carter, added limited harmony and claimed to be the songwriter. Collectively, they were known as the Carter Family. (See figure 7.18.) In a short time, they were major music stars and for several years their records sales may have been as much as 3% of the U.S. record industry. To put this number in perspective, their level of popularity comes close to Taylor Swift, who captured 4% of vinyl records sold in 2022-23. They are perhaps best known for the song “Will the Circle Be Unbroken.”

Three days after the Carter Family recording session in Bristol, another discovery was made. Jimmie Rodgers was singing at a nearby mountain summer resort and he also auditioned and was recorded. However, the record company wanted songs that were not under copyright, and they advised Rodgers that future recording sessions depended on his use of original or public domain material. Four months later, Rogers recorded “Blue Yodel.” It sold a million copies during the next few years, but then his career was cut short by his early death from tuberculosis. Although Rodgers was more successful than the Carter family during his career, his early death meant that he contributed fewer “standards” to the country music tradition.

Due to the discovery of both Rodgers and the Carter Family, the so-called Bristol sessions have been described as “the big bang” of country music. (See figure 7.19.) That is, it is the point of origin. Together, the two acts demonstrated that “hillbilly” music could be a highly profitable commercial music. The record industry rushed to record and promote White southern musicians. In addition, Maybelle Carter’s special significance should not be overlooked. Only 18 at the time, she was the first musician to be recorded using a guitar technique known as the Carter scratch. She is responsible for making the guitar one of the core instruments of country music. Although “invention” is hard to prove, she later explained that she invented the Carter scratch by adapting banjo-picking principles to the guitar (Doman 2005, p. 70). Between them, Rodgers and the Carter cousins generated the blueprint of the genre that developed into modern country music. As a result, Bristol is now the home of the Birthplace of Country Music Museum, a Smithsonian (U.S. government) affiliate.

The Bristol sessions were notable for another reason. Ralph Peer, the producer of the recording session, devised a plan to maximize profits from the new talent. Normally, songwriters receive a share of profits for broadcasts, performances, and recordings of their songs. At the Bristol sessions, Peer told the musicians that he wanted original material. Then he became the music publisher of their songs for a small cash payment that was included in the recording fee. He continued this practice for anyone who wanted to continue to work with him — and Victor — going forward. This gave an immediate payout to the performer. However, if the record became a hit, Peer kept the majority of the songwriting royalties. One rough estimate is that this method deprived Jimmie Rodgers of the equivalent of a million dollars in today’s dollars, and deprived the Carter Family of a substantial amount. However, they fared better than most performers, especially Black singers. For several decades, most of the industry failed to pay both country and blues songwriters their legally established royalties.

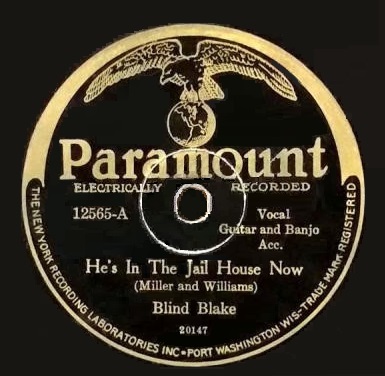

Given Peer’s demand for original material, how did the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers suddenly become expert songwriters of new material? They did it through content appropriation. For example, in 1928 Rodgers recorded the hit song, “In the Jailhouse Now.” Although Rodgers claimed to have written it, several musicians had already recorded it. Rodgers may have learned and then rewritten the version that was recorded and released by Blind Blake (Arthur Blake) a few months before Rodgers recorded it. (See figure 7.20.) Blake credited the song to two Black musicians, Al Miller and Jay Mayo Williams.

Early country music was saturated with content and style appropriation of this sort. The success of Jimmie Rodgers is merely one example in a long history of musical copying. Far from being distinctively “hillbilly” (that is, Appalachian), much of the music recorded in the first wave of country music was assembled from a mixture of sources. Rodgers’ singing style was directly influenced by the singing of Black railway workers that he heard during his earlier years as a railroad employee.