3 The Old World and the New: First Phases of Encounter, 1492-1617

Theodore Gracyk

Authorship

Sections 3.1 through 3.4 of this chapter have been edited, remixed, and extensively rewritten and expanded by Theodore Gracyk, based on Chapter 2 of American Encounters: art, history, and cultural identity, which is authored, remixed, and/or curated by Angela L Miller, Janet Catherine Berlo, Bryan J Wolf, and Jennifer L Roberts, and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/. Sections 3.5 and 3.6 are the original work of Theodore Gracyk.

Chapter Goals

- Understand that images are cultural products

- Understand that art reflects and promotes cultural assumptions

- Recognize appropriation in early images of Indigenous peoples

- Understand how myths influenced early images of Indigenous peoples

- Identify racial assumptions made by Europeans

- Explore multiple artworks featuring Matoaka (Pocahontas)

As you read this chapter, keep in mind that it covers a time period before the modern concept of race was developed and applied to intercultural relationships. The modern concept of race entered general use only in the later part of the 18th century (see Chapter 2, Section 2.2). Therefore, except for two examples at the end of the chapter, the material in this chapter discusses the development of various stereotypes, but they were not yet racial stereotypes. Their adoption as racial stereotypes came later.

3.1. The Earliest Images

It is common to think that good artists can simply look at a thing and make an accurate image of what they want to show their audience. However, the images that artists produce reflect their training. With the possible exception of the earliest cave and rock art of our ancient ancestors, every work of art is influenced by some earlier art. Like everyone else, artists are enculturated.

As distinct cultures developed in different places, regional differences emerged. European drawings of the year 1500 look very different from those produced around the same time within the borders of present-day China or India. And the differences are not simply a matter of style. What gets shown is very different, too, based on what is considered most important. Images generally reflect a familiar narrative, story, or theme that will make the contents accessible to the intended audience. For example, pictures of landscapes are very rare in European art before the 16th century, but they were common in Chinese art. This difference reflects cultural differences about our relationship to nature. Generally, Europeans regarded nature as something to conquer and transform. In contrast, Chinese Confucian thought treated nature as a model of cosmic harmony.

So, when Europeans first arrived in the Americas, artists who produced pictures to show the so-called “New World” to Europeans did not operate as neutral reporters. They based their images on existing European values, myths, and art. In other words, all of our early images of the Americas are filtered through the lens of European cultural expectations and artistic rules.

Furthermore, the artists were often illustrating written accounts of things that others had seen, so the images are full of imaginative recreation. As a result, the earliest images of first encounter tend to disclose as much about European wishes and desires as they do about observed realities. Some time needed to elapse before those who voyaged to America were able to see its Indigenous peoples — so radically different from themselves — with any degree of objectivity.

To put this point another way, European artists presented the Indigenous peoples of the Americas in terms of basic beliefs, art, and myths of European cultures. In doing so, European artists generally presented them as strange, “other,” and exotic. (See also Chapter 6, Section 6.2.)

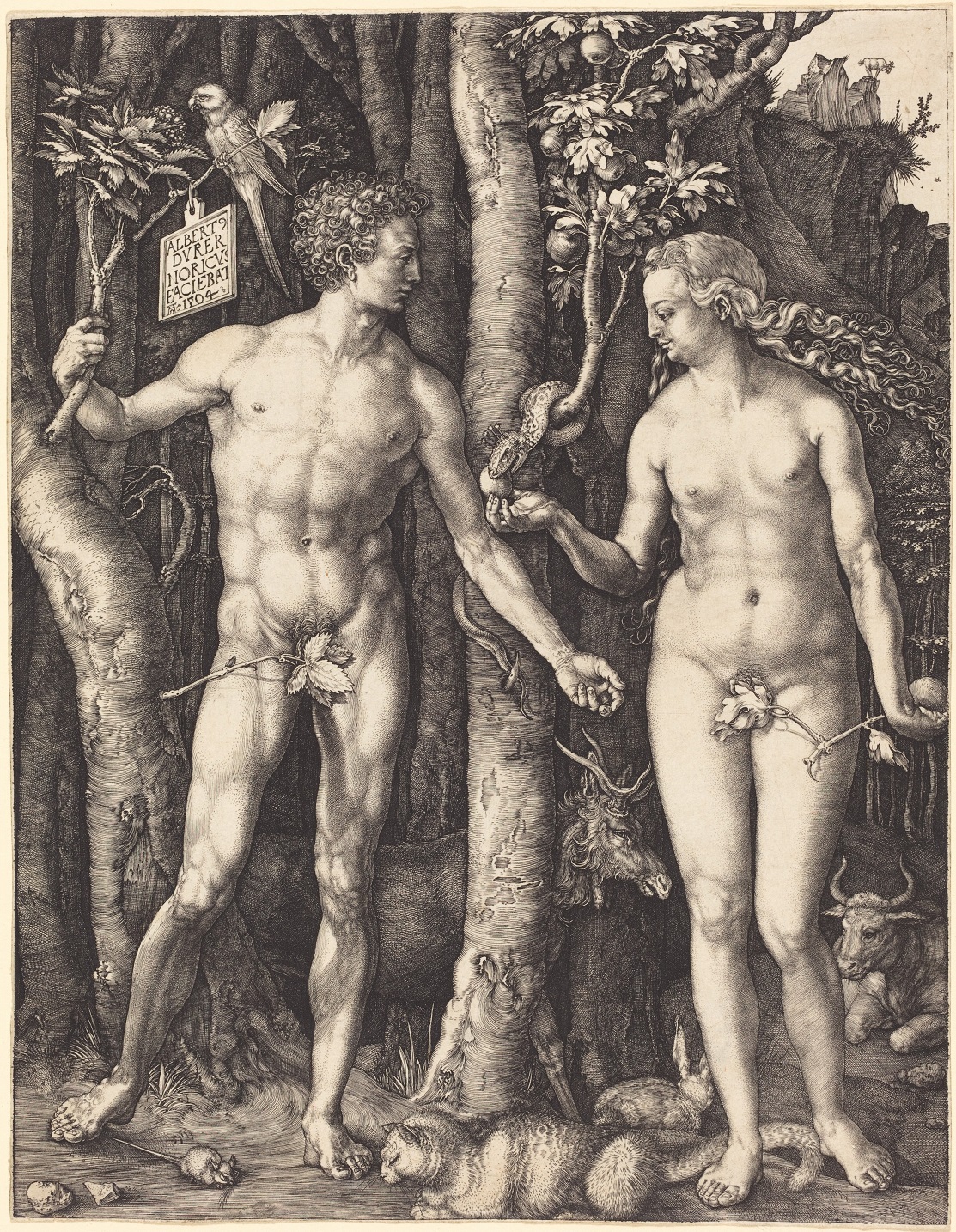

The first images of the indigenous peoples of the Americas generally focused on their nakedness. (See figure 3.1) In Europe, Judeo-Christian culture associated nakedness with the innocence of Adam and Eve before their expulsion from the Garden of Eden. (Once Adam and Eve realized they had sinned, they were no longer innocent and they put on clothing.) At the same time, simple nakedness was opposed to nudity. Italian Renaissance art had revived the ancient practice of creating positive images of the human body as a naturally beautiful thing. This celebration of nudity was a revival of ancient Greek and Roman values. Instead of being something shameful, the nude body displays and celebrates young, athletic, fit bodies as a way of expressing human perfection. With the exception of Adam and Eve before they sinned, traditional Christian culture normally displayed naked bodies to convey human vulnerability. In the traditional Christian context, exposed bodies were not so much beautiful as imperfect. A lack of clothing communicated a lack of defining traditions, rites, and religion. In summary, Europeans arrived in the Americas at the height of the Renaissance, and their art contained two traditions of unclothed people: the naked, and the nude.

Given this context, most early images of the nakedness of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas communicated that they were not “civilized” peoples. And they were generally shown in settings that suggested the land was undeveloped, suggesting that the land was available for European settlement.

This is not to say that the Indigenous peoples of the Americas actually lacked culture, laws, and ideas about territorial rights. It is to make a point about how Europeans emphasized and even exaggerated their lack of clothing as evidence that these people did not have their own distinctive culture. And it is important to stress here that we are not guessing at the meanings that Europeans associated with these kinds of images. Even after hundreds of years of interaction between Europe and the Americas, Europeans continued to believe that the Indigenous peoples of the Americas lived in a pre-civilized condition. For example, Adam Ferguson gives a clear statement of the 18th-century view that the lifestyle of Indigenous Americans proved that all humans originally lived as savage barbarians: “the present natives of North America [are just like the British people] at the time of the first Roman invasions, … ignorant of agriculture … [and so] the naked savage … in the customs of barbarous nations … is in their present condition [a mirror image of] own progenitors” (Ferguson 1767). (Readers should take note that at this time the word “savage” meant wild or untamed, and indicated a lack of civilization or culture.)

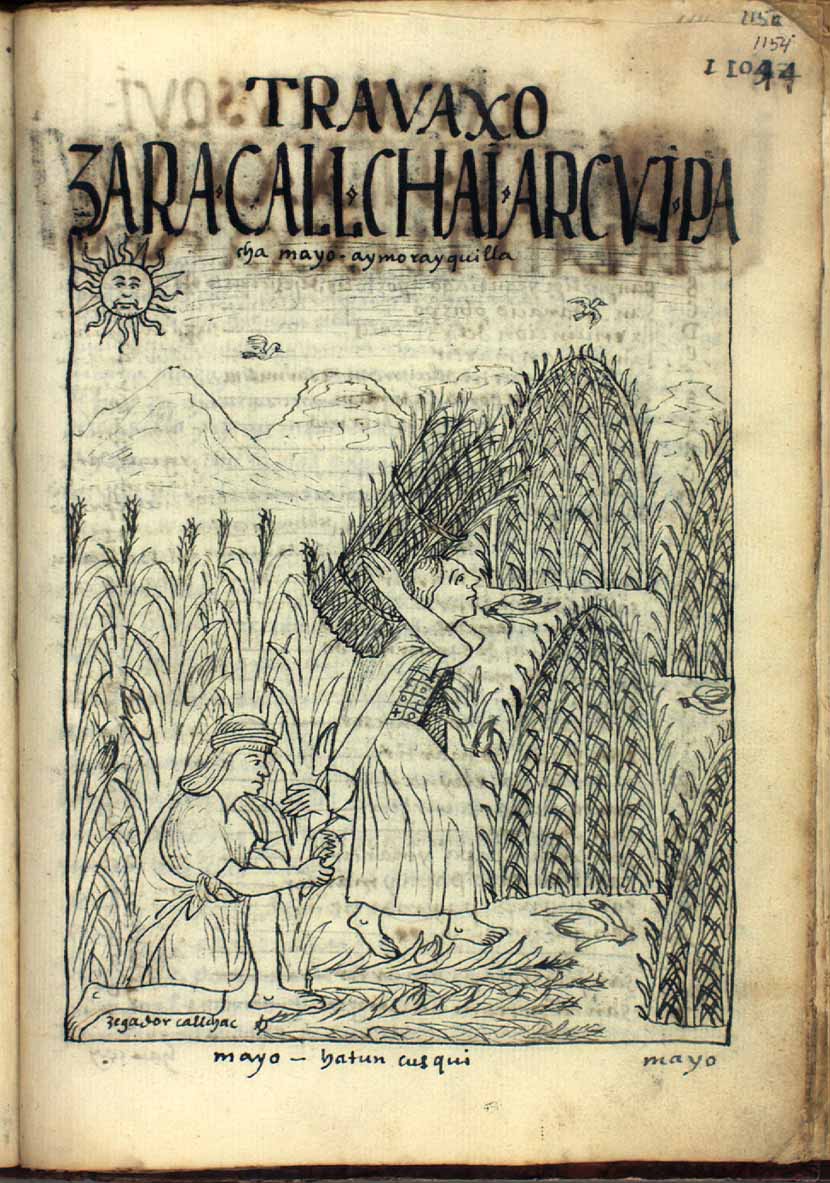

As a matter of historical fact, “civilization” arose in seven distinct places that independently developed the domestication and farming of grain crops. Three of these sites are in the Americas, spread among North, Central, and South America. Spanish explorers and colonizers encountered the cultivation of corn and potatoes, and pictures of Indigenous farming practices are recorded in Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala’s The First New Chronicle and Good Government, a book about the complex society of the Inca Empire. The book includes de Ayala’s multiple sketches of the planting, tending, and harvesting of crops. (See figure 3.2.) However, by then it was too late: the myth that the Indigenous peoples of the Americas were “ignorant of agriculture” and simply lived off the land was already firmly established in the minds of many Europeans.

3.2. Paradise and Hell

At the time of first contact between Europeans and the Americas, educated Europeans were conditioned to believe that civilization flowed from the dual sources of Judeo-Christian religion and Greek and Roman culture. As a result, they “knew” that the newly discovered lands lacked civilization. How could there be civilization in a place untouched by Christianity and Classical education, laws, and social organization? As a result of these biases, Europeans imagined the Americas as both paradise and hell.

This dual perspective is strikingly apparent in a woodcut published in 1505 in Augsburg, Germany (look again at figure 3.1). The image was accompanied by lines from Amerigo Vespucci that instruct us how to think about the picture: “The people are … naked, handsome, brown, well-formed in body [and] covered with feathers …. No one owns anything but all things are in common. The men have as wives those that please them, be they mothers, sisters or friends. … They also fight with each other. They also eat each other even those who are slain, and hang the flesh of them in smoke. They live one hundred and fifty years. And have no government.”

The gruesome remains of unfortunate explorers hang from a tree. In the foreground cannibals gnaw upon severed body parts. In the distant background are two Portuguese ships. (We know the ships are Portuguese because the image is illustrating Indigenous people of present-day Brazil.) Yet in the same print are blissful scenes of love beneath a wooden bower, nursing mothers and children, and stately men in feathered skirts and headdresses. The ideal of a paradise to the west, beyond the pillars of Hercules (Gibraltar), lived on from Classical antiquity, shaping attitudes toward the Americas. But coexisting with this was a fascination with what Europeans perceived as monstrous, uncivilized behavior — nakedness, free love, cannibalism, and other practices threatening European notions of civilized life. This duality would persist through the next four centuries of European encounters with the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Heaven for the Indigenous people is hell for the Portuguese.

This image is also the earliest that shows Indigenous Americans with feathered headdresses. Europeans saw examples of such headdresses and these grass skirts when they first encountered the Tupinamba people of present-day Brazil. Other Europeans later encountered similar headdresses among tribes in present day New York state and adjoining land in southern Canada. Because artists frequently engage in content appropriation, new pictures are frequently based on earlier pictures. Through a chain of content appropriation, the feathered headdresses of the Tupinamba people became a common feature in many illustrations of Indigenous Americans even when they were not appropriate. It quickly became a symbol that instantly communicated “Indian” to European audiences, so it was often used even if it was not accurate for the particular tribe that was shown.

3.3. A Beckoning Princess

For Europeans, the strangeness of the Americas made it easy to imagine it as a “bower’d” arcadia. In Greek mythology, Arcadia is the earthly forest home of the god Pan, who was the god of shepherds, hunters, and woodlands. The ideal of an unspoiled place without work or struggle was frequently contrasted with the pressures and competition of city life. Centuries later, Roman mythology appropriated the idea of Arcadia, and it was celebrated anew by the Roman poet Virgil as an ideal place of peace, prosperity, and love. The ten poems of Virgil’s Eclogues became highly popular as printed books spread during the Renaissance. Richard Jenkyns says that Virgil’s poems are likely “the most influential group of short poems ever written” (Jenkyns 1989, pp. 26-27). The poems inspired several other very popular Renaissance books, including Jacopo Sannazaro’s Arcadia (1504) and Sir Philip Sidney’s The Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia (1593). Therefore, the myth of Arcadia was popular during the same period that Columbus first sailed and Spanish and other colonizers followed him to the Americas. Due to their early impression that the Americas lacked cities and large-scale agriculture, it was easy for Europeans to make the connection between the Americas and this arcadian mythology. This association influenced both descriptions and images.

In the narrative of the Americas as a newly discovered arcadia, Indigenous peoples were assumed to be hunter-gatherers. Food was so abundant that no work was required to pluck the fruits of the earth, and there was no private property, so “mine” and “yours” were unfamiliar concepts. The possibility of moving to this bountiful “New World” delighted a Europe racked by prolonged wars and political and religious turmoil. Europeans marveled at a new people apparently without guile, selfishness, or inhumanity and who appeared to be free of legal disputes, weights and measures, money, and books. Living in harmony with nature, they knew noting of lying, deceit, joyless labor, greed, envy, jealousy, and dishonesty. Early descriptions associate the peoples of North America with a life of liberty and unfettered pleasure, living in a moral innocence. In short, Europeans thought of them as having the status of Adam and Eve before “the fall.”

Trends in Renaissance art encouraged Europeans to make all of these connections. The first European images of America’s Indigenous peoples appeared shortly after nudity had become more common in European art. (This new tolerance for images of nudity was a cultural appropriation from Greek and Roman antiquity.) While some early images treated Indigenous peoples as shamefully naked, other images soon took their place, replacing nakedness with nudity.

Among Europeans, the story of Adam and Eve was a common subject in visual art, and this Judeo-Christian origin story was a powerful model for thinking about Indigenous peoples. The German artist and printer Albrecht Dürer frequently made prints of Bible stories, and these prints were seen throughout Europe. In 1504, he designed an influential image of Adam and Eve just before they eat the forbidden fruit and commit the first sin. (See figure 3.3.) As previously explained in Chapter 1, the image is based on substantial content appropriation from the pre-Christian Classical world.

Dürer strategically places tree branches so their nakedness is partially covered. This detail looks ahead to the next stage of the story. Ashamed of themselves after they eat the fruit, they will try to cover up their naked bodies with these same branches and leaves. But at the moment they are pictured, they have not yet disobeyed God, and the world of nature is perfect and at peace. Notice, for example, the animals on ground level around the man and woman. A domesticated bull and a wild deer are equally comfortable with the human couple, and a rabbit and a mouse do not fear the nearby cat. Nothing threatens anything else. But after God punishes them for their disobedience, all of nature outside this “garden” will be transformed into a threatening wilderness. Nature will become (to quote the poet Alfred Lord Tennyson), “red in tooth and claw.” But notice that Dürer presents Adam and Eve as beautiful, unashamed nudes, rather than as naked people. They do not become naked until it occurs to them that they should cover themselves. To picture them as nudes, Dürer engages in cultural appropriation from ancient, Pagan statues of pre-Christian Greece and Rome. (For more details, see Chapter 1, Section 1.4). In the paradise of Eden before the fall into sin, Adam and Eve have no needs, do not have to work, never get older, and exist in a happy, pre-civilized existence.

Although it is visually very different, the symbolism that informs Dürer’s approach to Adam and Eve is appropriated and reworked in the print Allegory of America, one of a set of prints about the continents by Dutch artist Jan van der Straet. (See figure 3.4.) These prints were made nearly a century after the Spanish first arrived in the Americas. At this point, the “New World” had been named America in honor of Amerigo Vespucci, the navigator and explorer credited with popularizing the idea that South America was not part of Asia and the Indigenous people were not natives of India. This image shows Vespucci arriving in South America. He was part of an early Spanish expedition to that Continent, in 1501.

In the image, Vespucci approaches and awakens a native woman who has been sleeping in a hammock. Her war club is out of reach, leaning against the tree on the left. She is sexualized and vulnerable. In the bottom left corner, we see an anteater, native to Central and South America. Appropriating from a range of visual sources, the artist has combined details from Brazilian, Caribbean, and Mexican cultures into a single image. In the background, in the very center, women are sitting by a fire and they are roasting a human leg. In this way, the image reaffirms the earlier image (figure 3.1) of the Indigenous people as uncivilized cannibals. Vespucci’s flag staff is topped with a cross, symbolizing the arrival of Christianity. In his other hand he holds a navigation instrument, an astrolabe, indicating both his profession and, more generally, the advanced knowledge and technology of Europe. The crucial point of the image is that the woman who greets Vespucci symbolizes all of the Americas: she is America, personified. (“America” is the feminine of “Amerigo.”) Vespucci is presented as the civilizing power of Christian civilization, and America welcomes him. By implication, America welcomes Christianity and, with it, European culture with its laws and moral standards.

The allegory presents an exotic and feminized new world receptive to colonization, and this allegory would be appropriated by other artists for many generations to come.

The most important suggestion of the allegory is that it is not a meeting between equals. European culture of the time did not regard women as equal to men. With the arrival of Christianity, the woman’s nudity is transformed into nakedness, and the nearly naked woman is powerless, and, by implication, sexually available. She is not yet a person according to the standards of European culture, and the man can do with her as he wishes. Working out the implications of this allegory, the picture is endorsing the view that European men can do what they want with all of South, Central, and North America.

Keep in mind that visual art is not the only mode of art, and it is not the only art that features symbolism in which the “New World” is sexualized as an object for conquest. The same theme is found in the literature of this period, most famously in John Donne’s poem, “To His Mistress Going to Bed.” Written five or so years after van der Straet created his visual image of a naked America, Donne’s poem reads, in part,

Your gown going off, such beauteous state reveals …

O my America! my new-found-land, my kingdom …

Show thy self: cast all, yea, this white linen hence …

To teach thee, I am naked first.

It is notable that the poem does not communicate the woman’s response. The male point of view is the exclusive focus, and the man commands his “America” to strip herself and to make her body available to him. He will be to her what Europe is to America. The poem puts the European attitude on full display.

3.4. The “Noble Savages” of Virginia

These first encounters also gave us an image of the “noble savage,” the personification of multiple ancient European myths. The phrase itself was first used in 1609, by French writer Marc Lescarbot, but he was probably inspired by visual images that were already in wide circulation. One of the most interesting of these images was created in 1590 to illustrate a published account of early English exploration of the area of North America that the English claimed for themselves as the new domain of Virginia. (See figure 3.5.) This image originates in a drawing by John White, who had visited Roanoke Island, in present-day North Carolina, two hundred miles to the south of the Virginia settlement. So, the illustrations actually show a different tribe than the one described in the text. (Although both groups were part of the general Algonquian culture, the lack of attention to tribal differences is one of many cases that show a European tendency to treat all Indigenous peoples as more as less interchangeable.) Notably, the book, Thomas Harriot’s A Brief and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia (1590) opens with an image of Adam and Eve. By doing this, the book signals that Harriot’s account of newly discovered “savage nations” (i.e., uncivilized peoples) would reveal a pre-Christian garden of Eden.

The book’s image of the “great lord” or chief was placed beside Harriot’s description of Indigenous warriors, stressing that their diet was based on the plentiful deer and fish of the region. In this way, Indigenous people were once again portrayed as hunter-gatherers rather than people who engaged in the planting and harvesting of crops. (Notice that hunting is taking place in the background, with a deer fleeing on the right.) The man is shown holding an English long bow instead of an authentic Indigenous bow. This was done to make the man look more like an English soldier (Tucker 2008).

The muscular body and the basic stance of this figure are dictated by European art training of the time. They incorporate what artists of the time had learned by studying the nude statues of ancient Greece and Rome, or by studying contemporary art based on the older statues. During the Renaissance, artists generally learned to draw the human form by sketching statues instead of living persons, and as a result standardized motifs or design principles informed most pictures of the human form produced in this era. Both John White and the print-maker, Theodore de Bry, were trained in this way. This training is most apparent in the figure’s contrapposto stance, which anchors most of the body weight on one leg. (Look again at Figure 1.10 in Chapter 1, focusing on the legs and body stance of the Apollo statue that Dürer used as a model for Adam in his print, figure 3.3 above.). Although de Bry often made the figures in his versions more “classical” than in White’s drawings, in this case the contrapposto stance appears in White’s original drawing.

White may have appropriated the stance of “A great lord of Virginia” from a specific Renaissance statue. The statue is Donatello’s famous bronze statue of the Biblical character of David. Donatello’s statue was produced about fifty years before Columbus sailed, and David’s left arm, with hand on hip, is strikingly similar to what we see in A Great Lord of Virginia. (See figure 3.6.) Again, educated European audiences are invited to make a connection to the pre-Christian era, either through a common motif appropriation from antiquity or from a more specific reference to an Old Testament king in his role as defender of his people. Either way, the heroic figure created by White and appropriated by de Bry is associated with the ancient past, and so it conveys the message that the Indigenous people of Virginia are civilized, but not in the Christian manner of — and so not equal to — the English colonists who were sailing to their shores.

Appropriation of standard Renaissance designs appear in several of the book’s other illustrations, such as “Their dances which they use at their high feasts.” (See figure 3.7) The image is spread over two pages, and in the center there are three dancers who are grouped together, their arms draped over each other’s shoulders. The basic image or motif would be familiar to educated people from numerous Renaissance paintings and prints: this is a standard way of showing the three graces, the mythical Aglaia, Euphrosyne, and Thalia. In Greek myth, they were the handmaidens of Aphrodite, the goddess of love (and, in later Roman mythology, of Venus). The three graces were frequently portrayed in this arrangement because it allowed artists to display the human form, naked or lightly clothed, from three dimensions. Through their association with Aphrodite/Venus, they were more or less automatically sexualized. By inserting the familiar grouping of the graces into an Indigenous ceremony, the image reinforces their lack of Christian culture. Like the earlier image of Vespucci and the allegorical America, it also invites European viewers to interpret their nudity and near-nudity as a sexualized display.

The group of three is present in the original drawing by John White, but de Bry modified them to make them more slender and graceful. In fact, de Bry altered almost every figure in the illustration. To offer another example, de Bry gives the figure to the far left a toga to replace the animal skin of White’s original.

The lesson here is that early published portraits of Indigenous peoples are not neutral, objective pictures. They were presented to the public though a filter of material appropriated from European antiquity. In this way, they reinforced ideas that Europeans already had about “uncivilized” people. (Given how they thought about the past, “pre-civilized” is probably a more accurate term for their understanding of things.) A closely related point is that European Renaissance artists had worked out a visual vocabulary for communicating these standard ideas. These existing visual models were then appropriated and adapted to illustrate the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. In this way, they encouraged specific responses to the people who are pictured. Above all, the pictures are designed to confirm that the inhabitants of this newly-discovered Arcadia do not live according to rules that govern civilized Christians.

Just as Theodore de Bry had appropriated from John White, a whole generation of European artists copied and adapted the illustrations that de Bry made for A Brief and True Report. (See figure 3.11 below and accompanying discussion.) In this way, the basic visuals made their way into illustrations of many peoples in many parts of the Americas. Once it became established, the image of the “noble savage” persisted for centuries. It gained further support in the 18th century, in the writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and then in the cultural movement known as Romanticism. As explained in Chapter 5, these new intellectual developments appeared just after the United States became independent of England, reinforcing the stereotype that Indigenous peoples lack genuine culture and influencing U.S. artists and policy makers as the new country expanded westward.

3.5 Appropriating Pocahontas

The English colonization of present-day Virginia merits special attention, because it gave Europeans a story and visual image that confirmed their expectations that the spread of Christianity was the only way to “civilize” Indigenous peoples. The story and image are that of Pocahontas, a member of the Powhatan tribe who married Englishman John Rolfe and died around time she turned twenty-one, in 1617. But Pocahontas was not really her name. It was her childhood nickname (meaning something like “willful child” or “spoiled child’). Her own people speak of her with the names Matoaka and sometimes Amonute. After her marriage she was renamed Rebecca Rolfe.

It is important to say, up front, that we have good reason to think that the most dramatic and famous element of her story is a complete fiction (Lemay 2010).

The first image to examine is the only known likeness of Pocahontas made by someone who actually met her. (See figure 3.8.) A portrait was created when Pocahontas/Matoaka visited England with her husband and their son. (To put it in historical perspective, the Rolfe family probably boarded the ship to England the same week that William Shakespeare died.) The image was widely circulated in print and then in several painted copies.

What surprises most modern viewers is that when we take away the identifying caption, the picture could show any prosperous Englishwoman of the time. But, for the English, that was the core message of the painting. She had converted to Christianity while a hostage of the English settlement in Virginia, and subsequently married Rolfe, and these events had been widely reported in England as evidence that a “civilized” relationship between colonizers and colonized was possible. Rolfe brought her to England to display her in high society and to raise support (and further funding) for the colony. So, it was important to display her as a proper Englishwoman: she had been transformed by Christianity and was no longer the “Pocahontas” of the Powhatan tribe. This transformation was central to the publicity campaign of the London Company, the colony’s financial backer. She proved that the Indigenous peoples could be transformed. This meant that long-term conflict between colonizers and tribal peoples was not inevitable, boosting support for further colonization.

If we return to the earlier allegory of Vespucci and America (see above, figure 3.4) and set it beside the portrait of Rebecca Rolfe, we might think of them as “before” and “after” pictures. (Europeans who saw Rolfe’s portrait in the 17th century probably made a comparison of this kind in their imaginations.) The portrait of Rebecca Rolfe was visual evidence that a semi-nude Powhatan girl was transformed after she joined forces with the newly-arrived colonizers and embraced Christianity. (The word “baptized” is slightly larger than all the rest of the text in the label under the picture.) From the perspective of the English, she had become civilized by embracing Christianity.

Historically, therefore, the baptism and marriage were treated as the most important aspects of the life of Pocahontas/Matoaka. A huge painting, Baptism of Pocahontas, has been on display in the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol building since 1840. (See figure 3.9.) Hanging beside images of Columbus’s arrival and the signing of the Declaration of Independence, the image shows her fiancé, John Rolfe, standing a few feet behind her. Behind him are members of her family, several of them portrayed as disrespectful and unhappy about the conversion. Through its placement in the rotunda, the picture shows that 19th-century Americans gave this historical event the same importance that they assigned to the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Why? Her baptism represented the first step toward a general erasure of Indigenous religion and cultural identify.

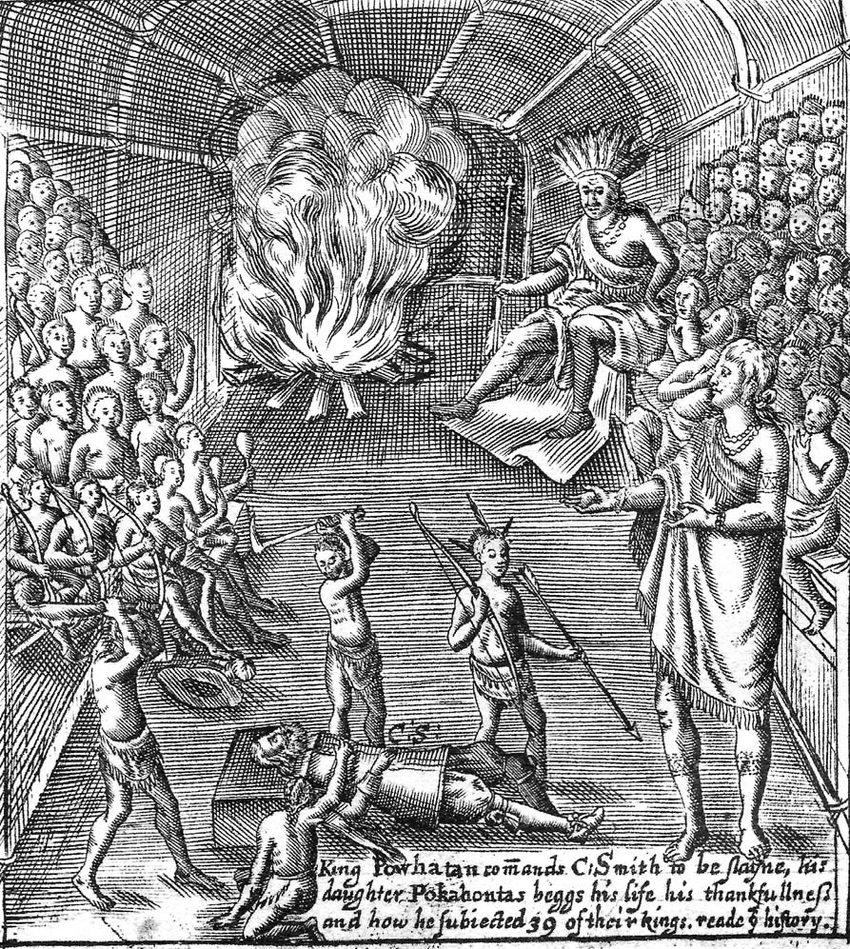

None of the above depends on knowing the famous story of Pocahontas saving the life of John Smith. (See figure 3.10.) That story was spread by Smith himself, but only after she arrived in England in 1616. It is worth taking some time to read Smith’s description of his early encounters with the Indigenous people of Virginia, and about his (alleged) first encounter with Pocahontas. For that purpose, here are two crucial paragraphs from Chapter 2 of his account of his time in Virginia. Smith writes about himself in the third person here. We begin with his account of his capture by “barbarian” warriors in “the desert” (in the wilderness). (Spellings have been modernized.)

Smith’s Account of His Capture by the Powhatan People

Smith little dreaming of that accident, being got to the marshes at the river’s head, twenty miles in the desert, had his two men slain (as is supposed) sleeping by the canoe, while himself by [hunting fowl] sought them victual [i.e., food], who finding he was beset with 200 savages, two of them he slew, still defending himself with the aid of a savage his guide, whom he bound to his arm with his garters, and used him as a [human shield], yet he was shot in his thigh a little, and had many arrows that stuck in his clothes but no great hurt, till at last they took him prisoner. … Six or seven weeks those barbarians kept him prisoner, many strange triumphs and conjurations they made of him, yet he so demeaned himself amongst them, as he not only diverted them from surprising the [English] Fort, but procured his own liberty, and got himself and his company such estimation amongst them, that those savages admired him more than their own Quiyouckosucks [gods]. The manner how they used and delivered him, is as follows.

… At last they brought him to Meronocomoco, where was Powhatan their emperor. Here more than two hundred of those grim [warriors] stood wondering at him, [as if] he had been a monster. … Before a fire upon a seat like a bed stead, [Powhatan] sat covered with a great robe, made of racoon skins, and all the tails hanging by. On either hand did sit a young wench of 16 to 18 years, and along on each side the house, two rows of men, and behind them as many women, with all their heads and shoulders painted red; many of their heads bedecked with the white down of birds … and a great chain of white beads about their necks. At his entrance before the king, all the people gave a great shout. The Queen of Appamatuck was appointed to bring him water to wash his hands, and another brought him a bunch of feathers, instead of a towel to dry them: having feasted him after their best barbarous manner they could, a long consultation was held, but the conclusion was, two great stones were brought before Powhatan: then as many as could laid hands on [Smith], dragged him to them, and thereon laid his head, and being ready with their clubs, to beat out his brains, Pocahontas the king’s dearest daughter, when no [pleading to spare his life] could prevail, got his head in her arms, and laid her own upon his to save him from death: whereat the emperor was contented [Smith] should live to make him hatchets; … for they thought him as [capable] of all occupations as themselves. For the king himself will make his own robes, shoes, bows, arrows, pots [and could] plant, hunt, or do anything so well as the rest.

Smith is writing about events that took place in 1607. However, we have good reason to think that Smith’s account of meeting Matoaka (Pocahontas) is fictional. The oral history of the Mattaponi tribe says that Smith and the pre-adolescent girl could not have met in this way (Custalow 2007). Children were strictly forbidden from attending a ceremony of the kind Smith describes. (She was around eleven years old in 1607.) Oral tradition also says that the event was an initiation ceremony to welcome Smith, rather than an execution. There is no record of Smith writing down or communicating this story about his first meeting with Pocahontas until 1616. By then, she was already relatively famous in England because of her 1614 marriage to John Rolfe. In addition to the marriage, her conversion to Christianity was being publicized to support settlement of Virginia. It is likely, therefore, that Smith is associating himself with someone who is already popular and famous and he is slanting the truth to make a personal connection with her. In his version, his contact with her predates that of other English colonizers. Smith engages in a type of content appropriation, changing the story to fit himself into it.

Because Smith’s tale about their first meeting is a literary fiction, we should ask why he made up the story. What is its intended symbolic value or impact? The answer offers a clue about its enduring popularity. Basically, the story singles out one individual in the Mattaponi tribe as different from everyone else. In Smith’s story, the evil “savages” are going to kill him. She alone violates tribal custom, which positions her as a “good” and “friendly” girl who alone endorses the Englishman, Smith. By extension, she gives her approval to colonization prior to her baptism. Her alignment with Smith involves her rejection of tribal custom. So, Smith’s story implies that she is already disposed to accept the morality of Christianity (e.g., “love thy enemy”). In this way, her intervention sets the stage for her later conversion to Christianity. In other words, goodness is associated with the replacement of Indigenous custom and values with European Christian culture.

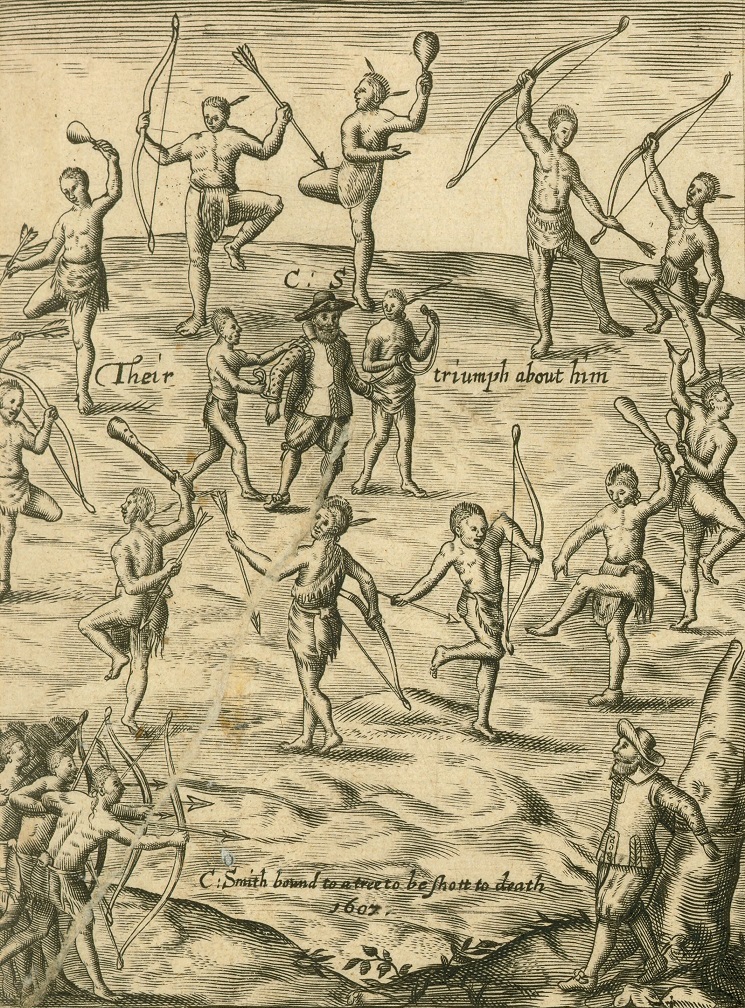

Other illustrations printed in Smith’s book reinforced this message. Many of these illustrations involve significant content appropriation from the earlier pictures that Theodore de Bry derived from the drawings of John White. In the material reproduced above from Smith’s book, the first paragraph is an account of his capture by the Powhatan warriors. This event received its own illustration. (See figure 3.11, where Smith appears twice in the image, in both center and bottom right.) A comparison with de Bry’s illustration of an Indigenous dance ceremony (figure 3.7) shows the extent of the content appropriation. However, the image has been systematically altered to create violent, threatening warriors. This picture is one of many similar appropriations in Smith’s book, all meant to make him look heroic and, at the same time, to demonstrate the extreme savagery and violence of the Algonquian-speaking people (Winchcombe 2022). The clear message was that colonial settlers could not possibly live in harmony with them and the land must be taken by force. Along with Smith’s narrative, these altered images promote a view of Pocahontas/Matoaka as a unique and special case, rather than a demonstration of the potential for the English and the Powhatan to live in harmony in a shared Christian society.

The famous rescue story has remained popular for four hundred years and was frequently repeated in art and literature. For example, here is a popular 19th-century poem that rewrites it so that it sounds like a battle among medieval European knights. Many 19th-century readers would have understood that this poem associates Smith with the English Crusaders who “freed” the Holy Land. The opening verse continues the tradition of portraying colonial settlers as Christian, noble, and heroic, and so justifying their violence. Notice, also, that the original detail of clubs aimed at Smith’s head is replaced by burning at the stake. The last verse introduces voice appropriation by claiming (falsely) that the oral tradition of the Mattaponi tribe confirms the rescue story.

Pocahontas

William Makepeace Thackeray, 1848

Wearied arm and broken sword

Wage in vain the desperate fight:

Round him press the countless horde,

He is but a single knight.

Hark! a cry of triumph shrill

Through the wilderness resounds,

As, with twenty bleeding wounds,

Sinks the warrior, fighting still.

Now they heap the fatal pyre,

And the torch of death they light:

Ah! ’tis hard to die of fire!

Who will shield the captive knight?

Round the stake with fiendish cry

Wheel and dance the savage crowd,

Cold the victim’s mien and proud,

And his breast is bared to die.

Who will shield the fearless heart?

Who avert the murderous blade?

From the throng, with sudden start,

See, there springs an Indian maid.

Quick she stands before the knight,

“Loose the chain, unbind the ring,

I am daughter of the king,

And I claim the Indian right!”

Dauntlessly aside she flings

Lifted axe and thirsty knife;

Fondly to his heart she clings,

And her bosom guards his life!

In the woods of Powhattan,

Still ’tis told, by Indian fires,

How a daughter of their sires

Saved the captive Englishman.

3.6 Reverberations

The Massachusetts Bay Colony was created a few years after Rebecca Rolfe’s visit to England. This new colonial venture gave us another potent myth, that of the first Thanksgiving. But even before the Puritan “pilgrims” sailed for North America, they had created their own government seal for official documents. The seal was reproduced and circulated by the U.S. postal service to commemorate three hundred years from their arrival in Massachusetts. (See figure 3.12. For further discussion, see Chapter 1, Section 1.6.) The design itself dates from 1629, and it pulls together many of the founding myths about the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. It makes explicit what is implied by the Rolfe portrait. A naked (and therefore uncivilized) man throws out his arms in welcome, holding his arrow away from his bow to show he is not hostile, and from his mouth emerge the words “Come over and help us.” He is portrayed as calling across the ocean and inviting colonization to “help” him with Christianity and European governance. This image, like the nude “Columbia” greeting Vespucci, expresses the colonizer’s view that their religion and way of life were superior and should be welcomed by the Indigenous people they displaced and oppressed. In this way, we see that the voice appropriation of the seal of the Massachusetts Bay Colony builds on earlier voice appropriations.

The myths supported by the earliest art of first encounters were endlessly re-used as the United States expanded across the continent to the Pacific Ocean. More than two hundred years after the creation of the Pocahontas myth, we find them recycled yet again in Erastus Dow Palmer’s Indian Girl, or The Dawn of Christianity (mid-1850s). (See figure 3.13.) As was the case with earlier images, her naked torso symbolizes a “natural” or uncivilized life. It also communicates that she does not understand that it is shameful to expose her body. However, she holds a Christian cross and gazes at it, indicating that this is the moment of her conversion to Christian life and morals. Like Pocahontas, she will now abandon her upbringing and will assimilate, and her shameful nakedness will be covered up. In this way, Palmer appropriates the basic image and symbolism of Vespucci meeting “America” (see figure 3.4, above). At the same time, the assumption that Christianity will bring genuine morality is the artistic justification for sexualizing the Indigenous girl, communicating the message that Indigenous women are sexually desirable objects for male conquest.